Category:Military History

A category for all things military on the wiki. If you are looking for specific history on WW1 and WW2 in Chester, we are sorry if you are disappointed: those are specialist subjects on which a lot of very focussed people have written extensively. There may be some links on this site to better sources of information, but unfortunately we have not the time to give the subject the attention it deserves.

The city of Chester, from its essentially Roman foundation at a strategic crossing point on the River Dee has a strong thread of military history stretching from Roman Chester through the Dark Ages, the Viking period and the Civil War. Close to the border with Wales it has, as befits a border town, one of the best-preserved City Walls in the country, despite them having been fought over on several occasions. The border has fluctuated between the River Gowy, the River Dee and possibly even the nearby mid Cheshire Sandstone Ridge along which even a short walk along will touch on many interesting sites, from hill-forts to a nuclear bunker. The City of Chester and the surrounding country contain much to interest those concerned with military history. Simply to organise the material, this broken up into the sections provided below: the pre-Roman period of hill-forts, the Roman period, the early-modern (known also as the Dark Ages, the age of castles, the influence of gunpowder and the coming of mechanised warfare.

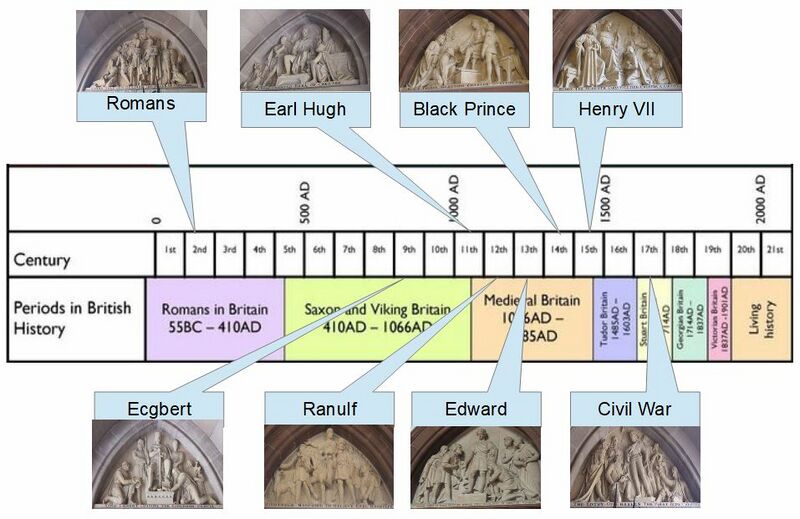

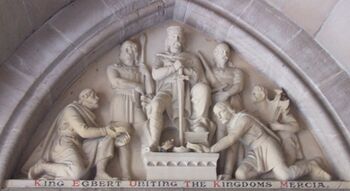

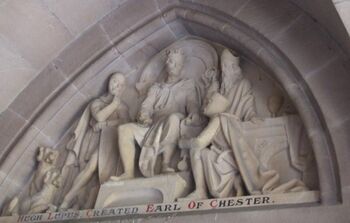

The Town Hall at Chester features a series of sculptures which illustrate the history of the city and they all, perhaps by chance, have some association with the military history of Chester.

Braumoeller (2019) stated:

- "However idiosyncratic the casus belli may seem, however, there generally is one ... The issues that prompt most wars fit fairly well into one of a fairly manageable number of categories."

He broadly summarised classical issues as territory, the creation or dissolution of countries, the defence of the integrity of countries, dynastic succession, and the defence of co-religionists or co-nationals. He also pointed out that in the modern field of peace and conflict studies, scholars frequently list causes such as:

- "struggle for power, arms races and conflict spirals, ethnicity and nationalism, domestic political regime type and leadership change, economic interdependence and trade, territory, climate change-induced scarcity, and so on"

Whatever the causes of war Chester has seen quite a bit of it.

Military History - Summary

The Romans left around 400 CE with their fortress having been the base for Legio II and Legio XX. During the Dark Ages which followed, the Battle of Chester took place in 616. The city was re-fortifed by the Saxons under Æthelflæd in the early 10th Century, her brother Edward the Elder died at Farndon after fighting at Chester and the Battle of Brunanburh was probably fought just north of the city. During the 11th Century it became the home to powerful Saxon earls. Equally powerful Norman Earls of Chester replaced these after 1066, when Chester was the last city to fall to the Normans, who promptly added Chester Castle to the defenses of the city as one of a string of Cheshire Castles along the River Dee. Local legend has it that Harold II survived the Battle of Hastings to live out the remainder of his life at the Hermitage.

During the time of Edward I Chester was an important base for the conquest of Wales. Later it was a much-favored city of Richard II (who was eventually imprisoned in Chester - leaving legends of his Royal Treasure being hidden nearby) and a source of revolt for his successors. Once a major port, Chester declined but was still important during the Civil War when a protracted siege and a further major battle took place. Chester resident Roger Whitley (1618 – 17 July 1697) was a royalist officer in the English Civil War, attaining the rank of Major General (2nd in command of their forces in the battle for the Isle of Anglesey) and was closely involved throughout the 1650s in plans for a royalist uprising against the Interregnum and Protectorate regimes. He had accompanied the young King Charles II into exile and carried the kings orders into Cheshire on the rising of forces, known as The Booth Rising, at the eve of the Restoration.

One often overlooked item of military history in Chester is the grave of Thomas Gould, who is buried under the roundabout between Grosvenor Street and Grosvenor Road. This is the site of the graveyard of St Bridget (since demolished). The grave marker is shaped as a casket and inscribed:

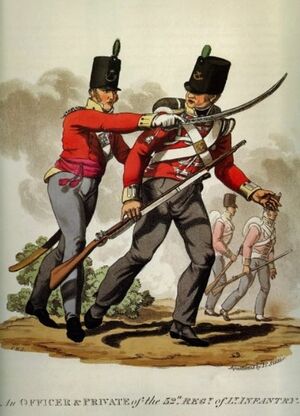

- IN MEMORY OF THOMAS GOULD LATE OF THE 52ND REGT. OF FOOT LI. DIED IN NOVEMBER 1865 AGED 72 YEARS 46 OF WHICH WERE SPENT IN THE SERVICE OF HIS COUNTRY. HE WAS PRESENT IN THE FOLLOWING ENGAGEMENTS. VIMERA, CORUNA, CROSSING THE GOE NEAR ALMEIDA, BSACO, PUMBAL, REDINHA, CONDEIXA, FOZ D'AVOCA, SARUGAL, FUENTES DONOLE, STORMING OF CUIDAD RODRIGO AND RADASOS SALMANCA, SAN MUNOS (fallen prisoner), ST MILAN, VITTORIA, PYRENEES, STORMING OF THE FRENCH ESTABLISHMENT OF VERA (wounded), NIVELLE, PASSAGE OF THE NEVE ORTHES, TARBES, TOULOUSE AND WATERLOO. HE RECEIVED THE PENINSULA MEDAL WITH 13 CLASPS AND THE WATERLOO MEDAL. THE STONE IS PLACED OVER HIM BY A FEW FRIENDS

The Grosvenor Museum houses the largest collection of Roman tombstones from a single site in Britain. With a few exceptions, all the stones in the gallery had been reused at some time to repair the City Walls. The tombstones on display tell you something about the lives of the soldiers, slaves, women and children who lived in Roman Chester. Chester has a Military Museum which is particularly concerned with the Cheshire Regiment, the Militia and various associated units including the Cheshire Yeomanry, the 3rd Carabiniers, the 5th Royal Iniskilling Dragoon Guards and the Eaton Hall Officer Cadet School. The Medical Museum contains a permanent collection of curiosities from the world of medicine, nursing, midwifery and social work which features an original letter from Florence Nightingale, written from the Crimea in 1856. The "First World War: Returning Home" exhibition commemorates the 100-year anniversary of the conflict and provides an insight into what a soldier invalided back from the Front would have found on his return to Cheshire. Using local examples wherever possible, the exhibition covers aspects such as the psychological effects of war.

HMS Chester was a "Birkenhead" class light cruiser (sometimes called a "Town" class) fought as part of the 3rd Battle Cruiser Squadron at Jutland. Those killed on the Chester included John Travers Cornwell (VC) (8 January 1900 – 2 June 1916), - who died aged 16. Other elements of naval military history in Chester include the "Galeka Bell" which was salvaged from a WWI hospital ship, SS Galeka.

Military People & Places

The perspective taken below is based on what can be seen/visited as well as the military characters associated with Chester and Cheshire. Cheshire has no particular claim to fame as regards the development of military technology or tactics, but its long connection with the military means that some connection with most of these developments can be found locally. There is a considerable interplay between social structure and military tactics with each able to cause changes in the other and Chester and it's environs provide many examples of this. One reason for this is the location of Chester on a natural border defined by the local geology and hydrology (see: Road Transport). For a non-military history of Chester see "A Short History".

Before the Romans

Hill forts in Britain are known from the Bronze Age (for more see: Before The Romans), but overall the great period of hill fort construction was during the Iron Age, between 200 BC and the Roman conquest. Although there are over 1,300 hill forts in England, they are concentrated in the south of the country, with only a few in Cheshire. Eddisbury is the largest and most complex of the Cheshire hill forts. The Cheshire hill forts differ from the southern hill-forts in one important respect: they belong to the late Bronze Age and the early to mid Iron Age. It has been suggested that the once widespread view that the Cheshire area was a hillfort dominated region at the time of the Roman invasion is false - an alternative view is that the hillforts were built early and abandoned by the Middle Iron Age (i.e after c500 BC). The forts form two geographical groups of three, with Maiden Castle (Bickerton) on its own in the south of the county; Eddisbury hill fort is in the southern group with Kelsborrow Castle and Oakmere hill fort. Helsby Hillfort, Bradley and Woodhouses, form the Northern group. Hillforts were not merely military structures, but may have been the locations for trade and storage of high value goods such as livestock, salt or metals. However, their military purpose is illustrated by the elaborate banks around the complex entrances which are unlikely to be purely ceremonial as at Eddisbury Hill and Maiden Castle archaeology has revealed "guard posts" near the entrances supplied with piles of sling stones.

Pits dating from the 4th millennium BC indicate the site of Beeston Castle may have been inhabited or used as a communal gathering place during the Neolithic period. Archaeologists have discovered Neolithic flint arrow heads on the crag, as well as the remains of a Bronze Age community, and of an Iron Age hill fort. The rampart associated with the Bronze Age activity on the crag has been dated to around 1270–830 BC; seven circular buildings were identified as being either late Bronze Age or early Iron Age in origin. Military historians still debate just how the Bronze Age gave way to the Iron Age and whether the nature of the Late Bronze Age collapse was due to different causes in different locations.

The map below shows the different possible boundaries between what was to become Wales and what was to become England: along the line of what was to become "Offa's Dyke", the flood plain of the River Dee and its branches and the Sandstone Ridge (hillforts). On the "Welsh" side were the ancient Decangli with wealth in terms of copper, and on what was to become the English side the Cornovii with wealth in terms of salt and cattle and very little copper to make bronze. The Iron Age is taken to end, by convention, with the beginning of the historiographical record. In Britain, that means with the coming of the Romans togther with a written record which often refers to military activity.

Gallery and Maps

Related Pages

- Before The Romans: early history of Chester and its environs;

- Road Transport: how topography has influenced communication;

The Romans

The Romans had a well-trained, well-equipped, professional army who were also well-housed and well-fed. They were characterised by permanent military bases which were well connected by good roads that allowed for supply and troop movements. Bases had such benefits as bath-houses, hospitals, workshops, sometimes an Amphitheatre and often associated civilian settlements. The City Walls of Chester follow roughly half of the line of the original walls of Roman Chester and much of the street plan is derived from that of the Roman legionary fortress. Many routes of Roman roads are still used by modern travellers and half of the Amphitheatre, constructed for the entertainment of the troops, can be explored. Roman military tactics are known for highly trained manouvre of often seasoned troops, although it would be wrong to think that they were all frequently in battle.

It is likely that the Romans may initially have wanted to establish a permanent border along the Fosse Way (from Exeter to Lincoln) and exploit the peaceful and productive south of Britain, there was still British resistance to Rome from Wales and the North. Late in 47 the new governor of Britain, Ostorius Scapula, began a campaign against the tribes of modern day Wales, and the Cheshire Gap. The Silures of south east Wales caused considerable problems to Ostorius and fiercely defended the Welsh border country. Caratacus himself was defeated in one encounter and fled to the Roman client tribe of the Brigantes who occupied the Pennines. Their queen, Cartimandua was unable or unwilling to protect him however given her own truce with the Romans and handed him over to the invaders in chains. In 52 C.E. Ostorius died and was replaced by Aulus Didius Gallus who brought the Welsh borders under control but did not move further north or west, probably because Claudius was keen to avoid what he considered a difficult and drawn-out war for little material gain in the mountainous terrain of upland Britain.

The precise date at which the Romans began construction at Chester has been the subject of much debate. According to one version, sometime around 74 CE, the then governor of Roman Britain, Sextus Julius Frontinus constructed an "auxiliary fort" at Deva Victrix (Chester). The placement of this fort (at the lowest ford of the River Dee) appears to have been a strategic move by Frontinus with the intent of both blocking the route of any routed British trying to escape to the north, and to guard against help arriving from the Brigantes and other northern tribes. Frontinus was a noted engineer as well as being a governor, and author of De aquis urbis Romae, a history and description of the water supply of Rome. It is not known whether he was involved in providing Chester's Water Supply from the springs at Boughton to the Roman fort, but is is known that at this time lead (such as is used for plumbing) was traded with the Deceangli of north Wales. The lead was probably mined at Pentre.

It appears that the fortunes of Roman Chester varied over the years as troops were moved out, such as to Hadrian's Wall, and at times the city may have been comparatively empty. Despite this, Roman Chester is slightly larger than many other Roman forts and it has been suggested that it was designed as such with the intention of it being the Roman capital of the province had the Romans invaded Ireland. There is very scant evidence for this theory: in places like Drumanagh (interpreted by some historians to be the site of a possible Roman fort or temporary camp) and Lambay island, some Roman military-related finds may be evidence for some form of Roman presence.[

During the Romam period the military government of the provinces of Britain revolted on several occasions, possibly because they contained a relatively large concentration of troops and possibly because they were distant from Rome and isolated by sea. The provinces needed to be recovered from usurpers several times. Eventually, when the Roman Empire collapsed it appears that the Romans left a significant cultural legacy in North Wales and possibly an ecclesiastical legacy in Chester itself. As fortifications go, Roman Chester was a remarkable success. In almost 400 years of history it was never once attacked, let alone taken by force.

Gallery and Maps

Sextus Julius Frontinus (30-103)

Carusius (d.294)

Magnus Maximus (335-388)

Germanus of Auxerre (c.379-c448)

Related Pages

- Roman Chester: a fairly detailed description of the Roman remains to be found in the city and the surrounding area, as well as a history of the occupation of the city by the Romans (some sites charge for entry, and what can be seen varies from a few stones to significant renains);

- City Walls: a guide to the city walls, including both the Roman parts (much reconstructed) and the extension by the Anglo-Saxons (entry is free);

- Roman Festival Trail: the "not to be missed" elements of a visit are the Roman parts of the City Walls, the Amphitheatre (and the nearby Roman Gardens), the Minerva Shrine and the Grosvenor Museum - all of which can be visited for free. We have included some "nearby non-Roman" elements in the tour for information.

- Legio II: what is known about the history of the second legion, includin their time in Chester;

- Legio XX: what is known about the history of the tenth legion, includin their time in Chester;

- Grosvenor Museum: contains the largest collection of Roman tombstones in Britain, some of which are military (entry is free). Has a small shop, with some books;

- Amphitheatre: a guide and history about the remains of the amphitheatre in Chester (entry is free)

Early Modern

With the departure of the Romans societies could not retain the large-scale military organisation that had previously been possible. Large standing defensive armies became impossible to maintain and while rulers could support a core of professional troops any large-scale warfare would require forces to be mobilised from the general population, who were not trained for war. This would have consequences for agriculture and if an army was kept in the field for an extended period this could lead to food shortages afterwards. One early battlefield within easy distance of Chester may be that of Maes Garmon (c.429) - although the location is disputed and there is little to see except a monument with a dubious history. Aggressor forces often consisted of war-bands, who were more experienced but would have lacked the discipline and infrastructure of the Romans. Often, these were raiders who fought for bounty, whether in the form of loot, land or slaves. The Battle of Chester (c.616) was fought at Heronbridge on the outskirts of Chester between a raiding party from Northumbria and a gathering of Welsh forces. The Battle of Brunanburh (937) was possibly fought to the north of Chester, although there is much debate about the location.

Relatively little is known about early Anglo-Saxon military tactics. Between 600-685 there were a number of significant battles between the early Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. These were probably fought on foot. In the literature, most of the references to weapons and fighting concern the use of javelins, spears and swords, with only occasional references to archery. In early conflicts the shield was smaller and troops may have fought in open order. The use of the horse in battle is very unclear and probably only the "gedriht" (personal followers of the chief) would have been mounted, possibly only on the march and they may well have fought dismounted. In later battles, the formation of a shield wall (scieldweall or bordweall in Old English, skjaldborg in Old Norse) was a military tactic that was developed in many cultures. There were many slight variations of this tactic among these cultures, but in general a "wall of shields" was formed by troops standing in formation shoulder to shoulder, holding their shields so that they abut or overlap. Each soldier benefits from the protection of his neighbours' shields as well as his own. In the battles between the Anglo-Saxons and the Danes in England, most of the Saxon army would have consisted of the inexperienced "Fyrd" — a militia composed of free peasants who provided their own weapons. The shield-wall tactic suited such soldiers, as it did not require extraordinary skill, being essentially a shoving and fencing match with weapons.

There were significant border disputes between the Mercians and the Welsh during this period, and the location of the border continued to fluctuate. Mercia reached its peak under Offa (died 29 July 796 AD), who may or may not have built the border structure known as Offa's Dyke, and which may or may not have stretched from the Dee to the Severn. Coenwulf the Mercian died in 821 at Basingwerk near Holywell, Flintshire, probably while making preparations for a campaign against the Welsh that took place under his brother and successor, Ceolwulf, the following year. Ceolwulf II of Mercia defeated and killed Rhodri ap Merfyn (c. 820–878), later known as Rhodri the Great (Welsh: Rhodri Mawr), king of the north Welsh territory of Gwynedd. In 881 Rhodri's sons defeated the Mercians at the Battle of the Conwy, a victory described in Welsh annals as "revenge of God for Rhodri". The Mercian leader was, according to the Welsh histories, "Edryd Long-Hair", almost certainly Ceolwulf's successor as Mercian ruler, Æthelred. The Battle of the Conwy ended the traditional hegemony of Mercia over north Wales and probably contributed to Æthelred's decision to accept the lordship of King Alfred of Wessex. This united under Alfred the Anglo-Saxons who were not living under Viking rule, and was a significant step towards the creation of the Kingdom of England.

Vikings

The Vikings would have a very strong influence on the history of Chester for a period of about 200 years from around 873 to 1066. This does not mean that the Vikings arrived suddenly in 873. They were almost certainly present before that year, although they expanded their presence afterwards. The legacy of this influence would be one factor in the establishment of the Norman eardom of Chester and the establishment of a Palatinate whose existence would echo down the centuries. The Vikings are probably the reason why the City Walls were rebuilt around 907 by Æthelflæd as part of her establishment of a "burh". The "burh" system seems to have the initiative of Æthelflæd's father Alfred. He sprang into burh building after recovering from his near-disaster at Chippenham in an about turn of doing little to fortify Wessex. The were not simply fortresses but fortified communities placed at the junction of trade routes. If each burh was a market town on a trade route it would generate the wealth needed for its upkeep. Before Alfred there was much less urban living in England, with a few exceptional examples being trading ports on the coast. The Anglo-Saxons may well have even feared the ruins of the Romans. The creation of the Burh would in turn create the "Burgher" the new middle-class of citizen with independent wealth created through trade. Æthelflæd's refortification of Chester was part of a larger strategic intent. At the time the Danes had occupied much of the North Sea coast and were in a position to threaten the Mercian political center at Tamworth. Meanwhile the Hiberno-Norse had settled in parts of Wirral and invaded much of coastal Lancashire and Cumbria. The Cheshire plain offered an easy line of approach to Tamworth assuming landings along the Dee and Mersey estuaries, so Æthelflæd and her brother built a line of "burhs" (fortified sites) at Chester, Eddisbury, Runcorn and Manchester. Upon succeeding her husband, she began to plan and build a series of fortresses in English Mercia, ten of which can be identified: Bridgnorth (912); Tamworth (913); Stafford (913); Eddisbury (914); Warwick (914); Chirbury (915); Runcorn (915). Three other fortresses, at Bremesburh, Scergeat and Weardbyrig, have yet to be located. At Chester and Manchester this involved the use of Roman fortifications, whereas at Eddisbury an Iron-Age hill-fort was re-used.

Gallery and Maps

Ecgbert (c771-89)

Hastein (fl.894)

Æthelflæd (870-918)

Edward the Elder (c870-924)

Æþelstān (c.894 – 27 October 939)

Edgar the Pacific (c943-975)

Olaf II (c. 995 – 29 July 1030)

Leofric (c1000-1057)

Harold see: Hermitage (c1022-1066(?))

Related Pages

- Mold Cope

- Battle of Chester

- Viking

- Olaf II: saint or psychopath?;

- Battle of Brunanburh: fought near Chester?;

- Amphitheatre: where Alfred fought Vikings?;

- Ælfgar: the end of the Dark Ages from a Mercian perspective;

- Dark Ages: from Rome to Hastings;

- Æthelflæd: warrior queen who was written out of history;

- Ecgbert;

- Chester in 900;

- Harold's family;

Medieval

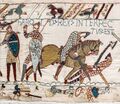

It is a bit of a stretch to claim that the Normans were the originators of the use of heavy cavalry in the European context. However, they undoubtedly perfected the concept and made the most of it: their use of cavalry features prominently in the Bayeux Tapestry (technically it is embroidered rather than woven). In the Early Middle Ages in Europe, knighthood was conferred upon mounted warriors. During the High Middle Ages, knighthood was considered a class of lower nobility. Since only the noble classes could afford the expense of knightly warfare, the supremacy of the mounted cavalryman was associated with the hierarchical structure of medieval times, particularly feudalism. As the period progressed, however, the dominance of the cavalry elite began to slowly break down. By the Late Middle Ages, the rank had become associated with the ideals of chivalry, a code of conduct for the perfect courtly Christian warrior and was progressively detatched from its original military significance. In later times the Cheshire gentry would develop a particular obsession with any descent from Norman ancestors and the coats of arms which resulted from this descent.

Castles

The Normans were also noted castle builders. European-style castles originated in the 9th and 10th centuries, after the fall of the Carolingian Empire resulted in its territory being divided among individual lords and princes, often as a reward for military service. These nobles built castles to control the area immediately surrounding them and the castles were both offensive and defensive structures; they provided a base from which raids could be launched as well as offered protection from enemies. In its simplest terms, the definition of a castle accepted amongst academics is "a private fortified residence". This contrasts with earlier fortifications, such as Anglo-Saxon burhs; castles were not communal defences but were built and owned by the local feudal lords, either for themselves or for their monarch to defend a relatively small number of people.

The Normans built a line of defence from the Dee Estuary southwards to defend Cheshire from the Welsh and possibly to tax trade at the border. It ran roughly NW to SE and comprised at least nine Cheshire Castles starting with (1) Shotwick on the North side of the Dee, then (2) Chester Castle, (3) Dodleston, (4) Pulford, (5) Aldford, (6) Holt, (7) Shocklach, (8) Malpas and (9) Oldcastle. Beeston Castle is something of an exception, possibly being a largely political statement by Ranulf de Blondeville. There is something to be seen at all of these sites, but the remains vary from small remaining eathworks to substantial castle remains. One thing worth noting is the relatively small size of these castles as compared with the hill-forts of the pre-Roman period and the defensive Burh of Anglo-Saxon times.

Hugh of Avranches and the later Norman Earls of Chester were frequently at war, often with the Welsh for control of teritory in Flintshire and the rest of North wales. For several centuries Chester would continue to be a starting point for invasions of North Wales, either by the earls or later by kings. Their most obvious monument to this military past in Chester is Chester Castle, which is unfortunately not often open to the public. Little survives of the castle from the medieval period, with only the Agricola Tower being from this time although its name derives from a false association with the Romans. The institution of the Earls of Chester has its roots in the later Dark Ages where the "ealdormen" of Mercia had significant power. This influence, and a considerable degree of autonomy from the crown continued into the Medieval period and was in part brought about by the need for a strong military presence on the border with Wales. Particularly warlike Earls included Ranulph De Gernon and Ranulf de Blondeville with the former using a degree of audacity and opportunism and the latter being more politically skillful. One notable military exploit occured during King John’s Welsh wars of 1210-12. In 1211, Roger de Lacy (Constable of Chester) rescued Ranulf de Blondeville from Llywelyn's siege at Rhuddlan by collecting a body of "players, fiddlers and other loose persons" from the midsummer fair and marching this rag-tag force towards the seige making as much noise and raising as much dust as possible. The besiegers fled in the face of what they believed to be a sizable and well-armed force. How true the story is remains uncertain although in folklore it forms the basis for the tradition of the so-called Minstrel Court at Chester.

The Earls of Chester were indeed a law unto themselves. In many ways Cheshire stood apart from England. Although the importance of the county’s absence from the Pipe Rolls has been minimized by some scholars, that absence reflects a considerable degree of independence. The king's writ did not run to Cheshire. The chief administrative official, the justice of Chester, was at times neither appointed by the king nor responsible to him. The king derived no benefit from scutages or tallages levied in the county. Royal justices did not visit it; fines and amercements levied there did not reach the king. Eventually it became clear to the king that the earldom was simply too powerful and the titles were effectively siezed by the crown and became the personal fiefdom of the male heir to the throne who was both "Prince of Wales" and Earl of Chester.

The years 1264-5 brought the Second Barons' War to Chester, provoked ostensibly by Henry III's demands for extra finances, but which marked a more general dissatisfaction with Henry's methods of government on the part of the English barons, discontent which was exacerbated by widespread famine.

Samuel Lewis states:

- "Chester was captured by the Earl of Derby, in the year 1264, and held for the crown till the battle of Evesham, in which the barons were defeated with the loss of their leader, and an end put to the contest."

In fact, while the City was captured the Castle was not. In 1265, during the Second Barons' War, the royalist supporters of Henry III, James of Audley and Urien of St. Pierre, besieged Luke de Taney, Simon de Montfort's justice of Chester, in Chester Castle for ten weeks. Taney surrendered upon news of de Montfort's defeat at Evesham, and Prince Edward himself occupied Chester, from where he sent out instructions described as his "first recorded act of state" as a "responsible adviser of the Crown", while not getting on with the Abbot and consuming his wine. The whole business is recorded in the Chester Chronicle as follows:

- "Dominus autem Eadwardus apud Herford die Jovis in Septimana Pentecostes de custodia Domini Simonis de monteforti evasit. Quo audito Jacobus de Audethlegio et V.de Sancto Petro, Sabbato sequenti castrum de Beuston nomine domini Edwardi ceperuntetdie Sancte Trinitatis Cestriam venientes de consilio civium, Lucam de Taney cum suis complicibus infra castrum Cestrie obsederunt per decem Septimanas continuas nec tamen illud obtinuerunt propter optimam inclusorum defencionem. Jacobus de Audethlegio factus est Justiciarius. Dominus vero Eadwardus interim associatis sibi Gilberto de Clare et aliis commarchionibus suis Simonem de Monte forti Henricum filium ejus Hugonem Disspenser, Petrum de Monte forti, Radulfum Basset et eorum complices sæpius [d]ebellavit et tandem eos apud Evsham ij. non. Maii in bello campestri prostravit: Winfridum de Bon, Henricum de Hasting, Guydonem de Monte forti in ipso bello captos apud castrum de D.(?) Beuston secum ducendo captivos. Audiens autem Lucas de Taney dominum Edwardum apud Beston venisse ij vigilias Asumpcionis castrum Cestrie reddidit eidem se suosque gratie sue subjiciendo. Quos idem Edwardus ad tempus incarceravit. Et postea paulatim et successive liberavit. Cumque dominus Edwardus multum irasceretur erga Simonem Abbatem Cestrie ingressum monasterii diucius precludens eidem, et multas intentans ei minas eoquod de licencia Domini Simonis de Monte forti et ipso inconsulto promotus esset tandem in primo ejusdem Abbatis adventu apud Beuston vigilia Asumpcionis contra spem multorum, dominus Edwardus divina inspiratione compunctus, ipsum Abbatem clementer admisit et de consilio domini Jacobi de Audithlegio tunc Justiciario Cestrie exitus monasterii adeo plene jussit eidem restitui, quod pro duobus doliis vini Abbatis tempore iracundiæ in familia ipsius domini Edwardi expensis: Alia duo dolia de Castro Cestrie extrahi et eidem reddi fecit Abbati." - But the lord Edward [the king's son] escaped from the custody of Simon de Montfort at Hereford on the Thursday [May 28] in Whit Week. When this was known James de Audley and Urian de Saint Pierre on the following Saturday seized the castle of Beeston in the name of the lord Edward, and coming to Chester on Trinity Sunday, they besieged Lucas de Taney and his accomplices in the castle of Chester for ten consecutive weeks, but did not succeed in taking it, on account of the excellent defence made by the besieged. James de Audley was made justiciary of Chester. In the meantime the lord Edward, Gilbert de Clare and others his fellow marchers being joined with him, made frequent attacks upon Simon de Montfort, Henry his son, Hugo Despencer, Peter de Montfort, Ralph Basset, and their accomplices, and at length completely overthrew them on the battlefield of Evesham on May 6. Humphrey de Bohun, Henry de Hastings, and Guy de Montfort, who were captured in this battle, Edward took with him as prisoners to Beeston castle. When Lucas de Taney heard that the lord Edward had come to Beeston, he surrendered the castle of Chester on the day before the eve of the Assumption [August 13], submitting himself and his companions to Edward's grace. For the time the same Edward imprisoned them, and afterwards gradually and successively liberated them. The lord Edward however was much enraged with Simon, abbot of Chester, for a long time refusing him access to the monastery, and holding out many threats to him, because he had been promoted by the licence of the lord Simon de Montfort, and without Edward having been consulted. At length, on the arrival of the same abbot at Beeston, on the vigil of the Assumption [August 14], the lord Edward contrary to the hope of many, but moved by divine inspiration, graciously admitted the said abbot, and by the advice of the lord James de Audley, then justiciary of Chester, commanded the revenues of the monastery to be so fully restored to him, that for two casks of wine consumed in the household of the said lord Edward, during the time of his anger against the abbot, he caused two other casks to be taken from the castle at Chester, and restored to the said abbot.

While de Montfort had held Chester Castle (see Earls of Chester), he had reached an arrangement with Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, something that Edward would neither forget nor forgive.

The late 13th and early 14th century probably saw the peak of Chester's prosperity in the Middle Ages. Though there was a corn market in Eastgate Street by the 1270s, and though some corn was undoubtedly grown in the county and by the citizens themselves in the town fields, considerable quantities of wheat and barley were brought in from further afield, principally Ireland. The grain was not simply for home consumption: the city also acted as a center for distribution throughout it's region. Although trade with the native Welsh was suspended during Edward I's campaigns, such disruption was more than counterbalanced by the citizens' provisioning of the English armies. Edward I used Chester as his base for military campaigns against North Wales in 1277 and 1282, and hundreds of masons, carpenters and labourers employed to build the "Welsh" castles had their winter billet in Chester. Wealthy merchants could embark on a building boom with some of the country's most highly skilled craftsmen on hand. One such architect was Richard the Engineer, who was at times a builder of Edward's castles in Wales and mayor of Chester.

The Castles and Town Walls of King Edward in Gwynedd is a UNESCO-designated World Heritage Site distributed through North wales. It includes the castles of Beaumaris and Harlech and the castles and town walls of Caernarfon and Conwy. UNESCO considers the sites to be the "finest examples of late 13th century and early 14th century military architecture in Europe". Edward defeated the local Welsh princes in a major campaign and set about permanently colonising the area. He created new fortified towns, protected by castles, in which English immigrants could settle and administer the territories. Flint is a good example of one such fortified settlement: the town did not have a wall, but a protective earthen and wooden palisaded ditch. The outline of this remained visible in the pattern of streets until the mid-1960s. In essence, it was an adaption of the "Burh" system pioneered in the region by Æthelflæd. The conquest and settlement of North Wales was hugely expensive and stretched royal resources to the limit. For much of the 20th century, the castles and walls were considered primarily from a military perspective, but historians now recognise the sites' roles as palaces and symbols of royal power. The location of castles such as Caernarfon and Conwy were chosen for their political significance as well as military functions, being built on top of sites belonging to the Welsh princes. The castles incorporated luxury apartments and gardens, with the intention of supporting large royal courts in splendour. Caernarfon's castle and town walls incorporated expensive stonework, probably intended to evoke images of Arthurian or Roman imperial power in order to bolster Edward's personal prestige.

Archers

The traditional independence that Chester had under the earls was confirmed by a charter of Richard II in 1398 stating that "the said county of Chester shall be the principality of Chester" (with Richard as Prince protected by the "Cheshire Guard" - who seem like a bunch of thugs). The "Cheshire Guard" were not knights and may well have risen to prominence as Richard progressively alienated his nobility, forcing him to rely on troops of lesser social rank. The use of archers had been exploited to great effect by Richard's father, the Black Prince. There were many traditions associated with archery in Chester, some of which are recorded in Chambers "Book of Days".

These troops could not afford to maintain horses. Tactically there were only two ways for infantry to beat cavalry in an open field battle: firepower and mass. Firepower could be provided by swarms of missiles, such as arrows. Mass could be provided by a tightly packed phalanx of men. The traditional role of archery on the medieval battlefield was to begin the action, advancing in front of the main body of the army, as occurred at the Battle of Hastings. This continued to be a standard tactic, particularly in the absence of enemy cavalry. In the British Isles, bows have been known from ancient times, but it was among the tribal Welsh that proficiency in use and construction of the "English" longbow became highly developed. Using their bows, the Welsh forces inflicted a heavy toll on the English invaders of their lands. Adapted by the English following Edward's campaigns in Wales, the longbow was nevertheless a difficult weapon to master, requiring long years of use and practice. Even bow construction was extended, sometimes taking as much as four years for seasoned staves to be prepared and shaped for final deployment. A skilled longbowman could shoot 12 arrows a minute, a rate of fire superior to competing weapons like the crossbow or early gunpowder weapons.

In the last years of Richard II's reign Chester Castle became a favoured royal base. In 1396 the office of master mason, which had lapsed in 1374, was reintroduced, and in 1397 the office of "Keeper of the king's artillery" in Cheshire and Flintshire first appeared. This foreshadowed the dominance of gunpowder, which would have a huge impact on warefare. Chester as a principality was not to last - in 1399, while Richard II is away on a military campaign in Ireland, Henry Bollingbroke, later Henry IV, landed in Britain after exile and took Chester without a fight. Henry captured Richard II who was briefly imprisoned at Chester Castle. Legends still exist that Richard's Royal Treasure is hidden down the well at Beeston Castle.

In 1403, Sir Henry Percy ('Hotspur'), lately justice of Chester, stayed in the city and raised the standard of revolt there, where former kings men and veterans of the Cheshire Guard, the household guard of the the deceased & dethroned ‘Good King Richard’, King Richard II, still resided by the hundreds. Percy formed an alliance with the Welsh rebel, Owain Glyndŵr. Before they could join forces, Hotspur was defeated and killed at the Battle of Shrewsbury as he raised his visor to get some air (he was wearing full plate) and was hit in the mouth with an arrow. Legislation of 1403, vigorously supported by the mayor of Chester, denied any arms to the Welsh - except a knife to eat with. It is from this time that the Shoot the Welsh story comes from. In the weeks following the Battle of Shrewsbury the insecurity of both the new dynasty and some of the city authorities (i.e. those who had been on the King's side at the battle) was demonstrated in the instructions issued by Prince Henry in response to further defections in north Wales. On September 4, 1403, he wrote to the Mayor, Sheriffs and Aldermen of the City of Chester, who were required to impose a curfew upon all Welshmen visiting Chester, and to ensure that they left their arms at the city gates and did not gather in groups of more than three; all Welsh residents were expelled and any who stayed overnight were threatened with execution. Apparently, the actual wording was that: "all manner of Welsh persons or Welsh sympathies should be expelled from the city; that no Welshman should enter the city before sunrise or tarry in it after sunset, under pain of decapitation.". A local story is that it is still legal to "shoot the Welsh" (it isn't!).

There were three components to the so-called "military revolution" occurring at the end of the Middle Ages; a resurgence in the importance of infantry to the detriment of heavy cavalry, increasing use of gunpowder weapons on the battlefield and sieges, as well as social, political, and fiscal changes allowing the growth of larger armies. The first of these components to manifest itself was the "infantry revolution", which developed during the 14th century. Over the course of the century two effective infantry systems developed; the infantry block, armed with spears and polearms, and the practice of combining dismounted men-at-arms with infantry using ranged weapons, typified by the English longbowman. It would be wrong to assume that the infantry revolution swept heavy cavalry from the field. Improvements in armour for man and horse allowed cavalry to retain an important role into the 16th century.

The Wars of the Roses saw artillery like culverins used to supplement infantry attacks and bombards used in sieges but were largely fought without major use of gunpowder. Chester dud not play a direct part in the wars. In 1455 Queen Margret may have visited Chester to gather support for the Royalist cause. It appears that Thomas Stanley, Constable & Justice of Chester, mobilized a large force from Cheshire to help the Lancastrian cause (but arrived too late for the Battle of St Albans to be of help). Richard, Duke of York became Earl of Chester in 1460 despite the fact that Edward of Westminster was still alive: shortly thereafter Richard was killed at the Battle of Wakefield.

Gallery and Maps

Gherbod the Fleming (c1035-1101(?))

Hugh of Avranches (c1047-1101)

Richard of Avranches (c1094-1120)

Ranulf de Meschines (c1074-1129)

Ranulph De Gernon (c1100-1153)

Hugh de Kevelioc (c1147-1181)

Ranulf de Blondeville (c1172-1232)

John Canmore (c1207-1237)

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307)

Edward II] (1284-1327(?))

Richard II] (1367-c1400)

Related Pages

Gunpowder

The 1320s seem to have been the takeoff point for guns in Europe according to most modern military historians. Scholars suggest that the lack of gunpowder weapons in a well-travelled Venetian's catalogue for a new crusade in 1321 implies that guns were unknown in Europe up until this point. However, from the 1320s guns spread rapidly across Europe. The later part of the 15th and early-16th centuries was a period of great experimentation and innovation in the technology of gunpowder weapons, something confirmed by the variation in type and size of munitions fired at, for example, the Battle of Bosworth. The Civil War came at a time of transition from armies being equipped with bows and lances to the era of pike and musket, from an army called-up only in time of war to a well-trained standing army and the emergence of the army as a distinct political unit which could defy both Crown and parliament. As was often the case in Chester the course of events was influenced by the peculiar status of the city as a distinct administrative unit from the county.

In the Late Middle Ages, the shield was abandoned in favor of polearms carried with both hands (and often partial plate armor), giving rise to the pike square tactics. A pike square generally consisted of about 100 men in a 10×10 formation. While on the move, the pike would be carried vertically. However, the troops were drilled to be able to point their pikes in any direction while stationary, with the men in the front of the formation kneeling to allow the men in the center or back to point their pikes over their heads. While stationary, the staff of each pike could be butted against the ground, giving it resistance against attack. Squares could be joined together to form a battle line. If surrounded, pikes could still be pointed in all directions forming a "hedgehog". A well drilled square could change direction very quickly, making it difficult to outmaneuver on horseback. The pike square dominated European battlefields and influenced the development of tactics well into the 17th century. Even when muskets became common, their slow rate of fire meant that soldiers armed with them were vulnerable to cavalry; to combat this, some soldiers continued to carry pikes until the improving performance of firearms and the introduction of the bayonet allowed armies to drop the use of pikes. It would be many years before the invention of the socket bayonet in the late 17th Century would bring about another major change in tactics.

Perhaps most important, producing an effective arquebusier required much less training than producing an effective bowman. Most archers spent their whole lives training to shoot with accuracy, but with drill and instruction, the arquebusier was able to learn his profession in months as opposed to years. This low level of skill made it a lot easier to outfit an army in a short amount of time as well as expand the small arms ranks.

The Tudors

This idea of lower skilled, lightly armoured units was the driving force in the infantry revolution that took place in the 16th and 17th centuries and allowed early modern infantries to phase out the longbow. An arquebusier could carry more ammunition and powder than a crossbowman or longbowman could with bolts or arrows. Once the methods were developed, powder and shot were relatively easy to mass-produce, while arrow making was a genuine craft requiring highly skilled labor. Ultimately, the arquebus became the dominant projectile weapon of the early renaissance because it was easier to mass-produce and easier to train unskilled soldiers in its use. As musket technology evolved, the flaws of the musket became less frequent and the bow became irrelevant. The Tudor period saw the gradual evolution of England’s medieval army into a larger, firearm-wielding force supported by powerful ships and formidable gun forts to protect the country from the threat of invasion. By 1547, English forces were slowly equipping with new personal firearms, which could be operated by less sturdy men (and after briefer training) than longbow archers. Bronze and wrought-iron artillery was commonplace, and a few cast-iron pieces were appearing on land and in warships. Most importantly, by the end of his reign Henry VIII had built a powerful Navy Royal of warships, purpose-built to carry heavy guns, as his first line of defence against invasion.

The "Trained Bands" were local Militia regiments organised on a county basis and trained in the basics of formation integrating the offensive use of shot and the defensive use of pikes. All this fighting meant that local militia were continually drafted (especially to Ireland) and new weapons and tactics were employed. Matchlock muskets and calivers replaced longbows and were used in combination with the long pike, which gradually replaced the bill. Tactically, much fighting was small-scale, consisting of surprise attacks and siege warfare, with few large battles. Although not involved in the rebellions following the Reformation, the city took precautions as fear of a Spanish invasion mounted during the mid 1580s: military supplies were purchased, foot soldiers trained, and a watch was kept for hostile shipping in the Dee. The defeat of the Armada was duly celebrated, but the authorities remained cautious and in the early 1590s required new freemen to arm themselves, reviewed the trained bands, and inspected munitions stored locally. After the outbreak of the second Desmond rebellion in Ireland in 1579 Chester was the main port used for sending English troops levied in other parts of the country, who passed through the city frequently and in growing numbers. The mayor and other officials were often fully occupied with receiving them and arranging quarters, food, and money. Ships were requisitioned and provisioned, and supplies of food, drink, stores, and ammunition were sent to Ireland. The repeated demands strained local markets, especially during the shortages of the later 1590s: prices rose, ships' masters demanded large payments, there were difficulties with the authorities of Liverpool, disaffected men deserted in droves and were rarely captured, weapons were often found to be defective, moneys were embezzled, profiteering was rife, and Chester earned a reputation as a "robber's cave".

Civil War

By the eve of the Civil War it was no longer necessary for an effective soldier to have the means to support a horse and provide himself with armour or the years of training needed to effectively use a bow.

The popular view was that by the time war actually broke-out the Trained Bands were inefficient, poorly equipped and badly drilled and disciplined. During autumn 1640, with the Scottish army in northeastern England, the Chester Assembly set up a nightly watch, strengthened the defences at the Eastgate, Newgate, and Bridgegate, and ordered members of the corporation and others to supply corselets, muskets, halberds, and calivers within a month. Arrears of an earlier assessment to replenish the magazine were called in, and ordnance and their carriages were brought from Wirral. The trained bands were to be brought up to their full strength of 100 men and placed under the captaincy of Alderman Francis Gamull. There were no military threats during the following months, but the Assembly did not meet between December 1640 and June 1641. Defensive preparations remained half-hearted, with the arrears for the magazine never fully collected, and funds for repairing the city walls having to be borrowed from the proceeds of the prisage on wines until an assessment could be levied. Later in 1641, when the Assembly was transacting very little business, it faced growing threats to public order. First, the arrival of protestant refugees from the Irish rebellion set off anti-popish hysteria, supposedly culminating in January 1642 in a skirmish just outside the city between Catholics and Protestants, with loss of life on both sides. By then troops bound for Ireland had begun to arrive in the city, and the authorities were embroiled in the usual problems: shortage of shipping and delays in embarking troops, unruly and violent behaviour by waiting soldiers, rising prices of food and fodder, and delays in repayment for quarters.

The prevailing mood in Chester in summer 1642 was a wish for accommodation between Charles I and parliament, reflected in the city's neutralist petition in August and in its reaction to the parliamentary commission of lieutenancy and the royal commission of array. The Assembly stood fast against both an attempt by James Stanley, Lord Strange, to secure the county magazine in the castle for the royalists, and Alderman William Edwards's and Sir William Brereton's effort to take control of the city's trained bands for parliament. The decisive event, however, was the arrival of the king himself in Chester on 23 September. In an upsurge of loyalty he was greeted with popular enthusiasm, pageantry, bellringing, and a loyal address. The king's supporters seized their opportunity. The houses of known opponents, such as Brereton and Aldermen Edwards and Aldersey, were searched for arms; county gentlemen favourable to parliament were rounded up; and parliamentary supporters in the corporation left. When the king departed five days later, with a gift of money from the corporation, the parliamentarian presence in the city had all but gone, and the royalist hold on Chester had finally been consolidated. Parliament soon realised how important Cheshire was and sent Brereton to raise support for its cause. Geographically Cheshire lies between the Pennines and the Welsh hills and so whoever controlled Cheshire controlled the north – south corridor. For Parliament the control of Cheshire would mean separating the King's northern supporters from the King and his army at Oxford. It would also stop the King bringing in reinforcements from his "Irish army" through the port of Chester. However once the King left Chester there was not much enthusiasm in Cheshire for fighting and something of a stalemate ensued. There were even meetings between member of the county elite at Tarporley and Bunbury with a view to signing a peace treaty. At these meetings the Royalists were represented by Lords Kilmorey and Cholmondeley and the Parliamentarians by Henry Mainwaring and William Marbury (with Orlando Bridgeman replacing the latter at Bunbury). A Bunbury Agreement of sorts was actually signed on the 23rd December 1642 which envisaged a cessation of conflict, exchange of prisoners and destruction of the fortifications of Chester. Unfotunately there was too much local distrust for the treaty to last and it was entirely unsupported by either the King or Parliament.

The story of the Civil War is told elsewhere on these pages, but effectively Chester came under a prolonged siege with a significant battle in the middle of it. Brereton invested Chester at a distance using the good roads between the salt-towns of eastern Cheshire to establish his position. He then began to close slowly on the city. In September 1645 the royalists lost Bristol, depriving Charles of a connection with Ireland. When Boughton fell later the same month and the besiegers becan to move their ordinance into Foregate Street, Charles sought to relieve Chester from the slowly contracting circle of Parliamentary forces. Charles entered Chester on the 23rd September with his "Lifeguard of Horse". On the same day, 1,500 Royalist cavalry arrived at Rowton Heath. At dawn the next day the main Royalist force crossed Holt Bridge. By nightfall, the Royalists were defeated before the walls of Chester in what was to be one of the last battles of the first civil war. Charles spent the night at Gamul House then left Chester in retreat to Denbigh, along an undefended road, accompanied by only 500 horse.

In Januaty 1646 an agreement for surrender of Chester was reached. The sick and wounded were allowed to stay in the city until they recovered, and the able bodied could leave in safety. On the 3rd February Lord Byron at Chester finally surrendered. The Parliamentary leaders had promised to respect ancient buildings and Churches in Chester. But when their soldiers marched through the City Gates in triumph, they ran wild. During the Parliamentary occupation of Chester many Churches were damaged, and the High Cross where Brereton had beaten the drum to recruit for Parliament and been arrested by Thomas Cowper was destroyed. Sir Francis Gamull, now the mayor, bargained with the Roundheads that the tombs of his family should not be harmed, and this explains the fact that the Gamull monuments in St Mary on the Hill are almost the only relics of the kind in Chester that escaped destruction.

Restoration, Revolt and Revolution

Chester played an unsuccessful part in several military ventures during the later 17th century.

Roger Whitley (1618 – 17 July 1697) was a royalist officer in the English Civil War, attaining the rank of Major General (2nd in command of their forces in the battle for the Isle of Anglesey) and was closely involved throughout the 1650s in plans for a royalist uprising against the Interregnum and Protectorate regimes. He had accompanied the young King Charles II into exile and carried the kings orders into Cheshire on the rising of forces, under George Booth, at the eve of the Restoration. What has become known as "The Booth Rising" was arranged for 5 August 1659 in several districts, and Booth received a commission from Charles II to assume command of the revolutionary forces in Lancashire, Cheshire, and north Wales. Booth's Rising can be seen as a key trigger for Monck's march on London and the Restoration of Charles II, but is often written-off as wholly unsuccessful.

The Monmouth Rebellion, was an attempt to overthrow James II. Prince James, Duke of York, had become King of England, Scotland, and Ireland upon the death of his elder brother Charles II on 6 February 1685. James II was a Roman Catholic and some Protestants under his rule opposed his kingship. James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth, the eldest illegitimate son of Charles II, claimed to be rightful heir to the throne and attempted to displace his uncle. Several areas of England were considered as potential locations for rebellion, including Cheshire and Lancashire along with the South West, as these were seen as having the highest number of opponents of the monarchy. Monmouth visited Chester in September 1682 but any plans to arrange a rebellion in Chester came to nothing when Monmouth landed in 1685 and was defeated at Sedgemoor.

James II features in the scultures at the Town Hall in a somewhat misleading description of him being feted by the Assembly. This shows James II on his Visit to Chester in 1687. Mistrust of the king was evident during his visit to Chester in August 1687, to the extent that the Governor of Chester was unable to procure a loyal address from the corporation - not much of a welcome really. In August 1688 the government of James II removed the entire Assembly including Tories Grosvenor and William Stanley, earl of Derby, and obliged the city to petition for a new charter, which named the corporation and principal officers, reserved the Crown's right to dismiss individuals, dispensed all members from the prescribed oaths, and restricted the parliamentary franchise to the corporation. Of the 24 aldermen named in addition to the mayor and recorder only 11 had already served as aldermen and four as sheriffs. The attempt to conciliate Whigs and nonconformist protestants was fruitless: the nominated corporation apparently never met. James' interest in Chester clearly illustrate the local political volatility at the time.

1688 brought the "Glorious Revolution" when William of Orange, landed (5th November 1688) an invasion army from the Netherlands. Chester was the scene of the only spontaneous resistance to the Revolution. On the news of the landing of William of Orange, the Roman Catholic Lord Molyneux with two Irish regiments seized Chester Castle, but on 18 December 1688 the Earl of Derby entered the city, which had declared for the Prince, and Molyneux’s forces were disarmed and disbanded. 1688 would be the last time that there would be any military conflict at Chester.

The Cheshire Regiment

In 1689, Henry Howard, 7th Duke of Norfolk raised a regiment on the little Roodee in Chester in an effort to resist any attempt by James II to re-take the English throne. For the early part of its formation, the regiment was known by the name of the current Colonel-in-Chief, later becoming known as the 22nd Regiment of Foot. In the same year that it was raised, the regiment saw its first action as part of a British force sent to Ireland under the command of General Frederick Schomberg (commander-in-chief of the Williamite War in Ireland expedition against the Jacobite supporters of James II), taking part in the siege and capture of Carrickfergus. In 1690, the 22nd fought in the Battle of Boyne, and in 1691 at the Battle of Aughrim. The regiment continued to serve as a garrison in Ireland from this point until 1695, when it was sent to the Low Countries for a short time before returning to its duties in Ireland.

Eighteenth-century European armies were built around units of massed infantry armed with smoothbore flintlock muskets and bayonets. Cavalrymen were equipped with sabres and pistols or carbines; light cavalry were used principally for reconnaissance, screening and tactical communications, while heavy cavalry were used as tactical reserves and deployed for shock attacks. Smoothbore artillery provided fire support and played the leading role in siege warfare. Strategic warfare in this period centred around control of key fortifications positioned so as to command the surrounding regions and roads, with lengthy sieges a common feature of armed conflict. Decisive field battles became relatively rare.

In 1702, the Regiment sailed to Jamaica under the colonelcy of William Selwyn, spending the next twelve years in combat duties against the French and native population, both on land and at sea. In 1726 the Regiment was posted to Minorca where it remained for the next 22 years, although a detachment was present at the Battle of Dettingen in 1743, during the War of the Austrian Succession. George II’s horse "bolted" during the battle and ran away. George is said to have "sheltered" under an oak and to have presented an oak leaf to the soldiers who looked after him. The Cheshire Regiment claims this honour (they were in garrison in Minorca at the time - but a detachment was present). Dettingen was the last time that an English monarch was to personally lead his troops into battle. In 1745, with the rebellion of the Young Pretender, the lord lieutenant, George, earl of Cholmondeley, was keen to put Chester in an improved state of defence. Cholmondeley repaired the castle's decayed fortifications and added raised batteries in the inner and outer wards and a platform with a parapet south-east of the great hall. The imposing battery overlooking the river was intended for 12 cannon but only four pieces were mounted. The surveyor Alexander de Lavaux was engaged to draw up a plan to strengthen the fortifications to resist assault by cannon. His scheme, consisted of four bastions joined by outworks flanking the ancient defences, but was never carried out. A survey of the castle in 1745 reported that the armoury contained "a small number of field pieces and royals in good order and with sufficient ammunition".

In the later 18thC. the Castle's military significance declined again. In the reign of George I military stores and ordnance, dating perhaps from the Civil War, were removed to the Tower of London. By 1728, though still commanded by a governor with two companies of invalid soldiers, the castle was described as 'destitute of arms almost for common defence'. The two companies of invalids remained until 1801, when they were disbanded, but the castle was still notionally a garrison until 1843, commanded by a high-ranking governor and lieutenant-governor. The rebuilding of the early 19th century included barracks for 120 men and an armoury capable of storing 30,000 stand of arms.

Global Empire

The loss of the United States, at the time Britain's most populous colony, is seen by historians as the event defining the transition between the "first" and "second" empires, in which Britain shifted its attention away from the Americas to Asia, the Pacific and later Africa. With Chester's Port in decline it took little direct part in warfare although the Leadworks was to supply much shot for European wars after 1800.

When Thomas Gould was with the 52nd at Waterloo then he was present at a key moment in history. The final action of the day saw Sir John Colborne wheel about the 52nd Light Infantry to outflank the never-defeated Old Guard of the French Imperial Guard as they advanced towards the British center to defeat Wellington's almost shattered and exhausted forces. As the French column passed his brigade, the 52nd charged, fired a devastating volley into the left flank of the Chasseurs and then attacked with the bayonet. William Hay, a Light Dragoon watching from the right, later recalled that "so well-directed a fire was poured in, that down the bank the Frenchmen fell and, I may say, the battle of Waterloo was gained". The whole of the French Guard was driven back down the hill and began a general retreat. An earthquake of panic passed through the French lines as the astounding news spread - "La Garde recule. Sauve qui peut!" ("The Guard retreats [recoils]. [let him] save [himself] who can!").

Seeing the 52nd begin an advance, Wellington reputedly ordered "Go on, Colborne, they won't stand!"; the battalion then advanced diagonally across the field. Wellington, seizing the moment, stood in Copenhagen's stirrups, and (as a ray of sunlight supposedly fell upon him) waved his hat in the air to signal a general advance - his army rushed forward from their battered lines and threw themselves upon the retreating French - retreat became rout, and Napoleon's last hopes of a return from exile were extinguished. Tom Gould, common soldier from Chester was there.

Gallery and Maps

William Stanley] (1435-c1495)

Henry VII] (1457-1509)

William Stanley (1561-1642)

Charles II (1600-49): see Civil War

Thomas Cowper (c1600-71)

William Brereton (c1604-61)

Richard Grosvenor (1604-65)

Francis Gamul (1606-54)

James Stanley (1607-51)

George Booth (1622–1684)

James Scott (1649–1685)

Watkin Tench (1758-1833)

Stapleton Cotton (1773-1865)

Related Pages

Mechanised Warfare

If by some miracle Richard III could be whisked away from the last minutes of the Battle of Bosworth to the field of Waterloo, he would have understood what was happening, although between cursing the Stanley's at length, he would have probably suggested that Wellington lead a personal charge at Napoleon. Wellington would no doubt have had a witty riposte. Within a few years Richard would have been completely out of his depth.

It would be difficult to do justice to all of the people from Chester who were caught up in mechanised warfare. The following is a short selection of facts about Chester from this period. There are several excellent books on the subject:

- "Chester at War" by Mike Royden;

- "What did you do in the war Deva?" edited by Emma Stuart;

- "Chester in the Great War" by Susan Chambers;

Mechanised warfare, is the employment of mobile attack and defense tactics that depend upon machines, which in some cases increase the rate at which troops can move, often to give a benefit of surprise. In 1867, Chester Castle was the focus of an audacious plot by Fenians (supporters of Republicanism in Ireland) that ended in farce. Their plan was that around 2,000 men would infiltrate Chester and, under American-Irish command (by officers with experience in the American Civil War), seize a cache of rifles belonging to the Chester Volunteers. These arms would be used to storm the castle, at that time garrisoned by only 60 regular soldiers of the 54th Regiment. The castle arsenal contained 10,000 rifles and 900,000 rounds of ammunition, which the Fenians hoped to obtain. Once armed, the plan was to commandeer a train, take the arms to Holyhead, seize a streamer, sail to Wexford and raise a revolt in Ireland. In effect, the use of trains to bring their forces to Chester and to escape by rail and then steal a steamer was an early example of mechanised warfare to gain the benefits of mobility, despite being an example taken from asymmetric warfare.

Dreadnought

At sea, mechanised warfare saw the introduction of steam power to at first augment and then overhaul sail. The 1840s saw the construction of experimental steam-powered frigates and sloops. The armoured cruiser developed as a type of ironclad specifically for the traditional cruiser missions of fast, independent raiding and patrol. In the 1880s, naval engineers began to use steel as a material for construction and armament. A steel cruiser could be lighter and faster than one built of iron or wood. hortly after the turn of the 20th century there were difficult questions about the design of future cruisers. Modern armored cruisers, almost as powerful as battleships, were also fast enough to outrun older protected and unarmored cruisers. In the Royal Navy, Jackie Fisher cut back hugely on older vessels, including many cruisers of different sorts, calling them "a miser's hoard of useless junk" that any modern cruiser would sweep from the seas. The scout cruiser also appeared in this era; this was a small, fast, lightly armed and armored type designed primarily for patrol and reconnaissance. HMS Chester was a Town-class light cruiser of the Royal Navy, one of two ships forming the Birkenhead subtype. Along with sister ship, Birkenhead, she was originally ordered for the Greek Navy in 1914 and was to be named Lambros Katsonis after a Greek revolutionary hero of the 18th century.

HMS Chester became famous at the Battle of Jutland. Chester was scouting ahead of the 3rd Squadron when, at 5.27, she was ambushed at 6,000 yards by German light cruisers, using intercepted British signals. Chester was hit by 17 150mm shells and suffered casualties of 29 men killed and 49 wounded. Fortunately the 3rd Battle Cruiser Squadron intervened from the north east, surprising the Germans. Invincible (Hood's flagship) disabled Wiesbaden and Regensburg crippled Shark. This intervention by Hood inadvertedly distracted the Germans whilst Jellicoe belatedly deployed the Grand Fleet into the line of battle and thus possibly prevented the Germans from "crossing the Grand Fleets T" before it was deployed.

Those killed on the Chester included John Travers Cornwell (VC) (8 January 1900 – 2 June 1916), - who died aged 16. Although Cornwell survived long enough to reach hospital in Grimsby, he died of his wounds on 2 June. Much propaganda was made out of Jack's death with numerous parallels to the death of Giocante Casabianca at the battle of the Nile (origin of "the boy stood on the burning deck..."). The bible belonging to "Jack" Cornwell is in Chester Cathedral as is a memorial to the ship and it's dead (and the ship's ensign and union flag).

Tanks

The first armored car was the Simms' Motor War Car, designed by F.R. Simms and built by Vickers, Sons & Maxim of Barrow on a special Coventry-built Daimler chassis with a German-built Daimler motor in 1899. These provided limited protection for the crew. The first effective use of an armored vehicle in combat was achieved by the Belgian Army in August–September 1914 in the form of the Minerva. However, the second Duke of Westminster played an important part in British developments with the development of the Rolls-Royce Armoured Car. He took a squadron of these cars to France in time to make a contribution to the Second Battle of Ypres (1915). Fritz Haber had developed a suggestion of the chemist Walther Nernst into chemical weapons and with the assistance of several other Nobel Prize winners released a cloud of chlorine on 22nd April 1915 with horriffic results:

- "...haggard, their overcoats thrown off or opened wide, their scarves pulled off, running like madmen, directionless, shouting for water, spitting blood, some even rolling on the ground making desperate efforts to breathe."

The Germans failed to fully exploit the unexpected success of their first gas attack. In the confused fighting and further gas attacks which followed there is some evidence to suggest that the presence of armoured cars was one factor which prevented a complete rout, but the main factor was the lack of German reserves.

The second Duke's received his DSO in 1916 for a heroic armoured-car rescue of survivors of the ship Tara. Tara was torpedoed by U-35 in Sollum Bay, in the Mediterranean Sea on 5 November 1915. The crew were saved by the U Boat and handed over to Senussi tribesmen as prisoners. On 14 March 1916 they were being held at Bir Hakeim along with the crew of the HMT Moorina, a horse transport. They were rescued by the Duke of Westminster's armoured car brigade, part of the Western Frontier Force (and driving "Rolls-Royce" armoured cars. The captain of the Tara at this time was Capt. R. Gwatkin-Williams, R.N. In his book "Prisoners of the Red Desert, Being a Full and True History of the Men of the Tara" Gwatkin-Williams relates how, after accidentally finding a letter from Captain Gwatkin-Williams to a Turkish officer stating the desperation of the situation at Bir Hakeim, the Duke set off to find the POWs. With a guide who had been to Bir Hakeim some 30 years previously as a boy he set off across the desert estimating that he was about 70 miles away. Passing the 70 mile estimate and running low on fuel he kept going as long as there was any hope, finding the camp after traversing 115-120 miles and resuing the prisoners.

One urban legend in Chester is that the High Cross was once involved in a collision with a Sherman tank. This is completly untrue as the cross was only restored to its present position in the 1970's. However, there is one record of a tank being in the area. A batch of "presentation" tanks were sent round the country at the end of WW1 as "monuments" and as part of the Victory Loan scheme in 1919. One such tank remained on the Town Hall Square until Saturday 12th July 1919 - the 35 ton tank arrived by train a day late due to a broken axle (and is there said to be from the 19th Batt), and did damage the road as it trundled from Chester Station down Brook Street, George Street and Northgate. It was reported as being a tank from the 19th Battalion, but it was confirmed it was formerly a tank that saw service with "I" Battalion (later to become 9th Battalion). The city eventually turned down the offer of a "presentation tank". Urban legend sometome reports that Lloyd George was riding on it, however, the people who rode on it were "the Mayor and his party". The mayor was John M. Frost, who remained mayor through the entirety of WW1.

The MP at the start of WW1 was Robert Yerburgh. At the outbreak of the First World War Yerburgh was suffering from heart trouble and was in the spa town of Bad Nauheim in Germany, with his wife. The couple were not allowed to leave immediately and were initially placed under curfew before being detained as prisoners of war under the orders of the military governor of Frankfurt. Nine weeks later, they were allowed to leave and were sent to Switzerland where they were required to stay for three weeks before returning to England. After his return to England, Robert's health continued to deteriorate and reigned as MP. He died in December 1916, aged 63. His seat was gained unopposed by Owen Philipps a shipping magnate, who held it until 1922. Philipps is remembered in Chester for installing the bell from SS Galeka (a war casualty) on the canal-facing corner of St John's Hospital. He later spent ten months in Wormwood Scrubs for fraud.

War in the Air

In the air, Chester boasts a early military balloonist who is almost forgotten today. That was not Baldwin, who is slightly better known, but Lieutenant George French of the Cheshire Militia (or Captain French in the alternative). Little is recorded about the flight in a Lunardi balloon other than the bare fact that it took place in September 1785, and that French had some problems getting into the air. French rose three yards and then touched down again, so he dumped all his ballast, along with his provisions, hat and coat before taking off on his flight. It is not clear whether French took the flight "for a lark" or whether this was an attempt to assess the possible military applications of aviation. By co-incidence the 2nd Royal Cheshire Milita barracks was in Macclesfield, where French landed some forty miles from Chester - there is no record of how the Militia reacted. However there are hints that French was instrumental in bringing Lunardi to Chester.

In 1917 Leonard Cheshire was born in Hoole Road (in the building which is now the "BaBa" Hotel). Cheshire did not take part in the "Dam Busters" raid but took over command of 617 "Dam Busters" squadron later in the war, and was the official British observer of the nuclear bombing of Nagasaki flying in the support B-29 "Big Stink". Also in Hoole a faded relic of WW2 can be found at the corner of Waverley Terrace and Ermine Road, where "EWS" can be just maked out in large yellow letters. This indicates the location of an "Emergency Water Supply". There are two more of these in Chester, one at the south end of Brook Street and another, as metal signage, in Northgate Street on the frontage of the "Coach House".