Hugh de Kevelioc

Hugh de Kevelioc (1153-1181: Third Earl - revolted against the king)

(Kings: Stephen, Henry II)

Summary

Hugh of Kevelioc (born either 1141 or 1147), 3rd Earl of Chester was also known as Hugh le Meschin. He succeeded to the titles of Vicomte d'Avranches and Earl of Chester on 16 December 1153. He joined the revolt against King Henry II in 1173, was captured and deprived of his Earldom, but was then restored in January 1177. He died in 1181, leaving a young heir (Ranulf de Blondeville) aged 9.

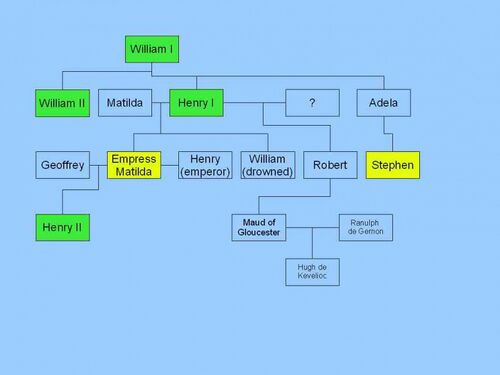

- Parents: The 2nd Earl (Ranulph De Gernon) and Maud of Gloucester, daughter of Robert, 1st Earl of Gloucester (otherwise known as Robert de Caen, the illegitimate son of Henry I of England.

- Spouse: In 1169 Hugh married Bertrade de Montfort of Evreux, daughter of Simon III de Montfort. She was the cousin of King Henry II, who gave her away in marriage.

- Children:

- Ranulf de Blondeville, (born 1172) who succeeded as the 4th Earl of Chester

- Maud of Chester (1171-1233), married David of Scotland, 8th Earl of Huntingdon as featured in Walter Scott's "The Talisman", and grandfather of Robert Bruce

- Mabel of Chester, married William d'Aubigny, 3rd Earl of Arundel

- Agnes of Chester (died November 2, 1247), married William de Ferrers, 4th Earl of Derby

- Hawise of Chester (1180-1242), married Robert II de Quincy

- A daughter, (whose name is unknown), whom some say was briefly married to Llywelyn the Great of Wales. There is some controversy here.

Hugh is also said to have had a (some claim illegitimate) daughter, Amice (Amicia) of Chester, (there is some some complicated history here) who married Ralph de Mainwaring (Justice of Chester). The Cholmondeleys of Cholmondeley "trace their ancestry to William Le Belward, Lord of a moiety of the Barony of Malpas, who married Tanglust, the natural daughter of Hugh Kevelioc" - it isn't clear which daughter is meant. A mandate from King Henry the Second to Hugh Earl of Chester and "M the Countess" enjoins them without delay to give to the Abbot and Monks of Gloucester the rents which Ranulph Earl of Chester gave them in the mills of Oldney and of Tadwell:

- H Rex Angt & Dux Norm & Aquil & Com Andeg H Com Cestf & M Comitisse sat pcipio qd sn diloe & juste faciatis hafee Abfei & Monachis de Gloec reddit q s Comes Ran eis dedit i molendinis de Oldneio & de Tadewella sic carta sua testaf Et displicet m qd hoc n fecistis sic pcepi p alia brevia mea Et n fecitis vie mei vt Justic faciat ne in clamore apli9 audia p penuria recti T Th Cane apd Wigorn

The original from which the above is transcribed is in good preservation with a fine impression of the Great Seal appended thereto a small part only having been broken off. Its date is certainly in the early part of King Henry's reign as is tested at Worcester by Thomas a Becket then Archdeacon of Canterbury the King's Chancellor. The date of the mandate is fixed somewhere between 1155 and 1163 - most probably sealed in the year 1158 when the King was at Worcester and there crowned. It is probable that the "M Comitissa" was Matilda the mother of the Earl who survived until 1189 and who might have had some interest in the Earl's lands in Oldney in right of her dower. If the Countess was not that Matilda but the wife of Hugh Earl of Chester it would supply evidence that Hugh Earl had a prior wife to Bertred - a point of considerable interest in reference to the well known controversy around the legitimacy of Amicia. The bastardy of Amicia was asserted by Sir Peter Leycester and her legitimacy maintained through a protracted pamphlet war by Sir Thomas Mainwaring of Peover. Sir Peter Leycester denied that Earl Hugh had any other wife than Bertrade, mother of Ranulf of Blundeville and of the four daughters who became coheirs of their brother.

Early Life

Hugh de Kevelioc, (1141/1147 – June 30, 1181), was the 3rd Earl of the second creation of the Earldom (and so the fifth to hold the title). He is thought (by some) to have taken his name from Kevelioc in Monmouth as his birthplace. Cyfeiliog was a small territory (cantref) in medieval Wales. The river Dyfi intersected the northwestern corner of it and formed part of its western border. Machynlleth and Tarfolwern are nearby towns. Others think that he was born in, and took the name of, Cyfeiliog in Merionethshire or Meirionydd, Wales. Hugh's arms are: "Azure, six garbs, or, three, two, and one" - this is six golden bundles of corn (garbs) arranged in rows of three two and one on a blue (Azure) background.

The Chronicle of the Abbey of St. Werburg, at Chester gives his birthdate as 1147 and also notes that the previous year:

- "Randle, earl of Chester, was made prisoner by stratagem by king Stephen at Northampton, August 29. When the Welsh heard of it, they laid waste the province of Chester. Against whom Robert de Montalt the seneschal of Chester advanced to battle with a few armed men, and killed many thousands at Nantwich on September 3."

This creates something of a problem for those who have argued that Hugh was born in north Wales. It is more likely that Hugh'd father Ranulph De Gernon suspected that some such thing could happen and had sent his wife to Powys and his ally Madog ap Maredudd.

History records the donation of lands at Ticknall:

- Chief amongst their benefactors was Maud widow of Ranulph de Gernon. Between 1149 and 1161 with the consent of her son, Hugh, 5th Earl of Chester, she gave them the advowson of St Wystan, Repton, and the working of the quarry there, on condition that so soon as opportunity offered Calke should transfer its endowments to a new priory to be set up at Repton, and itself become simply a cell of its daughter house. About 1162 Hugh confirmed gifts by his father of the wood between Sceggebroc and Aldreboc and Little Geilberga, a culture between Aldreboc and Sudmude [south wood], the little mill of Repton and four bovates of land of Ticknall. He also confirmed gifts by Nicholas the priest of two bovates in Ticknall and the chapel of smisby, by Geva Ridel of s measure of land in Tamworth, and other gifts by his father of lands in Repton and fishing near Chester. The identity of Nicholas the priest is not known but Geva Ridal was the only daughter of Hugh d'Avranches, first Earl of the country palatine of Chester. There was a number of other mid twelfth century gifts to the church of land and the rights in the neighbourhood and in Sutton Bonnington, which Hugh did not confirm.

The first of these dates is very dubious given that Ranulph De Gernon did not die until 1153. Hugh is also said to have granted his manor of Budworth together with a half share interest in the forestership of Mara (which included Delamere Forest) to Robert Grosvenor at some time in the 1150s. The bounds of Grosvenor's bailiwick were described in 1361 as being:

- from Stanford Bridge along the King's highway as far as Northwich, thence following the bounds of the forest as far as the Darley Brook, and thence following the Darley Brook as far as the bounds of Rushton, and then following the bounds of Rushton and Olton as far as Yemelegh Mill and from the mill following the bounds between Eaton and Alpraham as far as the town of Tarporley and then following the bounds of the said forest as far as Stanford Bridge.

Being born in 1147, Hugh would have been a minor at the time and one wonders just how real the grant of the forestership was!

Chester Castle was temporarily in royal hands during the minority of Earl Hugh (1153–62). It appears that it was managed by Simon fitz William and Robert Montalt of Mold. Robert had lost his castle at Mold when Owain Gwynedd had captured the castle for the Welsh in the year following its construction in 1147 and would go on to capture Rhuddlan in 1150. Mold would not be regained until 1167.

In 1157, Henry II received the homage of Malcolm IV, king of Scots, in Chester before invading north Wales. Malcolm was not only King of Scots, but also inherited the Earldom of Northumbria, which his father and grandfather had gained during the wars between Stephen and Empress Matilda. Henry II refused to allow Malcolm to keep Cumbria, but instead granted the Earldom of Huntingdon to Malcolm, for which Malcolm did homage.

With the support of the Prince of Powys Madog ap Maredudd and Owain's brother Cadwaladr ap Gruffydd (whom Owain had recently stripped of his lands in Ceredigion), Henry led an army consisting of one-third of the knights in England and an unknown number of infantry into northern Wales and sent a fleet (led by Henry FitzRoy) to capture Anglesey to cut off Owain's supplies. Owain's army made camp at Basingwerk to block the route to Twthill at Rhuddlan. Henry split from his main army with a smaller force that would march through the nearby Ewloe woods (in modern-day Flintshire) to outflank Owain's army. Sensing this, Owain is said to have sent a large army led by his sons Dafydd ab Owain Gwynedd and Cynan ab Owain Gwynedd into the woods to guard Owain's main force from Henry's outflanking army. Owain split his army and decided to personally lead an extra 200 men into the Ewloe woods to reinforce his sons' armies. When Henry's outflanking force advanced into the wood, they were ambushed by Owain's forces and cut down. The remainder of Henry's force retreated, with Henry narrowly avoiding being killed himself (having been rescued by Roger, Earl of Hertford).

Henry managed to escape back to his main army alive. Not wishing to engage the Angevin army directly, Owain repositioned himself first at St. Asaph, then further west, clearing the road for Henry II to enter into Rhuddlan "ingloriously". Once in Rhuddlan, Henry II received word that his naval expedition had failed. Instead of meeting Henry II at Deganwy or Rhuddlan as the king had commanded, the English fleet had gone to plunder Anglesey and the Norman troops on board had been defeated by the local Welsh soldiers (Henry FitzRoy himself had also been killed). Despite Owain's success in the Ewloe woods and the success of his men on Anglesey, Henry had still succeeded in securing Rhuddlan, and so Owain felt obliged to make peace with him. Owain surrendered the lands of Rhuddlan and Tegeingl to Chester. He also gave Cadwaladr his lands back in Ceredigion, which re-cemented the alliance between the two brothers. Owain also agreed to render homage and fealty to Henry. Henry II had achieved the objective of his campaign with Owain’s forced submission.

Owain ap Gruffydd of Gwynedd was in open rebellion by autumn 1164 and sent several letters to Henry's main rival, Louis VII of France, asking to be considered amongst Louis' "faithful and devoted friends". The Welsh annals spoke of a concerted effort by the Welsh princedoms, which were more usually in competition with each other, to "throw off the rule of the French [i.e. the Angevins]". The "Chester Annals" record that in 1164 "justice was done on the Welsh hostages". In 1165 Henry II used Shrewsbury as his base for another invasion of Wales. This was largely unsuccessful and the only real clash was the "Battle" of Crogen (a small skirmish). His attempt to deal with Owain and Rhys a failure, Henry returned to Shrewsbury and there ordered the blinding of twenty-two hostages held since the 1163 treaty, two of whom were Owain's sons. Henry then visited Chester to meet the ships which he had ordered to harry Gwynedd. 19th century and later accounts of the "battle" rely heavily on David Powel's 1584 Historie of Cambria, an unreliable historical source.

Shortly afterwards Chester appears to have been involved in a further attack, for in 1170 (or 1169) Hugh II was reported in the Chester Annals to have built a mound at Boughton out of the heads of Welshmen killed at the 'bridge of Baldert', possibly Balderton (in Dodleston), south of Chester, with the mound actually having been built at Broughton.

- Hic natus Ranulphus III. filius Hugonis comes Cestrie. In hoc etiam anno interfecit Hugo comes Cestrie magnam multitudinem Walensium juxta pontem de Baldert de quorum capitibus factum unum de aggeribus apud Hospitalem infirmorum extra Cestriam. (This year Randle III., son of Hugh, earl of Chester, was born. In this year also Hugh, earl of Chester, slew a great multitude of Welshmen, near the bridge of Baldert, of whose heads one of the mounds at the hospital for the sick outside Chester is formed.)

The said hospital for the sick stood close by the site of St Giles Cemetery.

Revolt against the king

In 1173, (aged 26) Hugh stuck with family tradition and joined the baronial Revolt of 1173-1174 against Henry II. A leading figure in this revolt was Henry II's heir "Henry the Young King". Henry fell out with his father in 1173. Contemporary chroniclers allege that it was due to the young man's frustration that his father had given him no realm to rule, and that he felt starved of funds. The rebellion seems however to have drawn strength from much deeper discontent with his father's rule, and a formidable party of English and Norman magnates joined him.

- ..many powerful and noble persons, as well in England as in foreign parts, either impelled by mere hatred, which until then they had dissembled, or solicited by promises of the vainest kind, began by degrees to desert the father for the son, and to make every preparation for the commencement of war. The earl of Leicester, for instance, the earl of Chester, Hugh Bigot, Ralph de Fougeres, and many others, formidable from the amount of their wealth and the strength of their fortresses.

The civil war (1173–74) came close to toppling the king, and he was narrowly saved by the loyalty of a party of English court aristocracy and the defeat and capture of the king of Scotland. Hugh had chosen the losing side and lost Chester Castle and the rest of his lands when captured and imprisoned. While shuttled about somewhat he was finally placed in confinement at Caen after the Battle of Alnwick (1174) when William I of Scotland) was defeated.

The "Annales" records it as follows:

- mclxxiij Hic cepit Henricus tercius Rex Anglie filius Henrici Regis Anglie inquictare patrem suum juncto sibi Rege Francie cujus filiam acceperat in uxorem et comite Flandrensi et eorum auxiliis necnon et duobus comitibus Anglie, videlicet Hugone comite Cestrensi et Roberto comite Leicestrie. In hoc etiam anno captus est Hugo comes Cestrie apud Dol in Britanniam a Rege Henrico cum Radulpho de Feugis et aliis multis, et Robertus comes Lecestrie cum sua comitissa captus non longe a monasterio Sancti Edmundi et omnes Flandrenses qui cum eo venerant ut in Angliam guerram facerent sunt a comitibus Angliæ interempti vel vivi capti et retenti. (1173 At this time Henry III., king of England, son of Henry II., king of England, began to disquiet his father in concert with the king of France, whose daughter he had married, and the count of Flanders, and with their assistance, and that of two English earls, namely Hugh, earl of Chester, and Robert, earl of Leicester. In this year also Hugh, earl of Chester, was taken prisoner, at Dol in Brittany, by king Henry [II.] with Ralph de Feugeres and many others. And Robert, earl of Leicester, was taken prisoner with his countess not far from the monastery of S. Edmund, and all the Flemings who had accompanied him for the purpose of making war against England, were either killed by the English earls or captured alive and held prisoners.)

The same events are recorded in the Chronicle of Roger of Hoveden:

- On the following day, the king of England, the father, left Verneuil, and took the castle of Damville, which belonged to Gilbert de Tilieres, and captured with it a great number of knights and men-at-arms. After this, the king came to Rouen, and thence dispatched his Brabanters, in whom he placed more confidence than the rest, into Brittany, against Hugh, earl of Chester, and Ralph de Fougeres, who had now gained possession of nearly the whole of it. When these troops approached, earl of Chester and Ralph de Fougeres went forth to meet them. In consequence of this, preparations were made for battle; the troops were drawn out in battle array, and everything put in readiness for the combat. Accordingly, the engagement having commenced, the enemies of the king of England were routed, and the men of Brittany were laid pros. bate and utterly defeated. The earl, however, and Ralph de Fougeres, with many of the most powerful men of Brittany, shut themselves up in the fort of Dol, which they had taken by stratagem; on which, the Brabanters besieged them on every side, on the thirteenth day before the calends of September, being the second day of the week. In this battle there were taken by the Brabanters seventeen knights remarkable for their valour … . Besides these, many others were captured, both horse and foot, and more than fifteen hundred of the Bretons were slain.

- Now, on the day after this capture and slaughter, "Rumor, than which nothing in speed more swift exists," reached the ears of the king of England, who, immediately setting out on his march towards Dol, arrived there on the fifth day of the week, and immediately ordered his stone-engines, and other engines of war, to be got in readiness. The earl of Chester, however, and those who were with him in the fort, being unable to defend it, surrendered it to the king, on the seventeenth day before the calends of September, being the Lord’s Day ; and, in like manner, the whole of Brittany, with all its fortresses, was restored to him, and its chief men were carried into captivity. In the fortress of Dol many knights and yeomen were taken prisoners … .

So captured at Dol, Hugh is now placed in prison in Falaise.

- There fell in this battle more than ten thousand Flemings, while all the rest were taken prisoners, and being thrown into prison in irons, were there starved to death. As for the earl of Leicester and his wife and Hugh des Chateaux, and the rest of the more wealthy men who were captured with them, they were sent into Normandy to the king the father; on which the king placed them in confinement at Falaise, and Hugh, earl of Chester, with them.

Hugh was brought over to England...

- Immediately on this, he embarked, and, on the following day, landed at Southampton, in England, on the eight day before the ides of July, being the second day of the week, bringing with him his wife, queen Eleanor, and queen Margaret, daughter of Louis, king of the Franks, and wife of his son Henry, with Robert, earl of Leicester, and Hugh, earl of Chester, whom he immediately placed in confinement.

...but later shipped back to France and placed in confinement, first at Caen, and afterwards at Falaise. Hugh is mentioned (as an exception) in the treaty which ended the 1173-1174 revolt.

- ..But, as to the prisoners who have made a composition with our lord the king before this treaty was made with our lord the king, namely, the king of Scotland, the earl of Leicester, the earl of Chester and Ralph de Fougeres, and their pledges, and the pledges of the other prisoners whom he had before that time, they are to be excepted out of this treaty.

However, he had his estates restored in 1177.

Propaganda

After his release from prison in 1177, Hugh may still have harboured ambitions to make Chester the centre of an independent principality. During Hugh's time stories arose that hermits living in the Hermitage (Anchorite Cell) had claimed to be Harold II of England and the German Emperor Henry V. In both cases this is most unlikely, but, in both cases, such claims would cast doubt on Angevin legitimacy:

- Harold II for obvious reasons - if he had lived then the Norman claim would be weakened as the succession passed through William's granddaughter Matilda,

- Henry V because his survival - (he was the first husband of William's grand-daughter Matilda) - would have bastardized the king, Henry II.

It is possible that Hugh was also the source of the myth that Lucy of Bolingbroke (his grandmother) was descended from the House of Leofric.

Hugh died 30 June 1181 (aged 34) at Leek, Staffordshire, England. There was another revolt around Henry the following year, but, on 11th June 1183, Henry the Young King died and that uprising, which had been built around the Prince, quickly collapsed and the remaining brothers returned to the their individual lands.

Sources - Kevilioc

Related Pages

- Ranulph De Gernon: his father;

- Amicia;

- Ranulf de Blondeville: his son

Online

Books

- Paul Meyer, L'Histoire de Guillaume le Maréchal (Paris: Société de l'histoire de France, 1891–1901), with partial translation of the original sources into Modern French. Edition and English translation, History of William Marshal, ed. A.J. Holden and D. Crouch, trans. S. Gregory (3 vols, Anglo-Norman Text Society, Occasional Publication Series, 4-6, 2002-2007).

- Sidney Painter, William Marshal, Knight-Errant, Baron, and Regent of England (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1933; reprint Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1982).

- Georges Duby, William Marshal, the Flower of Chivalry (New York: Pantheon, 1985).

- David Crouch, William Marshal: Knighthood, War and Chivalry, 1147–1219 (2n edn, London: Longman, 2002). A healthy corrective to Duby's excessive reliance on the Histoire.

- John Gillingham, 'War and Chivalry in the History of William the Marshal' in Thirteenth Century England II ed. P.R. Cross and S.D. Lloyd (Woodbridge, 1988) 1–13

- Larry D. Benson, 'The Tournament in the romances of Chrétien de Troyes and L'Histoire de Guillaume le Maréchal' in Studies in Medieval Culture XIV 1980 1–24

- Sidney Painter, "The House of Quency, 1136-1264", Medievalia et Humanistica, 11 (1957) 3-9; reprinted in his book Feudalism and Liberty

- Grant G. Simpson, “An Anglo-Scottish Baron of the Thirteenth century: the Acts of Roger de Quincy Earl of Winchester and Constable of Scotland” (Unpublished PhD Thesis, Edinburgh 1963).

- Robert Bartlett, England Under The Norman and Angevin Kings 1075-1225 (2000)

- Richard Barber, The Devil's Crown: A History of Henry II and His Sons (Conshohocken, PA, 1996)

- J. Boussard, Le government d'Henry II Plantagênêt (Paris, 1956)

- John D. Hosler Henry II: A Medieval Soldier at War, 1147–1189 (History of Warfare; 44). Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, 2007 (hardcover, ISBN 90-04-15724-7).

- W.L. Warren, Henry II (London, 1973)

- John Harvey, "The Plantagenets"