Shakespeare and Chester

The year 1580 saw a spectacular show in the portentous earthquake and blazing comet that marked the year. Published shortly afterwards, Francis Shakelton’s "Blazing Star" warns of "dissolution of the Engine of this World". Shakelton warned of "the Decay of Nature", a concept that became widespread in the 17th century, sanctioning the use of art and science to amend, improve, or replace natural processes. There was a spectacular nova in 1572, another comet in 1577 and another Supernova in 1604. In the ninth episode of James Joyce's Ulysses, Stephen Dedalus associates the appearance of the 1572 supernova with the youthful William Shakespeare, and it has been argued that this supernova is described in Shakespeare's Hamlet, specifically by Bernardo in Act I, Scene i: "Last night of all / When yond same star that's westward from the pole / Had made his course to illume that part of heaven / Where now it burns,". Peter Roberts, proctor of the Consistory Court of St. Asaph, noted in his Cwtta Cyfarwydd: "Md' that in the moneth of November 1618 a strange blazing starre appeared and was seene in the east about vi of the clock in the morning with a long taile upwards towards the weast." The same comet had intrigued James I and after consulting mathematicians from Cambridge he prophesied the outbreak of the Thirty Years' War and the collapse of the Stuart dynasty. It was a time of portents and marvels.

The Chester Mystery Plays are filled with portents and prophecy. These follow a standard religious pattern: a prophecy is made, which later comes "true" and this is then used to justify the truth of as-yet unfulfilled prophecies relating to the future. Following the banning of the Chester Plays 1575 the theatre became intensely regulated under the Master of the Revels. Control over theatre gradually became extended, particularly under Edmund Tylney and the Office acquired the legal power to censor and control playing across the entire country. This increase in theatrical control coincided with the appearance of permanent adult theaters in London. Every company and traveling troupe had to submit a play manuscript to the Office of the Revels. Shakespeare and his contemporaries were forbidden (by official injunction) from staging religious or Biblical content explicitly.

Two possible connections have been proposed between the Mystery Plays and Shakespeare:

- the first is that Shakespeare was at least aware of the Mystery Plays, either at Chester or elsewhere and may have been influenced by them;

- the second is that the author of the "Shakespeare plays" was not the historic Shakespeare but someone associated with Chester;

This article reviews the history of events in and around Chester during the period of the Shakespeare history plays, then explores the evidence for linkage between the Shakespeare plays and Chester. Possibly the only historical character who has generated more theories about his actual identity than Shakespeare is "Jack the Ripper" and one of the few things we can be certain of is that "Will" and "Jack" are not the same person. Even a brief glance at the literature on the "Chester Origins" theory of Shakespeare's plays, and indeed some of his other works, reveals little mention of how the theory relates to sights and places in modern-day Chester, and where Chester is mentioned it is often treated in poor detail, as if the action at Chester happens "off-stage". This article is not an attempt to prove "Shakespeare" was written in Chester, but hopes to shed some light on how the controversy fits into the broader picture and of course into Chester's local history.

Shakespeare's History Plays

The striking of a clock in Julius Caesar illustrates how Shakespeare's plays do not pretend to be accurate history. Even his English "History" Plays contain some clear changes from what actually happened. He appears to be well aware of this, but makes no pretence of being a historian rather than an entertainer. He certainly also embellished some facts and highly simplified or deleted other facts to increase drama and enhance plot. His sources themselves were often very biased toward a version of history that supported Tudor legitimacy (although it is unclear whether that bias was widely known in Shakespeare's time or not). He also definitely shaded some facts and characters one way or another in order to keep the political leaders and censors of his time happy. Before looking for any possible links between the history plays and Chester, these history plays may be summarised as follows:

King John

- King John receives an ambassador from France who demands (with a threat of war) that he renounce his throne in favour of his nephew, Arthur, whom the French King Philip believes to be the rightful heir to the throne. John argues with the Pope and is excommunicated. John orders Hubert to kill Arthur, but Hubert cannot. John attempts to extract gold from monasteries. Arthur dies (possibly murdered). John is poisoned by a monk. The English swear allegiance to Henry who becomes a boy king in 1216. The play was written c. 1596 and is set 1200-1216. Popular representations of John first began to emerge during the Tudor period, mirroring the revisionist histories of the time. The anonymous play "The Troublesome Reign of King John" portrayed the king as a "proto-Protestant martyr", similar to that shown in John Bale's morality play "Kynge Johan", in which John attempts to save England from the "evil agents of the Roman Church". Shakespeare follows these previous depictions and creates a quite anti-Catholic work, but messes with history significantly. "The Troublesome Reign of John, King of England", commonly called The Troublesome Reign of King John (c. 1589) is an Elizabethan history play, probably by George Peele, that is generally accepted by scholars as the source and model that William Shakespeare employed for his own King John (c. 1596). The main historical sources for The Troublesome Reign are thought to be the Chronicles of Raphael Holinshed and Foxe's Book of Martyrs, and perhaps Richard Grafton's Chronicle at Large, which recapitulates much of the material in John Foxe's book.

Edward III

- Edward III (written c. 1596) compresses a very long reign and telescopes history to achieve this, leaving out actual historical characters and creating many anachronisms. It seems that around 40% of the play was written by Shakespeare, the rest possibly by Thomas Kyd, John Jowett and others. It is particularly anti-Scots, for which it was censured at the time of its first performance. It was not included in the first publication of Shakespeare's works, which was published after the Scottish King James had succeeded to the English throne in 1603.

These "early" history plays are followed by the first four plays of the Henriad:

Richard II

- Richard II (written c 1592) spans only the last two years of the king's life, from 1398 to 1400. A dispute between Henry Bolingbroke, the son of John of Gaunt, and Thomas Mowbray, the Duke of Norfolk is to be resolved by a tournament. At the last minute, Richard stops the contest: he banishes Mowbray for life, and giving in to pleas on behalf of Bolingbroke, commutes his son's banishment to six years. When John of Gaunt dies Richard confiscates his estate. Bolingbroke, resenting the confiscation of his inheritance, returns to England where his army is enthusiastically welcomed by the English, led by Henry Percy, the Earl of Northumberland. The play was performed and published late in the reign of Elizabeth I of England, at a time when the queen's advanced age made succession an important political concern. The play ends with the rise of Bolingbroke to the throne, marking the start of a new era in England. Notably, Bolingbroke has a rather weak claim to the throne through bloodline. The play is the first part of a tetralogy, referred to by some scholars as the Henriad, followed by three plays concerning Richard's successors: Henry IV, Part 1; Henry IV, Part 2; and Henry V.

Henry IV (parts 1-2)

- Henry IV (written c 1597) has usurped his cousin, Richard II, to become King of England. News comes of a rebellion in Wales, where his cousin, Edmund Mortimer, has been taken prisoner by Owen Glendower, and in the North, where Harry Hotspur, the young son of the Earl of Northumberland, is fighting the Earl of Douglas. Prince Hal spends all his time in the London taverns with disreputable companions, particularly one dissolute old knight, Sir John Falstaff. Hal is reconciled with the king. The King’s army triumphs over the rebels. The king dies and Hal becomes Henry V.

Henry V

- Henry V’s father Bolingbroke (Henry IV) was never able to rule comfortably because he had usurped Richard II. On his succession King Henry V is determined to prove his right to rule, including over France. The French are defeated, with heavy losses, whereas the English losses are light. Henry returns to London in triumph before making peace with the French king. The play was written c 1599.

The second four plays of the Henriad were written earlier than the preceeding set of four:

Henry VI (parts 1-3)

- Henry VI (written c 1590) opens in the aftermath of the death of King Henry V. The lords select red or white roses, depending on whether they favour the House of Lancaster or that of York. The country descends into Civil War. Richard of Gloucester begins his campaign to remove all obstacles in his path to the throne by murdering King Henry VI who is a captive in the Tower of London. Henry prophesies Richard’s career of villainy and his future notoriety. Sir Thomas More's History of Richard III explicitly states that Richard killed Henry. However, another contemporary source, Wakefield's Chronicle, gives the date of Henry's death as 23 May, on which date Richard is known to have been away from London. King Henry VI was originally buried in Chertsey Abbey; then, in 1484, his body was moved to St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, by, of all people, Richard III.

Richard III

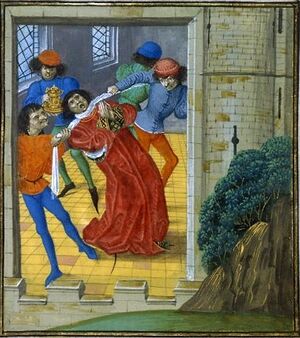

- Richard III (written c 1583) starts as Richard, Duke of Gloucester, determined to gain the crown from his brother, the ill Yorkist King Edward IV. He organises the murder of his brother George, Duke of Clarence, whom he has had imprisoned in the Tower of London. Richard places the young sons of Edward in the Tower and consolidates his power. The king dies and Richard is proclaimed king. The young princes are murdered in the Tower. Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond, the heir to the Lancastrian claim to the throne, makes war on Richard and defeats him becoming Henry VII.

Henry VIII

- Henry VIII married to Katherine for twenty years, decides that the marriage is not legal because she is the widow of his brother, and it is therefore incest. The new Archbishop of Canterbury has a plot hatched against him by Wolsey’s secretary, Gardiner, who is tried and executed for treason. Henry has a daughter, Elizabeth, by Anne Bullen. Cranmer christens her and makes a speech foretelling a noble rule for Elizabeth and a glorious period of history during her reign. The play was written c 1613 - one of the last plays. Stylistic evidence indicates that individual scenes were written by either Shakespeare or his collaborator and successor as house playwright for the King's Men, John Fletcher. During a performance of Henry VIII at the Globe Theatre in 1613, a cannon shot employed for special effects ignited the theatre's thatched roof (and the beams), burning the original Globe building to the ground.

In summary, Shakespeare's history plays follow "real" history to some extent but mess around with the details. Sometimes this might be because the author did not have accurate sources, in other cases it may be simply to create a more dramatic story. Timelines are often compressed bringing events much closer together in the plays than they were in reality. Often, the various theories for the "true identification of Shakespeare" make much of these differences in detail.

Richard II, Henry IV and Chester

Shakespeare became active as a playwright in the reign of Elizabeth I, the last monarch of the house of Tudor, and his history plays are often regarded as Tudor propaganda because they show the dangers of civil war and celebrate the founders of the Tudor dynasty. In particular, "Richard III" depicts the last member of the rival house of York as an evil monster ("that bottled spider, that foul bunchback'd toad"), a depiction disputed by many modern historians, while portraying his successor, Henry VII in glowing terms despite his being a usurper. Shakespeare made use of the Lancaster and York myths, as he found them in the chronicles, as well as the Tudor myth. The "Lancaster myth" regarded Richard II's overthrow and Henry IV's reign as providentially sanctioned, and Henry V's achievements as a divine favour. The "York myth" saw Edward IV's deposing of the ineffectual Henry VI as a providential restoration of the usurped throne to the lawful heirs of Richard II.

Writing plays about political subjects was always a problem in Elizabethan England, so a good choice for "real" history would be the Lancastrians and Yorkists who came along beforehand (and were defeated by) the Tudors. An author could then still drop hints about more recent events and stir up some interest in the play. Even so, it might still be possible to cause offence, for which the penalty could be beheading, so any author needed to be cautious.

Chester 1399-1424

The Chester Mystery Plays were originally associated with the Corpus Christi procession. Some hold that the feast of Corpus Christi was proposed by Thomas Aquinas to Pope Urban IV (1261-64), in order to create a feast focused solely on the Eucharist. Others note that Thomas Becket (1118–70) was consecrated Archbishop of Canterbury on the Sunday after Pentecost (Whitsun), and his first act was to ordain that the day of his consecration should be held as a new festival in honour of the Holy Trinity. Whatever it's origins, the feast is liturgically celebrated on the Thursday after the first Sunday after Pentecost in the Western Christian liturgical calendar.

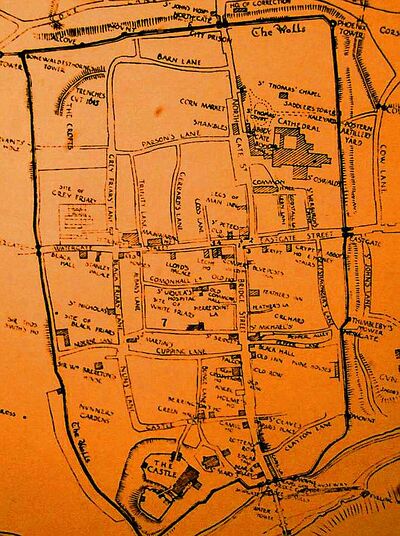

The first possible reference to the Corpus Christi procession in Chester is an inauspicious one - a record of 1399 describes a terrible brawl which broke out between the members of the guilds of the Weavers, Shearmen, Challoners (blanket-makers) and the Walkers (fullers) against their apprentices, outside the guild church of St Peter. 1399 was the last year of Richard II's reign, who had taken the title of "Prince of Chester" for himself in 1398 and was known for his "Chester Guard" - he was soon to be deposed and imprisoned briefly at Chester Castle. In 1424 a further Corpus Christi riot came just after a supposed "royal visit" by Henry VI (then still a child) - it was a time of great political instability: Henry was the youngest person ever to succeed to the English throne, at the age of nine months on 1 September 1422, the day after his father's death. The period between these two riots is covered by the first four plays of the Henriad.

As regards Chester, Richard II visited in 1387 and found the town greatly impoverished with a ruined bridge over the Dee. He made his "favourite" Robert de Vere Justice of Chester. De Vere did not last long and was replaced after a rebellion the following year. Unrest in Chester continued for many years. Richard formed a notorious "Chester Guard" and also errected Chester to a principality with himself as "Prince of Chester". In 1399, while Richard II was away on a military campaign in Ireland, Henry Bollingbroke, later Henry IV, landed in Britain after exile and took Chester without a fight. He stayed at Chester for a few days and then captured Richard II who was briefly imprisoned at Chester Castle. Richard's treasure was reputedly hidden somewhere near Chester (often cited as down the well at Beeston Castle - England’s deepest medieval well).

The Rise of the Stanleys

The Stanley family became powerful during the reign of Richard II. Sir William de Stanley was Master-Forester of the Forest of Wirral and was notorious for his repressive activities. His son, John Stanley led an expedition to Ireland on behalf of de Vere and King Richard II to quell rebellion. John had married (1385) a wealthy heiress, Isabel Lathom, which, combined with his own abilities, allowed him to rise above the usual status of a younger son. Both John Stanley and his elder brother, William Stanley (who succeeded their father as Master-Forester), were involved in criminal cases which charged them with a forced entry in 1369 and with the murder of Thomas Clotton in 1376. Conviction for the murder of Clotton resulted in Stanley being declared an outlaw. However, he was already distinguishing himself in military service in the French wars, and he was pardoned in 1378 at the insistence of his commander, Sir Thomas Trivet.

John: Shrewsbury and Man

In 1389, Richard II appointed John justiciar of Ireland, a post he held until 1391. He was heavily involved in Richard's first expedition to Ireland in 1394–1395. However, on his return to England, Stanley, who had long proved adept at political manoeuvrings, turned his back on Richard and submitted to Henry IV of England. Stanley's fortunes were equally good under the Lancastrians. He was granted lordships in the Welsh marches, and served a term as lieutenant of Ireland. In 1403 he was made steward of the household of Henry, prince of Wales, (later Henry V). Unlike many of the Cheshire gentry, he took the side of the king in the rebellion of the Percys. He was wounded in the throat at the Battle of Shrewsbury (21 July 1403). On the 16th September, not two months after the battle, the Prince appointed Sir John Stanley to be keeper of the county of Chester, and "to resist the malice of the Welsh rebels round about". In 1405 he was granted the tenure of the Isle of Man by which had been confiscated from the rebellious Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland. The precise nature of this appointment to Man would come back as an issue two-hundred years later. In this period he also became steward of the king's household, and was elected a Knight of the Garter. In 1413 King Henry V of England sent him to serve once more as lieutenant of Ireland.

It has been suggested that John Stanley was the as-yet unidentified "Gawain Poet". The Garter motto "Honi soit qui mal y pense" appears at the end of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, and the poet exhibits a detailed knowledge of both hunting and armour. Scholars identify the poet's dialect as that of north-west Staffordshire or south-east Cheshire. Several scholars have attempted to find a real-world correspondence for Gawain's journey to the Green Chapel. The Anglesey islands, for example, are mentioned in the poem. They exist today as effectively a single island off the coast of Wales. In line 700, Gawain is said to pass the "Holy Head", believed by many scholars to be either Holywell or the Cistercian abbey of Poulton in Pulford. Holywell is associated with the beheading of Saint Winifred. As the story goes, Winifred was a virgin who was beheaded by a local leader after she refused his sexual advances. Her uncle, another saint, put her head back in place and healed the wound, leaving only a white scar. The parallels between this story and Gawain's make this area a likely candidate for the journey.

In 1403 Sir Henry Percy ('Hotspur'), lately justice of Chester, stayed in the city and raised the standard of revolt there, where former kings men and veterans of the Cheshire Guard still resided by the hundreds. Percy formed an alliance with the Welsh rebel, Owain Glyndŵr. Before they could join forces, Hotspur was defeated and killed at the Battle of Shrewsbury as he raised his visor to get some air (he was wearing full plate) and was hit in the mouth with an arrow.

The single most intriguing event taking place before the Battle of Shrewsbury was the defection from the royal army (and therefor from the Kings' Peace) of Hotspur’s uncle the Earl of Worcester just days before the battle was fought. The impact militarily, on paper at least, was significant, the Earl of Worcester bringing 1,000 men, mostly archers and lightly armed men of foot, over to Hotspur's rebel army. After Percy's defeat one of the quarters of his body was sent to Chester, together with the heads of Sir Richard Venables and Sir Richard Vernon. Chester was not wholly on the side of the rebels as the mayor and the constable of the castle were present at Shrewsbury in the king's retinue.

The future (then sixteen-year-old) Henry V (Prince Hal) was also struck by an arrow which became stuck in his face "to a depth of six inches". Over a period of several days John Bradmore, the royal physician, treated the wound with honey to act as an antiseptic, crafted a special tool to screw into the broken arrow shaft and extract the arrow. The operation was successful, but it left Henry with permanent scars and explains why the one remaining contemporary portrait (see below) shows only the left side of his face. Legislation of 1403, vigorously supported by the mayor of Chester, denied any arms to the Welsh - except a knife to eat with. It is from this time that the Shoot the Welsh story comes from In the weeks following the Battle of Shrewsbury the insecurity of both the new dynasty and some of the city authorities (i.e. those who had been on the King's side at the battle) was demonstrated in the instructions issued by Prince Henry in response to further defections in north Wales. On September 4, 1403, he wrote to the Mayor, Sheriffs and Aldermen of the City of Chester, who were required to impose a curfew upon all Welshmen visiting Chester, and to ensure that they left their arms at the city gates and did not gather in groups of more than three; all Welsh residents were expelled and any who stayed overnight were threatened with execution. Apparently, the actual wording was that: "all manner of Welsh persons or Welsh sympathies should be expelled from the city; that no Welshman should enter the city before sunrise or tarry in it after sunset, under pain of decapitation.". William de Venables, constable of Chester, with the steward and others of the prince's household took the field with the armed forces of Cheshire to resist an imminent invasion by Owain Glyndŵr.

Thomas Stanley: 1st Earl of Derby

Sir John Stanley (c. 1386–1437) was Sheriff of Anglesey, Constable of Carnarvon, Justice of Chester, Steward of Macclesfield and titular King of Mann. He twice visited the Isle of Man to put down rebellions (1417 and 1422) and was also responsible for putting the laws of the Island into writing. Thomas Stanley, 1st Baron Stanley was the son of John (II) Stanley by his wife, Elizabeth, daughter of Sir Nicholas Harington (or Haverington) of Farleton (in Melling), Lancashire. He represented Lancashire in the House of Commons in 1427, 1433, 1439, 1442, 1447, 1449, 1450, 1453, 1455. After the death of his father in 1459, Thomas Stanley inherited his father's titles, including those of Baron Stanley and King of Mann as well as his extensive lands and offices in Cheshire and Lancashire. It was a formidable inheritance and gave him ample opportunity to gain experience in the leadership of men. At the same time, his father's prominence in the king's household had provided him with an early introduction to court where he was named among the squires of Henry VI in 1454.

The Death of Henry V

The sudden death of Henry V, in 1422, from what may well have been drinking water while in France, led to civil war in England. The Wars of the Roses were fought between supporters of two rival cadet branches of the royal House of Plantagenet: the House of Lancaster, associated with the Red Rose of Lancaster, and the House of York, whose symbol was the White Rose of York. Eventually, the wars eliminated the male lines of both families. The power struggle ignited around social and financial troubles following the Hundred Years' War, unfolding the structural problems of bastard feudalism, combined with the mental infirmity and weak rule of King Henry VI which revived interest in the House of York's claim to the throne by Richard of York. Historians disagree on which of these factors to identify as the main reason for the wars. Chester was on the Lancastrian side. In 1450 Sir Thomas Stanley (then Justice of Chester) called upon to supply troops to support the Lancastrians. In 1455 he mobilized a large force from Cheshire to help the Lancastrian cause, but arrived late for the Battle of St Albans (22nd May). In 1459 he turned up late for the Battle of Blore Heath.

Although relations with the crown cooled and (not least from the election of a Welsh mayor) there seems to have been much sympathy with Wales in Chester. Prior to his return, the Stanleys had been communicating with the exiled Henry Tudor for some time and Tudor's strategy of landing in Wales and heading east into central England depended on the acquiescence of Sir William Stanley, as Chamberlain of Chester and north Wales, and by extension on that of Lord Thomas Stanley, 1st Earl of Derby himself. On hearing of the invasion, Richard III ordered the two Stanleys to raise the men of the region in readiness to oppose the invader. However, once it was clear that Tudor was marching unopposed through Wales, Richard ordered Lord Stanley to join him without delay.

According to the Crowland Chronicle, Lord Stanley excused himself on the grounds of illness, claiming that he was suffering from the 'sweating sickness', although by now Richard had firm evidence of the Stanleys’ complicity. After an unsuccessful bid to escape from court, Lord Strange (George Stanley) had confessed that he and his uncle, Sir William Stanley, had conspired with Henry Tudor. Richard proclaimed him as a traitor, and let it be known that Strange’s life was hostage for his father's loyalty in the coming conflict. Indeed, Richard allegedly issued orders for Strange’s execution on the battlefield at Bosworth Field, although in the event these were never carried out. The failure of Lord Stanley, to come to the aid of King Richard III at Bosworth contributed to King Richard's defeat. Lord Stanley, who was by then married to the future Henry VII's mother, Margaret Beaufort, is given a major role in Shakespeare's Richard III.

George Stanley is said to have been poisoned at a banquet in 1503 predeceasing his father. George Stanley's son was Thomas Stanley, who became the 2nd Earl of Derby. Next came Edward Stanley, 3rd Earl of Derby whose father died when Edward was 13. In 1554, Protestant martyr George Marsh (burnt at Boughton), was questioned at Lathom House by Edward Stanley. Edward's eldest son was Henry Stanley the father of Wiilliam and Ferdinando. Henry seems to have had almost continual financial problems, so much so that his father Edward conveyed the Stanley estates to trustees in March 1570, entailing them on the male heirs. This was evidently to prevent Henry from dissipating his inheritance. None of the Stanleys from George to Edward were in line for the English throne or appear to have been involved in any conspiracy to gain it.

The "Stanley" sucession

Events had however conspired to set up a complex succession problem from which the Stanleys could benefit. Henry Tudor had two sons, the eldest of which (Arthur) died young leaving the younger son to become Henry VIII. Henry had a sister Mary. Three of Henry's children ruled England: Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth. Henry VIII's Third Succession Act granted Henry the right to bequeath the Crown in his Will. His Will specified that, in default of heirs to his children, the throne was to pass to the children of the daughters of his younger sister Mary Tudor, Queen of France, bypassing the line of his elder sister Margaret Tudor, represented by the Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots.

Edward VI confirmed this by letters patent. In June 1553, Edward VI wrote his will, nominating Jane Grey and her male heirs as successors to the Crown, in part because his half-sister Mary was Roman Catholic, while Jane was a committed Protestant and would support the reformed Church of England, whose foundation Edward claimed to have laid. The will removed his half-sisters, Mary and Elizabeth, from the line of succession on account of their illegitimacy, subverting their claims under the Third Succession Act. After Edward's death, Jane was proclaimed queen on 10 July 1553 and awaited coronation in the Tower of London. Support for Mary grew very quickly, and most of Jane's supporters abandoned her. The Privy Council of England suddenly changed sides and proclaimed Mary as queen on 19 July 1553, deposing Jane. Her primary supporter, her father-in-law the Duke of Northumberland, was accused of treason and executed less than a month later. Jane was held prisoner at the Tower and was convicted in November 1553 of high treason, which carried a sentence of death—though Mary initially spared her life. However, Jane soon became viewed as a threat to the Crown when her father, Henry Grey, 1st Duke of Suffolk, got involved with Wyatt's rebellion against Queen Mary's intention to marry Philip II of Spain. Both Jane and her husband were executed on 12 February 1554. Mary was the queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 until her death. She is best known for her aggressive attempt to reverse the English Reformation, and was succeeded by Elizabeth.

According to the will of Henry VIII, Margaret Clifford (Ferdinando Stanley's mother) was in line to inherit the throne of England. Upon the death of her mother, Margaret became seventh in line. However, both her cousins Lady Jane Grey and Lady Mary Grey died without issue, and their sister, her other cousin, Lady Catherine Grey, died without the legitimacy of her two sons ever being proven (this was later established but only after the death of Elizabeth I). Margaret quickly moved up to becoming the first in line to the throne but died prior to the death of Elizabeth I. The legitimate and legal heir of Elizabeth I was now Anne Stanley, Countess of Castlehaven (the marriage of Lady Catherine Grey having been annulled, and her children declared illegitimate, by Elizabeth I).

The links of the "Stanley Succession" to Chester need to be seen in context. William Stanley lived at least in his later years at Chester, but he was never in the actual line of sucession. Stanley Palace was never the main home of the Stanley's: that was Lathom House near Manchester. The stone-built castle known as Lathom House, built by the Stanley family in 1496, had eighteen towers, and was surrounded by a wall six foot thick and a moat eight yards wide, its drawbridge defended by a gateway tower. In the centre of the site was a tall tower known as the Eagle Tower - that was a far more impressive building than Stanley Palace.

Thomas Egerton married as his third wife, on 20th October 1600, Alice Spencer, daughter of Sir John Spencer and widow of Ferdinando. The marriage was a disaster. She joined Egerton’s household with a retinue of 40 persons, estimated as being likely to add at least £650 a year to his household expenses. By 1610 Egerton, now lord chancellor and a peer, was describing his wife as extravagant, greedy and ill-tempered, with a:

- cursed railing and bitter tongue ... I thank God I never desired long life, nor never had less cause to desire it than since this, my last marriage, for before I was never acquainted with such tempests and storms.

Stanleys and the theatre

As discussed below, Henry Stanley, 4th Earl of Derby, came to Chester (in 1578) to see a performance of the "Shepherds Play". It is known from the household book of the Steward to Henry for the period from 1586 to 1590 that a number of the leading English acting companies performed at both Knowsley and at the Stanley family’s main seat at Lathom House near Ormskirk. These companies included The Queen’s Men, as well as those of her two great favourites, the Earl of Leicester’s Men and the Earl of Essex’s Men.

The Earls of Derby had a close interest in the market town of Prescot, whose governance they kept a close eye on through the stewards of the town. In the mid-1590s a gentleman called Richard Harrington – whose brother Percival Harrington was deputy steward built the Prescot Playhouse on one of the main street of the town. This building, which operated as a theatre until at least 1609 and possibly until 1617, is one of the very few purpose-built indoor theatres to have been constructed outside London during the late Elizabethan and Jacobean periods. It would have been used by touring acting companies that were visiting Knowsley Hall and Lathom House in addition to other nearby locations in the North West of England. It has been suggested that the playhouse was built sometime between 1593 and 1595, with the backing of either Ferdinando Stanley or William Stanley, as a purpose-built venue for their actors, known as Lord Strange's Men or the Earl of Derby's Men, when they were forced out of London by the 1592 plague outbreak.

William Shakespeare

The "official" version is that William Shakespeare (bapt. 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English poet, playwright, and actor, widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's greatest dramatist. Shakespeare was born and raised in Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire. At the age of 18, he married 26 year old Anne Hathaway, with whom he had three children: Susanna and twins Hamnet and Judith. The consistory court of the Diocese of Worcester issued a marriage licence on 27 November 1582. The next day, two of Hathaway's neighbours posted bonds guaranteeing that no lawful claims impeded the marriage. The ceremony may have been arranged in some haste since the Worcester chancellor allowed the marriage banns to be read once instead of the usual three times, and six months after the marriage Anne gave birth to a daughter, Susanna, baptised 26 May 1583.

Sometime between 1585 and 1592, Shakespeare began a successful career in London as an actor, writer, and part-owner of a playing company called the Lord Chamberlain's Men, later known as the King's Men, for which Shakespeare wrote during most of his career. Richard Burbage played most of the lead roles, including Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, and Macbeth. Formed at the end of a period of flux in the theatrical world of London, it had become, by 1603, one of the two leading companies of the city and was subsequently patronized by James I. The Lord Chamberlain's Men were formed out of Lord Strange's Men comprising retainers of the household of Ferdinando Stanley, Lord Strange. It is not certain to what extent Shakespeare was involved with Lord Strange's men.

Strange's Men appear to have begun a provincial tour in May 1593, after the London theatres were closed due to plague. Only some fragments of documentary evidence enable us to glimpse parts of it. In early May, they were in Chelmsford, Essex. Later in the summer they visited Sudbury and Faversham. In July, they were in Southampton. In July and August, they headed west to Bath and Bristol. They then turned north and visited Shrewsbury, from where they may have gone on to Chester and York. In December, they were in Leicester and Coventry before they returned to London. Ferdinando Stanley died in April 1594.

The touring company could not have seen the mystery plays because they were last performed in 1575. The crucial dates are 1569 (the last performance of the York cycle - Shakespeare would have been 5), 1575 (the last performance of the Chester cycle - Shakespeare would have been 11), 1576 (the prevention of an attempt to perform the Wakefield cycle), and 1579 (the last performance of the Coventry cycle - Shakespeare would have been 18). However Shakespeare could not have seen any Old Testament material at Coventry as since the 1530s it had consisted of only ten pageants covering exclusively New Testament material from the Annunciation to Doomsday. There is in fact no hard evidence that the Coventry cycle ever contained any Old Testament episodes and, if it had done so, it had certainly ceased to do so by the time of Shakespeare.

Shakespeare included in his plays more child roles than did his contemporaries. Children in Shakespeare's world often exist as figures in someone else's play; as royal pawns in adult power games they are the often the fragile vessels of dynastic ambition. Their deaths can by mysterious as with Arthur in King John or Mamillius in the Winter's Tale. Children are murdered in MacBeth, Richard III and threatened with death in Henry V. The fate of children in Shakespeare offers a view of English history as a tragedy of failed succession, a viewpoint which could politically trouble triumphant Elizabethan providentialism. But there is also a personal angle. Sometime in the spring or summer of 1596 Shakespeare must have received word that his only son Hamnet, eleven years old, was ill. Whether in London or on tour with his company he would at best have only been able to receive news intermittently from his family in Stratford, but at some point in the summer he presumably learned that Hamnet’s condition had worsened and that it was necessary to drop everything and hurry home. By the time the father reached Stratford the boy—whom, apart from brief visits, Shakespeare had in effect abandoned in his infancy—may already have died. On August 11, 1596, Hamnet was buried at Holy Trinity Church: the clerk duly noted in the burial register, “Hamnet filius William Shakspere.”

The play "Hamlet" illustrates very well how Shakespeare was influenced by earlier works. The immediate source of Hamlet is an earlier play dramatising the same story of the Danish prince who must avenge his father. No printed text of this play survives and it may well have been seen only in performance and never in print. References from the late 1580s through to the mid 1590s testify to its popularity and to the presence of a ghost crying out for revenge. There is general scholarly agreement that the author of this early version of Hamlet was Thomas Kyd, famous as the writer of the revenge drama, The Spanish Tragedy. This play did survive in print and was a huge theatrical hit in the late 1580s and 90s, delighting the contemporary taste for intrigue, bloodshed and ghostly presences. However Kyd and Shakespeare were only the latest spinners of an age-old yarn originating in the ancient sagas of Scandinavia. It was written down in manuscript form in the twelfth century by the Danish scholar, Saxo Grammaticus, in his Gesta Danorum and it finally found its way into print in 1514. It is the story of the murder of a Danish ruler by his brother (Fengi = Claudius), swiftly followed by the marriage of the widowed queen (Gerutha = Gertrude) to the murderous brother, the assumed madness of the dead king's son (Amleth = Hamlet) and his voyage to England during which he alters the letters bearing his death warrant, and his return to avenge himself upon his father's killer.

At age 49 (around 1613), he appears to have retired to Stratford, where he died three years later. Few records of Shakespeare's private life survive; this has stimulated considerable speculation about such matters as his physical appearance, his sexuality, his religious beliefs, and whether the works attributed to him were written by others.

The Shakespeare authorship question is the argument that someone other than William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon wrote the works attributed to him. Anti-Stratfordians—a collective term for adherents of the various alternative-authorship theories—believe that Shakespeare of Stratford was a front to shield the identity of the real author or authors, who did not want or could not accept public credit.

Some of the anti-Stratfordian theories associate "Shakespeare" with an author who lived in or near Chester. The next section looks at the historical evidence for links between Shakespeare and Chester and the following section looks at the theories concerning one particular authorship candidate: William Stanley.

Shakespeare and Chester

There are some links between Shakespeare and Chester, but they are rather obscure as well as being rather odd. The possible connections to the Chester Mystery Plays is discussed below, but there are two other links that are worth noting:

The clock at St Peter

A new (perhaps the first) mechanical clock was made for St Peter in about 1585 by William Sampson, who appears to have also been a blacksmith and was awarded the freedom of the ciry in recompence. Curiously, there was also a William Sampson clockmaker of Stratford-on-Avon, who got into some kind of legal trouble at St Brides, London and needed surety for bail before the Queens Bench. The bail (£19) was apparently provided, in 1597, by one Gilbert Shakespeare (haberdasher), who is believed to have been the brother of the somewhat better-known William. It is impossible to say with any certainty that these two William Sampsons, both alive at the same time and both clockmakers, are one and the same person: see Clockmaker for more.

The Sonnets

Thomas Thorpe (or Thropp) (c. 1569 – c. 1625) was an English publisher, most famous for publishing Shakespeare's sonnets and several works by Christopher Marlowe and Ben Jonson. The 1609 quarto of Shakespeare's sonnets include a dedication to "Mr. W.H." whose identity has been much speculated upon. Geoffrey Caveney, an American researcher, has unearthed possible evidence to link the initials with William Holme, who had both personal and professional connections to Thorpe. Both possibly came from prominent Chester families, were publishing apprentices in 1570s London and had strong connections with theatres through publishing major playwrights such as Ben Jonson and George Chapman. The suggestion has been made that "W.H." is William Holme, and that this is the same William Holme who lived in Chester, or a relative, possibly the eldest brother of Randle Holme, another William, who died in 1607. This second William Holme was apprenticed to his uncle in 1581 and admitted to the London Stationers Company in 1589. See: Bookseller for more.

An even more obscure connection is the rather radical theory about a Richard Thropp of Chester is that he was actually a run-away Christopher Marlowe, who had escaped an assassination attempt (May 1593) in London (or faked it), and consequently assumed the identity of a real Thropp who remained in London. There is a good deal of speculation about Marlowe in various publications. The facts of his life are that he was born in early 1564, and active as a playwright from 1587, being patronised by Ferdinando Stanley. If Thropp arrived in Chester around 1635 he would have been far too old to be Marlowe. However given the connection between the Thropp of Chester and Thorpe of London there may be an interesting tale still waiting to be discovered. The one link between Marlowe and Chester that is on firmer ground is that one of Marlowes better-known works is Dido, Queen of Carthage (published 1594) appears related to a play performed in Chester in 1563 (see: Queen Dido for more).

Shakespeare and Mystery Plays

Links can be found between the wording of the Chester Mystery Plays and the works of Shakespeare. Some of the links are relatively clear and others are admittedly quite strained. It can be proposed that either Shakespeare's work arose out of a general theatrical background which included the Mystery Plays or that there was a specific input from the Chester Plays. Once again the crucial dates are 1569 (the last performance of the York cycle - Shakespeare would have been 5), 1575 (the last performance of the Chester cycle - Shakespeare would have been 11), 1576 (the prevention of an attempt to perform the Wakefield cycle), and 1579 (the last performance of the Coventry cycle - Shakespeare would have been 18 - and soon to be married "in haste").

While there are links between the works of Shakespeare and Chester/Cheshire, these may be co-incidence and might not stretch to the Chester Mystery Plays themselves. The "source" could be another Mystery tradition, such as York. Some examples are given below:

- In the Shepherds play the otherwise silent Shepherd boys present gifts which include a bottle, a hood/cape, a pipe (as in musical instrument, possibly a Pibgorn) and a nut-hook. Shakespeare uses "nut-hook" twice: in Merry Wives of Windsor Act I scene I and in Henry IV Part 2 Act V scene IV). It is not clear whether the reference to a "nut-hook" is a reference to a bishop's crosier.

- Twice in Shakespeare’s plays, Judas is described as treacherously greeting Christ with the words “All hail!” (Richard II, Act IV. sc. 1 - "DID they not sometime cry ‘All hail!’ to me, So Judas did to Christ: but he in twelve, Found truth in all but one" and Henry VI, Part 3, Act V. sc. 7 - "So Judas kiss’d his master; And cried—‘All hail!’ when as he meant—all harm"). This phrase does not occur in any version of the Bible available to Shakespeare (it was later introduced as Matthew 26.49 - the original having been something like "peace upon thee, rabbi") but it does occur in the York episode of the "Agony in the Garden" and the "Betrayal" (not in the Chester version), and Shakespeare’s repeated use of the phrase implies a familiarity with something popular and at the time non-biblical, although the York plays were suppressed in 1569 and Shakespeare was not born until 1564. Shakespeare uses similar language in MacBeth at a stage in the play where MacBeth has not yet become the anti-hero.

There is a rather more definite connection between the Stanleys and the Mystery plays found in the Chester Mayor's book (List 13) which relates to a performance in 1578 (William Stanley would have been 17):

- "Henrye Earle of darbye: with his sonne. fardinando. Lord Strange. Came to this Cittye in August. and was honoruably received. by the mayor into his howse and did lye there two Nightes: mr parvise Scollers: plyd A Commodie out of the book of Terence before hym. The Shepeards playe played at the hie Crosse. with other Trivmphes vpon the Rode eye, Also the Two Sheriffes: had bene the mayor prenteses in former tyme / Master Maior. A citizin borne" (REED. Cheshire, vol. 1, 182; REED: Chester 124).

The "Shepherds Play", performed in the Mystery Cycle by the Painters, Glaziers, (Stationers) and Embroiderers seems to have been a favorite for Chester to put on for notable visitors. Here it is being put (1578) on after the rest of the plays had been supressed in 1575. Henry Stanley has an even more convoluted connection to both Chester and Shakespeare via the work of "Robert Chester", the mysterious author of the poem Love's Martyr which was published in 1601 as the main poem in a collection which also included much shorter poems by William Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, George Chapman and John Marston, along with the anonymous "Vatum Chorus" and "Ignoto". Despite attempts to identify Chester no information has ever emerged to indicate with any certainty who he was. Currently all that is known of Chester is his name (which may well be a pseudonym), the long poem he published, and a few unpublished verses. The poem's meaning is deeply obscure. Even the authenticity of the date on the title page has been questioned. It is also not known why Shakespeare and so many other distinguished poets supplemented the publication of such an obscure person with their own works. It has been suggested that the poem celebrated the marriage of Sir John Salusbury and his wife Ursula Stanley, the illegitimate daughter of Henry Stanley.

Shakespeare's Plays and Chester

Although the name William Shakespeare is listed with that of Rowley on the title page of the 1662 quarto of "The Birth of Merlin", this is generally agreed to have been a marketing ploy. The play has a reference to Edol, Earl of Chester (no actual earl had this name) and possibly to the "Rood of Chester" a supposed fragment of the cross venerated at St Johns. Edol is portrayed as living at the time of Vortigern, i.e. shortly after the Roman departure and before the arrival of the Saxons in Chester.

Some of the plays definitely known to have been written by "Shakespeare" have definite links to events in Chester/Cheshire, whereas in other cases possible links are based on misinterpretation:

King Lear

There has been much confusion over the years between references to Caerleon, Leicester, Carlisle and Chester. Much of this goes back to Geoffrey of Monmouth, the Polychronicon and Henry Bradshaw who wrote:

- "The founder of Chester, as saith Polychronicon, Was Leon Gauer, a mighty strong giant; Which builded caves and dungeons many a one, No goodly buildings ne proper, ne pleasant. But King Leil, a Briton sure and valiant, Was founder of Chester by pleasant building, And of Caerleil also named by the King . "

Geoffrey of Monmouth identified Leir as the eponymous founder of the city of Leicester (Ligoraceastre in Old English; Old Welsh: Cair Lerion, Welsh: Caerlŷr), which he called (using the Old Welsh form of the city's name) Kaerleir ("City of Leir"). John Speed, the noted cartographer from Farndon wrote:

- "..and from them (no doubt) by the Britons the place was called Caer Legion; by Ptolemy Deunana, by Antoine Deva, by the Saxons West-Chester, but Henry Bradshaw will have it built before Brute, by the giant Leon Gawr, a man beyond the moon and called by Marius the vanquisher of the Picts... King Leir - a Briton fine and valiant, was founder of Chester by pleasant building, which was named Guer Leir by the King"

All this seems to be possible mistranslation of the Welsh "Caer Le[gi]on Fawr" (large camp of the legions).

Leir's life was dramatised on the Elizabethan stage in an anonymous play, "King Leir", which was registered in 1594 and published in 1605 under the title "The True Chronicle History of King Leir, and his three daughters, Gonorill, Ragan, and Cordella". This precursor to Shakespeare's tragedy was a comedy, repeating Geoffrey's story and ending happily with Leir's restoration to power. Several of Shakespeare's plays are "re-writes" of this kind often dating from before either Shakespeare or the other suggested authors of "Shakespeare" could have been expected to be writing.

King John (mid 1590's)

The parallel between the Abraham and Isaac play and Hubert's preparations to blind the young Arthur in King John has been noted by several scholars. Hubert is given direct orders by his "Lord" to maim a boy he has in some ways treated as a son. Maiming by blinding and possibly also castration was a recognised way of ensuring that a dynastic rival was not only incapable of ruling, but also incapable of producing heirs. It fell short of actual killing and therefore was not against the commandment against killing and was quite common in the Byzantine Empire.

The historic Arthur is of course connected with Chester, being the adopted son of Earl of Chester Ranulf de Blondeville (who does not appear in the play), and named as heir by Richard I. The strange mixture of childish terror and quiet obedience which is found most strikingly in the Chester and Brome plays is certainly there in Shakespeare. One difference between the Shakespeare play and the actual history is the circumstance of the death of Arthur - Shakespeare has Arthur die jumping from the castle walls, whereas many historians believe that Arthur was actually killed, possibly by John himself. The play takes as it's subject a previous dispute between Rome and the English ruler: the only English monarchs to be excommunicated were Harold II, John, Henry VIII and Elizabeth I. The choice of John for a monarch in conflict with Rome is therefore forced on Shakespeare, which is somewhat unfortunate given that both Henry VIII and John consolidated their position through the death of an Arthur with a better claim to the throne.

A Midsummer Nights Dream (1595)

The rude mechanicals of Shakespeare's "A Midsummer Night’s Dream" may be a comic rendition of the artisan actors of the provincial mystery plays, including the talking ass of Balaam in the Chester Mystery Plays. It has been claimed that William Shakespeare wrote A Midsummer Night's Dream for the occasion of the 1595 wedding of Elizabeth de Vere and William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby. Elizabeth de Vere, Countess of Derby, Lord of Mann (2 July 1575 – 10 March 1627), was an English noblewoman and the eldest daughter of the Elizabethan courtier, poet, and playwright Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford. Others have theorised that the play might have been written for a different aristocratic wedding (for example that of Thomas Berkeley and Elizabeth Carey), while yet others suggest that it was written for the Queen to celebrate the feast day of St. John (midsummer), but no evidence exists to support this theory.

Merry Wives of Windsor (c. 1597)

The earliest mention of Herne the Hunter comes from William Shakespeare's 1597 play The Merry Wives of Windsor. Officially published versions of the play refer only to the tale of Herne as the ghost of a former Windsor Forest keeper who haunts a particular oak tree at midnight in the winter time, the god of vegetation, vine, and the wild hunt, and is associated with the stag in rut each fall. The only link to the mystery plays is the reference to a "nut-hook" which is used in the sense that a beadle has a "catchpole". This may well have been a term in common usage.

Henry IV (c 1597)

The action of the Henriad follows the dynastic, cultural and psychological journey that England traveled as it left the medieval world with Richard II and moved on to Henry V and the Renaissance. Politically and socially the Henriad represents a progression from the heavy government of feudalism and hierarchy to the national state and scope for individualism. Alvin Kernan suggeted that in mythical terms it is "the passage is from a garden world to a fallen world". While that metaphor might be seen as linking it to the mystery plays it is a very common one and cannot be taken as establishing a link. John of Lancaster is represented in the play as the King's second son, although he was actually the third. The play includes the Battle of Shrewsbury in mid-1403, prior to which Hotspur had rallied his forces at Chester. While Hotspur and Prince Hal were both at the battle Shakespeare's portrayal of Hal slaying Hotspur is dramatic fiction. Hotspur had been one of Hal’s early mentors. In the first few years after the usurpation of Richard II, Hotspur had been made Constable of Chester, Flint, Conwy, and Caernarfon castles. Hal was put under his tutelage at Chester.

Hamlet (c 1600)

“Art thou there, truepenny?” is Hamlet’s question, directed at the “old mole” of a ghost in the understage cellarage of the Globe Theater, raises a question of the play: what is there, under the stage — Purgatory or Hell? This may have been based on the two-level wagons of the mystery plays. The portrayal of Herod was so "over-the-top" that it may have been referenced by Shakespeare in Hamlet (act 3, scene 2) where he mockingly coins the phrase "to out-Herod Herod" as an admonition to the players in the "play within the play":

- O, it offends me to the soul to hear a robustious periwig-pated fellow tear a passion to tatters, to very rags, to split the ears of the groundlings, who for the most part are capable of nothing but inexplicable dumbshows and noise: I would have such a fellow whipped for o'erdoing Termagant; it out-herods Herod: pray you, avoid it.

Shakespeare used the same construction elsewhere: "All's Well that Ends Well" has "out-villain'd villany". The figure of Herod and his traditional "over-acting" appears in other Mystery Play cycles and is not unique to Chester, and in many of these Herod all but begs for vocal opposition from the crowd, repeatedly daring any who are present to heckle and challenge him.

Twelfth Night, or What You Will (c 1600/1)

The play is believed to have drawn extensively on the Italian production Gl'ingannati (or The Deceived Ones), collectively written by the Accademia degli Intronati of Siena in 1531. It is conjectured that the name of its male lead, Orsino, was suggested by Virginio Orsini, Duke of Bracciano, an Italian nobleman who visited London in the winter of 1600 to 1601. "Twelfth Night" is a reference to the twelfth night after Christmas Day, also called the Eve of the Feast of Epiphany. It was originally a Catholic holiday, and these were sometimes occasions for revelry, like other Christian feast days. Servants often dressed up as their masters, men as women, and so forth. This history of festive ritual and carnivalesque reversal, is the cultural origin of the play's gender-confusion-driven plot. The Epiphany celebrations were often opposed by Puritans, much as Malvolio opposes the revelry in the play.

Twelfth night has a connection with Chester as being the date of the Epiphany Rising (1400) in support of Richard II. William Chaderton, Bishop of Chester (who also was Warden of Manchester College before John Dee, a particularly warmly regarded client or associate of the 6th Earl of Derby), sat at the ecclesiastical commission's quarterly sessions with the 4th Earl of Derby and was a close family friend of both Henry and Ferdinando Stanley: he preached to the 4th Earl's household seven times in 1587-90 (including during the Twelfth Night celebrations of 28th December 1588 to 17th January 1588/9, the day after "the Plaiers plaied" (obviously not Twelfth Night?).

MacBeth (c. 1606)

Shakespeare's porter from MacBeth says: "Knock, knock, knock!" - pretending he’s the gatekeeper in hell - "who’s there, in the devil’s name"? This is straight from the Harrowing of Hell in the Mystery Plays. Even more so because MacDuff (who was knocking) will be the eventual agent of MacBeth's destruction. In Macbeth Shakespeare portrays the sibylline figures from his source texts but transforms them into demonic figures - making them a parody of the Sibyll who advises Octavian in the Nativity play. Shakespeare acknowledges the power of prophecy to influence dynastic change, but shares the growing anxiety about prophesy in English culture. It is noted the Chester Plays contain significant references to prophecy. "By the pricking of my thumbs" occurs in the speech of the second witch, while the fourth boy in the "Shepherds" hands over a crozier-like "nut-hook" so that "Joseph shall not need to hurte his thumbs". The play features the murder of an innocent after the manner of Herod. Notably there is no suggestion that MacBeth has any children which might continue his line and at the outset of the play the Three Witches make no mention of his offspring (although they do mention those of Banquo).

The "Derbyites"

The "Shakespeare" canditdate most closely associated with Chester is William Stanley. So this section takes a closer look at him and the connections.

William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby, KG (1561 – 29 September 1642) was an English nobleman and politician. Stanley inherited a prominent social position that was both dangerous and unstable, as his mother was heir to Queen Elizabeth I under the Third Succession Act, a position inherited in 1596 by his deceased brother's oldest daughter, Anne, two years after William had inherited the Earldom from his brother Ferdinando Stanley, 5th Earl of Derby.

Ferdinando Stanley

Ferdinando Stanley, 5th Earl of Derby (1559 – 16 April 1594) was a supporter of the arts, enjoying music, dance, poetry, and singing, but above all he loved the theatre. He was the patron of many writers, including Robert Greene, Christopher Marlowe, Edmund Spenser, and William Shakespeare. Shakespeare may have been employed by Strange in his early years as one of Lord Strange's Men, when this troupe of acrobats and tumblers was reorganized, emphasizing the performing of plays. The troupe produced Titus Andronicus and the trilogy of Henry VI, Part 1, Henry VI, Part 2, and Henry VI, Part 3. Some of these plays may contain oblique references to the Stanley family's political position at the time. By 1590, Strange's was allied with the Admiral's Men, performing at The Theatre (owned by James Burbage, father of Richard Burbage). He was also associated with Leasowe Castle.

After his succession to his father's titles and estates in 1591, more reports of Roman Catholic plots on Ferdinando's behalf reached Burghley, particularly of a priest in Rome who had said of the new Earl of Derby that he "though he were of no religion, should find friends to decide a nearer estate [to the throne]". English rebels who had fled overseas sent a man named Richard Hesketh to urge Ferdinando that he had a claim to the crown of England by right of his descent from Mary, Queen Dowager of France, the second surviving daughter of Henry VII and a younger sister of Henry VIII. The Heskeths had once been retainers of the Stanley family and were also family friends (they also had links with Shakespeare). This is why Richard Hesketh was chosen to approach Derby about the matter that has come to be known as "the Hesketh Plot". Hesketh was an amateur alchemist and an aquaintance of both John Dee and Edward Kelly (both supposed alchemists). He was also Ferdinando's step-brother.

Ferdinando held two private meetings with Hesketh and then took him to London for further discussions with his mother, who had earlier been excluded from the Queen's court and placed under house-arrest for allegedly plotting against Elizabeth (by having a horoscope prepared to see when the queen would die - the astrologer got the axe). However, he finally dramatically rejected Hesketh's proposition with displays of scorn and indignation, even turning him over to Burghley (despite the fact that he had been told that should he not join the plot he would suffer a wretched death). Hesketh was interrogated and later executed at St Albans in November 1593 having implicated Ferdinando’s brother William in the plot. However, Stanley, who had hoped that his display of loyalty to Elizabeth would be rewarded, was shut out of the case and was marginalised. He was dismayed when the position of Lord Chamberlain of Chester was given to Thomas Egerton rather than himself, complaining that he was "crossed in court and crossed in his country". To add to the chaos several of Ferdinado’s servants had sought shelter in the household of the Earl of Essex after Hesketh's death and there was a suggestion that Essex also had a hand in Ferdinando’s soon to come demise.

Leasowe Castle may have been built for Ferdinando Stanley in 1593, possibly (though this is disputed) as an observation platform for the Wallasey races which took place on the sands in the 16th and 17th centuries, and which are regarded as a forerunner of the Derby races. Ferdinando's brother William was described as a noted sportsman and is remembered as a keen supporter of the Wallasey races. At first the castle consisted only of an octagonal tower. This had become disused by 1700, and it became known as "Mockbeggar Hall", a term often used for an ornate but derelict building: the term "Mockbeggar Wharf" is still used for the adjoining foreshore.

Ferdinando died in unexplained circumstances on 16th April 1594 having been taken suddenly and severely ill with vomiting. He is buried in Ormskirk. According to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography he asked his doctors to stop treating him as he knew he was dying (or perhaps because the treatments of his doctors were worse than the prospect of death). Due to the sudden and violent nature of his final illness, poisoning was widely suspected. He died what contemporaries considered a horrible death, in a "violent sea of vomit that was so putrified that no one would go near the body ‘till his burial". In Camden's Historie of Elizabeth (London: Fisher, 1630, Booke 4, p 65) it is stated:

- "Ferdinand Stanley Earle of Darby… expired in the flowre of his youth, not without suspition of poyson, being tormented with cruell paynes by frequent vomitings of a darke colour like rusty yron. There was found in his chamber an Image of waxe, the belly pierced thorow with haires of the same colour that his were, put there, (as the wiser sort have judged, to remove the suspition of poyson). The matter vomited up stayned the silver Basons in such sort, that by no art they could possibly be brought againe to their former brightnesse… No small suspicion lighted upon the Gentleman of his horse, who; as soone as the Earle tooke his bed, tooke his best horse, and fled".

It appears that the reference to silver may have been included to suggest that the poison was arsenic, as arsenic solutions will discolour silver. Arsenic was available at the time: during the Elizabethan era, some women used a mixture of vinegar, chalk, and arsenic applied topically to whiten their skin. This use of arsenic was intended to prevent aging and creasing of the skin. However extreme thirst is also a symptom of arsenical poisoning and not found among Ferdinando's meticulously recorded symptoms. When he became ill he had just returned from four days of hunting and may have eaten poisonous mushrooms, which would also fit his symptoms, although they are rare at the time of year he died.

Had Ferdinando Stanley not died in 1594 then upon the death of his mother (1596) he would have been first in line of succession to Elizabeth (who died in 1603) and could have become King Ferdinando at the age of 44.

William Stanley in Chester

William Stanley was born in Canon Row, Westminster, and educated at St John's College, Oxford. In 1582 he travelled to the continent to study in university towns in France and may also have attended Henry of Navarre's academy at Nérac. In 1585 he returned home but was once more sent to Paris as part of an embassy to Henri III of France. In 1585, Henry Stanley, 4th Earl of Derby, had been appointed by Elizabeth I as ambassador to Henri III, to invest him with the Order of the Garter, a political act expressing the two nations' amity in the context of the changed power struggles of the Netherlands against Spain after the death of François de France, Duc d'Anjou et Alençon (Henri III's younger brother, heir to the French throne, a Huguenot supporter, and a suitor of Elizabeth I's), and the assassination of William I, Prince of Orange, in 1584. Accounts of the journey to Paris made by Derby; the permanent ambassador to France, Sir Edward Stafford; Derby's younger son, our William Stanley; and their two-hundred-strong entourage, and of the investiture itself, comprise descriptions of successive ceremonial performances marking the stages of their travel and the weeks of luxurious, glorifying festivity that took place around the actual investiture itself, a ceremony of the highest magnificence, on 18th February 1585.

William Stanley then remained on the continent for a further three years of personal travels before returning home once more. He may have been accompanied on his travels by the young John Donne. During his travels, William Stanley is said to have led an adventurous existence, being involved in duels and love affairs and travelling in disguise as a friar while in Italy. He is supposed to have also visited Egypt, where he fought and killed a tiger, then going on to Anatolia, where it is claimed he narrowly escaped being executed for insulting the prophet Mohammed; he was supposedly released because a Muslim noblewoman wanted to marry him. According to the story, he turned her down, travelling on to Moscow and then to Greenland, from where he returned to Europe in a whaling ship.

These colourful adventures are traceable to a popular ballad entitled "Sir William Stanley's Garland", which exaggerates his three years away from England to "twenty one years travels through most parts of the world". This was first written-down in 1800 and its contents published in 1801. There is no extant documentary evidence for these supposed adventures, but the stories were regularly repeated in 19th-century biographies of the sixth Earl. In fact, during the time of these supposed adventures William was engaged in a long dispute over the inheritance of Ferdinando's estate. Ferdinando had stipulated that his estate should not be devided and should not go to his brother. William was able to get around this because his grandfather had placed the Stanley estate in the hands of trustees, in 1570 for a term of sixty years.

On 26 January 1595, he married Elizabeth de Vere, daughter of Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, and Anne Cecil. Elizabeth's maternal grandparents were William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley, and his second wife Mildred Cooke. William Cecil (13 September 1520 – 4 August 1598) was an English statesman, the chief adviser of Queen Elizabeth I for most of her reign, twice Secretary of State (1550–1553 and 1558–1572) and Lord High Treasurer from 1572. Cecil is widely considered the most powerful men of his time. His tight control over the finances of the Crown, leadership of the Privy Council, and the creation of a capable intelligence service under the direction of Francis Walsingham made him the most important minister for the majority of Elizabeth's reign. Elizabeth de Vere had planned to marry Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton, but this was called-off in November 1594 meaning that the wedding to William Stanley was arranged rather quickly. In the early years of their marriage, the couple's relationship was tempestuous and there were persistent rumours that Elizabeth had had affairs with Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, and Walter Ralegh. The allegations concerning her relationship with Essex were particularly strong in 1596 and 1597. Whether there was any truth in the rumours remains unknown.

After his period of European travel, the long legal battle eventually consolidated William Stanley's social position. Nevertheless, he was careful to remain circumspect in national politics, devoting himself to administration and cultural projects. The upshot of the legal battle was a judgement that the Isle of Man, a possession of the 5th Earl, was forfeit to the Queen. However, the Queen ceded her right to it in recognition of the Stanley family's services. Stanley was granted Lathom and Knowsley, with other lands and estates in Lancashire, Cumberland, Yorkshire, Cheshire (Bidston Hall on the Wirral), Wales, and elsewhere, while Ferdinando's daughters received estates linked to baronies and the Isle of Man, but they sold it to their uncle, the 6th Earl, and his title to it was later confirmed by James I. The costs of the battles and settlements in 1594-1610 was to be of permanent damage to the economic fortunes of the Stanleys.

A few years after the death of his wife (she died in 1627), when Derby was "old and infirm, and desirous of withdrawing himself from the hurry and fatigue of life" he assigned his estates to his son James, retaining an annuity of £1,000. He bought a house by the River Dee just outside Chester, where he lived in retirement until his death on 29 September 1642. It is now sometimes believed to be the structure known as "Stanley Palace", but may actually have been on the groves "by the River Dee just outside Chester" where he established a bowling green (see below). The minutes of the Chester Assembly for Friday, 22nd September 1626 record:

- "William Earl of Derby petitioned to have in fee farm a piece of land by Deeside underneath St. John's on which he had built a chamber and enclosed the land. It was ordered that he should be granted his request on payment of 20s. a year rent at Michaelmas"

Notably, this date is close to the time when William Stanley's wife died (1627).

The riverside below St. John's church was corporation property and used as a public walk by 1717. In 1726 it was leased by the city council to Charles Croughton, an apothecary (under yearly rent of one pepper corn), who secured the river bank and planted an avenue of trees for the public benefit. Croughton had lately purchased the "Earl of Derby's house and garden near Dee" and wanted a grant of the ground between his garden wall and the river Dee in return. The petition is ZAF/51/109 in the archives:

- "Petition from Charles Croughton, apothecary, stating that he had lately purchased the late Earl of Derby's house and garden near Deeside within the liberties of the city and praying a grant of the ground between his garden wall and the river Dee leaving a convenient footway through the same or, otherwise, liberty to bring his said garden wall in a direct line from the Bowling Green wall to the corner of the wall of the house of Easemont (sic) at the east end of his garden wall."

The wording of the lease was:

- "Herbage and pasture of piece of ground near St. John's Church, beside the River Dee, from the corner of the Bowling Green house to the garden wall, now in possession of Andrew Kendrick, 187 yards long, with licence for Croughton to carry his garden wall on the north side of the said ground in a direct line from his summer house wall to the house of easement at the east end of the said ground. Croughton to make a fit public walk from north to south 7 yards by 2 yards and plant it with trees and not to enclose it at each end except with a turnpike"

The "bowling green house" was next to the bowling green which Stanley had set out.

Conflicting Evidence

There is conflicting evidence as to where William lived. Both the following are from Bagley, J.J. The Earls of Derby. Sidgwick & Jackson, 1985, pp. 76 and 71.:

- "His house in Watergate was something of a literary and musical centre: in 1624 he allowed Francis Pilkington of Chester to include in his book of madrigals a pavan - a slow, stately dance—which he, William, had composed for the orpharion, an instrument resembling a large lute. Other members of his family did not burn with the enthusiasm which William showed for everything to do with the stage, but they were not necessarily uninterested."

Francis Pilkington (ca. 1565 – 1638) was an English classical composer, lutenist and singer, of the Renaissance and Baroque period. Pilkington received a B.Mus. degree from Oxford in 1595. In 1602 he became a singing man at Chester Cathedral and spent the rest of his life serving the cathedral. He became a minor canon in 1612, took holy orders in 1614 and was named precentor of the cathedral in 1623. Although he was a churchman, Pilkington composed largely secular music.

- "By the time Charles I had succeeded to the throne in 1625, Earl William had virtually retired to Bidston and his Chester home, Stanley House in Watergate. He had no wish to concern himself with the tensions developing between the King and his people. He preferred to read and write, watch plays, and listen to music."

Bidston Hall appears to have been rebuilt by William Stanley in 1620-21. Two letters from the Earl to the Council, dated respectively 9 August 1622 and 12 October 1623, show that he was then living at Bidston Hall at least part of the time.

Again in the Assembly records there is a mention of William Stanley being active in Chester from Friday, 2nd March 1609/10:

- "At the invitation of Hugh Glaseour, esquire, and Thomas Gamull, Recorder, the Assembly unanimously elected William, Earl of Derby, Knight of the Garter, and Chamberlain of the County Palatine of Chester, alderman in the place of Robert Wall, deceased. It was also agreed that the Earl should first be admitted a freeman of the City."

In 1612 he is wanting to lease land near St John's lane, and he was active as the Lord Lieutenant of Cheshire and Lancashire, from 1607–1642 and as the Vice-Admiral of Cheshire and Lancashire 1607–1638. None of this suggests someone who is seeking a quiet retirement following the death of his wife. As to where he was living in Chester at the time this is something of a puzzle. Stanley Palace was built in 1591 for lawyer Sir Peter Warburton of Grafton, Vice Chancellor of the Cheshire Exchequer and then the city's MP (and also - a relation to the bread bakers). In later life Warburton moved to Grafton Hall (demolished 1963) near Tilston. When Warburton died in 1621, the Chester property was inherited by his (sixth) daughter; Elizabeth, who was married to Sir Thomas Stanley, a kinsman of the earls of Derby (hence, some state, it is also known as Derby House) but in a separate branch of the family to William Stanley, but he died on 21 November 1605 at age 28 - before the death of Peter Warburton. On the death of her husband Elizabeth married Sir Richard Grosvenor of Eaton Hall (his third wife), she died in 1627 at her "Blackfriars home" (probably Stanley Palace, but also possibly "Black Hall" which was close to Stanley Palace). Sources agree that the house then passed to his son another Sir Thomas Stanley, 1st Bt. who was born on 31 May 1597. He held the office of Sheriff of Cheshire from 1630 to 1631 and was created 1st Baronet Stanley, of Alderley on 25 June 1660. His ancestor was John Stanley, a brother of the William and Thomas Stanleys present at the battle of Bosworth field. It is perhaps just possible that while Warburton built and owned Stanley Palace, he did not actually live there but leased it out.

James H. Greenstreet

William Stanley is one of several individuals who have been claimed by proponents of the Shakespearean authorship question to be the true author of William Shakespeare's works. Stanley's candidacy was first proposed in 1891 by the archivist James H. Greenstreet, who identified a pair of letters by the Jesuit spy George Fenner dating from 1599 in which he reported that Stanley was unlikely to advance the Roman Catholic cause, as he was "busy penning plays for the common players". Greenstreet argued that the comic scenes in Love's Labour's Lost were influenced by a pageant of the Nine Worthies "only ever performed in Stanley's home town of Chester" (he lived at Bidston Hall on the Wirral). A description of this survives from 1621 in the Cooper's records:

- "Order of our showe: First 2 woodmen with &c / St George fighting with ye dragon &c / (confused passage) / The 9 worthies in complete armour with crowns of gold on their heads / every one having his esquire to bear before him shield and penon of arms, dressed according to their lands were accustomed to be: 3 Israelites, 3 Infidels, 3 Christians &c / After them same to declare the rare virtues and noble deeds of the 9 worthy women / The 9 worthy women every one adorned after their country fashion, each one having her page before her bearing their armes."

This is not to say that the "Nine Worthies" were unknown prior to the pageant. They were first described in the early fourteenth century, by Jacques de Longuyon in his Voeux du Paon (1312). Greenstreet is arguing that they had only appeared in England in pageants at Chester.