Stuart Chester

This is part of a series of articles on the history of Chester through time:

-

Stuart Chester and the Civil War

The Stuart period of British history lasted from 1603 to 1714 during the dynasty of the House of Stuart. The period ended with the death of Queen Anne and the accession of King George I from the German House of Hanover. After the loss of the throne, the descendants of James VII and II came to be known as the Jacobites and continued for several generations to attempt to reclaim the English (and later British) throne as the rightful heirs.

The Stuart period was plagued by internal and religious strife including a period of Civil War which had a particular impact on Chester. Many of these internal conflicts were between the Crown and Parliament and their causes have been the subject of much historical debate, especially in the 20th Century when the debate was dubbed the "Storm over the gentry". The modern consensus are that the conflicts had a variety of causes, some arising out of the preceeding Tudor period (see: Tudor Chester) and some being down to the personalities of those in Stuart times. Causes varied dependent on location and the course of the Civil War in Chester was probably significantly influenced by local factors as well as national ones. It is possible that events in Chester had some minor effect of the slide into Civil War but the events mentioned below are noted more as local illustrations of causes that were also active elsewhere. During the long life of Roger Whitley (?1618-97) Chester changed from a City largely ignored by a distant royal earl, and thus run by a somewhat corrupt Corporation controlled by the guilds and burghers, to a City dominated by the local landed gentry, the Grosvenors. Pike and musket warfare gave way to rather more mobile warfare with the simple invention of the bayonet, and by Whitley's death Britain was at the eve of the Industrial Revolution.

Despite defeating the Spanish Armada in 1588, England faced ongoing difficulties. The economy was hit by a series of poor harvests and there was a heavy tax burden to support the wars with Spain and in Ireland. There was a major famine in Chester in 1598. The population increased and demand drove prices up while wages fell. The Spanish war affected trade in Chester and much business shifted to the French ports, but there were losses of ships due to the war and growth began to slow. The important wool export trade declined. A noted feature of the economy were monopolies, where the right to trade in certain goods was only granted to particular parties, often in return for a payment. These were a royal prerogative and a valuable source of income for the crown as well as a way of rewarding courtiers. They were not a new innovation but their grant expanded in the latter part of Elizabeths reign. A related economic practice was "fee farming", where the state reassigned the burden of tax collection to private individuals or groups. The recipient of the rights then paid the taxes or other fees for a certain area and for a certain period of time and attempted to cover their outlay by collecting money or saleable goods. The advantage to the state was that monies could be secured without the burden of collecting them. The benefit to the "farmer" would be the right to keep any excess that was collected.

Monopolies engendered a widespread sense of grievance and became a major subject of Parliamentary debate towards the end of the reign of Elizabeth, but she was able to deal with the matter with her usual knack of timely intervention, charm and an outward show of making concessions. In her famous "Golden Speech" of 30 November 1601 at Whitehall Palace to a deputation of 140 members, Elizabeth professed ignorance of the abuses, and won the members over with promises and her usual appeal to the emotions in what was a masterful oration. Sixteen months later she was dead.

Elizabeth would never name her successor. James Stuart was the son of Mary, Queen of Scots, and a great-great-grandson of Henry VII, King of England and Lord of Ireland, and thus a potential successor to all three thrones. From 1601, in the last years of Elizabeth's life, certain English politicians — notably her chief minister Sir Robert Cecil — maintained a secret correspondence with James to prepare in advance for a smooth succession. Elizabeth died in the early hours of 24 March 1603, and James was proclaimed king in London later the same day, without any opposition. His English coronation took place on 25 July 1603, with elaborate allegories provided by dramatic poets such as Thomas Dekker and Ben Jonson. However, an outbreak of plague restricted festivities, the goverment had debts of £400,000, and James had a very different approach to Parliament than Elizabeth.

In the early years of James's reign, the day-to-day running of the government was tightly managed by the shrewd Cecil, later Earl of Salisbury, ably assisted by the experienced Thomas Egerton, whom James made Baron Ellesmere and Lord Chancellor. Thomas Egerton was born in 1540 in the parish of Dodleston, Cheshire, England. He was the illegitimate son of Sir Richard Egerton and an unmarried woman named Alice Sparks from Bickerton. He bought Tatton Park, in 1598. It would stay in the family for more than three centuries. His third wife was Alice Spencer, whose first husband had been Ferdinando Stanley, 5th Earl of Derby (the one in line for the throne, who was probably murdered). The Egertons would have a significant impact on the history of Chester. Thomas Egerton (1540 – 15 March 1617) had a plot at the end of Whitefriars flattened and built what was apparently one of the finest mansions in the city. Egerton was made Chamberlain of Chester in 1593 and is associated with the traditional (but false) legend of how Gallantry Bank at Bickerton got its name.

The transition between the Tudor and Stuart periods roughly co-incides with a significant change in military technology: around 1600 the use of massed firearms emerged (see: Militia) as a replacement for archers. Producing an effective arquebusier required much less training than producing an effective bowman. Archers needed to build and train the right muscles. Most archers spent their whole lives training to shoot with accuracy, but with drill and instruction, the arquebusier was able to learn his profession in months as opposed to years and using them did not need continuously trained strength. This low level of skill made it a lot easier to outfit an army in a short amount of time as well as expand the small arms ranks. This idea of lower skilled, lightly armoured units was the driving force in the infantry revolution that soon took place and allowed infantries to phase out the longbow. An arquebusier could carry more ammunition and powder than a crossbowman or longbowman could with bolts or arrows. Once the methods were developed, powder and shot were relatively easy to mass-produce, while arrow making was a genuine craft requiring highly skilled labor. Ultimately, the arquebus became the dominant projectile weapon because it was easier to mass-produce and easier to train unskilled soldiers in its use. As musket technology evolved, the flaws of the musket became less frequent and the bow became irrelevant.

Chester in 1603

At the time of the accession of James I Chester had other concerns: there was a plague running riot in the city. There was a plague in London at the same time with at least 30,000 dead in 1603. This was part of the second plague Pandemic, a major series of epidemics of plague that started with the Black Death, which reached Europe in 1348 and killed up to a half of the population of Eurasia in the next four years. Although the plague died out in most places, it became endemic and recurred regularly. A series of major epidemics occurred in the late 17th century, and the disease recurred in some places until the late 18th century or the early 19th century. The plague which heralded the accession of the Stuart rulers actually reached Chester in September, 1602, in a glover’s (or musician's) house in St John Street (then Lane), where seven died, and kept increasing until the weekly deaths reached sixty. This particular plague cycle may well have been associated with the movement of troops through Chester in support of the Irish wars and the famines of the past years. War, famine and pestilence being known as companions. This did not stop some ascribing the plague to the accession of king James, or associating it with Kepler's Supernova.

These were not the only superstitions of the times. While king of Scotland, James VI became utterly convinced about the reality of witchcraft and its great danger to him, leading to the North Berwick witch trials that began in 1590. James was convinced that a coven of powerful witches was conspiring to murder him through magic, and that they were in league with the Devil. In 1597, with the end of the trials, James published his study of witchcraft, "Daemonologie". Shortly after becoming king of England he passed his "Act against Conjuration, Witchcraft and dealing with evil and wicked spirits". Sir Thomas Browne, who has links with Chester, would become involved in the subject in 1662 and his legal analysis would later be used at the Salem Witch Trials. Witch Trials would last almost to the end of the Stuart period - in 1712, Queen Anne pardoned Jane Wenham who had been sentenced to death for witchcraft, which served as a signal to the authorities that prosecution for such "crimes" should be ceased (the last witch execution was Mary Hicks in 1716).

Various theories have been put forward for the reasons for the "European Witch Craze". For many years the supposed explanation was either the climatic disturbance of the "Little Ice Age" or the outbreaks of various Pandemics - with "witches" being the convenient scapegoat. A more recent proposal is that "witch-hunting" was an activity intended to attract the loyalty of undecided christians during the reformation and counter-reformation. Protestants in general also tended to be more wary of witches: Luther himself authorized the execution of four accused witches, while Calvin urged Genevan officials to wipe out "the race of witches".

The widespread and severe epidemic of bubonic plague in 1603-5 was unusual in Chester in falling into two contrasting phases. The first was long drawn out but relatively mild: 933 dead out of c. 5,220 inhabitants over 83 weeks represented a death rate of 11 per cent a year, four times the annual rate of the previous decade but not as severe as that experienced elsewhere. The second phase killed 1,041 people in 34 weeks, or 20 per cent a year among a population probably as large as in 1603. The first outbreak was accompanied by 'other diseases' (probably smallpox), and when it was carried from Chester to Nantwich in June 1604 it killed 430 people in ten months, a mortality of between 23 and 28 per cent. Preventive measures taken in Chester by the Assembly in 1603-5 may have retarded the spread of infection, even though they were conventional and crude: erecting pesthouses on the outskirts to isolate the sick; destruction of infected bedding; orders against overcrowded housing; and a ban on the Michaelmas fair and Christmas watch in 1604 to prevent crowds from gathering. Some citizens, notably those who were part of the local government, seem to have flouted quarantine measures: former mayor John Aldersey, for example, was moved from Eastgate Street to Watergate Street while sick and later died of the plague. Richer citizens, perhaps more worried about the state of their businesses after the first phase than about the disease itself, may have delayed flight too long. William Aldersey, another former mayor, left only when the weekly death-toll reached 58 and his next-door neighbour's family had been almost wiped-out.

In the early seventeenth century Chester’s population within the city walls numbered around 5,000. The local economy revolved around the leather industry (see: Tanning), whose craftsmen comprised approximately 23 per cent of the freemen. Most trade was with Ireland, particularly Dublin. Some links with the Baltic developed during the period, but these were sporadic and did not involve large cargoes. Overseas trade was restricted to members of the city’s powerful Merchant Adventurers’ Company, founded in 1554. Despite being the dominant port in north-west England, Chester, or rather its corporation, was not wealthy. Rents from city lands, freemen admissions, and fees for grazing cattle on the Roodee accounted for under £100 p.a. Overall income ranged from between £283 in 1607-8 to just £130 in 1616-17. Chester’s poverty meant that corporation members were often surcharged to meet extraordinary expenses.

John Speed's map of Chester from 1610 shows the city with development along the main street frontages but still much open space. The Watertower now stands clear of the river. Speed, who was from Farndon, himself describes Chester as follows:

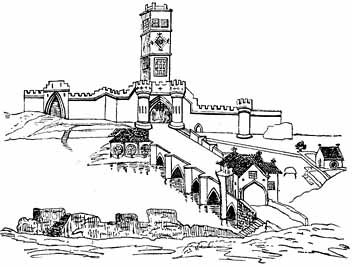

- "Over Deva or Dee a fair stone-bridge leadeth, built up on eight arches, at either end whereof is a Gate, from whence in a long Quadren-wise the walls do incompass the city, high and strongly built, with four faire Gates opening into the four winds, besides three Posterns and seven Watch-Towers extending in compass 1940 paces. On the south of this city is mounted a strong and stately Castle, round in form, and the base Court likewise inclosed with a circular wall. It hath been accounted the Key to Ireland, and great pity it is that the Port should decay as it daily doth, the sea being stopped to scour the River by a Causey that thwarteth Dee at her Bridge."

The "three posterns" are presumably the Shipgate, The Newgate and the Kaleyard Gate. Referring to the 1581 Braun and Hogenberg map, the "Seven Watch Towers" presumably include the Water-Tower, The Goblin Tower (now Pemberton's Parlour), the predecessor of Morgan's Mount, the Newton Tower (now the Phoenix Tower), the predecessor of Barnaby's Tower and the tower just to the east of the Watergate. However Braun and Hogenberg shows several other towers including the "Louse Tower" near the Shipgate and a then rather ruinous Bonewaldesthornes Tower.

Chester and Parliament

In the earlier part of the Tudor period Parliaments were occasional events and the power of parliament fell far short of being able to challenge the monarchy, but the power of parliament was growing. 1542 had seen the passage of the "Chester and Cheshire (Constituencies) Act" allowing the palatine county of Cheshire and the city to be represented in the Parliament of England. In Elizabethan times huge numbers of bills related to taxation and social/economic legislation. Many of these had consequences for Chester, who now had respresentation in Westminster and where the local power of the Palatinate was weakening. In 1559 alone eight statutes were passed concerning shoemakers, tanned leather, leather exports, wines, linen cloth, iron mills, English shipping, and the preservation of fish spawn, all of which would have a bearing on Chester. In 1554 a group of overseas traders associated with Chester had secured the incorporation by royal grant of a company of merchants, to be governed by a master and two wardens and enjoy the privileges normally granted to such companies. Membership was to comprise merchants trading with the Continent ("mere merchants") and exclude craftsmen and retailers. There was immediate opposition in Chester on the grounds that it would exclude some freemen from foreign trade contrary to long-established practice, but the company renewed its charter in 1559 and even came to include a few retailers. See Merchant Adventurers for more.

James I had clear ideas about the role of Parliament and did not shy away from stating them. In 1597–98, James wrote The True Law of Free Monarchies and Basilikon Doron (Royal Gift), in which he argues a theological basis for monarchy. In the "True Law", he sets out the "Divine Right of Kings", explaining that kings are higher beings than other men for Biblical reasons, though "the highest bench is the sliddriest to sit upon". The document proposes an absolutist theory of monarchy, by which a king may impose new laws by royal prerogative but must also pay heed to tradition and to God, who would "stirre up such scourges as pleaseth him, for punishment of wicked kings" - this was, in an ironic sense, a time of harvest failures and plagues. James's advice to his son Prince Henry Frederick concerning parliaments, which he understood as merely the king's "head court", foreshadows his difficulties with the English Commons: "Hold no Parliaments," he tells Henry, "but for the necesitie of new Lawes, which would be but seldome". On 7 July 1604, James had angrily prorogued Parliament after failing to win its support either for full union or financial subsidies. "I will not thank where I feel no thanks due", he had remarked in his closing speech. "... I am not of such a stock as to praise fools ... You see how many things you did not well ... I wish you would make use of your liberty with more modesty in time to come".

With the decline of the Palatinate Chester's governance was now not as isolated from Parliament as it had been previously and national politics soon infringed on local matters. In January 1606, king James attempted to have Hugh Mainwaring elected as Chester’s recorder, with the expectation that this would give him an MP "in his pocket". Hugh was presumably related to the MP Sir Arthur Mainwaring who was close to both James and Prince Henry Frederick. The corporation reminded the king that only the previous year he had confirmed the city’s charter, which gave Chester the right to elect its own recorder. Consequently, James decided "to forbear to press you any further in the suit". The election had been brought about by the unexpected death of senior recorder Thomas Lawton and, following the attempt at Royal intervention the new recorder, Thomas Gamull, was elected as MP in his place. Gamull had been MP for Chester previously. The Gamull's (see: Gamul House) were already becoming a major influence in Chester and would go on to play a significant part in the Civil War.

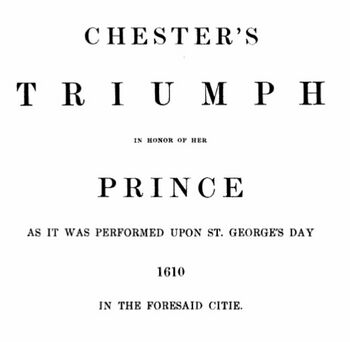

A New Earl and a Play for Chester (1610)

In 1610, with the confirmation of Prince Henry Frederick as Wales and Earl, Chester looked forward to the "return" of a prince and earl it had not really known since the visit of young Prince Arthur in 1499 (see: Cowper). For a century, since 1506, the City of Chester had been a county in its own right, effectively ruled by a Corporation which had the power to hold courts and to control trade, buildings and social conditions. From well before the death of Henry VIII in 1547, the nearest thing to an effective Earl was the Chamberlain, based at Chester Castle in the very center of the City, and the source of prolonged disputes over jusidiction with the Corporation. The institutions of the wider Palatinate were based at Chester Castle, but the markets of the City served as the mercantile center of the entire county. Those who made money by trade in and through the City invested in land in the countryside while rural men fought for civic positions. These conditions created a complex interplay between the City of Chester and the County of Cheshire as a whole. An Earl might have helped bridge this gap in the administration, and Henry Frederick was made Earl in 1610. He held several other "automatic" titles: Duke of Cornwall, Prince of Wales, Duke of Rothesay, Earl of Carrick, Baron of Renfrew, Lord of the Isles and Prince and Great Steward of Scotland. The young Earl was active in dancing, tennis, fencing and hunting. In 1607 Henry sought permission to learn to swim, but the Earls of Suffolk and Shrewsbury wrote to his tutor Newton that swimming was a "dangerous thing" that their own sons might practice "like feathers as light as things of nought", but was not suitable for Princes as "things of great weight and consequence". Perhaps it was meant as a jest, but became an ironic one. He was also much more marked in his Puritan tendencies than his father or younger brother Charles: in addition to the alms box to which Henry forced swearers to contribute, he made sure his household attended church services.

Certain of the citizens of Chester desired a visit from their young and energetic prince, and, as discussed in Chamber's Book of days they put on a pageant to attract him. One notable feature of the pageant was a play, or "Triumph", performed at the High Cross another was a celebration and races on the Roodee. A central figure in the "Triumph" was Mercury, god of financial gain, commerce, eloquence, messages, communication (including divination), travelers, boundaries, luck, trickery and thieves; he also serves as the guide of souls to the underworld. His name is possibly related to the Latin word merx ("merchandise"; cf. merchant, commerce, etc.). The temple of Mercury in Rome was regarded as a fitting place to worship a swift god of trade and travel, since it was a major center of commerce as well as a racetrack. In the pageant Mercury also symbolises the young Prince and starts his performance by showing due respect to the "high justice officer" (the Mayor).

It was not to be. The "coming man" did not come to Chester for the triumph in his honour. At the age of 18, the man who had been prepared for rulership all his life was taken ill after a swim in the Thames near his home at Richmond. His symptoms suggest he had water-borne typhoid fever, from which he died. As Henry's body was lowered into the ground, his chief servants broke their staves of office at the grave and an insane man ran naked through the mourners, yelling that he was the boy's ghost. His often sickly brother Charles eventually inherited the throne 13 years later, having had little of the preparation Henry had for the role but also inheriting his father's disdain for parliaments. Meanwhile the development of the Chester Militia echoed the emergence of the professional army, as a distinct political unit, which could and would later defy both Crown and parliament.

Iconoclasm in 1613

From the end of Elizabeth's reign and into that of James, the more extreme protestants became progressively more radicalised as Puritans. Clerical support for puritanism in Chester is not easy to measure. William Barlow, dean at the Cathedral in 1603-5, was a prominent and strongly anti-puritan member of the Hampton Court conference in 1604, but Bishop Richard Vaughan (1597-1604) sympathized with many puritan opinions. The next bishop, George Lloyd (1604-15), a former divinity lecturer at the Cathedral, was an active preacher and apparently a moderate who tolerated puritan clergy in Chester. Lloyd's portrain hangs in the "Puritan Room" at the Grosvenor Museum and his supposed residence, Bishop Lloyd's House, still exists in Watergate Street, but has been much altered over the years. His successor, Thomas Morton (1616-19), however, was of firmly Anglican views and pressed the Puritans to conform. His task was made more difficult by the ministrations of Nicholas Byfield, a Calvinist polemicist and a powerful preacher, who was rector of St Peter's 1608-15, where his congregation included the well known puritan gentleman John Bruen of Bruen Stapleford, a supporter of private prayer meetings in the parish. Byfield was educated at Exeter College, Oxford, but did not emerge with a degree. He intended to exercise his ministry in Ireland; but on his way there he preached at Chester, and was prevailed on to remain as one of the city preachers, without cure. His name is still displayed at St Peter among the list of past rectors on the wall near the font.

John Bruen (1560–1625) was an English Puritan layman, celebrated in his time for piety. In his youth he was the spoiled son of a very wealthy man. On the death of his father in 1587, Bruen's character changed completely. Thenceforth, Bruen was up every day at 3 or 4 a.m. and engaged in prayer and Bible study. Bruen prayed and read the Bible seven times each day. He destroyed his backgammon table by pitching it forcefully into the fireplace. He marred his deck of cards by tearing up the jacks (which were vital to play the local version of "Noddy") and proclaimed games to be the works of the devil and an idle mind. He made it a point to walk the one mile to church each Sunday, gathering the tenants of his properties and arriving in a large cluster for service. His charitable works were notable: he offered the homeless a place to sleep within his own home, the wool of his sheep provided clothing for the poor, the mutton their food. Corn from his fields fed those who came to his door for comfort.

On Ascension Eve (12th May) 1613 a small group of men broke down the roadside cross at "Viccars Crosse" and Christleton Churchyard Cross. This was but part of the iconoclastic cross-smashing that took place around Chester that year, including those in the churchyards of Barrow, Eccleston and Christleton. The Barrow cross possibly partly survives as the column of a sundial in St. Bartholomew's Churchyard. In the winter of 1613 seventeen of Bruen's students and servants were arrested for destroying roadside crosses in Cheshire. Seven of the vandals appeared before the Star Chamber in London. The outcome of the trial resulted in a 500 pound fine, an expense that Bruen covered for his followers. While those charged with the crime denied Bruen’s involvement, it was clear to all that the event was planned at one of his conventicles at Stapleford Hall. According to a complaint by John Savage (Lord of the Manor of Tarvin) in the Star Chamber records, these included four ancient crosses of squared stone eight feet high, one in Delamere Forest, another in Tarvin, another at Christleton, and Ecclestone Cross:

- "All of them beyond the memory of man, boundaries of townships and estates, and were also good direction points for travellers, and places appointed for the payment of certain rents, and for other lawful meetings".

It was Bruen himself, together with John Eaton & Hugh Jones who broke down "Viccars Crosse" and Christleton Churchyard Cross on Ascension Eve 1613. One of the crosses was restored in 2018.

Morton's successor as Bishop of Chester was Bishop Bridgeman (1619-1652) who was at first lenient towards puritans but initialised suspensions against the puritans Thomas Paget, John Angier and Samuel Eaton. Paget was later exiled to Amsterdam (where he lived off the profits of his family slave-trading). Angier was twice excommunicated. Easton, from Crowley near Great Budworth, eventually fled to New England. By the late 1630s, Puritans were in alliance with the growing commercial world, with the parliamentary opposition to the royal prerogative, and with the Scottish Presbyterians with whom they had much in common.

A Royal Visit (1616) and a Spanish Match

William Aldersey followed in his father's footsteps as a merchant ironmonger and so successful in overseas trade that he became a founding member of the East India Company in 1600, and is said to have been named in the patent incorporating the Company dated 31 December 1600 (although his name does not appear in available texts - he was more likely one of the 125 shareholders, rather than one of the 24 directors named in the patent). This proved to be an extremely lucrative investment, for although he had to subscribe £240 per share during 1601, the distributed profit on the first voyage by 1603 was nearly 300 per cent, and for all the East India voyages up to 1616 was never less than 220 per cent. Chester also provided the East India Company with the Middleton brothers, who played an important part in the early voyages.

Aldersey served as mayor of Chester in 1595–6 and 1613–4 and was particularly interested in the troops and horses which sailed from Chester to support the standing army in Ireland. Aldersey himself recorded the numbers and county of origin of the troops and horses dispatched between 1594 and 1616. It is said that his pride in this related to a "special barracks" he had built for that traffic, and to Chester’s efficiency in revictualing warships. The presence of so many troops also brought problems. Demands strained local markets, especially during the shortages of the later 1590s: prices rose, ships' masters demanded large payments, there were difficulties with the authorities of Liverpool, disaffected men deserted in droves and were rarely captured, weapons were often found to be defective, moneys were embezzled, profiteering was rife, and Chester earned a reputation as a "robber's cave". Disorderly conduct was frequent, especially when troops were delayed by bad weather or lack of ships. To contain it, in 1594 the mayor erected a gibbet at the High Cross. It may well be that Aldersey's interest in the origin of the troops, his "special barracks" etc. had less to do with any civic pride, and more to do with keeping the peace in the presence of a large number of frequently drunken and unruly troops. While the events mentioned above took place in the reign of Elizabeth they illustrate hom important Chester had become in communication with Ireland, as well as how important this communication was to the economy of Chester. See Chester and Ireland for more.

Between his work and his civic duties, Aldersey studied Chester's Roman archaeology and the documentation of its medieval re-emergence. He is particularly remembered for his compilation of a list of the past mayors of Chester. The list survives to this day in a badly damaged memorandum book which was handed down through the Leche family. Aldersey’s last honour was to attend a civic dinner when James I visited Chester in August 1616. As the most senior alderman, he presented the king with a gold "standing bowl" chock full of gold coins (100 Jacobins) on the city’s behalf. He records the event himself:

- "12 October 1616 - The Kinges maiesty Came the 23rd day of august to the Lea hall to Sir George Calueley and there had a banquet, and from thence the same day to the Citty of Chester, where he was banqueted in the pentice, and presented with a Cupp of gold by the Citty. and from thence went to Vale riall [word cancelled] the same night beinge Saturday where he rested till mondey, and then came to the nante wiche that night and so away." - ALDERSEY FAMILY COLLECTION CR 469.

The annalists of Vale Royal record the events as follows (one or other has the year wrong):

- "1617 On the 23d of August our city was graced with the royal presence of our sovereign King James who being attended with many honourable earls reverend bishops and worthy knights and courtiers besides all the gentry of the shire rode in state through the city being met with the sheriffs peers and common council of the city every one with his foot cloth well mounted on horseback. All the train soldiers of the city standing in order without the Eastgate and every company with their ensigns in seemly sort did keep their several stations on both sides of the Eastgate street. The mayor and all the aldermen took their places on a scaffold railed and hung about with green and there in most grave and seemly manner they attended the coming of his Majesty. At which time after a learned speech delivered by the recorder the mayor presented to the king a fair standing cup with a cover double gilt and therein an hundred jacobins of gold and likewise the mayor delivered the city's sword to the king who gave it to the mayor again. And the same was borne before the king by the mayor being on horseback The sword of state was borne by the Right Hon William Earl of Derby chief chamberlain of the county palatine of Chester. The king rode first to the minster where he alighted from his horse and in the west aisle of the minster be heard an oration delivered in Latin by a scholar of the free school after the said oration he went into the choir. And there in a seat made for the king in the higher end of the choir he heard an anthem sung. After certain prayers the king went from thence to the Pentice where a sumptuous banquet was prepared at the city's cost which being ended the king departed to the Vale Royal. And at his departure the order of knighthood was offered to Mr Mayor but he refused the same." (as quoted in Hemingway)

Leche House and the Spanish Match

At the time there was interest in a third "Spanish Match" - yet another attempt to improve relations with Spain by a royal marriage. James had quickly ended the expensive war with Spain that lasted from 1585 to 1604. The "Spanish Match" was a proposed marriage between Prince Charles (later king), the son of King James I of Great Britain, and Infanta Maria Anna of Spain, the daughter of Philip III of Spain. Of course, a previous "Spanish Match" had brought Catherine of Aragon to England and another had wed "Bloody" Mary to the deeply devout but flat broke Philip II of Spain making him jure uxoris King of England and Ireland. Negotiations about the wedding of Prince Charles took place over the period 1614 to 1623, and during this time became closely related to aspects of British foreign and religious policy. There was in fact no chance that Pope Paul V would have issued the required dispensation for the Infanta to marry a Protestant - a fact apparently well known to the Spanish king but of which the English negotiators were ignorant (it was also kept from the Spanish ambassador). Paul V died early in 1621, and his successor Pope Gregory XV was thought amenable to the idea of the match. However by the 1620's events on the continent stirred up anti-Catholic feeling to a new pitch. In fact there was so much discussion of the "Spanish Match" that on the 24th December 1620, King James issued a strongly worded proclamation to put a stop to it.

At about the time that these events were transpiring Leche House in Watergate Street was partly rebuilt and redecorated. The decorations contain some references which are often said to relate to Catherine of Aragon. There are (as Frank Simpson records):

- On the north side is a shield which, it is said, bore the arms of Catherine of Aragon, but nothing is to be seen on it at the present time. Above this is a smaller shield bearing a bull’s head with horns; on either side are flying horses, some scroll work, roses, and pomegranates. It is evident, therefore, that this decoration has reference to this Spanish princess, for she had for her badges the rose, a sheaf of arrows, and the pomegranate, the latter of which she introduced into this country.".

- "On the opposite side of the room the Tudor rose is very prominent, as also is a small shield containing a bull’s head, similar to that on the north side. This decoration evidently refers to King Henry VIII, who, it will be remembered, took for his first wife Catherine of Arragon, the young widow of his brother, Prince Arthur";

- ..."the Prince of Wales feathers, with P on the dexter, and C on the sinister side, the whole enclosed by the garter, with coronet above; and on either side a flaur-de-lys. The letters P and C appear to allude to Catherine...";

"P and C" could also be a reference to Prince Charles. The Leche House hardly hides the signs that something suspicious may have been going on there: it also features a reputed "priest hole" and a "squint", or spyhole which allows the lower hall to be viewed from an upper gallery. Given the dates the legend that Catherine of Aragon stayed there seems impossible to base on actual history, but the symbolism used in the redecoration may be a reference to the proposed marriage of Charles to Maria Anna. In 1623 Charles, accompanied by the utterly incompetent George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, actually visited Madrid to meet his intended bride and the matter ended in a farce. Wigs and false beards were obtained and off they went on a romantic if somewhat foolhardy journey. Buckingham's crassness and quarrel with the Count of Olivares, the Spanish chief minister, was apparently contributory to the total collapse of the proposed mariage agreement. Contempory accounts evidently give Olivares an 'extravagant, out-size personality with a gift for endless self-dramatisation'. The Infanta said she would rather go into a nunnery than marry Charles. And when a drunken Sir Edmund Verney punched a priest, the English party were requested to leave Spain. The Spanish ambassador asked Parliament to have Buckingham executed for his behaviour in Madrid, but Buckingham gained popularity by calling for war with Spain on his return. Charles later married the catholic Henrietta Maria the youngest daughter of Henry IV of France.

Grosvenors

A family which was later to dominate the politics of Chester now appears on the scene. Sir Richard Grosvenor, 1st Baronet (9 January 1585 – 14 September 1645) was born at Eaton Hall, Cheshire, the only surviving son of 17 children. His father was Richard Grosvenor of Eaton, and his mother was Christian, the daughter of Sir Richard Brooke of Norton Priory, Cheshire. Present-day baronets date from 1611 when James I granted letters patent to "200 gentlemen of good birth" with an income of at least £1,000 a year. In return for the honour, each was required to pay for the upkeep of thirty soldiers for three years amounting to £1,095, in those days a very large sum. Baronetcy is the only British hereditary honour that is not a peerage, and was used by James I as a way of raising cash.

At the age of ten Sir Richard joined the household of John Bruen of Stapleford, a "godly Protestant tutor to children of the local upper gentry", who emphasized the link between "magistracy and ministry", and was, as noted, above an extreme Puritan. At the age of 13 he went to Queen's College, Oxford, matriculated in 1599 and graduated BA on 30 June 1602 (aged 17). His tutor at Oxford was probably the Puritan William Hinde. Hinde became perpetual curate of Bunbury, Cheshire in about 1603. He was a leader of the nonconformists in Cheshire, and clashed with Thomas Morton (bishop of Chester). In 1602 Grosvenor also became High Sheriff of Cheshire. He was knighted by James I in Vale Royal on 24 August 1617. In 1620 he became MP for Cheshire as a "junior knight of the shire". He was created baronet on 23 February 1622. In 1623 he was again High Sheriff of Cheshire and 1n 1625 High Sheriff of Denbighshire. In 1626 he was removed from the bench, probably for having spoken out in Parliament against the king’s "favourite" (i.e. "toy-boy"), George Villiers, the duke of Buckingham, and for having presented the names of Buckingham's clients to the Common’s committee for recusant officeholders.

Richard Grosvenor was a firm believer in the "divine right of kingship" and in patriarchal authority, but at the same time he staunchly defended the liberties of the subject and of parliament's role as "the representative of the people". Above all, he was concerned to root out the "evil of popery" and to overcome the influence of "evil counsellors" close to the King (including Villiers).

Richard was involved in the lead industry in North Wales. In 1589 the Crown granted the mineral rights in the lordships of Coleshill and Rhuddlan (Halkyn Mountain forms part of this) to a William Ratcliffe of London. In 1597, the same William Ratcliffe was granted a lease of a lead smelting mill and a small plot of land called "Y Thole" by Edward Lloyd of Pentrehobin (indicating that the industry was already established). These two rights were then sold to Richard Grosvenor in 1601 and thus began the family's connection with lead mining. Around this time they also accumulated the mineral rights in the lordships of Bromfield and Yale in Denbighshire. These acquisitions enabled this family to control a huge swathe of the industry in the Mold area.

Taxation and Waterworks

"Prisage" was a toll paid to the Crown on certain goods, including wine. In Chester, the fee was due to the Earl. "Prisage" differed from "Custom" which at times was a toll paid by alien merchants. As with prisage the situation in Chester was complicated by the palatine nature of the county. Chester appears to have somehow obtained an excemption from prisage on wines. In 1605 Chester's exemption from "prisage" on imported wines was deemed to have ended, and competition ensued for the right to collect the tax. At first the corporation was allowed to farm it from the royal grantee (Sir Richard Bulkeley), with William Gamull and other prominent merchants as its subfarmers from 1611. In 1624 a new farmer of prisage instead sublet his rights for £650 a year exclusively to five major wine merchants, William and Andrew Gamull, William Aldersey, Thomas Thropp, and William Glegg.

The arrangement had been secured in secret and was challenged by William Edwards, a new councilman already embattled against Gamull's clique for preventing his admission to the Merchants' company. In 1629 the dispute took another twist when William Gamull and his friends, supposedly negotiating a renewal of the licence to export calfskins on behalf of the city generally, instead secured a monopoly for themselves. The privy council finally ruled that all merchants should benefit, though perhaps only on Gamull's terms. In 1630 Gamull and others were still allegedly refusing to allow Edwards to share in the freighting of ships, and two years later Edwards and his associates were accused of diverting cargoes of wine of Beaumaris in order to avoid paying prisage at Chester. Edwards's campaign seems to have won him support, however, for he became sheriff in 1627, an alderman in 1631 and was mayor in 1636-7. By 1640 conflict among the merchants within Chester had somewhat died down: the corporation had resumed the right to levy the prisage on wines, and negotiations for a new licence to export calfskins were conducted in the name of the mayor and citizens. The Merchants' company remained in being, with 46 members in 1639.

The Gamull's were also involved in a curious dispute involving the latest technology of the time. In 1632 Tyrer sold his interest in the Bridgegate Waterworks by the Old Dee Bridge to a consortium headed by Sir Randle Mainwaring (1367-1456), but a dispute with Francis Gamull, who controlled the Dee Mills and causeway, led to Gamull's cutting off the supply. In 1588 alderman Edmund Gamull, later mayor, had paid £600 in advance (according to some accounts) to renew the lease on the corm mills at the reduced rent of £100, but the family got off to a bad start: the weir is known to have collapsed at least once in 1601. The collapse of the weir was only the first of Gamul's problems. In 1607 some of the citizens, abetted by neighbouring gentry, proposed to demolish the weir to improve the tidal scour of the river, thereby ruining the corn and fulling mills and the waterworks. Another concern was that the weir caused water in the River Dee to back-up causing flooding upstream, but it is not clear whether this had been a problem long before the weir was constructed. Gamul was among those instrumental in ensuring that the Privy Council quashed the orders that a breach be made in the causeway. Commissioners who sat, originally decreed that one-third "of the said Weyre be pulled down and the river there made open" but this order was not carried out because an appeal to the Privy Council decided the Commissioners:

- "had no power to pull it down but only to abate it, if it had been enhanced"

Tyrer had leased the site of his waterworks from the Gamull family, and an arrangement was devised by which no premises could have water unless they purchased all their flour from the mill. The matter again went before the privy council who decided that Gamull must allow the supply to continue. These various attempts by the Gamulls to secore monopolies on trade caused rifts between the city and the county. In summary, the income of a major clique within the City Assembly was dependent on royal grants of rights and, while it did not always find in their favour, the decisions of the Privy Council.

James I dies

In his later years, James suffered increasingly from arthritis, gout and kidney stones. He also lost his teeth and drank heavily. The king was often seriously ill during 1625 the last year of his life, leaving him an increasingly peripheral figure, rarely able to visit London, while Villiers, who was probably his lover, consolidated his control of Charles to ensure his own future. In early 1625, James was plagued by severe attacks of arthritis, gout, and fainting fits, and fell seriously ill in March with tertian ague and then suffered a stroke. He died at Theobalds House on 27 March during a violent attack of dysentery, with Villiers at his bedside. James's funeral on 7 May was a magnificent but disorderly affair. Bishop John Williams of Lincoln preached the sermon, observing, "King Solomon died in Peace, when he had lived about sixty years ... and so you know did King James".

Under James, the Plantation of Ulster by English and Scots Protestants began, and the English colonisation of North America started its course with the foundation of Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607. According to a tradition originating with anti-Stuart historians of the mid-17th-century, James's taste for political absolutism, his financial irresponsibility, and his cultivation of unpopular favourites (including Villiers) established the foundations of the English Civil War. James also seems to have bequeathed Charles a belief in the divine right of kings, combined with a disdain for Parliament. James's plantation in Ireland would lead to conflict and savage repression and then a costly war.

Some historians have presented Charles inherited belief in the "divine right of Kings" and conflict with Parliament over money as the causes of the Civil War. Others have argued that the gentry, enriched by the disposal of the monastries, sought an increase in their freedom against the last remnants of feudalism. Yet others, would lay the blame upon the radicalisation of the Puritans and the rumours about Charles being a secret catholic. Events in and around Chester show that there were often local and personal disputes that could well have played a part in the slow drift to war.

Attitudes towards women appear to have continued to change in Chester. A scold's bridle is referred to in the book Three Men in a Boat by Jerome K. Jerome. This was one on display in the church of St Mary at Walton on Thames, joking that a shortage of iron, or possibly iron not being strong enough to curb a woman's tongue, was why it was no longer in use. In fact the original Walton bridle, which was stolen in 1965, was dated (it is not known how) to 1633 and came to the Parish in 1723, inscribed "Chester presents Walton with a bridle to curb women’s tongues which talk too idle". Local tradition in Walton (where the stolen bridle was soon reproduced) varies between the bridle or brank having come from Chester or having been donated by a person named Chester (who had lost an estate "through the instumentality of a gossipping, lying woman"). However, in 1858, an exhaustive study of "Cheshire branks" was carried out by Dr T. N. Brushfield (house surgeon to "Chester County Lunatic Asylum" - as it was then called) for a paper read before the Chester Archaeological Society. The subject-matter seems to have been of particular interest to a certain type of Victorian gentleman as illustrated by works such as "Bygone Punishments". Brushfield evidently concluded that the Walton bridle was indeed from Chester. The "scolds bridle" was also known as the "witches bridle" and is believed to have originated in Scotland around 1567.

The European "Witch Craze" seems to have reached Chester, where John Bradshaw had been appointed Chief Justice of Chester in 1649 in part recognition of his services as Lord President of the High Court which had tried and sentenced Charles I to death. Bradshaw had condemned to death three Cheshire women for "entertaining evil spirits and bewitching Elizabeth Furnivall, who had languished and died". They had been hanged at Boughton about 3 p.m. on Tuesday, 17 October 1654. A further three women were sentenced to death by the same judge at Chester in 1656 and were hanged at Boughton on 15 October. Bradshaw was himself to hang: on 30 January 1661 – the twelfth anniversary of the regicide – the bodies of John Bradshaw, Oliver Cromwell and Henry Ireton were ordered to be exhumed and displayed in chains all day on the gallows at Tyburn. At sunset, the three bodies that had been displayed publicly as those of the three judges being executed posthumously were all beheaded. The bodies were thrown into a common pit and the heads displayed on pikes at Westminster Hall. Whether Bradshaws body was actually one of those "executed" is not certain.

Charles I and The Road to War

Following a series of disputes with Parliament over granting taxes, in 1627 Charles I imposed "forced loans", and imprisoned those who refused to pay, without trial. This was followed in 1628 by the use of martial law, forcing private citizens to feed, clothe and accommodate soldiers and sailors, which implied the king could deprive any individual of property, or freedom, without justification. It united opposition at all levels of society, particularly those elements the monarchy depended on for financial support, collecting taxes, administering justice etc, since wealth simply increased vulnerability. In 1628, Charles I, having prorogued Parliament in early summer and after his assent to the Petition of Right, proceeded to levy ship money on every county in England without Parliament, issuing writs requiring £173,000 to be returned to the exchequer. Unsurprisingly, there were those who felt that there should be "no taxation without representation". This was not the only ancient law that Charles used to try to fill his coffers: in 1630, Charles I resurrected a medieval law that all gentlemen with an annual income of £40 at the time of his coronation and who had not asked to be knighted should be fined.

Mainwaring

The hapless Philip Mainwaring was a younger son of a Chester family who would expect little in the way of inheritance and therefore had to make his own way in the world. He started his career at the age of 16 in around 1605 and studied at Gray's Inn before graduating from Brasenose in 1610. He then entered into the service of Robert Cecil, earl of Salisbury, through his mother’s family – the Fittons’ – connections. Before the end of 1610 he was described as "my Lord Chancellor’s man", referring to Thomas Egerton, Lord Ellesmere, himself a Cheshire gentleman. During the latter part of that decade, probably after Ellesmere’s death in 1617, Mainwaring began working as an agent for Thomas Howard, earl of Arundel, at home and in the Netherlands, where he ran errands for the earl in Antwerp and Amsterdam. The errands included the purchase of artworks. Working for Arundel brought Mainwaring into close contact with a man who placed great emphasis on noble lineage and matters of honour and gentility. Arundel was on good terms with James I. Arundel favoured the "Spanish Match" and the failure of that and the accesssion of Charles brought a shift towards an anti-Spanish foreign policy and an immediate change for the worse in Arundel’s fortunes, and therefore in Mainwaring’s prospects. By the late 1620s Mainwaring had served a number of patrons, none of which had been able to advance him to office. Now aged forty, he must have been looking for a patron who might be better placed to further his career, and he had begun to communicate with Thomas Wentworth, President of the Council of the North, shortly to be appointed to the Privy Council, informing him of foreign developments and court news. Wentworth appears to have had some connections with Chester as in 1632 he stayed at the Bishops Palace and was entertained at the Pentice. Mainwaring’s services were finally rewarded in 1634 when the lord deputy secured his appointment as the Irish Secretary of State to replace the ageing Sir Dudley Norton. With this post came membership of the Irish privy council and a knighthood, and it was the highest administrative post held by a member of the Cheshire gentry at this time.

A curious connection between Chester and Wentworth is found in an event during Wentworth's tenure in Ireland. It was under his patronage that the Werburgh Street Theatre, Ireland's first theatre, was opened by John Ogilby, a member of his household, and survived for several years despite the opposition of Archbishop James Ussher of Armagh. James Shirley, the English dramatist, wrote several plays for it, one with a distinctively Irish theme, and Landgartha, by Henry Burnell, the first known play by an Irish dramatist, was produced there in 1640. Werburgh was the patron saint of Chester and the street in Dublin is named after St Werburgh's Church, originally built in 1178.

In favouring Philip Mainwaring, Wentworth went against the advice of his closest political allies, Archbishop Laud and Francis, Lord Cottington. Cottington reminded Wentworth that he had himself voiced criticisms of Mainwaring in the past. The Mainwarings were counted, along with the Bruens among the leading puritan families of Cheshire, which, alongside his close connection with Arundel, would not have commended him to Laud. Mainwaring's poor choice of sponsors revealed itself again in May 1641 when Parliament accused the king’s chief minister, Thomas Wentworth, Lord Strafford, of treason for his excesses in Ireland and executed him.

Mainwaring's role in the events in Ireland has not been well researched. He may have simply been a "hanger-on" or may, as Secretary of State, have taken a more active role in events. He was a fervent Royalist and imprisoned during the Civil War. After the Restoration of Charles II Mainwaring applied unsuccessfully for the position of headmaster of Charterhouse School. In December 1660, Mainwaring was again appointed to the Irish Privy Council. It was suggested that given his advanced years he should step down from his old office as Principal Secretary, but he held on firmly to his place. He was then elected MP for Newton in the Cavalier Parliament in 1661, but died later that year. He never married.

War

The 1639 and 1640 Bishops' Wars were the first of the conflicts known collectively as the 1638 to 1651 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which took place in Scotland, England and Ireland (separate kingdoms with the same king). Others include the Irish Confederate Wars, the First, Second and Third English Civil Wars, and the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland. The Bishops' Wars originated in disputes over governance of the Church of Scotland or kirk that began in the 1580s and came to a head when Charles I attempted to impose uniform practices on the Scots Kirk and the Church of England. In 1636, a new Book of Canons replaced John Knox's Book of Discipline and excommunicated anyone who denied the King's supremacy in church matters. These measures were opposed by most Scots, who supported a Presbyterian church governed by ministers and elders. The Scots sought support from sympathisers in Ireland and England, chiefly Puritans who objected to the religious reforms and those who wanted to force Charles to recall Parliament, suspended since 1629. The Scots then invaded England. The English army mustered at the border town of Berwick-upon-Tweed totalled some 15,000 men, but the vast majority were untrained conscripts from the Northern trained bands or militia, many armed only with bows and arrows. With the Scottish army in northeastern England, the Chester Assembly set up a nightly watch, strengthened the defences at the Eastgate, Newgate (todays Wolfgate), and Bridgegate, and ordered members of the corporation and others to supply corselets, muskets, halberds, and calivers within a month.

By late 1640, Charles had no money to continue his war and there was no option but to call a new Parliament and raise money to fund an army. The Long Parliament assembled on 3 November 1640, and Charles immediately summoned Strafford to London, promising that he "should not suffer in his person, honour or fortune". Parliament was concerned that if Charles was provided with the means to raise an army he would use it against them. One of Parliament's first utterances after its 11-year forced hiatus was to impeach Strafford for "high misdemeanours" regarding his conduct in Ireland. However tyrannical Strafford's earlier conduct may have been, his offence was outside the definition of high treason. Although a flood of complaints poured in from Ireland, and Strafford's many enemies there were happy to testify against him, none of them could point to any act which was treasonable, as opposed to high-handed. Impeachment failed, and the Commons, feeling their victim slipping from their grasp, brought in and passed a bill of attainder on 13 April by a vote of 204 to 59. Charles had a serious problem with signing Strafford's death warrant as a matter of conscience, especially as he had explicitly promised Stafford that, no matter what happened, he would not die. However, to refuse the will of the Parliament on this matter could seriously threaten the monarchy. Strafford now wrote releasing the King from his engagements and declaring his willingness to die to reconcile Charles to his subjects.

- "I do most humbly beseech you, for the preventing of such massacres as may happen by your refusal, to pass the bill; by this means to remove ... the unfortunate thing forth of the way towards that blessed agreement, which God, I trust, shall for ever establish between you and your subjects"

Whether Strafford was now resigned to death, which soon followed (12th May 1641), or whether he thought that the letter, if circulated, might move his enemies to mercy, is still debated. Strafford's administration had improved the Irish economy and boosted tax revenue, but had done so by heavy-handedly imposing order. A series of alarmist pamphlets published stories of atrocities in Ireland, which included massacres of New English settlers by the native Irish who could not be controlled by the Old English lords. When rumours reached Charles that Parliament intended to impeach his wife for supposedly conspiring with the Irish rebels, the king decided to take drastic action and sought to arrest five members on the 4th January 1642. They fled before his arrival Charles abjectly declared "all my birds have flown", and was forced to retire, empty-handed. No English sovereign had ever entered the House of Commons, and his unprecedented invasion of the chamber to arrest its members was considered a grave breach of parliamentary privilege. Charles fled London and both sides began to arm for war.

Events in Chester

Events in Chester which can be linked to the Civil War date back to 1637. They did not cause the war but simply provide a local perspective on divisions and disputes which were present in similar forms elsewhere. These include issues over religion, which was even the subject of "fake news" and often complicated by disputes over trade and governance.

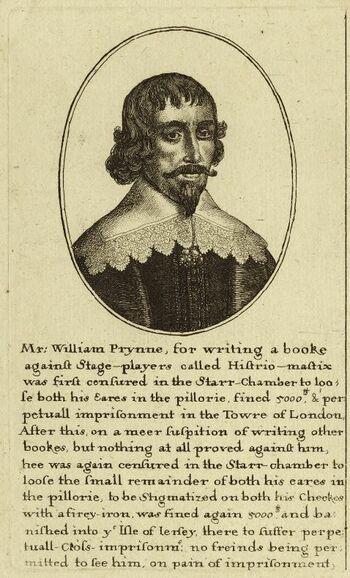

Prynne

William Prynne (1600 – 24 October 1669) was an English lawyer, author, polemicist, and political figure. He was a prominent Puritan opponent of the church policy of the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud. On 31 May 1630 Prynne obtained a licence to print his book against stage-plays, and about November 1632 it was published. "Histriomastix" or, as it was otherwise known, "A whip for stage-players" - a volume of over a thousand pages, showing that plays were unlawful, incentives to immorality, and condemned by the scriptures, Church Fathers, modern Christian writers, and pagan philosophers. By chance, the queen and her ladies, in January 1633, took part in the performance of Walter Montagu's "The Shepherd's Paradise": this was an innovation at court. A passage reflecting on the character of female actors in general was construed as an aspersion on the queen; passages which attacked the spectators of plays and magistrates who failed to suppress them, pointed by references to Nero and other tyrants, were taken as attacks Charles I. William Noy as attorney-general instituted proceedings against Prynne in the Star-chamber. After a year's imprisonment in the Tower of London, he was sentenced (17 February 1634) to be imprisoned during life, to be fined £5,000, to be expelled from Lincoln's Inn, to be deprived of his degree by the University of Oxford, and to lose parts of both his ears in the pillory. Prynne was pilloried on 7 May and 10 May. Some of the judges outbid each other in suggesting refinements or additions to Prynne’s punishment. Lord Dorset urged greater violence against Prynne’s body, to have him "branded in the forehead, slit in the nose, and his ears cropped too". King Charles, it seems, was content with Prynne’s treatment, though Henrietta Maria had made some intercessions for mercy and pardon. William Noy, the Attorney General, was said to have laughed so hard while Prynne was suffering on the pillory that he was:

- "..struck with an issue of blood in his privy part, which by all art of man could never be stopped unto the day of his death, which was not long after"

Prynne could not later resist telling this story, which could be read as a providential judgement. Prynne was subjected to further punishment and eventually, in 1637, it was decided he would be moved to an isolated prison at Caernarvon Castle. Hemingway writes, in his "Panorama":

- In the year 1636 the celebrated William Prynne, who, by his hostility to the hierarchy and the measures of government, had incurred the hatred of the court, and become popular through the country by the severe persesecution of the star chamber, was conveyed through Chester, on his way to Carnarvon, to be imprisoned in the castle there. On his approach to the city, he was met by numbers, who had imbibed like sentiments with himself, and who testified towards him the most unmeasured sympathy and approbation. This conduct was narrowly watched, and eagerly represented by the emissaries of the court, and some were fined £500 some £300 and others £250.

Calvin Bruen was one of those arrested and only released after making a public confession both in the Cathedral (17th December 1637) and in the Commonhall in Chester, of how he had behaved "audaciously and wickedly". The sketches of Prynne were destroyed by the authorities in Chester. In order to destroy any trace of the sketches the now-empty frame were ceremoniously burned at the High Cross on 12th December 1637 - before (it is said) a large crowd shouting "burn them! burn them!". As Prynne himself put it:

- "these High Commissioners not satisfied with the defacing of the pictures, would needs proceed to burn them for heretics; and since they could not burn Mr. Prynne in person as they desired, being then on the sea sailing to Jersey, they would do it at least by effigy; and to show the extravagance of their unlimited malice, not only the pictures but the very frames wherein they stood (poor innocents) must to the fire".

Bishop Bridgeman may have had a personal reason to dislike the Bruens. His daughter Elizabeth had died, aged about six months, on Ascension Eve 1613: the very day that John Bruen was busy smashing crosses in and around Tarvin.

Prynne was released from captivity in 1641 and continued his attacks on the Anglican church. He noted that Bishop Bridgeman had installed a stone "altar" in the Lady Chapel and mentioned it as:

- "one in the Cathedral at Chester used in times of popery, which he caused to be digged up out of the ground where it was formerly buried".

The "altar" can actually be identified from a confrontation which Bridgeman had with John Ley, the pastor of Great Budworth, Cheshire, another lecturer at St Peter's. Ley's letter (Against the erection of an Altar) Written June 29th 1635, to the Reverend father Iohn L. Bishop of Chester ("Iohn L" appears to be John Lloyd) expressed his opposition to what was variously described as an "altar" or "a funerary monument to St Werburgh". After the Reformation St Werburgh's shrine served as the burial place for Bishop Downham, but in 1635 the base and part of the upper section were adapted to make a throne for the Bishop of Chester, presubably John Bridgeman.

Propaganda

The principal source for Bruen’s life and the foremost reason why he has been accorded such significance is the contemporary biography by William Hinde (1568/9–1629), curate in the parish of Bunbury, and Bruen’s brother-in-law. This was published posthumously in 1641 by Hinde’s son, Samuel, himself a clergyman. Whether the text had been mislaid, simply overlooked, initially under-valued, or held back during the intervening twelve years is not clear. It is easy to assume that the publication was intended to stir up religous arguments. This was not the only inflamatory publication: according to some published accounts, as part of the Irish rising of 1641, a conspiracy was attempted by Lord Cholmondeley and some of his fellow Cheshire Papists. It had supposedly been ordered by Parliament that all Papists should be disarmed, but those in Cheshire refused to obey so the Trained Bands (the local Militia) were employed to search for the culprits with instructions to destroy the houses of any who declined to yield. The events have been reported as follows:

- On 20 November, the Papists, having obtained news of this intention, gathered themselves together at the Cholmondeley mansion, and in the night sallied out and commenced to attempt to batter down the walls of the city. Unsurprisingly, this made "a very great noise" and soon drew the attention of the City Watch, who were "very much amazed" but, being mostly elderly men, retreated to the city gate where they loudly cried out "treason, treason, against the city!". By the time the Trained Bands were alerted, most of the party had escaped, but two stragglers who were captured said that the rest were running to Lord Cholmondeley's house. They were pursued and taken at the gate as the guard on duty at it had thought the fugitives belonged to the Trained Band and would not allow them to pass through to safety. The fugitives were arrested and a strong guard left at the house so that none of the Papists there might leave. After the prisoners had been "lay'd fast" the Trained Bands returned to the house and demanded admittance which was refused. Muskets were discharged at the house and when part of it had been battered down, Lord Cholmondeley escaped by a postern door which opened on to the fields. Most of the Trained Band then went into the house and searched it, and coming into a private wood-house there, to their horror came face to face with 50 Papists with charged muskets. These were discharged and 25 of them were killed. The Papists retreated through a back door out of the wood-house but were met by the remainder of the Trained Band and a battle ensued. At length the Papists were routed and "trusted to the swiftness of their feet", but 19 of them, including their leader, Henry Starkey, were nontheless shot in the back. These unfortunates were later "buried in the highway together". (see: Tracts relating to the civil war in Cheshire for the full text)

The above account is based on a publication entitled: "True Relation of a Bloody Conspiracy by the Papists in Cheshire. Intended for the Destruction of the Whole Country, London, 1641". There are several things which are at once suspicious about it: despite the considerable number of fatal casualties (at least 44) there seems to be no record of it in the Chester Corporation or Mayor's papers, or indeed in any other contemporaneous account. The very idea that a relatively small number of people could pull down the City Walls without being prevented seems absurd. Cholmondeley, who was in the upper ranks of the Royalist command structure, seems to have suffered no negative consequences. There is also the rather remarkable potency of the catholic weapons - 50 "papists" in a woodshed discharge a volley and kill 25 of the Trained Band (even at close quarters this is remarkable shooting, and makes no mention of how many of the Trained Band were "merely" wounded) and then, with empty weapons, all 50 "Papists" manage to scatter through a back door.

The "True Relation" was one of many fantastical tracts which appeared at the time: pamphlets describing various plots, conspiracies and planned attacks were quite numerous. Many of these were complete fiction and in mid-November 1641 the Commons committee charged with the supervision of the press was required to find "some means to restrain this licentious printing". In January 1642, John Greesmith, who was also responsible for publishing many of these pamphlets admitted to the Commons that he had actually arranged for "sundry pamphlets" with titles like "Good News from Ireland" to be written by two "dropout" Cambridge students for 2s 6d a copy. Such was the scale of Greensmith's creation of "fake news" that it became, in January 1642, the subject of "The Poets Knavery Discouered" a pamphlet (by John Bond - another "hack writer") which listed the printed falsehoods of Greensmith:

- "The Poets Knavery Discovered, in all their lying Pamphlets wittily and very ingeniously composed; laying open Names of every lying Libel that was Printed last Year, and the Authors who made them; being above three hundred Lies. Shewing how impudently the Poets have not only presumed to make extreme and incredible Lies but dare also feign false Orders and Proceedings from the Parliament with many fictitious Speeches Well worth the reading and knowing of every one that they may learn how to distinguish betwixt the Lies and real Books Written, by JB"

While the supposed skirmish at the Cholmondeley mansion in what is now Grosvenor Park never in fact took place it is frequently mentioned in guidebooks to Chester.

Brereton

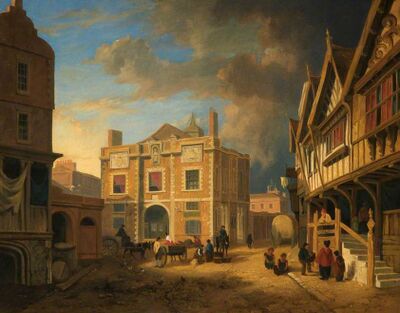

In the summer of 1642 Commissioners of Array for the King and Deputy Lieutenants for Parliament attempted to raise the Trained Bands and to seize the magazine in every county. During the confusion caused by the troops waiting to be shipped from Chester to Ireland to suppress the rebellion there, Sir William Brereton, the Parliamentary representative in Cheshire, turned to what was virtually recruiting. He found himself opposed by Sir Thomas Aston and all the resident Cheshire nobility and he failed in his attempt to secure Chester for Parliament (8th August, 1642). According to Frank Simpson, mayor Cowper ordered the constables to arrest the leaders of this "treasonable" gathering, but they failed to do so. At this point Cowper stepped-in and seized one of the leaders by the collar, delivering him to the civil officers. He also wrested a broadsword from another of the party, which which he cut the drum to pieces. Thomas Hughes in the Journal of the Architectural, Archaeological, and Historic Society, Volume 2 is recorded as reporting a follows:

- Mr T HUGHES volunteered some remarks on the Cowper Family of Overleigh and especially on those members of it connected with the siege of Chester He exhibited an old portrait in oil colour of Alderman Thomas Cowper Mayor of Chester in 1641 which had been recently presented by Mr J Edisbury of Bersham near Wrexham to the Water Tower Museum Chester. Mr Cowper was Mayor of this city the very year in which a drum was beaten for the Parliament at the instigation of Sir William Brereton and Mr Hughes quoted the following passage from Hemingway's History of Chester to show how boldly and bravely his Worship put down the first symptom of rebellion: Information of this treason having been given to the Mayor Mr Thomas Cowper this intrepid magistrate immediately directed some constables to apprehend the leaders of the tumult but the latter forcibly resisted and compelled the constables to retire upon which the Mayor stepped forward in person to expostulate with them on their conduct and upon being disrespectfully treated he boldly advanced up to one of the Parliamentarians and seizing him by the collar delivered him to the civil officers at the same time wresting a broad sword from another of the party with which he instantly cut the drum to pieces securing the drummer and several others This firm and manly demeanour on the part of the Mayor effectually put an end to the tumult and finally repressed it During this affray the common bell was rung the citizens lent their cheerful aid to the chief magistrate and when they had seen him in a state of personal security the city was restored to peace Sir William Brereton a gentleman of competent fortune in the county and knight for the shire and who was a strong partizan for the Parliament was brought before the magistrates at the Pentice to answer for the part he had taken in the above disturbance though he owed his rescue from the popular fury to the personal interference of the Mayor he was however discharged.

As for why the "constables" would not arrest Brereton it could be that they believed (perhaps wrongly) that Brereton, as an MP, enjoyed the benefit of freedom from arrest on civil matters. Brereton's unsuccessful advemture is depicted in the sculptural works in the Town Hall: he was put on trial before Maoyor Cowper then given a safe escort out of the City.

On 22 August 1642, Charles took a decisive step by raising the royal standard in Nottingham, effectively declaring war on Parliament. The Midlands were generally Parliamentarian in sympathy, and few people rallied to the King there, so having again secured the arms and equipment of the local trained bands, Charles moved to Chester and subsequently to Shrewsbury, where large numbers of recruits from Wales and the Welsh border were expected to join him. Having learned of the King's actions in Nottingham, Parliament dispatched its own army northward under the Earl of Essex, to confront the King. On 23 September, in the first clash between the main Royalist and Parliamentarian armies, Royalist cavalry under Prince Rupert of the Rhine routed the cavalry of Essex's vanguard at the Battle of Powick Bridge. Nevertheless, lacking infantry, the Royalists abandoned Worcester.

Bunbury - a "what if"

The prevailing mood in Chester in summer 1642 was a wish for accommodation between Charles I and parliament, reflected in the city's neutralist petition in August and in its reaction to the parliamentary commission of lieutenancy and the royal commission of array. In July Richard Grosvenor played a leading role in organizing, and probably also drafting, the Cheshire remonstrance, a petition containing over 8000 signatures, which called on the King and Parliament to settle their differences and avoid Civil War. The Assembly stood fast against both an attempt by James Stanley, Lord Strange, to secure the county magazine in the castle for the royalists, and Alderman William Edwards's and Sir William Brereton's effort to take control of the city's trained bands for parliament. Nevertheless, Bishop of Chester John Bridgeman, his son Orlando Bridgeman (vice-chamberlain of Chester), other lawyers, and prominent figures were apparently trying to encourage royalist sympathies among leading citizens. On 6 September Mayor Thomas Cowper secured a majority vote in the Assembly for an immediate assessment of 100 marks to fortify the city. The decisive event, however, was the arrival of the king himself in Chester on 23 September. In an upsurge of loyalty he was greeted with popular enthusiasm, pageantry, bellringing, and a loyal address. The king's supporters seized their opportunity. The houses of known opponents, such as Brereton and Aldermen Edwards and Aldersey, were searched for arms; county gentlemen favourable to parliament were rounded up; and parliamentary supporters in the corporation left. When the king departed five days later, with a gift of money from the corporation, the parliamentarian presence in the city had all but gone, and the royalist hold on Chester had finally been consolidated.

There was one forlorn hope that destructive conflict in Cheshire could be avoided. After a summer of skirmishes in Cheshire, the sometime pirate Henry Mainwaring and Mr. Marbury of Marbury Hall for Parliament and [ Lord Kilmorey] and Sir Orlando Bridgeman, son of the Bishop of Chester, for the Royalists agreed to meet on December 23rd 1642 at the township of Bunbury on the River Gowy (which is there little more than a brook). There, they tried to broker a peace.

The details of the whole affair are lost, but the very choice of Bunbury leads to some interesting speculation. Bunbury had been the home of the same William Hinde a leader of the nonconformists in Cheshire who wrote his book on Bruen and was probably Bruen's brother in law. They agreed that all fighting in Cheshire would end. All prisoners would be released, property taken during the conflict returned to its owners and any losses compensated by a levy on both sides. Fortifications were to be removed at Chester, Nantwich, Stockport, Knutsford and Northwich and their combined forces would escort any external forces out of the county. Both parties agreed that there were to be no further troop movements through Cheshire, and that they would not to raise any more troops locally. Everything depending on the agreement of their national commanders, whom they would urge to settle their differences peacefully.

Unfortunately the Bunbury Agreement was never to be ratified. Had it been the course of the Civil War might well have shifted towards a national search for a peaceful settlement, religious liberty and balanced government. The men of Chester and Cheshire had for once remembered their common heritage and settled their differences, but it came to nothing. The consequences would be tragic: one of the sons of the occupant of Brereton Hall is later said to have scratched on a window:

- "On yonder hill my uncle stands, but he will not come near, for he is a Roundhead, and I am a Cavalier."

Historians now appear to agree that the Civil War had several causes. There were religious tensions between Puritans, High Anglicans and Catholics, tensions between the Scots and the English, and troubles in Ireland. There were tensions between whether the form of government should be based on a Divine Right of Kings or an elected Parliament (with a limited electorate), especially as regards how taxes should be levied. The advent of printing allowed for the spread of political and religious literature which was often the subject of savage suppression. A voting block of bishops in the House of Lords further complicated matters.

Civil War