The Rows

One of Chester’s most distinguishing features are its Rows. These are galleried walkways that run the along the four principal streets which meet at the High Cross. The origin of the Rows was once a major mystery, with several theories being put forward for their existence. Many of these theories are now considered to be the speculations of antiquarians and while some progress has been made to understanding what the Rows are (and what they are not) several puzzles remain as to their origins. As a general statement it is still fair to say that the origins of the Rows remain unknown.

The four streets which include Rows, each of which leads to one of the principal City Gates of Chester, are:

Each of these streets is of Roman origin and, as described below, this has led some to speculate that the Rows are also of Roman origins. Their story is however far more complex and, as noted above, there are still many unanswered questions about their construction. While many of the buildings on the Rows are "listed" they do not have "World Heritage" status.

It seems that almost every building in the Rows has its own story to tell. The "Rows of Chester" book is an excellent reference to them and the detailed archaeological work done in the 1980's-90's. Other bits of their history are recorded on this site. If you are aware of more, please consider informing the site via its Facebook page.

The Rows on these streets are known as "Bridge Street Row" etc., and one curiosity of Chester is that the house numbers on the streets and the Row above may differ significantly. For example, 49 Bridge Street forms the ground floor of 57 Bridge Street Row. Indeed, the Row houses and the Street houses are often under different ownership. While the Rows themselves are a public right of way they are in private ownership and the owners are responsible for their upkeep. Also, local bye-laws do not permit smoking on the Rows. Some parts of the rows have secondary names which derive from the traders who carried on their business there (Shoemakers’ Row, Ironmongers’ Row, etc). Today they mostly house a variety of small shops, bars and restaurants, although there are still some private houses on the Rows. In some places the Rows have been "enclosed", that is the Row has been blocked-off at both sides and the space has been incorporated into a building. Often, as in Lower Bridge Street, the internal layout of these buildings reflect the fact that the Row once passed through them - a particular example is the Old Kings Head, another is The Falcon. Mostly, the rows are open on the street side, but there is one exception, the so-called "Dark Row" where there are shops between the Row and the street frontage.

The advantages of a pathway at first-floor level were too obvious to be overlooked, as the condition of the street below, badly paved, encumbered with horses and wagons, littered with refuse, and at times with a rough channel in the center as the only drain, made things decidedly unpleasant for the medieval pedestrian. On the first-floor level the merchant would have an opportunity of attracting customers, who would be able to make their purchases in comparative peace, while the natural advantages of the street-level frontages induced others to open their "shops" there.

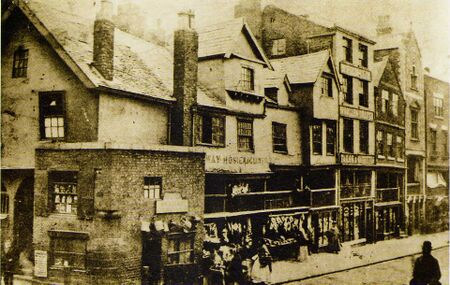

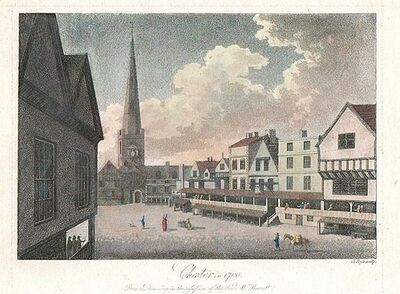

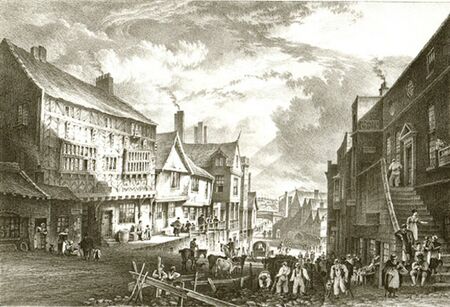

It is often said that The Rows are "fake" and that much of them dates only from around 1900, but to say so is to be both superficial and inaccurate. Chester has been very well documented by artists over the years and these often very detailed depictions of The Rows, including those of Louise Rayner and the less well-known Batenham show just how much of the general form has survived from the early 19thC. However, the Rows seen today do differ from their Medieval counterparts, as while the form has been retained during rebuilding in many places there have been significant improvements to the headroom and lighting.

The sequence at Chester was often that:

- during medieval times, buildings in Chester were constructed with a stone "undercroft" and the row-walk above, a medieval timber-framed building was constructed above that;

- by the end of the 18thC, most of the timber-framed medieval buildings had been re-fronted in brick, cutting away the jettied storeys to give a flat facade, but sometimes leaving much of the original timber framing behind; often, but not always, the row level was preserved;

- in the "Vernacular Revival" (after about 1860) some of the brick frontages were embellished with their "mock Tudor" appearance of the current day

So what we often perceive as "fake medieval" sometimes has a "mock-Tudor" cosmetic mask over the Georgian face of a real Tudor or Medieval building. However, in many cases very little above the level of the undercrofts has not at some point been replaced.

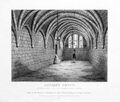

The best surviving undercrofts are:

- 12 Bridge Street (Cowper House);

- 28 Eastgate Street (Brown's Crypt),

- 11 Watergate Street (Watergate's Wine Bar);

- 21 Watergate Street (Leche House);

- 37 Watergate Street (St Ursula's);

Leche House (1603-1625)

Bishop Lloyd's House (1890/1615)

The Falcon (1982/c1180)

Is there anything similar elsewhere?

The Rows are almost unique. There is something similar in Steigstrasse in the Obertor at Meersburg in Germany but not on so large a scale, and the earliest surviving building of the "rows" type in Meersburg is believed to date from 1620, much later than The Rows in Chester. Parallels have also been drawn with some arcades in Istanbul, but these seem much too modern.

Trajan's Market in Rome (probably built in 100-110 AD by Apollodorus of Damascus) has also been cited as a forerunner of the rows, but again there is unlikely to be any causal connection. Other early English towns have have stretches of covered pavement with the buildings above supported on pillars, but all these covered ways are at street level. William Smith (1588 - he of the Smith Map) writing in The particular description of England (see page 44 for Chester) says:

- The Buildings of the City are very ancient; and the Houses builded in such sort, that a man may go, dry, from one place of the City to another, and never come in the Street; but go as it were in Galleries, which they call, the Roes, which have shops on both sides and underneath, with divers fair staires to go up or down into the street. Which manner of building I have not heard of in any place of Christendome. Some will say, that the like is in Padua in Italy, but that is not so. For the houses in Padua, are builded as the Suburbs of this City be, that is, on the ground, upon Posts, that a man may go dry underneath them; like as they are at Billingsgate in London, but nothing like to the Roes..

One thing that is similar but seldom mentioned are "bastides". Bastides are fortified new towns built in medieval Languedoc, Gascony, Aquitaine, and in England and Wales. Flint is the closest example to Chester. Most bastides were developed with a grid layout of intersecting streets, with wide thoroughfares that divide the town plan into "insulae", or blocks, through which narrow lanes often run. The continental bastides included a central market square surrounded by arcades (couverts) through which the axes of thoroughfares passed, often with a covered weighing and measuring area in the market square. Chester does not have all of the features of a bastide and notably the arcades of bastides are at street level.

What is the most efficient way to walk round them?

The Rows provide for a dense commercial environment, and convenient shelter from inclement weather. Because The Rows effectively double the number of shops, it may mean that the visitor has to walk the length of a street three times (once in the street and once in each row) to see everything. Matters are further complicated by the presence of a few other retail areas within the City Walls off The Rows: for example Pepper Street, St Werburgh Street and at least three shopping arcades (the Grosvenor Shopping Center, Handel Court/Rufus Square and (until recently) The Forum - the last once leading to the traditional indoor market). There are also some shopping streets outside of the walls: notably Frodsham Street, Brook Street (Ethnic restaurants and food stores, second-hand goods and clothes, comics, records and computers) and Foregate Street. If you are a "systematic shopper" and want a route round Chester to see all the shops and not retrace your steps, you are in for a difficult time. Often, the more interesting shops are tucked away into some obscure corner.

The Rows are much commented upon by visitors to Chester, who often fail to see the attraction of resting on the Rows and watching the world go by. Writing in 1840, General Sir Charles Napier (then stationed at Chester Castle as a precaution against Chartist riots) said of the Rows:

- All the rogues, and fools and drunkards in the country seem collected, and the Row balconies are filled all day with idlers and well-dressed girls, young and old, looking into the streets from daybreak till dark. Such idleness I never witnessed as at Chester. My life has been long, it has but twelve years to run, and yet I never, in any country, witnessed such stupid idleness as in Chester. Those who go to the course have some fun, but those who hang over the Row balconies all day like old clothes, see nothing, hear nothing, do nothing.

Rather more modern Rufus Court close to the Northgate, tries to emulate the atmosphere of the Rows.

Why The Rows?

The early buildings along the Rows had some common features which are retained in a few cases. They were constructed on plots with a narrow street frontage which ran back for some distance. The lowest floors are often still the "undercrofts" which were almost invariably built at the front of plots and at right angles to the street, and were only partially below ground level. These were common in Medieval English towns and provided secure storage for valuable goods such as wine. These varied in size from 3.7 m. to 9 m. in width, and from 10 m. to 41 m. in length, and do not seem to have been the product of a single plan. Above them, at Row level, were groups of small shops usually no more than 2 m. wide and 3 m. deep. A single merchant house might contain anything up to five such tiny "lock-ups". Behind the shops, at Row level and above, lay domestic accommodation reached by passages leading from doors opening on to the walkway. Buildings took two main forms. In the simpler and much more common type the hall was placed at right angles to the Row, while in the grander houses, usually at corner sites, it ran parallel to the walkway across several undercrofts. The presence of the Row affected the layout of the houses, precluding the courtyard plan found in other towns. The Row's overriding importance in the planning is evident from the fact that the main entrance at the cross-passage of such houses was approached from the street only indirectly and inconveniently by steps at either end of the frontage.

Despite the unique presence of the Rows the Chester buildings do share some features with Medieval town houses elsewhere. Tackley's Inn at Oxford, believed to be built around 1320, has an undercroft with its own street entrance, small shops above this and a hall behind the shops. 58 French Street in Southampton follows a medieval right-angle, narrow plan design, in that the hall, fronted by a shop, stretches away from the street to conserve frontage. In the Southampton instance, a gallery in the hall grants access to rooms over the shops and there is an undercroft. There are many similarities with Leche House in Chester. However, one thing which distinguishes Chester is that almost every Medieval building in the main streets seems to have had an undercroft and a Row walkway.

Antiquarian Explanations

The first antiquarian mention of the Rows appears to have been made by John Leland in his "Itineraries" of the 1540's. Leland only makes a passing reference to how in a street at Bridgnorth "men may passe drye by them yf it raine". He then suggests that there is something similar at Chester, so the reference is not only brief but indirect. The street at Bridgnorth to which Leland refers has never been identified.

Much else has been written over the years on the origin of The Rows. Some of this was barely more than guesswork, but found its way into guidebooks, which frequently added their own theories about the origins of the Rows. More realistic archaeology was not done until the 20th century but even this has not solved all of the mysteries associated with the Rows.

Here are some previous explanations, many of them are now believed to be wrong but come from writers whose other statements are often relied upon in following the history of Chester:

Ormerod believed that the early inhabitants of Chester lived under the ground. Although the first edition of his major work on Chester contains some errors he is generally a reliable source. He writes (in 1819):

- " .. yet may I not let pass what I find to be conjectured of the beginning of this manner of building with rows. It is not only apparent by the writing of the most antient concerning the city's beginning, but also by the very workmanship of those parts of it, which are of greatest antiquity, that at the first they partly won them habitations out of the very hard rock, and partly by their own industrious building artificial!}' with stone, they made their chiefest abodes rather under than even with the upper face of the earth .. Now we may well think, that as they grew in strength and force able to defend themselves, and in time, no doubt, enlarged themselves, both for more safe, and more pleasant beings ; then set they new additions upon the former foundations, which might be more comfortable, and of convenienter use for strength, for health, and for delight ; and because their conflicts with enemies continued a long time, it was needful for them to leave a space before the doors of those their upper buildings, upon which they might stand in safety from the violence of their enemies horses, and withall defend their houses from spoil, and stand with advantage to encounter their enemies when they made incursions .. That this is no naked assertion of my own, I confirm it by that which Mr. Rogers, out of his reading, hath collected in these words :this city, which in time of wars in this kingdom was a place of great refuge and service far before Wales was subdued, Chester, was of no small force to keep them under. And, in those times, many of the inhabitants of this city did build rows and walks before their houses, that thereby, when the enemy entered, they might avoid the danger of the horsemen, and might annoy their enemies as they passed through the streets."

Others hint that the origins of the Rows are far less clear and introduce the idea that the Rows date from Roman Chester:

- "The greatest peculiarity of Chester—greater even than its Roman walls—lies in its sunken streets and the famous "Rows." These are unique in England, and indeed in Europe. Likenesses to them are seen in Berne, Utrecht and Thun, but nothing just the same, nothing so evidently systematic and prearranged, is to be found anywhere. The principal streets, especially the four great Roman ones that quartered the camp, are sunk and cut into the rock, while the Rows are on the natural level of the ground. The reason for this has been a standing problem to antiquaries. Some have supposed that the excavation of the streets dates from Roman times, and was only due to the necessity of making work for the soldiers during long periods of inaction. The effect is most singular. Hardly any description brings it satisfactorily before the eye of one who has not seen it. The best which I have met with, and a much better one than I should be able to give from my own experience, is that of a German traveller, J.G. Kohl: "Let the reader imagine the front wall of the first floor of each house to have been taken away, leaving that part of the house completely open toward the street, the upper part being supported by pillars or beams. Let him then imagine the side walls also to have been pierced through, to allow a continuous passage along the first floors of all the houses.... It must not be imagined that these Rows form a very regular or uniform gallery. On the contrary, it varies according to the size or circumstances of each house through which it passes. Sometimes, when passing through a small house, the ceiling is so low that one finds it necessary to doff the hat, while in others one passes through a space as lofty as a saloon. In one house the Row lies lower than in the preceding, and one has in consequence to go down a step or two; and perhaps a house or two farther one or two steps have to be mounted again. In one house a handsome, new-fashioned iron railing fronts the street; in another, only a mean wooden paling. In some stately houses the supporting columns are strong, and adorned with handsome antique ornaments; in others, the wooden piles appear time-worn, and one hurries past them, apprehensive that the whole concern must topple down before long. The ground floors over which the Rows pass are inhabited by a humble class of tradesmen, but it is at the back of the Rows themselves that the principal shops are to be found.... The Rows are in reality on a level with the surface of the ground, and the carriages rolling along below are passing through a kind of artificial ravine. The back wall of the ground floor is everywhere formed by the solid rock, and the courtyards of the houses, their kitchens and back buildings, lie generally ten or twelve feet higher than the street." - LIPPINCOTT'S MAGAZINE - Nov 1877, Lady Blanche Murphy.

Artist Louise Rayner wrote of the many theories on the origin of the Rows:

- To trace the original cause of these rows, with any degree of certainty, is no easy task, concerning which a variety of conjectures have been formed. Some have attributed their origin to the period when Chester was liable to the frequent assaults of the Welsh, which induced the inhabitants to build their houses in this form, so that when the enemy should at any time have forced an entrance, they might avoid the danger of the horsemen, and annoy their assailants as they passed through the streets.

Rayner is simply quoting earlier writers, including Ormerod but expresses some scepticism. Much the same view is stated by Daniel Lysons writing (in his Magna Britannia) in 1810:

- The city of Chester still surrounded by its ancient walls is divided into four principal streets called Eastgate street, Northgate street, Bridge street and Watergate street. The carriage road in these streets is on a level with the underground warehouses over these are open galleries called row for the accommodation of foot passengers which occupy the space between the front of the tradesmen's shops and the street, the upper rooms of the houses project over the rows so as to be even with the warehouses beneath. The general appearance of these rows is as if the first stories in front of all the houses had been laid open and made to communicate with each other pillars only being left for the support of the superstructure the foot passengers appear from the street as if they were walking along within the houses up one pair of stairs At the intersections of the streets there are flights of steps leading to the opposite rows. Some of the rows are so wide that the proprietors of the houses place stalls between the footway and the street which they let out advantageously to other tradesmen particularly during the fairs. Mr Pennant thinks that he discerns in these rows the form of the ancient vestibules attached to the houses of the Romans who once possessed this city many vestiges of their edifices have certainly been discovered at Chester as we have already noticed: but there seems to be little resemblance between the Chester rows and the vestibules of the Romans whose houses were constructed only of one story. Some have attributed the origin of the rows to the period when Chester was liable to frequent attacks from the Welsh which induced the inhabitants to build their houses in this form that when the enemy could at any time have forced an entrance they might avoid the danger of the horsemen and annoy their assailants as they passed through the streets.

From Lysons and Ormerod it seems that canon Robert Rogers (died 1595) was possibly the source of the "Welsh" theory.

Samuel Lewis, in 1848 had set out similar theories, both of Roman survival and Welsh attacks:

- The streets of Chester, being cut out of the rock, are several feet below the general surface, a circumstance that has led to a singular construction of the houses. Level with the streets are low shops, or warehouses, over which is an open balustraded gallery, with steps at convenient distances into the streets; and along the galleries, or, as they are called by the inhabitants, "rows," are houses with shops: the upper stories are erected over the row, which, consequently, appears to be formed through the first floor of each house; and at the intersection of the streets are additional flights of steps. The rows in Bridge and Eastgate streets, running through the principal part of the city, are much frequented as promenades. Pennant considered these curious galleries to be remnants of the vestibules of Roman houses; but other writers are of opinion that they were originally constructed for defence, especially against the sudden inroads of the Welsh.

Early architectural drawings of Chester are rare. There is a purported drawing of "Chester in 1700. From a drawing in the possession of the Revd. M. Prescott". This is said to be an aquatint engraving by F. Ross (c1800), but little is known about the history of the work. The illustration shows St Peters in the distance, still with its original spire. This spire was removed and rebuilt in the 16th century, taken down in the 17th century, then rebuilt and finally removed "having been much injured by lightning" about 1780. While the illustration shows a part of the Pentice fronting onto St Peter the details of this are not clear which leads to suspicions that the rest of the illustration may be less than wholly accurate and possibly drawn from written descriptions. One notable feature of the Rows as shown in the illustration by Ross is that they appear as an addition to the front of the buildings in a Bridge Street which is depicted as being much wider than it actually is.

Hanshall (1823) favours the "Welsh" theory:

- The origin of this irregular style architecture goes back no doubt to the times when the neighboring Welsh made inroads on the city when the Inhabitants defended themselves and beat their assailants from these galleries

William Webb, writing in about 1700 proposed that the inhabitants of Chester originally lived in the undercrofts and again repeats the theory that the Rows were a defensive measure.

George Borrow, author of the travel book "Wild Wales" stayed in Chester in 1854 (probably at the Pied Bull) and wrote the following (again somewhat anti-Welsh!) description of the Rows which favoured the "defensive" theory.

- All the best shops in Chester are to be found in the rows. These rows, to which you ascend by stairs up narrow passages, were originally built for the security of the wares of the principal merchants against the Welsh. Should the mountaineers break into the town, as they frequently did, they might rifle some of the common shops, where their booty would be slight, but those which contained the more costly articles would be beyond their reach; for at the first alarm the doors of the passages, up which the stairs led, would be closed, and all access to the upper streets cut off, from the open arches of which missiles of all kinds, kept ready for such occasions, could be discharged upon the intruders, who would be soon glad to beat a retreat.

Many descriptions of Chester note that the ground behind Row properties is the same level as the first floor walkway and is thus generally c.9ft (3.3m) higher than at the street frontage. As can be seen from the various explanations quoted, a theory was once put forwards that the Romans dug the streets out as ditches in the bedrock, either to provide work for the Legionaries or so that they would have less of a hill to climb from the river. The Romans are not known to have done this on any other site.

Others have claimed that the difference in level came about because of the differential clearance of the ruins of Roman buildings. "Ruins" were removed along the frontages of the main streets because such areas were the most sought after as building plots in the medieval town where the majority of the inhabitants made their living through commerce. The creation of a small hill by the accumulation of the remains of earlier buildings and various rubbish is quite a common archaeological feature - it is known as a "Tell". Other guidebooks inform us that when Chester's medieval merchants came to construct cellars or "undercrofts" beneath their town houses, they were forced to build on top of the bedrock, which is almost at street level, hence the "cellars" were mostly above ground level. However, the debris slopes behind their houses, meant that while the front of these properties could be as much as 2m above street level, the rear corresponded with ground level.

Some theories hold that the Welsh connection is in fact the reverse of what Lewis, Rayner and Borrow suggest. Edward I used Chester as his base for military campaigns against North Wales in 1277 and 1282, and hundreds of masons, carpenters and labourers employed to build the "Welsh" castles had their winter billet in Chester. Some early historians believed that the city was at the height of its prosperity and wealthy merchants could embark on a building boom with some of the country's most highly skilled craftsmen on hand.

In another theory the origin of the Rows involved a major fire. In the Chester Chronicle, the monks of St Werburgh's Abbey record that on the 15th May 1278 "almost the whole of Chester within the walls of the City was burned down". It has been argued that this could have provided a basis for a planned re-construction of the City involving the construction of The Rows. However, despite the supposed documentary evidence for the fire there is no evidence from archaeology of the extensive burnt debris horizon that such a major fire should have left. However a fire in Flint (during the Welsh War of 1294-95, being deliberately set on fire by the constable of the castle when it was thought that the Welsh would take the town) led to remarkably small claims for damages as much survived in cellars. It is therefore possible that The Rows were constructed to provide secure and relatively fireproof storage below the the merchants houses which would have been mainly of timber construction above.

One pre-requisite for the development of The Rows would appear to have been a more or less continuous occupation of the frontages onto the main streets. Examination of these frontages as shown on early Ordinance Survey maps shows that the widths are consistently multiples of eleven yards (just over 10m), which is half of the unit known as a "chain" (i.e. two rods, perches or poles) - the "chain" also survives as the distance between the stumps on a cricket pitch. That could mean that the surveyors of the early OS map worked to the nearest half-chain (these units were still in use until the 1960's), or it could mean that the plots were laid out in a regular fashion long before The Rows were constructed.

By about 1350 the Row system seems to have been largely in place. The frontages along the four main streets were lined with galleries, while "stallboards" on the street side of the walkway maximised the commercial potential of each building by allowing both a street level stall to be set up beneath it and goods to be laid out on the upper surface of the stallboard at row level. These stallboards can be seen in many places and form a sloping roof of the building below allowing for the headroom needed to enter.

A further issue about the Rows is how they managed to survive centuries of rebuilding the redevelopment. An early theory was that the plagues of the middle ages brought a temporary reduction in prosperity and a hiatus in new building. Others have argued that the silting of the Dee and it's depressive effect on trade as one reason why so much of the Rows have survived.

A List Of Explanations

From the writers quoted above the following possible "antiquarian" explanations for the development of the Rows can be listed:

- The Romans cut the principal streets into the rock - possibly to lessen the slope on Bridge Street, possibly just to create work for the troops;

- Rather than the roads being sunken, the land to the sides of the main streets has been built-up by the ruins of substantial buildings which had collapsed;

- The "sunken" streets were a defense against the Welsh (on horseback): presumably, if the walls were breached, then Cestrians could pelt them with stones etc from the Row walkway;

- The Rows were a planned development to provide shelter from the weather and/or separate commercial activity from the mess and traffic in the streets;

- The Rows enabled twice as many shops to be accomodated on the valuable street frontage;

It was only when the architecture of individual buildings was considered that the origins of the Rows became clearer, although many of the earlier "modern" interpretations are now known to be wrong. This did not prevent them being presented in many guidebooks printed up to the late 1950's.

In 1887 John Hewitt studied the few surviving medieval buildings and concluded that the front walls rose straight up from the streets. Hewitt considered that the principal floor (the first floor) was reached by a set of external steps. Subsequently, the upper floors were extended outwards into the main streets covering the steps and the undercrofts were also extended outwards. Then, according to Hewitt, the rows were created by demolishing the front walls facing the street and sections of the party walls between the buildings. This was proposed as part of a "general undertaking" by the inhabitants of Chester, dated by Hewitt as taking place between 1490 and 1520. This created a continuous passage where there had once been rooms. Hewitt's position was challenged by the arguments that the inhabitants would be giving up "to the public good, the best portion of the best room" and that the degree of co-operation needed to create the Rows in this manner would be unlikely.

The challengers felt that the rows were laid along "accumulated debris" in front of the houses and that the undercrofts were later excavated into this. Thus the Rows were never parts of separate buildings which were connected up by "knocking through". There are places where the Rows are interrupted by walls "enclosing" a section of them and while Hewitt would probably argue that these are a survival of the pre-Row structure, there is ample documentary evidence to show that these enclosures only came about after the Rows had been established for some time.

In 1894 Cannon Rupert Morris published his work on Tudor Chester which added documentary evidence into the mix and showed that the rows were mentioned in the 1330's (pg. 292). His book is often overlooked in favour of the more popular guidebooks but is well worth a read. Morris (pg. 270) devotes a few pages to the pavements of Chester and mentions how iron grates were installed at the foot of "greeces" and stairs leading (presumably) to the Row level walkway. It is possible such grates provided a barrier to the transfer of "filth" from the unpaved streets to the Rows walkway, and may even have have hindered domestic animals, such as pigs, from reaching the Rows. One minor isssue with Morris is that he tends to sometimes take anything written in older sources as truth. However he does usefully point out that Gerald of Wales does not mention the Rows:

- "As to the antiquity of the Rows, we must take into account the devastating fires in 1140, when the whole of the city was destroyed, and in 1180 when the same fate was only averted by the carrying in procession of St. Werburgh's shrine, and the great Minster of St. Michael perished ; and in 1278 when almost all Chester, "fere tota Cestria" was burnt down. The Rows could not have been earlier than the latter date. As bearing upon this, it is noteworthy that Giraldus Cambrensis, who lived 1147-1220, makes no mention of the Rows.."

Since then the study of the Rows has concentrated on both the architectural evidence and on documents, but both of these are somewhat scant. Even as recently as 1902 some were again suggesting that the Rows were directly derived from Roman collonades although quite how these survived into Medieval times was never explained. Perhaps the earliest reference to the Rows that has been found is from 1267 (some ten years before the date of the supposed Great Fire) when Roger the barber was granted a house on the site of the Pied Bull, Northgate Street, in “le Lorimersrowe”. However, it is not at all clear that that this reference to a "rowe" is a reference to a row in the sense of a galleried structure.

Until the 1950's and the work of Lawson and Smith the explantions of the Rows were a mix of these early theories. Lawson and Smith recognised that the lack of anything similar elsewhere had left the origin of the Rows, in terms of their purpose and date unexplained and concluded that there were two clusters of likely explanations for the Rows. Their paper is well worth reading as it refers to and provides plans of some buildings which have since been demolished.

Smith argued a fixed date for the origin of the Rows whereas Lawson submitted a case for an earlier and more protracted development. Both agree that the frontages of the Anglo-Saxon and medieval streets are related to the Roman street plan but do not in places follow them with particular precision. For example, Watergate Street is probably narrower than the corresponding Roman street as it was closer to the port as development was more intense. They both support the view that the underlying ruins of Roman buildings helped to establish the level at which the row level was constructed and note that the floor levels of two of the oldest churches, St Peter and St Michael are five feet and four feet respectively above the modern roadway. They place the modern road level a couple of feet higher than what would have been the road level in Roman times. Neither author argues that the Rows are some form of survival of Roman collonades.

These explanations go some way towards solving some of the difficulties as regards the interpretaion of the Rows, but really only show that something called "Rows" were in existence in the late 1260's. It is perhaps notable that Lucian the Monk, writing around 1200 does not mention the Rows in his description of Chester. The nature of Lucian's work is such that, if the Rows existed when he was writing, he would have almost certainly have mentioned them. The current consensus is that the Rows emerged gradually between c. 1200 and 1350 through the adaptation of a common form of urban domestic building, the split-level house with an undercroft, to the unusual circumstances present in the centre of Chester, in particular the difference in height between street frontage and the rear aspect. The current theory holds that for external access the buildings required substantial stairways which projected inconveniently into the highway and darkened the narrow frontages which gave the undercrofts their sole source of light. The Row walkway provided a means of limiting the number of stairways from the street without restricting access to the first-floor premises.

There is some evidence, mostly from names, that the earliest Rows were linked with a single trade. For instance, Butchers Row could be found at Watergate Street, Mercers Row and Shoemakers Row were based on Bridge Street (but the latter moved to Northgate Street), Cornmarket Row was located at Eastgate Street, near to Bakers Row and Northgate Street was home to Ironmongers Row. That suggests that they may have owed something to the co-operation of members of the same craft, a process easier to secure in Chester than elsewhere because of the persistence there of a guild merchant covering all the trades and acting as a governing body for the whole city. Clustering of trades might seem detrimental due to increased competition, but had advantages in the sharing of "inside" commercial information and would allow for arrangements such as "price-fixing". Related families in the same trade could also share burdens such as security, and gossip.

The government of Chester was somewhat peculiar in that while the city had been an important seat of Mercian power and had a line of Norman Earls of Chester, the line of the Earls failed with John Canmore and the Earldom became a possession of the Crown under Henry III. Thereafter the Earldom typically passed to the King's son. There were effective gaps in this line of sucession at times when the monarch had no son or when the son was a minor. Thus, there was no "local" magnate in semi-permanent residence. Matters were further complicated by the relations between the City of Chester and the Palatinate which developed out of Earl's Cheshire holdings. Chester was a major port and its economy was largely based on trade, hence the emergence of a guild-led governance model comprising the "Assembly" led by a mayor elected by a body of Aldermen. A major concern of the Assembly was the preservation of their local trading privileges, the regulation of this trade and the exclusion of "foreigners". This had a repressive effect on growth and may have hindered the redevelopment of commercial premises.

A related factor to the control of trade by the guilds, was the cooling effect on the growth of trade by the decline of the port of Chester. This was due to several factors, including the silting of the River Dee and its unsuitability for increasingly larger vessels. While excellently placed for the "Irish Sea Zone" and trading with the Biscay coast (including Gascony, with its "bastides"), Chester was not well-placed to trade with the rest of Europe. A glance at maps of Chester shows that the city did not really outgrow the City Walls until quite a late period. There are a plurality of possible influences on why trade establishments did not need to multiply and these could well have played a part in the survival of The Rows.

Edward I

Prince Edward (later Edward I) became "Lord of Chester" in c.1254 at around the age of 15. This was a part of a series of grants to Edward at the time of his politically motivated wedding to Eleanor, the half-sister of King Alfonso X of Castile. The event is wonderfully confused in the sculpture at the Town Hall which has the future Edward I as "Prince of Wales" in 1254. The events of 1254 involved English fears of a Castilian invasion of the still English-held province of Gascony of which Edward had been made duke. Edward would have been familiar with the "bastides" of Gascony.

Edward was soon having trouble with the Welsh. Hemingway suggests that this was in part due to the treatment of the Welsh by Edward's own appointee:

- "the Welsh under Llewlyn ap Gryffyd, made a powerful interruption into this neighbourhood, where they committed great ravages, carrying fire and sword to the very gates of the city, and destroying everything around on both sides of the river. This hostile attack was inflicted for the cruelties perpetrated on the Welsh by Geoffrey Langley, lieutenant of the county under prince Edward." (Hemingway)

Hemingway, as usual, does not give his sources. Very little is known about a Geoffrey (of) Langley who could have lived 1216-74, but we do know something of relations with Wales at the time. Llewlyn ap Gryffyd (who would eventually be recognised as Prince of Wales) had been forced to accept the Treaty of Woodstock in 1247 which restricted his territory to west of the Conwy. Trouble flared-up when Dafydd ap Gruffydd came of age, King Henry accepted his homage and announced his intention to give him part of the already reduced Gwynedd. Llywelyn refused to accept this and Owain Goch ap Gruffudd and Dafydd formed an alliance against him. This led to the Battle of Bryn Derwin in June 1255. Llywelyn defeated Owain and Dafydd and captured them, thereby becoming the sole ruler of Gwynedd Uwch Conwy. Llywelyn now looked to expand his area of control. The population of Gwynedd Is Conwy resented English rule. This area, also known as "Perfeddwlad" (meaning "middle land") had been given by King Henry to his son Edward and during the summer of 1256, he visited the area but failed to deal with grievances against the rule of his officers. An appeal was made to Llywelyn, who, that November, crossed the River Conwy with an army, accompanied by his brother, Dafydd, whom he had released from prison. By early December, Llywelyn controlled all of Gwynedd Is Conwy, apart from the royal castle at Dyserth, as a reward for his support and dispossessing his brother-in-law, Rhys Fychan, who supported the king. An English army led by Stephen Bauzan invaded to try to restore Rhys Fychan but was decisively defeated by Welsh forces at the Battle of Cadfan in June 1257, with Rhys having previously slipped away to make his peace with Llywelyn and Bauzan being killed in the battle.

Edward himself would visit Chester in 1256 (on his way to Wales) and was there several times in the next few years, mostly organising raids on Wales. These early campaigns of Edward in Wales were cut short after 1258 when Henry III and Edward had to return to England to deal with the growing crisis with his barons, that would eventually develop into the Second Barons' War (1264–1267). A further complication at the time was an "unusual famine" probably caused by the 1257 Samalas eruption.

Edward I would resume and complete his conquest of Wales around 1277. As mentioned above, the "Great Fire of 1278" comes from a single line in the Chester Chronicle which tells us that "almost the whole of Chester within the walls of the city was burned down on May 31st". There is no other evidence for this fire which came at a critical stage in Edward's consolidation of his conquest of Wales. Chester had played an important part in this. The same year saw the death of John Arneway, mayor of Chester from 1268 to 1278. Arneway is associated with Crabwall Manor and was one of the two early mayors (the other being Richard the Clerk) who enjoyed their positions for multiples of years and probably had a major influence on Chester in the third quarter of the 13th century. It is possible that the decade of seemingly stable administration under Arneway could have provided the environment in which the Rows could develop.

Dendrochronology

Dendrochronology (or tree-ring dating) is the scientific method of dating tree rings (also called growth rings) to the exact year they were formed in a tree. The width of tree rings varies with the weather in any particular year, being sometimes wider and at other times narrower. A chronology can be built=up from many different samples of wood to form a continuous database which can be anchored by reference to other sources of dating. While archaeologists can date wood and when it was felled, it may be difficult to definitively determine the age of a building or structure in which the wood was used; the wood could have been reused from an older structure, may have been felled and left for many years before use, or could have been used to replace a damaged piece of wood in an existing structure.

Some dating of this type was performed as part of the "Chester Rows Research Project" in the 80's/90's. The wood used in the Rows was almost always oak and the seasoning period for building timber was short, so it was often used "green". Complications in the dating process arise when the sample does not contain the outermost (i.e. last) tree rings, but the process does enable the identification of the earliest time at which a tree was still growing. Estimated felling dates for older wood at 36 Bridge Street range from after 1267 to after 1336. Timbers at The Falcon have felling dates ranging from 1199 to 1233. Wood from the early parts of Booth Mansion had felling dates ranging from after 1220 to after 1267.

These dates possibly provide a date for the origins of the Rows around the lifetime of Edward I (June 1239 – 7 July 1307), during the reign of Edward II (1308-1327) or in the early reign of Edward III. This fits with the theory that the Rows are somehow associated with the Edwardian conquest of Wales. Edward I constructed the so-called "Ring of Iron" after the end of the war in 1282 and they were the work of master architect James "of Saint George". Most castles were built with an integrated fortified town, as can still be seen at Conwy, Denbigh and Flint.

Chester, with City Walls and Chester Castle was an excellent base for the conquest and as mentioned above there is a view that the vast numbers of workers involved in the building of castles spent the winter in Chester and were available for the construction of the Rows. There is however no conclusive evidence that this was the case and that Edward I was in any way "responsible" for the Rows.

Further Evolution

"Land" ownership on The Rows rapidly became complicated, as row level and street level ownership could be separated, as could the ownership of the "shop" and the town-house behind it. A deed dated at Chester, "on the morrow of the Feast of St. Mary Magdalene, 15 Edward III", (A.D. 1342) reads:

- "This Indenture made between Felicia de Donecastr on the one part, and William the son of William de Donecastr on the other part. Witnesseth that whereas the said William holds a cellar in the City of Chester, in Northgatestrete, and the said Felicia holds the shop next above, and the said William the room (soler} above the said shop. It is agreed between the said parties and the said William gives to the said Felicia, towards the north of the said shop, 2 ells and half an ell, quarter and half a quarter and the fourth part of a quarter in length, and half an ell in breadth, in exchange for that part which the said Felicia claims in the said cellar towards the south of the said shop and in the room above."

From the late 15th century onwards, householders enlarged their properties by extending the chamber over the Row and supporting it on posts in the street. The gap between these posts and the street side of the Row walkway was then covered, extending the stallboards. The street level shop could then also be extended, often by adding a shop front reaching as far out into the street as the stallboard above it. This encroachment, continued through the 16th and 17th centuries. In places a small shop or chamber (often called a "cabin") was even erected on the stallboard, so that the "Dark Row" thus created became a gloomy and even dangerous place. Encroachment was controlled by the City Assembly, and owners had to pay a "fine" and thereafter annual rent, because they were "taking land from the city".

It is not entirely clear how the row level shops would have functioned. One possible explanation is that the stallboard would have been used for the display of goods that would be moved indoors when the shop was closed. There would have been no glass windows fronting onto the Rows and it is possible that there was an opening which could be covered by shutters for security. The shopkeeper would probably conduct much of their business on the row level itself. In effect, the Row walkway passed through the merchant's area of commercial activity.

The late 16th and early 17th centuries witnessed a further building boom in the city. Row buildings were adapted. Medieval open halls were subdivided into chambers and large chimneys replaced the former central and open hearths. In some cases, lavishly decorated new chambers, like that in Bishop Lloyd's House, were created above the Row walkway.

Civil War

The earliest recorded enclosure of a Row was during the Civil War in 1643, when Sir Richard Grosvenor petitioned the Assembly to enclose the Row of his town house in Lower Bridge Street (now The Falcon). As a leading Royalist commander, garrisoned at Chester Castle, his request could not be denied and the Row walkway was enclosed to form a new room in the front of the house. The stone columns which once supported the upper floor and the original shop front at Row level, can still be seen in the Falcon bar. This precedent lead to the loss of almost all the Rows in Lower Bridge Street - once a section of Row has been lost, adjoining householders were able to claim that it was now useless as a public walkway.

Chester suffered enormous damage during the Civil War which required some rebuilding. Thereafter either enclosure or complete removal of the Row continued. In some instances completely new houses were constructed which did not incorporate the Row, which was considered both unfashionable and lacked privacy. One of these was Bridge House, built by Lady Calveley in 1676; it was the first house in Chester to be designed in neoclassical style, but still retained the entrance at Row level. In 1699 John Mather, a lawyer, gained permission to build a new house at 51 Lower Bridge Street, which also resulted in the loss of part of the Row. In 1728 Roger Ormes, rather than building a new house, enclosed the Row at his home, Tudor House, making it into an additional room.

Enclosures did not always block the Row entirely. In some cases the stallboard was built upon and there were complaints that shops on stallboards were a nuisance which deprived legitimate Row traders of light, created shelter for "lewd persons" at night, and were used as latrines. Nevertheless, the process remained unchecked. By 1662 the Row walkways seem generally to have been flanked by shops on both sides, and throughout the late 17th century there were frequent applications to build new shops and chambers in them. Stallboard enclosures perhaps encouraged a move away from the hall at Row level to the street chamber over the Row as the principal room in houses in the main streets. Especially fine examples survived in 2000 at Tudor House, no. 17 Eastgate Street, and Bishop Lloyd's House (no. 41 Watergate Street), the last with notable plasterwork. There was also some development of a fourth or attic storey where rooms might be furnished with fireplaces and plaster ceilings.

Thus, during the late 17th century and 18th centuries, many sections of the Rows system were lost through enclosure or rebuilding. Elsewhere, the Assembly had more success at preserving the Rows. Sir George Booth rebuilt two medieval houses in Watergate Street in 1700, but was obliged to keep the Row walkway.

Overall, between the mid 17th and mid 18th century there was enclosure of approximately a third of the walkways and their incorporation within private housing. Petitioners for enclosure often described the Rows as useless, dangerous, or seldom used, and occasionally as allowing disorder at night. The greatest losses were in Lower Bridge Street, initially on the west side where a long section, running south from Grosvenor's house to Bridge House (nos. 18–24), had disappeared by 1687. On the opposite side, enclosure began in 1700 at no. 51, and between then and 1730 there were c. 20 further petitions for Bridge Street as a whole. By the mid 18th century, when the city began to oppose complete enclosure, the Rows in Lower Bridge Street and in Watergate Street west of Crook Street on the north side and Weaver Street on the south had almost entirely disappeared. In many cases this led to some rather steep sets of stairs coming down from a "front door" at the former Row level to the street.

At times the Rows were not as clean as they are today. Daniel Defoe, writing around 1724 in "A tour thro' the whole island of Great Britain", describes the Rows of Chester as:

- “long galleries, up one pair of stairs, which run along the side of the streets, before all the houses, though joined to them, and is pretended, they are to keep the people dry in walking along. This they do effectually, but then they...make the shops themselves dark, and the way in them is dark, dirty, and uneven.”

Georgian

Requests for permission to enclose declined from the mid 18th century and virtually disappeared after 1770. Although as a result no substantial new houses were built, in the late 18th and early 19th century renewal of frontages continued. Gradually the Row walkway came once again to be regarded as a desirable feature by the Assembly. Cast-iron columns were introduced either to replace timber or provide additional support as upper storeys became more massive, and by the early 19th century Row openings were heightened when the buildings behind and above them were rebuilt. The stallboard structures (cabins), which darkened and obstructed the Rows and about which the Assembly had become concerned by the 1760s, were largely removed in the early 19th century. However there were still losses to the Rows, in 1808 Thomas Harrison designed the Commercial Coffee Room in Northgate Street in neoclassical style, with an arcade at the ground-floor level (occupied by a bank), rather than continuing the Row on the first floor. The bank was useful for those doing deals in the Coffee Room but became insolvent after only two years and in the 1960's the arcade was opened-up for pedestrian use.

Hanshall writing in or before 1816, describes how attitudes towards the rows were beginning to change. He must have been born in the later half of the 18th century:

- ..there is little doubt the streets without the wall at one time possessed these conveniences. Even within our early recollection, several rows have been destroyed. Where the Green Dragon Inn, in Eastgate street stands, were formerly a row and shops - there was a thoroughfare within these few years in the Lower Row on the West side of Bridge street, the steps of which are now taken down, and the way blocked up, - the passage of the row (called Broken-shin Row) on the East side of Northgate street, near the Theatre, is stopped. We cannot but lament that these innovations have taken place, because we are persuaded that the Rows are at once ornamental, and highly useful to the citizens; and it is still more to be regretted, that not one protecting voice was then raised on their behalf, to save them from destruction, amongst those gentlemen who had the municiple authority.

Hanshall also gives some indication of what he believed the Rows were like before the time of his writing.

- The Rows , if we may judge from the most ancient specimens now in existence, were formerly very low, not exceeding six feet, and generally not more than 5 feet 10 inches high. To the front of the street was a clumsy wooden railing and immense pillars of oak supporting transverse beams over which were built the houses, chiefly of wood, which hung over the street and in some places nearly met in centre! A little above the top of the row run heavy slated sheds, called Pentices. These are removed, and within the last twenty years, the streets have assumed a new and more pleasing appearance. Many houses have been taken down which on being rebuilt were to the street (which was made considerably higher) decorated with a neat iron railing. These improvements are becoming pretty general in Bridge street and Eastgate street: but the wooden antiquity of Northgate street and Watergate street remains unaltered, and is likely to continue so for some time. The views of the different streets as they at present stand are very ably delineated in Panoramic sketches by Mr Batenham of Chester, an artist who deserves a more extensive patronage than he receives, and whose works will one time or other become valuable to every lover of the relics of past days.

Batenham's illustrations of Chester are often overlooked as a depiction of the Rows prior to the "Vernacular Revival" of Victorian times.

The "Chester" Look

In the second half of the 19th century, Chester was transformed by the "half-timber" or Vernacular Revival. The reasons why this revival took such a firm grip of the architecture of Chester are not entirely clear. Some architectural historians see the revival as a response to industrialisation which could take the form of stylisic craftsmanship or nostalgic muddle. Others see it as a reaction to neo-classical formalism, for example that of Thomas Harrison.

The architecture of Chester is often referred to as "Tudor". Architectural historians distinguish several phases in true "Tudor architecture" and little of it actually involves the "half-timbering" characteristic of earlier English Vernacular Architecture. Looking at the illustrations of Batenham, which date from before revival of "Tudor" architecture, it is clear that there were still surviving elements of "Medieval" architecture in Chester. These included gable ends facing the streets, and some jettying of upper floors upon a bressummer. However, despite what Hanshall writes about how buildings "in some places nearly met in centre", there is no evidence that this was the actual case.

The movment in Chester was led by talented local architects including Thomas Mainwaring Penson, Thomas Meakin Lockwood and John Douglas. The presence of the later two being perhaps very fortunate for Chester. Many ancient buildings were "restored" or completely rebuilt in the black and white "Tudor" style and variations upon it. In most cases, the Rows were respected and improved. An exception being Shoemakers' Row on Northgate Street where the elevated Row walkway was replaced by a street level arcade. Thus, while the rows were kept, none of the "black-and-white" buildings today visible on the Rows have actually medieval facades.

Hanshall would not live to see the transformation of the Rows as he died in the Cholera Pandemic of 1833. The half-timbered revival in Chester was pioneered by the architect Thomas Mainwaring Penson (1818-64). His first building in the style was erected in 1852 in Eastgate Street and he was also responsible for the expansion of Browns' shop in 1857-8, a scheme which produced adjacent buildings of wildly differing styles, one proto-vernacular revival and the other 13th-century Gothic.

Another clash of styles can be seen in Bridge Street: Number 49 is a Vernacular Revival building by W M Boden, dated 1891 on the gable tie-beam and in a similar style to his 2-7 Upper Bridge Street. Next-door numbers 51-53 have a "proto" Vernacular Revival frontage from 1858 by James Harrison, which encases a much altered 17thC timber frame building. This building tallies with the reference to James Harrison's buildings in Bridge Street quoted from The Builder v.16 p.269, April 17 1858:

- "A shop in Bridge Street Row is also to have timber work characteristic of Chester in the fourteenth century. Mr Harrison is architect of both buildings."

At a meeting of the 31st December 1849 the Chester and North Wales Architectual, Archaeological and Historic Society was formed (James Harrison was the first architectural correspondent of the Archaeological Society) and when the minutes of this first meeting were written up and circulated they were accompanied by an anonymous article entitled "Street Architecture of Chester". The author of this piece laments the replacement of timber-framed houses "with curiously carved fantastical gables" with "miserable brick and and incongruous piles of heavy Athenian architecture". The unknown writer goes on to say:

- "..that if Chester is to maintain its far famed celebrity as one of the 'wonder cities' of England, if the great European and Transatlantic continents are still to contribute their shoals of annual visitors to ill our hotels, and the not too plenteous coffers of our tradesmen, one course only is open to us. We must maintain our ancient landmarks, we must preserve inviolate our city's rare attractions, .. our quaint old Rows, unique and picturesque as they currently are, must not be idly sacrificed at Mammon's reckless shrine."

In the earliest phase the half-timbered style was not universal, and was breached most notably by George Williams's classical stone building for the Chester Bank at the corner of Eastgate Street and St Werburgh Street. Williams and Penson, as well as James Harrison (1814-66) and to some extent Edward Hodkinson, were nevertheless instrumental in initiating the revival style in Chester, but in their work the styling lacked depth, the timbering was insubstantial, and the detailing was devoid of historical accuracy. Even Hodkinson (who actually lived in Mainwaring's Watergate Street house until its demolition in 1851) was at times no fan of the half-timbered revival - writing in the 1890 volume of the Journal of the Archaeological Society that:

- "It is much to be regretted that our fine old houses should not be restored in the spirit of their original design"

He then goes on to remark of the Old White Bear Inn in Lower Bridge Street - where a Georgian front had been over-painted in black and white to imitate timberwork:

- "...it is almost incredible that such a piece of vandalism should take place in Chester" (JCAS 1890, 324)

The next generation of architects adopted a more scholarly and disciplined approach. The dominating figures were John Douglas (1830-1911) and Thomas Meakin Lockwood (1830-1900), but others, including H. W. Beswick, James Strong, W. M. Boden, and Thomas Edwards, were also active. The work of Lockwood, a local man much patronized by the Grosvenors, was perhaps best exemplified at the Cross. In 1888 he was responsible for one of the best known groups of vernacular revival buildings in Chester, no. 1 Bridge Street, on the eastern corner of Eastgate Street and Bridge Street, and in 1892 he designed those on the opposite corner, between Bridge and Watergate Streets, a more eclectic composition with renaissance and baroque elements in stone and brick interwoven with half-timbering. During this rebuilding the Rows were often made more convenient, with better lighting, more even floors, and improved steps from the street. Many of the Victorian structures on the Rows would have been impossible to achieve using oak and plaster infil, so behind the facades there is a lot of brick and some structural steelwork.

And of course there are some real "howlers" in the Rows. One of the best (or worst) examples being Number 55 Bridge Street where just about everything is tried to make the property look like something that might be thought original, and the overall effect is to fail miserably yet in an entertaining manner. A statue of King Charles on a "Tudor" building simply isn't believable - but then again neither is Queen Victoria, who perches on "Tudor" frontage in St Werbugh Street.

Most Recent

Any present rebuilding which encloses a section of the Rows is probably unthinkable, but even modern developments which preserve the Rows are of variable quality. The block of four 1960's concrete shop units with flats above at 55-62 Watergate Street, is sometimes cited as an example of Brutalist architecture and was the winner of an architectural competition held by the then City Council (and judged by George Grenfell-Baines). It was designed by Bradshaw, Rowse and Harker of Liverpool. In the 1950's-60's this was a vacant lot which formed a notorious gap in The Rows - the Council had purchased the buildings on this site for restoration, but had done little to maintain them and by the 1950's they had fallen into such a state of dilapidation that they were demolished as dangerous structures.

The concrete "New Build" on this site may have been in keeping with its time, but rapidly became one of the issues that sparked a new debate about the best way to fit new buildings into Chester's historic streets.

Summary

The Rows of Chester are a unique and spectacular sight as well as a way of exploring, or simply getting around, the city with a dry head during inclement weather. Further investigation, both of the structure and of documentary evidence, could possibly solve the remaining mysteries of their origins, which may be due to a combination of factors unique to Chester. While it seems likely that Edward I's invasion of Wales played a part in the origin of the Rows the full details are not known.

The Rows have evolved significantly over the years: while the general layout has survived in the core area around the High Cross, much of the building structure above the undercrofts has been replaced, possibly several times and in a variety of styles. In fact, the Rows are a good showcase of many architectural styles including debatable ones such as Mock Tudor and Brutalist.

Outlying sections of the Rows in lower Bridge Street and Watergate Street have been lost to enclosure. Again, the survival of the remainder of thw Rows seems to be due to a complex set of economic and political factors. The last significant section of the Rows which was lost appears to have been that at Shoemaker's Row in Northgate Street, which existed up to about 1900.

The present manifestation of the Rows is in the form of mostly Georgian architecture with a mix of Vernacular Revival frontages whose best features were due to a relatively small group of local architects, especially John Douglas and T.M. Lockwood.

Sources and Links

Related Pages

- Architectural Glossary;

- Leche House;

- Quarters;

- Mock Tudor otherwise known as "Mockery Tudor" or "Joke Oak";

- Architects;

- Structures;

Online

- The Rows on Wikipedia;

- The Rows on Cheshire Now;

- Further details of the Rows can be found at the Briish History Online pages;

- The Rows of Chester: two interpretations: JCAS vol 45 (1958);

- The definitive guide to the Rows is "The Rows of Chester" by Dr Andrew Brown. This is the result of a ten year "Chester Rows Research Project" and is available from the Grosvenor Museum bookshop.

- Virtual Stroll reproduces the texts of Louise Rayner and Hemingway and adds some more helpful stuff.

- Changing approaches to the analysis and interpretation of medieval urban houses;

- Vernacular Revival and Ideology;