Database changes have finished applying - please report any issues you're (still) seeing to support@shoutwiki.com.

Viking

Many earlier guidebooks to Chester give scant mention (if they include it at all) to the Scandinavian settlement in the Wirral, often merely stating that the Norse, under the leadsership of Ingimund, were allowed to settle in Mercian territory by permission of Æthelflæd who effectively ruled Mercia from 911 until her death in 918. There is, however, much more to the story of "Viking Chester".

Viking Chester

"Vikings" were the seafaring Norse people from southern Scandinavia (in present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden) who from the late 8th to late 11th centuries pirated, raided and traded from their Northern European homelands across wide areas of Europe, and explored westward to Iceland, Greenland, and Vinland. The term "Viking" is a historical revival; it was not used in Middle English, some sources state that it was revived from Old Norse "vikingr" meaning "freebooter, sea-rover, pirate", which usually is explained as meaning properly "one who came from the fjords," from "vik" meaning "creek, inlet, small bay" (cf. Old English "wic", Middle High German "wich" "bay," and second element in Reykjavik). Other sources note that Old English "wicing" and Old Frisian "wizing" are almost 300 years older, and probably derive from wic "village, camp" (temporary camps were a feature of the Viking raids), related to Latin vicus "village, habitation".

In modern English and other vernaculars, the term Viking also commonly includes the inhabitants of Norse home communities during this period. This period of Nordic military, mercantile and demographic expansion had a profound impact on the early medieval history of Scandinavia, the British Isles, France, Estonia, Kievan Rus' and Sicily. The Vikings were known as Ascomanni ("ashmen") by the Germans for the ash wood of their boats, Dubgail and Finngail ("dark and fair foreigners") by the Irish, Lochlannach ("lake person") by the Gaels and Dene (Dane) by the Anglo-Saxons. Geographically, the Viking Age covered Scandinavian lands (modern Denmark, Norway and Sweden), as well as territories under North Germanic dominance, mainly the Danelaw, including Scandinavian York, the administrative centre of the remains of the Kingdom of Northumbria, significant parts of Mercia, and East Anglia.

Expert sailors and navigators aboard their characteristic longships, Vikings voyaged as far as the Mediterranean littoral, North Africa, and the Middle East. After decades of exploration, piracy and plundering around the coasts and rivers of Europe, Vikings established Norse communities and governments scattered across north-western Europe, Belarus, Ukraine and European Russia, the North Atlantic islands all the way to the north-eastern coast of North America. The Vikings and their descendants established themselves as rulers and nobility in many areas of Europe. The Normans, descendants of Vikings who conquered and gave their name to what is now Normandy, also formed the aristocracy of England after the Norman conquest of England.

The Vikings not only raided parts of Cheshire and the Wirral but also settled there. In addition much of the history of the region and the city of Chester in the late ninth to late eleventh centuries had a Viking aspect. This article looks briefly at the evidence for a Viking presence, some historical background before the start of the "Viking Age" and then a detailed consideration of the interaction, both direct and indirect between the City and the Vikings.

The Evidence

The presence of a Viking settlement in the Wirral and their influence at Chester first became evident to historians from place names and has more recently been confirmed by DNA studies. There is additional evidence in the form of church dedications and physical objects.

Place Names

Evidence of Norse settlement in Wirral can be seen from its place names, such as the '-by' (meaning "village" in Scandinavian languages) suffix, which is common in the area i.e, Helsby - hjalli-byr village at the ledge (or "village with a rack to dry fish"), Raby, from the Old Norse ra-byr meaning boundary or border settlement, Frankby (Franki's settlement), Greasby (wooded stronghold). Tranmere comes from trani melr ("cranebird sandbank"), Meols derives from the Old Norse for sandbanks or sandhills. West Kirby, or West Church Settlement - the settlement of Vestri Kirkjubaer in Iceland has exactly the same name, which translates from Icelandic as West Kirby. Thor’s Stone , also known as Thor’s Rock, on Thurstaston Common, a large red sandstone outcrop of unusual shape and appearance, is a place shrouded in legend. Early Viking settlers are purported to have held religious ceremonies there in honour of the thunder god Thor, or used it as a place to hold meetings.

Some of this legend is apparently quite recent. As Gavin Chappell notes:

- Writing in Notes & Queries in November 1877, local worthy Sir James Picton brought to the attention of the general populace the ‘Great Stone of Thor’ a ‘very interesting relic of Saxon or Danish heathendom.’ Stating that there was no local legend about it, and that local historians did not mention it, he linked the rock with the township in which it was located, suggesting that it was ‘Thor’s Stone,’ and that the name Thurstaston came from Thors-stane-tun, or the town of Thor’s Stone. His real agenda was to stop the encroachment of developers in the area, and the article is directly responsible for Thurstaston Common becoming a public park rather than a Victorian housing development. Regardless of this, the story grew and grew. The associations between Thor’s Stone and pre-Christian religion were such that in the late nineteen eighties, members of an organisation called the Hearth of the Sons of Odin provoked a minor furore when they ‘reclaimed’ the rock for the worship of Thor and other Norse gods. .. The Journal of the British Archaeological Association, Vol. XLIV, printed in 1888, included an article describing a trip made by its members to Wirral, during which they visited ‘the Thor Stone’ where Picton himself regaled them with its supposed history. Again, he maintained that no legend was associated with the area (clearly unaware that he had invented one)

Further examples include Heskeths field (which derives from hestaskeið = horse race track), Storeton is old Norse for great farmstead or farmstead by a young wood. Claughton means hamlet on a hillock, Neston (farmstead at the promontory), Hinderton (village lying at the back), Arrowe (shieling or hill pasture), Denhall (Danes' well), Gayton (goat farmstead) and Ness (promontory, an almost lost feature of the original coastline).

Some care is needed with place names, as Old Norse (ON) and Old English (OE) are not dissimilar languages and OE adopted ON "loanwords". Professor Steve Harding, who did much to popularise the history of "Viking Wirral", list a very large number of places in the Wirral with supposed Viking names. Many of these cannot be disputed, but some could be derived from Old English. For example, the word "dale" comes from the Old English word "dael", from which the word "dell" is also derived. It is also related to Old Norse word "dalr" (and the modern Icelandic word "dalur"), which may perhaps have influenced its survival in northern England. The Germanic origin is assumed to be "dala-". "Dal-" in various combinations is common in placenames in Norway. "Dibbinsdale" is sometimes said to have marked the boundary of the area of Norse-speaking settlement, and so might be thought to be an example of a "Viking" place name, but it only appears to have been in use since 1831. However, the presence of a high concentration of places with the "-by" ending does provide convincing evidence of a strong Viking/Norse presence.

St Olave and St Bridget

Chester has at least one and possibly two ancient churches with a Norse connection. Other dedications with possible Viking related originas are found in the surrounding area.

Olaf II Haraldsson (Óláfr Haraldsson c. 995 – 29 July 1030), later known as St. Olaf (and traditionally as St. Olave), was King of Norway from 1015 to 1028, but spent his earlier years as a pillaging Viking. Son of Harald Grenske, a petty king in Vestfold, Norway, he was posthumously given the title Rex Perpetuus Norvegiae (English: Eternal/Perpetual King of Norway) and canonised at Nidaros (Trondheim) by Bishop Grimkell, one year after his death in the Battle of Stiklestad on 29 July 1030. His remains were enshrined in Nidaros Cathedral, built over his burial site. His sainthood encouraged the widespread adoption of Christianity by Scandinavia's Vikings/Norsemen. He is the St Olave of the now redundant church in Lower Bridge Street.

In life, Olaf was more of a psychopath than a saint. He took part in the Viking invasion of England in 1009. One account (which may not be strictly accurate) describes the excessively violent conduct of the raiders/invaders and eventual murder of archbishop Ælfheah as follows:

- "Olav attacked it in 1011. One English chronicler left this description of when the city was sacked: “some of the inhabitants were run through, others burned alive in their own houses, women were dragged by their hair down the streets and burned alive; babies were crushed under heavy wagon wheels.” When the Vikings left Canterbury, they took with them not only a gigantic tribute, but also the archbishop Ælfheah. During a drinking-bout the Vikings entertained themselves by throwing “stones, bones and oxen skulls” at their venerable prisoner, until one of them was deeply moved by some sort of compassion, ending the misery of man of God by splitting his head with an axe."

Pope Gregory VII canonised Ælfheah in 1078, with a feast day of 19 April. Pope Alexander III confirmed Olaf's local canonisation in 1164 with a feast day of 29 July. In the bull Non parum animus noster, in 1171 or 1172, Alexander III gave papal sanction to ongoing crusades against pagans in northern Europe, promising remission of sin for those who fought there. In doing so, he legitimized the widespread use of forced conversion as a tactic by those fighting in the Baltic.

The presence of a church with a "Viking" dedication provides good evidence of a sizable Scandinavian presence in Chester. There is also the church of St Bridget which could well be earlier. The dedication was especially likely to have been favoured by immigrants from Ireland and was used also at West Kirby, in the Scandinavian settlement on Wirral. Moreover, since the medieval parish of St. Bridget's at Chester was in two portions, separated by parts of other parishes, it was perhaps once larger and had been eroded by later foundations. St Bridget was probably the first to serve the Hiberno-Norse in Chester and dated from the period of their settlement in the city.

DNA

Recent Y-DNA research has also revealed the genetic trail left by Vikings in the Wirral, specifically relatively high rates of the Haplogroup R1a, which is distributed in a large region in Eurasia, extending from Scandinavia and Central Europe to southern Siberia and South Asia. It is associated in Britain with Norse ancestry. Y-chromosome DNA is only passed down the male line. Similar studies on the famale ancestry line are done with mitochondrial DNA (on which Wikipedia needs a better article).

"Viking DNA: The Wirral and West Lancashire Project" is the culmination of several years of research by Wirral-raised Professor Steve Harding from the University of Nottingham, Professor Mark Jobling and Dr Turi King from the University of Leicester. A group of volunteers were selected according to certain areas and specific surnames present in these areas at least prior to 1600. DNA tests on around 100 men from the area who had local surnames dating back hundreds of years. Some names were sourced from a tax register from the time of Henry VIII, others from lists of alehouse and criminal records, and a list of people who contributed to the stipend of a priest. Scientists found two men from Meols who shared identical historical links to Scandinavia during DNA studies, their strongest DNA link was to Gotland, an island off the east coast of Sweden.

Overall, approximately 50% of the DNA admixture of the old population of Wirral, and also the old population of West Lancashire appears to be Norse-Scandinavian in origin.

Physical Evidence

The presence of isolated finds of "Viking" artifacts does not always indicate invasion or settlement, but could be an item lost by a traveller or trader passing through an area. However larger physical objects, such as grave markers and the remains of buildings are more likely to indicate a permanent presence.

In the museum in the old school-house by the churchyard at West Kirby one may see a stone, which, from its shape, antiquaries call a 'hog-back'. The hog-back is generally believed to be a tombstone or grave-slab that marked the burial-place of some Scandinavian chief, although hogbacks are not found in Scandinavia. They are considered a unique invention made by the Viking settlers in Northern England. The hog-back stone bears heavy damage on its top surface and there has been speculation that it has lost short parts of both of its ends (which possibly included "end-beasts" - although not all do). The decoration consists of three bands; wheel and bar ornament on side A’s top, skeuomorphic shingle-roof tegulae (tiles) in the middle and plaitwork beneath. This stone, said to date from the 10th century AD was discovered during the restoration of the church in 1869. It has been suggested that the monument type was invented in the late 9th century, at a time when Viking warlords had seized power at York. However, a tenth-century date has been generally accepted due to the ornament on hogbacks, largely influenced by the Borre and Jellinge styles which appeared in Scandinavia in the late ninth and early tenth centuries.

The West Kirby stone presents something of a puzzle as it is not of the local rock but appears to be from the Cefn quarries near Ruabon/Wrexham. This was a much sought-after building stone for centuries, but the quarries are well outside the Hiberno-Norse sphere of influence. The Pillar of Eliseg is from the same hard, grey, quartz-rich sandstone, as is the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct over the River Dee. Despite that some earlier hogbacks have pagan imagery, the fact that they are typically found in churchyards may indicate that they were made for wealthy Christian Scandinavians. The puzzle is further complicated by looking at the distribution of hog-backs through England and Wales - this type of monument is rare outside of the north-east, with only a few elsewhere. The majority of the stones appear to come from areas which were not settled by what might be called "Ingamund's People". However, the coincidence of hogback distribution with that of Norse-Irish place-names in Northern England allows for the possibility of ultimate Irish influence. Tegulated house-shaped caps are common on tenth-century high crosses in Ireland. The earliest forms of hog-back are found in the Allertonshire area of North Yorkshire, those from Brompton being well executed copies of long houses with "bombe" sides and large-muzzled bears as end-beasts, each occupying a third of the monument. Houses of this type have been revealed in an eleventh-century context in England, though not in Yorkshire as yet, and Scandinavian sites, notably the Danish forts of Trelleborg and Fyrkat, have yielded ground plans of very similar buildings. Curiously, recent excavations at Hilbre Island may have revealed a similar structure.

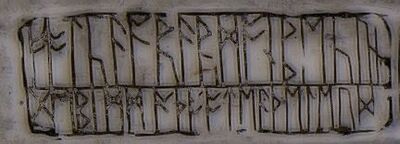

The history of the Wirral during this period is made even more complicated by finds at Overchurch. These include the Overchurch runestone, which may date from the period or slightly earlier (9th century) and the very extensive stone circle(s) at Overchurch and Arrowe of which little trace remains except for the placement of stones indicated on early OS maps. The co-location of the runestone - the only one known from Cheshire - and the neolithic circles at the very same site seems like a remarkable co-incidence, and there may be a link that is yet to be discovered (See: Gawain for more on this).

There is evidence from Chester for at least trade contact with the Isle of Man. Chester has yielded several ring-headed pins of a Hiberno-Norse type very like examples found in Man, and fragments of jewellery from a hoard deposited at Castle Esplanade c. 965 have also been interpreted as similar to material from a hoard found on the island. More permanent settlement exists in the form of the remains of Norse-type buildings. Huts excavated in Lower Bridge Street have been interpreted as of the bow-sided type especially associated with Scandinavian sites in England, and what was perhaps the name of a gate in the City Walls in that quarter, Clippe Gate, may have derived from the Old Norse personal name "Klippr".

"Scouse"

One rather amusing piece of evidence comes from culinary habits.

Lapskaus is a thick Norwegian stew made of meat and potatoes. In Britain such a dish and its variants are known in areas which were settled by the Vikings. "Lobscouse", a European sailors' stew or hash is particularly associated with Liverpool. Similar dishes include the Danish "labskovs", Finnish "Lapskoussi" or the German "labskaus". Latvian "Labs kauss", is generally taken to mean "good bowl" or hotpot, Lithuanian "labas káušas", means the same. Many other origins for the culinary term "scouse" have been suggested.

It has been proposed that the presence of this dish arrived in all these places through the agency of sailors - the "Oxford Companion to Food" states that lobscouse:

- "almost certainly has its origins in the Baltic ports, especially those of Germany"

Potatoes and salted meats were a standard fare of sailors and Labskaus would make a "less than fresh" cut of meat more palatable and stretch the meat supply. In many modern recipes the meat is salted and set aside for a few days to effect a brief "cure". Obviously, the potato would not have been known to the Vikings (they were introduced to Europe from the mid-Americas in the second half of the 16th century by the Spanish). Very few root vegetables were known at the time (possibly only the parsnip). An alternative meaning of the name of the dish could be derived from "wrapped in a blanket", which would suggest that the salted meat was wrapped in cloth and soaked in the sea to remove the preservative salt and possibly even cooked by boiling the package in sea water.

The History

The political history of human migration and settlement has been the subject of much debate. Views on population movements range from invasion and "ethnic cleasing" with wholesale eradication of any "indigenous" population, to replacement of the controlling classes by new rulers and artisans with inter-breeding into the previous society. Future archaeologists may well find the remains of Japanese cars in Chester, but this does not mean that the City was invaded by the Japanese. Similar arguments may be applied to earlier cultures, where technology such as the replacement of bronze with iron need not always mean that there were "Iron Age invaders". The Romans invaded Britain, as did the Normans, but neither replaced the existing population with "Italians" or "French". The impact of the Vikings on the history of Chester is best seen against the background of previous events.

Anglo-Saxons

The Anglo-Saxons were a cultural group who inhabited England from the 5th century. They comprised people from Germanic tribes who migrated to the island from continental Europe, their descendants, and indigenous British groups who adopted many aspects of Anglo-Saxon culture and language. The Anglo-Saxons established the Kingdom of England, and the modern English language owes almost half of its words – including the most common words of everyday speech – to their language. The Old English ethnonym "Angul-Seaxan" comes from the Latin Angli-Saxones and became the name of the peoples Bede calls Angli and Gildas calls Saxones. Anglo-Saxon is a term that was rarely used by Anglo-Saxons themselves. It is likely they identified as ængli, Seaxe or, more probably, a local or tribal name such as Mierce, Cantie, Gewisse, Westseaxe, or Norþanhymbre. Scholars have not reached a consensus on the number of migrants who entered Britain in this period. The invasion and settlement was not unopposed - see: Mold Cope.

Mercia

Archaeological surveys show that Angles settled the lands north of the River Thames by the 6th century. The Mercian kings were the only Anglo-Saxon ruling house known to claim a direct family link with a pre-migration Continental Germanic monarchy, via Icel supposedly the son of Eomer (443-489), last King of the Angles in Angeln. Icel supposedly led his people across the North Sea to Britain around 515. Eomer would later give his name to a major character in "Lord of the Rings".

In many ways Mercia was the dominant English kingdom for three centuries, between about 600 and about 900. In much later medieval times, historians would begin to refer to the early Anglo-Saxon kingdoms as the "Heptarchy", listing its members as East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Mercia, Northumbria, Sussex, and Wessex. Although heptarchy suggests the existence of seven kingdoms, the term is just used as a label of convenience and does not imply the existence of a clear-cut or stable group of seven kingdoms at all times. The number of kingdoms and sub-kingdoms fluctuated rapidly as kings contended for supremacy. In the late 6th century, the king of Kent was a prominent lord in the south. In the 7th century, the rulers of Northumbria and Wessex were powerful. In the 8th century, Mercia achieved hegemony over the other surviving kingdoms, particularly during the reign of Offa (of dyke fame). Mercia was a perculiar state in that it does not appear for much of its existence to have had a capital as such, but made use of a "portable court" with the ruler moving from place to place and perhaps over-wintering at a royal estate.

Victorian historians sometimes imply that Mercia was effectively destroyed by the Vikings, but this is now not believed to be the case. The Viking raiders and later invaders were relatively few in number and would replace the Mercian aristocracy rather than wipe out the population. As with the later Norman Conquest there would be a significant fusion of Viking and Mercian cultures.

Viking Origins

Scandinavia was among the last regions of Europe that became habitable after the ice age, when glaciers gave way to the land 10,000 years ago. The Roman writer Tacitus (about 98 AD) described a nation called "Suiones" living "on an island in the Ocean". These Suiones had ships that were peculiar because they had a prow in both ends (as on typical "Viking" ships). This word Suiones is the same name as in Anglo-Saxon Sweon whose country in Angle-Saxon was called Sweoland (Svealand) - now called Sweden. The ship has been functioning as the centerpiece of Scandinavian culture for millennia, serving both pragmatic and religious purposes, and its importance was already deeply rooted in the Scandinavian culture when the Viking Age began. Scandinavia is a region with relatively high inland mountain ranges, dense forests and easy access to the sea with many natural ports. Consequently, trade routes were primarily operated via shipping, as inland travel was both more hazardous and cumbersome.

The Vikings built many different kinds of craft, from small fishing boats and ferries, to their famous longships. Viking boats were advanced in terms of shipping technology and far surpassed contemporary English or Frankish vessels in lightness and efficiency. The secret of the Viking ship lay in its unique construction. Using a broad ax rather than a saw, expert woodworkers would first split oak (in Denmark) or pine (in Norway and Sweden) tree trunks into long, thin planks. They then fastened the boards with iron nails to a single sturdy keel and then to each other, one plank overlapping the next. The Vikings gave shape to the hull using this "clinker" (or "lapstrake") technique rather than the more conventional method of first building an inner skeleton for the hull and then forming a shell of close-fitted planking. The ships were made watertight by filling the spaces between the planks with wool, moss or animal hair, mixed with pine tar or tallow. The ships were all the same long narrow shape, with shallow draughts. This meant that they could be used in shallow water along shelving coastlines and quite far up rivers. They could be landed on a beach and many appear to have had a false keel forward to protect the fore-parts of the ship in such circumstances. Longships were double-ended, the symmetrical bow and stern allowing the ship to reverse direction quickly without a turn around; this trait may have proved particularly useful at northern latitudes, where icebergs and sea ice posed hazards to navigation.

Products that the Vikings exported from Scandinavia included walrus ivory, whalebone, and the furs and skins of animals such as fox, bear, beaver and otter. They also carried amber, a fossilized resin that was cut and polished to make beads, pendants and brooches. A significant amount of amber was used in the "Mold Cope" which dates from about 1900-1600 BC. This is believed to have been associated with the society who mined copper in North Wales and possibly indicates trade with Scandinavia at that early date.

"First" raids

The exact reasons for Vikings venturing out from their homeland are uncertain; some have suggested it was due to overpopulation of their homeland, but the earliest Vikings were looking for riches, not land. This was also notably a time of quite extreme climate variation in the North Atlantic region, with the Vikings being able to colonise a forested southern Greenland in around 985. Climate variations on this scale are likely to lead to changes in agriculture and the location of fishing grounds, all of which might lead to population changes and movements. At the time, England, Wales, and Ireland were vulnerable to attack, being divided into many different warring kingdoms in a state of internal disarray. One interesting possibity is that in 774/5 the Earth suffered a "Miyake Event" which is a rare, but massive, solar storm. This would particularly affect high nothern latitudes, and could produce some radiation damage as well as spectacular auroral effects. Such atmospheric effects were recorded by chronicles:

- "Annus Domini (the year of the Lord) 774. This year the Northumbrians banished their king, Alred, from York at Easter-tide; and chose Ethelred, the son of Mull, for their lord, who reigned four winters. This year also appeared in the heavens a red crucifix, after sunset; the Mercians and the men of Kent fought at Otford; and wonderful serpents were seen in the land of the South-Saxons."

It is possible that the consequences of the event had effects on Viking society, possibly causing crop losses and both human and livestock sickness, which led to the onset of raids. Initially, the Vikings limited their attacks to sea-based "hit-and-run" raids: if they could get in and out quickly then they would face little local defence and would be safe from any organised reprisal. A notable early raid being that of 793 at Lindisfarne. The chronicles associate the attack with atmospheric portents similar to those of a just a few years below. The D and E versions of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle record:

- "Her wæron reðe forebecna cumene ofer Norðhymbra land, ⁊ þæt folc earmlic bregdon, þæt wæron ormete þodenas ⁊ ligrescas, ⁊ fyrenne dracan wæron gesewene on þam lifte fleogende. Þam tacnum sona fyligde mycel hunger, ⁊ litel æfter þam, þæs ilcan geares on .vi. Idus Ianuarii, earmlice hæþenra manna hergunc adilegode Godes cyrican in Lindisfarnaee þurh hreaflac ⁊ mansliht." (In this year fierce, foreboding omens came over the land of the Northumbrians, and the wretched people shook; there were excessive whirlwinds, lightning, and fiery dragons were seen flying in the sky. These signs were followed by great famine, and a little after those, that same year on 6th ides of January, the ravaging of wretched heathen men destroyed God's church at Lindisfarne.)

Once again, the reference to "Dragons" could be a reference to auroral displays, and there is a reference to a famine following in their wake. It is possible that the famine was not simply a local one, but that there were similar supply disturbances in Scandinavia. The generally accepted date for the Viking raid on Lindisfarne is on or before 8 June; Michael Swanton writes: "vi id Ianr, presumably [is] an error for vi id Iun (8 June) which is the date given by the Annals of Lindisfarne, when better sailing weather would favour coastal raids. The assault on Lindisfarne was not the first raid, as records indicate raids going back to 787/9. However it was an attack on one of the most famous places in the Christian world and a shocked Alcuin of York wrote io Ethelred King of Northumbria:

- "Lo, it is nearly 350 years that we and our fathers have inhabited this most lovely land, and never before has such terror appeared in Britain as we have now suffered from a pagan race, nor was it thought that such an inroad from the sea could be made. Behold the church of St Cuthbert spattered with the blood of the priests of God, despoiled of all its ornaments; a place more venerable than all in Britain is given as a prey to pagan peoples .."

These preliminary raids, unsettling as they were, were not followed up in any consistent way. However, the Vikings soon expanded their operations elsewhere. In the years 814-820, Danish Vikings repeatedly sacked the regions of Northwestern France via the Seine River and also repeatedly sacked monasteries in the Bay of Biscay via the Loire River. Eventually, the Vikings settled in these areas and turned to farming. This was mainly due to Rollo, a Viking leader who seized what is now Normandy in 879, and formally in 911 when Charles the Simple of West Francia "granted" him the Lower Seine which were already under Viking control. The Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte of 911 effectively created the Duchy of Normandy. The Vikings were granted all the land between the river Epte and the sea, as well as Duchy of Brittany, which at the time was an independent country which West Francia had unsuccessfully tried to conquer. Rollo also agreed to be baptised and to marry Charles' daughter Gisela. here is no evidence that Rollo owed any service or oath to the king for his lands, nor that there were any legal means for the king to take them back: they were granted outright. Rollo's Vikings would later develop into the Normans, a society with significant military power and prowess: and one which would have a significant influence on English history.

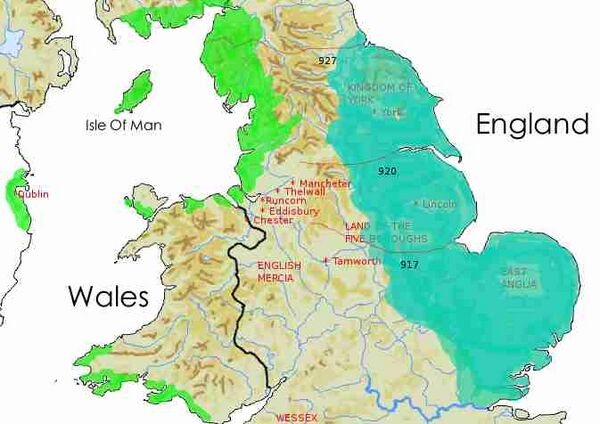

Alfred the Great

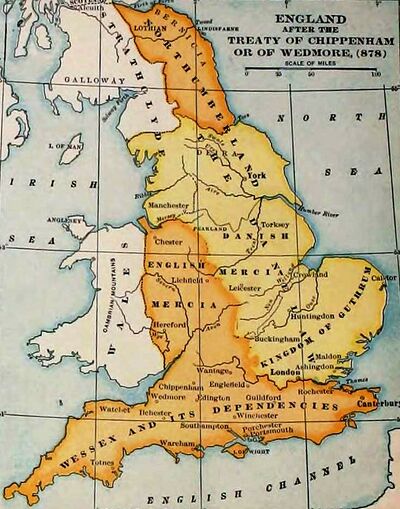

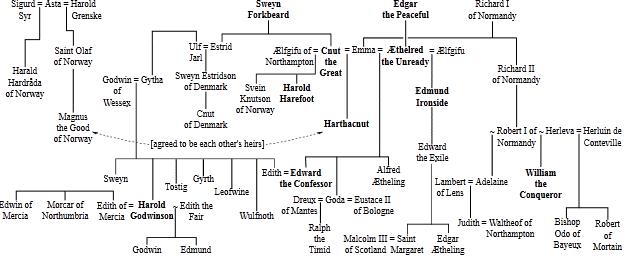

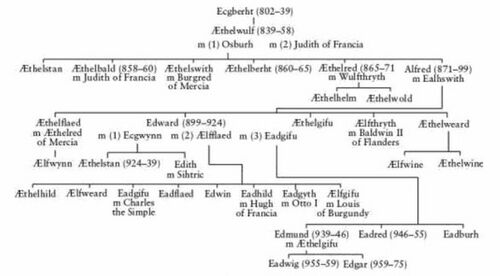

Alfred the Great (848/9 – 26 October 899) was king of Wessex from 871 to c. 886 and king of the Anglo-Saxons from c. 886 to 899. He may never have expected to be king as he was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf of Wessex. His father died when he was young, and three of Alfred's brothers, Æthelbald, Æthelberht and Æthelred, reigned in turn before him. After ascending the throne, Alfred spent several years fighting Viking invasions. He won a decisive victory in the Battle of Edington in 878 and made an agreement with the Vikings, creating what was known as the Danelaw in the North of England. Alfred also oversaw the conversion of Viking leader Guthrum to Christianity. He defended his kingdom against the Viking attempt at conquest, becoming the dominant ruler in England.

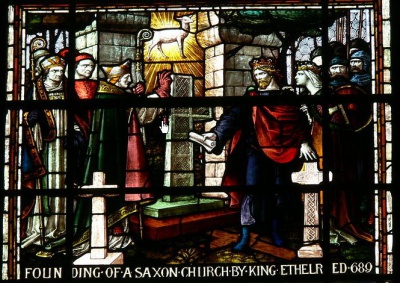

Chester lay outside of the Danelaw but close to its western border. It is unclear to what extent the city was inhabited during parts of this period, although local legend has it seen as a "place of safety" in 783 when Werburgh's relics (died c.699) were supposedly moved there (see below). The foundation legend of St Johns (689) indicates that it was an eccesiastical center prior to this date and there are other tales which may imply some form of continous settlement in post-Roman times, at the date of the Battle of Chester (c616) and in the time of Ecgbert (who occupied it in 828). Plegmund, who was to be come Alfred's archbishop appears to have been associated with the city at some time in the period c875-887. The military importance of Chester was underlined in 893 when it was subjected to a Viking raid. Chester remained important to Alfred's successors. It was refortified after 900 by his daughter Æthelflæd and was the possible site of a significant battle with Vikings in c807. Alfred's son Edward the Elder appears to have had a royal center at Farndon and Chester may have been used as a base by Alfred's grandson Æþelstān prior to the Battle of Brunanburh. Whether Chester was a significant military base after the departure of the Romans and prior to the "Viking Age" is not known.

Hiberno-Norse

The first Viking Age in Ireland began around 795, when Vikings began carrying out hit-and-run raids on Gaelic Irish coastal settlements. Over the following decades the raiding parties became bigger and better organized; inland settlements were targeted as well as coastal ones; and the raiders built naval encampments known as "longphorts" to allow them to remain in Ireland throughout the winter. In the mid 9th century, Viking leader Turgeis or Thorgest founded a stronghold at Dublin, plundered Leinster and Meath, and raided other parts of Ireland. He was killed by the High King, Máel Sechnaill mac Máele Ruanaid, which was followed by several Irish victories against the Vikings and the seizure of Dublin in 849. Shortly after, a new group of Vikings known as the Dubgaill ("dark foreigners") came to Ireland and clashed with the earlier Viking settlers, now called the Finngaill ("fair foreigners"). The wavering fortunes of these three groups and their shifting alliances, together with the shortcomings of contemporary records and the inaccuracy of later accounts, make this period one of the most complicated and least understood in the city's history.

Historical accounts make it clear that when they raided coastal towns from the British Isles to the Iberian Peninsula, the Vikings took thousands of men, women and children captive, and held or sold them as slaves — or "thralls", as they were called in Old Norse. According to one estimate, slaves might have comprised as much as 10 percent of the population of Viking-era Scandinavia. The Annals of Ulster, described a Viking raid near Dublin in A.D. 821, in which "they carried off a great number of women into captivity". Other sources emerged from the Arab world, including the account of the 10th-century geographer Ibn Hawqual, who in A.D. 977 wrote of a Viking slave trade that extended across the Mediterranean from Spain to Egypt.

The Vikings of Dublin engaged in slave-trading as a major local industry. When the Vikings established early Scandinavian Dublin in 841, they began a slave market that would come to sell thralls captured both in Ireland and other countries as distant as Spain, as well as sending Irish slaves as far away as Iceland, where Gaels formed 40% of the founding population, and Anatolia. Mitochondrial DNA mapping of the modern Icelandic population found that up to two-thirds of Iceland’s female founding population had Gaelic origins (either Ireland or Scotland) while only one-third had Nordic roots. In 875, Irish slaves in Iceland launched Europe's largest slave rebellion since the end of the Roman Empire, when Hjörleifr Hróðmarsson's slaves killed him and fled to Vestmannaeyjar. Almost all recorded slave raids in this period took place in Leinster and southeast Ulster; while there was almost certainly similar activity in the south and west, only one raid from the Hebrides on the Aran Islands is recorded. Slavery became more widespread in Ireland throughout the 11th century, as Dublin became the biggest slave market in Western Europe. Its main sources of supply were the Irish hinterland, Wales and Scotland. The Irish slave trade began to decline after William the Conqueror consolidated control of the English and Welsh coasts around 1080, and was dealt a severe blow when the Kingdom of England, one of its biggest markets, banned slavery in its territory in 1102.

The Vikings and Chester

The Vikings would have a very strong influence on the history of Chester for a period of about 200 years from around 873 to 1066. This does not mean that the Vikings arrived suddenly in 873. They were almost certainly present before that year, although they expanded their presence afterwards. The legacy of this influence would be one factor in the establishment of the Norman eardom of Chester and the establishment of a Palatinate whose existence would echo down the centuries. The Timeline for Chester is dominated over this period by events which involve either the Vikings directly, the Viking-originating Normans, or either indirectly.

Their influence even stretches to the Cheshire dialect: the word "rein" as a boundary or ploughland strip occurs only in the dialect of the Wirral and Broxton Hundreds on the western edge of Cheshire. This shows that Viking settlement was more widespread than simply the north-east corner of the Wirral. There is one peculiar piece of evidence for Viking settlement some way south of Chester at Shocklach where there is a church dedicated to St Edith, who was possibly the sister of Æþelstān who gave her (around 926) in marriage to Sihtric Cáech, a hiberno-scandinavian (Viking) King of southern Northumbria and Dublin. Inside the church, tucked away in a corner at the western end near the bell-tower, is a carving on a piece of sandstone about 12 inches square. The parish leaflet states it "seems to show a military figure on horseback", although it has been suggested that it shows "the Flight into Egypt". The citation in the Grade 1 listing identifies it as a "mounted knight" and dates it possibly to the 17th century. The carving is of a man on a horse with, in some interpretations, many legs and therefore actually may be a representation of Odin, the Norse god, and his multi-legged horse, Sleipnir. The Corpus of Anglo-Saxon stone sculpture also suggests that it could be Odin and discusses interpretations, including the fact that the wall in which the stone is set dates from the Norman period (apparently built in around 1150 by Thomas de Shocklach). There is a much damaged stone cross outside of the church and it could be that the stone bearing the carving was taken from that: crosses with a mixture of christian and Viking symbolism are know in other areas where the Vikings settled.

Knutsford is often said to take its name from the Viking Canute (Cnut). Legend has it that in 1016 Canute passed through Knutsford with his army on the march northwards, against the king of Scotland and prince of Cumberland. He is said to have forded the River Lily, or perhaps the Birkin, creating a muddy crossing across the river through the low-lying marsh.

In Chester itself there are some Norse-derived place names, but it is impossible to associate dates with them: several places use the element "Stacks" from "stakkr" - a stack. Flookersbrook is probably from Old Norse "flokari" - one who catches fish. Edgar's Field was at one time "Ketill's Croft" and also in Handbridge is "Grymesdichw Haye" - Grimr's ditch. Handbridge traditionally measured land in Carucates named for the "carruca" heavy plough that began to appear in England in the 9th century, introduced by the Vikings. Elsewhere in Chester land was measured in more standard Anglo-Saxon "hides".

The period of Viking influence on Chester can be split somewhat roughly into several phases:

- Events prior to the arrival of the Great Heathen Army in 865: The Anglo-Saxon kingdoms are largely concerned with wars between each other and with Wales. The Vikings are only an occasional problem.

- Alfreds War with the Danes (865-900): A major invasion followed by settlement resulting in the establishment of the Danelaw.

- The reconquest of the Danelaw (900-954): The descendents of Alfred progressively recapture control of the Danelaw and of Scandinavian York, with some setbacks at times.

- The quiet years of Edgar the Pacific (954-975): A period in which there appear to be comparatively few issues with the Vikings.

- Æþelræd's War with the Vikings (980-1013): Renewed Viking agression following the end of Edgar's peace, possibly triggered by political instability in England.

- Viking Rule (1014-1042): Wholesale "conquest" at the peak of the "Viking Empire".

- Norman Involvement (1043-1066): Restoration of English rule now with the focus shifting to contact with mainland Europe.

- Norman Conquest (1066 and after): The end of Anglo-Saxon England, with considerable involvement of Vikings and Normans.

Many any of these periods end with a sucession "crisis", frequently accompanied with an upsurge in Viking raiding or land-grabbing. This may be due to the Vikings taking advantage of a lack of clear leadership on the part of the English or due to the expiry of treaties with the death of one of the parties.

Events prior to the arrival of the Great Heathen Army in 865:

Mercia reached its peak under Offa (died 29 July 796 AD). Offa's son, Ecgfrith, succeeded him, but reigned for less than five months. Offa had ruthlessly eliminated dynastic rivals leaving only his son. This seems to have backfired, from the dynastic point of view, as no surviving close male relatives of Offa or Ecgfrith are recorded, and Coenwulf, Ecgfrith's successor, was only distantly related to Offa's line. Coenwulf's early reign was marked by a breakdown in Mercian control in southern England. South of the Thames, Britain had been mostly colonised by the Saxons. During Offa's time Mercia mostly dominated the Saxons south of the Thames, but after his death this control rapidly weakened. To the north of Mercia was the border with the kingdom of Northumbria - effectively for much of the time the River Humber. In 789, Annals of Chester (which were wrritten much later) record "Primus Danorum educatus [adventus] in Angliam qui docuerunt Anglos nimis potare" (The first arrival in England of the Danes, who taught the English to drink too much). The Viking raid on Portland in Dorset was the first of its kind recorded in the British Isles, including Ireland. The reeve of Dorchester (a local high-ranking official) went to greet them after they landed, perhaps accustomed to welcoming Scandinavian merchants. He was killed. Viking attacks increased in intensity over the coming decades.

Coenwulf the Mercian died in 821 at Basingwerk near Holywell, Flintshire, probably while making preparations for a campaign against the Welsh that took place under his brother and successor, Ceolwulf, the following year. Coenwulf was the last of a series of Mercian kings, beginning with Penda in the early 7th century, to exercise dominance over most or all of southern England. Ecgbert (Ecgberht) of Wessex ruled from 802-839, and is thought to be descended from the founder of Wessex, Cerdic (514-534), despite being the son of a Kentish noble. He was sent into exile by Offa in 789, and resided at the court of Charlemagne for three years. Ecgbert took back Wessex in 802 when his rival Beorhtric was poisoned by his own wife, Eadburh. In the years after Coenwulf's death, Mercia's position weakened, and the Battle of Ellendun in 825 firmly established Ecgbert of Wessex as the dominant king south of the Humber. He was 55 at the time and would remain ruler of Wessex until the age of 69. Ecgbert is commemorated at Chester Town Hall in one of a series of bas-reliefs showing what are supposed to be key moments in Chester's history.

The fact that Mercia and Wessex could engage in wars with each other as well as expeditions into Wales suggests that they were relatively free of trouble from the Vikings, despite the raid on Portland. There were however some other raids: the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for the year 840 says that Æthelwulf of Wessex (the son of Ecgbert and Alfred's father) was defeated at Carhampton, Somerset, after 35 Viking ships had landed in the area. As regards Chester, nothing is recorded of any trouble with the Vikings. There was certainly intercourse with Ireland, especially that involving the Celtic church and presumably also trade. It is possible that the Mercians were already contemplating trouble in the east and this may have been one reason why Offa built his dyke to formalise and defend his western border, although construction of the dyke is believed to have started just before the first Viking raids.

The there is evidence to suggest that the border between what were later to become North Wales and Cheshire fluctuated considerably over the years. At times the border may have been as far eastward as the Gowy or as far westward as Offa's Dyke, variously placing Chester under Welsh or Mercian control. Chester was a Roman Port and may well have been an important port to the Mercians and part of significant trading links with Ireland. At Meols there is evidence of occupation going back to the neolithic, and there is reason to suppose that trade between Chester and Ireland was established at an early date.

Alfreds War with the Danes (865-900):

Major Danish invasions of England took place in 865. The campaign of invasion and conquest against the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms lasted 14 years and resulted in almost the complete conquest of Britain. Although eventually fought to a stalemate by a resurgent Alfred of Wessex, the Danes were not evicted from all of their conquered teritory and retained considerable land to the east of the country. This has been seen as a pivotal moment in English history and both the historic events and the later views of them are worth some consideration.

The invaders initially landed in East Anglia, where the king (later to become Edmund the Martyr) provided them with horses for their campaign in return for peace. Estimates of the size of the army vary with many clustered around 3000 men. They spent the winter of 865–66 at Thetford, before marching north to capture York in November 866. York had been founded as the Roman legionary fortress of Eboracum and revived as the Anglo-Saxon trading port of Eoforwic - the Danes installed a puppet ruler (Ecgberht I) in Northumbria. During 867, the army marched deep into Mercia and wintered in Nottingham. The Mercians agreed to terms with the Viking army, which moved back to York for the winter of 868–69. In 869, the Great Army returned to East Anglia, conquering it and killing its king Edmund. Edmund later became the he of Bury St Edmund. The army moved to winter quarters in Thetford again. In 871, the Vikings moved on to Wessex, where Æthelred I (brother of Alfred the Great) paid them to leave. The army then marched to London to overwinter in 871-2. The following campaigning season the army first moved to York, where it gathered reinforcements. This force campaigned in northeastern Mercia, after which it spent the winter at Torksey, on the Trent close to the Humber. The following campaigning season it seems to have subdued much of Mercia. Burgred, the king of Mercia, fled overseas and Coelwulf, described in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle as 'a foolish king's thegn' (a puppet) was imposed in his place.

Werburgh (873)

The Vikings were the reason the remains of St Werburgh, and her cult, ended-up in Chester.

The army, led by Halfdan and Guthrum, spent the following winter at Repton on the middle Trent, after which the army seems to have divided. Repton is one of the few places where a Viking winter camp has been excavated. Excavations from 1974 to 1988 found a D-shaped earthwork on a bluff, overlooking an arm of the River Trent, and opened a mound containing a mass grave. The mass grave contained the remains of at least 264 individuals. The bones were disarticulated and mostly jumbled together. Forensic study revealed that the individuals ranged in age from their late teens to about forty, four men to every woman. Five associated pennies fit well with the overwintering date of 873–74. The absence of injury marks suggest that the party had perhaps died from some kind of contagious disease, which raises the possibility that there was a plague raging in the Viking camp.

It was at this time that a much later tradition states that the remains of St Werburgh were relocated to Chester. There are two versions of what followed Werburgh's burial. In the first Werburgh had apparently decided on Hanbury as her final resting place but happened to be at Trentham when she died. The nuns at Trentham refused to give up the body and even instituted security arrangements to prevent its removal. Despite this an expedition from Hanbury succeeded in "miraculously" recovering her remains. According to the second version her brother decided that Werburgh should be moved to the more important site at Hanbury. The shrine of St Werburgh remained at Hanbury until the threat from Danish Viking raids in the late 9th century prompted their relocation to within the walled city of Chester. As recorded in the Annales Cestriensis:

- In the same year, when the Danes made their winter quarters at Repton after the flight of Burgred, king of the Mercians, the men of Hanbury, fearing for themselves, fled to Chester as to a place which was very safe from the butchery of the barbarians, taking with them in a litter the body of S Werburgh, which then for the first time was resolved into dust.

The men of Hanbury may not only have feared the violence of the Vikings at Repton but may also have been concerned about the fact that the Vikings were dropping like flies from what may well have been a plague in their winter quarters.

There are some problems with the traditional Werburgh story. The "Annales Cestriensis" is written in the same hand up to the year 1139 and so was either written at that time or copied from an earlier work which is since lost. Later scribes have added comments in their own hands over periods which far exceed a lifetime. Much of the story of Werburgh comes from "The Holy Lyfe and History of saynt Werburge very frutefull for all Christen people to rede" written by Henry Bradshaw (c.1450-1513). No other chronicles tell the story as recorded in the legend. Some writers have suggested that the "relics" of Werburgh only appeared in Chester at the time that Æthelflæd was promoting her cult. However, that does not realy change the fact that the Vikings were involved at both possible times for her translation. Æthelflæd's promotion of her cult appears to have been part of the establishment of an overall "package" for her newly re-fortified Burh.

Haesten (893)

The Vikings gave rise to the myth that Chester had a castle before the Normans built one.

In 892 (or 893) the Danes again attacked Britain in force. Finding their position in mainland Europe (on the French coast) precarious, this new horde crossed to England in 330 ships in two divisions. They entrenched themselves, the larger body, at Appledore, Kent and the lesser under Hastein, at Milton, also in Kent. The invaders brought their wives and children with them indicating a meaningful attempt at conquest and colonisation. Alfred ("The Great"), in 893 or 894, took up a position from which he could observe both forces. Since the earlier raid Alfred had establish fortified towns under his "burh" system and these provided a much better defence than before. After some confused fighting they made a sudden dash across England and occupied Chester. The following account appears in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle:

- Þa hie on Eastseaxe comon to hiora geweorce. 7 to hiora scipum. þa gegaderade sio laf eft of Eastenglum, 7 of Norðhymbrum micelne here onforan winter 7 befæston hira wif, 7 hira scipu, 7 hira feoh on Eastenglum, 7 foron anstreces dæges 7 nihtes, þæt hie gedydon on anre westre ceastre on Wirhealum, seo is Legaceaster gehaten; Þa ne mehte seo fird hie na hindan offaran, ær hie wæron inne on þæm geweorce; Besæton þeah þæt geweorc utan sume twegen dagas, 7 genamon ceapes eall þæt þær buton wæs, 7 þa men ofslogon þe hie foran forridan mehton butan geweorce, 7 þæt corn eall forbærndon, 7 mid hira horsum fretton on ælcre efenehðe. 7 þæt wæs ymb twelf monað þæs þe hie ær hider ofer sæ comon. (As soon as they came into Essex to their fortress, and to their ships, then gathered the remnant again in East-Anglia and from the Northumbrians a great force before winter, and having committed their wives and their ships and their booty to the East-Angles, they marched on the stretch by day and night, till they arrived at a western city in Wirral that is called Chester. There the army could not overtake them ere they arrived within the ramparts: they besieged the ramparts though, without, some two days, took all the cattle that was thereabout, slew the men whom they could overtake outside the ramparts, and all the corn they either burned or consumed with their horses every evening. That was about a twelvemonth since they first came hither over sea.)

The Chronicle of John Brompton, seems to be the first work to mistakenly have Chester Castle in existence prior to the Norman Earls of Chester. This error was copied by many later authors. The Victorian work "Picturesque England", following Brompton, describes the fortifications at Chester of Alfred's time of being a round sandstone castle:

- The Danes, the following and more terrible invaders, who had been allowed by Alfred the Great to settle in Northumberland, next assailed Chester, and seized the fortress, which was circular and of red stone...

In fact the Danes who attacked Chester were not from Northumberland but encamped in the south. The Danes in Northumbria had not been allowed to setttle there by Alfred, but had conquered it. The obvious puzzle here is why the Danes should suddenly rush across the country from Shoeburyness on the Thames estuary in Essex to Chester. The Danes were coastal raiders who usually targeted a rich source of portable loot - the Danes from Northumberland were busy attacking Exeter (Roman Isca) which Alfred had fortified as a "burh" and north Devon. Alfred had driven the Danes out of Exeter in 877 after they had occupied it for a year. There is a further discussion of what the Vikings might have been trying to achieve on the page relating to the Amphitheatre.

The Viking force which attacked Chester was commanded by "Hastein" a notable Viking chieftain of the late 9th century who made several raiding voyages. During 859–862, Hastein jointly led an expedition with Björn Ironside. A fleet of 62 ships sailed from the Loire to raid countries in the Mediterranean. Eventually he decided to sack Rome, but mistakenly attacked the city of Luna (modern Luni). He tricked his way in by pretending to be a dying Christian convert. Hastein then leapt from his coffin and decapitated a priest before joining his men. According to the traditional version upon finding that the city he had sacked was in fact Luna and not Rome, Hastein was so embarrassed that he massacred everyone there.

Settled back in Brittany, Hastein allied himself with Salomon, King of Brittany against the Franks in 866, and as part of a Viking-Breton army he killed Robert the Strong at the Battle of Brissarthe near Châteauneuf-sur-Sarthe. In 867 he went on to ravage Bourges and a year later attacked Orléans. Peace lasted until spring 872 when the Viking fleet sailed up the Maine and occupied Angers, which led to a siege by the Frankish king Charles the Bald and a peace being agreed in October 873. Hastein remained in the Loire country until 882, when he was finally expelled by Charles and then relocated his army north to the Seine. There he stayed until the Franks besieged Paris and his territory in the Picardy was threatened. It was at this point he became one of many experienced Vikings to look to Britain for riches and plunder. Given the time-span involved there may be more than one "Hastein" as he would have been very old during his British campaign. The Norman monk Dudo of Saint-Quentin wrote of Hastein:

- "This was a man accursed: fierce, mightily cruel, and savage, pestilent, hostile, sombre, truculent, given to outrage, pestilent and untrustworthy, fickle and lawless. Death-dealing, uncouth, fertile in ruses, warmonger general, traitor, fomenter of evil, and double-dyeded dissimulator ..." Dudo of St. Quentin's. Gesta Normannorum. Book 1. Chapter 3

It has been suggested that Chester was not a deserted city at the time that the Vikings fled there, and that they did not occupy the city itself but only the ruins of the Amphitheatre, which may or may not have been converted into a fortified dwelling. Whatever interpretation is taken leads to difficulties. On the one hand, Alfred does not engage the Vikings in a pitched battle at Chester but simply kills a few stragglers and burns all available supplies leaving the Vikings to starve after investing them for only a few days. This presents problems as to what any inhabitants of Chester might have been doing at the time and more importantly what they did over the winter, with Vikings camped on their doorstep and all local food apparently destroyed. On the other hand, if Chester was deserted then why is devastation of the Churches etc, including St Johns not recorded? The exact status of Chester at this time is a recognised historic puzzle which might one day be solved by archaeology, but at present leaves a definite gap in the history of the city.

The 1849 translation Roger of Wendover (died 6 May 1236) confuses Chester with Leicester (but refers to it being on the Wirral). Roger of Wendover gives another version of events and states that after the Battle of Buttington (893):

- "Those who escaped the slaughter fled to Leicester, whose English name is Wyrhale, where they found numbers of their countrymen in a certain town, and were admitted by them into their fraternity. On arriving there, the king, not being able to lay siege to the place, burned all the corn and victuals which he found without the town.. ..In the year of our Lord 896, the wicked band of pagans quitted Leicester and made for Northumberland, and there taking ship, they began again to roam the seas."

Note that Roger of Wendover suggests that the Vikings were already occupying Chester, that "the king" laid siege to the city and that the Vikings apparently stayed until 896.

There is a curious Chester legend which attempts to fill the gap having the people of the city under the control of the Vikings and plotting to overthrow them on Shrove Tuesday. The attack on the Vikings was to begin with the murder of the guards which they had posted, but as the conspiritors approached their presence was given away by the crowing of roosters. This was said to be the origin of a Chester entertainment on Shrove Tuesday where a cockerel was tied down by one foot and players could try to knock it down with a stone flung from 22 yards. This was apparently done in Eastgate Street. There was a small fee to take part but if you knocked the cock down it was yours. Exactly the same "sport", with minor variations, was known to have been played in Abingdon and is also mentioned by Samuel Pepys in his diary entry for Tuesday 26 February 1660/61:

- "Back to Mrs. Turner’s, where several friends, all strangers to me but Mr. Armiger, dined. Very merry and the best fritters that ever I eat in my life. After that looked out at window; saw the flinging at cocks."

"Flinging at Cocks" on Shrove Tuesday is of considerable antiquity but was a national sport. One theory as to its origins, given in a letter in the Stamford Mercury of 1768 said that:

- "Gallieide, or cock-throwing, was first introduced by way of contempt to the French, and to exasperate the minds of the people against that nation: but why should the custom be continued when we are no longer at war with them?"

It is shown in the first print of Hogarth’s “Four Stages of Cruelty". In 1660, an official pronouncement by Puritan officials in Bristol to forbid cock throwing and/or thrashing (as well as dog, cat and fox tossing) on Shrove Tuesday resulted in a riot by the apprentices. Special weighted sticks called "coksteles" were generally used. Sir Thomas More referred to his skill in casting a cokstele as a boy. Given that the sport was so widespread the attribution to a failed attempt to rebel against the Vikings is probably a much later myth.

The reconquest of the Danelaw (900-954):

In 902 the Vikings were thrown out of Dublin. As recorded in the Annals of Ulster:

- "The heathens were driven from Ireland, i.e. from the fortress of Áth Cliath, by Mael Finnia son of Flannacán with the men of Brega and by Cerball son of Muiricán, with the Laigin; and they abandoned a good number of their ships, and escaped half dead after they had been wounded and broken."

Many of these Vikings settled elsewhere, including one group which eventually settled in the Wirral. Some historians have suggested that allowing the Vikings to settle in the Wirral was a strange decision. What may be relevant is that Æthelflæd's brother, Edward the Elder had other issues with the Vikings at the time. Becoming king was not straightforward for Edward. A cousin, Æthelwold, disputed the succession and seized the royal estates of Wimborne, symbolically important as the place where his father was buried, and Christchurch, both in Dorset. Edward brought an army to Dorset, but Æthelwold fled to Viking-controlled Northumbria, where he was accepted as king - although it is not clear whether he was accepted as "king of Northumbria" or simply recognised as having a claim to Wessex. No explanation can be offered as to how he came to be on apparently friendly terms with the Northumbrians. In 901 or 902 Æthelwold sailed with a fleet to Essex, where he was also accepted as king (again it is not clear of what). The following year Æthelwold persuaded the East Anglian Danes (Vikings) to attack Edward's territory in Wessex and Mercia.

The Danes had been in East Anglia since the time of the Kingdom of Guthrum, when it was vested to them by Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum after the somewhat inconclusive Battle of Edington (878). Guthrum had returned to East Anglia, and although there are records of Viking raiding parties in the 880s, Guthrum effectively ceased to be a direct threat and ruled for more than ten years as a Christian king for his Saxon vassals and simultaneously as a Norse king for his Viking ones. He had coins minted that bore his baptismal name of Æthelstan. On his death in 890, the Annals of St Neots, a chronicle compiled at Bury St Edmunds in the 12th century, recorded that Guthrum was buried at Hadleigh, Suffolk.

Coins minted during the short period of Æthelwold's "exile" in the north show that Æthelwold had been proclaimed king in Jórvík (Viking ruled York). He may have been seen as a better choice of overall ruler than the somewhat more anti-Viking Edward. In the autumn of 901, Æthelwold sailed with a fleet from his new allies into Essex. By 902 he and the East Anglian Danes were attacking deep into Mercia, one of Edward's most important allies, as far as Cricklade, in Berkshire where "they seiezed all that they could grab". The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (written by Wessex) appears to paint a picture of Æthelwold as a minor inconvenience to Edward, although that would be typical Wessex propaganda. It is possible that Æthelwold actually presented a serious threat backed by a claim to be the rightful king, and he appears to have concentrated on ravaging royal estates belonging to Edward.

Ingimund (902)

The Vikings may have been involved in the establishment of a mint and eventually a silversmithing trade in Chester.

At about the same time that Edward the Elder was involved in the succession dispute the Hiberno-Norse exile Ingimund sought to settle near Chester. Ingimund was a Viking who had been expelled from Ireland and had attempted to settle in north Wales where he came into immediate conflict with the Welsh. According to the Welsh Annals, Ingimund came to Anglesey and held "Maes Osmeliaun", whilst the Welsh vernacular chronicle reports that Ingimund held "Maes Ros Meilon". The site itself appears to have been located on the eastern edge of Anglesey, perhaps near Llanfaes (effectively the later site of Beaumaris) if the aforesaid place names are any clue. Another possibility is that Ingimund was settled near Llanbedrgoch, where evidence of farming, manufacturing, and trading has been excavated at a Viking-age settlement. There is reason to suspect that the Llanbedrgoch site formed an aristocratic power centre, and that it may have originated as an informal Viking trading centre just prior to Ingimund's attempted colonisation. The centre itself could have provided an important staging post between the Welsh and other trading centres in the Irish Sea region. The conflict with the Vikings is well-attested in the Welsh records but Ingimund's subsequent move to the Wirral is only based on fragmentary evidence, in Irish Annals. The Anglo-Sxon Chronicle, as usual, hardly mentions anything that the Mercians did.

There is no reason to suppose that the events on the Wirral and in East Anglia were related, but any arrangements reached with Ingamund could have been affected by the threat from Danes on two fronts, and the close timing of these two events is often overlooked by historians. Possibly this due to disputes about the dates - with sources disagreeing about the year:

- "... & þær wearð Sigulf ealdormon ofslægen, & Sigelm ealdorman, ... & Sigebreht Sigulfes sunu, ..." ASC(A) s.a. 905 (orig. 904);

- "... & þy ilcan gere wæs þ gefeoht æt þam Holme Cantwara & þara Deniscra." ASC(C) s.a. 902 (Mercian Register)];

- Angus argued that the battle was fought between 24 September and 25 December 902, and perhaps on 12 December 902, but the argument is not conclusive [Angus (1938), 204-6];

- a 961 deed of his daughter shows clearly that the Sigehelm who died at the Battle of Holme was the same person as Sigehelm, father of queen Eadgifu [Cart. Sax. 3: 284-7 (#1064-5)]

Ingimund may well have been a member of the wealthy slave-trading rulers of Viking Dublin before his expulsion and could have offered a substantial cash bribe, which would have been of considerable benefit to Æthelflæd. This may even have been a quanity of silver sufficient to kick-start the expansion of a mint in Chester. The mint certainly flourished under Æthelflæd, when it produced coins of distinctive north-western design. The Norse Kingdom of Dublin, the earliest and longest-lasting Norse kingdom in Ireland. Its territory corresponded to most of present-day County Dublin. The Norse referred to the kingdom as Dyflin, which is derived from Irish Dubh Linn 'black pool'. The first reference to the Vikings comes from the Annals of Ulster and the first entry for 841 AD reads: "Pagans still on Lough Neagh". It is from this date onward that historians get references to ship fortresses or longphorts being established in Ireland. It may be safe to assume that the Vikings first over-wintered in 840–841 AD. The actual location of the longphort of Dublin is still a hotly debated issue. In 902 the kingdoms of Brega and Leinster formed an alliance and drove the Vikings from Dublin. The majority of the exiled Dubliners, led by Ímar ua Ímair, retreated to territory in Scotland over which they exerted some control. The expulsion of the Vikings from Dublin in 902 appears to have resulted in Viking immigration in the Wirral and on Anglesey, but also on Mann, and along the coasts of Cumbria and northern Wales. Although this expansion cannot be solely attributed to the refugees from Dublin, it was their expulsion that appears to have precipitated this new wave of Viking colonisation in the Irish Sea region. The Fragmentary Annals of Ireland asserts that some of Ingimundr's forces in England were Irishmen. In fact, there may well be truth behind this claim as the place name Irby, meaning "farm/settlement of the Irish" (Iri býr), is found on the Wirral amid a cluster of other Viking derived place-names.

Edward Attacks (902)

Possibly with his back now secure from the Hiberno-Norse, Edward now retalliated with a raid on East Anglia, forcing the enemy to return home in order to protect their own lands. When Edward withdrew, the men of Kent lingered and met the East Anglian Danes at the Battle of the Holme (13 December 902). The location of the battle is not known with any certainty although many believe that it was fought at Holme (which is derived from the Norse word for "island") in Cambridgeshire, approximately 7 miles (11 km) south of Peterborough.

The Danes were victorious but suffered heavy losses, including the death of Æthelwold. Other casualties associated with the battle included Eohric, the Danish king of East Anglia and the successor to Guthrum, Beorhsige, son of the ætheling Beornoth, and two holds, Ysopa and Oscetel. Clearly Edward's enemies were more than a mere annoyance as they included not only Æthelwold, aguably the rightful king of Wessex (his father had been King of Kent), but also Eohric the ruler of Anglo/Viking East Anglia and the somewhat mysterious Beorhsige. The last was a member of the Mercia "B-dynasty" of whom Burgred had been the last king before being chased out by the Vikings in (874). Beornoth was possibly one of Burgred's sons and so had a claim to the rule of Mercia rather than Æthelflæd and her husband.

As descibed in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Edward was not present at the battle but (as reported possibly with some pro-Wessex bias) had apparently made some attempt to have the army of Kent withdraw:

- "Then when they wanted to go back out from there [Cambridgeshire], he [King Edward] ordered it to be announced to all his army that they should go out together, then the Kentish remained there against his command, and he had sent seven messengers to them. Then they were surrounded there by the raiding army and they fought there. And there they killed ealdorman Sigewulf and ealdorman Sigehelm and Eadwold the king's theign and Abbot Cenwulf and Sigeberrt son of Sigewulf ... and many others."

The others included Sigelelm's son Sigbeorht. 902 was therefore not only a bad year for the ruling class in Kent but also a critical year for Æthelflæd and her brother Edward, and also appears to have been the time when Æthelflæd's husband first became ill. Had events gone otherwise, it could have led to a quite different future for the descendants of Alfred. Edward still had to deal with Æthelwold's army, but without their leaader he was able to pay them off. According to the historian Martin Ryan ("Conquest, Reform and the Making of England" - 2013):

- "What is striking about Æthelwold's "rebellion" is the level and range of support he was able to draw on: he could call on allies from Wessex, Northumbria, East Anglia and, probably, Mercia and Essex. For a time Æthelwold had a claim to be the most powerful ruler in England. Edward's apparent reluctance to engage him in battle may have been well founded."

Kentish losses included Sigehelm, father of Edward the Elder's third wife, Eadgifu of Kent (she married Edward in about 919) although this makes the dates difficult to reconcile as she is generally said to have been born in 903. Eadgifu became the mother of two sons, Edmund I of England, later King Edmund I, and Eadred of England, later King Eadred, and two daughters, Saint Eadburh of Winchester and (possibly) another Eadgifu. She survived Edward (who died at Farndon) by many years, dying in the reign of her grandson Edgar the Pacific, famous for his "boat trip" on the Dee. Edward's second wife had been Ælfflæd - sometimes said to be the daughter of his cousin and Æthelwold's older brother Æthelhelm (who had died in 897).

Vikings in Chester

In the Wirral, the Norse possibly landed somewhere between "Vestri-Kirkubyr" (West Kirby) and "Melr" (Meols). At Meols over 4000 artefacts and nearly 1000 coins and tokens have been recovered from the eroding shore. The finds, mainly made in the 19th century, date from the prehistoric, Roman, medieval and post medieval periods and are an indication that in the past Meols was a major coastal trading site with links to places as far away as mainland Europe and the Mediterranean. The exiles, led by Ingimund, were granted land in Wirral by Æthelflæd and soon established a community with a clearly defined border, its own leader, its own language (Norse), a trading port, and at its centre a place of assembly or government (þing vollr) - the "Thing" at Thingwall. They also brought their religion with them to "Thor's Stone" (Mjollnir) at "Thorsteinn's farmstead", now Thurstaston Hill. It is also possible that the Norwegian "Labskause" may have come to this part of the country at that time and survived as "scouse". See: Hilbre Island for more.

Archaeology also confirms a Hiberno-Norse presence in Chester itself: a brooch with Borre-Jellinge ornament found at Princess Street/Hunter Street is identical with a brooch found in Dublin, and must have derived from the same mould. So trade had been established with Chester but the Vikings cast covetous eyes on the wealth of the city. In 905 (some sources say 912), the Norsemen revolted and attempted to take the city of Chester. The opening of the story involves a certain amount of treachery:

- At first, the Saxon inhabitants of Chester placed a force outside the city gates and then staged a mock retreat. The Norse followed and the gates were closed behind them, trapping them in the city where a great number were slain.

- Following this, the Saxons came to an arrangement with the Irish, who were "no friends of the Saxons but hated the Norsemen more" to meet with the Norse and propose to betray Chester. Unfortunately this was a double-cross and the Norse that came (unarmed) to the meeting were also slain.

Their subsequent Norse attempt at taking the city took on all the elements of a farce:

- The first Norse attack upon the walls was driven off by dropping rocks upon them. The Norse answer to this was to protect their heads with wooden hurdles supported by wooden beams;

- The Saxon answer to the hurdles was to pour boiling beer on the Vikings (which of course ran through the hurdles). The Norse response to this was to cover the hurdles with animal skins;

- Fire would have been the next Saxon weapon, and the Vikings would have countered this by protecting their assault on the wall with soaking-wet sails from their ships;

- Unfortunately for the Vikings the Saxons has a secret weapon - they threw at the Vikings "all the beehives of the town". For the Vikings, trapped inside their heavy, soaking wet, hide and sail-covered siege shelters - now also filled with very agitated bees - that was enough, and the attempt on the city was abandoned.

"Ingamunds saga" (and the "Three Fragments" of the "Annals of Ireland") repeat the story as follows:

- "..But the other forces, the Norsemen, were under hurdles piercing the walls. What the Mercians and the Irish who were among them did was to throw large rocks so that they destroyed the hurdles over them. What they did in the face of this was to place large posts under the hurdles. What the Mercians did was to put all the ale and water of the town in the cauldrons of the town, to boil them and pour them over those who were under the hurdles so that the skins were stripped from them. The answer that the Norsemen gave to this was to spread hides on the hurdles. What the Mercians did was to let loose on the attacking force all the beehives in the town, so that they could not move their legs of hands from the great number of bees stinging them. Afterwards they left the city and abandoned it. It was not long before they returned."

Curiously the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle does not mention this "Battle at Chester" but skips directly to the refortification (see below). The reason for this omission is not known, and there are several possible explanations:

- It never happened: the Irish simply made it up as a folk-tale. One problem with this explanation is that the Irish are otherwise reasonably accurate as regads Æthelflæd;

- The Wessex scribes followed their familiar pattern and neglected to mention any success by the Mercians;

The later fortunes of Ingamund's people is not entirely certain: there was a sizeable Scandinavian "ghetto" in the southern quarter of Chester later on, centred on the church of St Olave’s (the Norwegian king, Olaf Haraldsson, martyred in 1030), and it would appear that many of them settled down in the city as merchants, possibly giving rise to the Gloverstone enclave. While Olaf was only cannonised in 1164, there was already a St Olave's in York by 1955 when Siward, Earl of Northumbria, was buried there. As stated in the Anglo Saxon Chronicle:

- "This year died Earl Siward at York; and his body lies in the minster at Galmanho, which he had himself ordered to be built and consecrated, in the name of God and St. Olave, to the honour of God and to all his saints."

Some may have returned to Dublin - in 917, Sitric Cáech and his kinsman Ragnall ua Ímair sailed separate fleets to Ireland where they won several battles against local kings. Sitric successfully recaptured Dublin and established himself as king. Over time, the settlers in Dublin became increasingly Gaelicized. They began to exhibit a great deal of Gaelic and Norse cultural syncretism, and are often referred to as Norse-Gaels.

When Edward died at Farndon in 924, he controlled all of England south of the Humber and had concluded treaties with his neighbours to the north, including Scotland, Strathclyde and Scandinavian York. The simplest way of explaining what happened next is that Edward's successor Æþelstān broke his father's treaties as soon as the opportunity to do so presented itself.

Refortification (907)

The Vikings are probably the reason why the City Walls were rebuilt.

The Roman city of Chester was refortified around 907 by the Mercians. The event is recorded in the Chronicle (although versions vary) and a cryptic note from 907 that "Chester was restored" suggests more fighting (or rebuilding) in that year:

- A.D. 907. This year died Alfred, who was governor of Bath. The same year was concluded the peace at Hitchingford, as King Edward decreed, both with the Danes of East-Anglia, and those of Northumberland; and Chester was restored.

Raphael Holinshead (writing in the 1570's) also mentions the same, adding that this was when the walls were extended by Æthelflæd - daughter of Alfred and sister to the King: