Grosvenors

The Grosvenors are without doubt an "interesting lot", while there may well be many erudite works on their history, this part of the website focuses on some of the more quirky aspects of their history.

Nothing New

As part of a county palatine under the Earls of Chester, with a parliament of its own until the early 16th century, Chester was not enfranchised (sent no MPs) until an Act of 1543 since when it returned two MPs to Parliament as a parliamentary borough until 1885, when the representation was reduced to one. From 1679 to 1874, with the exceptions of 1681-1689 and 1701-1715, a member of the Grosvenor family was one of the two MP's for Chester. They have been accused of political chicanery and in particular election-rigging, but in Chester (see Charters) this was nothing new.

Chester first sent representatives to Parliament in 1283. However this was a special case related to the trial of Dafydd ap Gruffydd (11 July 1238 – 3 October 1283), which took place in Shrewsbury before a specially convened parliament. On 30 September, Dafydd ap Gruffudd, Prince of Wales, was condemned to death, the first person known to have been tried and executed for what from that time onwards would be described as "high treason" against the King. Edward ensured that Dafydd's death was slow and agonising, and also historic; he became the first prominent person in recorded history to have been hanged, drawn and quartered (preceded by a number of minor knights earlier in the thirteenth century). On 3 October 1283 Dafydd was dragged through the streets of Shrewsbury attached to a horse's tail, then hanged alive, revived, then disembowelled and his entrails burned before him for "his sacrilege in committing his crimes in the week of Christ's passion", and then his body cut into four-quarters "for plotting the king's death". Geoffrey of Shrewsbury was paid 20 shillings for carrying out the gruesome act.

During the reigns of Edward VI (1547-1553) and Mary (1553–1558) only six men filled the 14 seats available. Richard Sneyd and William Gerard were recorders when first elected, the remainder prominent citizens, all (except Thomas Massey) with known interests in trade. Sir Lawrence Smith’s Membership followed an earlier return for the shire and coincided with one of his mayoralties. These MPs were active on the city’s behalf. In the Parliament of 1547 two Acts of local interest were passed, one for the taking of recognizances (2 and 3 Edw. VI, c.31) and the other for removing weirs in the River Dee (3 and 4 Edw. VI, no.26); two further bills failed, but a proviso in favour of Chester was added to the Act for the relief of the poor (5 and 6 Edw. VI, c.2). The number of taverns was limited to four under the Act controlling the sale of wine (7 Edw. VI, c.5). The city also used its Members to transact other business in London, as when towards the end of 1554 the mayor asked Sneyd and Massey to represent to the chancellor the abuses arising from the incorporation of the merchant adventurers there.

Before 1620 voting was restricted to members of the corporation, though the freemen were not excluded either by statute or by the terms of the city’s charter. The city traditionally elected corporation members, one of whom was normally the recorder. In 1604 Recorder Thomas Lawton occupied the senior place and alderman Hugh Glasier the junior. The death of Lawton in 1606 necessitated a by-election, whereupon the new recorder, Thomas Gamull, was elected in his place. However, when Glasier succumbed to the plague during the fourth session of the Parliament he was replaced by Sir John Bingley who, though a native and freeman of Chester, lived in Westminster. He was elected again in 1614, when he was joined by Edward Whitby, appointed recorder after Gamull’s death.

The parliamentary election of 1620 was the borough’s first recorded contest and witnessed the first significant attempt to bring outside influence to bear on its seats. In mid-November Thomas, Viscount Savage, nominated his brother John of Barrow, for the first seat and supported Bingley’s request to be re-elected as the junior Member. The Savages enjoyed a long connection with Chester and their father, Sir John, had served as mayor in 1607-8. However, this nomination was swiftly forgotten, for in December 1620 Prince Charles’s Council intervened. The prince had been created earl of Chester in 1616 and the Council therefore wrote to William Compton, earl of Northampton and lord president of Wales, instructing him to propose Sir Henry Carey, comptroller of the Household, for the first seat (Carey had no connection with Chester). Northampton complied, though he apologized to the corporation that

- "I do well know [this request] to be improper for me to make unto you"

The corporation preferred to uphold its tradition of returning the recorder as the senior Member, however, and drafted a response explaining that Carey, as a non-freeman, was ineligible. Before it was dispatched, recorder Whitby and Sir Randle Mainwaring brought news from London that Carey had found a seat at Hertfordshire. They also carried fresh instructions from the Council to substitute Sir Thomas Edmondes, a privy councillor whose recent attempt to be returned for Middlesex had failed. On 21 Dec. the corporation composed another letter informing Northampton of this turn of events, disingenuously claiming that they would have been willing to accept Carey, though they had "feared much opposition in the commonalty".

The 1620 election was held on Christmas day, after the corporation met to endorse Whitby and Edmondes as its candidates. This "selection" was announced to a large crowd outside the Commonhall. However, Whitby then announced that Edmondes, a non-freeman whose candidacy he had, up to this point, appeared to support, was ineligible. Instead he nominated his ally, alderman John Ratcliffe, of whom the mayor, William Gamul, and many others strongly disapproved. Familial and factional rivalries between Whitby and Gamul dated back to 1617, when the corporation, led by the powerful Gamul family (of Gamul House), had obtained the dismissal of Whitby’s father and brother from the clerkship of the pentice, which they shared. In 1619 there had also been an attempt to oust Whitby himself from the recordership. The corporation’s dislike of Ratcliffe was motivated by religion and snobbery, as they described him as a puritan, a "chief countenancer of factions" and a man whose "only profession is a beerbrewer". Whitby and Ratcliffe achieved a landslide victory at the hustings. Gamul was furious, alleging that Whitby and Ratcliffe had canvassed among the "basest sort", many of the crowd being "labourers, hired workmen and beggars". He sttated that

- "the recorder’s tenants and servants out-swayed our good desires and carried the election for Mr. Recorder and Mr. Ratcliffe to be our burgesses, which we could not withstand by reason of the unappeasable and unruly carriages of this disordered multitude".

A bitter contest ensued prior to the election of MPs on 10 March 1628, with Mainwaring and Smith standing against Whitby and Ratcliffe:

- "[there] was great contention about the burgesses of the Parliament… both parties laboured all the city either freemen or householders to give their voices on one part or other. Yea many were laboured four or five times over. So great was the contention the one seeking to over-sway the other many were threatened unless they gave their voices to Sir Randle [Mainwaring] and Sir Thomas [Smith] they should lose their houses. The two knights wrought so with all the country gentlemen that had tenants in Chester to give them their voices. Within the Common Hall had like to have been a mutiny but with much ado it was appeased and each man gave his voice particularly so that Mr. Recorder [Whitby] had 631 voices, Mr. Ratcliffe 570, Sir Randle and Sir Thomas had other 300 and odd apiece and far short which vexed them so to see the recorder so well-beloved that they would not subscribe to the commission which went to London. The like labouring was never seen for a city more divided in faction was never seen." (Harl. 2125, f. 59v)

In 1628 as in 1620, the election contest raised surprisingly few doubts about Chester’s franchise.

Sources and Links

Early Grosvenors

Collins Peerage of England states:

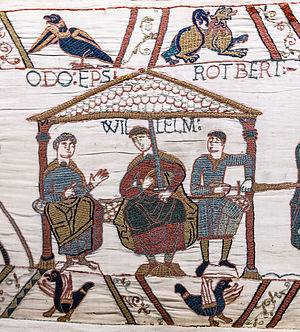

- Among the attendants of the said William, Duke of Normandy, in that victorious expedition into England, were his two uterine brothers, Robert, Earl of Mortaigne in the duchy of Normandy (who afterwards got the earldom of Cornwall), and Odo, Bishop of Bajeux, in the said duchy (created Earl of Kent in 1067) with Hugh Lupus, Count of Avranches, who by his mother was their nephew (of whom mention will be made as Earl of Chester) and Gilbert le Grosvenor, nephew to the said Hugh; as is evident from a record, preserved in the Tower of London, concerning a famous plea (which shall in its proper place be taken due notice of), in a court of chivalry, with relation to a Coat of Arms claimed by Sir Richard le Scrope (who had been Lord High Chancellor of England in 1382) and Sir Robert le Grosvenor

The claim to a family link to the Original Hugh Lupus (Hugh of Avranches) has been the subject of much debate. There are several problems with the claim, not least of which being that given the young age of the original Hugh Lupus at the time of the Norman Conquest nephew "Gilbert" (who seems to be mentioned nowhere else) would have had to be remarkably young at the time of the invasion and it is surprising that this is not recorded. The name "Venour" does turn up in the records at Battle Abbey and this has been suggested as a possible indication that "Gilbert (gros) Venour" (Gilbert the fat hunter) might have existed - although it is unlikely he was Hugh's nephew.

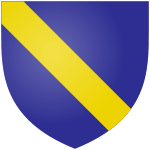

In the heraldic case of Scrope v. Grosvenor (1389), Grosvenor maintained his ancestor, Gilbert, had come to England with William the Conqueror. The case was brought before a military court and presided over by the constable of England - and the first sitting of the Court of Chivalry in the which decided the Scrope/Grosvenor Armorial Bearings was held at St Johns Church, Chester. Curiously, this was not in fact the first time that there had been an argument over this coat of arms. During the reign of Edward III William Carminow, Sheriff of Cornwall had brought a case against Scrope and claimed that his ancestors had been awarded the arms by King Arthur! The records are unclear about the court's ruling. Scrope continued to use the coat of arms in question, and all available versions of Carminow's arms from the time appear to include one additional element, a red label.

In the later Scrope case several hundred witnesses were heard and these included John of Gaunt, King of Castile and Duke of Lancaster, Geoffrey Chaucer and a then largely unknown Welshman called Owain Glyndŵr. The witnesses for Grosvenor stated that:

- ..it was generally reputed in the counties bordering on North Wales that his ancestors had borne the arms azure a bend or from the time of Sir Gilbert de Grosvenor a follower of Hugh Lupus Earl of Chester who was nephew to the Conqueror and that the said arms were to be seen in windows and on tombstones in several churches of Cheshire

The Abbot of the Cistercian Abbey Vale Royal spoke still more positively to the pedigree and arms of Grosvenor saying expressly:

- ..that he has it from chronicles and ancient writings in his monastery that Sir Robert Grosvenor descended in direct line from Gilbert le Grosvenor who in the train of his uncle Hugh Lupus came over with the Conqueror armed in the said arms which he used to the time of his death

John of Gaunt (while at the house of the Friars Carmelites at Plymouth) deposed as follows on June 16th, 1386, and referred to the earlier case:

- We say and testify that at the last expedition in France of our most dread lord and father, on whom God have mercy, a controversy arose concerning the said arms between Sir Richard le Scrope aforesaid and one called Carminow of Cornwall, which Carminow challenged these arms of the said Sir Richard, the which dispute was referred to six knights, now as I think dead, who upon true evidence found the said Carminow to be descended from lineage armed Azure a bend Or, since the time of King Arthur; and they found that the said Sir Richard was descended of a right line of ancestry armed with the same Azure a bend Or, since the time of King William the Conqueror, and so it was adjudged that both might bear the arms entire.

In 1389 the case was finally decided in Scrope’s favor - but Grosvenor was allowed to continue bearing the arms within a silver border. Neither party was happy with the decision, and in 1390 Richard II decided these shields were too similar for unrelated families in the same country to bear. Grosvenor switched to the blue shield with the golden sheaf of corn. The sheaf of corn is interesting, because it first appears in English heraldry on the arms of Hugh de Kevelioc a later Earl of Chester who was infamous for revolting against the king, and the same "garb" was also used by his son Ranulf de Blondeville (a rather more noble knight). There is a very poor representation of the original earl Hugh of Avranches arms in Ormerod's history, and it is possible that this was mistaken for a sheaf of corn (when actually it is a wolf's head). As for Scrope, some websites claim that he was beheaded for his support of Richard II, but that is a confusion between the litigant Richard Scrope (c. 1327 – 30 May 1403), 1st Baron Scrope of Bolton who died on his country estate and Richard le Scrope (c. 1350 – 8 June 1405) an English cleric who served as Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield and Archbishop of York and was executed in 1405 for his participation in the Northern Rising against King Henry IV. However William Scrope, 1st Earl of Wiltshire was executed without trial when Bristol Castle surrendered to Henry's forces on 28 July 1399.

There is another interesting connection between the Grosvenors and the Earls of Chester. The Forests of Mara and Mondrem together formed one of the three hunting forests of the Earls of Chester, the others being the Forests of Macclesfield and Wirral. It was created by Hugh of Avranches, a keen huntsman, soon after he became Earl of Chester, although the area might have been an Anglo-Saxon hunting forest before the Norman Conquest. "Forest", in this context, means an area outside the common law and subject to forest law; it does not imply that the area was entirely wooded, and the land remained largely in private ownership. Hugh de Kevelioc is said to have granted his manor of Budworth together with a half share interest in the forestership of Mara (which included Delamere Forest) to Robert Grosvenor at some time in the 1150s. The bounds of Grosvenor's bailiwick were described in 1361 as being:

- 'from Stanford Bridge along the King's highway as far as Northwich, thence following the bounds of the forest as far as the Darley Brook, and thence following the Darley Brook as far as the bounds of Rushton, and then following the bounds of Rushton and Olton as far as Yemelegh Mill and from the mill following the bounds between Eaton and Alpraham as far as the town of Tarporley and then following the bounds of the said forest as far as Stanford Bridge'.

Being born in 1147, Hugh de Kevelioc would have been a minor at the time and one wonders just how real the grant of the forestership was!

A Richard Grosvenor is said to have accompanied Richard I during the Crusades.

Around 1443 a Raufe Grosvenor is said to have married a Joan of Eton, which later became Eaton, the family home of the Grosvenors.

The Grosvenor MPs for Chester

| Election Year | First member | Second member |

|---|---|---|

| 1660 | John Ratcliffe | William Ince |

| 1661 | John Ratcliffe | Thomas Smith |

| 1673 | Robert Werden | Thomas Smith |

| 1675 | Robert Werden | William Williams |

| 1679 | Thomas Grosvenor (3bt) | William Williams |

| 1681 | Roger Whitley | William Williams |

| 1685 | Thomas Grosvenor (3bt) | Robert Werden |

| 1689 | Roger Whitley | George Mainwaring |

| 1690 | Thomas Grosvenor (3bt) | Richard Levinge |

| 1695 | Thomas Grosvenor (3bt) | Roger Whitley |

| Jan 1698 | Thomas Grosvenor (3bt) | Thomas Cowper |

| Jun 1698 | Thomas Grosvenor (3bt) | Peter Shakerley |

| 1701 | Henry Bunbury | Peter Shakerley |

| 1715 | Henry Bunbury | Richard Grosvenor (4bt) |

| 1727 | Thomas Grosvenor (5bt) | Richard Grosvenor (4bt) |

| Jan 1733 | Thomas Grosvenor (5bt) | Robert Grosvenor (6bt) |

| Mar 1733 | Charles Bunbury | Robert Grosvenor (6bt) |

| 1742 | Philip Henry Warburton | Robert Grosvenor (6bt) |

| 1754 | Richard Grosvenor (1Earl) | Robert Grosvenor (6bt) |

| 1755 | Richard Grosvenor (1Earl) | Thomas Grosvenor (1734-95) |

| 1761 | Richard Wilbraham-Bootle | Thomas Grosvenor (1734-95) |

| 1790 | Thomas Grosvenor (1Mq) | Thomas Grosvenor (1734-95) |

| 1795 | Thomas Grosvenor (1Mq) | Thomas Grosvenor (FM) |

| 1802 | Richard Erle-Drax-Grosvenor | Thomas Grosvenor (FM) |

| 1807 | John Grey Egerton | Thomas Grosvenor (FM) |

| 1818 | Thomas Grosvenor (2Mq) | Thomas Grosvenor (FM) |

| 1826 | Thomas Grosvenor (2Mq) | Robert Grosvenor (Ebury) |

| 1830 | Philip de Malpas Grey Egerton | Robert Grosvenor (Ebury) |

| 1831 | Foster Cunliffe-Offley | Robert Grosvenor (Ebury) |

| May 1832 | John Finchett Maddock | Robert Grosvenor (Ebury) |

| Dec 1832 | Sir John Jervis | Robert Grosvenor (Ebury) |

| 1847 | Sir John Jervis | Hugh Grosvenor (1Duke) |

| 1850 | William Owen Stanley | Hugh Grosvenor (1Duke) |

| 1857 | Enoch Gibbon Salisbury | Hugh Grosvenor (1Duke) |

| 1859 | Philip Stapleton Humberston | Hugh Grosvenor (1Duke) |

| 1865 | William Henry Gladstone | Hugh Grosvenor (1Duke) |

| 1868 | Henry Cecil Raikes | Hugh Grosvenor (1Duke) |

| 1869 | Henry Cecil Raikes | Norman Grosvenor |

| 1874 | Henry Cecil Raikes | John George Dodson |

| 1880 | Beilby Lawley | John George Dodson |

Sir Richard Grosvenor, 1st Baronet

Sir Richard Grosvenor, 1st Baronet (9 January 1585 – 14 September 1645) was born at Eaton Hall, Cheshire, the only surviving son of 17 children. At the age of ten Grosvenor joined the household of John Bruen of Stapleford, a "godly Protestant tutor to children of the local upper gentry", who emphasized the link between "magistracy and ministry". At the age of 13 he went to Queen's College, Oxford, matriculated in 1599 and graduated BA on 30 June 1602 (aged 17). His tutor at Oxford was probably the puritan William Hinde. Hinde became perpetual curate of Bunbury, Cheshire in about 1603. He was a leader of the nonconformists in Cheshire, and clashed with Thomas Morton (bishop of Chester) and wrote .‘A faithful Remonstrance: or the Holy Life and Happy Death of John Bruen of Bruen-Stapleford, in the County of Chester, Esq.,’ Hinde died at Bunbury in June 1629, and was buried there.

In 1602 Grosvenor also became High Sheriff of Cheshire. He was knighted by James I in Vale Royal on 24 August 1617. In 1620 he became MP for Cheshire as a "junior knight of the shire". He was created baronet on 23 February 1622. In 1623 he was again High Sheriff of Cheshire and 1n 1625 High Sheriff of Denbighshire. In 1626 he was removed from the bench, probably for having spoken out in Parliament against the king’s "favourite" (i.e. "toy-boy"), George Villiers, the duke of Buckingham, and for having presented the names of Buckingham's clients to the Common’s committee for recusant officeholders. Despite his removal, Grosvenor served as a Forced Loan commissioner in 1626-7, and persuaded many reluctant Cheshire gentry to contribute. Grosvenor was a keen supporter of measures to limit imports of Irish cattle in exchange for English coin. He noted that over 5,000 Irish cattle had passed through Chester in 1620. Irish merchants were, he said, underselling their English counterparts and draining specie from the realm, causing a 20 per cent drop in Cheshire land values.

He was re-elected MP for Cheshire in 1626 and 1628 and sat until 1629 when King Charles decided to rule without parliament until 1640. His brother-in-law, Peter Daniell (of Over Tabley) stood alongside Grosvenor in the county election of 1626, but whereas Grosvenor was unanimously supported for the first place, Daniell was opposed by (Sir) William Brereton (1st bt.) and Peter Minshull. Grosvenor persuaded Brereton and Daniell to draw lots beforehand to see who would go forward to face Minshull. Brereton was thereby eliminated, but at the election, held in the shire hall, the sheriff was unable to determine which man had the greater number of voices and so ordered a poll to be taken outside on Flookersbrook Heath. In the late 1620's Grosvenor stood surety for the debts of brother-in-law, Peter Daniell, but in 1629 Daniell defaulted on his debts, and for almost ten years Grosvenor was "incarcerated" in the Fleet Prison (until Daniell agreed to pay the debts from his son’s marriage settlement). He led a comfortable existence during his confinement, often being permitted to dine in town, and he made at least one visit to Cheshire. For most of 1636-8 he was sent to live in Reading, and was often in the company of leading Berkshire gentlemen.

In May 1640 he arbitrated a dispute over the parliamentary election for Chester (this involved Brereton the grenade-throwing MP again), and in July 1642 he played a leading role in organizing, and probably also drafting, the Cheshire remonstrance, a petition containing over 8000 signatures, which called on the King and Parliament to settle their differences and avoid Civil War. During the Civil War Grosvenor remained neutral. Grosvenor's detailed diaries make it possible to reconstruct his political views in considerable detail. He was a firm believer in the "divine right of kingship" and in patriarchal authority, but at the same time he staunchly defended the liberties of the subject and of parliament's role as "the representative of the people". Above all, he was concerned to root out the "evil of popery" and to overcome the influence of "evil counsellors" close to the King.

Richard was involved in the lead industry in North Wales. In 1589 the Crown granted the mineral rights in the lordships of Coleshill and Rhuddlan (Halkyn Mountain forms part of this) to a William Ratcliffe of London. In 1597, the same William Ratcliffe was granted a lease of a lead smelting mill and a small plot of land called "Y Thole" by Edward Lloyd of Pentrehobin. (Indicating that the industry was already established). These two rights were then sold to Richard Grosvenor in 1601 and thus began the family's connection with lead mining. Around this time they also accumulated the mineral rights in the lordships of Bromfield and Yale in Denbighshire. These acquisitions enabled this family to control a huge swathe of the industry in the Mold area. From the early days of this industry, the mine owners found it necessary to import labour and expertise from more well-established lead-mining areas, mainly from Cornwall and Derbyshire. These workers operated under the laws pertaining to these other districts whereby the miners kept 9/10ths of the ore and giving the owner or lessees the remainder. This was a situation that Sir Richard did not find to his liking and around 1619 he embarked on a course of litigation against the miners who had petitioned that they had been forbidden to work the mines and been forced to sell to the Grosvenors at his price. This case resulted in victory for Sir Richard in the Court of Star Chamber in 1623.

Grosvenor married three times. His first marriage was in 1600 (while still at Oxford) to Lettice Cholmondley, daughter of Sir Hugh Cholmondeley of Cholmondeley, Cheshire. With her he had a son and three daughters. Lettice died in 1612 and two years later he married Elizabeth Wilbraham, of Woodhey, Cheshire. Following her death in 1621 he married Elizabeth Warburton, daughter and sole heiress of Sir Peter Warburton of Grafton, also in Cheshire. In 1624 he commissioned an elaborate funeral monument to himself, his three wives and the other Cheshire families to which he was connected by marriage. His third wife died in 1627. He died at Eaton Hall in 1645 was buried in Eccleston churchand and was succeeded in the baronetcy by his son Sir Richard Grosvenor, 2nd Baronet.

Sir Richard Grosvenor, 2nd Baronet

Sir Richard Grosvenor, 2nd Baronet (c. 1604 – 31 January 1665) was the son of Sir Richard Grosvenor, 1st Baronet and spent his childhood at Eaton Hall, Cheshire. In 1628 he married Sydney Mostyn, thereby also gaining estates in north Wales. Richard was involved in the Civil War on the Royalist side. In 1643 he was High Sheriff of Cheshire and in February of that year outlawed those who supported the Parliamentary cause in the Battle of Edgehill in the previous October. In July 1659 Sir Richard was a supporter of Sir George Booth in the abortive pro-Royalist Cheshire and Lancashire Rising. Sir George Booth surprised and took possession of Chester on the 19th August, and issued a proclamation declaring that "arms had been taken up in vindication of the freedom of Parliament, of the known laws, liberty and property", and then marched towards York. Having been foiled in other parts of the country, General John Lambert's advancing forces defeated Booth's men at the Battle of Winnington Bridge near Northwich. Booth himself escaped disguised as a woman, but was discovered at Newport Pagnell on the 23rd whilst having a shave, and was imprisoned in the Tower of London.

Sir Richard's son and heir, Roger, was killed in a "duel" by his cousin, Hugh Roberts (of Hafod-y-bwch, near Wrexham), dying on 22 August 1661. When Sir Richard died in 1665, he was succeeded by his grandson Sir Thomas Grosvenor, 3rd Baronet, who was aged only eight at the time. The supposed duel was was over a foot-race which had taken place the day before between Laurence a footman of Roger Grosvenor and a footman called Astyn who worked for John Pulford of Wrexham. Roberts was riding on horseback alongside the riders but Astyn had drawn ahead and Roberts horse was raising dust in the face of Grosvenor's man. An argument ensued and Roberts rode between Grosvenor and the footman. Grosvenor struck Roberts with a stick, and then suddenly leapt off his horse and drew his sword. He went up close to Roberts as he sat on his horse, forcing Roberts to dismount from the other side, and go backwards 3 or 4 steps, when he drew his own sword. Grosvenor ‘made a pass upon him’ which Roberts ‘put by’ and they ‘closed’ together. In the brief clash Grosvenor had sustained a mortal wound. Despite the sponaneous nature of the fight the records of both the Grosvenors and Roger’s wife’s family, the Myddletons of Chirk Castle in Denbighshire, reveal a very longstanding belief among his relatives and descendants that Roger Grosvenor did indeed die in a duel: whereas in fact Grosvenor barely gave his opponent time to dismount and draw his sword to defend himself and the "duel" was a rather ugly and not noticeably honourable fight on a public highway.

Number #9 Lower Bridge Street: The Falcon was the home of Sir Richard Grosvenor during the Civil War. The section of the building facing Lower Bridge Street was once a section of Row, which extended further down the Street, but this was enclosed in 1643 following a successful petition to the assembly by Sir Richard Grosvenor. It was the first such enclosure of The Rows. His petition gave the following reason why the row was an annoyance to himself and his neighbours:

- "..by reason of the moistinesse thereof.."

He also argued that his employment with the garrison of Chester:

- "..tyeth him to inhabit in his said house which is far to little to recieve his familie"

Although no further enclosure of the Rows took place for 25 years, Grosvenor's enclosure of the row started a trend which was to transform Lower Bridge Street. In the late 18thC the building ceased to be the town house of the Grosvenor family. It continued to be owned by them, and between 1778 and 1878 it was licensed as The Falcon Inn. By the 1970s the building had become virtually derelict. In 1979 the Falcon Trust was established, and the building was donated to the trust by the Grosvenor Estate. Between 1979 and 1982 the building was restored by Donald Insall Associates.

Sir Thomas Grosvenor, 3rd Baronet

Sir Thomas Grosvenor, 3rd Baronet (20 November 1655 – 2 July 1700) was the first member of the family to build a substantial house on the present site of Eaton Hall in Cheshire. In 1677 Grosvenor married; he was aged 21 and his wife Mary Davies was 12, he was granted the freedom of Chester and later the same year he became an alderman. The marriage portion which the guardians of the twelve-year-old Mary Davies were able to offer the young Cheshire baronet consisted of some five hundred acres of land, mostly meadow and pasture, a short distance from the western fringes of built-up London. Not all of this was to be available in immediate possession and the income from the land was at that time relatively small, but its potential for future wealth was realized even then. A part approximately one hundred acres in extent and sometimes called in early deeds The Hundred Acres, lay south of Oxford Street and east of Park Lane. With only minor exceptions this part of Mary Davies's heritage has remained virtually intact and formed the lucrative Grosvenor estate in Mayfair.

Before the Grosvenors returned to political life in Chester, the system had become even more corrupt. The by-election on MP Ratcliffe’s death in 1673 (he was the son of the previous John Ratcliffe) produced the heaviest casualties recorded in any constituency in the period. Three candidates entered the field; Williams (the Recorder), the son of a royalist clergyman, Werden, another old Cavalier (see: Bath Street), and James Bradshaw, whose father had represented the city in the second Protectorate Parliament. Werden, the son of a Chester attorney, obtained a letter of support from his master, the Duke of York, while Lord Chancellor Shaftesbury unsuccessfully urged Williams to desist. As a government correspondent wrote:

- "We are like to have a great bustle about it. I look on this city to be two-thirds of the royal party and one-third fanatics. The colonel and the recorder divide our party and the other has the fanatics. I wish our dividing does not make way for him. Our hopes were the recorder might have been taken off by means of the lord chancellor, and then Colonel Werden would, without dispute, have carried it, but the recorder will not be persuaded to desist; he is a Welshman."

Bradshaw stood down but it became clear that a poll would still be necessary, the election was adjourned from the Commonhall to the Roodee, then a field (probably to avoid damage to the Commonhall).

- "The recorder immediately after the adjournment threw off his gown, leaped on men’s shoulders, and commanded his party to carry him to the field, doing this without commanding the multitude to avoid the hall, which is usual on such occasions, which caused such a crowd that nine men were smothered going down the stairs, and many others crushed, some of whom are since dead."

In a further report the MP Joseph Williamson was told that:

- "..the recorder is an obstinate competitor. By his policy he withdrew the under-sheriff from the court, so that the return of the writ is only by the King’s sheriff. The mayor was a great stickler for the recorder, and made many freemen to vote for him after the writ was opened and the election going on, near thirty as I am informed. Now the recorder, having seventeen more freemen’s votes than the sheriff, makes him bustle and make the under-sheriff certify for him. But if the freemen the mayor made during the election were withdrawn, as they ought to be, the colonel would have [the] major votes of freemen. But it has always been practicable here for all inhabitants that pay duties to King and Church to vote."

Thomas Grosvenor was now beginning to become very wealthy and built the first substantial house at Eaton Hall. He commissioned the architect William Samwell to design the house. Building started in 1675 with much of the stone used brought from the ruined Holt Castle further up the River Dee. By 1683 the cost of building the house had risen to over £1,000 (£140,000 in 2015). When Sir Thomas Grosvenor first began to cherish parliamentary ambitions in 1675, his first attempt to qualify himself by obtaining the freedom was rebuffed by a majority in the corporation; but his request was granted two years later. In 1679 Thomas Grosvenor was returned as a MP (Tory) for Chester in the "Habeas Corpus Parliament". In all he was to serve in six parliaments (1679-81, 1685-89, and 1690-1701) dying in office.

At the time there was great political polarization between the Torys and the Whigs. The Whigs' origin lay in constitutional monarchism and opposition to absolute monarchy. The Whigs played a central role in the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and were the standing enemies of the Stuart kings and pretenders, who were Roman Catholic. The first Tories emerged in 1678, when they opposed the Whig-supported Exclusion Bill which set out to disinherit the heir presumptive James, Duke of York, who eventually became James II.

In 1682 the visit to Chester of James Scott, the Duke of Monmouth in September was accompanied by searches for arms, surveillance of those deemed disaffected, a few arrests, and frequent reports to London. Local antagonisms were intensified by the visit (planned by Mayor George Mainwaring, Colonel Roger Whitley, and other leading Whigs). Bonfires were lit, Monmouth was greeted rapturously and riotously by the populace, the mob shouted "Let Monmouth reign, let Monmouth reign" and he acted as godfather at the christening of the mayor's daughter.

In September 1684 Grosvenor was foreman of the Cheshire grand jury which presented the Earl of Macclesfield and several other Whigs as dangerous to the King and kingdom because of their association with Monmouth and their alleged complicity in the Rye House Plot, and recommended that they be bound over to keep the peace. Macclesfield replied with an action of scandalum magnatum in the court of the Exchequer against Grosvenor and several other jurymen, but all were acquitted, the judge declaring that ‘no action lies against an officer doing his duty’. Grosvenor was instrumental in procuring the surrender of Chester’s charter and was named mayor in the new charter of November 1683, which he carried down to the city. He was returned to James II’s Parliament without a contest.

On King Charles II's death in February 1685 Monmouth led the Monmouth Rebellion, landing with three ships at Lyme Regis in Dorset in early June 1685 in an attempt to take the throne from his uncle James II. Thomas Grosvenor (by then Mayor of Chester) raised a troop of horses to support James II agianst the rebellion. On 6 July 1685 at the Battle of Sedgemoor, one of the last full-scale pitched battles on English soil, Monmouth's untrained and ill-equipped force of 4000 could not compete with the 3000 regular army they faced, and was defeated by being outflanked. Monmouth himself was captured and arrested at Ringwood in Hampshire. Parliament passed an Act of Attainder, 1 Ja. II c. 2.and Monmouth was executed by Jack Ketch on 15 July 1685, on Tower Hill. It took multiple blows of the axe to sever his head (anywhere between five and eight). The execution was depicted as a playing card showing the "seven of swords" - the traditional meaning of the card is:

- "Hasty decision, greed and/or thoughtless behavior, the individual acts in an impulsive fashion. It represents secret plans or plots, hidden dishonor, frustration and the possibility of failure."

"Hanging Judge Jeffreys" presided over the "Bloody Assizes" at which harsh sentences were handed out to the Duke of Monmouth's unsuccessful followers - about 1300 being found guilty and either transported or hanged. In 1680 Jeffrey's became Justice of Chester. James II was overthrown by a mostly bloodless coup d'état in the "Glorious Revolution" of 1688.

In August 1688 the government of James II removed the entire Tory Assembly and obliged the city to petition for a new charter, which named the corporation and principal officers, reserved the Crown's right to dismiss individuals, dispensed all members from the prescribed oaths, and restricted the parliamentary franchise to the corporation. Tories Grosvenor and William Stanley, earl of Derby, were among those displaced. Of the 24 aldermen named in addition to the mayor and recorder only 11 had already served as aldermen and four as sheriffs. The attempt to conciliate Whigs and nonconformist protestants was fruitless: the nominated corporation apparently never met

In October 1688 the charters of 1683 and 1688 were annulled by a paniced James II and the city resumed its earlier privileges. Members removed in the purge of 1683 and restored in 1688 included Whigs Mainwaring, Roger Whitley, and Peter Edwards. 1688 brought the "Glorious Revolution" when William of Orange, landed (5th November 1688) an invasion army from the Netherlands. Chester was the scene of the only spontaneous resistance to the Revolution. On the news of the landing of William of Orange, the Roman Catholic Lord Molyneux with two Irish regiments seized Chester Castle, but on 18 December 1688 the Earl of Derby entered the city, which had declared for the Prince, and Molyneux’s forces were disarmed and disbanded.

Grosvenor served as sheriff of Cheshire in 1688–89. In 1689 there was a sharp contest for the city's seats in the Convention: Roger Whitley and fellow Whig alderman George Mainwaring were opposed unsuccessfully by Thomas Grosvenor and Richard Levinge, the former recorder. On 2 Sept. Charles Trelawny MP reported that ‘the frequent and great meetings of Roman Catholics every week at Sir Thomas Grosvenor’s have occasioned his neighbours to complain of him’. One of those visiting Dame Mary was William Massey of Puddington, the same William Massey whose tutor had been John Plessington, executed at Boughton during the "Papist Plot" scare. Grosvenor remained an Anglican but his wife became more deeply involved with Catholicism and began to show signs of mental instability.

1690 saw new elections. The Grosvenor party's prospects of success had been strengthened by a combination of the election of eight of their allies to the assembly in 1689 and the support of the lord lieutenant Lord Cholmondeley, so that on 17 Feb. Whitley’s and Mainwaring’s supporters attempted to hold the election before Grosvenor and Levinge had been able to organize their interest. This effort proved unsuccessful and a bitter campaign ensued, allegations being made that while canvassing Grosvenor had spoken against the new monarchs. Much to the disgust of Whitley, Mainwaring and their interest, agents for the Tory candidates, including the recently removed governor of Chester, Peter Shakerley, began enrolling large numbers of freemen, their entry fees allegedly being paid by Grosvenor, so that over 120 freemen were created in late February and early March. Polling began on 17 Mar. and was soon beset by complaints from Whitley and Mainwaring against taking the votes of the recently created freemen, and by disputes between the borough’s two sheriffs, acting as returning officers. The complaints of the Whitley and Mainwaring interest reached a crescendo when the senior sheriff closed the poll, as the Whig candidates claimed they had ‘several in the crowd that called out to be polled’. When the court of election reassembled the following day requests for the poll to be re-opened were rejected, and both pairs of candidates were declared elected by separate sheriffs. Grosvenor and Levinge, who had led the poll at the end of the 17th, were returned despite the handicap of his wife’s religion.

Grosvenor was involved peripherally in London's first stock market boom. In 1687 there were fewer than fifteen English joint-stock companies. The shares of those companies were held in relatively few hands and were traded infrequently. Yet, by 1691 London’s stock market was booming. One company concerned was "Estcourt’s Lead Mine". The mine was owned by Sir Thomas Grosvenor who, disappointed by the local miners’ inability to exploit it, granted the mining rights to his ‘cousin and friend’ Phineas Bowles, a prominent London broker and stock-jobber, and John Blunt. Bowles, Blunt and Sir Thomas Estcourt, apparently without Grosvenor’s knowledge, turned the project into a joint-stock company nominally headed by John Lethieullier. An unexplained rise in stock price from around £10 to over £100 in late 1693 and early 1694 (by mid-1694 shares were being quoted at £150) apparently confirms that the company was used for speculative purposes. In brief, options were taken to buy the £10 shares back at £20 after a few years - even if they were worth less. The share price in "Estcourt’s Lead Mine" was then manipulated by brokers to push it up, when the options were called upon and the now expensive shares obtained at a cheap price - these were quickly sold to "greater fools" before the bubble burst. Interestingly this was before the South Sea Bubble (1711–1720) and although there had been earlier asset bubbles such as the Dutch "Tulip Mania" (1634-1637 - known in Dutch as "tulpenmanie") it may have been the first actual share bubble and an early example of sophisticated market manipulation.

Two sons, Thomas and Roger, died young. His other three sons all succeeded to the baronetcy, Richard became the 4th Baronet, Thomas the 5th, and Robert the 6th.

Thomas Grosvenor died in 1700, but the story of his wife has a peculiar sequel. Within two months of her husbands funeral Mary Grosvenor decided that she would travel to Rome with her costant companion a father Fenwick. She first travelled to Paris, went on to Rome and then returned to Paris in June 1701. In Paris she was taken ill and was treated with emetics, opium and bleeding. Then, suddenly, the brother of her companion priest, Edward Fenwick announced that he and Dame Mary had been married by Father Fenwick. Mary denied that she had married Fenwick and he sued for "breach of promise". Four years of legal disputes ensued until the supposed marriage was annulled by the Court of Delegates in 1705 (it was almost certainly bogus). In the same year a commission of lunacy was appointed to enquire into her mental state. She was adjudged insane and committed to the care of Francis Cholmondeley of Vale Royal in Cheshire, who had been appointed one of the guardians of her children by Sir Thomas Grosvenor's will. Dame Mary lived on without regaining her faculties until her death in 1730.

Sources and Links

- History of Parliament Online;

- "INHERITANCE": The Lost History of Mary Davies: A Story of Property, Marriage and Madness;

Richard Grosvenor 4th Baronet

Richard Grosvenor 4th Baronet (1689 – July 1732) was the eldest surviving son of Sir Thomas Grosvenor. At the time of his father's death (1700) he was being educated at Eton, and was under the guardianship of Sir Richard Myddelton and Thomas and Francis Cholmondeley. After leaving Eton, he went on the Grand Tour, visiting Switzerland, Bavaria, Italy and the Netherlands. In 1707 he returned to Eaton Hall, Cheshire, and in 1708 married Jane Wyndham of Orchard Wyndham, Somerset. The couple had one daughter, Catherine, who died in 1718. During the following year, Jane Grosvenor died and Grosvenor married Diana Warburton of Arley. They had no children.

The 1710 Chester election was complicated by the suggestion that Richard Grosvenor would attempt to revive his family interest in the borough, but it appears that he was persuaded to desist and Bunbury and Shakerley were returned unopposed, as they had been in the three previous elections. The by-election caused by Bunbury’s appointment as an Irish revenue commissioner in 1711 was also unanimous and, following opposition at Westminster to Shakerley’s proposal that he stand aside in favour of Roger Comberbach, Bunbury and Shakerley were both returned unopposed in 1713. The unchallenged return of Bunbury and Shakerley was not disturbed until 1715, when Grosvenor pressed his claims to a seat at Chester, causing a vigorous contest between the three Tories.

The Whigs took full control of the government in 1715 and remained totally dominant until King George III, coming to the throne in 1760, allowed Tories back in. The "Whig Supremacy" (1715–1760) was enabled by the Hanoverian succession of George I in 1714 and the failed Jacobite rising of 1715 by Tory rebels. The Whigs thoroughly purged the Tories from all major positions in government, the army, the Church of England, the legal profession and local offices. The Party's hold on power was so strong and durable, historians call the period from roughly 1714 to 1783 the age of the "Whig Oligarchy".

In 1715 Grosvenor was returned as MP for Chester and in the same year he was elected as mayor of the city. The Grosvenor interest, having reasserted itself, held at least one of the Chester seats continuously until 1874. Around this time he was suspected of being a Jacobite supporter, although in 1727 he participated (as "Grand Cup Bearer") in the coronation of George II. In that year, Grosvenor and his brother Thomas, won both MP seats for Chester. His mother, Mary, had inherited the manor of Ebury, 500 acres of land north of the Thames to the west of the City of London, which remained largely untouched by the Grosvenors until the 1720s, when they developed the northern part (Mayfair) around Grosvenor Square. Richard died in July 1732.

Sir Thomas Grosvenor, 5th Baronet

Sir Thomas Grosvenor, 5th Baronet (1693 – February 1733) was the second surviving son of Sir Thomas Grosvenor, 3rd Baronet. In 1727 Grosvenor and his older brother Richard won both MP seats for Chester (Thomas was re-elected in 1733). Thomas Grosvenor succeeded to the baronetcy when Richard died in July 1732. However by that time he was already unwell and, having been advised to travel to Italy, he died in Naples in the February of the following year.

Sir Robert Grosvenor, 6th Baronet

Sir Robert Grosvenor, 6th Baronet (7 May 1695 – 1 August 1755) was the youngest surviving son of Sir Thomas Grosvenor, 3rd Baronet. In 1730 he married Jane Warre of Swell Court and Shepton Beauchamp, Somerset. They had two sons (Richard, later Earl Grosvenor, and Thomas) and four daughters. Initially they lived in Somerset, but when Grosvenor succeeded to the baronetcy, they moved to Eaton Hall. Sir Robert became the MP for Chester in January 1733. When he died in 1755 (still MP) he was succeeded by his elder son, Richard. His second son, Thomas (1734–1795), was MP for Chester from 1755 until his death in 1795.

Thomas Grosvenor

The second son of Sir Robert (1695-1755), Thomas (1734–1795), was MP for Chester from 1755 until his death in 1795. The Tory party ceased to exist as an organised political entity in the early 1760s. Grosvenor married Deborah Skynner, in 1758. Their second son Richard Erle-Drax-Grosvenor was MP for Chester while their third son Thomas Grosvenor was a distinguished military commander. He played a prominent part as the leader of the St. Alban’s Tavern group’s attempt to promote a union of parties in 1784. The group were largely composed of 'independent country gentlemen' who held themselves free from party allegiance. On 2nd February 1784 he successfully moved a House of Commons motion which called "for a firm, efficient, extended and united Administration" (c.f. "strong and stable government"). Afterwards, ‘tunbellied Tommy Grosvenor’, as one jaundiced observer of that enterprise dubbed him, supported William Pitt, to whom he applied unsuccessfully for a peerage in 1788. His only reported speech after 1790, when he came in again for Chester on the family interest, was against abolition of the slave trade, 18 Apr. 1791:

- "he had twenty reasons for disapproving the idea ... and the first, was that the thing itself was impossible, and therefore he would not give the other nineteen ... He acknowledged that it was not an amiable trade; but neither, said he, is the trade of a butcher very amiable, and yet a mutton chop is, notwithstanding, a very good thing."

Grosvenor died in February 1795, aged 60.

Sources and Links

Richard Grosvenor, 1st Earl Grosvenor

Richard Grosvenor, 1st Earl Grosvenor Bt (18 June 1731 – 5 August 1802), became MP for Chester in 1754 and continued to represent the city until he became Baron Grosvenor in the House of Lords. He was mayor of Chester in 1759. In 1769 he paid for the re-building of the Eastgate. In 1769, Grosvenor extended his estate by the purchase of the village of Belgrave and the manor of Eccleston.

On first becoming an MP, Grosvenor was, like his father, a Tory, but later he came to support the ideas of Whig William Pitt the elder. Richard was first elected MP for Chester in 1754, holding the seat until 1761. In 1758 he declared himself in favour of the Pitt-Newcastle coalition and was created Baron Grosvenor in 1761. However when the Tory Earl of Bute became Prime Minister the following year, Grosvenor changed his allegiance back to the Tories. When Pitt was returned to power in the Chatham Ministry of 1766–68, Grosvenor again returned to support him.

In 1764 Grosvenor married Henrietta Vernon, a "noted beauty" and they subsequently had four sons. They met during a rainstorm and were married within a month. The marriage was not happy, not only was Richard a heavy gambler (up to a quarter of a million in one night), but he was a frequent customer of London brothels.

Henrietta had an affair with Henry, Duke of Cumberland, the younger brother of George III. In 1769, Henry and Henrietta were discovered at a friend's house in Cavendish Square, London, having sex, which led to Grosvenor bringing an action against the Duke for "criminal conversation" (adultery). Lord Grosvenor was awarded damages of £10,000, which together with costs amounted to an award of £13,000. Grosvenor could not sue for divorce under the law at that time because he was also known to be guilty of adultery himself. The couple separated with Henrietta getting an allowance of £1,200 per year. Despite Henrietta have fallen to the charms of the Duke of Cumberland, while her husband was whoring and gambling his way round Lomdon, Henrietta was seen as the villan, and the press followed he around to see what other "scandalous" activity could be reported - the best they managed was that she turned up at the opera with a different man every night.

Lord Grosvenor was infamous for his keeping "low company". He apparently liked getting his women from the filthiest parts of London. Ann Sheldon, his short-term companion, reported the pair of them had contracted lice following one of his amorous exploits. Long after her relationship with Lord Grosvenor was over, Ann Sheldon wrote her memoirs and published them as the "Authentic and Interesting Memoirs of Miss Ann Sheldon: (now Mrs. Archer:) ... Written by Herself". She writes how she brought him poor girls from Westminster Bridge covered in vermin and was astonished at the medley of mistresses that filled his house:

- "the garret was inhabited by pea-pickers - the first floor by a woman of elegance, - the parlour by women servants, - and the kitchen by a negro wench."

She also describes the end of their relationship:

- "Indeed, after this period, I received very few visits from his Lordship - nor did he ever fulfill any of his promises to me. After all the trouble he had given, his memory failed him in the rewards he had declared should follow it; but made good the words of pppor Mr Walsingham, who used to observe that his generosity was by no means brilliant; and Lord Bateman, for once in his life advised me well, in recommending me to have nothing to do with Grosvenor. "Nobody will tempt you, said he, with such fine promises, and no one will be so backward in performing them. He will bid you, continued he, to hire a house, and that it shall be furnished at his expense without delay; but no sooner is the house got, than he will refuse to put a scraper at the door,- give you a rush-bottom chair to sit on,- or even to purchase a penny-worth of sand to strew in your passage."

Grosvenor established horse-breeding studs at Wallasey and at Eaton. His horses won the Derby on three occasions and the Oaks six times. Notable racehorses included: Faith, Ceres, Maid of the Oaks, Pot-8-o and Gimcrack.

During the 1770s he supported Lord North during the American War of Independence. He voted against Fox's India Bill in 1783 and was rewarded by William Pitt the Younger with title of Earl Grosvenor the following year. Grosvenor died at Earls Court in 1802 and was buried in the family vault at St Mary's Church, Eccleston. At the time of his death, his assets amounted to "under £70,000" (£5,450,000 in 2015), but his debts were "over £100,000" (£7,790,000 in 2015).

Field Marshal Thomas Grosvenor

Field Marshal Thomas Grosvenor (30 May 1764 – 20 January 1851) the son of Thomas (1734–1795).

He was commissioned into the 1st Foot Guards on 1 October 1779, and, the following year, was in charge of security at the Bank of England during the Gordon Riots. Promoted to captain on 20 April 1784 and lieutenant-colonel on 25 April 1793, he took part in the Flanders Campaign including the retreat into Germany in Spring 1795. Thomas took part in the Anglo-Russian invasion of Holland in August 1799 and was promoted to brigadier-general while serving under Sir Ralph Abercromby in Holland on 18 November 1800. Promoted to major-general on 29 April 1802, Grosvenor held various brigade commands in Southern England between 1803 and 1805. Grosvenor served as a brigade commander at the Battle of Copenhagen in August 1807 for which he was rewarded with promotion to lieutenant-general on 25 April 1808. In Autumn 1809 he was deployed to Walcheren in the Netherlands where he served as deputy commander of a division led by Sir Eyre Coote during the disastrous Walcheren Campaign which ended in failure when many of the British troops died of "Walcheren Fever", thought to be a combination of malaria and typhus. Over 4,000 British troops died (only 106 in combat) and the rest withdrew on 9 December 1809. Grosvenor was promoted to full general on 12 August 1819.

He was elected MP for Chester in 1795. He opposed a bill against bull-baiting introduced in 1802 - there was an annual Bull Bait at the High Cross in Chester until the practice was outlawed in 1803. Otherwise, he remained a very poor attender who voted infrequently and confined his few remarks to military matters. In January 1810 he spoke in Parliament in support of Henry Herbert's demands for an inquiry into the Walcheren Campaign and the same year was elected mayor of Chester. He kept aloof from the controversies surrounding the duke of Wellington’s visit to Chester in December 1820. Also in 1820, during the Cato Street Conspiracy, and following his pronouncements against the "diabolical" Cato Street conspirators, he had a narrow escape when an angry mob overturned his carriage into the River Dee. The Cato Street conspiritors were less lucky. On 1 May 1820 five were hanged and after the bodies had hung for half an hour, they were lowered one at a time and an unidentified individual in a black mask decapitated them against an angled block with a small knife (an axe made specially was not used}. Each beheading was accompanied by shouts, booing and hissing from the crowd and each head was displayed to the assembled spectators, declaring it to be the head of a traitor, before placing it in the coffin with the remainder of the body. It could have been worse - the original sentence was to be "hanged, drawn and quartered" but this was commuted.

In 1821 he did not vote at all and in October Chester refused to elect him an alderman. He stood down as Member of Parliament for Chester in 1826 to make way for his cousin's son, Robert Grosvenor (1801-1893), and instead became Member of Parliament for Stockbridge.

He had a keen interest in horse racing and his horse, Briseis, won the Epsom Oaks in June 1807.

Sources and Links

Richard Erle-Drax-Grosvenor

Richard Erle-Drax-Grosvenor (5 October 1762 – 8 February 1819) was elected MP for Chester in Decemmber 1802 (succeeding to Robert (1767-1845)), and held the seat until May 6th 1807. Although he was "undoubtedly well disposed" and "expressed the utmost willingness to comply", he and his brother, his colleague at Chester, each wished the other to make the first move, being "fearful of offending Lord Grosvenor", who was "strongly disinclined to Mr Pitt, on account of the Catholic question". After Pitt’s death Lord Grosvenor went over to the Whigs, but Drax Grosvenor did not follow his line. He was a die-hard as regards slavery and opposed the slave trade abolition bill, 23 Feb. 1807.

Previously he had been MP for East Looe (September 1786-Arpil 1788) and Clitheroe (September 1794-1796) leaving the second seat to make way for the son of Assheton Curzon, who had put him up for it. On leaving the Clitheroe seat, he asked Pitt for a peerage, but met with a flat refusal. He returned once again to the House of Commons in 1818 when he was returned for New Romney, a seat he held until his death the following year. Hardly any trace of actual parliamentary activity can be discovered.

Sources and Links

Robert Grosvenor, 1st Marquess of Westminster

Robert Grosvenor, 1st Marquess of Westminster, KG (22 March 1767 – 17 February 1845) was the son of Richard Grosvenor, whom he succeeded in 1802 as 2nd Earl Grosvenor. He was created Marquess of Westminster in 1831. In 1790 he was elected as MP for Chester and held the seat until 1802, when his father died and he became the 2nd Earl Grosvenor. The Chester MP seat was passed to Richard Erle-Drax Grosvenor. Grosvenor was Mayor of Chester in 1807–08, and was responsible for the building of Thomas Harrison's Northgate in the city in 1810.

Robert Grosvenor was initially a Tory, but shifted to the Whigs after William Pitt (the Younger's) death in 1806. A letter of 14 May 1804 "remonstrating against his too liberal grants of the peerage" to lawyers, soldiers and sailors was apparently never forgiven by Pitt, who had his revenge by ignoring Grosvenor’s letters recommending a friend to the vacant deanery of Chester in December 1805. At the time of his move to the Whigs, the story went around that he did so "in consequence of being refused by Mr Pitt the first lordship of the Admiralty" (there is no evidence this was true). His narrow religious views were expressed in his motion of 27 May 1799, seconded by Wilberforce, for a bill to suppress Sunday newspapers, which in his view had become "an additional weapon in the hands of infidelity".

Elections in Chester continued to be riotous affairs. Hemingway, writing in 1826, reported:

- "Of all the places in the kingdom which have heen contested during the late general Election, the city of Chestet has heen distinguished ahove most others for the virulence of party feeling, the acrimony of personal hostility, and the violence of popular outrage."

It is often stated that the first stone of Thomas Harrison's Grosvenor Bridge was put in place by the Marquis of Westminster. This is not entirely accurate as the stone was laid on the 1 October 1827, when Robert was still Earl Grosvenor. Grosvenor died at Eaton Hall on 17 February 1845 and was buried in the family vault at St Mary's Church, Eccleston.

Grosvenor was a major developer of Belgravia in London and a statue there (by Jonathan Wylder, 1998) shows him studying plans of the area, with his foot resting on a milestone inscribed CHESTER | 197 | MILES, a reference to his estate at Eaton Hall in Cheshire. On either side sit two talbots, the supporters from his coat of arms, which is shown on the front of the plinth. On the back of the plinth are bronze reliefs with the 1821 plan of Belgravia iand the 1998 situation. The text panels on the plinth read:

"Under the direction of sir robert grosvenor, thomas gundy, the grosvenor estate surveyor, presented the above layout to the grosvenor board in 1825. from sir robert's vision arose the elegant buildings, grand squares and colourful gardens that are now belgravia. The classical terraces of belgrave square were designed by george basevi, architect to the haldimand syndicate, most of the buildings were erected under the control of the great victorian developer thomas cubitt."

"The grosvenor family came to england with william the conqueror and have held land in cheshire since that time. In the seventeenth century, sir thomas grosvenor, third baronet, married mary davies, a london heiress. her dowry was part of the manor of ebury. the land developed by their successors as mayfair in the eighteenth century, followed by belgravia and pimlico in the nineteenth century"

"In 1979, gerald cavendish grosvenor became the sixth duke of westminster. he commissioned this statue in 1997."

"the hounds on the monument are talbot dogs, introduced to this country by the normans as hunting dogs. now extinct, they were the ancestral stock of the modern bloodhound. talbot dogs were added to the grosvenor coat of arms in the seventeenth century. the gold wheatsheaf, known in heraldry as a 'garb', appeared on the coat of arms for the first time in 1398."

Sources and Links

- History of Parliament Online;

- John Monk on the 1809 elections;

Richard Grosvenor, 2nd Marquess of Westminster

Richard Grosvenor, 2nd Marquess of Westminster KG, PC (27 January 1795 – 31 October 1869), was elected as Whig MP for Chester in 1818 and was later appointed as a Justice of the Peace. In 1830 he was elected MP for Cheshire until the constituency was divided in 1832, and from then until 1834 he represented South Cheshire. Despite criticism of his failure to vote against the repressive measures adopted after the Peterloo massacre, he topped the poll in Chester following the violent contest of 1820.

Reports in September 1825 that he had killed an Irishman in a duel were entirely unfounded.

Belgrave habitually suffered from bouts of earache and temporary deafness, and his absence for this reason from the division on Catholic relief, 6 Mar. 1827, encouraged speculation in the anti-Grosvenor Chester Courant that his indisposition was ‘affected’. This the pro-Grosvenor Chester Chronicle naturally denied.

He was Lord Lieutenant of Cheshire from 1845 to 1867 and Lord Steward of the Household between 1850 and 1852 in the Whig administration headed by Lord John Russell. On 22 March 1850 he was admitted to the Privy Council. He was presented with the Order of the Garter on 6 July 1857. Of his political activity it is said that "he seldom spoke in the House of Lords". Grosvenor continued the family interest in horse racing and, when he was living in the country estate, he spent time hunting and fishing. He gave generously to charity, and built and restored churches. He was an early patron of the Chester architect John Douglas. Lord Westminster died at Fonthill House, Fonthill Gifford in Wiltshire on 31 October 1869 after a short illness and was buried in the family vault in St Mary's Church, Eccleston. His wealth at death is recorded as being under £800,000 (£64,480,000 as of 2015).

Richard was responsible for the donation of the land which became Grosvenor Park. His statue in the park was unveiled on 1st July 1869, but neither the Marquess nor his wife attended. The Marquess was already terminally ill and his wife did not want a public unveiling. There is no record that the Marquis ever actually saw the statue, after unveiling. Grosvenor’s parents had instilled “high moral principles” in their children, and these stayed with Richard throughout his life. He has been described as “of austere character and unswerving devotion to duty as family man, politician and landlord”. His obituary in The Times says “he administered his vast estate with a combination of intelligence and generosity not often witnessed”.

The plinth of the statue is inscribed:

- "Richard: Second Marquess of Westminster: K.G. The Generous Landlord: The Friend of the Distressed: The Helper of all Good Works: The Benefactor to this City: Erected by Tenants Friends and Neighbours; AD 1869".

This is the second inscription: the first was changed because it had "2nd" in figures (now written as ‘second’) and had spawned the joke of "the tuppenny Marquess" (two old pence were written as ‘2d’).

Sources and Links

Robert Grosvenor, 1st Baron Ebury

Robert Grosvenor, 1st Baron Ebury PC (24 April 1801 – 18 November 1893) was the third son of Robert Grosvenor, 1st Marquess of Westminster. He became MP for Chester in 1826 and held the seat until his resignation in 1847.

Grosvenor was born at Millbank House, Westminster, and named after his father, one of the wealthiest noblemen in England. He was educated at Eton and Oxford and embarked on a tour of the continent with his brother Thomas in the summer of 1819, only to return in haste in September for the wedding of their eldest brother Lord Belgrave, Member for Chester. His new sister-in-law thought him "full of entertainment and fun ... a most amiable creature and easy friend". Disappointed in love, he set out for the continent in July 1822 and remained abroad until December 1823. His kinsman General Thomas Grosvenor made way for him at Chester at the general election in June 1826, when he was returned in absentia after a severe contest. On 13 April 1829. he set out on a "fact-finding" tour of the Eastern Mediterranean, where he was privy to the negotiations between the Russians and Turks. After visiting consulates in the Greek Islands, Constantinople, Malta, Tunis and Tripoli, he prolonged his travels by taking a passage to Cadiz, where on 12 June 1830 he wrote informing his mother that he would return forthwith via Barcelona and Paris:

- "I know not what may be my father’s intentions with regard to me at the ensuing elections. You do not ask me to return home, but I think from the tenor of your correspondence that you do not forbid me altogether to do so. You have had no opportunity of writing to me since the king’s health declined so rapidly, and, after due consideration, I do not think I shall be doing my duty towards my father if I do not at least put it in his power to make what use of me he shall think fit, in case of His Majesty’s demise."

Lord Grosvenor put him forward alone for Chester, where he arrived to canvass on 24 July 1830. His "three year sojourn on the continent" was severely criticized, but his return with the Tory Sir Philip Grey Egerton was unopposed. An edition of his travel journal was published afterwards to raise funds for Chester Infirmary. His re-election in 1830 was opposed by the Independent party in Chester, who denounced him "not only as the son of a peer who is a notorious and powerful boroughmonger, but a pensioner upon the public purse, and as a man who has been deficient in the performance of his public duties". He defeated their absent nominee Foster Cunliffe Offley in the ensuing poll. He "inadvertently omitted to take the oaths before taking his seat", and a second by-election was held, 15 Mar. 1831, when his return was not opposed. Chester returned him and the reformer Cunliffe Offley unopposed at the general election of 1831. The same year he was married to Wellington’s niece Charlotte (eldest daughter of Henry Wellesley). Lord Wellesley informed her father, who was then ambassador in Vienna:

- "I think you will be satisfied with the connection. Mr. Grosvenor appears to me to be an excellent man of very good manners and steadiness of conduct. I believe the whole family to be very amiable and worthy".

The duke, who also lent them Stratfield Saye for their honeymoon, gave the bride away. This might seem odd as her father Henry was still alive, but he was possibly serving abroad as Ambassador to Austria. There is also possibly a faint whiff of scandal here, as Charlotte's mother (Charlotte Paget, Marchioness of Anglesey) had "run away" with Henry Paget. Referring to the incident in later years, when Paget, now Lord Uxbridge, was assigned to Wellington as his second-in-command at the Battle of Waterloo, Wellington, who was well-known for his sharp wit, is said to have commented:

- "Lord Uxbridge has the reputation of running away with everybody he can. I’ll take good care he don’t run away with me".

The British Homeopathic Association was founded in 1847 by Robert Grosvenor, Richard Walter Heurtley, John Epps, Marmaduke Blake Sampson and Thomas Uwins.

Grosvenor presented Chester’s civic address to Princess (later Queen) Victoria when she opened the Grosvenor Bridge over the River Dee, 16 Oct. 1832, and she sponsored his daughter Victoria Charlotte at her christening next day. The Grosvenor family's direct influence over the corporation was broken by the Municipal Corporations Act of 1835 and the first council elections at the end of that year.

Sources and Links

Hugh Lupus Grosvenor, 1st Duke of Westminster

Hugh Lupus Grosvenor, 1st Duke of Westminster KG, PC, JP (13 October 1825 – 22 December 1899), was the second and eldest surviving son of Richard Grosvenor, 2nd Marquess of Westminster and Lady Elizabeth Leveson-Gower. He left Oxford in 1847 without taking a degree to become MP for Chester. This seat had been held by his uncle, Robert Grosvenor, who decided to move to one of the two unopposed Middlesex seats. In 1851 he toured India and Ceylon. The following year, on 28 April, he married his first cousin, Lady Constance Sutherland-Leveson-Gower. By 1874 the couple had eleven children, eight of whom survived into adulthood; five sons and three daughters. In 1880 Constance died from Bright's disease. Two years later, in June 1882, Grosvenor married Katherine Caroline, the third daughter of the 2nd Baron Chesham and Henrietta Frances Lascelles, who was then aged 24; she was younger than the duke's eldest son and two of his daughters. They had four children, two sons and two daughters. On the death of his father in 1869, he succeeded as 3rd Marquess of Westminster and entered the House of Lords (his seat as MP for Chester went to his cousin, Norman). His maiden speech in the Commons was made in 1851 in a debate on disorders in Ceylon, shortly following his tour of the country. Otherwise he took little interest in the affairs of the House of Commons until 1866 when he expressed his opposition to Gladstone's Reform Bill. This played a part in Gladstone's resignation, the election of the Conservative Derby government and Disraeli's Second Reform Act. The relationship between Grosvenor and Gladstone later improved and in Gladstone's resignation honours in 1874, Grosvenor was created the 1st Duke of Westminster.

After inheriting the estate, one of his first acts was to commission a statue of his namesake, the Norman Hugh of Avranches, who had been the 1st Earl of Chester, from G. F. Watts, to stand in the forecourt of the hall. Whether there was actually any relationship between the two Hugh's is discussed here. He had Eaton Hall reconstructed at enormous expense.

He was one of the most successful British race horse owners of all time - the character "Colonel Ross" in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's short story Silver Blaze is believed to be based on Hugh Grosvenor. The former Railway Tavern public house in Brook Street, later renamed as the "Ormonde" - now the Ormonde Hotel - is named after one of his favorite racehorses. "Ormonde" (1883–1904) was an English Thoroughbred racehorse, an unbeaten Triple Crown winner, generally considered to be one of the greatest racehorses ever. He also won the Champion Stakes and the Hardwicke Stakes twice. At the time he was often labelled as the 'horse of the century'. Ormonde was trained at Kingsclere by John Porter for the 1st Duke of Westminster. His regular jockeys were Fred Archer (who features on the sign outside the hotel in the correct colours) and Tom Cannon. After retiring from racing he suffered fertility problems, but still sired "Orme", who won the Eclipse Stakes twice.

It has been suggested that "Ormonde's" sire was the model for "Silver Blaze" in the Sherlock Holmes story of the same name, first published 1892. In the same way, "Colonel Ross" in the story is said to be based on one of the Grosvenors - the first Duke of Westminster. Eaton Stud bred many great names in racing notably "Sceptre", "Peregrine", and "Bend Or". The latter being the sire of "Ormonde". In 1880 the Epsom Derby was won by "Bend Or" and "Robert the Devil" was placed a very close second. Fred Archer had ridden to the victory after taking doses of a powerful laxative to get his weight down to 8st 10lb. However a few weeks after the running of the Derby an objection was made by the owners of "Robert the Devil": "on the ground that Bend Or was not the horse he was represented to be, either in the entry or at the time of the race." A groom suggested that "Bend Or" (ridden to a win by Fred Archer) had been replaced by a disguised "Tadcaster" (also from the Eaton Stud). Bearing in mind that the groom, one Richard Arnull, had been fired by Westminster and was working out his notice when he made the allegation, it might have been construed as a mischievous, even malicious, attempt to embarrass his employer. After much publicity (even in the New York Times) the claim was dismissed by the Jockey Club, although the groom maintained that a substitution had occurred for the rest of his life - as did his two sons, who also worked at Eaton. Like "Silver Blaze", "Bend Or" was marked with a distinctive white "blaze" on his face. In the Holmes story the horse is disguised by covering this blaze, and after Holmes solves the mystery wins a race still disguised. Research by Mim Bower of Cambridge University (Institute for Archaeological Research), first published in 2012, compared DNA of "Bend Or" (his skeleton was preserved at the Natural History Museum) to that of "Tadcaster" descendants and other relatives. Both chestnut colts were by the stallion "Doncaster" but "Bend Or" was out of "Rouge Rose" and "Tadcaster" was out of "Clemence". And the DNA results show that the 1880 Derby winner was out of "Clemence" making the winner not ""Bend Or" but "Tadcaster". The two had indeed been switched, either as foals or later - the skeleton known as "Bend Or" is most probably that of "Tadcaster". So the Conan-Doyle story "Silver Blaze" seems to be based on a suitably Sherlockian mystery that really occured.

Almost unbelievably there is another link between Grosvenor and Conan-Doyle, in that Conan-Doyle was a heavy investor in the attempt to find the "Grosvenor Treasure" - reputedly lost with the ship of the same name off the coast of the Transkei in 1782. It does not appear that the ship itself had any connection with the Grosvenors or with Chester, but the fabled treasure was the subject of many schemes after about 1880, some of which appear to have been scams and the name of the ship was of great help in raising money.

In 1899, the last year of his life, Hugh Grosvenor supported the "Seats for Shops Assistants" Bill (to reduce cruelty to women employees), stalked a stag in Scotland, shot 65 snipe in 1½ hours in Aldford on his Cheshire estate, and attended the wedding of one of his granddaughters. Later that year, while visiting the same granddaughter in Cranborne, Dorset, he developed bronchitis, from which he died. He was cremated in Woking Crematorium and his ashes were buried in the churchyard of Eccleston Church, Cheshire. He was succeeded as Duke of Westminster by his grandson, Hugh. At his death he was "reputedly the wealthiest man in Britain"; his estate for the purposes of probate was £594,229 (£58.4 million as of 2015).

sources and links

- Silver Blaze;

- The Mystery of Bend Or;

- TRUTH IN THE BONES: RESOLVING THE IDENTITY OF THE FOUNDING ELITE THOROUGHBRED RACEHORSES;

- How it affects the pedigrees;

- Cambridge University Website;

- More on Fred Archer;

- Legends of the Turf;

- THE SCROPE AND GROSYENOR CONTROVERSY;

Norman de l'Aigle Grosvenor

Norman de l'Aigle Grosvenor (22 April 1845 – 21 November 1898) a younger son of Robert Grosvenor, 1st Baron Ebury was returned to parliament at an unopposed by-election in December 1869, succeeding his cousin Hugh Lupus Grosvenor, who had succeeded to the peerage. He did not stand again at the 1874 general election. He was the last of the Grosvenor's to sit in the Commons as an MP for Chester.

By abandoning their hotly disputed claim to both seats in 1829, the Grosvenor family strengthened a widely acknowledged right to one of them, which was unchallenged by Liberal factions and Tories alike. Robert Grosvenor sat from 1832 to 1847, when he was replaced at an uncontested byelection by his nephew Hugh, Earl Grosvenor. The latter remained MP until he succeeded his father as marquess of Westminster in 1869, when in another uncontested byelection he was followed by his cousin Norman Grosvenor. The family's first partner at Chester was the lawyer John Jervis, knighted as attorney-general in 1846, who left the Commons in 1850. He was succeeded by W. O. Stanley, son of Lord Stanley of Alderley, who sat until 1857, when he was replaced by a local businessman, the Radical Enoch Salisbury. Although the Grosvenors per se withdrew from the seat in 1874, when the Liberal candidates were the senior party politician J. G. Dodson and one of the local leaders, Sir Thomas Frost, in 1880 they came back, partnering Dodson with the first duke of Westminster's nephew Beilby Lawley. Extensive treating and bribery were undertaken by both parties in 1880 in a campaign also marked by mob violence in the streets, directed especially against the Independent candidate. Salisbury, Walker, and the candidates resigned from the Liberal Association in order to conduct it more discreetly. The result of the election was a comprehensive Liberal victory. The Conservatives immediately petitioned against the result; after a short hearing in Chester had uncovered much evidence of corruption, the MPs were unseated and the matter was referred to a Royal Commission which exonerated the candidates but imposed a seven-year disqualification from voting on 914 individuals who had given or received bribes or treats. Chester was left unrepresented in parliament until 1885.

Sources and Links

Hugh Richard Arthur Grosvenor, 2nd Duke of Westminster