Lavaux Map

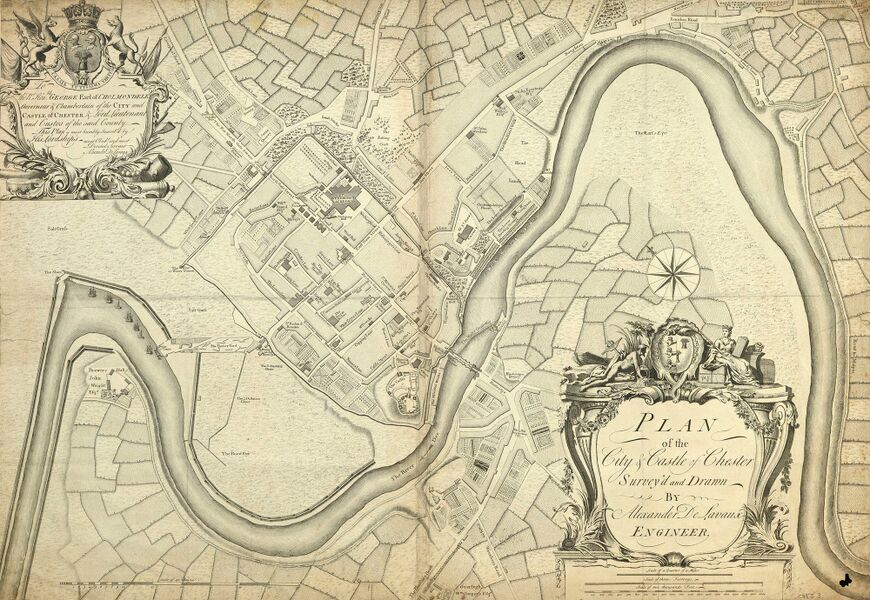

The Lavaux Map shows Georgian Chester as it was in 1745, duing the reign of George II. In around 1744 lead had been discovered on the land bequeathed to the city by Owen Jones and his bequest now became a much more valuable property. From the 1740s the Corporation connived with the Guilds' misapplication of the Owen Jones charity, who by the 1780s were dividing the proceeds indiscriminately among their members, whether poor or rich, as each guild came round in rotation. Admission to the guilds was closely regulated (see: Charters), some choosing to admit new members at inflated premiums, others to exclude new guildsmen as their own turn for the "bonanza" approached. The prospect of this pay-out appears to have increased corrruption in the assembly.

George II's French opponents encouraged a further rebellion by the Jacobites. In July 1745, the Old Pretender's son, Charles Edward Stuart, popularly known as Bonnie Prince Charlie or the Young Pretender, landed in Scotland, where support for his cause was highest. George, who was summering in Hanover, returned to London at the end of August. The Jacobites defeated British forces in September at the Battle of Prestonpans, and then moved south into England. A part of the Cheshire Militia was brought in to garrison the city and business came to a standstill. The city gates were bricked up, save for wickets at the Bridgegate and Eastgate, the walls were patrolled, cannon were mounted to command the bridge, and the Chester Castle defences were improved. The spring assizes were held at Flookersbrook in Hoole. George Cholmondeley put Chester in a state of defence, repairing the castle’s defences and adding raised batteries in the inner and outer wards and a raised platform with a parapet south-east of the Great Hall. The "military" architect Alexander de Lavaux was evidenttly engaged to draw up a plan to strengthen the fortifications, with massive earthworks in the form of a "star fort", but the work was never carried out.

Lavaux's map pf Chester is dedicated to George Cholmondeley. The Cholmondely coat of arms appears prominently on it. It is reasonable to assume that the survey for the map of Chester and the military tensions of the time might well have been connected. Apart from his political career, Lord Cholmondeley was also Lord Lieutenant of Cheshire and South Wales (less Denbighshire) from 1733 to 1760. He was promoted to colonel in 1745, major-general in 1755, and lieutenant-general in 1759.

On the march south, the Council met daily to discuss strategy, and at Derby on 5 December, its members overwhelmingly counselled retreat, the only significant dissenter being Charles. There was no sign of the promised French landing, and despite the large crowds that turned out to see them, only Manchester provided a significant number of recruits; Preston, a Jacobite stronghold in 1715, supplied three. Despite some early assistance, the French reneged on a promise of help. Losing morale, the Jacobites retreated back into Scotland. Charles faced George's military-minded son Prince William, Duke of Cumberland, in the Battle of Culloden, the last pitched battle fought on British soil. The ravaged Jacobite troops were routed by the government army. Charles escaped to France, but many of his supporters were caught and executed. Jacobitism was all but crushed; no further serious attempt was made at restoring the House of Stuart. Although the Jacobite army went nowhere near Chester, the city had been involved in heavy expense and had to turn to Sir Robert Grosvenor to obtain reimbursement from the government in 1746.

Features

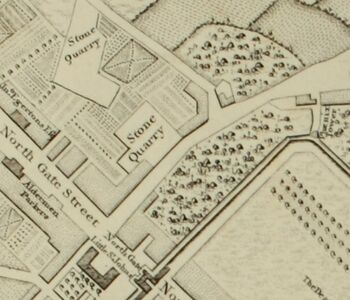

This plan was surveyed and drawn by Alexander de Lavaux, engineer and surveyor. As well as naming the owners of many houses, the plan includes informative details such as the "North Gate May Pole" and the "Water Engine", which was mentioned in Daniel Defoe’s diary record of his second visit to the city:

- "When I was formerly at this city, about the year 1690, they had no water to supply their ordinary occasions, but what was carried from the River Dee upon horses, in great leather vessels, like a pair of bakers panyers... But at my coming there this time, I found a very good water-house in the river, and the city plentifully supply'd by pipes, just as London is from the Thames; tho' some parts of Chester stands very high from the river".

Still much open space was left within the City Walls in 1745, although this map only shows the major buildings. The main routes into and out of the city are identified as: Parkgate Road, Liverpool Road, Warrington Road, St Anne's Rake, Northwich Road, London Road, the Road to Malpas, "Way to Eaton Boat", the Flintshire Road and the Wrexham Road. Of these the Wrexham Road is quite narrow, possibly indicating that it was among the least used.

Some further points to note are:

- Chester is shown before the construction of the Chester Canal in 1779. For more on this see Canal and Boatyard and Canalside. For the old Port see Portpool;

- The gallows near St Giles Cemetery are marked but not labled. This was the traditional place of Execution at Chester until hangings were transferred briefly to Northgate Gaol and later to the City Gaol. What is marked as Sandy Lane acually appears to be a continuation of what is now Barrel Well Hill and/or The Mount at Boughton. Sandy Lane also takes a quite different course than today, skirting around what appears to be a creek to rejoin the Malpas Road (modern Dee Banks). The main route to Malpas most likely starts along what is now Stocks Lane.

- To the left of the map the River Dee takes an apparent unnatural course which is entirely man-made: see Lower Reaches for more. During the eighteenth century Chester’s trade had diminished considerably thanks to the gradual decrease in the navigability of the river. Using engineers from the Netherlands an artificial channel was excavated 1732-36. It was paid for by local merchants and the Chester Corporation and much used for the transport of Cheshire Cheese. By the time of this map, the Watertower and the Watergate are now far from the River Dee except during exceptional tides. Brewers Hall is shown in some detail. The Sluce marked is at the end of Flookersbrook.

- To the right of the map the "Straight Mile" of the River is not so straight alongside the Earls Eye. This is the secopn of the river used for the Regatta.

- The City Walls appear to come right down to the River Dee just north of the Bridgegate. The Groves having not yet been extended that far. What we now call the Groves is marked as "The watering place for horses", "Dee Side Walks" and "Lord Derby's Dee Side". The Lord Derby in question is covered on the pages relating to Shakespeare and Chester. Strangely there are no Recorder's Steps labeled, but a feature on the walls near "The Skinners Hall" may be them.

- Each individual field appears to be laid out according to its usage. However, these are not drawn accurately

A high resolution scan of this map can be purchased from the Chester Records Office (on CD). A Hi-res version of the map is also available on-line.

History

This is a rare, important plan of Chester and one of the earliest large scale plans of the city. It is one of many published in the middle of the eighteenth century which importantly record cities before rapid industrialisation. The copper-engraved plan is by the surveyor Alexander De Lavaux and one auction site states of him "about who little is known other than his self styled description as an Engineer". The engraving is attributed to Richard Parr (fl.1723-51) who worked especially closely with John Rocque the great publisher of many large scale maps. The decorative features contain subtle details: the female fiqure above the title panel sits upon a package bounnd with twine, which has upon it a "merchants mark" which is that of the "Wool Staplers" - these buy wool from the producer, sort and grade it, and sell it on to manufacturers. Before the 17th century a staple was also a particular type of market, "a place appointed by royal authority, in which a body of merchants had exclusive right of purchase of certain goods destined for export". The now best known English staple was at Calais but in medieval times there were, at various times, many others throughout the kingdoms of England and Ireland and the facing coast of the Low Countries all involved, though not exclusively, with the English wool trade. The "queen" also has a mace, and therefore this may be an allusion to the "Woolsack" - the traditional seat of the Lord Chancellor in the House of Lords. The other figure appears to be a shipwrecked mariner, but the figures of a queen and Nepture, adapted to local usage, were common on maps at the time.

The cartographic detail is remarkable with, as was the fashion at the time, notable town resident’s buildings being identified as are all of the roads including even the Maypole on Northgate Street. So far as is known, Lavaux did not produce maps of other cities. The style is similar to that of cartographer Alexander Downing, who was active at around the same time. It also has many features in common with the map of Amsterdam produced by Henry de Leth. Many of the houses marked on the map still exist and research has revealed much of the story of their occupants. For example, the house of Robert Foulques at what is now 25 Castle Street (in 2019 the office of the local MP) has an interesting history.

Lavaux's past before Chester was not without incident. Alexander De Lavaux was born in Berlin around 1704 and had at his entrance into Prussian service had the rank of lieutenant and engineer. In 1729, at the age of 25 he was employed by the Dutch "Society of Suriname". With an appointment as cartographer in Suriname he was given the rank of ensign. He made several campaigns against the "Maroons", and produced a first map of the Suriname River. In 1731 the Directors of the Society of Suriname discovered that the existing maps were not of sufficient quality to indicate the condition of the land and the location of the plantations. By May 1734 Lavaux had been working for over two years on a new and accurate map of Suriname. In 1725 he visited Amsterdam, was promoted to captain and went back to Suriname, apparently travelling via New England..

He did not get on with the new Governor (Gerrit van de Schepper?) and in 1741 deserted without warning on an English ship to St. Eustatius and then to the British colony of Saint Christopher (now St. Kitts). At the end of 1741 he was extradited by and put in prison at Fort Zeelandia. It took until June 1743 for the court-martial verdict (which demanded a death penalty). Lavaux meanwhile was diagnosed as insane (presumably due to prison conditions). The sentence was commuted in 1744 to expulsion from the military service and banishment from Suriname.

Within two years Lavaux must have traveled to Chester and begun work on his map. Lavaux's reasons for coming to Chester remain unknown, but the map is dedicated to George Cholmondeley, who was Vice Admiral of Cheshire at the time, and appears to have Dutch ancestry through his mother.

Fort Zeelandia has now become a museum. Notably, the Lavaux map of Chester omits the City Gaol.

Gallery

The Roodee;

City Walls near the Recorder's Steps;

City Walls near Newgate;

The Shambles;

Upper Bridge Street;

The Hermitage as shown in the Lavaux Map (1745);

Sources and Links

- Lavaux on Dutch Wikipedia;

- Another high res version (Harvard);

- Bijlsma, R. (1921) "Alexander de Lavaux en zijne Generale kaart van Suriname 1737", De West-Indische Gids, jrg 2, nr. 2, pp. 397-40.

- "Van de kaart vegen; Alexander de Laveaux, kaartenmaker", Museumstof 55, website Surinaams Museum;

- More on him in "Cloggie";