Merchant Adventurers

(still work in progress)

- "Krieg ist die Fortsetzung des Geschäfts mit anderen Mitteln" ("War is the forwarding of business with other means" - after Clausewitz)

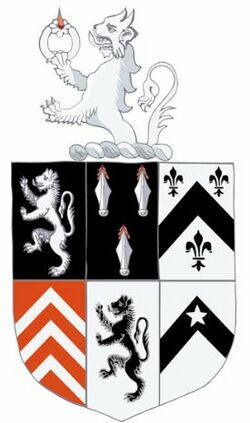

On the front of Bishop Lloyd's House in Watergate Street Chester can be seen a coat of arms relating to the Merchant Adventurers of Chester. This is their story from 1554 to 1639 and explores their possible connection with the "East India Company", an organisation which helped to paint large parts of the map of the world red. Much of this article covers the period around the Tudor/Stuart transition when a major economic shift began to take place from the control of trade being in the hands of local individuals to the establishment of "multi-national" companies which were jointly financed by large groups of people. For more on these two periods see Tudor Chester and Stuart Chester.

Bishop Lloyd's House dates from the middle of the Age of Discovery or the Age of Exploration, part of the early modern period and largely overlapping with the Age of Sail, a period from approximately the 15th century to the 17th century, during which seafarers from a number of European countries explored, colonized, and conquered regions across the globe. The extensive overseas exploration, particularly the European colonisation of the Americas, with the Spanish and Portuguese at the forefront, later joined by the Dutch, English, and French, marked an increased adoption of colonialism as a government policy in several European states.

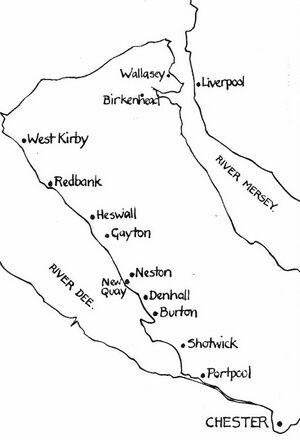

In 1571 the people of Liverpool sent a memorial to Queen Elizabeth I, praying relief from a subsidy which they thought themselves unable to bear, wherein they styled themselves "her majesty's poor decayed town of Liverpool". Some time towards the close of this reign, Henry Stanley, 4th Earl of Derby, on his way to the Isle of Man, stayed at his house. By the end of the sixteenth century, Liverpool began to be able to take advantage of economic revival and the problems of the River Dee to win trade, mainly from Chester, to Ireland, the Isle of Man and elsewhere. In 1626, King Charles I gave Liverpool a new and improved charter. Chester's port declined with most of the ships going from the colonies now going to Liverpool, although it was still the major port of passenger embarkation for Ireland until the early 19th century. A new port for Chester was established on the Wirral at Parkgate, but this also fell out of use.

In York, the Merchant Adventurers' Hall is a unique building in the heart of the city. The Merchant Adventurers' Hall on Fossgate was largely built between 1357 and 1368 on the site of a Norman mansion as the communal meeting hall, chapel and, after 1371, undercroft hospital of the Fraternity of the Holy Trinity. It was granted the status of the Company of Merchant Adventurers of the City of York by Queen Elizabeth I in 1581. The principal parts of the building are the Great Hall, the chapel and the undercroft. The Great Hall is a timber-framed structure and was built over a five-year period. It is the largest timber-framed building in the UK still standing and used for its original purpose. The Hall belongs to and is still regularly used by The Company of Merchant Adventurers of the City of York, who, although no longer dedicated to mercantile activities are prominent in York and still exist as a charitable membership group. Bishop Lloyd's House (or Palace) in Chester has been proposed as the local equivalent.

Bishop Lloyd's House is named after Bishop George Lloyd (1560– 1 August 1615). He was born at Llanelian-yn-Rhos, near the present day Colwyn Bay. His association with Chester probably began when, between June 1575 and September 1579, he was a King’s Scholar at Chester Cathedral. It has been suggested that his brother, the increasingly influential David Lloyd, could have organised this education as he was living in Chester at the time. George attended Jesus College, Cambridge from 1579 to 1582, gaining his degree, and his MA in 1586. In 1596 he gained his DD. He was thirty-six years old and became Divinity Lecturer at Chester Cathedral. The Divinity Lecturer was bound to give two prelections weekly, for which he received a stipend of £40. He was appointed Rector of Heswall in 1597 and appears to have lived there.

George Lloyd was consecrated as Bishop of Sodor and Man in late 1599 (Calendar of State Papers Domestic: Elizabeth, 1598-1601 p. 360) being presented 18 December by William Stanley, 6th earl of Derby. Royal assent by Queen Elizabeth is said to have been signified to the archbishop of York (Matthew Hutton) on 23rd December 1600. Chester and Man were both in the provence of York since an Act of 1541. The State papers make no mention of the Earl’s nomination, and are so worded as to convey the impression that the Queen herself presented Lloyd to the Bishopric. If this were the case, it looks like a decided encroachment on the Earl’s rights, as the original grant of the island to Sir John Stanley conveys the patronage of the See absolutely.

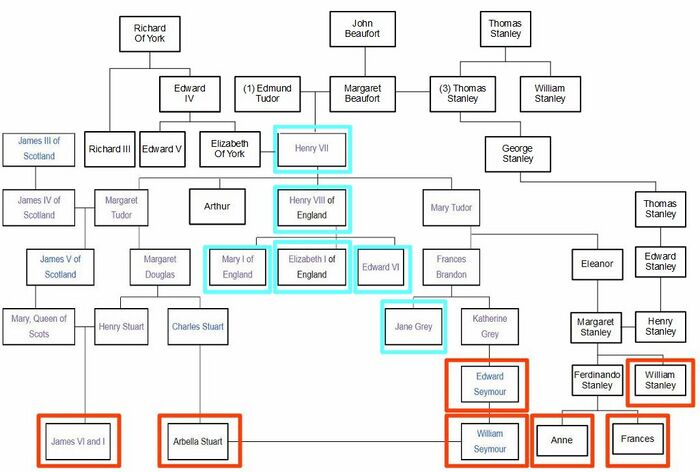

William Stanley (see Shakespeare and Chester) was educated at St John's College, Oxford. In 1582 he travelled to the continent to study in university towns in France and may also have attended Henry of Navarre's academy at Château de Nérac. In 1585 he returned home but was once more sent to Paris as part of an embassy to Henry III of France. He then remained on the continent for a further three years of personal travels before returning home once more. After the death of his father in 1593, William as the second son was bequeathed a number of Manors and Lordships while his elder brother Ferdinando Stanley, 5th Earl of Derby, inherited the Earldom and its estates. From his marriage to Alice Spencer, Ferdinando had his eldest daughter, Anne Stanley, Countess of Castlehaven, in 1580. Henry VIII's will would have made her queen in 1603 as heiress of Henry's younger sister Mary Tudor (Queen of France); Elizabeth was actually succeeded by James VI of Scotland, the heir of Henry's older sister, Margaret Tudor. Ferdinando died (probably murdered) in April 1594, leaving three daughters but no sons.

Like most of his predecessors, Lloyd rarely visited the Isle of Man and there is only one recorded visit in 1603 where he attended a Consistory Court where several offenders against the "Spiritual Laws of the Isle of Man" were punished. The pastoral oversight of the See of Man was no enviable post in the 17th century, it was spoken of as "a place of banishment"; "a melancholy retreat"; "a Patmos"; and "a disconsolate residence." The episcopal income, moreover, was miserably inadequate.

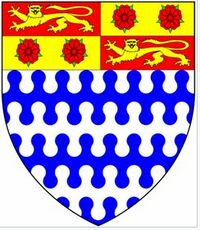

In 1605 he exchanged the seat of Sodor and Man for that of Chester. Between these dates of 1601 and 1605 only, he was entitled to use the arms which appear on Bishop Lloyds house. During his tenure as Bishop of Chester, he reversed the anti-Puritan policies of his predecessor Richard Vaughan, who had by then become Bishop of London. Lloyd was succeed in Man by John Phillips. Lloyd died 1st August 1615. However it is worh mentioning one local history story about Phillips and a Manx Witch Trial. 15th Cent. Ranulf Higden of the Polychronicon had written:

- "in the Ilonde of Mann is sortilege and witchcraft used, for women there sell to shipmen wynde as it were closed under htree knotte of threde, so that the more wynde he would have the more knottes he must undo"

Phillips tried the case of Margaret Inequane (or Ine Quay) whose precise crime is unknown but was related to withchcraft. After being found guilty in the ecclesiastical court by a jury of six drawn from the parishes affected by their alleged practices they were, according to law, handed over to the temporal power by the Bishop’s chief executive officer, the General Sumner. When the jury found the accused guilty Bishop Phillip, who occupied a place among the judges, left the Court to avoid being involved in the shedding of blood. After the departure of the Bishop sentence was pronounced:

- "That she be brought by the Coroner of Glen Faba to the place of execution, there to be burned till life depart from her body."

The burnings of 1617 mark the only time, in the Isle of Man, when the extreme penalty was exacted there for sorcery. And was the subject of the film "Solace in Wicca".

The fact that the plaque bears the arms of the Bishop of Sodor and Man admits an argument which allows it to be dated to the period 1601-1605. The dating could be the subject of considerable debate. It cannot be before he was made Bishop. Were it later, Lloyd would have displayed the arms of the Bishopric of Chester, which was a more important post. There is a second plaque on the front of Bishop Lloyds House which is concerned with James I, who came to the English throne in March 1603. If the two plaques date from the same time then they must have been installed Mid 1603 to 1605 in the very first years of James' rule in England. But the problem with this interpretation is that the second plaque appears to refer to the Prince of Wales and Earl of Chester, which dates it after Henry Frederick became Prince and Earl. With his father's accession to the throne of England in 1603, Henry at once became Duke of Cornwall. In 1610 he was further invested as Prince of Wales and Earl of Chester, thus for the first time uniting the six automatic and two traditional Scottish and English titles held by heirs-apparent to the two thrones. As Henry Frederick died of typhoid on 6th November 1612 this would appear to put the plaque between his investiture in 1610 and his death in 1612. As noted above, Bishop Lloyd lived until 1615.

This article looks at the Merchant Adventures in general and in particular at their association with three instances of royal succession and their relation to the economy of Chester. These are roughly 100 years apart and are:

- The transition from Richard II to Henry IV (c 1400): the late 13th and early 14th century probably saw the peak of the city's prosperity in the Middle Ages. Henry was a usurper with a "legal" claim to the throne so weak that that it is almost ridiculous that it should be proposed. His real claim to the throne was that he gained it "by conquest", or as it might have been put "Divine Right". Chester will play a significant role in the downfall of Richard.

- The succession from Richard III to Henry VII (c 1500): for much of the period the city was far from prosperous, and occasionally, as in the 1450s, in considerable decay. The citizens claimed in 1484 that it was 'wholly destroyed' because of the silting of the harbour, and in 1486 that it was 'thoroughly ruined . . . nearly one quarter destroyed' because access for shipping had been impossible for 200 years and Welsh traders avoided it because of high tolls. By the 1490s, however, there were signs of revival and in the early 16th century Chester prospered. Chester will play an indirect role through it's association with the Stanley's, and also with Arthur Tudor the new Earl of Chester.

- The series of succession up to and including James I (c1600); Chester's economy grew steadily from 1550 to c. 1600, not least because in the early 1580s and later 1590s the passage of troops bound for Ireland created more demand for goods and services. Recovery from the plagues of 1603-5 was hampered by national economic difficulties and by recurrent, though limited, local epidemics, but from the mid 1620s prosperity returned. Bishop Lloyd and his house in Chester are involved with this.

First however, a brief look at the history of the River Dee which was so vital to the trade of Chester. As always, this is not intended to elevate Chester to an importance which it does not have, but to illustrate the general trends of history with reference to the familiar, bearing in mind that there may be unique local factors that apply. The "failure" of the port of Chester is one such factor but many other medieval ports declined and were replaced by new anchorages. Factors especially prevalent in Chester include its relative geographical isolation as regards land commerce, its history as a Palatinate/Earldom with significant elements of independence especially from Parliament, and at times the lack of a powerful local Earl.

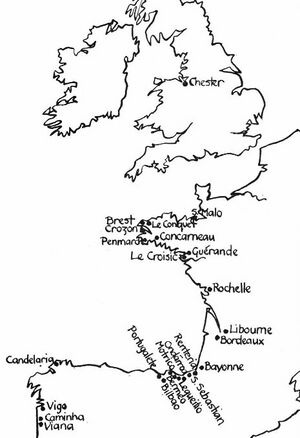

The Ruin of the River

Roman Chester, like around Caerleon and at Roman York was a Roman legionary fortress as opposed to a city. All three of these were located some distance from the sea but were connected to it by river and estuarine links. Before the advent of canals and later railways, Road Transport was restricted to routes which were often in poor condition. As they moved along these highways, travellers would meet packhorses, carts,and wagons bearing to the towns the produce of the manors or returning sometimes empty or with goods purchased in the market. Drovers might use separate routes to shift cattle and sheep. Some settlements also made use of water transport. Inland rivers and maritime routes, particularly coastal routes, were important. There was a ratio in costs per ton-mile from land transport to river transport to sea transport of roughly 8:4:1. That is, sending goods by land cost twice as much per unit weight per mile than sending it by inland waterways, and eight more times than sending it by coastal or "narrow seas" shipping. It cost more to transport wine 50 miles on land than to send it nearly 1,000 miles from Bordeaux to Chester. There are several reasons for this: costs for transporting goods over roads included feeding hungry animals; they had to be relieved of their loads each evening and reloaded in the morning; fewer men were needed on boats and per weight of cargo they were cheaper to run than a cart.

The Romans had found Chester to have an adequate natural harbour at the Roodee. This could be used to bring in wine, grain and other supplies to Roman Chester. The harbour was still important long after the Romans departed with Æthelflæd establishing the City as a "Burh"-type settlement, with a harbour and a mint. Edgar the Pacific (c943-975) was noted for bringing his fleet there and taking a boat trip on the River Dee. The city was important in resistance following the Norman Invasion. About the year 1171 Henry II granted permission to the Burgesses of Chester to buy and sell at Dublin:

- "having and observing the same customs which they observed in the time of King Henry my grandfather."

This not only suggests an earlier charter from the time of Henry I, but shows that there existed a considerable trade, even at this early period, between the two ports. The "Irish Trade" had in fact probably been continuous through the "Dark Ages", as is shown by the spread of coins minted at Chester.

Ranulf de Blondeville (Earl 1181-1232) granted:

- "to the men of Chester of my domain, and their heirs, that no one may buy or sell any kind of merchandise, which shall come to the city of Chester by sea or by land, but them or their heirs, or by their favour, save at the fairs appointed."

These fairs were appointed to be held at the Nativity of St. John the Baptist, June 24th, and the Feast of St. Michael, September 29th. The same Earl de Blondeville granted by charter:

- "to all my citizens of Chester their Gild Merchant with all the liberties and free customs which they have ever had, better and more freely and more quietly in the times of my ancestors, in the aforesaid Gild"

By the 1230s when Ranulf de Blondeville died Chester was a prosperous trading centre with a market of regional importance, two fairs, and a port. Its economy continued to expand, stimulated by royal interest and its role as a supply centre for royal enterprises in Wales, especially those of Edward I, which more than compensated the economy for the resultant temporary interruptions to the Welsh trade. The late 13th and early 14th century (Edward I and II) probably saw the peak of the city's relative prosperity in the Middle Ages.

Some relatively modern historians have also argued that the port of Chester was ruined or "manifestly decayed" by 1600. In fact Chester's trade during the 16th century was larger than ever before. In the first half of the century trade with Ireland followed a modestly rising trend while trade with both France and Spain expanded significantly to a peak in the 1530s. Following a boom in the early 1580s Chester's continental trade flagged somewhat because of the difficult conditions created by the outbreak of the Anglo-Spanish conflict in 1585. To offset this, however, the volume of goods shipped to Ireland from Chester continued to expand during the last decade or so of Elizabeth's reign.

Silting

The idea that the Port of Chester then sufferred a decline due to silting is a common one in the histories of Chester and was established as a pattern for the course of history by the first "modern historians" of Chester. Hemingway (Vol II, page 301) records the following as regards the port of Chester:

- That the Dee was navigable for vessels of great burden from the sea up to Chester in very ancient times is beyond all doubt and it is equally certain that early in the 14th century the navigation had been materially impeded by the shifting of the sands. The first notice we have of the latter circumstance is contained in letters patent of Richard II who releaseth to the citizens £73 10s 8d parcel of the £100 for the fee farm reserved by the charter of Edward I which the city was in arrears in which also is assigned as the reason of this indulgence the ruinous estate of the city and of the haven. Henry VI in confirming all the former charters of the city recites what great concourse in times past as well by strangers as others has been made with merchandise into this city by reason of the goodness of the port thereof and also what great trading for victuals into and out of Wales to the great profit of the city and then shows how the same port of Chester was lamentably decayed by reason of the abundance of sands which had choaked the creek and for these considerations released to the city £10 of the fee farm reserved by Edward I.

Frequently-cited historical records show that the people of Chester had long been compaining about the state of the River Dee. In the style of Medieval petitioners they would undoubtedly exaggerated their woes. Charters which authorised reduction in taxes in response to this must have relied of the information provided in petitions from the city. The first of these charters, after a preamble which recalls that in 1300, when the fee-farm was first granted, and that "there was a good harbour to the said city", proceeds to elaborate on the difficulties experienced in 1445:

- "And now it is so, and for forty years now last past it has been, that the great flow of water at the said port by which our said merchants had a course and return with their ships and merchandise to our said city is taken away from the harbour by the wreck of sea-sand so that the said harbour is wholly destroyed and cannot be recovered: so that no merchant ship can approach within twelve miles and more of the said city, and thus no merchant ship belongs nor has belonged to our said city, but they in default of the aforesaid harbour are wholly destroyed and wasted, to the great detriment, desolation and impoverishment of our said city and citizens."

The charter of 1486 implies an even greater disaster, now claiming two hundred years of ruin:

- "And afterwards the channel of the same port became and is at present obstructed as much by the vehement influx of sand and silting up of gravel that merchants with their ships were by no means able to reach the aforesaid city for the space of twelve miles for two hundred years now last passed, but betake themselves to other ports and places in the same country where they may more easily unload their merchandise and re-load. And the walls of the same city have fallen in decay and ruin. Besides, the aforesaid city, which of old had been wont to be inhabited fully by merchants and others rich artificers, is so thorougly ruined and prostrated to the ground that nearly one fourth part of the same city at present is destroyed and desolate."

There have been many explanations put forward as to why the port "failed". It was at times believed by many that the weir at Chester was in part responsible for reducing the tidal scour, but not all the evidence points to this historical theory of decline through river silt. Variants on this theory place the blame on fishermen using nets or incoming ships dropping ballast. However, ships were becoming larger such that they would draw more water. A case can be made out that it was not so much a decline as a failure to grow, perhaps in part due to the limitations of the river, and that major silting of the estuary only occurred after, and possibly as a result of, efforts to improve the navigation in the 18th Century. Even after these improvements one great drawback for Chester was that large vessels took two tides to reach the City from the open sea and two tides to get out. This was not a problem for shipbuilding at Chester but was a major impediment to trade.

While there are natural variations in sea levels due to the extent of polar ice, sea temperature and isostatic adjustment these may be additive or counteract each other. The average tidal volume change in the Dee is a tenth of a cubic kilometer, representing a volumetric increase of over 80% between mean low water and mean high water. Mean river discharge is nowadays comparatively small, about 0.35% of the tidal movement but may have been as high as 2% before the river was used as a source of water, so the dominant forces acting today are the tides. The transport of silt by the tides is presently "flood dominant", so tides tend to fill in the estuary. This may well be common after an "ice age", with estuaries such as the Dee actually only having a transitory lifetime of a few thousand years. Time for a port to develop, but nothing on a geological timescale.

Many other medieval ports have been destroyed by silting or erosion. Some have put this down to climate change in general or specific storms in particular. Anthropogenic causes have also been suggested: such as the aforementioned building of a weir at Chester, upland deforestation increasing the sediment load or general apathy of the inhabitants when it came to maintaining the port. The Dee estuary is also one of four areas in Britain to witness the greatest extent of land reclamation, together with the Wantsum Channel in Kent, the Fenland embayment on the southern North Sea coast, and the wetlands of the Humber Estuary. The human modifications to the Dee have caused major changes to the fortunes of ports on the estuarine bank, most notably on the English side.

Thus, the commonplace explanation that the Dee was blocked by silting is only a part of the explanation of why the extent of trade through Chester varied over the history of the port.

Customs

The Port Books and Customs Records of Chester provide insights into the details of trade, but the coverage is patchy.

Before the middle of the sixteenth century royal exchequer and chancery sources yield infrequent matter on the port of Chester and it is the financial records of the palatinate that provide details of customs collection in the port. Before 1301 financial records relating to the Earldom of Chester are meagre. and little is known about the customs taken at Chester in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. During the period of the earldom's independence from the crown (1071 - 1237) nothing has survived to illustrate the workings of the regional Exchequer of Chester. Despite the lack of evidence some customs duties were collected in the port at this time. A rudimentary form of customs organization is know to have existed in the time of Edward the Confessor. As described in the Domesday Books, in relation to laws existing in Chester, ships arriving or departing without royal licence paid a fine of 4d. to the king and earl and a duty of 4d. was taken on every "last" of merchandise shipped out of the port. The was also an early form of what was to become the "common bargain": if ships brought marten skins, the King's officers were to have first offer on them, and if this opportunity were not afforded, their owner was to forfeit fourty shillings.

- "Si sine licentia regis ad portum ciuitatis naues uenirent uel a portu recederent, de unoquoque homine qui in nauibus esset xl solidos habebant rex et comes. Si contra pacem regis et super eius prohibitionem nauis adueniret, tarn ipsam quam homines cum omnibus quae ibi erant habebant rex et comes. Si uero cum pace et licentia regis uenisset, qui in ea erant quiete uendebant quae habebant. Sed cum discederet iiii denari os de unoquoque lesth habebant rex et comes. Si habentibus martrinas pelles iuberet praepositus regis ut nulli uenderent donee sibi prius ostensas compareret, qui hoc non obseruabat xl solidis emendabat." (If a ship came against the king’s peace and in spite of his prohibition, the king and the earl had both the ship and the men and all that was in it. But if it should have come in the peace of the king and with his license, those who were on board sold what they had undisturbed. When it left, however, the king and the earl took 4 pence from each last. If the king’s reeve ordered those who had marten pelts not to sell to anyone until they had first been shown to him and he had bought, whoever neglected this paid a fine of 40 shillings.)

The areas covered by the medieval English customs jurisdictions varied over time. In the first recorded customs tax described in detail, a fifteenth assessed on overseas imports and exports from 20 July 1202 to 30 November 1204, 22 ports were noted. However Chester was not at this time part of the national customs system. Like them it had a system of "headports" and "outports". By the late fourteenth century, there were 13 customs headports: Boston, Bristol, Chichester, Exeter, Hull, Ipswich, London, Lynn, Melcombe/Weymouth, Newcastle, Sandwich, Southampton, and Yarmouth. Bridgwater was usually included in Bristol, but sometimes accounted separately. Several other ports served as temporary headports in the late fourteenth century: Cumberland/Carlisle, Liverpool, Queenborough, and Scarborough. First as an independent earldom, and then as a county palatine, Chester, in the main, lay outside the scope of the central administration throughout the Middle Ages. Its accounts, drawn up by the Chamberlain, were audited by the royal Exchequer and enrolled on the pipe rolls only during vacancies when no Chancellor was in place at Chester. After the transfer of the earldom into royal hands its financial institutions were further strengthened. The Cheshire accounts were again audited at Westminster when the king was earl, but in the years 1254-1272, when the Lord Edward held Cheshire, the county's finances were administered and audited at the Exchequer of Chester. These early exactions of duties were paid in kind rather than currency. In the year 1275/6 mention was first made of the recta prisa or the prise of wine taken on behalf of the king as earl of Chester ("one tun from afore and one abaft the mast"). After 1275 prisage of wine of denizen merchants became a regular custom exacted in the port.

The Exchequer of Chester continued working after The Crown took over the Palatinate in 1237 and From 1301 to 1554 details of prisage can be followed in the accounts of the Chamberlain of the Exchequer of Chester. Until the reign of Edward IV the Chamberlain accounted for the receipts of the prise and prisage of wine only, although yearly he rendered a nil return for the "custom of wool, woolfells and hides". This was evidently "tax avoidance" as from from 1320 onwards, the Chester Exchequer began to note that the failure to collect these customs was "since the cocket seal had not been issued". In old English law, a cocket was a custom house seal; or a certified document given to a shipper as a warrant that his goods have been duly entered and have paid duty. The seal presumably would be issued centrally. After 1301 the Chamberlain and his deputies gained full responsibilities for the collection, audit and disbursement of money. In the Middle Ages the ordinary receipts of Chester included the profits of the demesne lands; fines and amercements; fees of the seal; forest dues; and customs. The reorganisation of government finances and the creation of the new revenue courts in the 1530s stripped away some of these sources. By 1547 the Court of Augmentations had assumed full responsibility for the financial administration of crown lands, and those functions passed to the Exchequer in 1554. In 1559 customs revenues were also lost.

In the financial year 1464-65 the chamberlain, for the first time, accounted for a custom on imported iron. It was introduced without any preamble and, thereafter, became a regular Palatinate duty. In 1536 Chester was included in the general order authorizing new tariffs on exports of leather. The chamberlain of Chester did not account for this custom in the financial year 1536-37 on the grounds that the port enjoyed exemption from customs impositions under the charter of 1506. The respite was used by the citizens to petition for the suspension of the statute; but, despite the voicing of their prescriptive rights and the brandishing of their palatinate charters, they were unsuccessful. Merchants of Chester who had shipped leather contrary to the statute were pardoned but, as from the financial year 1537-38, they were obliged to pay this custom. This custom on leather was the first export from Chester to carry a palatinate duty since the exaction, in the year 1302-03, of the custom of wool, woolfells and hides.

Throughout the long period that Chester existed as a palatinate port, custuma ville, or local customs, were exacted on merchandise entering and leaving the city. The origins and early working of the local customs system at Chester are obscure because hardly any records of civic administration have survived before the fifteenth century. It is certain, however, that local customs were being taken in the port long before details of their collection have come to light. Between 1274 and 1280, when the receipts of the earldom belonged to the king as earl, the Pipe Roll accounts for Cheshire indicate that "small tolls and custom of ships and boats" comprised part of the issues of the city. In the year 1300 the citizens of Chester obtained the fee-farm of the city in perpetuity. In return for an annual payment to the earl of £100 the city received all "appurtenances, liberties and free customs" and this grant would undoubtedly have included the right to levy tolls and customs on commercial traffic in the port.

The old Custom House of the port of Chester is at 70 Watergate Street just along from Bishop Lloyds House. This custom house was built in 1633 having been relocated from within the precints of Chester Castle. It was rebuilt in 1868, possibly to the design of James Harrison, when the gothic features, which were then popular, were added. Harrison was at the time rebuildong Holy Trinity next-door to the Customs House. The building is now a restaurant. Up to 1671 Liverpool was a member-port or "creek" of the head-port Chester. While the outports of the customs office at Chester have varied over time, they reached along an extensive western coastline of England and Wales. Little is now known of how customs records from these outports were handled, so figures derived from them need to be treated with caution.

Thus, the Customs and Port Book evidence can be used to look at the details of trade, but as this brief survey shows there were frequent changes to the system and the practices during any part of the lifetime of the port should not be taken as indicative of the practices during the whole of the time that the port prospered.

Contrary Evidence

As noted above, the charters which mention silting of the Dee also need to be read with caution as the citizens are medieval petitioners and exaggeration was customary. There is every reason to think that, despite silting, the small craft which plied the Dee in the later Middle Ages could have reached the Portpool and perhaps the Watergate. This certainly seems true as shown in the Braun and Hogenberg map of 1581 some hundred years later. Despite the claims of depopulation as a result of silting - "many citizens and other inhabitants of our said city are withdrawing themselves from our said city" admissions into the franchise at Chester did not show any drastic reductions in the 15th century.

The right to establish anchorages far beyond the limits of the city liberties was an aspect of Chester's control of the whole of the Dee estuary. The citizens' rights were first specified in the charter of 1354, which allowed them to levy tolls and other customs and to make attachments for offences committed in the water of Dee between the city and Arnold's Eye, at Hilbre Point, the extremity of the estuary. The grant, which is generally taken to be the origin of the mayor's powers as 'admiral' of the Dee, claimed to continue ancient custom. The citizens' privileges were clarified in 1506: they were to have the 'searching' of the Dee from Heronbridge to Arnold's Eye, oversight of nets, weirs, and fishing, and the collection of fines from all transgressions. Anchorages were established further down the Dee, at Shotwick, Burton, Denhall (in Ness), Neston, Gayton, Heswall, 'Redbank' (later Dawpool) in Thurstaston, and at Point of Ayr (in Llanasa, Flints.). In the 14th and 15th centuries "Redbank" was much the most important, but Burton and Denhall rose to significance in the early 16th century. Those closest to the city, Portpool and Shotwick, were affected by silting; they were disused from the later Middle Ages, and a quay established at Shotwick in 1449 proved of little value. The fluctuations in the fortunes of the others reflected a succession of shifts in the river's course rather than progressive silting downstream.

The charters also need to be seen in the light of the economic conditions of the time, which could well have given rise to pleading of a special case. The period 1399-1485 saw the Wars of the Roses, but that consisted of intermittent campaigns which not appear to have caused large-scale devastation, although as an internal war it could not produce growth through conquest or plunder. Compared with the economic boom that occurred in 12th century England, the later economic situation was in general very bleak in the mid-fifteenth century. Historians now refer to the mid-fifteenth century as "The Great Slump" but the thirty years preceding the accession of Henry VII in 1485 were not years of continuous and all-consuming destructive anarchy. It was more a series of plots, murders, uprisings, rebellions, invasions and battles, most intense in 1459-64, 1469-71 and 1483-7.

Chester was not so dependent on the wool trade as elsewhere, and English woollen cloth exports had collapsed by a third between 1440 and 1450. Henry VI’s Government did not help when it got itself into a trade war with Burgundy: this had led to Burgundy banning the import of English woollen cloth. Several reasons have been advanced for the economic downturn of the Great Slump. It has been suggested that there was a shortage of coin, possibly caused by a continent-wide scarcity of silver that became most severe in the 1400s. This apparent lack of liquidity has been much debated, with suggestions that the shortage was caused by trade deficits with the East and declining production of precious metals. Whereas in the 1350s, it has been estimated that there were 56 pennies in circulation per capita, by the 1420s, there was just 13 pennies available per head of the English population. In practice, as with the "deline" of trade on the River Dee there would have been many contributory factors.

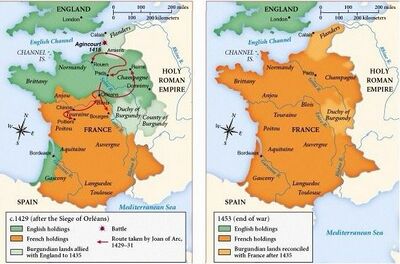

The so-called "Lancastian Phase" of the Hundred Years War lasted from 1415-1453. Initial English successes, notably at the Battle of Agincourt (1415), coupled with divisions among the French ruling class, allowed the English to gain control of large parts of France. French forces counterattacked, inspired by Joan of Arc, La Hire and the Count of Dunois, and aided by the English loss of its main allies, the Dukes of Burgundy and Brittany. Charles VII of France was crowned in Notre-Dame de Reims in 1429, and from then a slow but steady reconquest of English-held French territories ensued. These gain and loss of foreign ports by the English as well as the difficulties of trade in times of war would have also effected the fortunes of the port of Chester.

The Port Books also show us the type of goods passing through Chester. As well as hides, cloth and iron, there was a considerable trade in wine.

Wine

Gascony was the source of much of the "French" wine that arrived in Chester. After 1152 and before the Battle of Castillon on 17 July 1453 it had frequently been in English hands as part of Aquitaine. The wealth of Gascony derived largely from its production of non-sweet wine. By the early part of the 14th century, an average of 80,000 tuns of wine a year were exported from Bordeaux, about a quarter of it to England. In 1308-09 a record 102,724 tuns passed through the Gironde estuary. Although it lasted for the better part of England’s 300-year rule of the Duchy of Gascony and wine imports were one of the leading sources of revenue for the English crown, it nonetheless faced constant obstacles stemming from the various political, economic and social crises of the era. Even before the outbreak of the Hundred Years War, Gascony had been invaded by the French in 1294 and 1324. Then, from 1338 to 1453, the duchy would suffer repeated incursions and devastating raids known as "chevauchées" by 1400 the lands under English control had been reduced by French incursions in the 1370s to the region south of Saintonge and Périgord concentrated around the Gironde estuary and the capital city of Bordeaux.

In 1445 for example, as far as wine imports were concerned, Chester was in the middle of its least prosperous decade since the beginning of the fifteenth century. Estimated decennial totals were in the region of 1,000 tuns in 1400-10. They climbed to over 2,000 tuns in 1410-20 (more than in any decade between 1350 and 1510), fell back to just over 1,000 tuns in 1420-30 and 1430-40, but in the decade 1440-50 dropped to 800 tuns. Prices varied between ports but were probably about 1s/4d a gallon in 1429. The tun (Old English: tunne, Latin: tunellus, Medieval Latin: tunna) is an English unit of liquid volume (not weight), used for measuring wine, oil or honey. Just how large a tun was could be debated: the standard wine tun of Bordeaux (generally estimated at c 252 gallons capacity) became the recognised measurement of the capacity or size of a ship. In modern terms a tun of wine would be c.1500 bottles. This works out at sixpence a bottle - a days wages for a cooper. Gascony, an English possession from which much wine was shipped, was lost under Henry VI in 1453, at the end of the Lancastrian Phase of the Wars of the Roses.

In the 1480s the wine trade at Chester was still depressed and, even more telling, between 1460 and 1490 the bulk of wine imports into Chester were freighted by non-freemen. The expansion of shipping by foreign traders is visible at Chester as only the occasional Spanish ship or shipper importing wine or iron is recorded between 1464 and 1474, then from 1484 it became increasingly common for two, or three, or four Spanish ships to unload iron there. The Irish and coastal trade, which ranked as the port's major commercial activity, does not appear to have suffered to the same degree as the overseas trade. Irish and coastal shipping arriving in the port in the fifteenth century did not show any appreciable decline until after 1460, and from the mid-1470s arrivals reached their pre-1460 levels. These are only the official figures and do not account for any customs avoidance. Apart from a few specific productss, the records do not permit statistical analysis or quantification of Chester's trade in the late 14th and 15th century. All that can safely be said is that an average of 49 ships arriving each year in the 1420s dropped to 40 in the 1450s, 35 in the 1460s, and 30 in the 1470s, but then apparently rose to 44 in the 1490s. The busiest single year was 1500-1, with 57 ships. Such totals were small in comparison with major ports on the east and south coasts, and included tiny boats with only one or two crewmen. Chester's overseas trade probably declined after the 1420s, reached its nadir in the 1470s, and began to improve in the 1490s, a recovery which ran counter to the citizens' claims about silting having already destroyed the river by the time of Richard II.

To summarise:

- Maritime and riverine trade played a large part in the pre-canal economy of Chester;

- Chester was a significant port and largely independent of the national customs system;

- The surviving Customs Records for Chester are a very useful historical source;

- Wine, iron and hides/leather were the subject of early customs charges taken at Chester;

- In the year 1300 the citizens of Chester obtained the fee-farm of the city in perpetuity, in return for a fixed fee;

- Chester retained its independence from the national customs system until the 16th century;

- The River Dee was not "destroyed" simply by silting from upriver or the construction of the weir. It was the movement of the channel which opened and closed the outports in the estuary.;

- External economic factors played a large part in the variance of trade;

The next section of this article looks at the first of the political transitions being considered. That of Richard II's ursupation by Henry Bollingbroke who then became Henry IV in 1399.

Richard II (for more on him see: Royal Treasure)

The transition from Richard II to Henry IV (c 1400): the late 13th and early 14th century probably saw the peak of the city's prosperity in the Middle Ages. Henry was a usurper with a "legal" claim to the throne so weak that that it is almost ridiculous that it should be proposed. His real claim to the throne was that he gained it "by conquest", or as it might have been put "Divine Right". Chester will play a significant role in the downfall of Richard.

Richard II (r. 1377-99) was born to Edward, the Black Prince and his wife Joan, Countess of Kent on 6th January 1367, in Aquitaine, then under English control. He was their youngest son, and he had one older brother who was also called Edward. From his early life, Richard was a spoiled child; he even had a set of dice loaded so that he always won. Richard was crowned on 16th July 1377 at Westminster Abbey. One of his first initiatives as king (or rather, one of the first initiatives from his advisors) was to introduce a poll tax. England was still recovering from the economic impact of the Black Death, and the crown’s resources were running low as was the same elsewhere. In 1345, for example, Edward III defaulted on his debt, as a consequence the Florentine banks Bardi and Perruzi both went bankrupt. Not only was the Crown hard-up, but the labour shortages following the Black Death were bringing about enormous economic change. The economic policies of the time are not well understood, but it is possible to draw a rough and much debated picture of the potential polarities: Edward III wished to produce plenty and large cargoes whoever brought them, while the Ricardian Parliament wanted more English ships (even if the home consumers were for a time badly supplied with wine).

Unlike his father (Edward the Black Prince) or grandfather (Edward III), Richard II was not particularly warlike especially when it came to continental conquest and plunder. He became king at an early age (1377, aged ten years) and thus spent little time as Earl of Chester, having only been made Prince of Wales in 1376 upon the death of his father. As a consequence he did not use the holdings of the Earldom of Cheshire to finance wars. In 1351, as part of a more general investigation of his earldom's franchises, the Black Prince had instituted quo warranto proceedings in Chester. For a ratification of their charters and a declaration of the bounds of their liberties, the citizens agreed to a fine of £300, which because they were impoverished was to be paid by instalments over five years. Royal officials delayed the matter until the prince himself went to Chester in 1353. His visit, which lasted some two months, involved a meeting in the city at which the men of the shire paid a fine of 5,000 marks to maintain their franchises. Chester in 1354 obtained a charter defining the boundaries of the liberty, confirming its admiralty powers over the Dee, and further excluding royal officials by annexing its escheatorship to the mayoralty. Once again this came at a price, although the payments promised in return for those privileges were extracted by the prince only with considerable difficulty. The Black Prince again visited Chester briefly in 1358, but is not known otherwise to have gone there. The links of his son, Richard II (ruled 1377-99), with the city and shire developed only in the later years of his reign.

Richard II visited Chester for the first time in 1387 and granted the citizens a murage for the repair of their ruined bridge. His favourite, Robert de Vere, earl of Oxford, whom he made justice of Chester, established his household in the city and while based there raised the army which was defeated at Radcot Bridge later in 1387. The battle was part of the more general conflict between Richard and the "Lords Appellant" who (according to some) wanted to curb Richard's increasingly capricious and tyrannical behaviour, and (according to others) promote their own interests, including war with France. The failure of de Vere's campaign was celebrated locally by his enemy Richard FitzAlan, earl of Arundel, who from his base at Holt Castle caused a copy of the appeal against the royal favourite to be nailed to the door of St Peter's church. As a part of the crisis, all English Ports were sealed, and all writs of passage collected on 14th January 1388. This may well have been a temporary measure intended to prevent the escape of Richard's supporters.

On 3 May 1389, claiming that the difficulties of the past years had been due solely to bad councillors. Richard outlined a foreign policy that reversed the actions of the appellants by seeking peace and reconciliation with France, and promised to lessen the burden of taxation on the people significantly. Richard ruled peacefully for the next eight years, having reconciled with his former adversaries. In 1396 Richard married the French princess Isabella, who at the time was six years old. This was a political union to cement the Truce of Leulinghem with Charles VI of France. Unfortunately for Richard, Charles VI was mentally unstable and the political situation in France was volatile. Howver, French foreign policy shifted in the years following the truce, and the focus was placed on Italy as the French attempted to gain a foothold whereby they could force the Roman pope to abdicate. Genoa became a French protectorate. Charles's mental state continued to deteriorate, leading to more fighting in the court, with his wife allying with his uncles in opposition of Charles's brother, Louis of Orleans, Duke of Touraine. The truce was always fragile. When Henry IV took the throne in England, the French initially interpreted it as a repudiation of the truce and raised an army and strengthened their garrisons on their borders. An embassy to England reconfirmed the truce with Henry.

In 1397, Richard II created the title "Prince of Cheshire", which he awarded to himself. On 13 July 1397, he ordered the sheriff of the county of Chester to collect 2,000 archers for royal service. These troops were used to overawe the parliament which met in September - sometimes known as the "Revenge Partiament". Most were then allowed to return home, but the king kept back others to form his personal bodyguard, receiving wages of 6d per day, which was the standard rate for archers in royal armies in the late fourteenth century. This wage was on a par with that of a skilled craftsman. This personal bodyguard was made up of Cheshire bowmen who were described as being intolerably arrogant, insolent ruffians who lived on far too intimate terms with king. By the autumn of 1398, Richard had a bodyguard of over 300 Cheshire archers which was grouped into seven "watches", four containing 44 archers, two with 45 archers, and one with 46 archers. That there were seven groups suggests that each may have been responsible for the watch on one day of the week. Each watch was under the command of a knight or esquire from Cheshire: John del Legh del Boothes; Richard de Cholmondeley of Cholmondeley; Ralph de Davenport; Adam de Bostok; John Donne of Utkinton; Thomas de Beeston; and Thomas de Holford. In 1389, after the king had reasserted his personal authority, the men of the shire met at Chester and granted a subsidy of 3,000 marks for their losses at Radcot Bridge.

Richard II’s court was a high-tax, high-spend affair. It was reported that on a 1396 trip to France, he spent £150,000 on clothes for his wardrobe. In 1399 Richard II had a heated bathroom constructed in Chester Castle (costing £70). It was paneled with Norwegian timber. His apartments were redecorated with cushions and fine silk hangings, but he would not enjoy it for long. The truth of Richard's style of goverment may have had some bearing on other "improvements" at Chester Castle: Thomas le Wodeward, deputy constable of the castle, took delivery of the following new supplies in 1397: 11 iron collars and 2 gross of iron chain; 2 pairs of iron belts with shackles; 2 pairs of iron handcuffs with 4 iron shackles; 7 pairs of iron feet fetters with 3 shackles; 1 hasp for the stocks.

In 1399 Richard was invading Ireland when Henry Bolingbroke landed with his troops. Henry beat Richard to Chester. The Duke of Lancaster made his way to Chester by somewhat sporadic forced marches and took it without a fight on the 9th August. The Duke stayed at Chester Castle for 12 days, amusing himself by drinking the king's wine, wasting fields and pillaging houses. and presumably enjoying the use of Richard II's "Norwegian Wood" heated bathroom. While there ("this thief, this traitor, Bolingbroke, who all this while hath revell'd in the night": Rich II 3:2 line 46ff), he also found time to secure the arrest, incarceration in the Gowestower (outer gatehouse tower) and execution of Sir Peirs Legh of Lyme, one of Richard's leading retainers in Cheshire and the brother of the Sheriff - Legh's head was placed on the Eastgate. Richard arrived at Conwy to find himself hemmed in. Salisbury's levies had already dispersed, possibly following a rumour that the King was dead. Defections on the road had reduced his own small following to six if we believe later chronicles (Traïson, pp. 282, 293).

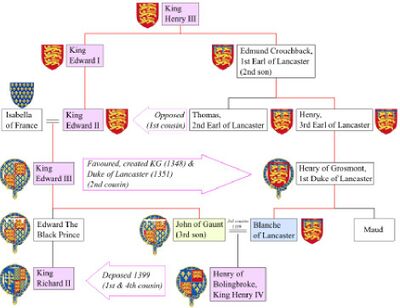

The Sons of Edward III

The English Monarchy is known for some interesting successions, and a few monarchs stand out as being those from whom a valid bloodline can be argued. The failure of such bloodlines has often lead to a succession "crisis". Notable examples among many are the failure of the Norman line (leading to "The Anarchy") and the new start with Henry III, the ursupation of Richard II and that of Richard III, and the transition between the Tudors and the Stewarts on the ascention of James VI/I. The Lancaster and York branches of the monarchy started from the third and fourth sons of Edward III. These were: Duke of Lancaster John of Gaunt and Duke of York Edmund of Langley. The family tree is based on the order of Edward III’s children, the Lancaster branch would therefore be considered senior to the York branch. Richard II, came to the throne because he was the son of Edward III’s eldest so: his father, Edward the Black Prince died before Edward III did, so through primogeniture down the Plantagenet line Richard II became heir.

Henry of Bolingbroke, son of John of Gaunt (Lancaster), usurped Richard II. Bollingbroke became Henry IV but his problem was he had a very shaky clain to the throne: he claimed the throne as the right heir to King Henry III by asserting that:

- Edmund Crouchback was the elder and not the younger son of King Henry III, i.e. that he was born before Edward I, but passed over due to a deformity;

- every monarch from Edward I onwards was a usurper, and;

- his mother Blanche of Lancaster was a great-granddaughter of Edmund Crouchback.

There is nothing to suggest that Edmund Crouchback was actually deformed, or that he was the eldest son of Henry III (that was Edward I). Edmund accompanied his elder brother Edward on his crusade in the Holy Land, where his epithet, "Crouchback," originated from a corruption of "cross back", referring to him wearing a stitched cross on his garments. There is also nothing to back-up the argument that every monarch from Edward I onwards was a usurper, as these include Edward II and III as well as Richard II who died without issue. It was a truly rubbish argument for a valid claim.

Unfortunately Edward III had a further son and his descendant was the heir of the royal estate according to common law. He was the very young Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March, who descended from the daughter of Edward III’s third son (second to survive to adulthood), Lionel of Antwerp. Lionel's daugher was Philippa, 5th Countess of Ulster, the mother of Roger Mortimer, who was in turn the father of Edmund. Bolingbroke has to surpress a many plots and revolts through his reign, but fortunately Ednund Mortimer, who was aged seven when Richard was deposed, remained loyal, especially to Henry V. The Mortimer claims were later inherited by the House of York, which claimed the throne upon the Earl of March Edward IV's victory in the Battle of Towton, 1461.

Economic Effects

One minor economic consequence of Richard II was the remarkable number of inns which displayed his personal symbol the White Hart. In 1393, during the reign of King Richard II, an Act was passed which made it compulsory for pubs and inns to have a sign in order to identify them as official watering holes and many chose the king's badge. It is still high in the ranking of pub names along with the Red Lion, Crown and Royal Oak (due to Charles II). The Red Lion as a pub sign probably has multiple origins: in the arms or crest of a local landowner, now perhaps forgotten; as a personal badge of John of Gaunt, founder of the House of Lancaster; or in the royal arms of Scotland, conjoined to the arms of England after the Stuart succession of James I in 1603. It is perhaps surprising that there is no noted White Hart in Chester: one was trading in Foregate Street in 1781, and there was another White Hart in Northgate Street, but neither is particularly notable.

Very little can be said of the economic consequences in Chester of the transition from Richard II to Henry IV. The decline in the wine trade during the 14th Century could be associated with general impoverishment or with the French wars. The overall trade as represented by the total number of ships follows a similar pattern. The recovery in the 1490's may be a consequence of peace with France. Although the city's outports were busy, the volume of goods carried into the city and their final destination are unknown. A county regularly skimmed by its royal earls for cash to maintain English garrisons in Wales, and routinely exploited by the earls' numerous lessees for short-term profit, may have represented a limited market for imported goods.

Cheshire's peculiar status was that of a Palatinate under direct royal rule (in the person of Prince of wales) and not, therefore, subject to the regular system of local government in operation throughout most of the country. This certainly tended to give scope for disorder if royal control were not firmly exercised, especially at times of dynastic change. The ursupation of Richard II led to an increase in the disorder with local revolts culminating in the Battle of Shrewsbury. In June 1403 the sale of grain and other provisions to Welshmen in Flintshire and elsewhere was prohibited, as it was alleged that this produce was later sold to the rebels. According to tradition, for which little firm evidence can be found, trade with the Welsh was the origin of a supposed law which allowed the authorities to "Shoot the Welsh".

One of the problems faced by Henry IV was piracy by his own subjects on the ships of friendly nations. This would also have consequences for Chester. A pirate war raged in the Channel as English corsairs attacked friend and foe alike. It was around this time that the maritime trade saw the development of the square rig cog. It allowed a combination of square sail, and the Lateen, triangular sail – which was deployed usually on the mizzen mast with the sail aft. The Lateen sail allowed ships to tack much closer to the wind, it was much easier to manoeuvre ships in difficult or restricted conditions. Fore and stern castles would be added for defense against pirates. The stern castle also afforded more cargo space below by keeping the crew and tiller up, out of the way and the flat bottom allowed them to settle on a level in harbour or other anchorage, making them easier to load and unload. The rigging allowed the number of sailors to be reduced. Around the 14th century, the cog reached its structural limits, and larger or more seaworthy vessels needed to be of a different type. This was the hulk, which already existed but was much less common than the cog. Eventually the hulk was replaced by the Caravel and then the Carrack.

With Spain the treaty concessions and period of peace under Edward IV and Richard III brought increased trade, helping to produce the downward drift of prices, and annual imports of Spanish iron rose to well over 2,500 and probably well over 3,000 tons. Bristol alone in 1492-3 imported over 648 tons of Spanish iron, but the highest amounts are recorded in London; there Spanish merchants alone imported 2,099 tons in 1487-8, 2,532 tons in 1490-1, and 1,614 tons in 1494-5. At this time too imports of Spanish iron to the smaller western ports, now including Chester, were rising sometimes to 100 tons a year.

The next section of this artcle jumps forward to the Stanley's who played a major part in the next ursupation, that of Richard III by Henry Tudor. Henry Tudor plays a key part in the final transition as reflected by the carvings on Bishop Lloyds House, as Henry was the common ancestor of the all the possible rival claimants to James I. As we shall see the many of the same types of issues arose in attempting to justify the successions of Henry IV, Henry VII and James VI/I.

To touch briefly on the intervening years, following the Treaty of London in 1474, Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, had agreed to aid England with an invasion of France. By June 1475, Edward IV had landed on the coast of France. Edward IV had an army of around 11,000 and a further 2,000 archers from Brittany. Edward's plan was to march through Burgundian territory to Reims. However Charles failed to provide the support he had promised, and refused to allow the English to enter Burgundian-controlled towns. Edward also received little support from his other ally Francis II, Duke of Brittany. Louis XI then sent Edward word that he was willing to offer more than Edward's allies could. He contacted and induced Edward to negotiate a settlement. The two negotiated by meeting on a specially-made bridge with a wooden grill-barrier between the sides, at Picquigny, just outside Amiens. The resulting treaty formally ended the Hundred Years' War. Although the Treaty of Picquigny in 1475 allowed greater freedom of trade, numbers remained low until the late 1480s, when Spanish ships began to arrive, bringing wine, iron, and oil, and returning to their home ports in the bay of Biscay with calfskins, tallow, and coloured woollen cloth. King Richard III’s reign (26 June 1483 – 22 August 1485) came at a major turning point in English economic history: from the 1440s until the 1470s, England had been gripped by a severe economic depression, a function not of civil conflict or strife by rather the result of high epidemic mortality as a consequence of the Black Death (1348 - early 1350's), and a contraction in international trade.

To summarise:

- Richard II made the Eardom of Chester a principality with himself as prince;

- Richard's peace with France led to a pause in the Hundred Years' War and an increase of trade;

- Richard's association with Chester was co-incident with a recovery of trade in Chester;

- Henry Bolingbroke has a very poor claim to the throne by ancestry;

A Stanley Succession

During the series of succession up to and including James I (c1600), Chester's economy grew steadily from 1550 to c. 1600, not least because in the early 1580s and later 1590s the passage of troops bound for Ireland created more demand for goods and services. Recovery from the plagues of 1603-5 was hampered by national economic difficulties and by recurrent, though limited, local epidemics, but from the mid 1620s prosperity returned. Bishop Lloyd and "his" house in Chester are involved with this as are the Stanley's.

The Earls of Derby were among the most influential and prominent noble families in England, and especially in the North. The title was first adopted by Robert de Ferrers, 1st Earl of Derby, under a creation of 1139. The fourth Earl, William de Ferrers even manged to combine the title with Earl of Chester after the death of John Canmore. It continued with the Ferrers family until the 6th Earl, Robert de Ferrers, forfeited his property toward the end of the reign of Henry III and died in 1279. Most of the Ferrers property and (by a creation in 1337) the Derby title were then held by the family of Henry III and it appears that the future Henry IV held the title prior to becoming elevated to the Dukedom of Hereford. The 1337 creation was that of Edmund Crouchback's grandson, Henry of Grosmont (c.1310–1361), afterwards Duke of Lancaster, was created Earl of Derby, and this title was taken by Edward III's son, John of Gaunt, who had married Henry's daughter, Blanche. John of Gaunt's son and successor was Henry Bolingbroke. The title merged in the Crown upon Henry IV's accession to the throne in 1399. The title was created again, this time for the Stanley family, in 1485 after the Battle of Bosworth Field where Thomas Stanley decided to betray King Richard III.

While the ones mentioned in this article did not live in Stanley Palace the building is still worth a visit. Ferdinando Stanley was a great-grandson of Mary Tudor, the younger sister of King Henry VIII. As explained below this made him an heir to the throne. Ferdinando was the brother to the William Stanley who presented George Lloyd as the Bishop of Sodor and Man. For many years it was thought that the arms of the Stanley's also featured on Bishop Lloyds house, being placed together with the Bishop's arms in one of the panels. Recent (2023) drone investigation has shown that the blazon displayed is not that of the Stanley's but features three fleur-de-lys and not three stag's heads. This couls be an error (like the reversed "Legs of Man"), but the Stanley arms would be very well known in Chester. The Stanley's had been Kings of Mann since 1405 when Henry IV granted the suzerainty of the Isle of Man, to Sir John Stanley.

The Stanleys had risen to prominence at the same time the Wirral had been disafforested and were involved in a considerable ammount of associated feuding and violence. John Stanley was very agile in his politics. Having served Richard II as deputy to Robert de Vere, Duke of Ireland (and possibly Richard's lover), he turned his back on Richard and submitted to Henry IV, the first English king of the House of Lancaster. Stanley's fortunes were equally good under the Lancastrians. He was granted lordships in the Welsh Marches, and served a term as Lieutenant of Ireland. In 1403 he was made Steward of the Household of Henry, Prince of Wales, (later Henry V). Unlike many of the Cheshire gentry, he took the side of the king in the rebellion of the Percys. He was wounded in the throat at the Battle of Shrewsbury. In 1405 he was, as noted, granted the tenure of the Isle of Man. Henry IV appointed him a Knight of the Garter. His descendants were to prove equally agile, shifting sides deftly through the Wars of the Roses and after.

In addition, but separate from the power of governance over the Island, John Stanley (back in 1405) was also granted the patronage of the Diocese of Sodor and Man, which passed down to William Stanley the 6th Earl of Derby who presented Lloyd as Bishop in late 1600. William Stanley would eventually retire to Chester (see: Shakespeare and Chester): a few years after the death of his wife (she died in 1627), when Derby was "old and infirm, and desirous of withdrawing himself from the hurry and fatigue of life" he assigned his estates to his son James, retaining an annuity of £1,000. He bought a house by the River Dee just outside the Walls of Chester, where he lived in retirement until his death on 29 September 1642.

The Succession

Parliament's Third Succession Act granted Henry VIII the right to bequeath the crown in his Will. His Will specified that, in default of heirs to his children, the throne was to pass to the children of the daughters of his younger sister Mary Tudor, Queen of France. In doing so, he excluded the kings of Scotland, descendants of his elder sister Margaret Tudor, represented by the Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots. Edward VI confirmed this by letters patent in his "Devise for the succession" in which he undertook to change the succession, most probably inspired by his father Henry VIII's precedent. He passed over the claims of his half-sisters and, at last, settled the Crown on his first cousin once removed, the 16-year-old Lady Jane Grey. The letters patent were issued on 21 June and signed by 102 notables, among them the whole Privy Council, peers, bishops, judges, and London aldermen as well as by the Merchants of the staple (six), and Merchant Adventurers (six). The only surviving text of the Devise is that from the transcript of Ralph Starkey in the MS. Harl. 35, f. 364, which is preceded by this title:

- "A true coppi of the counterfet wille supposed to be the laste wille and testament of kinge Edwarde the Sixt, forged and published under the Great Seale of Englande by the confederacie of the dukes of Suffolke and Northumberlande, on the behalfe of the Lady Jane, eldest daughter to the said duke of Suffolke, and testefied with the handes of 101 of the cheife of the nobilliti and princepall men of note of this kingdome; dated the 21 day of June an[n]o. 1553;"

and followed by this memorandum:

- "This is a true coppie of Edward the Sixte his will, taken out of the original under the Greate Seale, which sir Robart Cotton delyvered to the kinges majestie the xijth of Apprill 1611, at Roystorne, to be canseled."

Both Mary and Elizabeth had been named illegitimate during the reign of Henry VIII after his marriages to Catherine of Aragon (Mary I's mother) and Anne Boleyn (Elizabeth I's mother) had been declared void. The second act of succession (1536) removed them from the line of inhritance. Unfortunately, Jane only ruled for nine days. On 19 July 1553, Jane was imprisoned in the Tower's Gentleman Gaoler's apartments, her husband in the Beauchamp Tower. Her chief supporter the The Duke of Northumberland was executed on 22 August 1553. In September, Parliament declared Mary the rightful successor and denounced and revoked Jane's proclamation as that of a usurper. In doing this they were following the Law as the "Devise for succession" could not overrule an act of parliament, and there had been no time to put such an Act through. Had Edward lived long enough to secure a parliamentary warrant for his letters patent and impose a corresponding Oath of Succession, or had Northumberland and the Council managed to gain custody of Mary and more effectively coordinated the military and public relations side of the coup, or had Mary shown less stamina, Jane might have held on to the throne. She and her allies would have probably sought parliamentary recognition of her title, just like her great-grandfather and founder of the Tudor dynasty Henry VII had done half a century earlier,

On 12 February 1554 Jane Grey was executed. During the Marian persecutions and its aftermath, Jane became viewed as a Protestant martyr, featuring prominently in the several editions of Foxe's Book of Martyrs (1563 - more properly "Actes and Monuments of these Latter and Perillous Dayes").

Jane Gray's Sisters

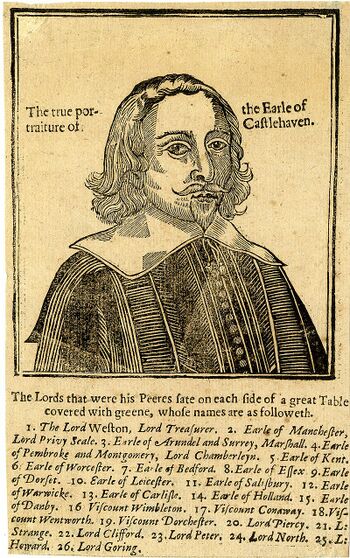

Elizabeth succeeded Mary upon the death of the latter in November 1558. Jane Grey had been married to Lord Guildford Dudley (c. 1535 – 12 February 1554) and had no children. Lady Katherine Grey (25 August 1540 – 26 January 1568) was a younger sister of Lady Jane Grey. A granddaughter of Henry VIII's sister Mary, she emerged as a prospective successor to her cousin, Elizabeth I of England, before incurring Queen Elizabeth's wrath by, in December 1560, secretly marrying Edward Seymour, 1st Earl of Hertford. Arrested after the Queen was informed of their clandestine marriage, Katherine (as Lady Hertford) lived in captivity until her death, having borne two sons in the Tower of London. In 1562, the marriage was annulled and the Seymours were censured as fornicators for "carnal copulation" by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Matthew Parker. This rendered their children illegitimate and thereby ineligible as successors to the throne. The children included Edward Seymour (21 September 1561 – July 1612), Lord Beauchamp.

A further sister of Jane Grey, Lady Mary Grey, also married without the Queen's permission. On 16 July 1565, while the Queen was absent attending the marriage of her kinsman, Sir Henry Knollys (d. 21 December 1582), and Margaret Cave, the daughter of Sir Ambrose Cave, Mary secretly married the Queen's sergeant porter, Thomas Keyes. Upon hearing that the wedding had taken place, the Queen is said to have declared wrathfully that "I'll have no little bastard Keyes laying claim to my throne". Keyes was committed to solitary confinement in the Fleet prison, while Lady Mary was placed under strict house arrest. The two would have no children.

The sanctions taken were intended to cut out any possible bloodline through the Greys. The only valid succession was apparently through the sister of the mother of the Gray sisters, Eleanor Clifford, Countess of Cumberland. This led to the Stanley's.

The Stanley Claim

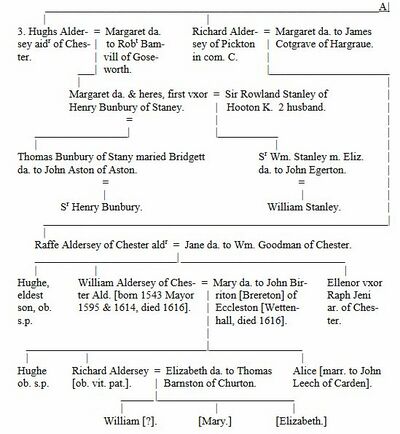

Elizabeth's heir was now Margaret Stanley (née Lady Margaret Clifford; 1540 – 28 September 1596). She was the only surviving daughter of Henry Clifford, 2nd Earl of Cumberland and Lady Eleanor Brandon. Her maternal grandparents were Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk and Mary Tudor, Queen of France. Mary was the third daughter of King Henry VII of England and Elizabeth of York. In 1579, Margaret was arrested after she had been heard discussing a proposed marriage of Queen Elizabeth to the Duke d'Alençon. She was opposed to it as it threatened her own possible accession to the crown. She was then accused of using sorcery to predict when Elizabeth would die, and even of planning to poison Elizabeth. Simply predicting the death of a monarch was a capital offence at the time. The countess was put under house arrest. She would die in 1596. However she had married Henry Stanley, 4th Earl of Derby on 7 February 1555 in the Chapel Royal at Whitehall Palace, with whom she had four children: Edward Stanley (who died young); Ferdinando Stanley, 5th Earl of Derby; William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby (c. 1561 – 29 September 1642) and Francis Stanley (b. 1562, died young).

Elizabeth I balked at establishing the order of succession in any form, presumably because she feared for her own life once a successor was named. By 1580, it was obvious that Queen Elizabeth I would have no children, and this focused attention on Ferdinando Stanley as a possible future king. After the likely murder of Ferdinando (16 April 1594), the legitimate and legal heir of Elizabeth I, following the will of Henry VIII was therefore his eldest daughter Anne Stanley, Countess of Castlehaven. Descent from the two daughters of Henry VII who reached adulthood, Margaret and Mary, was the first and main issue in the succession. Ferdinando had two further daughters, of which Frances married Sir John Egerton, son and heir of Thomas Egerton, Lord Elsmere, then Lord Chancellor of England; and Elizabeth, the youngest, after married to Henry Hastings, Earl of Huntingdon. To complicate matterss further after Ferdinando Stanley's death, his widoww Lady Alice had married John's father Thomas Egerton. The Dowager Countess of Derby and her three daughters had access to an extensive network of highly influential people, including the royal court. The Dowager Countess and her daughter Elizabeth, Countess of Huntingdon, were politically active and promoted the interests of their family through that network. All four Stanley women were interested in drama and poetry, and supported theatre groups, writers and poets, including Edmund Spenser, John Donne and John Milton.

In 1598, a succession dispute between the daughters of Ferdinando and their uncle, William, Earl of Derby, was heard by the Privy Council. They eventually (in 1607) decided that the right to the Isle of Man had belonged solely to Queen Elizabeth I, and the letters patent of 1405 which conferred the lordship of the Isle of Man on the Stanley family were declared null and void as the previous ruler, Henry, Earl of Northumberland, had not been subject to legal attainder, despite his treason, and the 1405 and 1406 letters patent had therefore not taken effect.

Bishop Lloyd and Royal Genealogy

The future James I was the only son of Mary, Queen of Scots, and her second husband, Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley. Both Mary and Darnley were great-grandchildren of Henry VII of England through Margaret Tudor, the older sister of Henry VIII. From 1601, in the last years of Elizabeth's life, certain English politicians — notably her chief minister Robert Cecil — maintained a secret correspondence with James to prepare in advance for a smooth succession. With the queen clearly dying, Cecil sent James a draft proclamation of his accession to the English throne in March 1603. Elizabeth died in the early hours of 24 March, and James was proclaimed king in London later the same day. While the accession of James went smoothly, the succession had been the subject of much debate for decades, especially given that it was in direct contravention to the Will of Henry VIII.

In June 1604 Lloyd was in London and working on an assignment to revise any crude mistakes in the catalogue of British chronology in which the Royal family’s genealogy has been inserted. The Stuarts wanted a clear lineage to be shown reaching back to Henry VII, as well as Edmund Tudor and his wife Margaret Beaufort. It is through Margaret that the disputed claim to the throne passed to her son Henry Tudor later Henry VII, Elizabeth and Mary Queen of Scot's common ancestor. There were apparently no other claimants who were not descended from Henry VII. The documents Lloyd was working with may have included the "Biblical and genealogical chronicle from Adam and Eve to Edward VI (the Longer English genealogical chronicle of the kings of England)" (Kings 395 in the British Museum). The text of the chronicle ends with Richard III. The pictorial genealogy continues to Henry VIII in the same scribal and artistic hand, including Catherine of Aragon, Mary, and Henry (obit), the infant prince who died in 1511. Henry VIII’s subsequent wives and offspring were added to the genealogy later by a different artist and scribe, ending with Edward VI, presumably prior to his death in 1553.

Richard III

Some (especially Tudor historians and later Shakespeare) might suggest that Richard III, born on October 2nd 1452, was responible for much of this "thinning out" and he has been accused of involvement in the deaths of many of the possible contenders for the throne.

- Edward Prince of Wales: at the battlefield of Tewkesbury on May 4th 1471. An early reference to Richard’s involvement (he was a teenager at the time) is only found in the Tudor history, Anglica Historia (1534) by Polydore Vergil, which states that Edward was “crewelly murderyd” by the Duke of Clarence, Lord Hastings and the Duke of Gloucester. At the time of his birth, there was strife between Henry 's supporters and those of Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York, who had a claim to the throne and challenged the authority of Henry's officers of state. Henry was suffering from mental illness, and there were widespread rumours that the prince was the result of an affair between his mother and one of her loyal supporters. Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset and James Butler, 5th Earl of Ormond, were both suspected of fathering Prince Edward. According to contemporary sources, Edward was overtaken and slain in the battle during the rout of the Lancastrians, with some accounts attributing the deed to the Duke of Clarence, to whom the prince appealed to for help. Another version states that Clarence and his men found the grieving prince near a grove following the battle, and immediately beheaded him on a makeshift block, despite his pleas. Yet another account of Edward's death is given by three Tudor sources: The Grand Chronicle of London, Polydore Vergil, and Edward Hall. It was later dramatised by William Shakespeare in Henry VI, Part 3, Act V, scene v. Their story is that Edward was captured and brought before the victorious Edward IV and his brothers, the Duke of Clarence and the Duke of Gloucester, and his followers. The king received the prince graciously, and asked him why he had taken up arms against him. The prince replied defiantly, "I came to recover my father's heritage." The king then struck the prince across his face with his gauntlet hand, and Gloucester and Clarence killed the prince with their swords. However, none of these accounts appears in any of the contemporaneous sources, which all report that Edward died in battle.