Olaf II

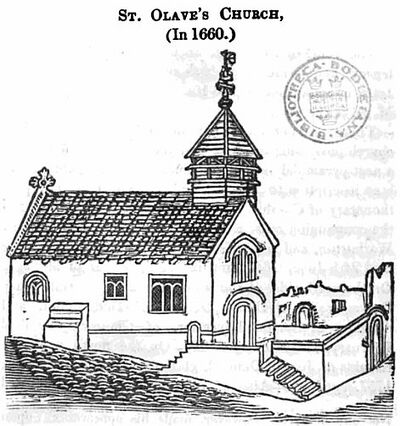

Olaf II Haraldsson (Óláfr Haraldsson c. 995 – 29 July 1030), later known as St. Olaf (and traditionally as St. Olave), was King of Norway from 1015 to 1028. Son of Harald Grenske, a petty king in Vestfold, Norway, he was posthumously given the title Rex Perpetuus Norvegiae (English: Eternal/Perpetual King of Norway) and canonised at Nidaros (Trondheim) by Bishop Grimkell, one year after his death in the Battle of Stiklestad on 29 July 1030. His remains were enshrined in Nidaros Cathedral, built over his burial site. His sainthood encouraged the widespread adoption of Christianity by Scandinavia's Vikings/Norsemen. He is the St Olave of the church in Lower Bridge Street.

The saga of Olaf Haraldsson is forever enshrined in Norwegian history as a symbol of strong national pride. Norway commemorates Saint Olaf through his symbolic axe in the national coat of arms and through Olsok Day, the July 29 holiday memorializing the battle where Olaf supposedly found martyrdom. However, modern historians mostly agree that Olaf was inclined to violence during his conquests and, in some cases, brutality against the pagan-divided kingdom.

Life

Olaf was born in Ringerike. His mother was Åsta Gudbrandsdatter, a great-great-great-great-grandchild of Ragnar Lothbrok, and his father was Harald Grenske, petty king in Vestfold, a great-great-grandchild of Harald Fairhair, Norway's first king. Harald Grenske died when Åsta Gudbrandsdatter was pregnant with Olaf. She later married Sigurd Syr, with whom she had other children, including Harald Hardrada, who later reigned as king of Norway. Hardrada is better known to the English as the person who invaded Northern England with 10,000 troops and 300 longships in September 1066, raided the coast and defeated English regional forces of Northumbria and Mercia in the Battle of Fulford near York. Although initially successful against Edwin earl of Mercia and his brother Morcar, Harald was defeated and killed in an attack by Harold Godwinson's forces in the Battle of Stamford Bridge, which wiped out almost his entire army. Modern historians have often considered Harald's death, which brought an end to his invasion, as the end of the Viking Age.

During his life Olaf was known as "Olaf the Fat" (Ólafr digri) - or "the stout". His history according to the Norwegian and Icelandic legends goes as follows:

According to tradition in about 1008, Olaf landed on the Estonian island of Saaremaa and demanded money with menaces. The locals refused to pay, so Olaf attacked them. The Osilians (the alternative term for the islanders), taken by surprise, had at first agreed to pay the "tax" he demanded but then gathered an army at the time of the negotiations and attacked the Norwegians. Olaf nevertheless won the battle. Note that this date would have Olaf making his first raids at a very early age.

In his later teens he again went to the Baltic. At this time he would have followed the traditional Norse religion, and may have been associated with the Jormsvikings an order of Viking mercenaries or brigands of the 10th century and 11th century. They were staunchly Pagan and dedicated to the worship of such deities as Odin and Thor. They reputedly would fight for any lord able to pay their substantial fees and occasionally fought alongside Christian rulers. Their stronghold Jomsborg was located on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea, but the exact location is disputed by modern historians and archeologists. Most scholars locate it on the hill Silberberg, north of the town of Wolin on Wolin island in modern-day Poland.

Viking raids on England

Some of the Jormsvikings took part in the raids which started soon after the accession of Æthelred the Unready and continued for nearly thirty years. Other Jormsvikings found it expedient to change sides and fight as mercenaries for the English. Thorkell the Tall was one prominent member of the Jomsviking order that led a great Viking army to Kent in 1009 and were promptly paid 3000 pounds of silver by the people of Kent to sway the army from attacking. They instead turned towards London and attempted to take the city several times, but were met with heavy resistance and ultimately abandoned their attack. Æthelred had gathered a fleet to oppose the Vikings but this was an utter failure: a large part of his fleet either went raiding along the south coast or was lost in storms. One theory is that the city was defended by a fortified bridge intended to prevent marine incursions up the Thames. Certainly, there is both archaeological and historical evidence for the existence of London Bridge by c. 1000. The first phase of the Saxo-Norman Bridge is known from dendrochronology to have been constructed of timber felled c. 987–1032, and it was replaced by a second bridge constructed after 1056. The existence of a Saxo-Norman London Bridge is first documented in a law code known as "IV Æthelred", which includes a section on London tolls and regulations.

Thwarted at London the Vikings returned to besiege Canterbury despite having been paid off. One account describes their excessively violent conduct and eventual murder of archbishop Ælfheah as follows:

- "Olav attacked it in 1011. One English chronicler left this description of when the city was sacked: “some of the inhabitants were run through, others burned alive in their own houses, women were dragged by their hair down the streets and burned alive; babies were crushed under heavy wagon wheels.” When the Vikings left Canterbury, they took with them not only a gigantic tribute, but also the archbishop Elfheah. During a drinking-bout the Vikings entertained themselves by throwing “stones, bones and oxen skulls” at their venerable prisoner, until one of them was deeply moved by some sort of compassion, ending the misery of man of God by splitting his head with an axe."

Pope Gregory VII canonised Ælfheah in 1078, with a feast day of 19 April. Pope Alexander III confirmed Olaf's local canonisation in 1164 with a feast day of 29 July. In the bull Non parum animus noster, in 1171 or 1172, Alexander III gave papal sanction to ongoing crusades against pagans in northern Europe, promising remission of sin for those who fought there. In doing so, he legitimized the widespread use of forced conversion as a tactic by those fighting in the Baltic.

In 1012, possibly motivated by the violence at Canterbury, Thorkell came to an arrangement with the English and his army received £48,000 in Danegeld. Thorkell remained in England afterwards with a mercenary fleet of 45 ships to defend the country against his fellow Scandinavians as a part of his arrangement with Æthelred. This was not uncommon behaviour for the Jormsvikings, who saw mercenary activity as a perfectly respectable way of life. The arrangement seems similar to the one that Æthelred had formerly made with Óláfr Tryggvasson. In 1013 Sweyn Forkbeard (another Jormsviking) invaded England. His motives were undoubtedly to extend his own domains and to check Thorkell’s power as a potential rival. Sweyn’s campaign was a brilliant success and soon the whole of southern England north of Watling Street, apart from London, had capitulated to him. Watling Street roughly follows the line from London to Chester and generally marked the southern border of the Danelaw, north of which the population contained a significan number of Scandinavian settlers and would have been disposed to the Vikings to some extent. In London Æthelred and Thorkell still held out. However, shortly before Sweyn’s death in February 1014 London capitulated to him. Æthelred was deposed and he fled to Normandy, but Thorkell’s fleet remained at Greenwich. Sweyn became the King of England on Christmas Day 1013 but he died on 3 February 1014. The Scandinavian army in England chose Sweyn’s second son Cnut as their king.

Olaf now enters the story, although he may have been a mercenary in the pay of Æthelred for some time already. The Witan asked Æthelred to return to the throne, so he returned home and Thorkell got his old employer back plus another £21,000 in Danegeld. The fact that only the people of Lindsey (North Lincolnshire) supported Cnut and that the English nobility felt able to invite Æthelred to return, implies Cnut had at that time little control over Swein’s newly conquered territories. Presumably Swein had realised that London was the key to controlling the kingdom, so he would have garrisoned it with trustworthy troops to ensure the loyalty of the city. According to the skalds Ottarr the Black and Sigvat, London Bridge and the Southwark bridgehead were strongly defended by such troops.

Æthelred's return

Æthelred needed to take the bridge at London both to allow his own troops to pass along the river and to divide the Viking forces on either side so that he could bring his forces to bear without reinforcements being able to cross between the walled City of London and Southwark. The task apparently fell to a party led by the young Olaf. In order to defend the ships against missiles tradition states that the the thatched roofs of local cottages were stolen and used to shield the ships. Olaf's attack on the bridge in 1014 involved sailing westwards upstream to the defended timber bridge, fixing ropes and grappling irons to it, then sailing downstream again and pulling down or badly damaging the superstructure of the bridge and compelling its defenders to surrender London to Æthelred’s forces.

Olaf seems to have left England after the return of Æthelred. His intention may well have been to return to Norway, where something of a power vacancy was developing. After the defeat of Olav Tryggvason at the Battle of Svolder (September 999 or 1000), Norway had been divided into a Swedish part governed by Sweyn Haakonsson and a Danish part run by Eiríkr Haakonarson. However, after Eiríkr joined his brother-in-law Cnut in his campaign to conquer England, Danish rule folded, leaving an opportunity for Olaf.

On the way home to Norway, he wintered with Duke Richard II of Normandy (23 August 963 – 28 August 1026), an ardent adherent to Christianity. Before leaving, Olaf was baptised in Rouen by Richard's brother Robert the Dane, archbishop of Normandy. Olaf returned to Norway in 1015 and declared himself king, obtaining the support of the five petty kings of the Norwegian Uplands. He had arrived with 260 men, but also a vast pile of silver and a story prepared for the church that he wished to convert the country. In 1016 at the Battle of Nesjar he defeated Sweyn Haakonsson, one of the earls of Lade and hitherto the de facto ruler of Norway. Within a few years he had won more power than any of his predecessors on the throne had enjoyed. He built churches everywhere, destroying the old heathen religious buildings and areas. Those who didn’t wish to convert to the new religion were driven in exile, forced to leave their farmland. He would chop off the arms and legs, or poke out the eyes of those who still put up a fight. Others were hung or decapitated – “none of those unwilling to serve God were spared”.

Olaf annihilated the petty kings of the South, subdued the aristocracy, asserted his suzerainty in the Orkney Islands, and conducted a successful raid on Denmark. He made peace with King Olof Skötkonung of Sweden through Þorgnýr the Lawspeaker, and was for some time engaged to Olof's daughter, Princess Ingegerd, though without Olof's approval.

In 1019 Olaf married Astrid Olofsdotter, King Olof's illegitimate daughter and the half-sister of his former fiancée. The union produced a daughter, Wulfhild, who married Ordulf, Duke of Saxony in 1042. Numerous royal, grand ducal and ducal lines are descended from Ordulf and Wulfhild.

Cnut's return

In 1016 Cnut returned to England with a large army intending to seize the English throne. Thorkell the Tall now appears to be back in the Viking camp, lending his expertise, and no-doubt his knowledge of the English military and landscape to Cnut.

Shortly after Cnut's arrival on 23 April, Æthelred died in London (aged c. 50) worn out by years of "great toil and difficulties". The succession to the English throne was disputed; the Londoners wanted Æthelred’s eldest son Edmund Ironside to rule, but others preferred Cnut. In May 1016 Cnut’s forces attempted to sail up the Thames, but they were unable to capture London Bridge and either dug a huge canal through Southwark or dragged their ships overland across north Southwark, so they could continue upstream.

The matter of the succession to the English throne was decided on 30 November 1016 by Edmund’s sudden death, which tradition ascribes to an assassin who hid in a cess-pit under a latrine until it was Edmund's turn. In 1017 Cnut partitioned England into four provinces, ruling Wessex himself and giving East Anglia to Thorkell, by way of repayment for his support.

Cnut Attacks

Cnut's brother Harald had ruled Denmark since the death of Sweyn Forkbeard. Harald II died in 1018, and Cnut went to Denmark to affirm his succession to the Danish crown. His hold on the Danish throne presumably stable, Cnut was back in England in 1020. He appointed Ulf Jarl, the husband of his sister Estrid Svendsdatter, as regent of Denmark, further entrusting him with his young son by Queen Emma, Harthacnut, whom he had made the crown prince of his kingdom. With the death of Olof Skötkonung in 1022, and the succession to the Swedish throne of his son Anund Jacob bringing Sweden into alliance with Norway, there was cause for a demonstration of Danish strength in the Baltic. Jomsborg, the legendary stronghold of the Jomsvikings was probably the target of Cnut's expedition.

Cnut now moved against Olaf. In 1025/6 Olaf lost the naval Battle of the Helgeå against Cnut, and in 1029 the discontented Norwegian nobles, supported an invasion by Cnut. Olaf had made himself unpopular by his tendency, as a zealous christian convert, to have the wives of his nobles flayed alive for sorcery. Olaf's attempts to forcibly convert people included murdering and torturing regional Jarls to terrorize them into accepting Christianity under what can only be described as a "convert or die" policy. This was actually nothing new in Norway Olaf Trygvesson (960s – 9 September 1000) King of Norway from 995 to 1000 had done much the same thing.

Olaf was driven into exile. He travelled southwards to Novgorod (Holmgard), where Olaf sought assistance from Grand Prince Yaroslav the Wise. Yaroslav, however, did not want to become directly involved in the Scandinavian power-struggles, and declined to help. Although he did offer Olaf Bulgaria if he wanted it.

In 1029, Canute's Norwegian regent, Håkon Eiriksson (who was also Earl of Worcester), was drowned when he was shipwrecked on the Pentland Firth. Olaf seized the opportunity to try to win back the kingdom or Norway. According to the official version Olaf fell in 1030 at the Battle of Stiklestad. As reported by Snorri Sturluson, Olaf received three severe wounds: in the knee, in the neck, and leaning against a large stone the final mortal spear thrust up under his mail shirt and into "his belly". Olafs younger half-brother, Harald Hardrada, was also present at the battle. Harald was only fifteen when the battle of Stiklestad took place. He became King of Norway in 1047. The authenticity of the battle as a historical event is subject to question. Contemporary sources say the king was murdered. According to the Anglo Saxon Chronicle of 1030, Olaf was killed by his own people. Adam of Bremen wrote in 1070 that Olaf was killed in an ambush, and so did Florence of Worcester in 1100. Those are the only contemporary sources that mention the death of the king. After the king's canonization it was felt that the saint could not have died in such circumstances. The story of the Battle of Stiklestad as most know it gradually developed during the two centuries following the death of King Olaf, following the argument that being a Saint, Olaf must have fallen in a major battle for Christianity.

Sainthood

The year after the battle (or assassination), Olaf's grave and coffin were opened and according to Snorri the body was incorrupt and the hair and nails had grown since he was buried. The coffin was then moved to St. Clement's Church in Trondheim. Among the bishops that Olaf had brought with him from England, was Grimketel and it was he that initiated the beatification of Olaf on 3 August. Stiklestad Church (Stiklestad kyrkje) was erected on top of the stone against which St Olaf died. The stone is supposedly still inside the altar of the church. One hundred years later, Nidaros Cathedral was built in Trondheim on the site of his original burial place. Olaf's body was moved to this church and enshrined in a silver reliquary behind the high altar. This reliquary took the form of a miniature church, common to medieval reliquaries containing the entire body of a saint, but was unique in that it is said to have had dragon heads at the apex of the gables similar to those still seen on Norwegian stave churches. In the 16th century, during the Protestant Reformation period, Olaf's body was removed from this reliquary, which was melted down for coinage by order of the Dano-Norwegian king. His remains were reburied somewhere in Nidaros Cathedral – exactly where is still today an unsolved mystery.

Aftermath

Canute, though distracted and over-stretched by the task of governing England, managed to rule Norway for five years after Stiklestad, with his son Svein and Svein's mother Ælfgifu as regents. However, the regency (due to severe rule and heavy taxation) was unpopular. Propaganda proclaiming how heroic Olaf's last stand had been made for great nation-building material in the immature Norwegian state where the warrior ethic of the Vikings and their Gods and Goddesses were still highly revered. According to Snorri, even nature lent a hand, as the day of the battle coincided with a nearly full solar eclipse, as reflected in the description of an ill-fated 'blooded red sun', which was interpreted as a certain omen of bad things to come. However, the solar eclipse took place at about 2:00 p.m. on August 31 that year contrary to the traditional date of the battle on July 29. Modern historians generally agree that Olaf was inclined to almost pyschopathic violence and brutality. Ironically he became Norway's patron saint. His canonization was performed only a year after his death by the bishop of Nidaros. The wider Catholic Church did not officially recognise him as a saint until 1164, following reports of miracles at his tomb, and, at a time when more forced conversion in Scandinavia was ongoing.

When Olaf's illegitimate son Magnus (dubbed 'the Good') laid claim to the Norwegian throne, Svein and Ælfgifu were forced (1035) to flee to England.

Five medieval London churches were dedicated to St Olave.

London Bridge is Falling Down

"London Bridge Is Falling Down" (also known as "My Fair Lady" or "London Bridge") is a traditional English nursery rhyme and singing game, which is found in different versions all over the world. It deals with the depredations of London Bridge and attempts, realistic or fanciful, to repair it. It was used by T. S. Eliot at the climax of his poem The Waste Land (1922). Some have suggested that the inspiration for the rhyme came in part from Olaf's activity during the battle for London, and is based on a poem by Óttarr svarti an 11th-century Icelandic skald. He was the court poet first of Óláfr skautkonungr of Sweden, then of Óláfr Haraldsson of Norway, the Swedish king Anund Jacob and finally of Cnut the Great of Denmark and England.

The opening lines of Ottarr’s stanza 7 has been translated, with considerable interpretation of the "kennings" (circumlocutions), as:

- Yet you broke [destroyed] the bridge[s] of London/ Stout-hearted warrior / You succeeded in conquering the land / Iron (earn) swords made headway / Strongly urged to conflict / Ancient shields were broken / Battle’s fury mounted.

Opinions are divided as to whether the poem is actually the basis for the nursery rhyme. Dredging and redevelopment near the site of the medieval bridge has produced a number of spearheads, battle axes and a grappling iron of 9th- to 11th-century date, some of which may be of Scandinavian origin. However, it has been suggested that some of the axes may have been lost by carpenters during bridge construction, not dropped in battle. The extent of the damage inflicted on the timber bridge may well have been exaggerated as Ottarr’s life apparently depended on Olaf’s approval of his composition.

St Olave Chester

St Olave's cannot have come into being before the mid 11th century, since the dedicatee, the Norwegian king Olaf II Haraldsson, was killed (at the Battle of Stiklestad) only in 1030. In 1119 the church was given by Richard the Butler to Chester Abbey together with two houses in the marketplace. Richard lived in Pulford/Poulton.

The living was a rectory in the gift of Chester abbey in the Middle Ages. It was united with St Mary on the Hill in 1394, separated in 1406, and thereafter independent until 1460 or later. Chester was well placed to take advantage of local traffic along the River Dee and, more importantly, long-distance seaborne trade. From the 10th century onwards it developed connections with Ireland and with Scandinavian settlements all round the Irish Sea. The importance which the Norse of Dublin, for example, attached to the link is apparent in their attempts to set up fortified quaysides, harbours, and navigation points along the north Welsh coast to ease the journey between the two ports. Chester almost certainly contained a sizeable Hiberno-Norse community involved in the Irish trade, located south of the legionary fortress in the quarter next to the early harbour where the clearest evidence for pre-Conquest settlement has been found.

Huts excavated in Lower Bridge Street have been interpreted as of the bow-sided type especially associated with Scandinavian sites in England. The dedications of the two churches in the area, St Bridget and St. Olave, were also appropriate for a Hiberno-Norse community. The settlement may well have extended across the river into Handbridge, which in 1086 was assessed for tax in "carucates" rather than the hides normal in Cheshire. Carucates occurred elsewhere in the county in association with Scandinavian place-names, and appear to be evidence of Scandinavian settlement.

Archaeological finds have confirmed a Hiberno-Norse presence in Chester. In particular, a brooch with Borre-Jellinge ornament found at Princess Street is identical with a brooch found in Dublin, and must have derived from the same mould.

Sources and Links

Related Pages

- St Olave: the decommissioned church in Lower Bridge Street;

- Ælfgar: the end of the Dark Ages from a Mercian perspective;

- Viking: their connection with Chester;

Links

- Olaf II: on Wikipedia;

- Olaf II: on Military Wiki;

- "Olaf the Holy";

- Fact or folklore: the Viking attack on London Bridge;

- Legends about Olaf;