Saxon

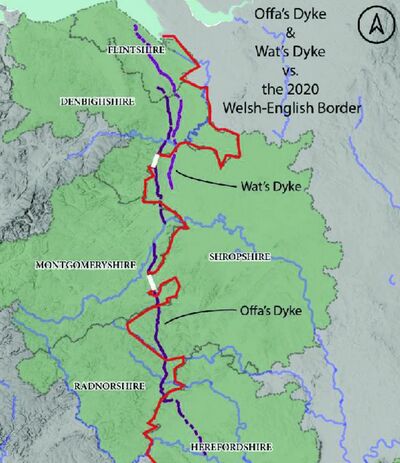

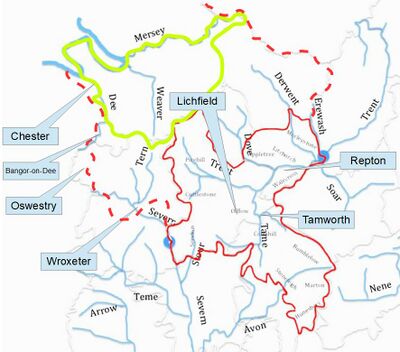

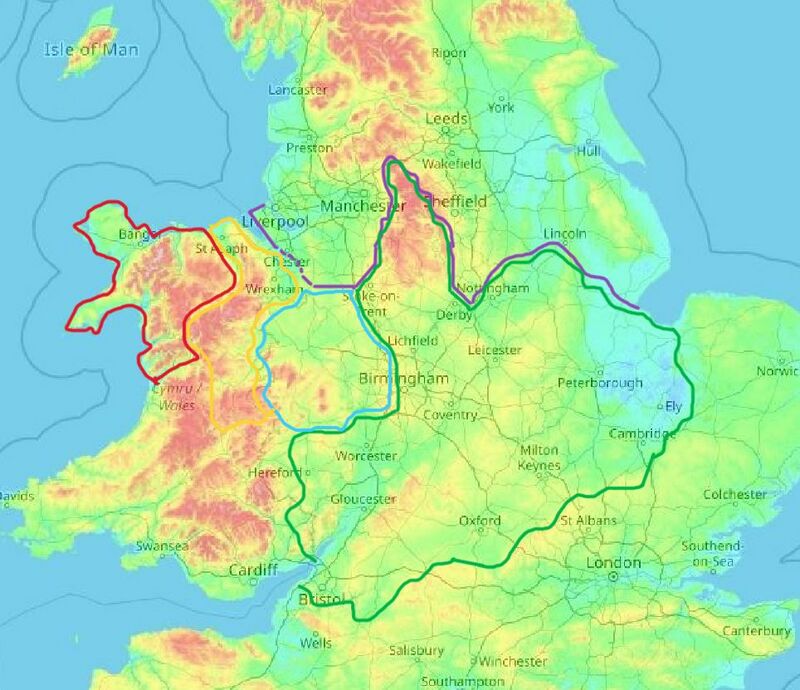

In Chester, one of the most obvious relics of its history is that the language used is in almost all cases English. At first glance everything is named in the Anglo-Saxon tongue or, rather, the modern English which derives from it. There are some exceptions, such as the name of the River Dee which is said to derive from the Brythonic dēvā: "River of the Goddess" or "Holy River", but most other things have Anglo-Saxon names. The local accent is nowadays a fairly neutral English with few overtones of Welsh, Liverpool or Lancashire occasionally heard. These language features are "landscape history" elements as important as Roman Roads, City Walls and Offa's Dyke in both the common perception of history and the academic study of it. So when, how and why was English first spoken in Chester?

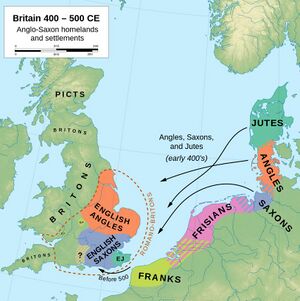

The post-Roman transformation of lowland Britain was profound. The end of the Roman administration in fifth century Britain preceded a dramatic shift in material culture, architecture, manufacturing and agricultural practice, and was eventually followed by a significant language change. This was the advent of the Anglo-Saxon culture in Britain. The archaeological record and place names indicate shared cultural features across the "North Sea zone", in particular, along the east and southeast coasts of present-day England, Schleswig-Holstein and Lower Saxony (Germany), Frisia (Netherlands) and the Jutland peninsula (Denmark). Examples include the appearance of Grubenhäuser (sunken feature buildings), large cremation cemeteries and the styles of cremation urns or objects that used animal art and chip-carved metal. Moreover, wrist clasps, as well as cruciform and square-headed brooches, found in sixth and seventh century Britain attest southern Scandinavian origins. The advent of the Saxons cannot be doubted. However, to this day, debate continues over the scale of migration, the mode of interaction between locals and newcomers, or how the transformation of the social, material, and linguistic or religious spheres was achieved.

By their presence, the Romans had already brought about much change. The pre-Roman British had nothing in the way of large urban centers. Even hill-forts may have only served as meeting places and shelters in times of strife. One of the first things the Romans did was to involve the conquered tribes in the administration of the province. They set up administrative centres according to traditional tribal territories and involved the tribal aristocracies in the decision-making (and tax-collection) process. The way to prestige and social advancement was through the Roman bureaucracy. So when the Romans built towns the ruling class of Celtic aristocrats built town dwellings. Town life was a social revolution for the largely rural Celtic society. Joining the towns together were the Roman roads. Over the course of the occupation, the Romans built over 9600 kilometres of roads in Britain. They were well built, and made troop movement and later the movement of commercial goods much easier. Away from these roads and towns the lot of the indigenous population was mostly unaltered. Most people living in the countryside stuck to their old Celtic languages and ways.

As compared with the North Sea zone the Irish Sea zone is distinct. It is accepted that at some time after the Romans departed from Cheshire, the Anglo-Saxons arrived and started to settle in this west-coast region. This article looks at post-Roman settlement process as applied to Cheshire and what would become the surrounding counties including Flintshire, South Lancashire and Shropshire. It does not consider the Vikings in detail as theirs was a colonisation period at a somewhat later time.

The transition from the Romano-British period to the Anglo-Saxon period is sometimes known as the "Age of Arthur" with reference to the legendary King Arthur. In some ways this is apt because many of the "historical" sources are barely distinguishable from myth. In many cases it is now clear which elements of folklore are derived from myth and which from history. However there is a complex "grey area" between the two which exists for many reasons and is a fascinating study in itself. The last ten years has seen much revision of the nature of the Roman occupation and it is now understood that earlier models of the Roman occupation of Britain in general were to some extent influenced by ideas related to later colonisation in the ages of Sail and Steam. Britain is no longer seen as "Romanised" below the Foss Way and militarised to the north and west of it. The Romans had no policy of imposing their culture on others much beyond the needs of tax-collecting and provided there was no open revolt, and that taxes were paid, the natives could carry on much as they had before. There were some minor exceptions to this as the Romans objected to actual human sacrifice (which they may have wrongly believed the Druids performed) or cannibalism (which they believed the christians did symbolically).

Much remains unclear as to when the Saxons first settled in Cheshire amd when Chester became an "English" town. For this, and many related questions is is not possible to give a definitive conclusion, so this article is more about issues, debates and resources than answers. To illustrate some of these issues with reference to the local, consider the following:

- The Battle of Chester c.616 was almost certainly fought at Heronbridge on Welsh (i.e. British) teritory against the Northumbrian English, but there is uncertainty as to who was fighting on the Welsh side and whether other English were involved as allies of the Welsh;

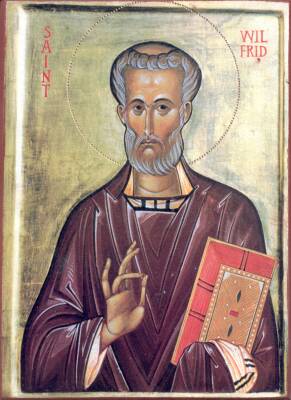

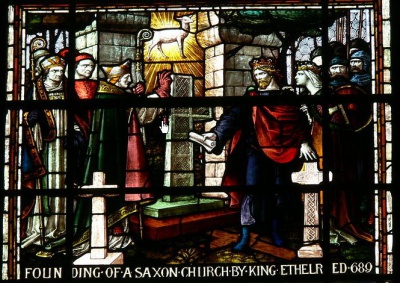

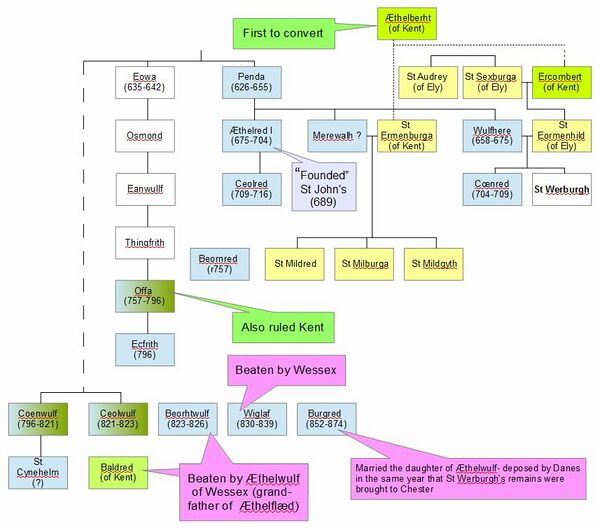

- Tradition and later stained-glass and signage, ascribes the foundation of St Johns to Æthelred, king of English Mercia (674–704), in 689;

- Coastal Wales along the Dee Estuary must have been under Mercia’s control through 821, as Coenwulf is recorded dying peacefully at Basingwerk, in Flintshire, in that year;

- West-Saxon Ecgbert is said to have raided/conquered Chester in c.830 when it was Welsh. The episode is shown in sculpture at the [[Town Hall];

- In 875 the remains of Werburgh are brought to Chester for safe-keeping: several early Anglo-Saxon characaters appear on her much later shrine in the Cathedral. Plegmund, a Mercian, may have been living here at the time;

If we believe the exploits of Ecgbert then Chester has changed hands between the Anglo-Saxons and the Welsh several times and a simple view that at some single point in time the Anglo-Saxons arrived in Chester is wrong. Unfortunately, finding clarity can be difficult. The archaeology is sparse and the few written sources may exhibit some bias. It is also worth noting that as of the time of writing some of the Wikipeda references linked to in the text contain errors or assume that folklore is 100% historical fact.

Brythonic and Saxon

The Brythonic languages (also Brittonic or British Celtic; Welsh: ieithoedd Brythonaidd/Prydeinig; Cornish: yethow brythonek/predennek; Breton: yezhoù predenek) form one of the two branches of the Insular Celtic language family; the other is Goidelic. It comprises the extant languages Breton, Cornish, and Welsh. The name Brythonic was derived by Welsh Celticist John Rhys from the Welsh word Brython, meaning Ancient Britons as opposed to an Anglo-Saxon or Gael.

The Anglo-Saxons came to Britain from North Germany and Southern Scandinavia in the 5th century. Old English developed from a set of Anglo-Frisian or Ingvaeonic dialects originally spoken by Germanic tribes traditionally known as the Angles, Saxons and Jutes. They crossed the North Sea in search of new land and prosperity. The date and manner of the arrival of the "Saxon" culture in Britain is expected to vary with place. Early theories proposed that the "Anglo-Saxons", who were a diverse group, either displaced the existing population westwards or exterminated them, eventually establishing a common "English" cultural identity. This article refers to them collectively as "Saxons" as it is difficult to define sub-groups using material culture.

Fled or Dead

The few surviving literary sources, such as Gildas a Welsh Briton, tell of hostility between incomers and natives. None were written in Britain at the relevant time. They describe violence, destruction, massacre, and the flight, extermination or enslavement of the Romano-British population:

- "In this way were all the settlements brought low with the frequent shocks of the battering rams; the inhabitants, along with the bishops of the church, both priests and people, whilst swords gleamed on every side and flames crackled, were together mown down to the ground, and, sad sight! there were seen in the midst of streets, the bottom stones of towers with tall beams cast down, and of high walls, sacred altars, fragments of bodies covered with clots, as if coagulated, of red blood, in confusion as in a kind of horrible wine press: there was no sepulture of any kind save the ruins of houses, or the entrails of wild beasts and birds in the open.."

None of the early sources relate to the northwest and Gildas in particular may be writing in the south of Britain (modern south Wales) and of events in the southeast a century after they occurred.

However, comparatively little clear evidence exists for any significant influence of British Celtic or British Latin on the incoming Old English language. That does not mean that there was no linguistic influence simply that it has not been identified. These factors have suggested to some a mass influx of Germanic-speaking peoples. In this view, held by many, including historians and archaeologists until the mid-to-late 20th century, much of what is now England was simply cleared of its prior inhabitants, who either left, became enslaved, or perished. Historical examples of this "genocide" or "ethnic cleansing" form of colonisation include extremes such as Tasmania, where the indigenous population was brought to near extinction. Victorian writers such as Charles Kingsley were fervent "Anglo-Saxonists" and their writings are much coloured by these beliefs. Anglo-Saxonists in the 19th century often sought to downplay, or outright denigrate, the significance of both Norman and Celtic racial and cultural influence in Britain.

This "sudden conquest" theory was still being taught in many UK schools well into the 1970's.

An immediate difficulty with the most extreme "fled or dead" hypothesis is that any invader wipes-out the means of food production and quickly needs to import agricultural workers to replace it. A further problem with Gildas description of how body parts littered the streets of devastated towns, and how many of those who attempted to flee were "murdered in great numbers", is that there is no archaeological evidence for this. It has been argued that in the period from 400 to 600, only about 2% of the human remains uncovered showed signs of death from a bladed weapon, and there are no mass graves. However these figures need to be treated with caution: removing women and children from the number could raise the figure to 5-10%. In addition to this, many of the men involved in battles would have died on the battlefield and been left to rot or to be eaten by animals. The rate of conquest can be compared with the Roman invasion, which started with the landing of Claudius in 43. By 47 it is likely that an area south of a line from the Humber to the Severn Estuary was under Roman control. Gaius Suetonius Paulinus mounted a successful campaign across North Wales, famously killing many druids when he invaded the island of Anglesey in 60. Final occupation of Wales was postponed however when the rebellion of Boudica forced the Romans to return to the south east in 60 or 61. Lead ingots from Deva Victrix indicate that construction there was probably under way by AD 74. Thus the Roman conquest was more rapid than that of the Anglo-Saxons anddd probably violent but does not provide the "mass graves with stab wounds" whose absence has been taken as a lack of violence in the Anglo-Saxon conquest.

Archaeology has shown that field layouts generally continued uninterrupted through the early period of the Anglo-Saxon migration and manufacture of types of pottery unknown to the Anglo-Saxons continued.

Gildas was writing (possibly 510-530) just before, or in the very early years of, a new burst of Anglo-Saxon expansion. He makes it clear that the British had fought back against the Saxons and he notes that there has been a period of comparative quiet during his lifetime, that further incursions by the Anglo-Saxons had largely paused and implies that the Britons in the west were living in peace against outsiders. However Gildas has the Briton's squandering this period of peace with civil war, internal disputes, and general unrest. He implies that this cannot last. The next major Saxon campaign against the Britons (in the south) was to not occur until around 577. Thus, Gildas is writing a century after the Anglo-Saxons had arrived in Britain but a century before they arrived in Cheshire.

Less Violent Change

Another view is that the migrants were fewer in number, possibly centred on a "warrior elite" which colonised in the manner of the Romans, Normans or perhaps the British in India. This hypothesis suggests that the incomers somehow achieved a position of political and social dominance, which, perhaps aided by intermarriage, initiated a process of acculturation of the natives to the incoming language, sometimes religion, and material culture. Archaeologists might therfore find that with the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons in England settlement patterns and land use would show no clear break with the Romano-British past, though changes in material culture could be profound.

A third view lies between the two extremes described above. The "warrior elite" are instead a culturally distinct group who introduce, for example, some new innovation in technology or agricultural practice, or a new religion, which spreads to the indigenous population and leads to a change in society. This could be a very small group of "incomers" or even occur through trade. An example would be where indigenous high status groups adopt elements of an "incoming" culture which they percieve as superior. However it could be a much larger group where the land could support a larger population than was presently upon it.

The replacement of one culture by another has often led to divisive arguments as to whether these are invasions, migrations or simply the effects of trade. German and Slavic scholars speak of "migration" (see German: Völkerwanderung, Czech: Stěhování národů, Swedish: folkvandring and Hungarian: népvándorlás), aspiring at times to the idea of a dynamic and "wandering Indo-Germanic people". In contrast, the standard terms in French and Italian historiography can translate to "barbarian invasions", or even "barbaric invasions" (French: Invasions barbares, Italian: Invasioni barbariche).

There are other explanations as to why land became empty and others might recolonise. A remarkable first-millennium population trend was the severe drop of population numbers immediately after (the heyday of) Roman occupation. Settlement evidence (largely qualitative) from different European regions suggests "a radical thinning out of … habitation sites during the 5th and 6th centuries". A c.12% decline can be inferred between AD 1 and 500 for the whole of Europe. Rough estimates provide a much larger c.35% decline between 500 and 650. Reasons put forward for this include war, economic collapse, climate change and disease. Work by dendro-chronologists and ice-core experts points to an enormous spasm of volcanic activity in the 530s and 540s, unlike anything else in the past few thousand years. This violent sequence of eruptions triggered what is now called the "Late Antique Little Ice Age", when much colder temperatures endured for at least 150 years. This co-incided with the Plague of Justinian (see: Pandemic). The Ecclesiastical History of Bede, notes the plague of 664: the only epidemic in early British annals that can be regarded as a plague of the same nature, and on the same great scale, as the devastation more than a century earlier. Bede wrote:

- "In the same year of our Lord 664, there happened an eclipse of the sun, on the third day of May, about the tenth hour of the day. In the same year, a sudden pestilence depopulated first the southern parts of Britain, and afterwards attacking the province of the Northumbrians, ravaged the country far and near, and destroyed a great multitude of men."

Earlier plagues might have affected the Romano-British differently than the as yet unmigrated Saxons. For example if they spread along Roman trade routes then they might never reach the Saxons.

This article is particularly concerned with events which potentially had a local impact in the Cheshire area, but given the scarcity of local evidence from the period it is useful to look at a wider geographical scope. Sometimes these would have parallels in Cheshire but in many cases there are reasons for thinking they do not. As would be expected any local situation might well be a mixture of the above processes and occur at differing times and timescales, although general education has tended to present the departure of the Romans and the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons as a single national process. Some of the factors which could influence matters on a local scale are discussed below.

Issues

The idea that "the Romans left around 400, then the Anglo-Saxon arrived" is now hardwired into the public consciousness. It can be considered a very "south eastern" view of the post-Roman transition. A slightly more elaborated version adds "..and the British Isles were pagan until Augustine arrived around 600". Neither of these statements is true.

Assuming that the Anglo-Saxons arrived on the south and east coasts of Britain, the above model becomes increasing weak as one moves north and west. In Cheshire and the surrounding area the same model cannot be expected to apply as it would require a very rapid conquest by relatively small forces. The following issues can be considered:

- The End of Roman Britain: What should be considered the "End"? - is it the departure of the legions, the expulsion of magistrates appointed by the "Romans", the end of any hope that aid could come from the continent, the development of local institutions such as the church, or the displacement of the "Romano British" from power?

- Cheshire: What does what later became "Cheshire" mean in this context? Who ruled it, where were they based, and how far did their rule extend?

- The "Decline and Fall" Paradigm: When did the Saxons actually arrive in Cheshire and did they migrate or invade?

- Segontium: Did this significant Roman fort on the Menai Strait remain occupied and if so by who. Did this have any regional influence?

- Vortigern: Who was he and why does he have an actual association with North Wales and any special influence on the Cheshire region?

- Gwynedd, Powys and Pengwern: How did these Roman "sucessor states" come about and how did they interact with "Cheshire"

All these issues can be examined in the light of the scant literary evidence as originally interpreted to indicate mass-migration and displacement, the later theories of "a warrior elite" or the most recent "hybrid" view. Some care is needed as it is all too easy to "bust" one myth and replace it with another.

The End of Roman Britain

Ostorius Scapula launched a campaign against the Deceanglii, possibly as early as AD 48. Suetonious Paullinus mounted three campaigns in Wales in AD 58-60, perhaps utilising the Dee Estuary; the last of these reached Anglesey, although the success of the campaign was halted by the Boudican revolt. It was Julius Agricola who finally subjugated north Wales during his first campaign in AD 78. A fort may have been established at Roman Chester by Paullinus, although this remains to be confirmed, while the construction of a legionary fortress here commenced in AD 74. As noted above, there is no physical evidence that this subjugation was violent, but the Romans were not known for their peaceful conquest.

The general consensus of archaeologists is that Roman Britain reached its peak of prosperity in the early 4th century. However, near contemporary writers can give a different impression, showing the the local administration was at times in revolt against Rome. The western Caesar Constantius Chlorus needed to re-establish Imperial rule in Britain following a revolt by Carausius (a Roman Naval commander in Britain) and later Allectus (defeated 296), his finance minister and eventual assassin. Eutropius (fl. AD 363–387) writes of the English Channel being cleared by Carausius, since the Armorican and Belgian coasts had been 'infested' with Francs and Saxons. After his father's death in 306, Constantine was acclaimed as augustus (emperor) by his army at Eboracum (York). He eventually emerged victorious in the civil wars against emperors Maxentius and Licinius to become the sole ruler of the Roman Empire by 324. St Jerome famously described Britain as "a province fertile in tyrants (fertilis provincia tyrannorum)" (Jerome, Letters vol. 56, no. 133.9.13) — the military usurpers who can be seen in hindsight as milestones on the road to ruin for Roman Britain.

Following the revolt of Magnentius, Paulus "Catena" was dispatched to Roman Britain in 353 by the paranoid Constantius II to exact savage reprisals against supporters of Magnentius in the army garrisons of Britain. These "revolts" appear to have only involved the army.

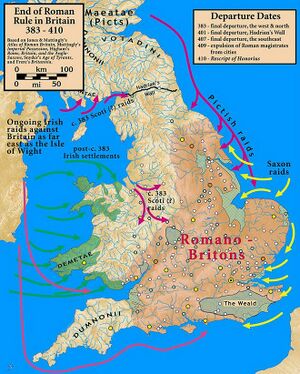

In the winter of 367, the Roman garrison on Hadrian's Wall supposedly rebelled and allowed Picts from Caledonia to enter Britannia. This has become known as part of the "Great Conspiracty". In the spring of 368, a relief force commanded by the elderly Flavius Theodosius arrived in Britannia from Gaul. He brought with him Magnus Maximus, who, when later assigned back to Britain would himself revolt in 383. It was once thought that Maximus stripped troops from Hadrian's Wall to support his revolt. Coins dated later than 383 have been excavated along Hadrian's Wall, suggesting that troops were not stripped from it. In Welsh tradition however, Magnus Maximus is the last of the Roman rulers of Britain.

There may have been one more attempt to shore-up Roman Britain. Claudian's de consulatu Stilichonis, (2, 250-5), written in January 400 is possible (but weak) evidence for an expedition to Britain mounted by Stilicho in 396-8 to deal with "external" threats. There is no supporting evidence. The Notitia Dignitatum, a list of officials probably compiled c. 400, mentioned neither troops at Chester nor the Twentieth Legion elsewhere in Britain. It could well be that "central" Roman authority in the Cheshire region had partly or largely collapsed by this time. On the other hand, the concept of Magnus Maximus as the the "last Roman ruler" could be an invention to support Welsh pedigrees created much later.

The crossing of the Rhine River by a mixed group of barbarians which included Vandals, Alans and Suebi is traditionally considered to have occurred on the last day of the year 406 although 405 fits better with events in Britain. It initiated a wave of destruction of Roman cities and the collapse of Roman civic order in northern Gaul. Thereafter the provinces of Britain were isolated, lacking support from the Empire. That some legionary troops remained even then is evidenced by the setting up and pulling down of a final series of usurper emperors as the soldiers supported the revolts of:

- Marcus (406 - 407), a soldier in Roman Britain who was proclaimed emperor by the army there some time in 406. All that is known of his rule is that he did not please the army, and was soon killed by them;

- Gratianus (407), acclaimed as emperor by the army in Britain in early 407. His army wanted to cross to Gaul and stop the barbarians who were attacking the empire but Gratian ordered them to remain (he should have known better). Unhappy with this, the troops killed him - and finally;

- Constantine "III" (who actually listened to the troops). Constantine III was a British common soldier and invaded Gaul in 407, eventually occupying Arles, but in the process possibly drained Britain of the last of it's Roman legions. Possibly 6000 mobile troops. He had some limited success, but in 411 Gerontius besieged Constantine in Arles and killed him.

Later writers, particularly Geoffrey of Monmouth (c.1095 – c.1155), make these usurpers "Kings of Britain" and use them as a largely fictitious historical narrative.

How we get this information illustrates some of the problems with with sources. Details of these three usurpers come from Bibliotheca of Photius in the ninth century, who states that these are fragments from Olympiodorus of Thebes who was a Greek pagan historian from Thebes in Egypt and published his now lost account shortly after 425.

Around 410, the Romano-British expelled the Roman "magistrates" from Britain. A frequently used "endpoint" for Roman Britain is often assumed to be the so-called "Rescript of Honorius" of 411 when the emperor reputedly told the British cities to look after their own defence. This interpretation has been questioned. Honorius was fighting a large-scale war in Italy against the Visigoths under their leader Alaric, with Rome itself under siege. No forces could be spared to protect distant Britain, alhough it is possible that Honorius expected to regain control over the provinces soon. On the other hand Britain did not pay the complete costs of occupation, yet nevertheless, the Romans were forced to keep three or four legions, 30,000 to 40,000 men with auxiliary units in place to defend it. History had already shown, several times, these legions would be a considerable benefit to any local usurper.

Britain appears to have suffered a "system collapse" at the end of Roman rule. The markets (urban centers and the military garrisons) dissappeared, as did the means of production (villa farm estates). Coinage dried-up and the money economy halted as taxation collapsed and state-sponsored transport ended. One of the mainstays of archaeology, pottery, ceased to be produced on an industrial scale. Historians tend to be rather polarised in their views on the nature and timing of this Roman "system collapse". Some consider it was very rapid and chaotic possibly with revolts of slaves or Germanic mercenaries already in place. Others see it as a more gradual transition. The anonymous author of De Vita Christiana, who may have been a Pelagian and possibly even a Briton, wrote in the early fifth century:

- Of these some, who had frequently shed the blood of others, felt the wrath of God to such effect that they were compelled at last to shed their own. ... Others who had committed similar deeds were so completely overthrown by the wrath of God that their bodies lay unburied and became food for the beasts and the birds of the air. Yet others who had unjustly destroyed a countless multitude of men have been torn to pieces limb from limb, piece by piece...

This may well be violence associated with any one of the fall of Constantine III, the ejection of the Roman administration, or the rapid collapse of the economy based on taxes public spending. Such violence could well have been widespread, but is nothing to do with the Saxons as it was perpetrated by the British themselves.

The above summary implies that Britain as a whole had a somewhat insecure government towards the end of the Roman period, but these historical facts are largely concerned with military affairs at a national level. Much less is known about other institutions, such as the church, and especially in some specific geographical locations, such as Cheshire.

Not all regions in Roman Britain were governed in the same manner. It was once thought that some had a strong element of civilian control (those in the south-eastern "lowland" zone) whereas others were essentially military (those in the northern and western "highland" zone). This view has been recently criticised. City-based local government, was governed by a town council (curia), led by elected magistrates. They were responsible for settling local disputes and collecting taxes from the population in the extensive surrounding territory, and passing them on to the state. There were 22 major towns in Britain. Seventeen of them were civitas capitals based on the tribal areas (civitates) into which the Britons had been organised in the course of the conquest. It has been suggested that the civil settlement at Chester was elevated to the status of civitas capital of the northern Cornovii at the end of the 2nd or early 3rd century under Septimius Severus, but there is no conclusive evidence for this.

The early christian church in Roman Britain was largely based in towns (as were Bishops) and posssibly appealed mostly to the wealthier and better educated classes. There is little evidence for an organised Celtic church of unique in character with its own structures and practices, especially in north Wales, at the time of the departure of the Romans. The British Bishops considered themselves part of the Roman Church. Participation by a British bishop at a synod in Gaul demonstrates that at least some British churches were in full administrative and doctrinal touch with Gaul as late as 455. Most of the surviving "lives" of the early Welsh "saints" were written from an eleventh or twelfth century perspective and it is uncertain whether these can provide any historical background. The earliest of these saints including Dubricius lived in the 6th century.

Elsewhere

The accession of Honorius and his brother Arcadius in 395 was marked by a basic change in the role of the emperor. After holding the consulate at the age of two in 386, Honorius was declared augustus by his father Theodosius I, and thus co-ruler, on 23 January 393, after the death of Valentinian II and the usurpation of Eugenius. When Theodosius died, in January 395, Honorius and Arcadius divided the Empire, so that Honorius became Western Roman emperor at the age of ten. During the early part of his reign, Honorius depended on the military leadership of the general Stilicho, who had been appointed by Theodosius and was of mixed Vandal and Roman ancestry. To strengthen his bonds with the young emperor and to make his grandchild an imperial heir, Stilicho married his daughter Maria, to him. Stilicho's downfall came in 408, when, following his inability to deal with the rebellion of Constantine III, he was executed. Thereafter, the Roman military were pre-occupied with continental events and only the continental church was in any position to send "aid" to Britain.

Cheshire

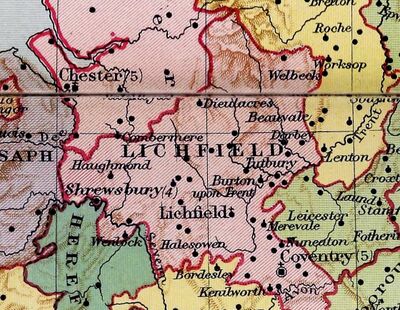

As noted above this article attempts to look at Anglo-Saxon settlement in Cheshire and other associated cultural exchanges in the same region. This is a particularly interesting problem due to Cheshire not only having a land and linquistic border with Wales but also by it being a port of the Irish Sea zone. Matters are complicated by the fact that Cheshire was the location of a major Roman base which may or may not have had a cultural legacy. It has been suggested that the civil settlement at Chester was elevated to the status of civitas capital of the northern Cornovii at the end of the 2nd or early 3rd century under Severus, but the evidence on this is inconclusive. In order to try to discover how Cheshire transitioned from Roman to Anglo-Saxon a number of different sources of information can be consulted.

Cheshire is an area arbitrarily defined to serve modern administrative needs. The borders of what is now termed Cheshire are in part defined by landscape features mostly involving the Cheshire Plain. Cheshire occupies a fertile double basin of undulating lowland divided from the rest of the Midlands by the barriers of the southern Pennines and a low, but historically significant ridge of glacial and post-glacial sands which helped to divert the post-glacial drainage of North Shropshire to the Severn and so isolated Cheshire drainage from that of the neighbouring lowlands to the south. To the west and north the rivers Dee and Mersey roughly follow the boundary and between them around the Wirral the boundary follows the mostly estuarine coast. To the east the Pennines form a natural geographic border. Between Shocklach and Whitchurch the Wych Brook (formerly the River Elfe) roughly defines a convenient boundary. Of course this has not always been the cultural boundary: at times parts of Flintshire were under control of the "English" side and at other times Chester appears to have been under Welsh control. As H. J. Hewitt has said (Mediaeval Cheshire (1929), p150):

- "the Earldom (of Chester) which marked the early limits of Norman power, marked also broadly the limit of Saxon invasions."

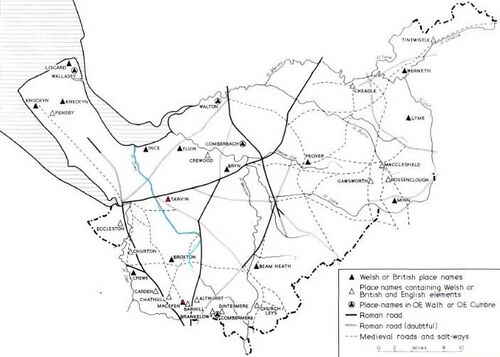

Even in late Roman Chester historical information is difficult to come by. There is little by the way of written evidence for the period 400-700, so determining the date of the arrival of "Saxon" culture is difficult. Archaeology, which is largely concerned with artifacts, provides little information. Cheshire does not have the Pagan Saxon archaeology of eastern England. What Cheshire does have is a confusing mixture of English place-names with a remarkably low survival of Celtic names, strong hints of Celtic Christianity in ecclesiastical organisation and evidence for early territorial organisation which appears to extend back to the Roman past. There is also an increasing body of information from genetic information. Recent "ancient DNA" results show that around 75 percent of the ancestry of individuals in Eastern and Southern England was shared with those from continental regions bordering the North Sea, including the Netherlands, Germany and Denmark.

There is no detailed historical record of the Roman legions packing up, blowing out the lights, marching out of Chester and leaving the local populace to their own devices. Indeed, after over three-hundred years of "occupation" the Romans were probably pretty well integrated with the indigenous population. Coin finds on the Wirral seem to suggest that retired Roman soldiers lived a settled life in the area. If they did they may well have taken local wives. They probably even spoke the local language. The most likely scenario was that regular troops were withdrawn to support civil wars in mainland Europe, leaving local irregular troops, retired veterans or mercenaries to defend the Roman towns as best they could. There were frequent appeals to Rome for help, few of which were answered, although some were. There are also some historical hints of the survival of Roman culture in the area around Chester: 1.5km to the north-east of Tarporley, at Easton, is the only known and excavated Roman Villa in Cheshire (there may be a further villa near Saighton). The evidence from Eaton suggests occupation into the early 5th century.

Just when the Saxon's first became a potential problem for the Brythonic-speaking Roman British is not clear, but the title "comes littoris Saxonici per Britanniam" ("Count of the Saxon Shore") was possibly created during the reign of Constantine the Great (306-337), and was probably in existence by 367 when Nectaridus is elliptically referred to as such a leader by historians such as Ammianus Marcellinus. Obviously, the "Saxon Shore" is that to the south and east of England, and there is no reason to suppose that the Saxons frequently sailed into the Irish Sea. However there were Roman coastal defences on the north Wales coast intended to protect against the Scots, Picts and others from around the Irish Sea.

Wroxeter

Wroxeter has a quite different set of archaeology to Chester. It is known to have been the site of extensive civilian activity until well after the departure of the Romans.

Wroxeter was first established in the early years of the Roman conquest of Britain as a frontier post for a cohort of Thracian Auxilia who were taking part in the campaigns of the governor, Publius Ostorius Scapula (died 52). A few years later a legionary fortress (castrum) was built within the site of the later city for the Legio XIV Gemina during their invasion of Wales. By the late 80s the fort had ceased to be used by the Roman army after Legio XX Valeria Victrix moved to Deva Victrix. In this period the canabae, or civilian settlement, that had grown up around the legionary fort began turning it into a town. Of this town much survives and it has been extensively studied.

During the rest of the Roman period the town was the administrative center of the Cornovii. The "First Cohort of Cornovi" was the only regiment of native British troops known to have been stationed in Britain itself. The unit is mentioned only in the Notitia Dignitatum and apparently formed the late-fourth century garrison at Pons Aelius, an auxiliary castra on the site of the castle at Newcastle-upon-Tyne, the original eastern terminus of Hadrian’s Wall. Several theories attempt to link Wroxeter into the creation of sub-Roman successor states such as Powys and the semi-mythical polity of Pengwern.

At Wroxeter, archaeological research has found that an unfinished legionary bath house in the centre of the town eventually became the town's forum. A decade later a civic street grid was subsuming the plan of the old legionary fort. At its peak, Viroconium is estimated to have been one of the richest and the fourth largest Roman settlement in Britain with a population of more than 15,000. Viroconium appears to have served as the early sub-Roman capital of Powys, variously identified with the ancient Welsh cities of Cair Urnarc or Cair Guricon which appeared in the Historia Brittonum's list of the 28 civitates of Britain. It should be noted that some older books appear to make Viroconium in post-Roman times a far more vibrant place than it actually was. Evidence for the foundation of the wealth of the town is not forthcoming but extensive mineral deposits of lead, silver and coal are located nearby and the Cornovii controlled three centres of salt production.

It is possible that the status of the town declined in the 4th century since the large and unwieldy territory of the Cornovii was possibly broken up into smaller units with Chester and Whitchurch being likely centres for the new pagi. Viroconium possibly became the site of the court of a sub-Roman "kingdom" known in Old English as the Wreocensæte, which was the successor territorial unit to Cornovia. Wrocensaete means the "the people sitting at the Wrekin" or "the people .. Wroxeter" and the boundary of their land has been the subject of much speculation, with some having it include much of Cheshire. The fact that the people have an Old English name does not mean that they were English - the name was what the English called them and they could be, and probably were, the Cornovii.

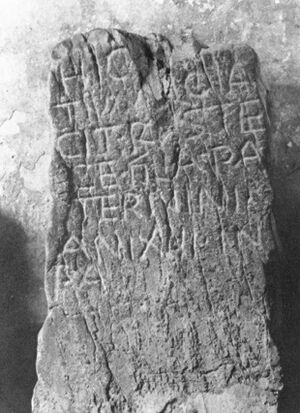

The ethnic origins of the inhabitants has also been the subject of speculation. The Wroxeter Stone or Cunorix Stone, was found in 1967, with an inscription in an Insular Celtic language, identified by the Celtic Inscribed Stones Project (CISP) at UCL as "partly-Latinized Primitive Irish". The inscription, probably on a re-used gravestone, is dated to 460-475 AD, when Irish raiders had (possibly) begun to make permanent settlements in west Wales and south-western Britain. It reads "CVNORIX | MACVSM/A | QVICO[L]I[N]E", traditionally normalised as Cunorix macus Maqui Coline and translated as Cunorīx son of Maqqos Colinī. "Cunorix" can itself be translated as "top dog"! Thus it is possible that Cunorix may be either one of a number of Irish foederati settled by the Romans in Wales or one of their descendants. It was common Roman policy in the later empire to settle a certain number of barbarian "invaders" within the boundaries of the Empire to ward off the rest. Irish settlers in Wales are known mostly from their tombstones, of which there are a considerable number. However these are chiefly concentrated in Pembrokeshire in the South West, and mostly written in the Ogham script. One must be wary of building an Irish Wroxeter upon a single gravestone.

The 5th century saw continued town life in Viroconium but many of the buildings fell into disrepair. However, between 530 and 570 there was a substantial rebuilding programme in timber with most of the old basilica being demolished and replaced with new wooden buildings. The infrastructure needed to transport stone for building-work had been lost. These probably included a very large two-storey timber-framed building and a number of storage buildings and houses. In all, 33 new buildings are said to have been constructed. Some of the buildings were renewed three times and the community possibly lasted about 75 years until for some reason many of the buildings were dismantled. Some sources state that Offa of Mercia (ruled 757 – 29 July 796) annexed the entirety of Shropshire over the course of the 8th century from Powys, with nearby Shrewsbury captured in 778. Other sources state that the likely date of abandonment of Wroxeter as an urban settlement seems to have been in the later 7th or the 8th century when, on place-name evidence, the Anglo-Saxons occupied the area. By both these dates the Mercians had already been converted to christianity. It seems unlikely that the town was ever completely abandoned since the church in the village (St Andrew) dates to the 8-10th century (estimates vary) and is associated with a 8/9th century cross-shaft.

Recent work on animal remains at the site show that through the 5th to 7th centuries, there is little evidence of major changes in animal husbandry. Whether for economic or for more symbolically-embedded reasons, the delivery of adult cattle into Wroxeter continued through the 5th-7th centuries, indicating some consistency in the structure and utilisation of the surrounding countryside. Wroxeter gives the impression that, at least in terms of animal husbandry and supply, life went on.

From sub-Roman times there is no evidence of any administrative or economic connection between Chester and Viroconium. The only link that can be suggested with any confidence is that if someone from the south-east were migrating or invading towards Cheshire then they would have to pass Viroconium both to reach Cheshire and to maintain communications with whence they came. Viroconium seems to have been unmolested up to the 7th century, so it is a safe bet to assume that at the time of the Battle of Chester Chester and probably most of Cheshire was in Welsh hands.

Decline and Fall Paradigm

Concerning Britain, the "Decline and Fall" paradigm holds that at the end of the Roman period Britain experienced a more dramatic collapse than other provinces in the Western Roman Empire: political and economic institutions disintegrated by the mid-fifth century or earlier; towns were abandoned; the Anglo-Saxons dominated late fifth-century Britain and conquered it in the sixth century. Until the 1970's it also appears that it was widely believed that christianity became extinct until the Augustinian mission in 597.

Gildas and Bede both present narratives that describe a dramatic collapse of society in Britain and do not emphasise continuity, this was taken as historical fact. However, they each had their own reasons for describing a large-scale systemic collapse. Gildas‘ purpose was to shock the religious and secular leaders of Britain into returning to what he considered acceptable standards of behaviour. Bede took advantage of Gildas‘ negative portrayal of the British to legitimise what he considered Anglo-Saxon political and cultural dominance over the Britons, especially as regards religion. The most frequently cited date for the end of Roman Britain under this paradigm is 410, a date much earlier than the traditional date for the end of the Western Roman Empire, 476. The former is also the date attributed to the letter from Honorius to the citizens of Britain advising them to look to their own defences. The Decline and Fall Paradigm held that the c200 years, 410-597, the bulk of the 5th and 6th centuries, was a period of decay, chaos, ignorance and paganism which only ended with the arrival of Augustine.

The "Late Antiquity" paradigm opposes such a catastrophic decline. Instead it proposes a transition including the spread of Christian monasticism. Christianity was well established in Britain by 400: Victricius of Rouen in his De Laude Sanctorum (396) explains that he has just returned from Britain where he was invited to settle a dispute between bishops. Monastic spirituality came to Britain and then Ireland from Gaul, by way of Lérins, Tours, and Auxerre. A monastery may have been established in Wales c450. A convenient endpoint for late antiquity in the region is possibly the Synod of Chester an ecclesiastical council of bishops held in Chester in the late 6th or early 7th century.

The early development of the above theories paid little attention to the lot of the common man, but were based largely on evidence relating to military and religious elites. They are also somewhat biased towards events in the south and west of Britain and therefore not reflective of what may have been happening, for example, on the Irish Sea coast. For some, such as tax-collectors, the "departure of the Romans" and the changes in the nature of the economy would have been a catastrophic change.

575-600

At the same time as the East Angles were being united under a single king, Angle and Saxon conquests were rapid and extensive, but mostly in the south of Britain and the north-east. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle the West Saxons defeated three British kings in c577:

- "577: Here Cuthwine and Ceawlin fought against the Britons, and they killed three kings, Coinmail, Condidan and Farinmail, in the place which is called Deorham, and took 3 cities: Gloucester and Cirencester and Bath"

This resulted in the capture of Caer Gloui (Gloucester), Caer Ceri (Cirencester), and Caer Baddan (a second Battle of Badon?). The Hwicce moved into new territory to form their own kingdom while the West Saxons continued to fight against Dumnonia resulting in the Battle of Deorham. The catastrophic British defeats in 577 meant that both Dumnonia and Caer Celemion were now totally isolated, while the East Saxons consolidated their own kingdom to the north of the Thames Estuary, possibly under Æscwine.

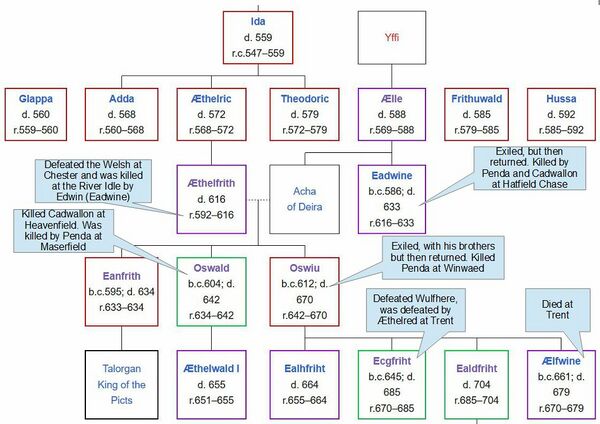

North of the Humber, the two Angle kingdoms were also making rapid advances. According to tradition Ebrauc's defence finally ran out of steam circa 580, which is when it was overrun by the Deiran Angles. The Bernician Angles appear to have destroyed the kingdom of the Peak around 595. Saxon groups moved in from the Midlands to adopt the name, becoming the Pecsaetan (Peak settlers). Æthelfrith (Æðelfriþ), united Deira with his own Bernician kingdom by force around the year 604.

Elmet was now surrounded by enemies but North Rheged was at the height of its strength, even controlling nearby Galwyddel (Galloway), until in-fighting, or the Northumbrians, brought down its powerful leader. In Wales however and over parts of the Midlands there was still a strong British presence.

The important take-out from this is that even at the time that Augustine was landing in Kent (c.600) on the sea-border of "England" many of the Anglo-Saxons had only recently formed and Mercia, Wessex and Northumbria still had room for expansion to the west. The church would be involved in this expansion into teritory where the Welsh/Celtic church previously had significant influence.

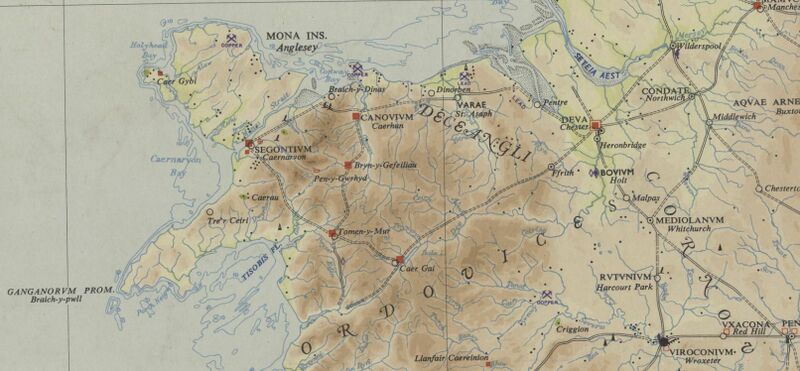

Segontium

Segontium (Old Welsh: Cair Segeint) is a Roman fort on the outskirts of Caernarfon in Gwynedd, North Wales. The fort, which survived until the end of the Roman occupation of Britain, was garrisoned by Roman auxiliaries. It was the most important military base and administrative centre in this part of northwest Wales. The fort may take its name either directly from the Afon Seiont or from a pre-existing British settlement itself named for the river. Alternatively, the name could be a Latinised form of the Brythonic language seg-ontio, which may be translated as "strong place", although given that "sego" means "vigorous" as applied to the river "place by the vigourous river" seems a better fit.

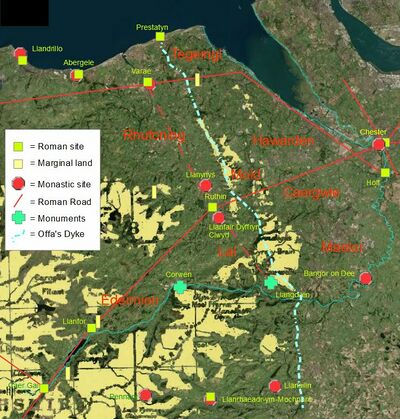

Segontium was founded by Gnaeus Julius Agricola in AD 77 or 78 after he had conquered the Ordovices in North Wales. It was the main Roman fort in the north of Roman Wales and was designed to hold about a thousand auxiliary infantry. It was connected by a Roman road to the Roman legionary base at Chester. An inscription on an aqueduct from the time of the Emperor Septimius Severus indicates that, by the 3rd century, Segontium was garrisoned by 500 men from the Cohors I Sunicorum, which would have originally been levied among the Sunici of Gallia Belgica. The size of the fort continued to reduce through the 3rd and 4th centuries although according to some sources coins found at Segontium show the fort was still occupied until at least 394. Other sources state that the latest coin from the site is that of Gratian (367-383).

At this "late Roman" time Segontium's main role was the defence of the north Wales coast against Irish raiders and pirates. It appears that a coastal defence network was constructed along the coast of North Wales, with a small fort at Caer Gybi (Holyhead) on Angelsey and a series of forts (Caer) and signal towers along the Welsh coast. Possible sites were at Hen Waliau (Caernafon), Aberffraw (possible), Bangor, Braich yr Dinas, Caerhun, Deganwy, Varis (St Asaph) and possibly also at Pentre. There are probably remains of watch-towers or signal-beacons which have yet to be found. The fact that the Romans should build so much infra-structure in north Wales raises the issue of what they were defending and the degree of "Romanisation" of the population between Segontium and Deva. This leads on to the issue of how long a Romanised way of life would have survived in the region.

There has been significant discovery of Roman industry near Flint, where metals (mostly lead) was processed at Pentre Ffwrndan: "the place of the firey furnace". LiDAR data has revealed a possible Roman fortlet (PRN 123918) around 1.3km north-west of Greenfield, located on the edge of higher ground, overlooking the coastal plain. Lead from the Flintshire orefields contains a relatively high proportion of silver which could be extracted by cupellation. This would have added considerably to its value, perhaps explaining the possible presence of a high-ranking Roman official at the Deeside settlement.

Irish "Invaders"

From the literature we see that for the Irish Sea region the initial foreign threat was the Scoti and possibly the Picts. Jones & Mattingly's Atlas of Roman Britain (1990) shows incursions of Irish invaders/settlers through Cheshire and shows significant Irish settlement in Angelsey and Dyfed. There are a number of sites, such as that at Ty Mawr, known as "Cytiau Gwyddelod", or "The Huts of the Irishmen".

Scoti or Scotti is a Latin name for the Gaels, first attested in the late 3rd century. It originally referred to all Gaels, first those in Ireland and then those in the rest of Great Britain as well, but it later came to refer only to Gaels in northern Britain. An early use of the word can be found in the Nomina Provinciarum Omnium (Names of All the Provinces), which dates to about AD 312. This is a short list of the names and provinces of the Roman Empire. At the end of this list is a brief list of tribes deemed to be a growing threat to the Empire, which included the Scoti, as a new term for the Irish. For the purpose of this article Scoti is taken to refer to Irish and particularly those who raided across the Irish Sea.

Matters are complicated by the fact that not everyone crossing the Irish Sea was a raider. In the late fourth century there was an influx of settlers into Wales from southern Ireland, the Uí Liatháin and Laigin (with "Déisi" participation uncertain), arriving under unknown circumstances but leaving a lasting legacy especially in Dyfed. Déisi is an Old Irish term that is derived from the word déis, which meant in its original sense a "vassal" or "subject", a designated group of people who were rent-payers to a landowner. As a class that evolved from peoples tied by social status rather than kinship, groups had largely independent histories in different parts of Ireland.

That people from Ireland settled in some numbers in western Wales about the fifth century is generally accepted. Physical evidence of the Irish presence in post-Roman Britain comes in the form of Ogham inscriptions. Some of these are dual-language which implies co-existence and co-operation. There is also a large legendary literature concerning the interaction of Ireland and Wales. However, the scale and duration of the Irish ‘colonization’, along with its influence on the native Brittonic population, remain a matter of debate. What documentary references to Irish incursions and settlement exist are difficult to exploit as they were all written much later, and subject to the vagaries of oblivion, omission and contemporary political propaganda. According to the ninth-century Historia Brittonum, the family of Eochu Liathán settled in the southern region of Wales until they were driven out by Cunedda and his sons. Later on, this same record refers to Cunedda and his sons driving the Irish out of the region which subsequently became the kingdom of Gwynedd:

- "Maelgwn, the great king, was reigning among the Britons in the region of Gwynedd, for his ancestor, Cunedag, with his sons, whose number was eight, had come previously from the northern part, that is from the region which is called Manaw Gododdin, one hundred and forty-six years before Maelgwn reigned. And with great slaughter they drove out from those regions the Scotti who never returned again to inhabit them."

There is the familiar linguistic problem here: the name Cunedda (spelled Cunedag in the AD 828 pseudo-history Historia Brittonum) derives from the Brythonic word *Cuno-dagos, meaning "Clever Dog" or "Having Good Hounds/Warriors". There is considerable doubt in the academic literature that the Irish settlement in north Wales was anything like as extensive as was once supposed, or that there was any significant migration from the Votadinii region. The material to back up a fifth-century Irish presence in northwest Wales is insubstantial, even in contrast to that for continuing local British elites. In total, it comprises a few ogham stones and Latin inscriptions containing Irish personal names - not even all fifth- rather than sixth-century in date. There are some medieval or later Irish place-names and there is post-medieval folklore.

Opinions vary greatly as to when (and if) Cunedda lived. Some place him in the 6th century whereas others grant an earlier date. Maelgwn Gwynedd (Latin: Maglocunus; died c. 547) was king of Gwynedd during the early 6th century, and according to some genealogies he was the great-grandson of Cunedda. The Historic Brittonum dates the migration of Cunedda precisely, and in unequivocal terms, as 146 years before Maelgwn Gwynedd reigned. Maelgwn probably succeeded to the throne in 534, and Cunedda therefore left Manau for Wales c 388, the year of Magnus Maximus’s defeat and execution. However the Historic Brittonum, refers to Cunedda as Maelgwn’s grandfather’s great-grandfather.

Vortigern

The period between the departure of the Romans and the settlement of the Saxons has been called the "Age of Arthur" after the legendary king. Records from the time are sparse but the name of Vortigern as an important character seemingly involved in events eventually emerges. Vortigern's existence is contested by scholars and information about him is obscure. Unfortunately, many online sources assume without any doubt that he was a real historical figure and fail to distunguish between sources which are historical, folklore, myth or fiction. It is also the case that many of the legends surrounding Vortigern are set in Wales. This does not automatically make him a "Welsh" character as his existence/legend may have simply been largely if not entirely forgotten in areas that were occupied by the Saxons. Vortigern and Cunedda both feature in the "traditional" version of the family trees of Welsh monarchs: a schema which may have been subject to political revision at various times.

The 6th century cleric Gildas does not mention Vortigern by name in most surviving editions, with only two later copies mentioning him. MS. A (Avranches MS 162, 12th century), refers to Uortigerno; and Mommsen's MS. X (Cambridge University Library MS. Ff. I.27) (13th century) calls him Gurthigerno. There is no proof that these names were included in Gildas original text. They may well have been introduced in surviving copies of Gildas at a later date.

The 8th century monk Bede mostly paraphrases Gildas in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People and The Reckoning of Time, adding several details, perhaps most importantly the name of this "proud tyrant", whom he first calls Vertigernus (in his Chronica Maiora) and later Vurtigernus (in his Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum). The Vertigernus form may reflect an earlier Celtic source or a lost version of Gildas, but Bede does not identify his source.

The Historia Brittonum (History of the Britons) was attributed until recently to Nennius, a monk from Bangor, Gwynedd, and was probably compiled during the early 9th century. Nennius wrote more negatively of Vortigern, accusing him of incest (perhaps confusing Vortigern with the Welsh king Vortiporius, accused by Gildas of the same crime).

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle provides dates and locations of four battles fought by the Saxons against the British in the county of Kent. Vortigern is said to have been the commander of the British for only the first battle; the opponents in the next three battles are variously termed "British" and "Welsh", which is not unusual for this part of the Chronicle. The Chronicle locates the Battle of Wippedesfleot as the place where the Saxons landed with hostile intent, dated 465 and thought to be identified with Ebbsfleet near Ramsgate. The annals for the 5th century in the Chronicle were put into their current form during the 9th century, probably during the reign of Alfred the Great. The Chronicle exhibits some bias in favour of the West Saxons.

Putting a date to Vortigern based on the surviving myths is difficult as they are inconsistent. Vortigern is said to marry the daughter of Magnus Maximus while she is still of child-bearing age and Magnus left Britain in c384. St German of Auxerre - came to britain in 429 and apparently met Vortigern. Vortigern would eventually meet his doom at the hands of St German (who died in 448 at the latest). However in 449 Vortigern is inviting the Saxons to Britain and lives long enough to see them revolt in the Treason of the Long Knives.

Later writers such as Geoffrey of Monmouth expand on detail but in Geoffrey's case his primary source appears to be his own imagination. By the date of the documents which survive there had been many opportunities for the content of the original sources to become significantly corrupted.

One theory is that Vortigern might be a royal title, rather than a personal name. The name in Brittonic literally means "Great King" or "Overlord", composed of the elements *wor- "over-, super" and *tigerno- "king, lord, chief, ruler". The "*" means that scholars are not certain about the word. It is indeed unlikely that someone would be baptised with such a convenient name. This point will come up again when considering the names and titles of the "Anglo-Saxons".

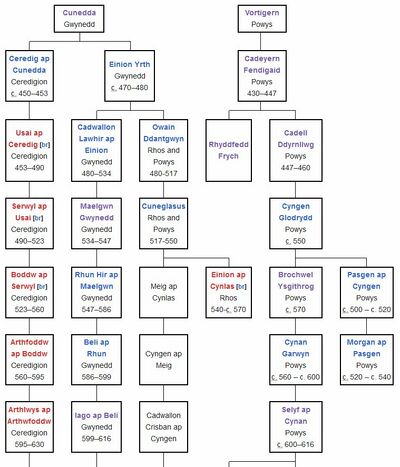

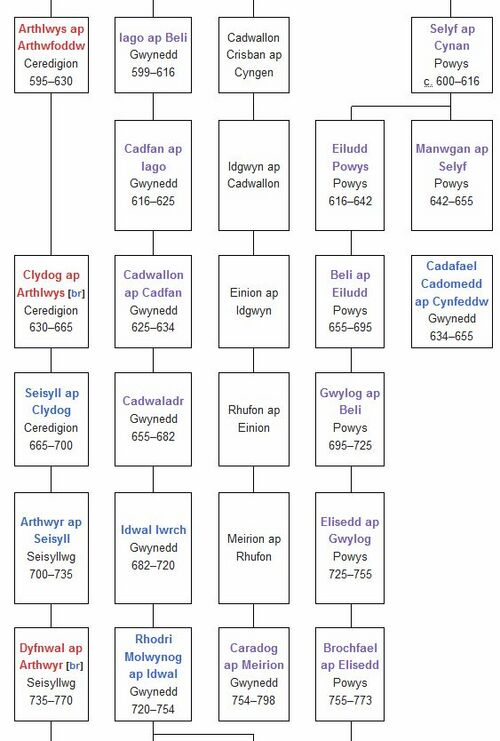

Pedigrees

Vortigern is one of the two "roots" of some of the pedigrees of the Welsh rulers, with the other being Cunedda. These pedigrees need to treated with caution but it is evident that many writers simply take them as historical truth. The main source of early genealogies, the Harley 3859 manuscript, was probably composed under Owain ap Hywel Dda: some other genealogies also appear to date from that time. The existing "copies" date from the 12th century.

Pedigrees that had been in writing for a long time tended to become very lengthy indeed. With each rewriting to add a new generation and grow the pedigree forwards it seems that the pedigree was possibly also extended backwards into the "mists of time". The pedigree of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, the last prince of Gwynedd (d. 1282), for example, as found in the fifteenth-century manuscript (British Library, Harley 673), includes no fewer than ninety-four generations, inclusive of both Llywelyn at one end and Jupiter, Saturn, Noah, Adam and God at the other. Clearly, as a pedigree such as this is traced back there is a point where it becomes suspect.

Fortunately we need not really be concerned with the immediate post-Roman sections of the pedigrees, which are the oldest and more likely to be tampered with (or made up completely in the case of the earliest forefathers). The question of when English was first spoken in Cheshire seems only to be concerned with events after c.600. However there are still issues over rulership in Powys at that time.

Gwynedd and Powys/Pengwern

The Kingdom of Gwynedd was a "Welsh" kingdom and a Roman Empire successor state that emerged in sub-Roman Britain in the 5th century during the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain. The name Gwynedd is believed by some to be a borrowing from early Irish (reflective of supposed Irish settlement in the area in antiquity), either cognate with the Old Irish ethnic name Féni, "Irish People", from Primitive Irish *weidh-n- "Forest People"/"Wild People" (from Proto-Indo-European *weydh- "wood, wilderness"), or (alternatively) Old Irish fían "war band", from Proto-Irish *wēnā (from Proto-Indo-European *weyH1- "chase, pursue, suppress"). The 5th-century Cantiorix Inscription found near Festiniog and now in Penmachno church seems to be the earliest record of the name. It is in memory of a man named Cantiorix, and the Latin inscription is:

- "Cantiorix hic iacit/Venedotis cives fuit/consobrinos Magli magistrati": "Cantiorix lies here. He was a citizen of Gwynedd and a cousin of Maglos the magistrate".

The use of terms such as "citizen" and "magistrate" may be cited as evidence that some elements of Romano-British culture and institutions continued in Gwynedd long after the legions had withdrawn and the magistrates were supposedly ejected.

The Kingdom of Powys was another Welsh successor state, petty kingdom and principality that emerged during the Middle Ages following the end of Roman rule in Britain. The kingdom of Powys itself is first mentioned in the Annales Cambriae under the year 808, and although royal genealogies, none composed earlier than the ninth century, take the line of its kings back to around 600. It very roughly covered the top two thirds of the modern county of Powys and part of today's English West Midlands. During the Roman occupation of Britain, this region was organised with the capital most likely at Viroconium Cornoviorum, the fourth-largest Roman city in Britain. Archaeological evidence has shown that, unusually for the post-Roman period, Viroconium Cornoviorum survived as an urban centre well into the 6th century and thus could have been the Powys/Pengwern capital.

One issue is how far into "England" Gwynedd and Powys extended. The heartlands of Gwynedd appear to have been Arfon and Môn i.e. along the Menai straight; with the latter perhaps the most important locale within the greater Gwynedd kingdom. The remaining areas of north-western and north-eastern Wales comprised a multitude of smaller polities such as Meirionnydd, Dunoding, Dogfeiling, Osfeiling, Edeirnion, Eifionydd, Rhos and Rhufoniog. These were generally considered sub-kingdoms of Gwynedd. Individuals who ruled many of these were identified as the sons and grandson of Cunedda, but this may reflect later creation of a link to a notable ancestor, or the speculations of enthusiastic antiquarians. Their names, with that of the eldest son who died in Scotland, are given by a genealogy of mid-tenth century date probably compiled at St David’s c 955. It may also reflect the British practice of splitting land between several sons, something which could produce a large number of small polities, but the former "foundation myth" explanation is more likely. At the simplest level of corroboration Cunedda is not mentioned in any source other than the Historia Brittonum and the genealogies. Thus the lands up to the River Dee and perhaps at some times up to the Gowy were subject to the Gwynedd hegemony. Despite Offa's Dyke being considered the border at some times, Chester appears to have been a British\"Welsh" city when attacked by the West Saxons under Ecgbert in c829 and at the time of the Battle of Chester in c616.

Pengwern was a Brythonic settlement of sub-Roman Britain situated in what is now the English county of Shropshire, It is regarded as possibly being the early seat of the kings of Powys before its establishment at Mathrafal, further west, but the theory that it was an early kingdom (or a sub-kingdom of Powys itself) has also been postulated. Its precise location and extent are uncertain. The exploits of Cynddylan, as imagined around the 9th century, are told in the Old Welsh Canu Heledd (a cycle of poems named after Cynddylan's sister), possibly dating from the 9th century but not recorded until later, and this material situates Cynddylan's seat at Pengwern. These relate to a further cycle of heroic and elegiac poetry concerning early Powys and the Hen Ogledd known as Canu Llywarch Hen.

According to this semi-legendary material, for which there is little confirmation, Cynddylan joined forces with king Penda of Mercia to protect his realm, possibly also for personal reasons, as his brother Gwion had been killed defending during the Battle of Chester. Together they fought against the increasingly powerful Anglian kingdom of Northumbria at the Battle of Maserfield (Oswestry) in c.642. It was here that their mutual enemy, king Oswald, was slain. This seems to have bought a period of peace until Penda's death at the hands of Oswald's brother Oswiu of Northumbria. Oswiu then surprised Cynddylan's palace at Llys Pengwern. Caught completely off guard and without defence, the royal family, including the king, were slaughtered, according to the poetry commemorating the tragedy, with the palace being burned to the ground, presumably destroying any notional records. Princess Heledd was the only survivor and fled to western Powys.

If Pengwern existed it would have blocked Mercian expansion towards the Irish Sea port at Chester. However the problem with arguments based on the presence of Pengwern is that there is no hard evidence of its actual existence. The "legendary" material appears consistent with the little historical material that exists but appears to have been written down between about 1382 and 1410 based on an oral tradition.

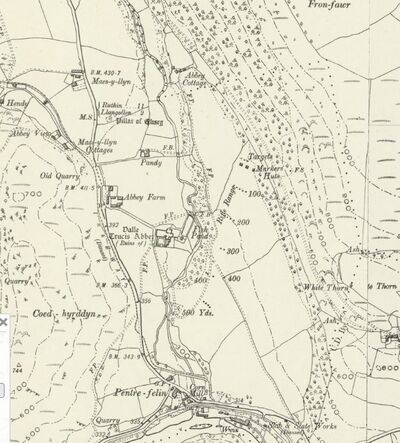

Pillar of Eliseg

The Pillar of Eliseg is located near Valle Crucis Abbey, Denbighshire, Wales [Grid reference SJ 20267 44527]. It was erected by Cyngen ap Cadell (died 855), king of Powys in honour of his great-grandfather Elisedd ap Gwylog (died c. 755). The form "Eliseg" found on the pillar is assumed to be a mistake by the carver of the inscription. Cyngen was the last of the original line of kings of Powys of the Gwertherion dynasty. He had three sons (perhaps four: Gruffudd, Elized, Ioab and Aedan), but on his death Powys was annexed by Rhodri Mawr, ruler of Gwynedd.

A generally accepted translation of the inscription, one of the longest surviving inscriptions from pre-Viking Wales, is as follows:

- † Concenn son of Cattell, Cattell son of Brochmail, Brochmail son of Eliseg, Eliseg son of Guoillauc.

- † And that Concenn, great-grandson of Eliseg, erected this stone for his great-grandfather Eliseg.

- † The same Eliseg, who joined together the inheritance of Powys . . . throughout nine (years?) out of the power of the Angles with his sword and with fire.

- † Whosoever shall read this hand-inscribed stone, let him give a blessing on the soul of Eliseg.

- † This is that Concenn who captured with his hand eleven hundred acres [4.5 km²] which used to belong to his kingdom of Powys . . . and which . . . . . . the mountain

(the column is broken here. One line, possibly more, lost)

- . . . the monarchy . . . Maximus . . . of Britain . . . [Conce]nn, Pascen[t], Mau(n?), An(n)an.

- † Britu son of Vortigern, whom Germanus blessed, and whom Sevira bore to him, daughter of Maximus the king, who killed the king of the Romans.

- † Conmarch painted this writing at the request of king Concenn.

- † The blessing of the Lord be upon Concenn and upon his entire household, and upon the entire region of Powys until the Day of Judgement.

How much of this is history and how much is myth (or propaganda) has been the subject of debate. Those named in the first line can be identified as: Cattell son of Brochmail, Brochmail son of Eliseg and Eliseg son of Guoillauc. Guoillauc, according to traditional Welsh king-lists would be Gwylog ap Beli the great-grandson of Selyf ap Cynan who died in the Battle of Chester.

The names [Conce]nn, Pascen[t], Mau(n?), An(n)an appear on a very badly damaged section of the column. Pascent appears in a genealogical argument which flared up in the 9th century around the dynasties that claimed the legitimacy of the throne of Powys. These were the dynasties of Cadell Ddyrnllwg (promoted by the Historia Brittonum) and of Catigern ((Welsh: Cadeyrn Fendigaid) said to be confirmed by the Pillar of Elise), which claimed descent from Vortigern. The Historia Brittonium says of the sons of Vortigern:

- "He had three sons: the eldest was Vortimer, who, as we have seen, fought four times against the Saxons, and put them to flight; the second Categirn, who was slain in the same battle with Horsa; the third was Pascent, who reigned in the two provinces Builth and Guorthegirnaim, after the death of his father. These were granted him by Ambrosius, who was the great king among the kings of Britain. The fourth was Faustus, born of an incestuous marriage with his daughter, who was brought up and educated by St. Germanus."

Brittu is named as the son of Vortigern by Sevira, daughter of Magnus Maximus. The connection between Vortigern and Brittu is is mentioned in no other source. The Pillar of Eliseg inscription is also the only known source for a daughter of Magnus named Sevira (or Severa). In the "Matter of Britain" Vortigern also marries Rowena, daughter of the purported Anglo-Saxon chief Hengist: she is first recorded by name in the work of Geoffrey of Monmouth (so it is possible he made the name up). Geoffrey claims the drunken seduction of Vortigern created the tradition of toasting in Britain. According to the Historia Brittonum, Vortigern "and his wives" (Rowena/Rhonwen is not named directly) were burned alive by "heavenly fire" (brought down by Germanus) in the fortress of Craig Gwrtheyrn ("Vortigern's Rock") in south Wales.

Comparing the list of names on the pillar with those in the traditional Welsh king-lists it is possible to hazard a guess when the part of Powys referred to was lost. The inference is that Elisedd ap Gwylog was not the one who lost this part of Powys, so the loss may have occurred during the reign of Beli ab Eiludd (655-695?) or Gwylog ap Beli (695?–725).

So why was the pillar errected? It could simply be a monument to an ancestor with no sub-text in the context. It could be a rallying call to Powys to repeat the deeds of their noble ancestors going back to the Romans and recover their rightful land from the Mercians. It could be that Cyngen ap Cadell was already well aware that Gwynedd had Powys in its sights for a take-over and wanted to emphasise that he and his sons were the rightful heirs.

Summary so far

Chester makes much of its Roman past but digging into the detail reveals a spread of "jigsaw pieces" that could indicate a quite different post-Roman evolution to that in the south and west of Britain from which most "popular" theories about the advent of the Saxons have arisen.

It is not entirely clear when "Roman Britain" ended in Cheshire. With the withdrawl of Legio XX possibly around 383 this could be earlier, in effect, than in the south of England, where a date of 411 is frequently used. There is an argument for surviving Roman culture at Viroconium (Wroxeter) which would have delayed the migration of Anglo-Saxons towards Cheshire. There is also an argument for surviving Roman culture in north Wales, but this is not supported by archaological evidence, and the theory of its survival is much influenced by Welsh legendary material written down many years later. These include "foundation myths" for Gwynedd and Powys of which there appear to be several early variants. For example, the Pillar of Eliseg (built before 855) traces a pedigree for Powys that runs back to Magnus Maximus and Vortigern.

At the time of the Battle of Chester, some 200 years after the "end of Roman Chester", the Saxons do not seem to have settled what is now Cheshire, much of which was possibly part of Powys. Such was the delay between the advent of the Saxons c.450 and their probable arrival in Cheshire perhaps 200 years later that little of any "survival" of Romanitas, with the possible exception of Wroxeter would have had any impact on the language spoken in Cheshire.

Written Evidence

Some care and caution is needed with the written evidence, especially that which was only generated after years of oral transmission or that which may have been compiled or copied with changes for "political" reasons. It is important to distinguish between what can be reasonably assumed to be accurrate and what is effectively story-telling. The writing of Saint Patrick and Gildas apparently demonstrates the survival in Britain of Latin literacy and Roman education, learning and law within elite society and Christianity, throughout the bulk of the fifth and sixth centuries. Some see signs in Gildas' works which indicate that the economy was thriving without Roman taxation, as he complains of luxuria and self-indulgence. Of course Gildas may only be writing a polemic against a small elite. In the mid-fifth century, "Anglo-Saxons" begin to appear in an apparently still functionally Romanised Britain, so a key factor in analysis of the period is how quickly and when the culture changed due to outside influences. It is also worth noting that the lables "Angles" and "Saxons" raise some issues as to exactly what early authors meant by them.

Early Evidence

The first set of written evidence is that which comes from late Roman writers in the period before 450, at least some of whom may have been alive during the time of the first Saxon raids on late and post Roman Britain.

Ammianus Marcellinus

Ammianus Marcellinus (330 - c391 – 400): his account of the "British War" of 343 has been lost but he refers to it in extant works. According to his account, the Picts, Attacotti and Irish were raiding widely, while the Franks and Saxons were plundering parts of Gaul at some time between 343 and 367. Ammianus was living in Antioch at the time he wrote, but he is the source for the "Great Conspiracy", a year-long state of war and disorder that occurred near the end of Roman Britain. In the winter of 367, the Roman garrison on Hadrian's Wall rebelled and allowed Picts from Caledonia to enter Britannia. Simultaneously, Attacotti, the Scotti from Hibernia and (according to some interpretations) Saxons from Germania landed in what might have been coordinated and pre-arranged waves on the island's mid-western and southeastern borders, respectively.

The warbands managed to overwhelm nearly all of the loyal Roman outposts and settlements. The entire western and northern areas of Britannia were overwhelmed; the cities sacked; and the civilian Romano-British murdered, raped, or enslaved. In the spring of 368, a relief force, commanded by Flavius Theodosius, gathered at Bononia (Boulogne-sur-Mer). It included four units, Batavi, Heruli, Iovii and Victores, as well as his son, the later Emperor Theodosius I, and probably the later usurper Magnus Maximus, his nephew. Considerable reorganization was undertaken in Britain, including the creation of a new province, Valentia, probably to better address the state of the far north.

It is possible that Theodosius mounted punitive expeditions against the barbarians and imposed terms upon them. Certainly, the Notitia Dignitatum later records four units of Attacotti serving Rome on the Continent. What happened next only survives as a mix of myth and legend, although many writers will continue at this point without noting that what follows is speculation.

The areani (native British troops) were removed from duty and the frontiers refortified with co-operation from other border tribes such as the Votadini, which marked the career of men such as Paternus (Padarn Beisrudd). One traditional interpretation identifies Paternus as a Roman (or Romano-British) official of reasonably high rank who was placed in command of the Votadini troops stationed in Clackmannanshire in the 380s or earlier by Roman Emperor Magnus Maximus. Alternatively, he may have been a frontier chieftain in the same region who was granted Roman military rank, a practice attested elsewhere along the empire's borders at the time. His command in part of what is now Scotland probably lasted until his death and was then assumed by his son Edern (Edeyrn=Eternus). Edern is traditionally considered to be the father of Cunedda, traditional founder of the Kingdom of Gwynedd. Dates for the arrival of Cunedda in Wales range from the 370's (under Magnus Maximus) to the late 440's.

This provides two links to the Irish Sea region and in particular to north Wales. The earliest Welsh genealogies give Maximus (referred to as Macsen Wledig, or Emperor Maximus) the role of founding father of the dynasties of several medieval Welsh kingdoms, including those of Powys and Gwent. He is given as the ancestor of a Welsh king on the Pillar of Eliseg, erected nearly 500 years after he left Britain. For more on Maximus see below and the article on Elen of the Hosts.

Claudian