Legio XX

Apart from a short period when Roman Chester was first built the Roman force here was Legio XX. Roman historian Cassius Dio writes of them:

- "…the Twentieth, called both Valeria and Victrix, in Upper Britain. All these I believe, were the troops which Augustus took over and kept, together with the legion known as the Twenty-Second, which is quartered in Germany. The legion I have entitled Valeria is not given this name by all, and in fact no longer uses that designation. At any rate these are the legions which are still in service today, out of those maintained by Augustus himself and by other emperors, in consequence of which such legions have come to bear the name Gemina.” - Cassius Dio, Roman History (LV.23.6-7)

Roman Legions are fascinating as a persistent social structure. They could last for hundreds of years, often spend decades if not centuries far from "home". Had strict rules as regards marriage, harsh discipline (although they did mutiny) and could be moved suddenly across the Empire. They were impressive builders - Roman Chester was built by the Legions who occupied it: they could not just get the "contractors" in.

There are many "issues of interest" with Legio XX:

- when/where was it formed, or when/where was it disbanded?;

- what were they called (nicknamed) and when and how did they get that name?;

- "What have the Romans ever done for us.." (apart from written language..);

Celts and Germans

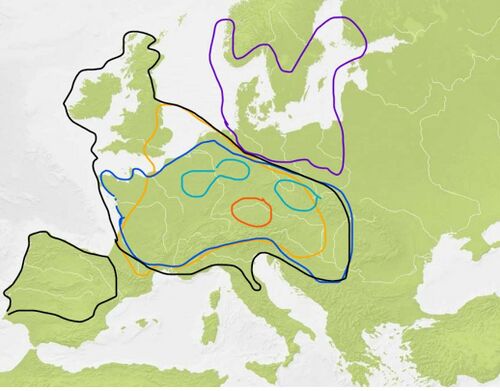

In order to understand what was happening on the eastern frontier of the Roman Empire at the time of Augustus it is useful to review the relationship between the Celts and the Germanic peoples. The Germanic peoples (also called Teutons, Suebi, or Gothi in older literature) were an ethnolinguistic group of Northern European origin identified by Roman-era authors as distinct from neighbouring Celtic peoples (also called Gauls), and identified in modern scholarship as speakers, at least for the most part, of early Germanic languages. Julius Caesar’s "Bellum Gallicum" is the main primary source on the Gauls and the Germans. However, it is laced with biases and political intentions and is as much propaganda as history.

Celts

The first recorded use of the name of Celts – as Κελτοί (Keltoi) in Greek – to refer to a culture was by Hecataeus of Miletus, the Greek geographer, in 517 BC, when writing about a people living near Massilia (modern Marseille - founded c.600 BC by the Greeks). In the fifth century BC, Herodotus referred to Keltoi living around the head of the Danube and also in the far west of Europe. The etymology of the term Keltoi is unclear. In the 1st century BC, Julius Caesar reported that the people known to the Romans as Gauls (Latin: Galli) called themselves Celts. The English form Gaul (first recorded in the 17th century) and Gaulish come from the French Gaule and Gaulois, a borrowing from Frankish Walholant, the root of which is Proto-Germanic *walha-, "foreigner, Roman, Celt", whence the English word Welsh (Old English wælisċ < *walhiska-).

Celtic refers to a family of languages and, more generally, means "of the Celts" or "in the style of the Celts". Several archaeological cultures are considered Celtic in nature, based on unique sets of artefacts. Earlier theories held that these similarities suggest a common racial origin for the various Celtic peoples, but more recent theories hold that they reflect a common cultural and language heritage more than a genetic one. Celtic cultures seem to have been widely diverse, with the use of a Celtic language being the main thing they had in common. The spread of iron-working led to the development of the Hallstatt culture directly from the late Bronze Age Urnfield Culture (c. 700 to 500 BC). The Hallstatt culture was succeeded by the La Tène Culture of central Europe, which was largely overrun by the Roman Empire.

Germans

A Proto-Germanic population is believed to have emerged during the Nordic Bronze Age, which developed out of the so-called "Battle Axe Culture" in southern Scandinavia. During the Iron Age various Germanic tribes began a southward expansion at the expense of Celtic peoples, which led to centuries of sporadic violent conflict with ancient Rome. It is from Roman authors that the term "Germanic" originated. In book six of his "Gallic Wars" Caesar describes the differences between the Germans who east of the Rhine, and the Gauls. Caesar describes both the Gauls and Germans as violent people. However, according to Caesar the Germans are incapable of civilization and present a threat to Rome and to Roman-dominated Gaul.

Julius Caesar describes the Suebi in his De Bello Gallico as the "largest and the most warlike nation of all the Germans". In 58 BC Caesar confronted a large army led by a Suevic King named Ariovistus in 58 BC who had been settled for some time in Gaul already, at the invitation of the Gaulish Arverni and Sequani as part of their war against the Aedui. He had already been recognized as a king by the Roman senate. Ariovistus forbade the Romans from entering into Gaul. Caesar on the other hand saw himself and Rome as an ally and defender of the Aedui. The forces Caesar faced in battle were composed of "Harudes, Marcomanni, Tribocci, Vangiones, Nemetes, Sedusii, and Suevi". While Caesar was preparing for conflict, a new force of Suebi was led to the Rhine by two brothers, Nasuas and Cimberius, forcing Caesar to rush in order to try to avoid the joining of forces. Caesar defeated Ariovistus in battle, forcing him to escape across the Rhine. Cassius Dio (c. 150 - 235 AD) wrote the history of Rome for a Greek audience. He reported that, shortly before 29 BC, the Suebi crossed the Rhine, only to be defeated by Gaius Carrinas who, along with the young Octavian Caesar, celebrated a triumph in 29 BC.

Rome

By 390, several Celtic tribes were invading Italy from the north as their culture expanded throughout Europe. The Romans were alerted to this when a particularly warlike tribe, the Senones, invaded two Etruscan towns close to Rome's sphere of influence. These towns, overwhelmed by the enemy's numbers and ferocity, called on Rome for help. The Romans met the Gauls in pitched battle at the Battle of Allia River around 390–387 BC. The Gauls, led by the chieftain Brennus, defeated the Roman army of approximately 15,000 troops, pursued the fleeing Romans back to Rome, and sacked the city before being either driven off or bought off. Brennus's sack of Rome was the only time in 800 years the city was occupied by a non-Roman army before the fall of the city to the Visigoths in 410 AD.

By the beginning of the 3rd century BC, Rome had established itself as the major power in Italy, but had not yet come into conflict with the dominant military powers of Mediterranean: Carthage and the Greek kingdoms. It was not until after the Second Punic War that the alliances which made up the Roman state started to harden into something more like an empire. In contrast, Roman expansion into Hispania and Gaul occurred as a mix of alliance-seeking and military occupation. The major part of the Punic Wars, between the Carthaginians and the Romans, was fought on the Iberian Peninsula. Carthage gave control of the Iberian Peninsula and much of its empire to Rome in 201 BC as part of the peace treaty after its defeat in the Second Punic War, and Rome completed its replacement of Carthage as the dominant power in the Mediterranean area. The Roman Republic began its takeover of Celtic Gaul in 121 BC, when it conquered and annexed the southern reaches of the area. Julius Caesar significantly advanced the task by defeating the Celtic tribes in the Gallic Wars of 58-51 BC.

In the course of his Gallic Wars, Julius Caesar invaded Britain twice: in 55 and 54 BC. On the first occasion Caesar took with him only two legions, and achieved little beyond a landing on the coast of Kent. The second invasion consisted of 628 ships, five legions and 2,000 cavalry. The force was so imposing that the Britons did not dare contest Caesar's landing in Kent, waiting instead until he began to move inland. Caesar eventually penetrated into Middlesex and crossed the Thames, forcing the British warlord Cassivellaunus to surrender as a tributary to Rome and setting up Mandubracius of the Trinovantes as client king. Caesar was eager to return to Gaul for the winter due to growing unrest there and wrote to Cicero on 26 September, confirming the result of the campaign, with hostages but no booty taken, and that his army was about to return to Gaul. He then left, leaving not a single Roman soldier in Britain to enforce his settlement. Whether the tribute was ever paid is unknown. Caesar's enthroning of Mandubracius marked the beginnings of a system of client kingdoms in Britain, thus bringing the island into Rome's sphere of political influence. Diplomatic and trading links developed further over the next century.

In 22 BC, imperial administration of Gaul was reorganized, establishing the provinces of Gallia Aquitania, Gallia Belgica and Gallia Lugdunensis.

In the 2nd century BC, Roman involvement in the Greek east remained a matter of alliance-seeking, but this time in the face of major powers that could rival Rome. According to Polybius, who sought to trace how Rome came to dominate Greece in less than a century, this was mainly a matter of several Greek city-states seeking Roman protection against the Macedonians and Seleucids. In contrast to the west, the Greek east had been dominated by empires for centuries, and Roman influence and alliance-seeking led to wars with these empires. The Roman Republic, which had replaced Rome's monarchy in the 6th century BC, became severely destabilized in a series of civil wars and political conflict. In the late Republican period (107 BC to 27 BC), it became increasingly common for victorious commanders to march their armies back into Rome and seize power to ensure their troops received land they had been promised. This led to recurrent civil wars, eventually transforming Rome from a moderately democratic republic into an autocratic empire.

In the mid-1st century BC Julius Caesar was appointed as perpetual dictator and then assassinated in 44 BC. Civil wars and proscriptions continued, culminating in the victory of Octavian, Caesar's adopted son, over Mark Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC. The following year Octavian conquered Ptolemaic Egypt, ending the Hellenistic period that had begun with the conquests of Alexander the Great of Macedon in the 4th century BC. Octavian's power was then unassailable and in 27 BC the Roman Senate formally granted him overarching power and the new title Augustus, effectively making him the first emperor. Augustus and his successors distributed the Roman army along the frontier, ensuring that no single general had command of more than a small fraction of Rome’s troops at any one time. And emperors reduced the soldiers’ dependence on their commanders by paying them salaries from the imperial treasury.

History of Legio XX

Direct references to Legio XX are largely confined to the first century and the events of AD 6, AD 14-16, AD 60 and AD 69. The written sources for the history of Legio XX are:

- Velleius Paterculus (c. 19 BC – c. AD 31): His History (Latin: Historiae), written in a highly rhetorical style, covers the period from the end of the Trojan War to the death of Livia in AD 29, but is most useful for the period from the death of Julius Caesar in 44 BC. to the death of Augustus in 14 AD;

- Publius (or Gaius) Cornelius Tacitus (c. 56 – c. 120 AD) lived in what has been called the Silver Age of Latin literature, and is known for the brevity and compactness of his Latin prose, as well as for his penetrating insights into the psychology of power politics. The text of Tacitus is available online. The work most relevant to Legio XX is the life of his father-in-law, Agricola, the general responsible for much of the Roman conquest of Britain, mainly focusing on his campaign in Britannia (De vita et moribus Iulii Agricolae). Agricola was at one point commander of Legio XX;

- Ptolemy (c. AD 100 – c. 170) was a mathematician, astronomer, geographer and astrologer. He lived in the city of Alexandria in the Roman province of Egypt.

- The Antonine Itinary is a register of the stations and distances along various roads. Seemingly based on official documents, possibly from a survey carried out under Augustus. Almost nothing is known of its date or author. Scholars consider it likely that the original edition was prepared at the beginning of the 3rd century. Although it is traditionally ascribed to the patronage of the 2nd-century Antoninus Pius, the oldest extant copy has been assigned to the time of Diocletian and the most likely imperial patron—if the work had one—would have been Caracalla (4 April 188 – 8 April 217).

- Cassius Dio ( c. 155 – c. 235) was a Roman statesman and historian of Greek and Roman origin. He published 80 volumes of history on ancient Rome, beginning with the arrival of Aeneas in Italy. The volumes documented the subsequent founding of Rome (753 BC), the formation of the Republic (509 BC), and the creation of the Empire (31 BC), up until 229 AD. Written in ancient Greek over 22 years, Dio's work covers approximately 1,000 years of history. Many of his 80 books have survived intact, or as fragments, providing modern scholars with a detailed perspective on Roman history;

- Zosimus (fl. 490s–510s) was a Greek historian who lived in Constantinople during the reign of the Eastern Roman Emperor Anastasius I (491–518). Zosimus' "Historia Nova" (Ἱστορία Νέα, "New History") is written in Greek in six books. For the period from 238 to 270, he apparently uses Dexippus; for the period from 270 to 404, Eunapius; and after 407, Olympiodorus.

Prior to Britain

The original founding of Legio XX may have been as early as 40 BC, for one of Octavian's campaigns. The legion possibly played a part in his Actium campaign and his victory over Antony and Cleopatra, in 31 BC, which brought to an end the "Final War of the Roman Republic". If not, it may have been formed shortly thereafter. Octavian dissolved many of the earlier legions after the battle and re-formed new ones in a numerical sequence up to XXVIII. Whether any part of an original Legio XX formed a part of the new one is not known.

Legio XX was probably part of the large Roman force that fought in the Cantabrian Wars in Hispania from 25 to 19 BC. This was the conquest of the remaining part of northern Spain which the Romans had not taken from Carthage. However, that may be a misunderstanding based on the use of wings on coins struck in connection with the wars and a wrong interpretation of the name "Valeria" as meaning eagle.

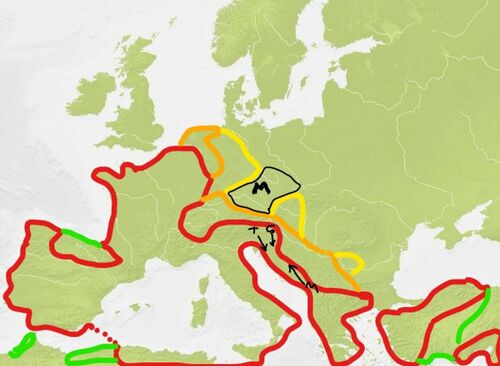

Illyricum

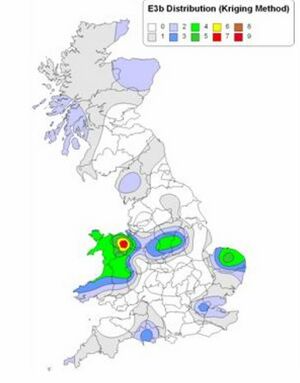

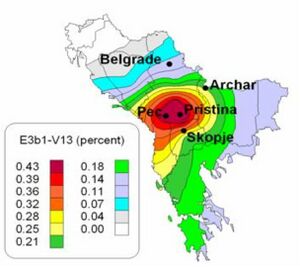

Legio XX was afterwards based in Illyricum. This may shed some light both on the name of the legion and it's genetic impact on the population of North Wales. Illyricum was a Roman province that existed from 27 BC to sometime during the reign of Vespasian (69–79 AD). The province comprised Illyria/Dalmatia and Pannonia. Illyria included the area along the east coast of the Adriatic Sea and its inland mountains. It was originally an area with a Celtic culture. With the creation of this province it came to be called Dalmatia. It was in the south, while Pannonia was in the north. Illyria/Dalmatia stretched from the River Drin (in modern northern Albania) to Istria (Croatia) and the River Sava in the north. The area roughly corresponded to modern northern Albania, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina and coastal Croatia. Pannonia was the plain which lies to its north, from the mountains of Illyria/Dalmatia to the westward bend of the River Danube, and included modern Vojvodina (in modern northern Serbia), northern Croatia and western Hungary. As the province developed, Salona (near modern Split, Croatia) became its capital.

In the great Pannonian revolt (Bellum Batonianum) of 6 AD, Velleius Paterculus (c. 19 BC – c. AD 31) records (2.112) that Legio XX served with distinction. In 6 CE, the Roman general (and future emperor)Tiberius was about to lead at least eight legions (VIII from Pannonia, XV and XX from Illyricum, XXI from Raetia, XIII, XIV and XVI from Germania Superior and an unknown unit) against king Maroboduus of the Marcomanni in Czechia. Tiberius ordered the local tribes to provide auxiliary contingents. When these troops gathered they rebelled under the leadership of Bato, a Daesitiate, and defeated a Roman force sent against them. Although this war is sometimes described as having been fought by the Daesitiatae and the Breuci only, Cassius Dio identified the forces led by Bato the Daesitiate as Dalmatian, indicating a broader composition.

According to current estimation, the following five legions were stationed in Illyricum at the outbreak of the great rebellion in AD 6: IX Hispana, XIII and XIV Gemina, XV Apollinaris and XX (not yet named Valeria Victrix). Aquileia retained its great strategic role as an important military, administrative and logistic base during the Pannonian War and the great rebellion; Roman troops were temporarily stationed in or around the city, particularly Legio XX, before it was transferred to Burnum in Dalmatia, as the first legion to be stationed there. The reason for its location was the need for the control of traffic around the Krka River. Building was initiated by the Roman governor for Dalmatia Publius Cornelius Dolabella.

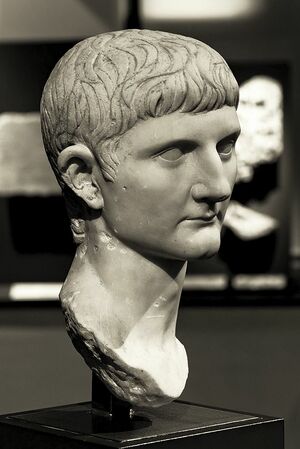

Initially, part of Legio XX under the command of the governor Marcus Valerius Messalla Messallinus was sent on ahead from Carnuntum, the capital of Pannonia Superior, to engage the rebels. Outnumbered and initially unsuccessful, Messalinus was able nonetheless to put the enemy to flight and was honoured with ornamenta triumphalia. During one battle the legion broke through the enemy lines, but then became cut off and surrounded, and had to fight its way back out again. Paterculus (who was present in the region as a serving soldier) records:

- "An exploit of Messalinus in the first summer of the war, fortunate in its issue as it was bold in undertaking, must here be recorded for posterity. This man, who was even more noble in heart than in birth, and thoroughly worthy of having had Corvinus as his father, and of leaving his cognomen to his brother Cotta, was in command in Illyricum, and, at the sudden outbreak of the rebellion, finding himself surrounded by the army of the enemy and supported by only the twentieth legion, and that at but half its normal strength, he routed and put to flight more than twenty thousand, and for this was honoured with the ornaments of a triumph. .. At this critical moment, when some tribunes of the soldiers had been slain by the enemy, the prefect of the camp and several prefects of cohorts had been cut off, a number of centurions had been wounded, and even some of the centurions of the first rank had fallen, the legions, shouting encouragement to each other, fell upon the enemy, and not content with sustaining their onslaught, broke through their line and wrested a victory from a desperate plight. " (Paterculus Book 2, chapter 112)

Cassius Dio gives a slightly different version of the revolt to Paterculus. In 8 AD the Dalmatians and the Pannonians, ravaged by famine and disease, wanted to sue for peace but were prevented from doing so by the rebels, who had no hope of being spared by the Romans and so continued to resist. Tiberius had pursued a policy of scorched earth to starve the Pannonians. Cassius Dio also noted that there were grain shortages in Rome the previous year and that later in this year the famine abated. We do not know how widespread this was and whether it touched other Mediterranean areas, including Dalmatia and Pannonia, and thus was a contributory factor. According to Cassius Dio, Bato the Breucian overthrew Pinnes, the king of the Breuci. He became suspicious of his subject tribes and demanded hostages from the Pannonian garrisons. Bato the Daesitiate defeated him in battle and pinned him in a stronghold. He was handed over to Bato the Daesitiate and was executed. After this many Pannonians broke with the rebels. Marcus Plautius Silvanus conducted a campaign against the tribes, conquered the Breuci and won over the others without a battle. Bato the Daesitiate withdrew from Pannonia, occupied the passes leading to Dalmatia and ravaged the lands beyond.

Velleius Paterculus wrote that the harsh winter brought rewards because in the following summer all of Pannonia sought peace. Therefore, a bad winter probably also played a part. The Pannonians laid down their arms at the River Bathinus. Bato was captured and Pinnes surrendered. In 9 AD the war was restricted to Dalmatia. Velleius Paterculus wrote that Augustus gave the chief command of all the forces to Marcus Aemilius Lepidus. In the summer Lepidus made his way to Tiberius through areas which had not been affected by the war, and was attacked by fresh local forces. Lepidus defeated them, ravaged the fields, and burnt houses, later reaching Tiberius. This campaign ended the war. Two Dalmatian tribes, the Pirustae and Daesitiates, who had been almost unconquerable because of their mountain strongholds, the narrow passes in which they lived, and their fighting spirit, were almost exterminated. The Romans, aside from committing atrocities during the war, split up Illyrian tribes into different groups from the ones they had previously composed. The administrative civitates of the Osseriates, Colapiani and Varciani were probably created from the Breuci. Other members of tribes were probably sold as slaves, or deported to different locations.

Despite the rebellion, the Illyrians went on, alongside their neighbours the Thracians, to become the backbone of the Roman army. By the 2nd century, with roughly half the Roman army deployed on the Danube frontier, the auxilia and legions alike were dominated by Illyrian recruits. In the 3rd century, Illyrians largely replaced Italians in the senior officer echelons of praefecti of auxiliary regiments and tribuni militum of legions. Finally, from AD 268 to 379, virtually all emperors, including Diocletian and Constantine the Great were Romanised Illyrians from the provinces of Dalmatia, Moesia Superior and Pannonia. These were members of a military aristocracy, outstanding soldiers who saved the empire from collapse in the turbulent late 3rd century.

The Roman historian Suetonius described the Bellum Batonianum as the most difficult conflict faced by Rome since the Punic Wars two centuries earlier. Nearly half of all Roman legions in existence were sent to the Balkans to end the revolt, which was itself triggered by constant neglect, endemic food shortages, high taxes, and harsh behaviour on the part of the Roman tax collectors. In the year that it ended the Romans found themselves in a new conflict when an alliance of Germanic tribes ambushed and destroyed three Roman legions and their auxiliaries. The alliance was led by Arminius, a Germanic officer of Varus's auxilia. Arminius had acquired Roman citizenship and had received a Roman military education, which enabled him to deceive the Roman commander methodically and anticipate the Roman army's tactical responses. Had the Germanic tribes under Arminius formed an alliance with those under Maroboduus and attacked during the Pannonian Revolt it might well have meant an early end for the Roman Empire.

Germania

Germania was the Roman term for the historical region in north-central Europe initially inhabited mainly by Germanic tribes. It extended from the Danube and Main in the south to the Baltic Sea, and from the Rhine in the west to the Vistula. The ethnonym "Germani" is most likely Gallic in origin. Jacob Grimm derived it from a Celtic term for "shouting; noisy", and argued that the name represents a literal translation of the endonym "Tungri". Johann Kaspar Zeuss derived the name from the Celtic word for "neighbour". The occupied Lesser Germania was divided into two provinces: Germania Inferior (Lower Germania) (approximately corresponding to the southern part of the present-day Netherlands) and Germania Superior (Upper Germania) (approximately corresponding to present-day Switzerland, South West Germany and Alsace). The Romans under Augustus began to conquer and defeat the peoples of Germania Magna in 12 BC, having the Legati (generals) Germanicus, and Tiberius leading the Legions. By 6 AD, all of Germania up to the River Elbe was temporarily pacified by the Romans as well as being occupied by them, with Publius Quinctilius Varus being appointed as Germania's governor. The Roman plan to complete the conquest and incorporate all of Magna Germania into the Roman Empire was frustrated when three Roman legions under Varus command were annihilated by the German tribesmen in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in 9 AD.

After Publius Quinctilius Varus' disasterous defeat in 9 AD and the destruction of Legio XVII, XVIII and XIV, Tacitus records that Legio XX was moved to Oppidum Ubiorum (Cologne) and then to Novaesium (Neuss) in Germany, and in the following years took part in Germanicus' punitive campaigns across the Rhine. He attacked the Marsi with the element of surprise. The Bructeri, Tubanti, and Usipeti were roused by the attack and ambushed Germanicus on the way to his winter quarters, but were defeated with heavy losses. The next year was marked by two major campaigns and several smaller battles with a large army estimated at 55,000–70,000 men, backed by naval forces. The crises of AD 6-9 had led to the retention of many due for discharge. Some had probably served throughout the Pannonian wars, the campaigns against the Marcomanni and the difficult suppression of the Pannonian revolt and now found themselves in garrison on the northern frontier with little sign of imminent discharge. On the death of Augustus in AD 14 the legions of Germania Inferior - the First, Fifth, Twentieth and Twenty-First, now under the command of Aulus Caecina Severus - finally rose in mutiny.

Caecina apparently lost his nerve over the mutiny. He initially made no move to stop the disorder spreading, and when centurions sought his protection, he agreed, albeit reluctantly, to hand them over to the legionaries to be tortured and killed. Tacitus writes as follows:

- "During the same days almost, and from the same causes, the legions of Germany mutinied, in larger numbers1 and with proportionate fury; while their hopes ran high that Germanicus Caesar, unable to brook the sovereignty of another, would throw himself into the arms of his legions, whose force could sweep the world. There were two armies on the Rhine bank: the Upper, under the command of Gaius Silius; the Lower, in charge of Aulus Caecina. The supreme command rested with Germanicus, then engaged in assessing the tribute of the Gaulish provinces. But while the forces under Silius merely watched with doubtful sympathy the fortunes of a rising which was none of theirs, the lower army plunged into delirium. The beginning came from the twenty-first and fifth legions: then, as they were all stationed, idle or on the lightest of duty, in one summer camp on the Ubian frontier,3 the first and twentieth as well were drawn into the current." (Annals, Chap 31)

Germanicus turned down the offer of being made Emperor. The mutiny was quelled only by meeting the demands of the troops following a direct confrontation with Germanicus:

- " ...it was decided to have letters written in the name of the emperor, directing that all men who had served twenty years should be finally discharged; that any who had served sixteen should be released from duty and kept with the colours under no obligation beyond that of assisting to repel an enemy; and that the legacies claimed should be paid and doubled. The troops saw that all this was invented for the occasion, and demanded immediate action. The discharges were expedited at once by the tribunes: the monetary grant was held back till the men should have reached their proper quarters for the winter. The fifth and twenty-first legions declined to move until the sum was made up and paid where they stood, in the summer camp, out of the travelling-chests of the Caesar's suite and of the prince himself. The legate Caecina led the first and twentieth legions back to the Ubian capital..."

There were however some executions.

In spring 15 CE, Legatus Caecina Severus invaded the Marsi a second time with about 25,000–30,000 men, causing great havoc. Meanwhile, Germanicus' troops had built a fort on Mount Taunus from where he marched with about 30,000–35,000 men against the Chatti. Many of the men fled across a river and dispersed themselves in the forests. Germanicus next marched on Mattium (caput gentis) and burned it to the ground.] After initial successful skirmishes in summer 15 CE, including the capture of Arminius' wife Thusnelda, the army visited the site of the first battle. According to Tacitus, they found heaps of bleached bones and severed skulls nailed to trees, which they buried.

Germanicus' campaign had been taken to avenge the Teutoburg slaughter and also partially in reaction to indications of mutinous intent amongst his troops. Arminius, who had been considered a very real threat to stability by Rome, was now defeated. Once his Germanic coalition had been broken and honour avenged, the huge cost and risk of keeping the Roman army operating beyond the Rhine was not worth any likely benefit to be gained. Tacitus, with some bitterness, claims that Tiberius' decision to recall Germanicus was driven by his jealousy of the glory Germanicus had acquired, and that an additional campaign the next summer would have concluded the war and facilitated a Roman occupation of territories between the Rhine and the Elbe. After being recalled from Germania, Germanicus celebrated a triumph in Rome in AD 17, the first full triumph that the city had seen since Augustus' own in 29 BC. As a result, in AD 18 Germanicus was granted control over the eastern part of the empire, just as both Agrippa and Tiberius had received before, and was clearly the successor to Tiberius. Germanicus survived a little over a year before dying, accusing Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso, the governor of Syria, of poisoning him.

In 21, a mixed subunit of Legio XX and XXI Rapax, commanded by an officer from I Germanica, was sent out to suppress the rebellion of the Turones in Gaul (Tacitus: Annals Book 3.40), who had revolted against the heavy Roman taxation under a nobleman named Julius Sacrovir and Julius Florus.

Almost twenty years later (AD 39-40), the Twentieth was employed during the Germanic war of Caligula. The details, however, are not fully understood. It has been suggested that the purpose of these expeditions were to give some experience to newly formed units and free up more seasoned troops for a possible invasion of Britain. It is also possible that Caligula's landing in Britain in AD 40 was a rehearsal for a full scale invasion. The story is frequently told that Caligula ordered his troops to pick up sea-shells, and this is see as evidence that he was insane. However, it is possible that his reference to "shells" (musculi) was a reference to "huts" in soldier's slang. This was later transcribed by Suetonius as "conchae".

In 41 AD, the Praetorian Guard assassinated Caligula, together with his wife Caesonia and his daughter. He was 29. Only the common people, who benefited from his extravagant spending, lamented his death.

In Britain

Between 55 BC and the 40s AD, the status quo of tribute, hostages, and client states without direct military occupation, begun by Caesar's invasions of Britain, largely remained intact. Augustus prepared invasions in 34 BC, 27 BC and 25 BC. The first and third were called off due to revolts elsewhere in the empire, the second because the Britons seemed ready to come to terms. According to Augustus's Res Gestae, two British kings, Dubnovellaunus and Tincomarus, fled to Rome as supplicants during his reign, and Strabo's Geography, written during this period, says Britain paid more in customs and duties than could be raised by taxation if the island were conquered:

- "At present, however, some of the chieftains there, after procuring the friendship of Caesar Augustus by sending embassies and by paying court to him,150 have not only dedicated offerings in the Capitol, but have also managed to make the whole of the island virtually Roman property. Further, they submit so easily to heavy duties, both on the exports from there to Celtica and on the imports from Celtica (these latter are ivorya chains and necklaces, and amber-gems and glass vessels and other petty wares of that sort), that there is no need of garrisoning the island; for one legion, at the least, and some cavalry would be required in order to carry off tribute from them, and the expense of the army would offset the tribute-money; in fact, the duties must necessarily be lessened if tribute is imposed, and, at the same time, dangers be encountered, if force is applied."

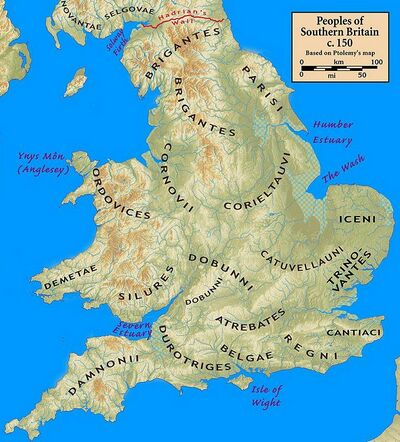

By the 40s AD, the political situation within Britain was in ferment. The Catuvellauni had displaced the Trinovantes as the most powerful kingdom in south-eastern Britain, taking over the former Trinovantian capital of Camulodunum (Colchester). The Atrebates tribe whose capital was at Calleva Atrebatum (Silchester) had friendly trade and diplomatic links with Rome and Verica was recognised by Rome as their king, but Caratacus' Catuvellauni conquered the entire kingdom some time after AD 40 and Verica was expelled from Britain. His exile gave Claudius an excuse to begin his invasion.

Legio XX was part of the army sent by Emperor Claudius to invade Britain in 43 AD. At the time the nominal commander of Legio XX was Tiberius Claudius Balbilus the astrologer of Emperor Claudius.

Its first base was Camulodunum (Colchester), then it moved west in 47 or 49, possibly to Kingsholm (near Gloucester), and probably to Usk shortly afterwards. There was sporadic fighting against such famous enemies as Caratacus, and against the Silures and Ordovices in south-eastern Wales.

Legio XX took part in the Battle of Caer Caradoc, the final battle in Caratacus's resistance to Roman rule. Fought in 50 AD, the Romans defeated the Britons and thus secured the southern areas of the province of Britannia. Caratacus chose a battlefield in hilly country, placing the Britons on the higher ground. His forces were probably primarily made up of warriors from the Ordovices though there may have been some Silures as well. This position made both approach and retreat difficult for the Romans, and comparatively easy for his own forces. Where the slope was shallow, he built rough stone ramparts, and placed armed men in front of them. In front of them was a river which appeared difficult to cross, but in the event the Roman troops crossed it easily. The Roman commander, Publius Ostorius Scapula, was reluctant to assault the British lines, but the enthusiasm of his men won him over. The river was crossed without difficulty. The Roman soldiers came under a rain of missiles, but employed the testudo formation to protect themselves and dismantled the stone ramparts. Once inside the defences, the Romans broke through in bloody fighting. The Britons withdrew to the hilltops, but the Romans kept up the pursuit. Their lines broke, and they were caught between the heavily armed legionaries and the lightly armed auxiliaries. Caratacus's wife, son, and daughter were captured and his brother surrendered, but Caratacus himself escaped. He fled north, seeking refuge among the Brigantes. The Brigantian queen, Cartimandua, however, was loyal to Rome, and she handed him over in chains. He was exhibited as part of the emperor Claudius's Roman triumph in Rome. He gave a speech which persuaded the emperor to spare him and his family. His defeat was publicly likened by the Senators to some of Rome's greatest victories, and Ostorius Scapula was awarded triumphal ornaments for defeating him.

The site of the battle is unknown. Tacitus' account limits the location to the territory of the Ordovices, whose boundaries are no longer known but included a large area of what is now central and northern Wales.

Boudica's Revolt

Probably the best-known event in the history of Legio XX is the defeat of Boudica's Revolt in 60. At the time Legio XX was engaged (under Suetonius Paulinus) in mopping-up the Druids in North Wales as described by Tacitus:

- "He prepared accordingly to attack the island of Mona, which had a considerable population of its own, while serving as a haven for refugees; and, in view of the shallow and variable channel, constructed a flotilla of boats with flat bottoms. By this method the infantry crossed; the cavalry, who followed, did so by fording or, in deeper water, by swimming at the side of their horses. On the beach stood the adverse array, a serried mass of arms and men, with women flitting between the ranks. In the style of Furies, in robes of deathly black and with dishevelled hair, they brandished their torches; while a circle of Druids, lifting their hands to heaven and showering imprecations, struck the troops with such an awe at the extraordinary spectacle that, as though their limbs were paralysed, they exposed their bodies to wounds without an attempt at movement. Then, reassured by their general, and inciting each other never to flinch before a band of females and fanatics, they charged behind the standards, cut down all who met them, and enveloped the enemy in his own flames. The next step was to install a garrison among the conquered population, and to demolish the groves consecrated to their savage cults: for they considered it a duty to consult their deities by means of human entrails. — While he was thus occupied, the sudden revolt of the province was announced to Suetonius."

The cause of the revolt appears to have been ill-treatment by the Romans of the Iceni, especially by retired veterans. The colonia at Camulodunum and the towns of Londinium and Verulamium were sacked before Paulinus could bring his forces to bear on the situation. Only part of Legio XX took part, the rest still in post on the Welsh frontier for intervention by the Silures or Ordovices could have made a bad situation infinitely worse.

The probable course of events seems to have been roughly this:— Suetonius hurried ahead with his light troops, while the fourteenth legion and part of the twentieth followed by forced marches: the second had been summoned to join him, probably at Wroxeter (Viroconium), but its commander Poenius Postumus refused to leave his own front defenceless against the Silures of S. Wales. At London, the situation was found to be desperate, with the rebels in overwhelming force and the ninth legion virtually exterminated. Suetonius, therefore, fell back along the Watling Street until he met the legionaries, was forced to an engagement "somewhere in the Midlands" and only survived through being allowed to choose his own ground. Tacitus writes:

- "Suetonius had the fourteenth legion with the veterans of the twentieth, and auxiliaries from the neighbourhood, to the number of about ten thousand armed men, when he prepared to break off delay and fight a battle. He chose a position approached by a narrow defile, closed in at the rear by a forest, having first ascertained that there was not a soldier of the enemy except in his front, where an open plain extended without any danger from ambuscades. His legions were in close array; round them, the light-armed troops, and the cavalry in dense array on the wings. On the other side, the army of the Britons, with its masses of infantry and cavalry, was confidently exulting, a vaster host than ever had assembled, and so fierce in spirit that they actually brought with them, to witness the victory, their wives riding in waggons, which they had placed on the extreme border of the plain. Boudicea, with her daughters before her in a chariot, went up to tribe after tribe, protesting that it was indeed usual for Britons to fight under the leadership of women. "But now," she said, "it is not as a woman descended from noble ancestry, but as one of the people that I am avenging lost freedom, my scourged body, the outraged chastity of my daughters. Roman lust has gone so far that not our very persons, nor even age or virginity, are left unpolluted. But heaven is on the side of a righteous vengeance; a legion which dared to fight has perished; the rest are hiding themselves in their camp, or are thinking anxiously of flight. They will not sustain even the din and the shout of so many thousands, much less our charge and our blows. If you weigh well the strength of the armies, and the causes of the war, you will see that in this battle you must conquer or die. This is a woman's resolve; as for men, they may live and be slaves." Nor was Suetonius silent at such a crisis. Though he confided in the valour of his men, he yet mingled encouragements and entreaties to disdain the clamours and empty threats of the barbarians. "There," he said, "you see more women than warriors. Unwarlike, unarmed, they will give way the moment they have recognised that sword and that courage of their conquerors, which have so often routed them. Even among many legions, it is a few who really decide the battle, and it will enhance their glory that a small force should earn the renown of an entire army. Only close up the ranks, and having discharged your javelins, then with shields and swords continue the work of bloodshed and destruction, without a thought of plunder. When once the victory has been won, everything will be in your power." Such was the enthusiasm which followed the general's address, and so promptly did the veteran soldiery, with their long experience of battles, prepare for the hurling of the javelins, that it was with confidence in the result that Suetonius gave the signal of battle. At first, the legion kept its position, clinging to the narrow defile as a defence; when they had exhausted their missiles, which they discharged with unerring aim on the closely approaching foe, they rushed out in a wedge-like column. Similar was the onset of the auxiliaries, while the cavalry with extended lances broke through all who offered a strong resistance. The rest turned their back in flight, and flight proved difficult, because the surrounding waggons had blocked retreat. Our soldiers spared not to slay even the women, while the very beasts of burden, transfixed by the missiles, swelled the piles of bodies. Great glory, equal to that of our old victories, was won on that day. Some indeed say that there fell little less than eighty thousand of the Britons, with a loss to our soldiers of about four hundred, and only as many wounded. Boudicea put an end to her life by poison. Pœnius Postumus too, camp-prefect of the second legion, when he knew of the success of the men of the fourteenth and twentieth, feeling that he had cheated his legion out of like glory, and had contrary to all military usage disregarded the general's orders, threw himself on his sword."

The location of the battlefield is not known; most historians place it between Londinium and Viroconium (Wroxeter in Shropshire), on the Roman Road which the Romans called "Iter II" and is now known as "Watling Street" (much of the modern A5). The "Watling" name for the road originated in Anglo-Saxon times, thus the alternative modern name of the battle (Battle of Watling Street) is anachronistic and in the absence of evidence, speculative.

Civil War

Marcus Roscius Coelius (or Caelius) was the legate of the Legio XX in 68 AD. He was on bad terms with the provincial governor, Marcus Trebellius Maximus, and took the opportunity during the turmoil of the year of four emperors to foment mutiny against him. Trebellius lost all authority with the army, which sided with Coelius, and fled to the protection of Vitellius in Germania. Coelius and his fellow legates briefly ruled the province until Vitellius, now emperor, sent Marcus Vettius Bolanus to be the new governor in late 69. In 69 AD a vexillation was sent to support Vitellius in his brief term on the Imperial throne. Legio XX seems to have fought against its old comrades in Legio XIIII in the Battle of Cremona. The year of civil war ended when Vespasian took the Empire. Vespasian's renown came from his military success; he was legate of Legio II Augusta during the Roman invasion of Britain in 43. In 71 he recalled Coelius, whose treacherous behaviour had been made known to him, and replaced him as commander of Legio XX with Gnaeus Julius Agricola.

78/9 saw the transfer of Legio II Adiutrix from Lincoln to a new fortress at Chester.

Scotland

In 83 another vexillation participated in Emperor Domitian's war against the Chatti (see below for more on this), and the next year the legion was with Agricola's campaign into the far north of Britain. Legio XX may have resuced Legio IX, as Tacitus writes:

- "..they suddenly changed their plan, and with their whole force attacked by night the ninth Legion, as being the weakest, and cutting down the sentries, who were asleep or panic-stricken, they broke into the camp. And now the battle was raging within the camp itself, when Agricola, who had learnt from his scouts the enemy's line of march and had kept close on his track, ordered the most active soldiers of his cavalry and infantry to attack the rear of the assailants, while the entire army were shortly to raise a shout. Soon his standards glittered in the light of daybreak. A double peril thus alarmed the Britons, while the courage of the Romans revived; and feeling sure of safety, they now fought for glory. In their turn they rushed to the attack, and there was a furious conflict within the narrow passages of the gates till the enemy were routed. Both armies did their utmost, the one for the honour of having given aid, the other for that of not having needed support. Had not the flying enemy been sheltered by morasses and forests, this victory would have ended the war."

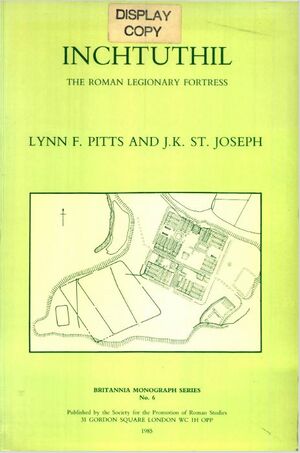

Legio XX was to have been based at Inchtuthil in Scotland, and began building a fortress there called Victoria: the northernmost Roman fortification in the Empire. Whilst the forts and fortlets along the northern frontier provided sufficient troops to deal with minor issues, the viability of the Roman occupation depended upon being able to surge a large and well equipped force to deal with major incursions. This requirement was met by the construction of Inchtuthil as a base for the Twentieth Legion, then consisting of over 5000 troops. The fortress was centrally located along the frontier enabling rapid reaction to any area as required.

But, in 84, before construction was completed, the decision was made to withdraw from the region. Inchtuthil had been occupied for around five years and seems to have been largely complete by the time it was abandoned; only the Praetorium (the Commanding Officer's House) and some of the accommodation for the Tribunes was incomplete. The speed of establishing the fortress is a testament to the efficiency, logistical prowess and industrial capability of the Roman military machine. In infrastructure terms the fortress was a town and for the Romans to establish it at this remote plain in the north of Scotland in just a matter of a few years is remarkable. The industrial achievement is perhaps best emphasised by the archaeological discovered in 1959 of a huge cache of Roman nails - in excess of 800,000 - ranging from small nails a few centimetres long to larger spikes used for the timber joints on the defensive arrangements. These were new, unused nails manufactured on the site presumably to support construction of the forts and watchtowers of the Glen Blocker and Gask Ridge systems. The weight of the nails was in excess of 10 tons almost certainly explaining why they were not taken south with the Legion. However, Iron was highly prized by the northern tribes - for its obvious weapon making properties - and so the nails were buried. The pit was elaborately concealed. The job could hardly have been more expertly done: the pit lay hidden for nearly 1900 years. After rediscovery, many of the nails were sent to museums as a gift and the rest of the hoard was sold to the public and other interested organisations with an offer of 5 shillings for an 8 to 10 inch nail and 25 shillings for a boxed set of 5 nails. Colville's (Iron and Steel refiners) who had been given the task of sorting and storing the nails state that all the complete nails had been "sorted gifted and sold" within 3 years of their discovery, ie. c.1963. Some of the almost 2000-year-old iron Inchtuthil nails have been used by atomic scientists to estimate the corrosion effects on barrels of nuclear waste.

The undoubtedly disgruntled legionaries completely demolished the fortress and moved back to the Welsh border (Wroxeter).

Chester

In the early 90s they moved into the fort of Deva (Chester), which Legio XX was to call "home" for the next two hundred years. See Roman Chester for more on this.

There was still much activity, however. The men of Legio XX helped build both Hadrian's Wall (starting in AD 122) and the Antonine Wall (c. 140). The first stage of building of Hadrian's Wall, the advance to the Antonine Wall and then the retreat back to Hadrian's Wall still present some mysteries. During the early reign of Hadrian (117-138), near contemporary historians (including Fronto) highlight that there was serious unrest in Roman-occupied Britain – unrest that broke out into full-scale revolt in c. 118 AD. Coin legends of 119–120 attest that Quintus Pompeius Falco was sent to restore order. In 122 Hadrian visited the island, and decreed numerous reforms for the province, which included the construction of the fortifications known as Hadrian's Wall. To implement them, however, the emperor replaced Falco with Aulus Platorius Nepos, and returned to Rome. It was at this eime that Legio VI Victrix: they would not only replace Legio IX at York but also work on the border defences with Legio XX.

The Roman empire reached its largest extent under Hadrian and the wall-building was a symptom of it having reached the limit of what could be held with the available resources. Hadrian preferred to invest in the development of stable, defensible borders and the unification of the empire's disparate peoples. This period of revolt in Britain is often associated with the supposed destruction of Legio IX Hispania (who were based at York) in about 120. However In 1959, a roof-tile dating to c. 125 AD was discovered at Nijmegen bearing the ownership mark of the Ninth Hispania. Later, further finds discovered nearby also bearing the Ninth’s stamp confirmed the presence of the Legion in lower-Germany around that time. It would therefore appear that Legio XX was involved in quelling the rebellion.

In the years between 155 and 158, a further widespread revolt occured in northern Britain, requiring heavy fighting by the British legions. Legio XX suffered severely, and reinforcements had to be brought in from the two Germanic provinces.

In 163 the order is given to abandon the Antonine Wall and for Roman troops to withdraw to Hadrian's Wall. Although the reasons are unclear, it is probable another uprising by the Brigantes forced the retreat.

Evidence from excavation at Chester shows that building work was relatively slow and at times appears to have ceased completely. many of the barrack blocks appear not to have been completed and possibly large parts of Legio XX were not in the fortress, and even not returning to the fortress as winter quarters outside of the campaigning season. In 175, a large force of Sarmatian cavalry, consisting of 5,500 men, arrived in Britannia, probably to reinforce troops fighting unrecorded uprisings - or possibly as a highly mobile force to deal with the stirrings of revolt amongst the troops and or provide scouting.

Revolts

In 196, governor Clodius Albinus of Britannia attempted to become emperor. The British legions were ferried to the continent, but were defeated by the lawful ruler Lucius Septimius Severus in the spring of 197. When the legions returned to their island, they found the province overrun by northern tribes. Punitive actions did not deter the tribesmen, and in 208, Severus came to Britain, in an attempt to conquer Scotland. He may have been defeated by malaria. One of the important reasons for this high incidence in tropical regions is the suitable climate and temperature, necessary for the development and survival of both mosquitoes as well as the parasite plasmodium. The current temperature in Scotland is too low for malaria-carrying insects to exist, but in Roman times a period of unusually warm weather in Europe and the North Atlantic ran from approximately AD 100 - 400.

A vexillation was sent to Germany in 255, and from there to the Danube and apparently never returned to Britain.

Under Caracalla (Severus' son - formally Marcus Aurelius Severus Antoninus Augustus), the unit added "Antoniniana" to its titles, but this was dropped about 222. Emperor Caracalla himself was the first person to wear an amulet bearing the word "abracadabra", although he never suffered from malaria. His father probably did. Caracala believed that the word possessed strong remedial properties and that it could protect the wearer of the amulet from various diseases, curses, and injuries. Its first use in written form occurred when Serenus Sammonicus, the personal physician to emperor Caracalla, mentioned it in his book Liber Medicinalis (“The Book on Medicine”). In chapter 51, Sammonicus suggested that those who suffered from malaria should wear amulets inscribed with the word “abracadabra” written in the shape of a triangle. According to the unreliable Augustan History Sammonicus was a famous physician and polymath, who was put to death with other friends of Geta in December 212, at a banquet to which he had been invited by Caracalla shortly after the emperor's assassination of his own brother

Emperor Trajan Decius (249-251) may have briefly added "Deciana" to the legion's name (but see below).

Aurelian (Latin: Lucius Domitius Aurelianus; 9 September c. 214 – c. November 275) supressed a further revolt. He was a Roman emperor who reigned from 270 to 275 during the Crisis of the Third Century. Postumus had declared himself emperor around 260 while defending the western empire from incursions by 'barbarian' tribes. He was recognised in Britain, Gaul and Spain - the so-called Gallic Empire - while the 'true' emperor Gallienus retained power in the remaining provinces Postumus was murdered by his soldiers in 268 but the Gallic Empire lasted until 274. Presumably Legio XX supported it.

As emperor, Aurelian won an unprecedented series of military victories which reunited the Roman Empire after it had nearly disintegrated under the pressure of barbarian invasions and internal revolts. He was murdered while waiting in Thrace to cross into Asia Minor. As an administrator, he had been strict and had handed out severe punishments to corrupt officials or soldiers. A secretary of his (called Eros by Zosimus) had told a lie on a minor issue. In fear of what the emperor might do, he forged a document listing the names of high officials marked by the emperor for execution and showed it to collaborators. The notarius Mucapor and other high-ranking officers of the Praetorian Guard, fearing punishment from the emperor, murdered him shortly after October 275. He is not known to have ever visited Britain, but did overcome the "Gallic Emperor" Tetricus, who was willing to abandon his throne and allow Gaul and Britain to return to the Empire, but could not openly submit to Aurelian. Instead, the two seem (according to some theories) to have conspired so that when the armies met at the Battle of Châlons at Durocatalaunum that autumn, Tetricus simply deserted to the Roman camp and Aurelian easily defeated the Gallic army facing him.

The End

The latest known reference to Legio XX is on coins struck by the usurper Carausius, who died in 294, in all, a unit history of nearly 350 years. Marcus Aurelius Mausaeus Valerius Carausius was a military commander of the Roman Empire in the 3rd century. He was a Menapian from Belgic Gaul, who usurped power in 286, during the Carausian Revolt, declaring himself emperor in Britain and northern Gaul (Imperium Britanniarum). He did this only 13 years after the Gallic Empire of the Batavian Postumus was ended in 273. He held power for seven years, fashioning the name "Emperor of the North" for himself, before being assassinated by his finance minister Allectus. Carausius appears to have appealed to native British dissatisfaction with Roman rule; he issued coins with legends such as "Restitutor Britanniae" (Restorer of Britain) and "Genius Britanniae" (Spirit of Britain). Some of these silver coins bear the legend "Expectate veni", (Come long-awaited one), recognised to allude to a messianic line in the Aeneid by the Augustan poet Virgil (the sixth and seventh lines of the Fourth Eclogue of Virgil), written more than 300 years previously. The Romans would stay in Britain for the next hundred years, but during this entire time there is no actual historical mention of Legio XX. Some historians have suggested that Legio XX was disbanded when Constantius Chlorus retook Britain in 296. In effect Legio XX had been "disloyal" from 260-274 and again from 286-296.

The usurper Magnentius may well have withdrawn much of the remaining forces from Britain following his revolt in 350 as the numbers of coin finds shows a decline for after 350. At the Battle of Mursa Major he lost almost 24,000 troops (of 36,000). Following the revolt of Magnentius and his defeat (AD 353), Paulus "Catena" was dispatched to Roman Britain in 353 by the paranoid Constantius II to exact savage reprisals against supporters of Magnentius in the army garrisons of Britain. Paulus was also probably a paranoid psychopath. Once he arrived, he widened his remit and began arresting other figures, often on apparently trumped-up charges and without evidence. So harsh were his measures that he earned the nickname Catena meaning 'The Chain'. Marcellinus (Book XIV, chapter 5) gives the following comments:

- Paulus had been promoted from being a steward of the emperor's table to a receivership in the provinces. Paulus, as I have already mentioned, had been nicknamed The Chain, because in weaving knots of calumnies he was invincible, scattering around foul poisons and destroying people by various means, as some skilful wrestlers are wont in their contests to catch hold of their antagonists by the heel.

Others have suggested that the name arose from his habit of dragging people through the streets in chains. Paulus' methods were so extreme and the injustices he committed so great, that the vicarius of Britain, Flavius Martinus, tried to persuade Paulus to release the innocent prisoners he had taken using the threat of his own resignation as leverage. Paulus refused and turned on Martinus, falsely accusing him and other senior officers in Britain of treason.

There is archaeological evidence of an investment of effort in the fortress at Chester and its facilities after 300. These works are on a scale which must have involved the military. At least half of the walls were rebuilt from the base up. Such a massive effort has been taken to suggest that Legio XX had been largely absent from Chester for much of the third century. Quite strangely many tombstones of soldiers were used in the rebuilding of the walls and one explanation may be that Legio XX was not the unit stationed at Chester at the time. After 350 building work outside the Roman walls seems to have ceased and it is thought that the entire civilian population may have moved into the fortress.

Legio XX In Fiction

Legio XX turns up in various works of fiction, many of which are of dubious historical accuracy. In truth, the situation in Britain had been desparate for some time. In the winter of 367, the Roman garrison on Hadrian's Wall rebelled, and allowed Picts from Caledonia to enter Britannia. Simultaneously, Attacotti, the Scotti from Hibernia, and Saxons from Germania landed in what might have been coordinated and pre-arranged[citation needed] waves on the island's mid-western and southeastern borders, respectively. Franks and Saxons also landed in northern Gaul. These warbands managed to overwhelm nearly all of the loyal Roman outposts and settlements. The entire western and northern areas of Britannia were overwhelmed, the cities sacked and the civilian Romano-British murdered, raped, or enslaved. Nectaridus, the comes maritime tractus (commanding general of the seacoast region), was killed (AD 367) and the Dux Britanniarum, Fullofaudes, was either besieged or captured in AD 369. The remaining loyal army units stayed garrisoned inside southeastern cities.

In the spring of 368, a relief force commanded by Flavius Theodosius (The Elder) gathered at Bononia (Boulogne-sur-Mer). It included four units, Batavi, Heruli, Iovii and Victores as well as his son, the later Emperor Theodosius I and probably the later usurper Magnus Maximus, his nephew. Theodosius took advantage of a break in the winter weather to cross the Channel to Richborough, leaving the rest of his troops at Bononia to await better weather. This enabled Theodosius to gather vital intelligence. He discovered that the British troops had either been overwhelmed, refused to fight or deserted; many also may not have been paid. By the end of the year, the barbarians had been driven back to their homelands; the mutineers had been executed; Hadrian's Wall was retaken; and order returned.

In 383, the Roman general then assigned to Britain, Magnus Maximus, launched his successful bid for imperial power, crossing to Gaul with his troops. He killed the Western Roman Emperor Gratian and ruled Gaul and Britain as Caesar (i.e., as a "sub-emperor" under Theodosius I). 383 is the last date for any evidence of a Roman presence in the north and west of Britain, perhaps excepting troop assignments at the tower on Holyhead Mountain in Anglesey and at western coastal posts such as Lancaster. These outposts may have lasted into the 390s, but they were a very minor presence, intended primarily to stop attacks and settlement by groups from Ireland. Coins dated later than 383 have been excavated along Hadrian's Wall, suggesting that troops were not stripped from it, as once thought or, if they were, they were quickly returned as soon as Maximus had won his victory in Gaul. In 388, Maximus led his army across the Alps into Italy in an attempt to claim the purple. The effort failed when he was defeated in Pannonia at the Battle of the Save (in modern Croatia) and at the Battle of Poetovio (at Ptuj in modern Slovenia). He was then executed by Theodosius.

Maximus does however turn up in local legends, in particular the legend of Saint Elen (Welsh: Elen Luyddog, lit. "Elen of the Hosts"), often anglicized as Helen of Caernarfon (to distinguish her from Helen of Constantinople), said to be a late 4th-century founder of churches in Wales. Traditionally, she is said to have been a daughter of the Romano-British ruler Eudaf Hen (Geoffrey of Monmouth calls him Octavius) and the wife of Macsen Wledig (Magnus Maximus). The legend has become a very garbled version of barely recognisible scraps of actual history mixed in with other myths.

With Maximus' death, Britain came back under the rule of Emperor Theodosius I until 392, when the usurper Eugenius would successfully bid for imperial power in the Western Roman Empire, surviving until 394 when he was defeated and killed by Theodosius. When Theodosius died in 395, his 10-year-old son Honorius succeeded him as Western Roman Emperor. The real power behind the throne, however, was Stilicho, the son-in-law of Theodosius' brother and the father-in-law of Honorius. Britain was suffering raids by the Scoti, Saxons, and Picts and, sometime between 396 and 398, Stilicho allegedly ordered a campaign against the Picts, likely a naval campaign intended to end their seaborne raids on the east coast of Britain. He may also have ordered campaigns against the Scoti and Saxons at the same time, but either way this would be the last Roman campaign in Britain of which there is any record. In 401 or 402 Stilicho faced wars with the Visigothic king Alaric and the Ostrogothic king Radagaisus. Needing military manpower, he posssibly stripped Hadrian's Wall of troops for the final time. 402 is the last date of any Roman coinage found in large numbers in Britain, suggesting either that Stilicho also stripped the remaining troops from Britain, or that the Empire could no longer afford to pay the troops who were still there.

Revolts continued Marcus (died 407) was a Roman usurper emperor (406–407) in Roman Britain. He was proclaimed Emperor by the army some time in 406. All that is known of his rule is that he did not please the army, and was soon killed by them and replaced with another short-lived usurper, Gratian who was acclaimed as emperor by the army in Britain in early 407. On the last day of December 406, an army of Vandals, Alans and Suebi (Sueves) had crossed the frozen Rhine. During 407, they spread across northern Gaul towards Boulogne, and Zosimus wrote that the troops in Britain feared an invasion across the English Channel. The army wanted to cross to Gaul and stop the barbarians but Gratian ordered them to remain. Unhappy with this, the troops killed him after a reign of four months and chose Constantine III as their leader. Constantine was a common soldier, but one of some ability. He marched on Rome, later retreated to Gaul, was besieged at Arles, captured and beheaded in 411. Roman rule never returned to Britain after the death of Constantine III. As the historian Procopius later explained, "from that time onwards it remained under [the rule] of tyrants".

Then came the Dark Ages. Many of the fictional works relating to Legio XX are set in the disturbed and poorly documented period at about the time that Roman control was failing.

The Cauldron

- Legio XX Valeria Victrix and their final days in Deva (Chester) in the early AD 400s form the backdrop to the Tom Stevens mythic fiction genre novel The Cauldron with the story's protagonist Valerian — the "Praefectus and Chief Centurion" — defending the city with the rump of the legion against the incursions of Hibernian pirates as the "Dark Ages" settle on Britannia. The movie Victrix! The Valiant of Albion is in production and features an adaptation of Stevens' novel. The blurb reads:

"Set in the twilight of the Roman Empire: the movie opens in 402 AD with the last gladiatorial games held in the amphitheatre at the Mega-Fortress of Deva in Britannia. Most of the elite Twentieth Legion Valeria Victrix 'The Valiant and Victorious' have been recalled to defend Rome from barbarians, with the rump left at the fortress city, commanded by Valerian 'The Valiant of Albion'. Defending the west coast of Britain from seaborne Hibernian invaders he's acutely aware that the empire is on the brink of collapse. The Hibernian raids are becoming more frequent, more intense and ever-more fierce. The spoilt wealthy Romans of the uber-rich villa-set, who occupy the Red Hills district on the coast, constantly pressure him for protection. Hopelessly overstretched: the remnant of the once mighty Twentieth-Legion will soon face their last and greatest challenge: as forces both natural and supernatural, led by the Pagan Warrior Goddess Morrigan, close-in to seize the original Holy Grail - the Celtic Cauldron of Rebirth in the epic final-drama of Rome's Empire in Britain."

Eagle in the Snow

- Legio XX Valeria Victrix was the legion featured in the novel Eagle in the Snow; author Wallace Breem postulates that they were annihilated by a Germanic invasion of 406. The blurb reads:

During the waning days of the Roman Empire, commander Maximus and his friend Quintus have been commanding the defence of Hadrian's Wall against the Picts and other tribes, who unite under the guidance of Maximus's archenemy, when the news of an impending Germanic invasion across the Rhine breaks. After being promoted to 'General of the West' and his wife's death, Maximus is sent to Moguntiacum (modern-day Mainz in Germany) where he is assigned to defend the entire 820-mile border between Gaul and Germania with just one legion, the XX.

A Dream of Eagles

- Several of the main characters in the early novels of Jack Whyte's A Dream of Eagles series were former members of Legio XX Valeria Victrix.

Medicus

- Gaius Petreius Ruso, protagonist of Medicus by Ruth Downie, is a military doctor in Britannia attached to Legio XX.

Operation Chaos

- Legio XX Valeria Victrix lends its name to the character Valeria Matuchek in Poul Anderson's Operation Chaos and its sequel Operation Luna; her mother is said to describe this legion as the last to leave Britain — "the last that stood against Chaos".

The Last of the Legions

- The first person narrator of Stephen Vincent Benét's short story "The Last of the Legions" is the senior centurion of the Valeria Victrix, who recounts the events and the impressions of soldiers and populace surrounding the departure of the legion from Britain.

Soldier of Rome

- Legio XX Valeria Victrix features in the six-novel series "Soldier of Rome: The Artorian Chronicles" by James Mace.

Through the Veil

- Legio XX Valeria Victrix is mentioned in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s short story "Through the Veil".

Meaning of "Valeria and Victrix"

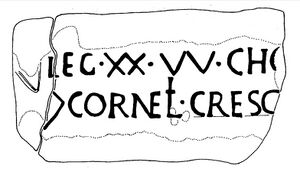

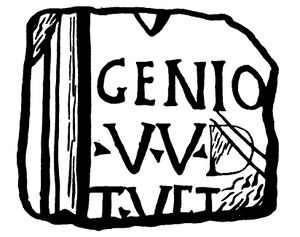

It is often said that the name of Legio XX is "Valeria Victrix" meaning "Valiant and Victorious". However, that might not be completely accurate. The passage from Dio ( c. 155 – c. 235) quoted above is the first mention of the "name" of Legio XX, and has been a source of some scholarly disagreement. Part of the problem arises due to scholars adding "VV" to the text of inscriptions when recording them, even if the original stone does not contain these letters.

Inscriptions which actually feature "VV"

Here are some examples of inscriptions which actually contain "VV":

- RIB 1430 - Hadrian's Wall;

- RIB 1645 - Hadrian's Wall;

- RIB 1093 - Hadrian's Wall;

- RIB 1708 - Hadrian's Wall

- RIB 2210 - Camelon fort;

- RIB 1020 - Cumbria (?);

- RIB 1166 - Hadrian's Wall;

- RIB 1204 - Hadrian's Wall;

- RIB 2184 - Antonine Wall;

The earliest which can be dated are from Gloucester (RIB 3069) and Carvoran (RIB 1826) and many are from Hadrian's Wall. Even RIB 3069 is problematic as the stone was recovered after re-use in the cathedral at Gloucester and the original context is not known. So there is only a single stone bearing the motto "Valeria Victrix" which can potentially be dated to Legio XX in Gloucester. The Roman legionary fortress of Burrium was founded on the River Usk by the military commander Aulus Didius Gallus, around AD 55. He moved his Legio XX into the area from its earlier base at Glevum (Gloucester). In AD 66, the legion was (possibly) transferred to Viroconium Cornoviorum (at Wroxeter) and their base in Wales was largely abandoned. The only evidence for Legio XX at Viroconium is a single tombstone (RIB 293 which does not use VV). "VV" is frequently used on tombstones of Legio XX at Chester, but it is difficult to date these other than to say that in general they come from the time after which Legio XX had moved to Chester.

...from Valerius Messalinus? (see: Legio XX Valeria Victrix)

One opinion holds that the honorific has two parts, one (Valeria) derived from the family (clan or gens) name of Valerius Messalinus, under whose command Legio XX gained distinction in suppressing the revolt of the Pannonians and Dalmatians in AD 6-9. This view was first put forward by Emil Ritterling in 1925.

Messallinus was born and raised in Rome. He was the oldest son of the famous senator, orator and literary patron Marcus Valerius Messalla Corvinus whom he resembled in character, from wife Calpurnia. Messallinus is known to have had at least one sister, Valeria, who married the Senator Titus Statilius Taurus. From his father’s second marriage, his younger paternal half-brother was the Senator Marcus Aurelius Cotta Maximus Messalinus. Messallinus was the great-uncle of Lollia Paulina, the third wife of Emperor Caligula, and a relation to Statilia Messalina, the third wife of Emperor Nero. In AD 6, Messallinus served as a governor in Illyricum. During his time in Illyricum, he served with Tiberius with distinction in a campaign against the Pannonians and Dalmatians in the uprising of the Great Illyrian Revolt (Bellum Batonianum) with the half-strength Legio XX. In one battle the legion cut through the enemy lines, was surrounded, and cut its way out again. Messallinus defeated the Pannonii, led by Bato the Daesitiate, and prevented spread of the uprising. For his defeat over Bato, Messallinus was rewarded with a triumphal decoration (ornamenta triumphalia) and a place in the procession during Tiberius’ Pannonian triumph in AD 12, four years after the death of his father. Tacitus notes that Messallinus, along with Caecina Severus, proposed a golden statue be placed in the temple of Mars the Avenger (Mars Ultor), and an altar dedicated to Vengeance, in celebration of the execution/suicide of Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso - who may have murdered Germanicus.

McPake argues against the notion that Legio XX acquired its title in honor of its commander. It would have been the only legion to have done so and, presumably, its honorific would have appeared on at least one other inscription in the more than half a century that followed. Yet, of all those that mention the Twentieth Legion, there is no epigraphic evidence datable before AD 60 that shows any indication of the name. Only in inscriptions from the late first century AD do the initial letters VV or Val Vic begin to appear. However a number of unusual privileges did attach to this family, including the right to burial within the city walls, and a special place for its members in the Circus Maximus, where the unique honour of a throne was granted them. The house built by Publius Valerius Publicola at the foot of the Velian Hill was the only one whose doors were permitted to open into the street. The historian Niebuhr conjectured that, during the transition from the monarchy to the Republic, the Valerii were entitled to exercise royal power on behalf of the Titienses, one of the three Romulean tribes that made up the Roman people.

...from "Valeria" (valiant)? (see:Legio XX Valeria Victrix)

McPake contends, Valeria is derived from valeo (which the Oxford Latin Dictionary defines as “to possess, or have predominance in, military or political power, resources, etc.”) and personifies its qualities of strength and well-being, luck and good omen, in much the same way that Martia represents the warlike qualities of Mars. Nor was Legio XX the only military unit to hold this title. Cohors I Breucorum also was known as Valeria Victrix (in german), which must have been given that title quite independently of a commander called Valerius or events in Britain. Cohors Breucorum was an important Roman castrum located in western Mauretania Caesariensis (located at Takhemaret in what is now Algeria). Curiously, the name was given because it was under the control of the Cohors of the "Breuci", a tribe from ancient Illyria, where the abovementioned revolt took place. An example of the use of VV by the Cohors I Breucorum (from a stone near Ingolstadt) can be found in EDCS;

...from "Victorious Black Eagle"? (see; Legio XX Valeria Victrix)

Incidentally, the cap-badge of the Mercian Regiment, formed by amalgamation including the Cheshire Regiment is derived from the double-headed eagle used as a personal emblem by Leofric, Earl of Chester (see: Dark Ages) and that this could this be a corntinuous tradition from the Roman eagle, through the Mercian Eagle to the eagle of the regiment (this also featured as a pub sign in Castle Street).

This may be a based on a mistranslation of Pliny the Elder’s Natural History (10.3 ‘melanaetos a Graecis dicta, eadem in valeria’). Pliny's source was Aristotle's Historia animalium (9, chapter 32) which might be read as "hare-eagle" (leporaria). Unfortunately early editions of english translations of Pliny contained the error:

- "The one cailed by the Greeks the black eagle, and also the hare-eagle, is smallest in size and of outstanding strength ; it is of a blackish colour. It is the only eagle that rears its own young, whereas all the others, as we shall describe, drive tliem away; and it is the only one that has no scream or cry."

and this led some to believe that "Valeria" meant black eagle. Later translations make it clear that Aristotle calls it "the hare-killing eagle". It is not at all clear which type of eagle Aristotle is referring to. The smallest eagle is the Booted eagle which breeds in southern Europe, North Africa and across Asia, but it is not "black". There are two relatively distinct plumage forms. Pale birds are mainly light grey with a darker head and flight feathers. The other form has mid-brown plumage with dark grey flight feathers. It hunts small mammals, reptiles and (mainly) smaller birds.

...after the Boudican revolt?

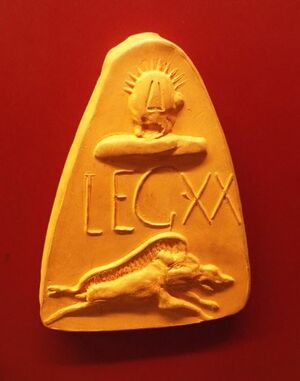

Probably the best-known event in the history of Legio XX is the defeat of Boudicca's Revolt in 60. The Roman governor Suetonius Paulinus was just completing the eradication of a Druid stronghold in northwest Wales (Angelsey) when he got word of the revolt. The rebels had sacked and burned three undefended towns, including London, and had ambushed and wiped out part of Legio IX Hispana, which had been rushing to the scene (although the Roman cavalry contingent escaped cleanly--some ambush!). Paulinus force-marched his army - Legio XIIII Gemina, much of Legio XX, ans some auxiliaries - across the province, and met Boudicca's vastly larger force head on. In the resulting battle, the Britons were completely crushed, and Roman losses were minimal.