Gowy

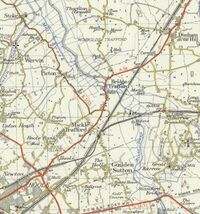

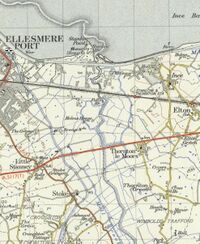

The Rivers Gowy and Weaver rise in almost the same field at Peckforton. The head of the Gowy is about sixteen miles from where it empties into the Mersey estuary "as the crow flies", but the wandering of the river adds at least nine more miles to that. It used to wander even more before many of its meanderings were straighened out - mostly by Italian POW's in WW2 (there were POW camps at Knutsford and Crewe Hall). Surprisingly, this short and often insignificant looking river and its branches have been made to work incredibly hard, they powered around twenty or more water-mills. The Gowy flows entirely within Cheshire.

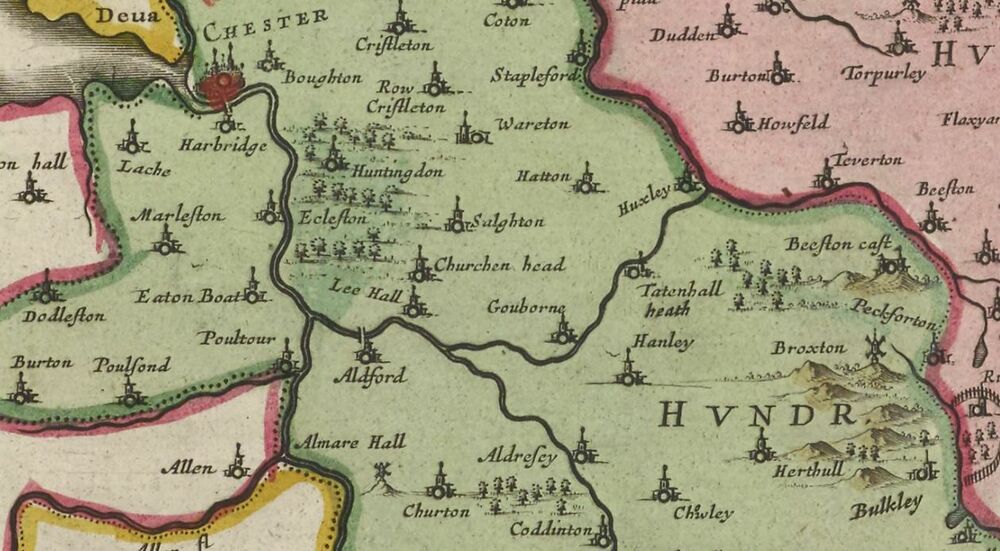

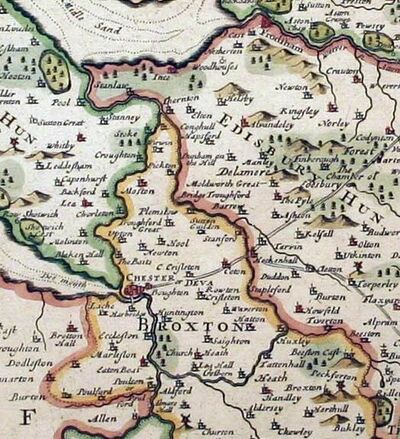

Early maps and descriptions give a seemingly improbable course for the Gowy, with the river splitting in two at least twice and branches emptying into the River Dee via Aldford Brook and Backford Gap. Ormerod cites a very peculiar version of the course of the Gowy, with it actually dividing the Wirral from the rest of Cheshire by flowing into both the Dee (as Flookersbrook) and the Mersey:

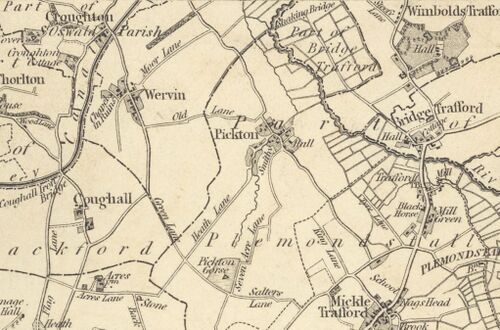

- "That, therefore, which they call the Gowy, hath his head not far from Bunbury, and runneth north-west by Beeston Castle, to Teerton and Huxley, where it divideth itself into two parts ; one goeth west to Tattenhall, Gosburn, Lea Hall, and at Aldford falleth into the Dee. The other part goeth northwards to Stapleford, Hocknel-plat, and Barrow (where it taketh in a brook that Cometh from Tarporley and Tarvin), and so passeth to Plemstow-bridge, Trafford, Picton, and Thornton, where it divideth itself again into two parts; one of which keepeth its course north-west to Stanley, Stanney, and Poole, and afterwards falleth into the Marsey. The other part goeth south-west to Stoke, Croughton, Chorlton, the Baits, and so falleth into the Dee, hard by Chester, being there called Flooker's-brook, and divideth Wirral from the rest of Cheshire; and therefore some imagine that it is called Wirral."

This supposed course of the river is used to define parts of the bounary of the Broxton Hundred. However, it may well be that significant parts of the river were diverted at various times and in various places, particularly to power water-mills, or to prevent or reduce flooding. Even today, the boundaries are often the old ones and do not always follow the mid-line of the river. However diversion of the river was never on the scale that Ormerod implies. Why Ormerod should get it so wrong is a mystery, as he lived at nearby Chorlton Hall in Backford while writing his "History of Cheshire" and should have been familar with the local hydrology. One possible theory (little more than speculation) is that the Gowy had a reputation for flooding and this linked it in a very loose sense to other minor local rivers which were prone to flood, such as what later became "Finchett's Gutter" (hence "Stone Bridge" - see Flookersbrook) and Golborne Brook (see Civil War) which may have been the site of the dawn ambush which started the Battle of Rowton Moor.

Geology

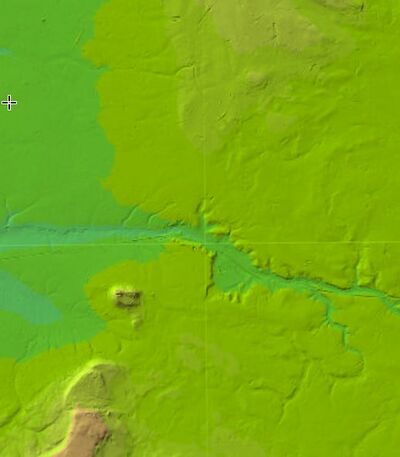

The Gowy flows over a thick layer of glacial and coastal deposits which overlay several related types of sandstone. One of these sandstone formations, the Sherwood Sandstone, is the UK’s second most important aquifer. Near the coast there are peat beds. Nowhere does the Gowy flow over rock or fall steeply enough to produce a natural waterfall or rapids. Its porous bed means that water is frequently exchanged with the surrounding ground. Near the sea, there are deeply incised buried drainage channels, probably dating from the ice ages, which are filled with gravel and invisible on the surface. These undoubtedly influence groundwater flow but have a very complex form which has not been accurately mapped, although the important groundwater resources along the Gowy have been studied in some detail. The drift cover has the effect of smoothing the topographic surface of the pre-glacial landforms. Drift cover in the Gowy Valley is at a depth of 30 metres below sea level. Drift cover is of substantial thickness in places, for example it exceeds 30 metres thickness in the NNW-SSE trending steep-sided valleys along the River Gowy between Helsby and Tarvin.

Beneath the sandstones are the Pennine Coal Measures Group and Millstone Grit Formations and underlying these are the shales and limestones of the "Craven Group", which have been a target for shale gas exploration ("fracking"). These Carboniferous rocks date from the geological period prior to the desert conditions in which the Cheshire sandstones were formed. The gross geology of the Cheshire plain is that of a "graben" where later sandstone survives between the older rocks of the Wrexham and Macclesfield coal-measures to the east and west. Coal measures exist beneath the Cheshire plain, but are too deep to mine. Ince is an exception in that the deep-buried coal measures (normally 1.5 km down) are faulted upwards to form a "horst" (but still at 0.94 km down, too deep for practical mining, especially given the hydrology). This horst is bordered by the Waverton fault zone to the west, and the Dungeon Banks fault zone to the east. The only surface indication of this immense underground feature may be the slight rise at the mouth of the Gowy.

The topological character of the river's course can conveniently by divided into four sub-regions:

- The early reaches of the river drain uplands at about 300 feet of altitude. These upland areas are largely drained by the River Weaver and so the volume of the Gowy is quite modest and it is seldom more than a few feet wide during normal weather conditions. It takes a wandering course to reach the level of the canal and railway at about 150 feet.

- The river then passes through a gap in the sandstone ridge running down the center of the Cheshire plain. The gap is probably the result of glacial activity and meltwater flow. While the Gowy may have contributed to the final detail of the valley it did not itself carve out the bulk of it.

- The Gowy emerges from the gap about 100 feet above sea level, onto lowland pasture between Huxley and Stamford Bridge. The land is flat enough to require some drainage ditches but not a excessive number. The land is extensively cleared and there is only a little surviving woodland, some of which may have been left as cover for the foxes that the gentry loved to hunt. The most obvious features in the Cheshire landscape, as seen from the air, are the fields. Some of them are rectangular, very regular and plainly recent. Others are less regular and are presumably older. A few fields are markedly oval and were either assarts formed at the edges of extensive woodland or, as is more likely, they are the sites of small woods or copses that have been destroyed to provide extra pasture or land for crops. Marl pits are frequent. Secondary calcium carbonate deposits are common at a depth of 1-2m in the till, and before cheap lime was made available in the 19th century this "marl" was dug and spread on the surrounding fields to reduce acidity. On sandy soils this practice of marling also increases fertility and moisture holding capacity.

- Below the Roman crossing at Stamford bridge, the Gowy makes its way to the sea in across a broad coastal plain which was once subjected to tidal inundation and is still intersected by many drainage ditches. This land was probably marginal until the construction of the Manchester Ship Canal and the railways reduced the risk of tidal flooding, although the tithe maps indicate that much of the ditching was in place by the 1830's. The slopes of the valley sides provide somewhat drier ground as a pastoral fringe. In relatively recent times this area would have been influenced by changes in sea-level. Relatively recent changes to sea-level, include a period of transgression in Roman times that peaked in the late fourth century, when previously unaffected areas would have been subject to inundation. Sea level fell to close to present levels by the seventh century, rising again until the late thirteenth century, from which it has fallen to present levels.

It has long been the contention of historians that the county's lands had largely been enclosed by the 17th century, and it is interesting that the scattered farmhouses of west Cheshire, many of which are of 17th-century date, tend to confirm this. Those of them that are of timber-frame construction frequently contain re-used structural timbers, implying the existence of even earlier buildings at the same locations or nearby. It is a common myth that any odd-looking timber used in an old building is re-used "ship timber". That is simply untrue. Once forests had been cleared, wood became a valuable commodity and when enclosures gathered scattered land-holdings in close-knit groups any farm-house that was built would use recycled materials from earlier constructions. Enclosure was delayed by some land-owners and in Cheshire the subject is a complex one. Enclosure has may other effects than simply producing hedgerows (which are not as old as some might think) and are of course an entirely man-made aspect of the landscape. Footpaths and rights of way were established, as were many country roads. The Christleton Enclosure award created several new roads from Christleton to Cotton and Hockenhull Platts, to Waverton and across Birch Heath and Stamford Heath to the Chester-Tarvin turnpike. At Bunbury, allotments were set-up for small-scale vegetable farming.

Mineral resources along the river are mostly limited to a few sand and gravel pits, although copper was found just south of its source. One consequence of the copper find has been the inspiration for a model of the fictional Peckforton Light Railway (not located at Peckforton). The general boggyness of the rivers banks and a tendency to flood in parts of its shallow valley has meant that no major settlement has developed along its banks and hamlets or small villages such as there are tend to be located on drier ground set back at some distance from the River. There is farming land along almost all of the river, with little forest remaining. Agriculture is now dominated by pasture, but the presence of the mills indicate that corn was grown, as does the fact that the arms of Cheshire feature sheaves. Apart from where it passes through the gap in the Sandstone Ridge, a gap defended by the castle at Beeston, the valley of the river is little used for commerce along its length. The natural processes of vegetation succession have reduced many marl-pits to small, shallow features, over-shaded with trees and with little open water. Nevertheless, it is estimated that Cheshire’s 16,000 ponds represent some 10% of all farm ponds in England and Wales, and still provide an important wildlife resource.

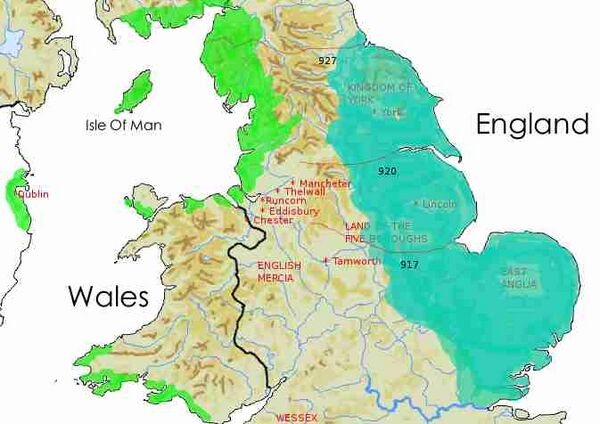

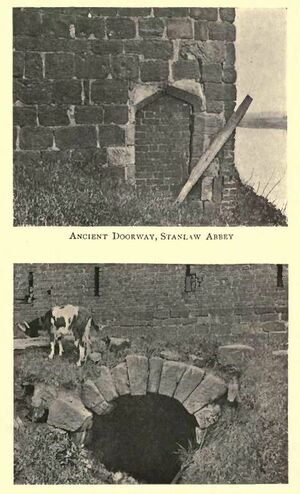

Some have suggested that the river may once have formed a natural border between England and Wales, and note that in earlier times, this river was possibly called the Tarvin. It is suggested that the name Tarvin comes from the Brittonic word for boundary, which is still present in the Welsh language as tervyn/terfyn and could have resulted from the Latin terminus being incorporated into Brittonic. The boundary could refer to the eastern extent of the Roman "prata legionis", the land annexed by the Romans (from the Cornovii) to support their fortress at Chester. The Gowy was later the boundary between the Saxon land divisions (hundreds) in this area, in particular forming the western boundary of the Eddisbury Hundred. The Gowy may well have been an important boundary from a very early age and one for which the "permiability" varied with changes in sea-level as discussed above. There is some evidence that there were cultural differences accros this boundary from the "stone age": the stone axes discovered in the Wirral and western Cheshire are mostly from North Wales, whereas those found in the Mersey and Weaver valleys come from Cumbria.

The Source

<== CLICK ON THE WALKING MAN TO GET MAPS, LIDAR ETC.

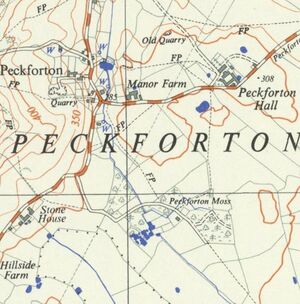

The official source of the Gowy is near grid-reference SJ539563 (see the 1909 OS map). From Peckforton Moss the stream flows northwards through the hamlet of Peckforton, where the first mill down from the source of the river Gowy was located, as shown on the 1909 OS map. Only scant signs of the millpond remain, but surprisingly the remains of the mill can be stumbled upon. Even the millstones have been located due to the work of landscape geographer David Keogh. Inscriptions on some of the surviving stonework appears to give a date of 1698, although it is unclear whether that is meant as a date of building or later graffiti. In corn mills rotation about a vertical axis was required to drive its stones. The horizontal axis rotation of the wheel was converted into the vertical rotation by means of gearing, which also enabled the runner stones to turn faster than the waterwheel. The usual arrangement has been for the waterwheel to turn a horizontal shaft on which is also mounted a large "pit wheel". This meshes with the "wallower", mounted on a vertical shaft, which turns the (larger) "great spur wheel" (mounted on the same shaft). This large face wheel, set with pegs, in turn, turned a smaller wheel (such as a lantern gear) known as a "stone nut", which was attached to the shaft that drove the runner stone. The number of runner stones that could be turned depended directly upon the supply of water available. As waterwheel technology improved mills became more efficient, and by the 19th century, it was common for the great spur wheel to drive several stone nuts, so that a single water wheel could drive as many as four stones.

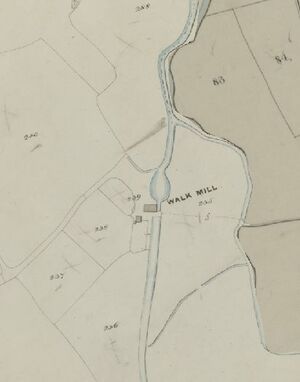

The development of the water-mill was an important technology milestone. It superceeded the use of manual threshing which was a laborious process. From the late 10th century onwards, there was an expansion of grist-milling in Northern Europe. In England, the Domesday survey of 1086 gives a precise count of England's water-powered flour mills: there were 5,624, or about one for every 300 inhabitants: often quoted as one for every thirty households. Windmills only appeared in England from about 1180. The invention of mechanical fulling by waterpower was apparently introduced to these islands by religious orders, particularly the Cistercians. Fulling mills for wool turned England into a major cloth-making country from the 14th century. They were known as "walk mills" in northern England and "tuck mills" in the South-west.

The river has only fallen a few feet to reach this point and so the fact that it has the strength to power a mill is remarkable. However it would be wrong to assume that this was a flour mill. Many of the mills along the Gowy may have produced animal feed, which does not need to be as finely ground. Feed was needed as the farming practice in Cheshire was to move the animals indoors for the winter months amd tillage was often limited by landlords to increase the dairy output. The river already has less than 300 feet to fall before it reaches the tidal waters of the Mersey. In 1901 a local farmer found a neolithic stone hammer near here. The hammer was made of Cumberland granite and must have been either traded 5-6k years ago or made locally from a glacial "erratic".

Peckforton appears in the Domesday survey of 1086, when it was held by Wulfric (possibly Wulfric Spot). The survey lists land for two ploughs. Peckforton fell in the ancient parish of Bunbury in the Eddisbury Hundred.

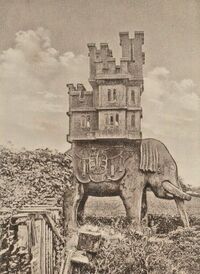

Near the head of the river Gowy, a red sandstone carving depicting an elephant bearing a castle as a howdah stands in the garden of Laundry Cottage on Stone House Lane in Peckforton village. It dates from around 1859 and is listed at grade II. It was carved by John or William Watson, a local stonemason then working on Peckforton Castle who also carved stone lions now at Spurstow and Tattenhall. The elephant and the castle are each carved from a single piece of stone, which derives from the same quarry as Peckforton Castle. The elephant has a tasselled saddle, supporting the castle which has three tiers, with a turreted gatehouse and a keep with turrets at the corner. Some of the castle windows are glazed. The original purpose of the carving is unclear. The device formed part of the crest of the Worshipful Company of Cutlers and is often associated with public houses, but there has never been a pub called The Elephant and the Castle in Peckforton. An elephant also appears in the arms of the Corbett family, local landowners before 1626. The "canting" arms of the Corbets is usually a raven (from "corvus"), but the "crest" on the top of the shield is an elephant and castle. There are links between the Corbets and the Cottons of Combermere Abbey - Stapleton Cotton, 1st Viscount Combermere (14 November 1773 – 21 February 1865) extensively modified Combermere, saw military service in India, and was appointed a Knight of the Order of the Star of India on 19 August 1861. Maybe the elephant was intended for Cotton - the elephant and castle is actually used as a heraldic motif at Combermere and Cotton once famously confronted a tiger while hunting on an elephant. According to one local source, the carving was originally intended as a beehive, although there is no evidence it has ever been used as one (curiously the "canting" arms of the Beestons, as featured at Bunbury Church, has bees). The elephant is one of several listed structures in Peckforton.

Peckforton Castle was built between 1844 and 1850 for John Tollemache, the largest landowner in Cheshire at the time, owning 28,651 acres (115.95 km2). His estate exceeded those of the Duke of Westminster who owned 15,138 acres (61.26 km2), Lord Crewe with 10,148 acres (41.07 km2) and Lord Cholmondeley with 16,992 acres (68.76 km2). He was described by William Ewart Gladstone as "the greatest estate manager of his day". Tollemache's first choice of architect was George Latham of Nantwich, but he was not appointed, and was paid £2,000 in compensation. Instead Tollemache appointed Anthony Salvin, who had a greater reputation and more experience, and who had already carried out work on the Tollemache manor house, Helmingham Hall in Suffolk. The castle was built by Dean and Son of Leftwich, with Joseph Cookson of Tarporley acting as clerk of works. Stone was obtained from a quarry about 1 mile (2 km) to the west of the site, and a railway was built to carry the stone. The castle cost £60,000.

Even at it's very source the waters of the river Gowy are robbed away by man. The headwaters actually seep down from Bulkeley Hill, where the remains of a tramway used in the construction of the Bulkeley Hill reservoir and water main, including a massive anti-surge valve at the top of the tramway can still be seen. There are foundations for a haulage angine at the top of the line, and a crossing point half-way. The climb up the track is approximately 105 metres of ascent. The tramway is on the route of the water-main supplying the water to the Potteries. This is actually a far more modern structure than might be thought. It was only in 1937 that the Staffordshire Potteries Water Board gained authority for the erection of pumping stations at Peckforton and Tower Wood in Cheshire, with a reservoir on Bulkeley Hill, whence the water would gravitate to a large storage reservoir at Cooper’s Green near Audley, for distribution to Tunstall and the Potteries. Most of these enterprises were held up by the Second World War and it wasn't until 1953 that the Peckforton scheme and its linking aqueduct to Audley had been completed. There are two boreholes where water is pumped from the Sherwood Sandstone aquifer which is near to the surface: Close to the Coppermine Inn (three pumping stations) and at Peckforton Gap. There is a holding reservoir at the Gap, from where water is pumped up 110 metres to a covered reservoir on Bulkeley Hill at 210 metres above sea level. From there a 27 inch steel pipe feeds the water under gravity to the reservoir at Cooper’s Green, Audley, 140 metres above sea level. While the sandstone under the Cheshire plain contains a vast aquifier the level has been affected to the point where the deep well at Beeston Castle is now dry and the springs and seepages which feed the Gowy are no-doubt much diminished. The canal takes no water from the Gowy and at times even overflows into it. Instead the canal is fed from the River Dee to the Hurleston Reservoir, which is filled by water which passes along the canal from the Horseshoe Falls at Llantysilio. As well as supplying the canal, the reservoir is used for drinking water, holding 85 million gallons (390 Ml). Around 12 million gallons (55 Ml) flow along the canal each day to supply it. The use of the canal as a water feeder ensured that it survived, including the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct, when other canals fell into disrepair.

These upper sections of the river Gowy appear to have either been shifted in their course several times or some of the early mapping is innaccurate, and drainage ditches may have been mistaken for the course of the river. In places the river even appears to dissappear beneath the ground. Some modern maps even label the river Gowy as the stream which flows from Spurstow Hall, through Woodworth Green, towards the canal at Calveley and only joins the true Gowy at Tilstone. As the Gowy makes its relatively short journey to the sea, or rather the Mersey estuary the influence of man becomes more marked. It's valley is used for a canal and railway, mills have been built at almost every opportune location and often it's course has been shifted by their leats. Further downstream its waters were divided for mills to such an extent that the main course was at times very diminished. The river's mouth now lies in the midst of a vast petrochemical complex and there have been long arguments as to whether "fracking" should be allowed in its lower valley.

Tithe maps

Tithes were originally a tax which required one tenth of all agricultural produce to be paid annually to support the local church and clergy. Parishes were created across England in the 11th and 12th centuries, with their associated parish churches. A major impetus to this development was the legal exaction of agricultural tithes specific to the support of churches and their clergy; landowners needed to establish parish churches on their lands in order to retain tithe income within their estates, and to this purpose sought to raise former field churches to parish church status. This was generally performed by a lord of a manor by rebuilding a church within the boundary of his manor, or within that of a newly subinfeudated (sub-let) manor, and then transferring proprietary rights of certain individual named fields, mills or messuages (i.e. houses on the manor which earned rents) to establish a "glebe". The lord of the manor, having incurred a great expense in building the church and parsonage and having suffered a loss of income due to his donation of property to the glebe, quite reasonably insisted on the right to select the individual who would act as the parson (parish priest), from which office he could not be ejected by the lord until the priest's death. This right became the "advowson" - a right to present a canditdate. After the Reformation much land passed from the Church to lay owners who inherited entitlement to receive tithes, along with the land. Depending on how the tithes were apportioned, a parson may be a rector (received direct payment of both the greater and lesser tithes of his parish) or a vicar (received only the lesser tithes with the greater tithes going to the lay holder). A parish priest who received no tithes (where the land-owner kept the lot) was legally a perpetual curate (to distinguish him from assistant curates). The title of perpetual curate was abolished in 1968.

By the early 19th century tithe payment in kind seemed a very out-of-date practice, while payment of tithes per se became unpopular, against a background of industrialisation, religious dissent and agricultural depression. The 1836 Tithe Commutation Act required tithes in kind to be converted to more convenient monetary payments called tithe rentcharge. The Tithe Survey was established to find out which areas were subject to tithes, who owned them, how much was payable and to whom. Enquiries were directed to every parish or township listed in the census returns. The results of these enquiries are in the tithe files, which cover the whole of England and Wales, and not only those places where tithes remained uncommuted by 1836. For parishes where tithes were still being paid in kind, the land had to be surveyed and valued, to arrive at total parish rentcharge figures, and to calculate each individual landowner’s liability to pay tithe. Assistant tithe commissioners travelled to these parishes to hold meetings with parishioners about valuations, and to settle the terms of the commutation of their tithes.

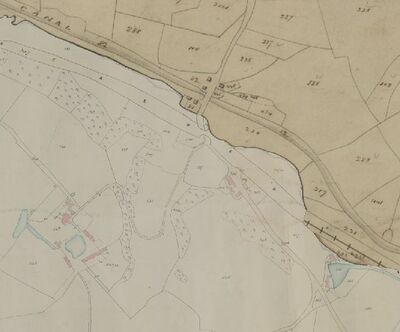

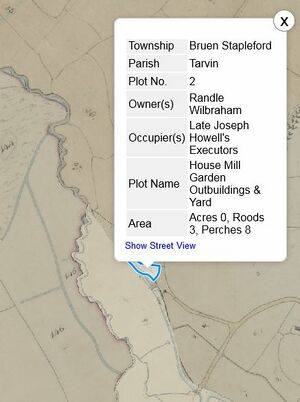

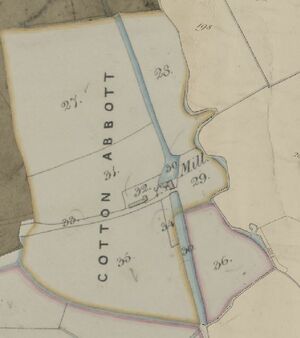

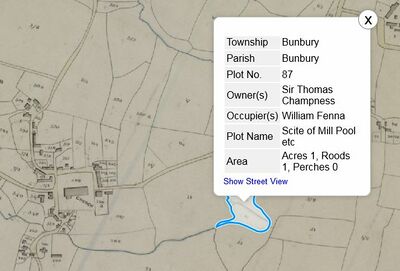

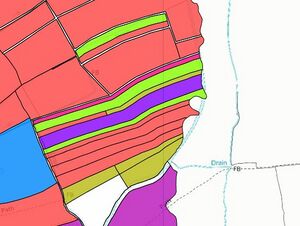

One result of the Tithe Commutation Act was the production of "Tithe Maps". These show the ownersship, occupation and often the use of land at the time, and provide useful details such as field names. They enable properties such as water-mills and smithys to be identified. The agreed terms were formalized in a document called a tithe agreement, if all parties concurred, or a tithe award, if the assistant commissioner had to arbitrate in a dispute. The agreement or award formed the basis of the tithe apportionment, which was the legal document setting out landowners’ individual liabilities. Each apportionment was accompanied by a map; both were signed by the Tithe Commissioners. Tithe rentcharge then became payable. Cheshire Archives and Local Studies has made the county Tithe Maps available online at no charge. These maps show much of the life along the Gowy that has almost become lost in modern times.

Peckforton

- "PECKFORTON, a township, in the parish of Bunbury, union of Nantwich, First division of the hundred of Eddisbury, S. division of the county of Chester, 4½ miles (S. S. W.) from Tarporley; containing 309 inhabitants. It comprises 1741 acres, of which the soil is half clay, half sand. Horseley Bath, a mineral spring formerly in considerable esteem, is in the township" - A Topographical Dictionary of England. Originally published by S Lewis, London, 1848.

Roughly opposite the marshy remains of Peckforton Mere and the now drained ground which was Ridley Pool was a cottage provided with stone faces. This has been a source of some confusion. This is not the noted "image house", although it has been confused with it in some guidebooks. Coward mentions the confusion in his "Cheshire Traditions and History". The "real" image house is a little way further down the Gowy between Beeston hamlet and Bunbury.

Tollemache

Members of the Tollemache family (pronounced "TOL-mash") had a significant impact on the economy and politics of East Anglia since the reign of Edward I and are believed to have been living in Suffolk since before the Norman conquest.

The Cheshire branch of the family arose through intermariage. The Tollemache family married into the Wilbraham family. The Wilbrahams of Woodhey traced their ancestry back to Sir Richard de Wylburghham, Lord of Wymincham and Radnor in right of his second wife. He died about 1273. His second wife was Letice, eldest daughter and coheiress of William de Venables of Wymincham and Radenore, younger son of Sir William Venables, baron of Kinderton. Woodhey was obtained about 1416 by the marriage to Thomas de Wilberham of Radnor to Margaret the daughter and heiress of John de Golborne. After Sir Thomas’s death in 1692 the Wilbraham baronetcy became extinct. There being no male heirs, the Woodhey estate passed by marriage to Lionel Tollemache, Lord Huntingtower, who had married Thomas Wilbraham’s second daughter, Grace, in 1680. Lionel Tollemache was the eldest son of Elizabeth Dysart, the formidable chatelaine of Ham House, Surrey. Accused of witchcraft by her enemies because of her political influence, Elizabeth was also rumoured to have poisoned her husband. Tollemache certainly appears to have been plagued with ill-health throughout much of his life. Augustus Hare, in The Story of My Life (1900) suggested that this was as a result of his being slowly poisoned by his wife, who had used up his fortune turning Ham House into a grand palace and now needed new sources of income with which to pay off her creditors. There is no evidence to back up such a claim however and it must be seen that Elizabeth's reputation has suffered from its subsequent association with that of her second husband, John Maitland, 1st Duke of Lauderdale, whom it was said she charmed even as her husband 's health deteriorated. Tollemache travelled to France in search of cures for his debilitating sickness, but died in Paris.

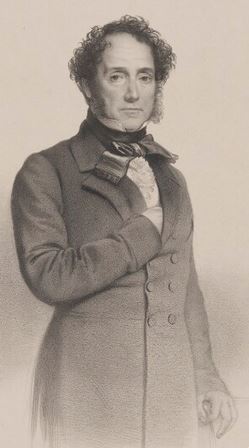

Activity in Cheshire was put on a firm footing by Admiral John Richard Delap Halliday. He was the son of Major John Halliday (died 1794) who owned plantations in Antigua and St Christopher. These plantations were established by the Scots ancestors of the Hallidays. John Halliday was the owner of sugar plantations and married Elizabeth Delap whose family had been early settlers in Antigua. Admiral John assumed the additional name of Tollemache after succeeding to the Peckforton, Helmingham and various Cheshire estates in 1821 upon the death of Wilbraham Tollemache, the brother of his mother Jane. After Admiral Halliday had in this way become Admiral Tollemache he stood for parliament as a Radical — the constituency he chose was in Cheshire. It has been suggested that his reason was probably his love for the excitement of an electrion and, not least, to rouse the ire of what he described as his "squirearchical neighbours".

John Halliday fought one naval action which has become celebrated. This was in 1810 when he was in command of H.M.S. Repulse, a 74 gun ship taking part in the blockade of the port of Toulon. On 31 August in that year Repulse's lookout reported that several French ships were in sight; these were in pursuit of 18-gun Cruizer-class brig-sloop H.M.S. Philomel. The French fleet comprised 8 ships of the line and a covering force of 4 frigates. At first it looked certain that the flying Philomel would be taken or perhaps de-stroyed, the supporting British fleet being out of touch and unable to intervene. Without a moment's hesitation Repulse made sail and placed herself between the French and their intended victim. As soon as he was in range of shot John opened fire on the leaders of the chase. His immediate and spirited action, as well as his accurate broadsides, quickly discouraged the French frigates in the van — the Penelope, Pomme and Adrienne — and they broke off the contest. The whole French fleet, cheated of what had looked to be a certain victory, then withdrew to Toulon. Once the outcome was clear, H.M.S. Philomel made a signal — "Well done Repulse. Repulsed the enemy. Saved me nobly."

His son John Tollemache built Peckforton. Tollemache served as High Sheriff of Cheshire for 1840 and was then elected to the House of Commons as MP for Cheshire South from 1841 to 1868, and Cheshire West from 1868 to 1872. He believed in a self-reliant labouring class and made popular the idea of his tenants having a cottage with sufficient land to keep a few animals. His catch-phrase for this was "three acres and a cow", although the saying has been attributed to others. He built around fifty-five farmhouses at a cost £148,000 and spent a similar amount on cottages. Portrayed by his son as an eccentric despot, Tollemache’s widely admired benevolent paternalism was evidently coloured by a highly authoritarian regime at home, where he is said to have fathered at least 25 children. His many foibles included the burning of clothes left lying around his hallways and the wearing of a wig, despite having a full head of hair.

Tollemache is often associated with slavery: he had received £12,667 as compensation for the freedom of 822 slaves on Antigua in 1839. Part of this funded Peckforton but much went to the holders of a debt secured on the estate. His father, Vice Admiral John Richard Delap Tollemache, had himself built Tilstone Lodge, around 1832. The Vice Admiral had taken his mother’s name, and the family represented the union between slave wealth from the Delap Halliday family of Antigua and the landed English wealth of the Tollemaches.

John Tollemache passed away in 1890 at the ripe old age of 85. Only 12 of his sons survived him. He was succeeded by Wilbraham Tollemache. He was elected to the House of Commons for Cheshire West in 1868 (succeeding his father), a constituency he represented until 1885. In 1890 he succeeded his father as second Baron Tollemache and took his seat in the House of Lords. The last member of the Tollemache family to live in the castle was Lord Bentley; who left Peckforton in 1939 and took up residence in Eastbourne. During World War II, in Lord Bentley’s absence the Castle provided care and a safe home to disabled evacuee children. Over the years, Lord Bentley was the author of several books on croquet and on contract bridge.

The Storm

By Stone House Lane stands the ancient Peckforton Oak on its grassy knoll. Known locally as the ‘Big Oak’, this huge tree was already old when John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, preached beneath its branches in October 1749. The tree later survived the freak "Peckforton Cyclone", a tornado which occurred on the evening of 27th October 1913. According to a contemporary eyewitness, "a dark column of spinning air approached from the south, accompanied by thunder, lightning and torrential rain". During "four violent hours", Castlegate Farm, below Beeston Castle, lost its roof, hundreds of mature trees were uprooted, several cattle were hurled over a hedge: three of the cattle were killed, and a local man was hurled sixty metres into his neighbour’s orchard. As reported at the time:

- "The storm in Cheshire destroyed Lord Tollemache's extensive greenhouses at Peckforton Castle, while on the hill opposite hundreds of trees were uprooted. “According to most accounts the storm lasted two or three minutes only.”

In fact, the "storm" lasted for at least five hours, but moved quickly and spent only a few minutes at each place. The storm responsible was first noted in South Devon at 1600 on Monday 27 October 1913 and it tracked more or less NNE, as far north as Cheshire where it passed Runcorn at approximately 2100, heading into Lancashire. Six people were killed in South Wales. The storm tracked along its course leaving scores injured and much property damaged. The windspeed was not recorded, as no weather stations in the affected area seem to have had an anemometer and estimates of its strength are thus based on damage done. Changes in air pressure, however, were recorded in several places. They revealed a sudden fall followed by a return to the previous pressure after an interval of fifteen to thirty minutes. The Albion Steam Coal Colliery, at Cilfynydd, was situated within a few metres of the western edge of the tornado track and a drop in pressure from 29.20 to 28.91 inches (988.8 to 979.0 millibars), was recorded. It was followed by an almost immediate rise.

Mr. H. Billet of the Meteorological Office, at the request of the M.P. for East Glamorganshire, Clement Edwards, was sent to the region visited by the storm and spent three days in South Wales collecting information. His report was published in September 1914 as a Geophysical Memoir. The Met office investigators stated:

- "This fall of 0.3 inch, or 1/100 of the normal atmospheric pressure of 15lbs to the square inch, means a sudden change in the atmospheric pressure of 0.15 lb per square inch, or about 20 lbs per square foot. Such a change of pressure, if applied suddenly to the outside of a closed building, must produce an effect similar to an explosion within, and it is thus easy to understand how windows or even whole walls are blown outwards, as at the generating station at Treforest".

Actually, to shatter buildings in this way the peak overpressure might have been as high as 3 psi, with wind speeds possibly over 102mph. The Met Office investigation concluded with these points:

- ". . . a genuine tornado of the type common enough in parts of America . . . The straight track with clean cut lateral limits, the violent electrical phenomena, the heavy rainfall, the roaring noise, the sudden decrease of barometric pressure, resulting in the blowing out of walls of buildings, as if by explosion from within, are all features which are common in descriptions of American tornadoes. The width of the track, three hundred yards and the rate of advance, 36 miles per hour, are of the same magnitude as in American tornadoes".

Peckforton Mere

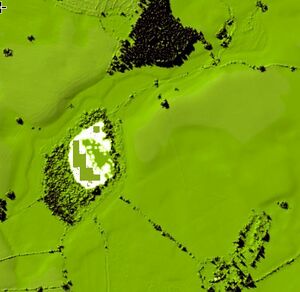

The "fort" at Peckforton Mere used to be much larger during the prehistoric period and the promontory to the east of it which houses the fort would have jutted out into it. The signage at the mere explains that the mere was formed as a "kettle hole" when an iceberg was grounded during some kind of fluvial event in the ice-age.

The River Gowy originally flowed out of the mere on the north side and this formed the northern defence of the fort. The present stream course lies further north than the original river and has been diverted by recent drainage operations. The fort has a bank and external ditch cutting off a piece of high ground which used to be a promontory and curving around it on the north and south sides, leaving the west side open to be defended in antiquity by the mere and the old course of the Gowy. The original bank and ditch are only partially visible as upstanding earthworks and can only be made out on the LIDAR with some difficulty, although the shape of the promontory is fairly clear. The fort, thought to be iron age, survives reasonably well in spite of the ploughing which has reduced some of its defences. It is small compared to a very similar site at Oakmere in Cheshire. The enclosed area is enough to support a collection of buildings for a single family settlement rather than a larger farming village.

Beeston

Beeston Crag, on which Beeston Castle is built, is one of a chain of rocky hills stretching across the Cheshire Plain. Like the neighbouring Peckforton Hills it is formed from easterly dipping layers of sandstone of Triassic age, part of a thicker sequence known as the New Red Sandstone. The lower slopes of the hill are formed from sandstones of the Wilmslow Sandstone Formation whilst those above are formed from the Helsby Sandstone Formation which is around 245 million years old. Both sandstones were quarried at multiple sites within the castle grounds but these workings are long abandoned. The hill is capped by a small outcrop of sandstones assigned to the Tarporley Siltstone Formation (and formerly known as the Keuper Waterstones).

Along the eastern margin of the hill is the Peckforton Fault, a major north-south aligned geological fault which downthrows the strata to the east by about 200m. A low ridge of glacial moraine extends east from the castle lodge and is interpreted as marking an ice front during the retreat (or stagnation in situ) of the Irish Sea ice sheet which had invaded Cheshire from the northwest during the last ice age. To avoid this moraine the Gowy takes a detour to the east.

Pits dating from the 4th millennium BC indicate the site of Beeston Castle was inhabited or used as a communal gathering place during the Neolithic period. Archaeologists have discovered Neolithic flint arrow heads on the crag, as well as the remains of a Bronze Age community, and of an Iron Age hill fort. The rampart associated with the Bronze Age activity on the crag has been dated to around 1270–830 BC; seven circular buildings were identified as being either late Bronze Age or early Iron Age in origin. It may have been a specialist metalworking site.

There are many legends surrounding Beeston Castle. Local legend holds that Richard II hid his extensive Royal Treasure hereabouts before sailing to Ireland to quell an uprising in 1399. Richard never reclaimed his treasure as he was captured, upon his return, at Flint by Henry Bollingbrooke (Duke of Lancaster, and later Henry IV) and imprisoned at Chester Castle for a while in 1399. Many attempts have been made to find the "treasure" over the years and none of them have been successful. Stories have suggested that there are "secret" passageways leading from the well to a nearby farmhouse, a possible escape or re-supply route if the castle was under siege. Local legends place the treasure at the foot of the castle well (said to be around 365 feet deep - an impressive feat of mediaeval engineering) or in passages running off the well. Other tales tell of "demons" guarding the treasure in the well, the sight of which would instantly drive the beholder mad or strike them dumb. However the well has been explored by camera and neither demons nor treasure were encountered.

The river's redirection

The course of the Gowy can be traced on the 1908 OS map and also on a map from 1829--31. What is very clear from a comparison of the two maps is that the the course of the Gowy appears to have been modified such that it now flows through the hamlet of Beeston. The tithe map seems to suggest that this redirection was done before 1846.

Haycroft is a deserted medieval village in the civil parish of Spurstow, located at SJ5553157178, immediately east of Haycroft farm. They were discovered by aerial photography. The remains appear to be concentrated to the north east and south west of a former watercourse which ran down a shallow valley to the north west of the present village of Spurstow, flowing into the original course of the Gowy and thence to Bunbury. These remains were probably part of the village of Spurstow which has shrunk or slightly relocated in the post-medieval period. The earthworks include the platforms, 25–40 metres2 in area, for about six houses with adjoining enclosures. A raised feature, bisecting the site and running north-south across the settlement is a causeway which has been built up in more recent times to provide dry access. It follows the line of a former field boundary. Each house platform is between 25 metres and 40 metres square with a ditch 2 metres wide to define it. Each of these platforms would have been occupied by one or more medieval buildings. The settlement may have fronted the present lane running south east from the farm. This was a former route from Ridley Green to Beeston Moss and Beeston Castle. There are traces of medieval ridge and furrow in the northern part of the site and these run up to but not into the area of house platforms. The ridge and furrow is interpreted as the remains of the field system associated with the medieval village. The site is a scheduled monument.

The village of Spurstow is mentioned in the Domesday survey. The area was historically important in salt extraction, with an 18th-century brine spa known as Spurstow White Water or Spurstow Spa, which is rich in magnesium sulphate (Epsom salts). This was credited with health-giving effects. The spa still existed in the mid-19th century and can still be found today. Bath House is a half-timbered house in Lower Spurstow, dating from the late 16th century, which might have housed visitors to the nearby spring. The eventual destination of the water flowing from the spring is the River Weaver.

The "real" Image House

The Image House is at the corner of the A49 and Betty's lane. This features in "The Shiny Night" by Beatrice Tunstall. The story, supposedly based on "one of the very few real events of witchcraft in Cheshire", is about a young poacher named Seth Shone who in some versions kills a gamekeeper, is transported to Botany Bay for eight years (or in some versions seven years), returns to "Clock Abbot", as Bunbury is called in the book, and sets about getting his revenge on his enemies. These enemies are some combination of the local squire, his gamekeeper, several of his men or the local constable depending on the version. He makes images of them, names them and curses them violently, and places these "Voodoo dolls" on the walls of his house for all to see. The house still has a porch supported on carved oak posts with sandstone heads as caps and stone carved male figures, wearing hats, which flank the first floor windows. Beatrice Tunstall, author of The Shiny Night (1931), The Long Day Closes (1934) and The Dark Lady (1939) had her home on the walls of Chester near the Northgate.

The present cottage, is dated early C19, of red brick in Flemish Bond with a slate roof, on two storeys, with 2 bays, and lean-to additions to south gable and a rear (west) sandstone plinth. The boarded door in the front porch is supported on carved oak posts with sandstone heads as caps. There are stone carved male figures, wearing hats, which flank the first floor windows. The 1839 Tithe maps have a different layout of buildings on the site (with a single building) and have the land owned by John Tollemanch and a cottage in the tennancy of Robert Vickers.

There are a few problems with the legend as recorded. "Botany Bay" was intended as a penal colony in 1788, but the site offered neither a secure anchorage nor a reliable source of freshwater. Sydney Cove offered both of these, being serviced by a freshwater creek and so that was settled instead: in fact the actual book has him in Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania) and returning before 1837. A part of the legend is that Shone was able to build the house in a day and have a fire lit in the hearth. "Tŷ unnos" (pl.: tai unnos; English: one night house, also hafodunnos) is an old Welsh tradition that has parallels in other folk traditions in other areas of the British Isles. It was believed by some that if a person could build a house on common land in one night, the land then belonged to them as a freehold. There are other variations on this tradition, for example that the test was to have a fire burning in the hearth by the following morning and the squatter could then extend the land around by the distance they could throw an axe from the four corners of the house. There are several problems with this aspect of the tale: Tŷ unnos has no status in English common law and a two-storey brick house cannot be built in a day (even with "the help of friends") as the mortar in the lower walls would not set quickly enough.

Seth's curse apparently backfires on him with the 1865-66 "Rinderpest" epidemic. This did affect the area seriously, placing the county of Cheshire in debt for thiry years, although landlord Tollemanch apparently did a good deal to help out those affected.

Bunbury

- "BUNBURY, a township, a parish, and a subdistrict in the district of Nantwich, Cheshire. The township lies on the Chester canal and the Chester and Crewe railway, near the Calveley station, 3½ miles SSE of Tarporley; and it has a post office‡ of the name of Higher Bunbury, under Tarporley, and fairs on 11 and 12 Feb., and 30 and 31 July. Acres, 1,140. Real property, £4,229. Pop., 990. Houses, 209. The parish contains also the townships of Tiverton, Tilstone-Fearnall, Beeston, Alpraham, Calveley, Wardle, Haughton, Spurstow, Ridley, Peckforton, and Burwardsley. Acres, 16,830. Real property, £28,879. Pop., 4,727. Houses, 927. The manor belonged to Hugh Lupus; and passed to the Bunburys. A college for a master and six chaplains was founded here, in 1386, by Sir Hugh de Calveley; and was purchased from the Crown, in the time of Elizabeth, by Thomas Aldersey of London, who gave the income for charitable uses. The living is a vicarage, united with the p. curacies of Peckforton and Calveley, in the diocese of Chester. Value, £117.* Patrons, the Haberdashers' Company. The church is later English; has a side chapel and a pinnacled tower; was injured by the royalists in 1643; underwent complete restoration in 1865; and contains monuments of Calveley, the Cheshire hero of the 14th century, and Beeston, the commander against the Spanish armada. The p. curacies of Tilstone and Burwardsley are separate benefices. There are seven dissenting chapels, two national schools, and charities £46.-The subdistrict contains three parishes and part of another. Pop., 7,959." - John Marius Wilson's Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales (1870-72)

Archaeology suggests almost continuous occupation of the site since very early times. Bunbury was reputedly derived from Buna-burh, meaning the "redoubt of Buna". Just prior to 1066 it was held by a certain Dedol of Tiverton. It was listed as Boleberie in the Domesday Survey of 1086 and the lord of the fief was Robert FitzHugh. A Norman family later acquired the surname of De Boneberi, during and after the reign of King Stephen. They were allegedly a cadet line of the Norman family of De St Pierre, associated with Hugh of Avranches, Earl of Chester. Much later, in the era of the English Civil War and on the date of 23 December 1642 some of the prominent gentlemen of Cheshire met in Bunbury and drew up the Bunbury Agreement (see below). The terms of the agreement were intended to keep Cheshire neutral during the English Civil War. It proved to be a forlorn hope because the national strategic importance of Cheshire and the city port of Chester meant that national interests overruled local ones.

Bunbury was a victim of the Blitz during World War II. German aircraft returning from a night raid on Liverpool in 1940 jettisoned surplus bombs over the village, obliterating Church Row (the houses have since been rebuilt). The blast caused minor damage to the exterior of St Boniface's Church and the immediate area. The original village centre surrounding the church was hit, damaging shops beyond repair. This has largely caused the current centre to evolve in the geographical heart of the village. Bunbury was used as the location for Home Fires (known in the series as Great Paxford), a television drama.

There have been many descriptions of Bunbury Church written over the years. One of the earlier being that of Rylands and Beazley. Other are referenced on the Church Website. Rylands notes one tomb which has an interesting link to Chester. It bears the inscription:

- "George Lowe into rest November 24, 1876 | aged 83 years entered [a textfollows]. On the other side, in gothic letters: Beneath rest the mortal remains of | George Cliff Lowe | born October 5th-1821 and died at Newhaven, U.S.A., August 17th-1872. |"

The Lowe family of Chester were noted goldsmiths with a shop in Bridge Street (it is still there in 2020 and contains a small family museum). They were also at times Clockmakers and Rylands notes that George (1793- 1876) was a goldsmith at Gloucester, and subsequently went to live at Bunbury; he repaired the Ridley Chapel, and, in 1873, gave a new clock to the church in memory of his son George Cliff Lowe. A later member of the Lowe family was to decide to run away to sea rather than join the family business: he was Harold Lowe (21 November 1882 – 12 May 1944) the fifth officer of the RMS Titanic.

Hugh Calveley

Sir Hugh Calveley - whose tomb (one of the best of its time) is here although he may not be, was born the youngest son of David de Calveley of Lea, and his wife, Joanna. The family held the manor of Calveley in Bunbury. Estimates of the year of his birth range from 1315 to 1333. It is possible that he was a close relative, maybe even a half-brother, of Sir Robert Knollys. Along with many other Englishmen, the young Hugh Calveley served in Brittany, supporting Jean de Montfort's English-backed bid to become Duke of Brittany against the French-backed claimant, Charles de Blois, during the Breton War of Succession. An anonymous Breton poet's account of the Combat of the Thirty in 1351 has "Hue de Caverle" as a knight fighting on the English side (where he was defeated, captured, to be ransomed later). One estimate of the date of his knighthood is 1346, though documents from 1354 do not refer to him as a knight, and there is some evidence that he was only knighted later, in 1361. In 1359 Sir Robert Knollys and Calveley invaded the Rhône Valley. The city of Le Puy fell to them in July. The campaign ended when their way to Avignon was barred by the army of Thomas de la Marche, Deputy for Louis II, Duke of Bourbon, at which point both English commanders retreated. At the Battle of Auray on 29 September 1364, Calveley had the command of the reserve division of the forces of Jean de Montfort, under the command of Sir John Chandos. Charles de Blois was killed at Auray, enabling Jean de Montfort to claim the Duchy without further conflict.

After the conclusion of the Breton civil war, Calveley, along with many other soldiers, found himself unemployed. These soldiers, banding together in the "Free Companies" (i.e. mercenaries), continued to support themselves by raiding widely, causing a huge problem for the Kingdom of France. The solution to the problem was found when Aragon, France and the Papacy agreed to provide money to pay for the Free Companies to wage a campaign to support Count Enrique of Trastamara's bid for the throne of Castile, which at the time was held by Enrique's half-brother, Pedro of Castile. Calveley signed up as the most prominent of the English captains on this campaign, in which he was involved from 1365 to 1367. When hostilities resumed between England and France in 1369, Calveley was once again involved, first in raiding the possessions of Gascon nobles who had defected to the French. He took part in at least three further campaigns in the period to 1374; notably, he was one of the joint commanders of the English army disastrously defeated by Bertrand du Guesclin at the Battle of Pontvallain, 4 December 1370, though he managed to escape. From 1375 to 1378, Calveley was governor of Calais, an important port. Thereafter, he became one of the two Admirals of the English fleet, taking part in several sea battles. In July 1379, he was involved in a raid on Brittany led by Sir John Arundel, Marshal of England. On their return voyage, 20 ships and about 1000 men were lost at sea in a storm. Calveley was one of only 8 survivors.

There is no clear evidence for or against Calveley being buried at Bunbury, and the tomb may be merely a cenotaph erected by his campaign companion (and probably close relative), Sir Robert Knollys. There is a memorial board on the north wall of the chancel to Dame Mary Calveley (d. 1705) with an inscription wrich referes to money being left to "sweep and make clean" the monument under which she and her husband are interred. In an attempt to clarify this uncertainty the tomb was opened on 25 April 1848, and according to Jno.Fenna, Churchwarden:

- "I found the fragments of an oak coffin, apparently of uncommon size, almost crumbled to dust; the handles of the sides being iron were nearly entire. By the side of his coffin lay a lead coffin quite fresh, with the initials D.M.C. which I suppose to be that of Dame Mary Calveley. I measured some of the bones, which I have no doubt were Sir Hugh's, from their extraordinary size, . . the thigh-bone, was two inches or more larger than the average size of men. He is supposed to have measured seven feet six inches in height when he lived. There is a mark on the wall in Bunbury Church [probably lost in the 1865 restoration] which old people say was the memorandum of his height."

Despite the above statement, later historians (after Bridge, 1908) consider the bones

- “were quite clearly those of Dame Mary Calveley (ob.1705) and her husband, another Sir Hugh Calveley (ob.1648).”

This later Mary Calveley built Bridge House in Lower Bridge Street, Chester after the death of her husband left her a young and very wealthy widow.

George Beeston - Elizabethan Sea-Captain

The manor of Beeston, but not the castle, was owned by the de Bunburys, who later took the name Beeston. Sir George Beeston (1500-1801, who has a memorial in St Boniface's Church, Bunbury) was, again acccording to local legend, commander (at the age of 89 if Ormerod is to be believd) of the Dreadnought at the time of the Spanish Armada in 1588. In fact, Sir George Beeston was only born in 1520, although he did command the Dreadnought. In February 1588, at Queenborough, he commanded the four ‘great ships’ that were to sail with Charles Howard, 2nd Lord Howard of Effingham, and after the Armada battle he was knighted by Howard on board the Ark Royal. The latin inscription on his tomb may be translated as:

- "Here lies buried George Beeston, knight, a promoter of valour and truth; having been brought up from his youth in the arts of war he was chosen one of his company of pensioners by the invincible King Henry the Eighth, when he besieged Boulogne [1544]; he merited [the same] under Edward the Sixth in the battle against the Scots at Musselburgh [1547]. Afterwards under the same King, under Mary, and under Elizabeth, in the naval engagements as captain or vice-captain of the fleet, by whom, after that most mighty Spanish fleet of 1588, had been vanquished, he was honoured with the order of knighthood; and now, his years pressing heavily on him, when he had admirably approved his integrity to princes, and his bravery to his adversaries, acceptable to God, and dear to good men, and long expecting Christ, in the year 1601 and in the ... of his age, he fell asleep in Him, so that he may rise again in Him with joy. And together with him rests a most beloved wife, Alice, daughter of [Thomas] Davenport of Henbury, esquire, a matron most holy, chaste, and liberal to the poor, who, when she had lived in matrimony 66 years, and had borne to her husband three sons, John, Hugh, and Hugh, and as many daughters, Ann, Jane, and Dorothy, passed into the heavenly country in the year 1591 and in the [refer below] year of her age, with Christ for ever to live. The dutifulness of their son Hugh Beeston, esquire, the younger, Receiver General of all the revenues of the Crown as well as in the county palatine of Chester as in the counties of North Wales, set up this monument to parents most excellent and beloved."

Bunbury Mill

The mill has quite an interesting history, because it is said that there has been a corn mill on the site as far back as 1290. Bunbury is the only mill on the Gowy which is an overshot mill, as it it the only place where the gradient is steep enough. The other mills are less powerful undershot mills. The present building dates from about 1844, when an earlier mill was apparently destroyed by fire. Curiously, the 1839 Tithe map does not indicate the clear presence of an active mill but refers to the "site of the mill pool" and has the mill buildings marked as a house and garden owned by Sir Thomas Champness and occupied by a William Fenna. A William Fenna was churchwarden at Bunbury in 1718 (he is associated with the provision of the church candelabra) and the Fenna's seem to have been a moderately prosperous local family. The 1908 OS map gets the direction of the Gowy completely confused with the river flowing out of the mill pond in both directions.

The mill was initially used to produce flour and animal feed. Bad flooding occurred in 1960, when there was a violent storm, which amongst other things, uprooted trees close to the mill and blocked the weir gate. The miller, Tom Parker, whose name still appears on the outside of the building, was unable to free the tree, and the build-up of water eventually burst the millpond wall, flooding the mill and wrecking the machinery. This forced the mill to close, as renovations would have been far too costly, and the products were no longer in high demand.

Nantwich Rural District Council bought the site to use it for water treatment. It was supposed to be destroyed 6 years later, but the locals gathered to protest, as they wanted the mill to be repaired, not only for reasons of heritage, but also to create more jobs in the area. By 1977, Bunbury Mill was back up and running. But this time it was owned by North West Water Authority, part of United Utilities, which is the organization that first turned it into a museum and education centre. The mill closed once again in 2010, but volunteers were kind enough to keep an eye on the machinery, and make sure everything was in working order. The Bunbury Watermill Trust was then established, and in April 2012 the mill was given to the Trust, reopening it to visitors. The group Friends of Bunbury Mill has been established to support the work of the trustees. Tours of the working mill are available. The site includes the mill pond, a wildlife pool and 2 acres of grounds. Facilities include a picnic area and a visitor centre with a café and public toilets. There are many other listed buildings in Bunbury.

Bunbury School

The school was built in 1874 and designed by the Chester architect John Douglas. It was built as a grammar school to replace a school nearer to Bunbury Church, which had been founded in 1594 by Thomas Aldersey. It later became a primary school. Aldersey was born in Bunbury. His father, John Aldersey (c. 1494–1554) of Aldersey Hall, was a landowner from Spurstow. His mother, Anne (or Agnes), was the daughter of Thomas Bird of Clutton or Colton. Several members of the Aldersey family were prominent in 16th-century Chester. Thomas Aldersey was the second of several sons of the marriage. He was educated in Bunbury, possibly at the Chantry House. Aldersey was apprenticed to the London merchant Thomas Bingham in 1541, becoming a liveried member of the Worshipful Company of Haberdashers on 13 July 1548. Exposure to Protestant Reformist speakers in London, including Christopher Goodman and Jan Łaski, led him to become a Protestant. Mary I's accession in 1553 made his religious and political convictions dangerous, and in 1555 he was charged over his attention to Goodman's writings. His efforts, which continued throughout his life, to aid the Protestant exiles who left England for Emden in Germany in establishing trading relationships gained him the support of William Cecil and other prominent Protestants. Christopher Goodman would eventually return to Chester and was instrumental in getting the Chester Mystery Plays banned.

Aldersey founded a grammar school at Bunbury in 1575, which was incorporated on 2 January 1594 as "The Free Grammar School of Thomas Aldersey in Bunbury" – now Bunbury Aldersey School. He gave the school, together with substantial endowments, over to the Company of Haberdashers on 21 October 1594. It was the first school that the Company – now predominantly an educational charity – administered. At the same time, he established a preacher and curate in Bunbury, and gave the tithes and advowson (patronage) of the parish church to the Haberdashers' Company; this was the first ecclesiastical living to come under the Company's control. Dorothy Williams Whitney has suggested that this gift was associated with the later Puritanism of the Company of Haberdashers, and Bunbury became an early centre for Cheshire nonconformism amongst clerics (the village itself was quite strongly catholic - in 1590, 23 residents of Bunbury were Catholic recusants, a figure rising to 37 in 1593 but dwindling to approximately six by 1789). It would be William Hinde of Bunbury that would write the life of John Bruen the Tarvin iconoclast. Hinde was a leader of the Puritans in Cheshire, and clashed with Thomas Morton as bishop of Chester. Hinde died at Bunbury in June 1629, and was buried there.

Edward Burghall

Perhaps one of the most interesting facts about Beeston relates to the diary of Edward Burghall, then the Puritan schoolmaster of Bunbury who supposedly records the fate of the unfortunate Captain Steel of Beeston Castle in 1643/4 which had always been taken as a primary source. Already Before the civil war Burghall was schoolmaster at Bunbury, and was probably appointed to the post about 1632. The parish school at Bunbury, of which Burghall was master, was founded in 1594, and was endowed with "£20 per annum, one house and some land". The vicar of Bunbury till the year 1629 was William Hinde, a celebrated puritan and biographer of John Bruen. In 1643, during the siege of Nantwich, Burghall says that his goods were seized and himself driven from his home by Colonel Marrow; he thereupon went to Haslington in Cheshire, "where he had a call", and tarried there from 1 May 1644 until 1646. In the latter year he became vicar of Acton, taking the place of Hunt, who was sequestered. After the Restoration, when the Act of Uniformity 1662 was passed, Burghall was one of the victims of the Great Ejection. After preaching farewell sermons at his churches of Wrenbury and Acton, he was on 3 October 1662 suspended from the vicarage of Acton. Before the civil war the entries only record what the author regarded as the special interventions of Providence in the neighbourhood of Bunbury. In the year 1641 Burghall first notices political events, and afterwards gives a very detailed account of the military operations in Cheshire.

However when James Hall was preparing his "History of Nantwich" he discovered that parts of the supposed "diary" are a virtual copy of the diary of Thomas Malbon of Nantwich (actually written in 1651) and Edward Burghall (who died in poverty in 1665) is essentially a forger as regards at least some parts of his supposed diary. See Hall's Memorials of the Civil War for a comparison between the two works. Edward Burghall's memorial is Bunbury's St. Boniface Church (built 1386), whereupon he is decribed as a "Paineful Schoole Mr".

As noted above, it has been suggested that the stone elephant at Peckforton had something to do with the Haberdasher's Company, whose arms contained an elephant and castle, but no firm link has been established.

There are typical country ghost legends: a phantom dog (shuck) has been supposedly been spotted in an area near the school and a ghostly man on horseback is said to cross various lanes before vanishing. There are no details to these legends.

The Bunbury Agreement

At the start of the First English Civil War, after a summer of skirmishes in Cheshire, the sometime pirate Henry Mainwaring and Mr. Marbury of Marbury Hall (for Parliament) and Lord Kilmorey and Sir Orlando Bridgeman, son of the Bishop of Chester (for the Royalists) agreed to meet on December 23rd 1642 at Bunbury. It must have been clear to all that families were deeply divided on both sides of the conflict and that Cheshire would be devastated by full-scale war.

In the so-called "Bunbury Agreement", they agreed that all fighting in Cheshire would end. All prisoners would be released, property taken during the conflict returned to its owners and any losses compensated by a levy on both sides. Fortifications were to be removed at Chester, Nantwich, Stockport, Knutsford and Northwich and their combined forces would escort any external forces out of the county. Both parties agreed that there were to be no further troop movements through Cheshire, and that they would not to raise any more troops locally. Everything depending on the agreement of their national commanders, whom they would urge to settle their differences peacefully.

Given the national strategic importance of Cheshire, it proved impossible for the local gentry to agree a local neutrality pact that their national commanders would agree to. Geographically Cheshire lies between the Pennines and the north Welsh foothills and so whoever controlled Cheshire controlled the western route to north west England and Scotland as well as an important route into north Wales. For Parliament the control of Cheshire would mean separating the King's northern supporters from the King and his army at Oxford. It could also stop the King bringing in reinforcements from his Irish army through the port of Chester. During the summer the King's supporters had not been idle and Chester's defences had been strengthened with the Commissioners of Array arranging to man the defences. In addition the city's corporation raised an additional 300 men to assist them, that were paid for by a monthly assessment (local tax) on all inhabitants. These preparations continued in December when the corporation raised more money through another assessment for additional weapons and fortifications.

Unfortunately this Bunbury Agreement was never to be ratified.

Tilstone

- "TILSTON-FERNALL, a township in that part of the parish of BUNBURY which is in the first division of the hundred of EDDISBURY, county palatine of CHESTER, 2¾ miles (S. S. E.) from Tarporley, containing 166 inhabitants.": Samuel Lewis - A Topographical Dictionary of England (1831)

Even just before the start of of the Industrial Revolution, improvements to the river Weaver after 1730 served to channel trade from central Cheshire away from Chester to the Mersey, and the Trent and Mersey Canal Act of 1766 threatened to strengthen still further the dominance of Liverpool over the Dee. Despite that threat, no apparent opposition to the Trent and Mersey Bill was voiced in Chester, but within two years of its passage there was a proposal for a canal to link Chester to the new canal at Middlewich and surveys were commissioned from, among others, the canal engineer James Brindley. The original plan for the Chester Canal was for a canal linking the south Cheshire town of Middlewich on the Trent and Mersey Canal with the River Dee at Chester, with a branch to Nantwich, providing a route for produce (including salt) from Nantwich to reach Chester and, beyond it, the sea via the Dee Navigation of 1737. The relevant section of the Trent and Mersey would be open in 1771, although the final (tunnel) section to the Potteries was not completed until 1777. However there were difficulties with the Trent and Mersey Canal Company, and its owner the Duke of Bridgewater, who were jealous of their own lucrative traffic and put up a prolonged and robust opposition to any link with the proposed Chester Canal.

The limited plan authorised 1772 permitted the building of a canal 14 feet wide from Chester to Nantwich and Middlewich. This had immediate effects on Chester: Queen Street having been constructed fairly rapidly around 1777, with much development by two individuals in particular: John Chamberlaine (who was much involved with the canal) and Roger Rogerson. The development of the street was obviously also connected with the development of the Chester-Nantwich canal. From the 1770s city development was especially concentrated north of Foregate Street, beginning with Queen Street and expanding later to include Bold Square and Seller and Egerton Streets before 1820. The overall canal project was seriously undermined, however, by a requirement that the new canal should end at least 100 yards away from the Trent and Mersey Canal at Middlewich, requiring overland portage rather than allowing for a functional junction. As a result, the Middlewich branch of the Chester Canal was not begun, and the branch to Nantwich became the course of the final section of the Chester Canal.

By late 1777, the canal company had spent all of the share capital of £42,000 and another £19,000, which had been raised as a loan guaranteed by Samuel Egerton of Tatton. He was a shareholder in the company and related to the Duke of Bridgewater. They applied for another Act of Parliament, which allowed them to raise another £25,000, by additional calls on existing shareholders, and to borrow £30,000 as a mortgage. They succeeded in raising £6,000 by making additional calls, and borrowed £4,000 from Richard Reynolds, an ironmaster from Ketley, who was responsible for several of the East Shropshire Canals, including the Wombridge Canal and the Ketley Canal. Shareholders who could not provide funds on the additional calls found themselves deprived of their existing shares. When the canal between Chester and Nantwich opened in 1779, it was a dead end and attracted little traffic other than a moderately successful and fast passenger trade, leading to financial disaster for its backers who at one stage saw the share price in the canal company fall to 1% of the initial value. John Aikin wrote:

- "For want of money the branch to Middlewich was never cut; and thus the principal objects of the undertaking, the carriage of salt from that place to Chester, and the communication (though not the absolute junction) with the Grand Trunk being never effected, the sceme has proved more totally abortive than any other in the kingdom."

No dividends were paid during the canal company between 1772 and 1813. By the end of 1781, the company had no money and was unable to meet interest payments on the loans. They decided to forfeit the canal to Egerton, the main mortgagee, but he did not respond to their offer. Part of the canal was even abandonned in 1787, when Beeston staircase locks collapsed, and there was no money to fund repairs. By the end of the 18th Century, the Chester Canal was facing ruin, but was saved by a link with the Ellesmere Canal Company, which had been set up in the 1790s to link Ellesmere in Shropshire, and the quarries and other industries of North Wales, to the Mersey at Netherpool/Whitby, now known as Ellesmere Port. In Chester, the company built the section of canal known as the Wirral Line,which runs north to Ellesmere Port and which was completed in 1795.Historically, this was of great significance and represented a major upturn in the fortunes of the owners of the Chester Canal Company, which would probably not otherwise have survived. A further link between the Chester and Ellesmere Canals at Hurleston also meant that any problems over water supply were solved by the flow of water brought down from the Welsh Hills. By 1813, the partnership had been so successful that the two companies merged to create the Ellesmere and Chester Canal Company. In 1846, the Shropshire Union Railways & Canal Company (SURCCo) represented an amalgamation of a number of earlier canal ventures. The oldest of these was the Chester Canal, and it was only through mutually beneficial links with the Ellesmere Canal and then the Birmingham & Liverpool Junction Canal in the early 19th Century that commercial success was achieved and the SURCCo was formed, with a Head Office based in Chester in the buildings next to what is now Telford’s Warehouse. With an annual turnover from carrying of nearly £200,000, the company appeared to be performing quite well and showed a profit in most years, but this was an illusion, since it was dependent on subsidies from both the parent company LNWR and, during the Great War, from the government. The withdrawal of these subsidies in 1920/21, combined with an attempt to restrict the boatmen’s working day to "only" 8 hours plunged the company into massive losses and the decision was taken, quite abruptly, to withdraw from carrying alltogether and sell off the fleet.

A Mill for every Lock?

For the next few miles the Gowy and the Chester Canal run alongside each other. The construction of the canal provided a small head of water at each of the locks, but the mills did not make use of the by-washes. Co-incidently, many of the locks have at some time had mills associated with them even if there is often little to see on the ground today. It is possible to speculate as to why the locks and the mills are associated, although it may be co-incidence. The mills whould have been placed a distance apart to allow a head of water to build up, and were possibly located where the change in gradient also favoured a lock. The mills might have been located by bridges, which would facilitate the building of locks. If corn was not grown locally then distribution of corn by canal would influence the position of mills.

Tilstone Bank

At Tilstone Bank the Gowy meets up with the Chester Canal and the railway, which both make use of the River Gowy valley to cross through what is effectively a gap in the sandstone ridge of central Cheshire. This is the gap which Beeston Castle defends.

The landscape character type is unique within Cheshire West and Chester borough, defined by its complex rolling landform that falls steeply down to the River Gowy and the Shropshire Union Canal which pass east-west through the middle of the area. Sandstone outcrops in a series of escarpments and dip slopes create a distinctive locally hilly landscape occupying the gap between the Sandstone Ridge to the north and south. The topographic variations identify this as a separate character type from the surrounding more gently undulating farmland to the north and east,and the much flatter fields of the Cheshire plain to the south and west.

The settlement of Tilstone was an important crossing point of the River Gowy and Chester Canal. Tilstone Lodge dates from 1832 and was commissioned by Admiral Tollemache who retained the architect Thomas Harrison to design it. It is designed in the Georgian style and constructed of brick which is part rendered and has colour washed elevations under a slate roof incorporating a three-bay front flanked by a wing which is set back. After the Tollemache family moved across the Gowy to their new castle the property was bought by the Corbetts.

Murder

In 1857, the Tilstone Lodge gamekeeper John Bebbington, rose from his bed early one morning to make his rounds of the woods and pheasant preserves: he was found lying dead in a ditch, with his loaded gun beside him. In an adjacent field the police discovered two sets of footprints – one belonging to the gamekeeper and the other set they traced to John Blagg, 47, a shoemaker and poacher. At Blagg’s home they found a gun and cartridges supposedly matching the one that shot Bebbington. They also found the boots that had apparently made the footprints, although this was one of the first cases of such evidence being used and no-doubt much was made of the "shoemakers boots". Blagg had previously threatened the gamekeeper (while drunk) and despite his protestations he was arrested and charged with murder. He was probably held in the village "lock-up" (which still exists) in School Lane, Bunbury.

His counsel argued that all the evidence was circumstantial:

- "The poor man is a victim of hatred because he was a poacher; and as the prosecution could not get hold the real murderer, they pounced on the prisoner because he happened, unfortunately, to be disliked by a Cheshire country gentleman."