Earls of Chester

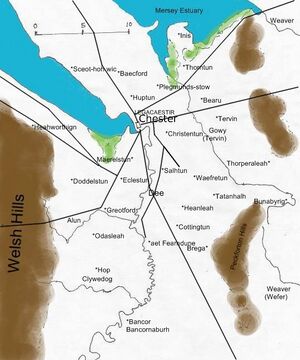

The "Earldom of Chester" long represented a power in England which was akin to a separate country, with its own legal system and courts, and an almost independent government.

The Creation of the Earldom of Chester

Pre-Roman History

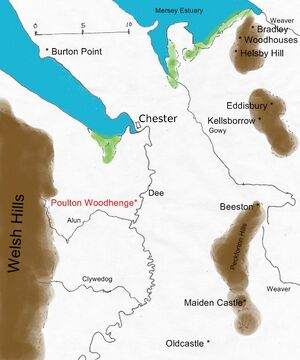

The primary agricultural use of the Cheshire Plain is, and has for a long time been, dairy farming. The clement weather, sheltered from the prevailing winds by the Welsh mountains, encouraged a pastoral existence. The Cornovii ("people of the horn") tribal lands encompassed the modern county of Shropshire along with considerable portions of southern Cheshire, western Staffordshire, the West Midlands and eastern Clwyd, also including small portions of north-east Powys and northern Hereford & Worcester. No pre-Roman tribal center has been identified with any clarity (the Wrekin been suggested) but the tribal lands are well-stocked with Iron-Age hill forts. Examples in the Frodsham Hill area alone include Eddisbury and Kelsborrow Castle. Despite this profusion of hill-top fortifications the tribe has left few ceramics, having no pottery industry to speak of. This points to the Cornovii leading a mainly pastoral lifestyle, where lightweight wooden bowls and utensils were used in preference to (easily broken) and heavier pottery vessels. The tribe is also remarkable in that it produced no coinage of its own. When the Romans arrived they did not encounter any local ruler worth mentioning.

Romans (see: Roman Chester)

The Romans positioned the larger than normal fortress high on a sandstone bluff above the marshes. The fortress covered 60.90 acres, 20% larger than those in York and Caerleon, which were founded at the same time. Free from the floods of winter and the ever-changing shorelines of the estuary, the bend in the River Dee provides protection on two sides – south and west. It is also the lowest bridgeable and fordable point on the River Dee before it becomes too wide and treacherous. Drinking water was piped in from a spring in the suburb of Boughton.

The fortress was designed in the standard "playing card" shape, with some modifications to the normal plan of buildings. It had four gates, corner towers and interval towers between the gates. The Roman gates had double arches and the Roman Eastgate had a statue of Mars, the Roman god of war, in the middle of the two arches. A fosse or ditch was dug around the north and east sides to provide extra protection. It has been calculated that the fortress was designed to accommodate 6,000 soldiers. The internal buildings consisted of barracks, baths, a hospital, a granary and some "headquarters" buildings. The main fortress baths were located halfway down the modern Bridge Street on the right-hand side.

Legio II built their fortress in the territory of the Cornovii. It soon became the main base for Legio XX Valeria Victrix, the 20th Legion, which used it as a port administration base and military fort. It was then one of the principal towns of Roman Britain.

Later on in the fortress's history, settlements began to develop outside the fortress walls between the west wall and the port area near the river. Mansion buildings were created for wealthy Romans outside the Walls, an example of which was discovered on Castle Street. Roman shops and workshops lined the incoming roads and to the south as far away as modern day Eccleston. A bath complex was established outside the fortress walls on the modern Watergate Street under the site now occupied by Sedan House.

The Roman fortress was occupied up to the 4th Century. Roman coins have been found in the area dating up to this time. The fortress was described as waste land in the 6th century. It is thought that some Roman buildings remained standing as late as the Norman period. This is the reason why Northgate Street is dog-legged in shape. A massive column base of the Roman 'principia' can be seen through the floor in the shop Blacks. Much of the Roman masonry was robbed out and reused in later periods.

A recent Timewatch investigation by the BBC speculated that, from the size and scale of the fort, had the Roman Empire not begun to collapse, Deva would have become the Roman capital of Britain and a launch post for invasions on Ireland. In fact, recent discoveries of a possible fort in Ireland (at Drumanagh in north Co. Dublin) suggest that at least one foray was made. Chester would have been ideally situated as a capital if the conquest if Ireland had gone ahead, but Roman policies changed from conquest to consolidation and the capital became London for commercial reasons.

During the latter half of the 3rd century, the Roman Empire faced a crisis. Internally weakened by civil wars, the violent succession of brief emperors, and secession in the provinces, it faced a new wave of attacks by "barbarian" tribes. Most of Britain had been a Roman province (Britannia) since the mid-1st century, protected from raids in the north by the Hadrianic and Antonine Walls, and by the Classis Britannica patrolling the Channel. As frontiers came under increasing external pressure, a "fortification" program was undertaken throughout the Empire to protect cities and other strategically important locations. At this time the forts of the Saxon Shore were built. As early as the 230s, under Severus Alexander, units were being withdrawn from the north and garrisoned at locations in the south. New forts were constructed at Brancaster, Caister-on-Sea and Reculver. Dover was already fortified since the early 2nd century. Between the 270s and 290s, the full chain of forts was completed. They would buy the Romano-British another 100 years. It appears that a coastal defence network was constructed along the coast of North Wales, with a small fort at Caer Gybi (Holyhead) on Angelsey and a series of forts (Caer) and signal towers along the Welsh coast at Hen Waliau (Caernafon), Bangor, Braich yr Dinas, Caerhun, Deganwy, Varis (St Asaph) and Pentre. Collingwood describes the new fortification at Caernafon as follows:

- "At Carnarvon, the lower fort, 150 yards west of the earlier fort, has its east wall complete, about 230 feet long; of the north and south walls about 120 and 180 feet remain. The walls are 5½ feet thick and up to 12 feet high; bastions were once visible. There are bonding-courses of flat stones and regular rows of put-log holes. The area was something over an acre, and the fort was probably a small Saxon Shore castellum (Segontium, 95)." (Collingwood, p.54)

Much more detail on the Romans in North Wales can be found on the Kanovium Project site. The defences of the "Irish Shore" may not have been as impressive as those of the Saxon Shore, but they would have given some comfort to the Romano -British of Gwynedd and Chester. In the longer term, they may well have helped to preserve Romano-British culture in Gwynedd while the rest of the Roman province of Britannia fell apart. Given the natural harbour at Chester there may well have been an Irish Sea equivalent of the "Count of the Saxon Shore" (Latin: comes littoris Saxonici per Britanniam) who was the head of the Saxon Shore military command of the later Roman Empire.

Dark Age Chester (see: Dark Ages)

The prototype of the Earl of Chester may have first emerged in the post-Roman era. Hollinshead (who is thought to have come from Cheshire) mentions an "Earl of Chester" in connection with the coming of the Saxons in the 5th century:

- Amongst other of the Britains, there was one Edol earle of Glocester, or (as other say) Chester, which got a stake out of an hedge, or else where, and with the same so defended himselfe and laid about him, that he slue 17 of the Saxons, and escaped to the towne of Ambrie, now called Salisburie, and so saued his owne life. Vortiger was taken and kept as prisoner by Hengist, till he was constreined to deliuer vnto Hengist thrée prouinces or countries of this realme, that is to say, Kent &Essex, or as some write, that part where the south Saxons after did inhabit, as Sussex and other: the third was the countrie where the Estangles planted themselues, which was in Norfolke and Suffolke. Then Hengist being in possession of those thrée prouinces, suffered Vortigerne to depart, &to be at his libertie.

- When this Aurelius Ambrosius had dispatched Vortigerne, and was now established king of the Britains, he made towards Yorke, and passing the Gal. Mon. riuer of Humber, incountred with the Saxons at a place called Maesbell, and ouerthrew them in a strong battell, from the which as Hengist was fléeing to haue saued himselfe, he was taken by Edoll earle of Glocester, or (as some say) Chester, and by him led to Conningsborrow, where he was beheaded by the counsell of Eldad then bishop of Colchester.

Edol (as earl of Chester) will turn up again in "The Birth of Merlin", a Jacobean play first performed in 1622. While the first printed edition of the play attributes the play to William Shakespeare and William Rowley, most scholars reject the attribution to Shakespeare and believe that the play is Rowley's, perhaps with a different collaborator. However ther is no real evidence that Edol existed as a historical figure.

Refering to the Battle of Chester in 616 a certain "Brocmale" is mentioned as Earl of Chester. Hollinshead writes thus:

- It chanced that he had espied before the battell ioined (as Beda saith) where a great number of the British priests were got aside into a place somewhat out of danger, that they might there make their intercession to God for the good spéed of their people, being then readie to giue battell to the Northumbers. Manie of them were of that famous monasterie of Bangor, in the which it is said, that there was such a number of moonks, that where they were diuided into seuen seuerall parts, with their seuerall gouernors appointed to haue rule ouer them, euerie of those parts conteined at the least thrée hundred persons, the which liued altogither by the labour of their hands. Manie therefore of those moonks hauing kept a solemne fast for thrée daies togither, were come to the armie with other to make praier, hauing for their defender one Brocmale or Broemael, earle (or consull as some call him) of Chester, which should preserue them (being giuen to praier) from the edge of the enimies swoord.

As with Edol, there is little actual evidence for the existence of Brocmale or the position of "Earl" of Chester.

In the late 7th century, a religious institution was founded on the present site of St Johns Church which later became the first cathedral. The body of St. Werburgh was removed from Hanbury in Staffordshire in 875 and, in order to save its desecration by Danish marauders, she was reburied in the Abbey of SS Peter & Paul in Chester (the present Cathedral). Her name is still remembered in St Werburgh's Street which passes alongside the cathedral, and near to the city walls.

In 837, Æthelwulf of Wessex (later to become Alfred The Great's father) held the Witenagemot (literally "meeting of the wise") in Chester, and, being crowned (in Kingston not Chester?), received at Chester the homage of tributary kings, "From Berwick to Kent." In 893 Vikings raided Chester, then 'a deserted city in Wirral'. Although that description has led to the assumption that the site was waste from the 7th to the early 10th century, it need not be so interpreted. The raid, which culminated in the Danes' occupying the city and being besieged there for two days while the English ravaged the surrounding districts, may well have been prompted by an awareness of the city's growing economic and strategic importance, lying as it did near a direct route between the already closely linked Scandinavian kingdoms of Dublin and York. In any case, such desertion as there was can have been only temporary. The area south of the legionary fortress was occupied by the late 9th century; in particular, a site at Lower Bridge Street has yielded the remains of a small sunken-featured hut, a late 9th-century brooch, and sherds of a Carolingian jar imported from northern France. Moreover, from c. 890 Chester is the most likely site of a mint known to have operated in north-west Mercia. By then, therefore, the city was presumably a place of some importance.

It was Alfred's daughter Æthelflæd Lady of the Mercians who built the new Saxon 'burh'. The Anglo-Saxons called Chester Ceaster or Legeceaster.

In 973, two years after his coronation at Bath, King Edgar came to Chester, where he held his court in a palace in a place now known as Edgar’s Field near the Old Dee Bridge in Handbridge. Taking the helm of a barge, he was rowed the short distance up the River Dee from Edgar’s Field to St Johns Church by six tributary kings called ‘reguli’ (the monk Henry Bradshaw records he was rowed by eight kings). The kings' names are given as Kynath, King of Scots; James, King of Galloway; Maccon, King of Man, Malcolm and Inkil, Kings of Cumberland; Sifreth and Hywal, Kings of North Wales; and Dufnal, King of South Wales. The kings then swore fealty and allegiance to him at a service at St Johns Church, and then rowed him back to the palace. The event was recorded by Ranulph Higden, a monk of St. Werburgh's Abbey in Chester and it is also mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle:

- "In this year Prince Edgar was consecrated king on Whit Sunday at Bath, in the thirteenth year after his accession when he was twenty nine years old. Soon after this, the king led all his fleet to Chester, and there six kings came to him, to make their submission, and pledged themselves to be his fellow workers, by sea and land."

With two kings coming to Chester to have their ruler-ship confirmed, it appears that by the late tenth century Chester was a place of some importance. Perhaps it's use for this purpose was also was the fact that it was a port, and therefore that various sub-Kings could arrive for the ceremony by ship. Chester was the administrative as well as the military centre for the district involved in its maintenance as a royal fortress. Above all, it was the site of the court for a shire which may have originated in the early 10th century and certainly existed by 980.

The House of Leofric

During the 10th century Chester became well established as a major Mercian port and appears to have been the only sizable port in the region. From the 990s the family of Leofwine of Mercia settled in Chester and helped to ensure the city's survival as a major provincial centre. Leofwine was an "Ealdorman". Towards the end of the tenth century, the term ealdorman gradually disappeared as it gave way to eorl, probably under the influence of the Danish term jarl, which evolved into modern English earl. The analogous term is sometimes count, from the French comte, derived from the Latin comes. The ealdormen can be thought of as the early English earls, for their ealdormanries (singular ealdormanry, same meaning as earldom) eventually became the great earldoms of Anglo-Danish and Anglo-Norman England.

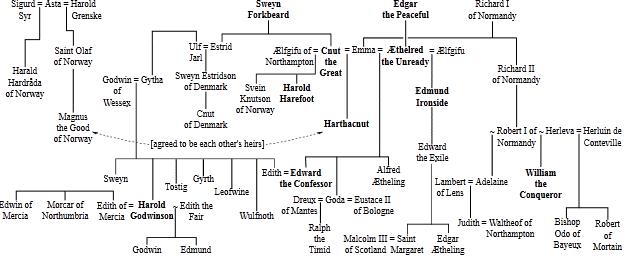

Leofwine's son Leofric (married to the famous Godifa) was known as the "earl of Chester" (or "count of Chester") and used a double-headed eagle as his personal device: - this ancient symbol has been adopted by various units of the British Army as a symbol for Mercia - including the Mercian Regiment which was formed from the "Cheshires". Curiously, it has also been suggested (with little basis in fact) that this Saxon earl of Chester was the father of Hereward the Wake. It is however well established that Leofric's grand-daughter, Ealdgyth married firstly the Welsh prince Gruffyd(also known as "King Of The Britons" - killed 1063), and secondly in spring 1066 to Harold Godwinson (Harold II - killed 1066, Hastings) - Harold complicates matters by having a mistress also called Ealdgyth.

Leofrics Mercian House was the only real rival to Wessex. Leofric's outlawed son, Ælfgar (who had a bit of a "history" with Harold), raided Mercia with help from the Welsh and particularly Gruffyd. In retaliation Harold and his - soon to be treacherous - brother Tostig subjugated Wales in 1063. After the death of Gruffyd, (at the hands of his own men) his half-brothers Bleddyn ap Cynfyn and Rhiwallon came to an agreement with Harold regarding the rulership of Wales and were given the rule of Gwynedd and Powys (they were later (in 1069-70) to rebel, with Eadric the Wild and the men of Chester, against the Normans). When Harold married Ealdgyth he not only married the widow of his enemy Gruffyd, but also the daughter of his enemy Ælfgar (who had died in 1o62). Ælfgar sons were Edwin, Earl of Mercia, and Morcar, Earl of Northumbria.

Harold marrying the Ealdgyth (widow of the Welsh king and daughter of the earl of Chester) may have been a contributory cause of his subsequent difficulties with the Normans as some sources say he was already promised to the daughter of William, Duke of Normandy:

- Harold had been married before, but the name of his first wife is unknown. On her death, he had contracted to marry Adeliza, one of the daughters of William the Conqueror, who had aimed thus to unite his family to one whom Edward, who was childless, designed as his successor. Harold, when he married Editha, and broke through his promise to William, did it in the hope of strengthening his interest at home; for by this match he bound the two powerful Earls, Edwin and Morcar, the brothers of Editha, and with them the English, their adherents, to espouse his cause, and from this time the son of Godwin openly aspired to the succession. - from WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR AND THE RULE OF THE NORMANS by Frank M. Stenton

One major problem with Stenton's version is that many sources do not list an Adeliza among the daughters of William. The nearest is the high-spirited and educated Adela but she was far too young (born after 1062) and she went on to have daughter (Lucia-Mahaut Countess of Chester) who was drowned in the wreck of the White Ship alongside Richard, earl of Chester. Another of Adela's contributions to history was that she was the mother of the future King Stephen. However other sources (including correspondence with Anselm of Bec - later to found the Benedictine Abbey at Chester) indicate that there was a daughter Adeliza who became a nun. The continuator of William of Jumièges states that "Adelidis", a daughter of William I, was betrothed to (King) Harold, and remained single after his death. William of Malmesbury mentions that one of William's daughters was betrothed to Harold, but dead in 1066 (Gest. Reg. lib. iii. c. 238). Planché asserts (without authority) that Adeliza was born in 1055, betrothed to Harold in 1062 (aged 7), and dead by 1066. Some sources name the daughter betrothed to Harold as Agatha (who some sources have being born in 1064). Orderic Vitalis (573 c.) states that Agatha took the veil, but other sources have her being betrothed to Alphonso of Castile and dying before the marriage could take place, reportedly out of mortification at the prospect of marriage to Alfonso). Finally Orderic seems to suggest that the who story of the betrothal was made up by Harold when returning to Edward the Confessor from Normandy:

- ... but then added falsely that William of Normandy had given him his daughter to wife and granted him as his son-in-law all his rights in the English kingdom. Though the sick monarch was amazed, nevertheless he believed the story and gave his approval to the cunning tyrant's wishes."

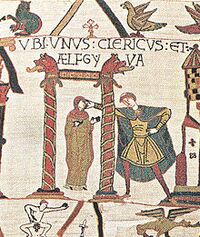

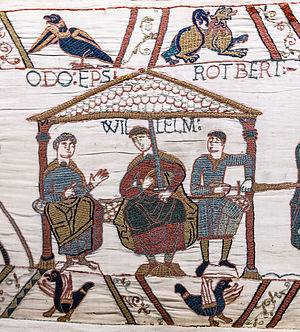

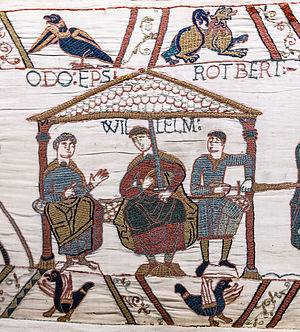

A related tale is that Harold’s sister Ælfgifu of Wessex was promised to a senior Norman baron, and that this also fell through - or that Harold was betrothed to a daughter of William called Ælfgifu (there is no evidence that he ever had such a daughter). There is a mysterious reference to Ælfgifu (Aelfgyva) in the Bayeux Tapestry but who she is or why she is incorporated has never been explained. Various writers has supposed that the image in the tapestry is supposed (due to the naked figures placed in the margins) to hint at infidelity by Harold, or perhaps even to suggest that his wife Ealdgyth (Ælfgar's daughter) was not being entirely faithful while he was away.

By 1066 Chester was a prosperous town with a population of between 2,500 and 3,000, producing annual taxes of £45 (this was pounds of silver in 1066 money: see Saxon Pound) and 120 pine marten pelts, together with an additional income from the mint - see Dark Age Chester. Chester was assessed as including the townships of Handbridge, Newton by Chester, 'Lee' (Overleigh and Netherleigh), and 'Redcliff'. Already, Chester had its own laws and customs, administered by the "hundredal court", over which presided 12 doomsmen (iudices civitatis) drawn from the men of king, earl, and bishop, and liable to fines payable to the king and earl for failure to carry out their duties. The "doomsmen" have been regarded as evidence of Scandinavian influence on Chester's institutions and have been compared to the 'lawmen' (lagemen or iudices) of some boroughs in the Danelaw.

In late Anglo-Saxon Chester the earl was particularly influential, a reflection of his very powerful position in Cheshire as a whole. In contrast with those towns where he was simply allocated the normal third share of a fixed tax income, in Chester he was entitled to a variety of other revenue and was represented by an agent, a reeve (praepositus or minister) who seems to have had similar status to the king's representative. The earl's peace was protected from infringement by the same fine of 40 shillings as that of the king's reeve. The earl's reeve took a third of the forfeitures for criminal offenses, a third of the payments for evasions of the tolls, and a third of the tolls themselves. The earl also received a third of the fixed tax and his due share of the various payments made by the city's mint. The 12 doomsmen who presided over the city court were drawn from his men as well as the king's. Apart from the king's larger share of the forfeitures, tolls, and revenue, the only expression of royal superiority appears to have been his right of first pick of pine-marten pelts.

It is clear that the Anglo-Saxon earls of Chester already enjoyed many of the benefits of a "county palatine". It is possible that the complex politics of the power balance between Mercia and Wessex had led to arrangements by which the "Count of Chester" enjoyed considerable autonomy from Winchester. Harold II had perhaps tried to simplify matters with a dynastic marriage, but Chester and the struggle for the crown were not to be separated.

1066 and all that

Edward the Confessor died childless on or about the 4th January 1066. England was up for grabs and there were several potential claimants:

- Harald Hardrada (King of Norway), could claim the English throne based on a supposed agreement between the previous King of Norway, Magnus I of Norway, and Harthacanute, whereby if either died without heir, the other would inherit both England and Norway.

- William (Duke of Normandy) had blood ties to Aethelred through Aethelred's wife Emma - but really just wanted to be King.

- Harold Godwinson (Earl of Wessex) who had been elected king by the Witenagemot of England and was on his home turf.

In spring 1066 Harold's exiled brother Tostig raided south-eastern England but his fleet was driven off. King Harald of Norway invaded northern England in early September, leading a fleet of over 300 ships further augmented by the forces of Tostig, who threw his support behind Harald's bid for the throne. Advancing on York, the Norwegians were met on 12 September by a northern English army under Edwin (earl of Chester) and Morcar (his brother), but defeated them at the Battle of Fulford and occupied York. Harold had spent the summer on the Isle of Wight waiting for William to invade, but on 8 September he had finally been forced by the exhaustion of his food supplies to dismiss his troops. He now rushed north, gathering forces as he went and took the Norwegians by surprise, defeating them in the exceptionally bloody Battle of Stamford Bridge on 25 September. King Harald of Norway and Tostig were killed and the Norwegians suffered such horrific losses that only 24 ships (of 300) were required to carry away the survivors. The victory came at great cost, as the Anglo-Saxon army was left in a battered and weakened state. How different history would have been, had a little more foresight ensured that the invaders were met by Mac Bethad mac Findlaích (just nine year's dead) under treaty with Harold.

As it was, William landed at Pevensey in Sussex on 28 September and assembled a prefabricated wooden castle near Hastings as a base. Harold rushed south at the news of William's landing and paused at London to gather more troops, then advanced to meet William. They fought at the Battle of Hastings on 14 October. It was a close battle but in the final hours Harold was killed, along with his brothers Earl Gyrth and Earl Leofwine, and the English army fled.

Following Harold's death at the Battle of Hastings against the invading Normans in October, the Witanagemot assembled in London and elected Edgar the Ætheling King. The new regime thus established was dominated by the most powerful surviving members of the English ruling class, Stigand, Archbishop of Canterbury, Ealdred, Archbishop of York, and the brothers Edwin, Earl of Mercia, and Morcar, Earl of Northumbria. Interstingly before Morcar and his brother arrived at London, sent their sister Aldgyth, Harold's widow, to Chester, and urged the citizens to raise one or other of them to the throne.

In 1067 two Norman Earls in the Welsh Marches, used the confusion caused by William's invasion, to extend their lands at the expense of English neighbours among whom were one Edric, soon to become known as 'Eadric the Wild'. In revenge for raids on his land Edric, in alliance with two Welsh princes, Bleddyn and Rhiwallon, devastated Herefordshire and eventually (1067) sacked the city of Hereford itself, before retreating back into the hills. Then, in 1069, the late King Harold's sons, who were based in Ireland, raided the west country for a second time. Unfortunately for them they met defeat at the hands of Earl Brian of Penthievre, and fled back to Ireland. At the same time Edric the Wild and his Welsh allies burst out from their fastness in the hills and took Shrewsbury before moving on to Chester. William had to leave them to their own devices as he had his hand's full dealing with an uprising in Northumberland lead by the English Earl of Northumberland Morcar and his brother Earl Edwin of Mercia, supported by the Danish king, Swein Esthrithson, who also had a claim to the English throne.

- The Conqueror had now only to gather in what was still left to conquer. But, as military exploits, none are more memorable than the winter marches which put William into full possession of England. The lands beyond Tees still held out; in January 1070 he set forth to subdue them. The Earls Waltheof and Gospatric made their submission, Waltheof in person, Gospatric by proxy. William restored both of them to their earldoms, and received Waltheof to his highest favour, giving him his niece Judith in marriage. But he systematically wasted the land, as he had wasted Yorkshire. He then returned to York, and thence set forth to subdue the last city and shire that held out. A fearful march led him to the one remaining fragment of free England, the unconquered land of Chester. We know not how Chester fell; but the land was not won without fighting, and a frightful harrying was the punishment. In all this we see a distinct stage of moral downfall in the character of the Conqueror. Yet it is thoroughly characteristic. All is calm, deliberate, politic. William will have no more revolts, and he will at any cost make the land incapable of revolt. Yet, as ever, there is no blood shed save in battle. If men died of hunger, that was not William’s doing; nay, charitable people like Abbot Æthelwig of Evesham might do what they could to help the sufferers. But the lawful king, kept so long out of his kingdom, would, at whatever price, be king over the whole land. And the great harrying of the northern shires was the price paid for William’s kingship over them. - E. A. Freeman William the Conqueror

Identified as a centre of disaffection and potential further revolt, Chester was dealt with severely. In 1071 Edwin, Earl of Mercia again sought to rebel but Edwin was soon betrayed to the Normans by his own retinue and killed (Morcar joined the insurgents in the Isle of Ely - Bishop Aethelwine of Durham and Hereward the Wake, and remained with them until the surrender of the island later that year. Morcar, it is said, surrendered himself on the assurance that the king would pardon him and receive him as a loyal friend. William, however, committed him to the custody of Roger de Beaumont, who kept him closely imprisoned in Normandy). By 1071, the value of recoverable taxes had reduced from £45 to £30 (of silver) and Chester was described as 'greatly wasted'. Of 487 houses standing in 1066, 205 had been lost and were perhaps not rebuilt before 1086. The increase in the taxation of the city under Earl Hugh to £70 and a mark of gold (about its pre-conquest level) may indicate more burdensome exactions rather than returning prosperity.

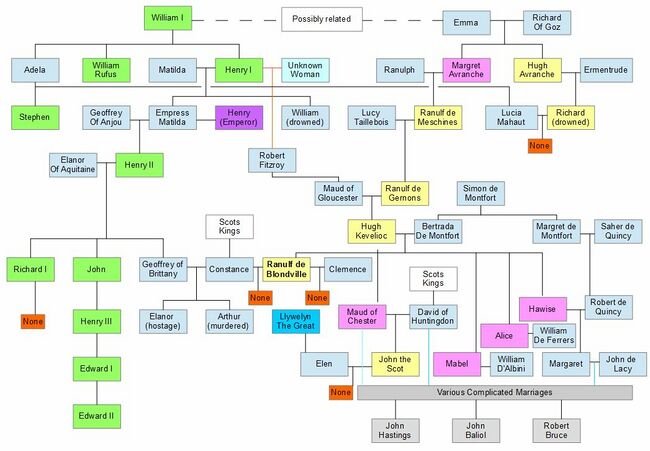

The Norman Earls

So came the Normans. The Norman Earls of Chester Hugh of Avranches, Richard of Avranches, Ranulf de Meschines, Ranulph De Gernon, Hugh de Kevelioc, Ranulf de Blondeville and John Canmore span the period from the Norman Conquest of 1066 to the first parliament under Henry III (1 October 1207 – 16 November 1272). Given that the number of invading Normans was relatively small (estimates suggest about 5000 knights) and the English population was over two hundred times larger (estimates place it around 1,100,000), the Norman aristocracy was characterized by complex intermarriage within quite a small gene pool. The early part of Norman rule was also characterized by significant manoeuvrings for position and the formation of power alliances that backed either the right side or the wrong one. The complex successions can be followed in part on the English Monarchs family tree, but in reality it was even more complex.

A Gallery of the Norman Earls

As well as owning land in England, the Earls also had extensive holdings in Normandy, especially in the Contentin Peninsula.

William I created the "Honor of Chester" from the landed estates of dozens of pre-Conquest owners. Firstly, there were the lands of Earl Edwin of Mercia, the minster church of St Werburgh and all the lesser theigns and freemen that formed a neat package defined by the county boundary. This concentration of ownership within a single county was unique in Domesday's time and the only other lords which came close were Roger of Montgomery (Shropshire) and Williams half-brother Robert of Mortain (Cornwall), but even these two had to co-exist with other French lords within their county. Outside of Cheshire:

- the largest part of the lands granted to the first earl comprised estates taken from the Anglo-Saxon magnates - Harold, Tostig and Siward, Archbishow Stigand of Cantebury, Eadgifu (Harold's wife) and Edgar the Atheling;

- a second group of lands were previously held by Harolds more important theigns and officials including Harolds chamberlain Hugh, steward Eadnoth and the senior housecarl Burgheard of Mendlesham.

- a third and smallest group came from other leading supporters of Harold.

Two reasons are normally given for William creating such a powerful position as the Earldom of Chester:

- First, he is seeking to reward Hugh, then the young and capable heir to major holdings in Normandy for his assistance during the conquest.

- Second, he is seeking to defend the northern part of the Welsh border and place a powerful ally in a strategic location with a major port.

But that doesn't explain why William gave, outside of Cheshire, the greater part of Harold's lands and the lands of his closest supporters to the earl of Chester, rather than giving him the lands of others. Possible explanations are that William feared uprisings in those lands, or that he wished to create a large and stable power-block in case his own sons proved incapable of running the country. Perhaps the most likely explanation is that:

- The land of various dukes/counts had, since before the Norman Conquest been somewhat scattered. This had the practical benefit that a border land-holder, if attacked, would have resources to draw on elsewhere, away from the border. It also meant that if the land-holder revolted, he would find it difficult to defend all his lands against the king, and,

- There was no central "land registry" from which an apportionment of land could be made, and this would have been a complex process. As William did not recognise that Harold II had ever been a valid king of England. It would have been simpler for William to simply say "you can have the lands of N---". Indeed when the Domesday Book was being compiled after 1085, land-holdings were in-part based on holdings (1) at the time of Edward the Confessor's death, (2) when the new owners received it, and, (3) at the time of the survey.

Another theory is that Hugh of Avranches was a close relative of William. A manuscript relating to St Werburgh´s Chester records that “Hugo Lupus filius ducis Britanniæ et nepos Gulielmi magni ex sorore” (Hugh Lupus son of the duke of Britanny and nephew of William the Great through his sister) transformed the foundation into a monastery. This suggests that Hugh's mother was a daughter of Herluin de Conteville (William was supposedly the product of an affair between Robert I, duke of Normandy, and a woman called Herleva (the daughter of a tanner). According to Oderic Vitalis Hugh of Avranches's parents were Richard "le Goz" Vicomte d'Avranches and his wife Emma [de Conteville]. However no other indication has been found that Emma was a de Conteville. Herleva was married off to Herluin de Conteville and gave birth to Odo or Eudes, who became Bishop of Bayeux, and Robert who became Count of Mortain; both were prominent in the reign of their half-brother William. As Wlliam was born around 1027 and Herleva later married Herluin de Conteville in 1031, Emma must have been born after that. Hugh of Avranches was said to have been born around 1047, which would mean that his mother (if she was Emma) was not more than about 16 when he was born.

Another reason why the "close" relative reason might be discounted is that Hugh of Avranches was not even the first Earl, but that appears to have been Gherbod the Fleming, whose eventual fate was somewhat mysterious.

A direct consequence of the Norman invasion of 1066 was the near total elimination of the Anglo-Saxon aristocracy, and the loss of English control over the institutions of state such as the Church. By the time of the Domesday Book (1086), only two English landowners of any note had survived. By 1096 no church See or Bishopric was held by any native Englishman - all were held by Normans. The Normans also established regular monasticism within the city. In 1092 Anselm, then abbot of Bec, visited Chester at Hugh of Avranches invitation to refound the minster of St. Werburgh's as a community of Benedictine monks. The new monastery received large endowments from Hugh of Avranches and his principal tenants, and from the beginning was clearly intended as their pantheon. Hugh of Avranches's cousin and leading baron, Robert of Rhuddlan, was initially buried in the abbey in 1093 or 1094, before his removal to SaintEvroul (Orne), and all the Norman earls except Richard, drowned in the White Ship, were also (at least in part) interred there.

No other medieval European conquest of Christians by Christians had such devastating consequences for the defeated ruling class (indeed, many Anglo-Saxon nobles and soldiers ultimately found Norman domination unbearable, and emigrated to Byzantium, placing themselves at the service of the Byzantine Emperor. Anglo-Saxon emigres came to dominate an elite unit called the Varangian Guard, which served as the Byzantine Emperor's own bodyguard and continued in existence until at least 1204. By the 12th century, the Varangian Guard contained so many Saxons that the entire unit was sometimes called "the English Guard"!).

The Norman Earls

FLEMING

- Gherbod the Fleming(1070-1071) - either dies in a dungeon or becomes a monk

AVRANCHES (first creation)

- Hugh of Avranches: 1st Earl of Chester, created (1070-1101) - eventually becomes a monk, then dies.

- Richard of Avranches: 2nd Earl of Chester (1101-1120) - drowns on the wreck of the "White Ship" - no children.

MESCHINES (second creation)

- Ranulf de Meschines: 1st Earl of Chester (1120-1129) - a brief earldom and death by natural causes.

- Ranulph De Gernon: 2nd Earl of Chester (1129-1153) - a serial turncoat, may have eventually been poisoned.

- Hugh de Kevelioc: 3rd Earl of Chester (1153-1181) - revolted, imprisoned, released, restored.

- Ranulf de Blondeville: 4th Earl of Chester (1181-1232) - dies without issue although his adopted son was declared heir to the English throne.

CANMORE (third creation)

- John Canmore: known as "John the Scot" Earl of Chester (1232-1237) - dies without issue.

Complex Successions

Later in life, William the Conqueror put on weight. In 1087 William was told that King Philip of France described him as looking like a pregnant woman. William mounted a furious attack on Philip's territory, and on 15th August captured Mantes and set fire to it. As the town burned, William was thrown against the pommel of his saddle so violently that "his intestines burst". He lingered for five weeks, but on September 9, 1087 died. When the king was on his deathbed in 1087, he ordered that Morcar should be released, in common with others whom he had kept in prison in England and Normandy, on condition that they took an oath not to disturb the peace in either land. Morcar was not long out of prison, for William Rufus took him to England with him, and on arriving at Winchester put him in prison there. Nothing further is known about Morcar and it is therefore probable that he died in prison.

Returning to William, events then descend to farce - William's servants strip him bare and abandon his body, leaving it to a kind-hearted knight to arrange a funeral at the abbey of St. Stephen in Caen. The funeral is however disrupted by the outbreak of a fire and the original owner of the land on which the church was built claims he had not been paid yet, demanding 60 shillings. After extinguishing the fire (and after paying-off the landowner), the pallbearers try to cram William's bloated corpse into a too-small sarcophagus and the body explodes, creating a horrible smell that sends everyone running for the exits (this is not the end of Williams troubles as his bones were later scattered and now only his femur remains). Meanwhile, his sons were already squabbling over the kingdom.

Succession was seldom straightforward for the Anglo-Norman kings, William the Conqueror's eldest son Robert Curthose (his name means "Bobby Short-Pants"), never ruled England and political manoeuvring meant that William was succeeded (in 1087) by his second son (William Rufus). In 1092, at the (third) invitation of Hugh of Avranches, Earl of Chester, Anselm of Bec crossed to England to found the Benedictine Abbey at Chester and was detained there by business for nearly four months. Alselm had spent some time in Avranches in 1060 before entering the abbey of Bec as a novice - and it is possible that he met Hugh of Avranches then. When about to return to Bec, he was refused permission by Rufus however the following year, when the king fell ill (and believed himself dying) he nominated Anselm to the then vacant see of Canterbury. The reluctant Anselm was finally consecrated as Archbishop of Canterbury in 1093. This was a disaster for William as the two did not get on. In 1097 Anselem had decided to escape conflict with William and sailed from Dover to France leaving the estates of Canterbury in the King's hands. As history was written down by scholars who tended to be churchmen (and hated William) he is usually recorded as "an effeminate and low morals". William Rufus was shot with an arrow during a hunting expedition in 1100. There's an inscription on the 'Rufus Stone' near the village of Minstead, in the New Forest, which reads:

- 'Here stood the oak tree on which an arrow shot by Sir Walter Tyrrell at a stag glanced and struck King William II surnamed Rufus on the breast of which storke he instantly died on the second day of August anno 1100. King William thus slain was laid on a cart belonging to one Purkess and drawn from hence to Winchester, and buried in the Cathedral Church of that City'.

Following William's "accidental" death William's third son (who was in the same area when the accident happened) seized the conveniently close royal treasure, arranged a speedy coronation and became Henry I. The Earls of Chester, Hugh of Avranches and Richard of Avranches were closely involved with and intermarried into the ongoing dynastic soap. But, their's and almost everyone else's plans were thrown into confusion with the loss of the "white ship" in 1120 and the death by drowning of both earl Richard of Avranches and the heir to the English throne. Leaving (on Henry I's death from a "surfeit of lampreys") a contested succession between Henry I's daughter Matilda and William I's maternal grandson Stephen. Before Henry's death came the brief earldom of Ranulf de Meschines (1120-1129) who was a supporter of Henry against various revolting nobles.

Henry wanted Matilda to succeed him, but England was not ready for a female monarch and civil war followed the death of Henry I. The then Earl of Chester (Ranulph De Gernon) took and changed sides until the coronation of Matilda's son, the first of the Plantagenet (Angevin) kings, Henry II, in 1154. However, while Stephen's reign was mostly an utterly chaotic civil war, he did manage to die a natural death. The same cannot be said for Ranulph De Gernon who was supposedly poisoned.

The next Earl Hugh de Kevelioc joined the 1173 revolt by some of Henry II's sons (Henry, Richard, Geoffrey and John) against their father the king and briefly lost his lands as a consequence. Weak, ill, and deserted by all but an illegitimate son, Geoffrey, Archbishop of York, Henry II died at Chinon on 6 July 1189. His legitimate children, chroniclers record him saying, were "the real bastards."

The following Earl, (Ranulf de Blondeville) briefly broke with the long-standing family tradition of invading Wales and made an alliance with Llywelyn the Great (effectively Prince of Wales), whose daughter Elen married Ranulf de Blondeville's nephew and heir, John Canmore John of Scotland or John de Scotia, in about 1222. Ranulf de Blondeville served Henry II (died miserable), Richard (died of a festering wound), John (died of dysentery after loss of his crown jewels) and Henry III (went senile) more or less faithfully, and himself died (1232) without offspring.

John the Scot (John Canmore) inherited in 1232 but died childless in 1237. After his death, the "honour of Chester" was bought from Ranulph's sisters by Henry III, who gave it to his son Edward (17 June 1239 – 7 July 1307) - later to become Edward I.

The Earls and Chester

It is not clear how often the Norman earls actually stayed or lived in Chester. Their presence was recorded at special occasions:

- Hugh I's attendance at the ceremonies marking the establishment of St. Werburgh's abbey in 1092,

- A gathering of leading Angevin supporters convened in Chester by Ranulph II in 1147-8, which included his nephew Earl Gilbert of Clare, Earl Roger of Hereford, Cadwaladr ap Gruffudd, younger brother of the ruler of Gwynedd, and William FitzAlan of Oswestry (Salop.),

- Ranulph III's visits to meet Llywelyn ap Iorwerth in 1220 and 1231,

- In 1224, when the disgraced Fawkes de Breauté fled to Chester and Ranulph III wrote to Henry III in his defence).

However it should be remembered that the Norman King's policy was to grant relatively small parcels of land throughout the country (including Normandy), so that if a Baron revolted he would only be able to defend part of his lands at a time.

The earls are remembered with:

- their shields on the Queen's Park Suspension Bridge over the river Dee,

- their shields and carvings on the above the ground floor on the front face of the Grosvenor Park Lodge (designed by John Douglas), inside the entrance to Grosvenor Park.

- stained glass depictions on the staircase of the Town Hall. Further images of which can be found here.

- some carvings in the porch of the Town Hall and about the building

- a series of eight late 16th century painted boards in the Town Hall depicting the Norman earls and Edric Sylvestris (Eadric the wild), supposed ancestor of the Sylvesters of Storeton in Wirral. Formerly in the possession of the Stanleys of Hooton, they were purchased by Sir Thomas Gibbons Frost and presented by him to the city during his mayoralty in 1883.

- various other works of sculpture around Chester.

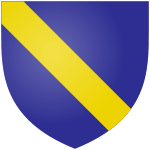

The arms of the earls are shown on the right, they are described in Cheshire Antiquites (Strutt, 1838) as:

AVRANCHES (first creation)

- Hugh of Avranches: 1st Earl of Chester, created (1070-1101) - "Azure, a wolf's head argent" (silver wolf's head on blue)

- Richard of Avranches: 2nd Earl of Chester (1101-1120) - "Crusilly, a wolfs head" (wolf's head with crosses)

MESCHINES (second creation)

- Ranulf de Meschines: 1st Earl of Chester (1120-1129) - "Or, a lion rampant gules" (red lion on gold)

- Ranulph De Gernon: 2nd Earl of Chester (1129-1153) - "Gules, a lion rampant argent" (gold lion on red)

- Hugh de Kevelioc: 3rd Earl of Chester (1153-1181) - "Azure, six garbs or" (six gold sheaves on blue)

- Ranulf de Blondeville: 4th Earl of Chester (1181-1232) - "Azure, three garbs or" (three gold sheaves on blue)

CANMORE (third creation)

- John Canmore: known as "John the Scot" Earl of Chester (1232-1237) - "Or, three piles gules" (three red wedges on gold)

Another set of stained glass panels of the Earls can be found in Warwickshire. This glass of the third quarter of the 16thC was originally made for Brereton Hall, Brereton Green, in Cheshire. The glass was sold at auction in Liverpool in 1818 and bought by Abraham Bracebridge, who installed it in his library at Atherstone Hall, Warks. On his death he bequeathed the glass to his friend Lord Leigh of Stoneleigh Abbey, Warks, where it remains today.

There is a variation between Ranulf de Gernon's coat of arms as shown on the Queens Park bridge and elsewhere. A church window shows a metallic lion on a red field, while the bridge shows the opposite. To add further confusion Ranulf de Meschines (de Gernon's father) has arms which are, on the bridge a white lion on a red ground and in the stained glass of the town hall possibly a red lion on some other colour (possibly gold) ground. Could it be that one or the other has got the arms of the father and son mixed up or is this some subtle pun on "turn-coat" (as both father and son revolted against their kings)? The arms on the lodge in Grosvenor Park also show that the father and son had oppositely coloured arms (it seems like the garden-gnome like statues are in the right order) but in this case they have become blue and gold!

The Braun and Hogenberg map of Chester (from around 1581) shows "ruins of the house of the count of Chester" by the River Dee in Edgar's Field (also known as "Kettle's Croft" prior to 1892), close to the present day location of The Ship Inn. The area below the weir and around the Old Dee Bridge is now known as the "King's Pool". However, before the earldom of Chester passed to the Crown in 1237 it was called the Earl's Pool. A fishery developed at this location because since (prior to the construction of the salmon steps) fish could only pass over the weir at high tide - all fishing in the Dee at Chester was under the control of the Earl.

The Palace of the Earl

Both the Braun and Hogenberg map of Chester (from around 1581) and later maps shows "ruin of the house of the count of Chester" by the River Dee in Edgar's Field (also known as "Kettle's Croft" prior to 1892), close to the location of Minerva Shrine. In 973, the Anglo Saxon Chronicle records that, two years after his coronation at Bath, King Edgar of England, came to Chester where (according to Florence of Worcester - writing around 1100) he held his court in a palace, which tradition holds was in a place now known as Edgar’s field near the old Dee bridge in Handbridge:

- "On a certain day they [the "eight petty kings"] attended him [Edgar] in a boat, and when he had placed them at the oars, he himself took the helm and skilfully steered it down the river Dee, and thus, followed by the whole company of earls and nobles, in this order went from the palace to the monastery of St.John the Baptist. After having prayed there, he returned with the same pomp to the palace."

Of course there was no weir at that time, so Edgar would not face the problems that would occur in repeating the journey today.

It is curious that there should be two palaces associated with the same spot, and it seems odd that the Earl should have his palace located outside of the walls of the city. Edgar's Field was laid out as a public park (and renamed from "Kettle's Croft") by the first Duke of Westminster, Hugh Lupus Grosvenor who presented it to the City of Chester in 1892 as one of the family's many philanthropic activities.

The area below the weir and around the Old Dee Bridge is now known as the "King's Pool". However, before the earldom of Chester passed to the Crown in 1237 it was called the Earl's Pool. A fishery developed at this location because since (prior to the construction of the salmon steps) fish could only pass over the weir at high tide - all fishing in the Dee at Chester was under the control of the Earl.

The Coming of the Royal Earls

If John Canmore had a son, that son (whose mother would have been Elen ferch Llywelyn, daughter of Llywelyn the Great), or possibly a grandson, that child would have had a legitimate claim to the throne of Scotland as well as the Earldom of Chester - and very good Welsh connections. Had the Earldom of Chester continued in this manner, Edward I would have faced serious problems in both his attempts to conquer Wales and his wars with Scotland.

However, since the death of John Canmore the Earldom has (mostly) stayed with the Royals. It was briefly promoted to a principality in 1398 by King Richard II, but was reduced to an Earldom again in 1399 by King Henry IV. The Sovereign's eldest son is born Duke of Cornwall but must be made or created Earl of Chester (and Prince of Wales; see the Prince Henry's Charter Case (1611) 1 Bulst 133; 80 ER 827). Prince Charles was created Earl of Chester on 26th July 1958 (when he was also made Prince of Wales and Earl of Carrick) and before he became King was the longest to hold the Earldom (64 years). Of the 27 English kings since Edward III, 12 had not previously been Earl of Chester. And, of the Earls of Chester since Edward III, 12 did not (or have not) yet become king.

Henry III (king from 1216 - 1272) was influenced by the religious cult of the Anglo-Saxon saint, king Edward the Confessor (who had been canonised in 1161). Henry followed his lead, took to wearing only the simplest of robes and had a mural of the saint painted in his bedchamber for inspiration before and after sleep. He even named his eldest son Edward, although Edward I was to become Lord of Chester and one of the least saintly English Kings. Henry III's reign was marked by civil strife as the English barons, led by Simon de Montfort, demanded more say in the running of the kingdom. De Montfort became leader of those who wanted the king to surrender more power to the baronial council. In 1258, seven leading barons forced Henry to agree to the Provisions of Oxford, which effectively abolished the absolutist Anglo-Norman monarchy, giving power to a council of fifteen barons to deal with the business of government and providing for a thrice-yearly meeting of parliament to monitor their performance. Henry obtained a papal bull in 1262 exempting him from his oath and both sides began to raise armies. The Royalists were led by Prince Edward, Lord of Chester and Henry's eldest son. Civil war, known as the Second Barons' War, followed - at the Battle of Lewes on 14 May 1264, Henry was defeated and taken prisoner by de Montfort's army. Henry was reduced to being a figurehead king under house arrest. In 1264, de Montfort became earl of Chester a title that became forfeit with his death, at the battle of Evesham, 1265.

The next male heir to the throne to live beyond early childhood was Alphonso (24 November 1273 – 19 August 1284) ninth child of Edward I and Eleanor of Castile. While he may have become Earl (there is no hard evidence) the next certain Earl was Edward II, nowadays remembered for his murder with a red-hot poker.

PLANTAGENET

- Edmund Crouchback Earl of Chester (1253-1254) - questionable

- Edward Plantaganet (Edward I) Lord (but not earl) of Chester (1254-1264)

DE MONTFORT (fourth creation)

- Simon de Montfort Earl of Chester and Earl of Leicester (1264-1265) - dies in battle.

PLANTAGENET (restored)

- Edward Plantagenet (Edward I), Lord of Chester (1265-1272) - he was buried in a lead casket wishing to be moved to the usual regal gold casket only when Scotland was fully conquered and part of the Kingdom of England (he is still in the lead box).

- Alphonso Plantagenet Earl of Chester (1284) - questionable, died aged 10

- Edward Plantagenet (Edward of Caernarfon, later Edward II) Earl of Chester and Prince of Wales (1301-1312) - either died of a hot poker or escaped - thereafter the title went mostly with the Principality of Wales

- Edward Plantagenet (Edward of Windsor, later Edward III) Earl of Chester (1312-1333)

- Edward Plantagenet (Edward of Woodstock, later The Black Prince) (1333-1376)

- Richard Plantaganet (Richard II) Earl of Chester (he was briefly imprisoned at Chester Castle) and Prince of Wales (1376-1399) - died without issue, possibly murdered.

The Principality of Wales and Earldom of Chester must be created, and are not automatically acquired like the Duchy of Cornwall, which is the Heir Apparent's title in England, and the Dukedom of Rothesay, Earldom of Carrick, and High Stewardship of Scotland, which are the Heir Apparent's titles in Scotland. The dignities are not hereditary, but may be re-created if the Prince of Wales predeceases the King. For example, Prince Frederick, Prince of Wales predeceased King George II, so Frederick's eldest son, Prince George (the future George III), was created Prince of Wales.

Edmund Crouchback

(Kings: Henry III) (his father)

Edmund Plantagenet (Edmund Crouchback) was born in London in 1245 (and, in case anyone is interested, died June 5, 1296). He was a younger brother of Edward I of England, Margaret of England, and Beatrice of England, and an older brother of Katherine of England. In 1253 he was invested by Pope Innocent IV in the Kingdom of Sicily and Apulia. According to some sources, at about this time he was also made Earl of Chester. These honours were of little value as Conrad IV of Germany, the real King of Sicily, was still living and the Earldom of Chester (or the style of "Lord of Chester") was soon transferred to his elder brother Edward (the Annals of Chester record it as happening in 1253 - Et eodem anno dedit Eadwardo filio suo comitatum Cestrie Gasconiam Walliam Hiberniam et plures alias terras in Anglia). Edmund also became the wonderfully named "Count of Champagne and Brie".

The name "Edmund Crouchback" does not imply a hump, but suggests that her was entitled to wear the Crusader cross (he accompanied his elder brother Edward on the Ninth Crusade to Palestine). However, when a later duke of Lancaster deposed Richard II (briefly imprisoned at Chester Castle) he claimed the kingdom (as Henry IV) by virtue of his descent from Henry III and added a hump. Henry IV's claim rested upon the supposition that Edmund Crouchback (of Lancaster), and not Edward I (Lord of Chester), was the eldest son of Henry III. This story had gone about, even in the days of John of Gaunt, who, if we may trust the rhymer John Hardyng had got it inserted in chronicles deposited in various monasteries. Interestingly the Annals of Chester record the following:

- Natus est Edmund filius Henrici regis. Item roboria facta est a clericis. (Edmund, son of king Henry, was born. Also a robbery was committed by clerks).

According to the story, Edmunds Crouchback was really hump-backed, and set aside in favour of his younger brother Edward on account of his deformity . No chronicle, however, is known to exist which actually states that Edmund Crouchback was thus set aside; he appears to have no deformity at all and Edward was six years his senior. Hardyng's testimony is, moreover, suspicious as reflecting the prejudices of the Percys after they had turned against Henry IV. - Hardyng himself expressly says that the earl of Northumberland was the source of his information. Given this known fiddling with the records it is possible that Edmund never became Earl of Chester at all and this was just a "robbery by clerks" of his elder brother's title.

The fictional Edmund Plantagenet (who would have come along over a century later) is well known to students of alternative history, and (unfortunately) never became Earl of Chester, although his brother Harry should have been.

Edward (Hammer of the Scots) - was "Lord of Chester" (and never Earl)

(Kings: Henry III) (his father)

Henry III (king from 1216 - 1272) was influenced by the religious cult of the Anglo-Saxon saint, king Edward the Confessor (who had been canonised in 1161). Henry followed his lead, took to wearing only the simplest of robes and had a mural of the saint painted in his bedchamber for inspiration before and after sleep. He even named his eldest son Edward, although Edward I was to become Lord of Chester and one of the least saintly English Kings.

Henry III's reign was marked by civil strife as the English barons, led by Simon de Montfort, demanded more say in the running of the kingdom. De Montfort became leader of those who wanted the king to surrender more power to the baronial council. In 1258, seven leading barons forced Henry to agree to the Provisions of Oxford, which effectively abolished the absolutist Anglo-Norman monarchy, giving power to a council of fifteen barons to deal with the business of government and providing for a thrice-yearly meeting of parliament to monitor their performance. Henry obtained a papal bull in 1262 exempting him from his oath and both sides began to raise armies. The Royalists were led by Prince Edward, Lord of Chester and Henry's eldest son. Civil war, known as the Second Barons' War, followed - at the Battle of Lewes on 14 May 1264, Henry was defeated and taken prisoner by de Montfort's army. Henry was reduced to being a figurehead king under house arrest together with his son Edward, later to become Edward "Hammer of the Scots".

Simon de Montfort (First Earl - fourth creation)

(Kings: Henry III)

The de Montforts were one of the families who first came to England with William the Conqueror in 1066. In January 1238 Simon de Montfort married Eleanor of England, daughter of King John and Isabella of Angouleme and sister of Henry III. Although the marriage took place with Henry III's approval, the ceremony was performed secretly with no involvement of the great barons. Eleanor had previously been married to William Marshal, 2nd Earl of Pembroke, and (the aged 16) had sworn a vow of chastity upon his death. Despite Simon making a pilgrimage to Rome to seek papal approval for their union, Edmund Rich, Archbishop of Canterbury, condemned the new marriage. However, in February 1239 de Montfort was invested with the Earldom of Leicester. He also acted as the King's counsellor and was one of the nine godfathers of Henry's eldest son, Prince Edward (later Edward I).

Soon after Prince Edward's birth, it was discovered that Simon de Montfort owed a large sum of money to Thomas II of Savoy (uncle of Henry III's queen) and had named Henry III as security for his repayment. Henry had not been told of this and became enraged. On August 9, 1239 Henry confronted de Montfort, calling him an excommunicant and threatening to imprison him in the Tower of London. Henry is supposed to have said - "You seduced my sister, and when I discovered this, I gave her to you, against my will, to avoid scandal". Simon and Eleanor fled to France to escape Henry's anger.

Having announced his intention to go on crusade two years previously, de Montfort now raised funds and set out east in the summer of 1240. He arrived in Jerusalem by June 1241, when the citizens asked him to be their governor, but does not seem to have ever faced combat in the east. In the autumn of 1241 he left Syria and joined Henry III's campaign in Poitou. The campaign was a failure, and an exasperated de Montfort declared that Henry III ought to be locked up like Charles the Simple.

In 1248 de Montfort again planned a crusade, intending to follow Louis IX of France to Egypt, but gave up to act as governor of Duchy of Gascony. Complaints about his administration led to a formal inquiry but he was formally acquitted on the charges of oppression, but his financial accounts were disputed, and he retired in disgust to France in 1252. The nobles of France offered him the regency of the kingdom, vacant by the death of the Queen-mother Blanche of Castile, but he preferred to make his peace with Henry III which he did in 1253

At the "Mad Parliament" of Oxford (1258) de Montfort appeared side by side with the Earl of Gloucester at the head of the opposition - his name appears in the list of the fifteen councillors would would rule the country. In 1261, when Henry revoked his assent to the Provisions of Oxford, de Montfort again left the country in despair. He returned in 1263, at the invitation of the barons, who were now convinced of the king's hostility to all reform; and raised a rebellion - the Second Baron's War - with the object of restoring the form of government which the Provisions of Oxford had ordained. Though merely supported by the towns and a few of the younger barons, he triumphed by superior generalship at the Battle of Lewes (May 14, 1264) where Henry III, Prince Edward, and Richard of Cornwall fell into his hands.

In 1264, de Montfort became earl of Chester - given that the King and his son were in captivity at the time it would appear that the earldom was not given freely. The Annals of Chester record it as follows:

- Post festum Omnium Sanctorum Henricus rex Anglie et Edwardus primogenitus ejus concesserunt Simoni de Monteforti, Comiti Leycestric et heredibus suis Cestriam cum toto comitatu et castellum. Novum castellum-sub-lima. Et castellum de Peck cum omnibus honoribus et pertinentiis Jure perpetuo possidenda pro aliis terris quas Simon comes in diversis Anglie locis predicto Edwardo in excambium dedit. (After the feast of All Saints [November 1], Henry, king of England, and Edward, his eldest son, granted to Simon de Montfort, earl of Leicester, and his heirs, Chester, with the whole county and the castle, Newcastle-under-Lyme, and the Peak castle [in Derbyshire] with all their honours and appurtenances, to be held in perpetuity for other lands in different parts of England, which the aforesaid earl Simon gave in exchange to the aforesaid Edward.)

Matthew of Westminster put it as follows:

- There was but little mention made for a year of the deliverance of Edward, the king's eldest son, until he himself, as the price of his release, gave his palatine county of Chester to the aforesaid earl of Leicester, and thus he purchased his liberation from the imprisonment and custody of the knights, his enemies.

The reaction against his government was baronial rather than popular; and the Welsh Marcher Lords particularly resented Montfort's alliance with Llywelyn ap Gruffydd, Prince of Wales. Many other barons who had initially supported him now started to feel that Montfort's reforms were going too far, and his many enemies turned his triumph into disaster. In May 1265 Edward I escaped captivity and raised an army which defeated de Montfort at the Battle of Evesham. de Montfort was cut down in the battle and his body was mutilated (his head, hands, feet and testicles were cut off - but not perhaps in that order). Following this victory further savage retribution was exacted on the rebels and authority was restored to Henry III.

The Chester Annals tell the local part of the story:

- Dominus autem Eadwardus apud Herford die Jovis in Septimana Pentecostes de custodia Domini Simonis de monteforti evasit. Quo audito Jacobus de Audethlegio et V.de Sancto Petro, Sabbato sequenti castrum de Beuston nomine domini Edwardi ceperuntetdie Sancte Trinitatis Cestriam venientes de consilio civium, Lucam de Taney cum suis complicibus infra castrum Cestrie obsederunt per decem Septimanas continuas nec tamen illud obtinuerunt propter optimam inclusorum defencionem. Jacobus de Audethlegio factus est Justiciarius. Dominus vero Eadwardus interim associatis sibi Gilberto de Clare et aliis commarchionibus suis Simonem de Monte forti Henricum filium ejus Hugonem Disspenser, Petrum de Monte forti, Radulfum Basset et eorum complices sæpius [d]ebellavit et tandem eos apud Evsham ij. non. Maii (fn. 13) in bello campestri prostravit: Winfridum de Bon, Henricum de Hasting, Guydonem de Monte forti in ipso bello captos apud castrum de D.(?) Beuston secum ducendo captivos. Audiens autem Lucas de Taney dominum Edwardum apud Beston venisse ij vigilias Asumpcionis castrum Cestrie reddidit eidem se suosque gratie sue subjiciendo. (But the lord Edward escaped from the custody of Simon de Montfort at Hereford on the Thursday in Whit Week. When this was known James de Audley and Urian de Saint Pierre on the following Saturday seized the castle of Beeston in the name of the lord Edward, and coming to Chester on Trinity Sunday, they besieged Lucas de Taney and his accomplices in the castle of Chester for ten consecutive weeks, but did not succeed in taking it, on account of the excellent defence made by the besieged. James de Audley was made justiciary of Chester. In the meantime the lord Edward, Gilbert de Clare and others his fellow marchers being joined with him, made frequent attacks upon Simon de Montfort, Henry his son, Hugo Despencer, Peter de Montfort, Ralph Basset, and their accomplices, and at length completely overthrew them on the battlefield of Evesham on May 6. Humphrey de Bohun, Henry de Hastings, and Guy de Montfort, who were captured in this battle, Edward took with him as prisoners to Beeston castle. When Lucas de Taney heard that the lord Edward had come to Beeston, he surrendered the castle of Chester on the day before the eve of the Assumption, submitting himself and his companions to Edward's grace.)

Sources and Links

- Audleys - Henry de Aldithley, Sheriff of Shropshire and Staffordshire, b abt 1172, of Heleigh, Staffordshire, England, d sh bef Nov 1246. He md Bertrade de Mainwaring 1217, daughter of Sir Ralph de Mainwaring, Seneschal of Chester, and Amicia le Meschin. She was b abt 1198, d aft 1249.

Alphonso (Earl of Chester?)

(Kings: Edward I)

The next male heir to the throne to live beyond early childhood was Alphonso (24 November 1273 – 19 August 1284) ninth child of Edward I and Eleanor of Castile. The other contenders would have been:

- John, born at either Windsor or Kenilworth Castle June or 10 July 1266, died 1 August or 3 1271 at Wallingford, in the custody of his great uncle, Richard, Earl of Cornwall.

- Henry, born on 13 July 1268 at Windsor Castle, died 14 October 1274 either at Merton, Surrey, or at Guildford Castle.

While Alphonso may have become Earl there is no hard evidence. Indeed his death is mentioned in the Annals of Chester but not as Earl:

- Eodem anno die Sabbati post festum Assumptionis beate Marie virginis xvj kal. Septembris mortuus est Dominus Alfonsus filius regis E pro cujus morte publice est dolendum per totam Angliam et pro vita Regis Edwardi supplicandum. (In the same year on the Saturday after the feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary on August 17, died the lord Alfonso, son of king Edward, on account of whose death there had to be a public mourning through the whole of England, and prayers had to be made for the life of king Edward.)

Edward (Of hot poker fame)

(Kings: Edward I)

The next certain Earl was Edward II, nowadays mostly remembered for his murder with a red-hot poker (whether that actually happened or not has been the subject of much discussion), although there are those who try to salvage his reputation. Edward was the fourteenth child of Edward I and Eleanor of Castile. The inscription on a sculpture at the Town Hall reads "Edward Prince of Wales Receiving Homage: First Royal Earl Of Chester AD 1254". This presents something of a problem: King Henry III passed the Lordship of Chester, but not the title of Earl, to his son the Lord Edward in 1254, and as King Edward I he in turn conferred the title and the lands of the Earldom on son, Edward (later Edward II) - who was only born in 1284, and who was made the first English Prince of Wales in 1301. In 1254 the Prince of Wales was Llywelyn ap Gruffydd. He has been Prince of Wales since 1246 and would be so until 1282. David Powel, a 16th-century clergyman, suggested that the baby was offered to the Welsh as a prince "that was borne in Wales and could speake never a word of English", but there is no evidence to support this account, and Edward II was made Prince of Wales in 1301 when he would have been about 16 years old and presumably had learned to speak English.

The "Iron Yard"

Edward II may have standardised measures based on his "iron yard" (although he was not the only king to do this - the Anglo-Saxons used the "North German Foot" which was about 10% longer than the current foot). As written in the "Liber Horn" (completed by Andrew Horn in about 1311):

- "And be it remembered that the iron yard of our Lord the King containeth 3 feet and no more, and a foot ought to contain 12 inches by the right measure of this yard measured, to wit, the 36th part of this yard rightly measured maketh 1 inch neither more nor less and 5 yards and a half make a perch that is 16 feet and a half measured by the aforesaid yard of our Lord the King."

Five yards and a half make a perch (also known as a rod or pole), and 40 perches in length and 4 in breadth make an acre. In the uk the "traditional" size of an allotment is 10 poles, a pole also being an area of 5.5 by 5.5 yards, or a "square perch", giving 16 ten-pole plots per acre. The length of the chain was standardized in 1620 by Edmund Gunter at exactly four perches. Fields were measured in acres, which were one chain (four perches) by one furlong (ten chains). The word "acre" is derived from Old English æcer originally meaning "open field", cognate with west coast Norwegian "ækre", Icelandic "akur", Swedish "åker", German "Acker", Dutch "akker", Latin "ager", Sanskrit "ajr", and Greek "αγρός" (agros). Thus, Edward's measurements were based on older units: the "hide" was an English unit of land measurement originally intended to represent the amount of land sufficient to support a household. It was traditionally taken to be 120 acres. In the Danelaw (and in Handbridge) the equivalent unit was the Carucate - approximating the land a plough team of eight oxen could till in a single annual season, named for the carruca, a heavy plough that began to appear in England in the 9th century, introduced by the Viking invasions of England. The Danelaw carucates were subdivided into eighths: oxgangs or bovates based on the area a single ox could till in a year.

The rod may have originated from the lenght of a ox-goad, while the name perch probably derives from the Ancient Roman unit, the pertica (9.7 ft - ten "pedes", or Roman feet). The measure also has a relationship to the military pike (pole) of about the same size, although these varied from 10-25 feet. The furlong (meaning furrow length) was the distance a team of oxen could plough without resting (about 200 metres). Thus, the acre was also roughly the amount of land tillable by one man behind one ox in one day. Traditional acres were long and narrow due to the difficulty in turning the plough. Land in Chester itself was also divided into standard plots, known as "Burghal Plots". These would have a narrow street frontage and extend away from the street. These were 20 by 2 perches (approcimately 100 x 10 m) - making a total area of 40 square perches. The 2-perch (11-yard) width of the plots survives in the frontages of many city plots to this day. The area of these plots was also known as a rood, which is a quarter of an acre.

Ploughing of arable land was performed with a first furrow down the center furlong, then alternating furrows to either side. As the ploughshare always turned the soil to the right this would mean that a eventually one or more ridges would build up on the long axis of the plot, giving rise to the "ridge and furrow" crop-mark structures which can still be seen today. In Cheshire these are known as "butt and rean". "Rean" is from the Old English "Ryne" - used elsewhere in England as an agricultural term for a drainage ditch and possibly having the same origin (in a linguistic sense) as "Rhine".

Red hot poker or red herring?

Edward II had few of the qualities that made a successful medieval king. Edward surrounded himself with favourites (the best known being Hugh Despenser the Younger - who was awarded Chester Castle in 1322), and the barons, feeling excluded from power, rebelled. Throughout his reign, different baronial groups struggled to gain power and control the King. In 1326 came Gaveston's downfall and execution. In August of that same year, Isabella of France and Roger Mortimer invaded England with mercenary soldiers and deposed Edward. There was unrest in Chester following Edward II's deposition - in July the former mayor, Richard le Bruyn was imprisoned at the Castle accused of supporting the Earl of Mar, an "enemy and a rebel". In August the Justice was ordered to arrest the large number of outlaws who had gathered in the vicinity of the city. Isabella of France and Roger Mortimer imprisoned eighteen children in Chester Castle as hostages for the good behaviour of the townspeople in [Close Rolls 1327-1330, pp. 169, 187-188].

Ranulph Higden's Polychronicon, written in c. 1342 in Chester shows that Higden was one of the very first chroniclers who believed in the red-hot poker murder of Edward II (1327), which John Trevisa translated into English as:

- "a hoote broche putte thro the secret place posteriale."

The earliest chronicles state that Edward II died of a grief-induced illness. Those written after 1330 state that he was murdered, strangled or suffocated. Between 1332 and 1337 the chroniclers start to state that the murderers were Thomas Gurney and John Maltravers (even though John Maltravers had never been accused officially of the crime but was tried for a different one in 1330). Around 1340 chronicles start to repeat the story of a piece of metal being inserted through his anus; at first this is described as a copper rod, then an iron one, and finally an iron poker. The only contemporary account of Edward's death was the work of Adam of Murimuth who simply says that the king was suffocated by Sir Thomas Gourney and John Mautravers and dates the deed to the 22nd September. However the more colourful version, the one that everybody believes, first appeared in the set of chronicles known as The Brut and states that:

- when that night the king had gone to bed and was asleep, the traitors, against their homage and their fealty, went quietly into his chamber and laid a large table on his stomach and with other men's help pressed him down. At this he woke and in fear of his life, turned himself upside down. The tyrants, false traitors, then took a horn and put it into his fundament as deep as they could, and took a pit of burning copper, and put it through the horn into his body, and oftentimes rolled therewith his bowels, and so they killed their lord and nothing was perceived.

The "Fieschi Letter" (written to Edward III in circa 1337 by a Genoese priest at Avignon, Manuele Fieschi) has been suggested as evidence that Edward did, in fact, escape. He then supposedly crossed to the Low Countries and travelled to Italy, visiting and being sheltered by the Pope (John XXII) in Avignon on his way through France, to live out the rest of his life in monastic hermitages near Milan. In the Italian town of Cecima, (75 km from Milan), in the abbey of Sant'Alberto di Butrio, in the small closter, a sign over an empty tomb reads:

- "here is the tomb where was buried Edward II King of England, who married Isabelle of France and whose successor was Edward III, son of him".

Other Chester connections?

There is a further Chester connection with Edward II via the Dunheved brothers, Thomas Dunheved (a friar and possibly Edward's confessor) and Stephen Dunheved who made several attempts to free Edward. After an unsuccessful attempt to release Edward from Kenilworth in March 1327, the plotters vanished for a few weeks, before showed up in Chester in early June. On 8 June 1327, Richard Damory, Justice of Chester (elder brother of Edward II's former "favourite" Roger Damory) was ordered by royal mandate to arrest and imprison Stephen and Thomas Dunheved, along with William Beaumard and John Sabant, and:

- "other malefactors who have assembled within the city of Chester and parts adjacent and perpetrated homicide and other crimes, and to enquire by jury of those parts who were their accomplices, and to keep them in prison till further orders."

It was probably the presence of the Dunheved brothers in Chester that caused Isabella of France to require the taking of eighteen children as "boy hostages" in Chester Castle, in 1327.

By 27th July Thomas, Lord Berkeley is writing to the Chancellor, John de Hothum:-

- de lor venir aforceement devers le chastel de Berkel', d'avoir ravi le pere nostre seignor le roi hors de nostre garde et le dit chastel robbe felenousement encountre la pees ("They came with an armed force towards the castle of Berkeley, seized the father of our lord the King from our guard and feloniously plundered the said castle, against the peace")