Database changes have finished applying - please report any issues you're (still) seeing to support@shoutwiki.com.

Chester and Ireland

Chester was for many centuries the most important place by far in north-western England. That was largely due to its location at the crossroads of the British Isles, where routes from southern Britain led into north Wales and the Irish Sea. On many occasions Chester's role as the point of entry into the Irish Sea region for rulers based in the South and hence a route to Ireland, made it prominent in national affairs. The effect of the Irish trade on the history of Chester has been very significant on the development of the city. The history of Ireland is a complex subject and this article focuses on the relationship between Chester and Ireland (particularly Dublin), which might not always reflect the more general relationship between England and Ireland. From a very early date Dublin was by far the main port in Ireland and most of the foreign trade passed through Chester. Holyhead's role in trade with Ireland may go as far back as 2,000 BC, when porcellanite stone axes from Ireland were an import.

In recent years historians have recognised the importance of the Irish Sea region for which Chester and Dublin were at times the major ports. The Romans may have considered an invasion of Ireland when Chester would have been conveniently located as a possible capital of the expanded province of Roman Britain. In the post-Roman period there was colonisation of the region around the Irish Sea by the Vikings and later the Normans: in both of these Chester and Dublin played an important role as they also did during the Tudor "reconquest" and the later development of trade. The Chester-Dublin route retained its importance with the development of better land communication in the form of roads and then railways.

Some historians have developed the idea of a distinct "Irish Sea Culture", with various warrior/elite or religious components. Such models can open onto complex historiographical questions.

Early Irish Sea Trade

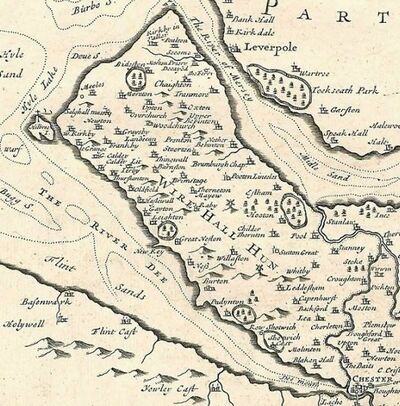

Meols, on the tip of the Wirral, was named as such by the Vikings; its original name from the Old Norse for "sand dunes" was melr, becoming melas by the time of the Domesday Survey. The dunes stretch from West Kirby to New Brighton. Strong waves and tidal currents caused the formation of offshore sandbanks. These are covered by the sea at high tide but dry out as the tide ebbs, creating areas of sheltered water in their lee. One such sheltered roadstead developed behind the Hoyle Bank, acquiring the name Hyle or Hoyle Lake. Daniel Defoe described it as follows:

- "Going down from Chester, by the Rhoodee, … and coasting the river after it is grown broader than the marshes; the first place of any note which we come to is Nesson, a long nase or ness of land, which running out into the sea, makes a kind of a key. This is the place where in the late war in Ireland, most of the troops embark'd, when that grand expedition begun; after which, the vessels go away to Highlake, in which as the winds may happen they ride safe in their way … till the wind presents for their respective voyages." (Daniel Defoe: Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain, 1724 – 1727)

Archaeological finds dating back to the Neolithic period suggest that the site, particularly Meols, was an important centre in antiquity. Since about 1810, a large number of artefacts have been found relating to pre-Roman Carthage, the Iron Age, the Roman Empire, Armenia, the Anglo-Saxons and the Vikings. These include items as varied as coins which belonged to the Coriosolites in Brittany and a silver tetradrachm of Tigranes I of Armenia, minted in Syria in the 1st century BC. Also, tokens, brooches, pins, knives, glass beads, keys, pottery, flint tools, pilgrim badges, pieces of leather, worked wood and iron tools. These finds suggest that the site was used as a port as far back as the Iron Age some 2,400 years ago, and was once the most important seaport in the present-day North West England. For thousands of years, people had made use of the natural harbour called the Hoyle Lake. This gave its name in modern times to Hoylake, the town which grew up nearby. Thus trading connections are believed to have reached far across Europe.

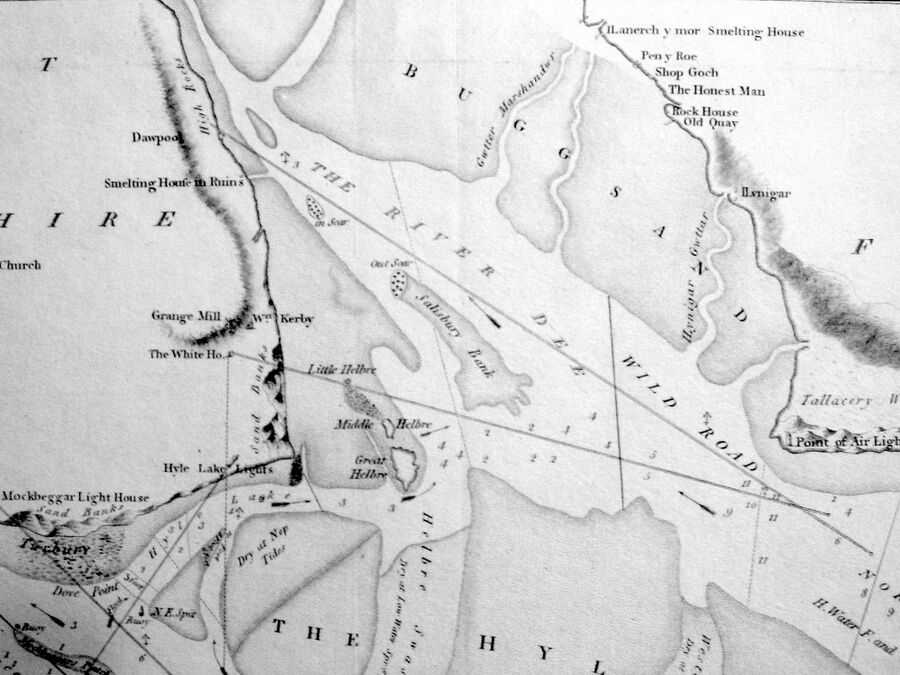

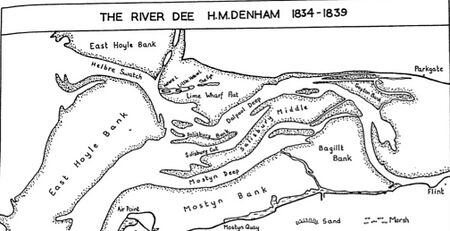

Maps of the coastline in the 18th century show a low sandy promontory, known as Dove Point (the name comes from Celtic dubh meaning black), which once existed to the north of the present coastline. This can still be roughly made out at low tide (as Dove Spit) although the modern coastline at flood-tide shows no sign of it. It was once thought that Dublin came from the same "viking" root, but is now thought that the Viking settlement was preceded by a Christian ecclesiastical settlement known as "Duibhlinn", from which "Dyflin" took its name.

From the end of the 18th century, there were major changes in the offshore channels and sand banks. Some have suggested this was partly caused by the beginnings of large-scale dredging on the approaches to the growing port of Liverpool. Others might suggest that this is in part a consequence of the canalisation of the River Dee. A third explanation is that this was a natural phenomenon where long-term climatic and erosional changes reached a tipping point. Whatever the cause, there was a sudden acceleration in coastal erosion at Meols. Throughout the 19th century, until the sea defences were completed in the mid-1890s, the Wirral coastline retreated southwards for up to half a kilometre in places. As large areas of dune sand were washed away by storms, extensive traces of ancient settlements along the coast were exposed. Patches of blackened mud with fibrous decayed wood are occasionally visible in the shifting sands. These are the last remnants of the forest which stood in late Mesolithic times in this area. As the dune sand was washed away, centuries of accumulated soil under the sand, together with middens and occupation deposits associated with later prehistoric, Roman and medieval settlements became mixed with the forest remains beneath.

In the early medieval period Meols continued as a port from which people traded with Ireland and the Mediterranean. Finds include a pottery flask, which contained holy water from the shrine of St Menas in Egypt and Byzantine coins from Turkey, dating from the 6th century AD. It is likely that little survives of ancient Meols today. The coastal erosion which revealed the objects also destroyed the settlements. The objects collected by antiquarians in the 19th century and kept in public museums form almost the only surviving evidence of what was once one of the region's most important ports. National Museums Liverpool has a small collection of material from Meols, from the collections of Joseph Mayer and Henry Ecroyd Smith. Unfortunately many objects were lost in the fire at Liverpool Museum of 1941. Other groups of objects are in the Grosvenor Museum, Chester, Warrington Museum, the British Museum, and the Williamson Art Gallery and Museum in Birkenhead.

Romans and Ireland

The precise date of the first occupation of Roman Chester by their army remains uncertain, but the potential uses to which the site could be put - a fine harbour at the highest navigable point on the River Dee, a river crossing, and a defendable position with nearby springs - were doubtless well appreciated by Rome from an early date.

The Romans possibly selected the site for their fortress of Deva in part because of its potential as a port for an assault on Ireland, which they knew as Hibernia. The Roman historian Tacitus mentions that Gnaeus Julius Agricola, while governor of Roman Britain (AD 78 - 84), entertained an exiled (and unnamed) Irish prince, thinking to use him as a pretext for a possible conquest of Ireland. At about the same time, Juvenal (Satires 2.159–160) specifically tells us, Roman "arms had been taken beyond the shores of Ireland" and there has been much debate as to what is actually meant by this comment.

Neither Agricola nor his successors ever conquered Ireland, but in recent years archaeology has challenged the belief that the Romans never set foot on the island. Roman and Romano-British artefacts have been found primarily in Leinster, notably a fortified site on the promontory of Drumanagh, fifteen miles north of Dublin - perhaps the name of the fortified promontory itself holds clues as to its Roman origin: Drumanagh has as a possible root (D)ruman, which could be a reference to Romans (however Gaelic "Droim Meánach" means "Ridge of Meanach", giving another explanation). Drumanagh has produced a number of artefacts of Roman origin, found during illegal metal detecting. These included coins dating to the reigns of Titus (74-81 CE), Trajan (98-117 CE) and Hadrian (117-138 CE), as well as Roman brooches and copper ingots. In addition, a group of burials on Lambay Island, just off the coast near Drumanagh, contained Roman brooches and decorative metalware of a style also found in Roman Britain from the late first century (this could be invasion or trade).

There may be some connection between the un-named prince and a semi-mythical Irish king. Túathal Techtmar ("the legitimate"), was the son of Fíachu Finnolach, and himself a High King of Ireland according to medieval Irish legend and historical tradition. He is said to be the ancestor of the Uí Néill (O'Neil) and Connachta (Connor) dynasties through his grandson "Conn of the Hundred Battles". Túathal is said to have been exiled from Ireland as a child, but to have returned, defeated the then king and waged extensive war. In one version his mother Eithne, daughter of the king of Alba (Scotland), who was pregnant, fled home to Alba, where she gave birth to Tuathal Techtmar. The Romans were known to use "restoration of an exile" as a pretext of invasion. For example, one reason given for the invasion of Britain in 43 CE was to reinstate Verica, the exiled king of the Atrebates.

Both Roman sites at Drumanagh and Lambay are close to where the semi-mythical Túathal is supposed to have landed. Some other archaeological discoveries inside Ireland, including Roman jewellery and coins at Tara, the midland ritual complex, and at Clogher, further support the possibility of a Roman invasion of Ireland. It has been suggested that the distribution of Roman remains in Ireland fits well with the places associated with Túathal's campaign. The traditional date of his return is 76-80 CE.

Speculating somewhat, it is notable the the unique "Elliptical Building" in Chester bears some resemblance to the ritual structures at Tara, and comes from roughly the same period as the supposed invasion by Agricola and the presence of the "prince", who may (possibly) have been Túathal, in Britain. The lead pipe from the elliptic building is dated to 79 CE and Tacitus (Chapter 24) says that in 82 CE Gnaeus Julius Agricola "crossed the sea and defeated people hitherto unknown to the Romans". While he does not specify which sea they crossed (many scholars think that Tacitus refers to the Clyde or the Forth), it should be noted that after this statement, Tacitus writes only about Ireland for the remainder of the chapter, which suggests that the people he was referring to were, in fact, the Irish. There is no evidence that Túathal was actually in Chester, but it does seem to have a contender for Gnaeus Julius Agricola's "capital" and there is the remarkable co-incidence of dates:

- 79 CE: Elliptical building lead pipe (stamped on it);

- ~76-80 CE: Túathal returns to Ireland (traditional);

- 82 CE: Agricola "crosses the sea" (Tacitus);

The Annals of the Four Masters gives the date of Túathal's exile as 56 CE, his return as 76 CE and his death as 106 CE. Geoffrey Keating's Foras Feasa ar Érinn broadly agrees, dating his exile to 55 CE, his return to 80 CE and his death to 100 CE. The Lebor Gabála Érenn places him a little later, synchronising his exile with the reign of the Roman emperor Domitian (81–96 CE), his return early in the reign of Hadrian (122–138 CE) and his death in the reign of Antoninus Pius (138–161 CE). Agricola was governor of Roman Britain from 78–84 CE.

In addition Tacitus mentions that Gnaeus Julius Agricola frequently said that Ireland could be conquered with "a single legion and a few auxiliary troops", which suggests the Romans expected some special advantage if they invaded Ireland. This could have been knowledge of local troop dispositions, geography and local rivalries, but could it also have been the presence on the Roman side of a credible claimant to the Kingship of Ireland. So could the Elliptical Building have been connected to this - a palace for a potential client king, with a design similar to the ritual site at Tara and a fountain that must have seemed magical at the time? A bauble to show Túathal the advantage of being a client of Rome?

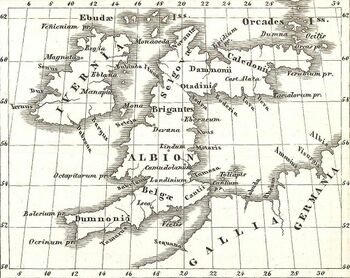

Even if there was no invasion there was almost certainly trade, as the geographer Ptolemy (c. 90 – c. 168 CE) writing in the second century made a map of "Hibernia" with reasonably accurate data on rivers, mountains and people, thereby demonstrating some considerable knowledge of the island had been gained by that time. Tacitus states that Ireland’s "approaches and harbours are known from merchants who trade there". It is likely that the Irish exchanged items such foodstuffs, woollen garments, hides, slaves and even wolfhounds.

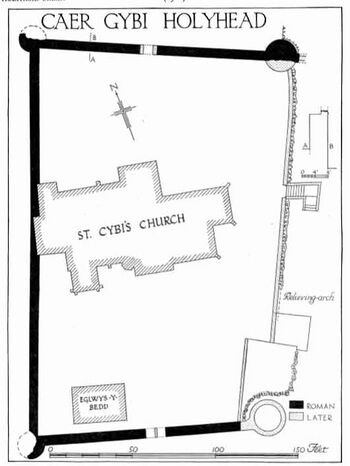

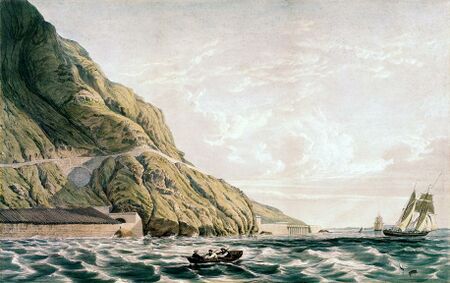

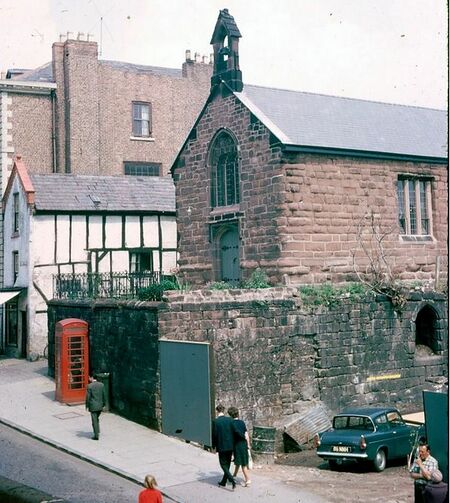

Caer Cybi

A unique Roman fortress. It is one of Europe's only three-walled Roman forts, the fourth side was protected by the sea and was probably used as a quay. The walls of the fort still stand to an impressive height - 4 metres tall - and are constructed in the distinctly Roman herring-bone style with courses of flat stone cementing the structure. The wall would originally have been topped with a parapet walk. Its date is unknown, but it is generally thought to be part of a late-4th-century scheme, associated with Segontium, which was used to defend the west coast against Irish Sea raiders. It is thought to have been "abandoned" in 393. In the 6th century, the fort was given to Saint Cybi, who used it to build a monastery.

The Church of St Cybi still stands on the site today, with a small detached chapel over Cybi's grave. There are the remains of three towers, one the North west, is mostly Roman origin and two others largely later reconstructions. The fort measured 246ft (75m) by 148ft (45m), the walls stood up to 13ft (4m) high and are 5ft (1.5m) thick. There were originally 4 towers, today there are 3, the largest is 26ft (7.9m) tall but most of this is a later rebuild. The walls are believed to have extended down to the sea and a further pair of drum towers. The fort is unique in Britain but follows the pattern of late Roman beachhead forts used to accomodate galleys and scout ships. Similar forts built under Valentinian are known along the Rhine and the Danube.

Irish Sea Culture

The religious influence of the late Roman Empire involved the conversion to Christianity of many Irish people in the century when the Western Roman Empire disappeared. Pelagius was active between about 390 and 418. He was said by his contemporaries, such as Augustine of Hippo, Prosper of Aquitaine, Marius Mercator, and Paul Orosius, to have been of Celtic British origin. Jerome possibly thought that Pelagius was Irish, suggesting that he was "stuffed with Irish porridge" (Scotorum pultibus praegravatus). The first reliable historical event in Irish history, recorded in the Chronicle of Prosper of Aquitaine, is the ordination by Pope Celestine I of Palladius as the first bishop to Irish Christians in 431 - which demonstrates that there were already Christians living in Ireland, before Palladius or Patrick. However, it may safely be concluded from the silence of Gildas that the British Church of the first half of the sixth century possessed no knowledge or tradition respecting the introduction of Christianity into Britain. Had such a tradition existed it is unlikely that Gildas would have remained silent about it.

The Roman, and therefore Saxon conception of ecclesiastical government was territorial and diocesan. The Celtic conception was tribal and monastic. In the British Isles in the 5th century, the earliest monastic communities in Ireland, Wales and Strathclyde followed a different, distinctly Celtic model. It seems clear that the first Celtic monasteries were merely settlements where the Christians lived together – priests and laity, men, women, and children alike – as a kind of religious clan. At a later period actual monasteries both of monks and nuns were formed.

The early monastic culture of Wales and that of some parts of Anglo-Saxon England were strongly connected with Ireland, to the extent that the style of the artwork from this period (c. 500–900 AD) is often referred to as "Hiberno-Saxon" or Insular. The term insular is sometimes used in a general sense for all of Britain and Ireland and sometimes for that which is due to a fusion of clear Irish and Saxon elements.

One major distinctive feature is interlace decoration, a particular example often given being the interlace decoration as found at Sutton Hoo, in East Anglia. This is now applied to decorating new types of objects mostly copied from the Mediterranean world, above all the codex or book. The large archipelago located in the north-west Britain, off the coast of Scotland among the Hebrides had for several centuries been colonized by an Irish people known as Dál Ríata who had brought with them their native Gaelic/Irish language. More recently, in the late sixth century it had become the home of a famous Irish ecclesiastic, Columba (Irish, Columcille), who established a monastery on the island of Iona, c. 570. By the time of the founder’s death Iona become a major monastery, the spiritual and intellectual center of the Irish kingdom of Dál Ríata. In the early seventh century Iona began to extend its influence to the Anglo-Saxon part of Britain. At this time it first established contacts with members of the ruling aristocracy of northern England (Northumbria) who at times took refuge there, and included Oswald Oswald's father was Æthelfrith who took part in the Battle of Chester. By the late sixth century Old Irish was being recorded in writing. It has been suggested that the alphabet first used for the writing of Old English came ready-made, not from Latin directly but from the modified Latin alphabet used by the Irish for writing their own language, Old Irish. The importance of Chester as a religious center when it was under Welsh control (around the time of Ecgbert: c.830) and as the supposed site of a synod mentioned by Bede (in 601) would have required information to be communicated along the North Welsh coastal route on or close to which there were various religious houses. Further evidence for cultural interaction between Ireland and Wales is found in legal terminology some of this has been shown to have originated in the period before the Celtic languages split up, because they are preserved both in Old Irish and in the Welsh legal texts.

As in all cases where the spread of a culture is being considered there are the extremes of wholesale movement of people, in the limiting case displacing or eradicating the original inhabitants or the spread of ideas which are adopted by the indigenous inhabitants of a new location. Often there is an intermediate case where changes (either in terms of migration or adoption) are largely limited to a ruling elite or a small class of technical specialists. The development of the Irish Sea culture provides examples of all of these processes.

Vikings and Ireland

The Vikings (or Norsemen) began carrying out raids on Gaelic Ireland in the late eighth century, and over the following few decades they founded a number of settlements along the coast. Vikings first established themselves in Early Scandinavian Dublin around 840 when they built a fortified area, or longphort, there. During the tenth century, Viking Dublin developed into the Kingdom of Dublin — a thriving town and a large area of the surrounding countryside, whose rulers controlled extensive territories in the Irish Sea and, at one time, York.

According to some writers Gaelicised Scandinavians dominated the region of the Irish Sea until the Norman era of the 12th century. They were certainly involved in the foundation of long-lasting kingdoms, such as the those of Mann, Dublin, and Galloway, as well as taking control of the Norse colony at York, but the degree of "domination" is debatable and often coloured by the views of the historian or the folklore in which the "history" is recorded.

In 902 the Vikings were thrown out of Dublin for a relatively brief period. As recorded in the Annals of Ulster:

- "The heathens were driven from Ireland, i.e. from the fortress of Áth Cliath, by Mael Finnia son of Flannacán with the men of Brega and by Cerball son of Muiricán, with the Laigin; and they abandoned a good number of their ships, and escaped half dead after they had been wounded and broken."

Many of these Vikings settled elsewhere, including one group which eventually settled in the Wirral, apparently with the agreement of Æthelflæd who was important in the development of Chester (see: Chester in 900). An Irish historical record known as "The Three Fragments" refers to a distinct group of settlers living among these Vikings as "Irishmen". Further evidence of this Irish migration to Wirral comes from the name of the village of Irby in Wirral, which means "settlement of the Irish", and St Bridget's church at West Kirby, which is known to have been founded by "Vikings from Ireland". Other nearby towns and villages with the Viking "by" suffix in their name include Frankby, Greasby and Pensby. A recently re-identified group of iron weapons in the antiquarian collections, including a sword, a deliberately-bent spear head, an axe and a shield boss, suggest the presence of at least one high-status pagan Viking grave at Meols.

Some historians have suggested that allowing the Vikings to settle in the Wirral was a strange decision. What may be relevant is that Æthelflæd's brother, Edward the Elder had other issues with the Vikings at the time. Becoming king was not straightforward for Edward upon the death of his father Alfred the Great. A cousin, Æthelwold, disputed the succession and seized the royal estates of Wimborne, symbolically important as the place where his father (Æthelred I) was buried, and Christchurch, both in Dorset. Edward brought an army to Dorset, but Æthelwold fled to Viking-controlled Northumbria, where he was accepted as king - although it is not clear whether he was accepted as "king of Northumbria" or simply recognised as having a claim to the kingship of Wessex. No explanation can be offered as to how he came to be on apparently friendly terms with the Northumbrians. In 901 or 902 Æthelwold sailed with a fleet to Essex, where he was also accepted as king (again it is not clear of what). The following year Æthelwold persuaded the East Anglian Danes (Vikings) to attack Edward's territory in Wessex and Mercia.

At about the same time that Edward the Elder was involved in the succession dispute that the Hiberno-Norse exile Ingimund sought to settle near Chester. Ingimund was a Viking who had been expelled from Ireland and had attempted to settle in north Wales where he came into immediate conflict with the Welsh. According to the Welsh Annals, Ingimund came to Anglesey and held "Maes Osmeliaun", whilst the Welsh vernacular chronicle reports that Ingimund held "Maes Ros Meilon". The site itself appears to have been located on the eastern edge of Anglesey, perhaps near Llanfaes (effectively the later site of Beaumaris) if the aforesaid place names are any clue. Another possibility is that Ingimund was settled near Llanbedrgoch, where evidence of farming, manufacturing, and trading has been excavated at a Viking-age settlement. There is reason to suspect that the Llanbedrgoch site formed an aristocratic power centre, and that it may have originated as an informal Viking trading centre just prior to Ingimund's attempted colonisation. The centre itself could have provided an important staging post between the Welsh and other trading centres in the Irish Sea region. The conflict with the Vikings is well-attested in the Welsh records but Ingimund's subsequent move to the Wirral is only based on fragmentary evidence, in Irish Annals. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, as usual, hardly mentions anything that the Mercians did.

There is no reason to suppose that the events on the Wirral and in East Anglia were related, but any arrangements reached with Ingamund could have been affected by the threat from Danes on two fronts, and the close timing of these two events is often overlooked by historians. The later fortunes of Ingamund's people is not entirely certain: there was a sizeable Scandinavian "ghetto" in the southern quarter of Chester later on, centred on the church of St Olave’s (the Norwegian king, Olaf Haraldsson, martyred in 1030), and it would appear that many of them settled down in the city as merchants, possibly giving rise to the Gloverstone enclave.

The Vikings return to Ireland

Some of the settlers in the Wirral may have returned to Dublin - in 917, Sitric Cáech and his kinsman Ragnall ua Ímair sailed separate fleets to Ireland where they won several battles against local kings. Sitric successfully recaptured Dublin and established himself as king. Over time, the settlers in Dublin became increasingly Gaelicized. They began to exhibit a great deal of Gaelic and Norse cultural syncretism, and are often referred to as Norse-Gaels.

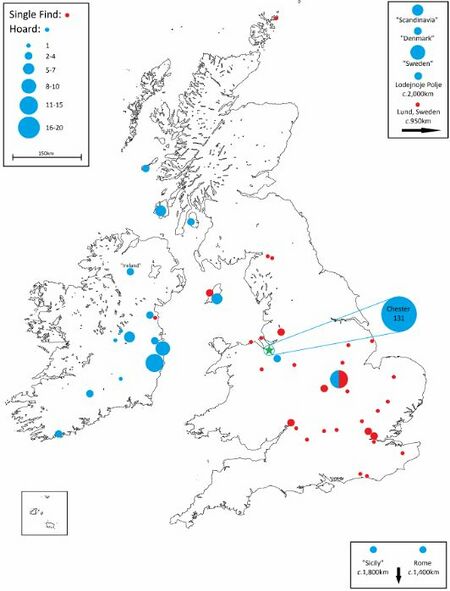

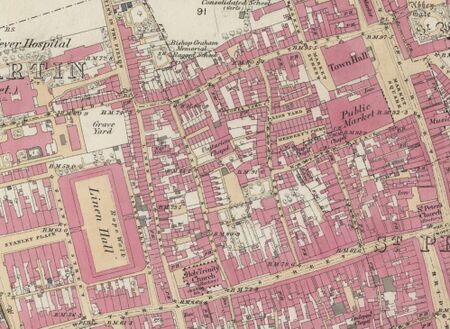

In the 10th century the reoccupied fortress at Chester became the centre for attempts by English kings to dominate other rulers around the shores of the Irish Sea, notably in the carefully staged set-piece by which King Edgar demonstrated his overlordship by having them row him on the Dee from Edgar's Field in 973. Tribute in silver extracted from such rulers was turned into coin at Chester, whose mint was astonishingly prolific in the 10th century. In addition there may have been a local source of silver at the lead mine on Halkyn Mountain, although no convincing archaeological evidence in the form of trace-element analysis linking Chester-minted coins to North Welsh silver or archaeological evidence for silver production at Halkyn Mountain has yet appeared.

During the reign of Æthelstan (924-39) the mint of Chester was the most productive in England (Blunt 1974:98) and it continued to produce coins on a scale rivalling London until the 970's. In this period of high production, large quantities of silver coin minted at Chester occur in hoards across the Irish Sea region. The context of these hoards and their mixed content often suggests that they represent the proceeds of trade rather than plunder. This flow westwards "points strongly towards trading activity via Chester". It has been noted that Chester coins are the most numerous English issues in Irish tenth-century coin hoards, although coins as a whole only comprise a small proportion of the total silver in Ireland in the tenth century.

The reign of Æthelstan saw the Battle of Brunanburh which possibly took place on the Wirral in 937. The combatants are identified as the people of Wessex and Mercia on one side, led by King Æthelstan and his brother Edmund. The enemy is identified as Constantine king of the Scots, whose son was killed in the conflict and Olaf, king of Dublin. The battle is described as a heavy defeat for Æthelstan’s enemies. Olaf fled with a small band of followers and Constantine escaped home to Scotland while the departure of the ships of Northmen to Dublin from "Dingesmere" is also reported. Although the location of the battle has been the subject of much debate. Dublin and Chester were the wealthiest ports in the Irish Sea region in this period with a regular trade between them, taking advantage of a well-established sailing route along the north Welsh coast minimising the dangers of sailing across a large stretch of the Irish Sea. Irish Sea trade is also evidenced at Meols on the tip of the Wirral. An army meeting on the Wirral would have access to a secure and efficient maritime supply line from Dublin to meet their needs before battle and to provide for an onward campaign, had the invaders been successful.

By the mid 10th-century, Chester exported things like salt, for the preservation of fish and the treatment of hides, cloth, metalwork and slaves to Dublin. Dublin exported goods like furs, hides and fish to Chester. Marten fur, a precious commodity due to its associations with royalty, was a high-value item and prized export in Dublin and marten furs made there way into Chester in this time.

It is thought that the Dublin-Leinster army in the 1014 Battle of Clontarf may have included troops from the Duchy of Normandy. At this point Dublin was a major port. The traditional view is that the battle ended a war between the Irish and Vikings by which Brian Boru broke Viking power in Ireland. However revisionist historians see it as an Irish civil war in which Brian Boru's Munster and its allies defeated Leinster and Dublin, and that there were Vikings fighting on both sides.

Cnut won the throne of England in 1016 in the wake of centuries of Viking activity in northwestern Europe. Given that it would be impractical for societies to spend this entire period engaged in warfare, trade between Ireland and Chester probably continued for much of it. Evidence from coin finds suggests that the Vikings may have been intermediaries in this trade and indicate an active mint at Chester: the Bryn Maelgwyn hoard contains coins minted by both Cnut and Hiberno-Norse King of Dublin Sihtric Olafsson: 203 Cnut silver pennies (minted at Chester) and just two Sihtric silver pennies. Society was complex enough for there to be issues over taxation, religious dialog and some record keeping.

Edward the Confessor returned to the English throne in 1042 and restored the rule of the House of Wessex after the period of Danish rule since Cnut conquered England in 1016. Edith of Wessex, sister of the later Harold II married Edward the Confessor in 1045: she was educated in several languages including Latin, French, Danish and Irish: the last being the the "lingua franca" of the Irish Sea region.

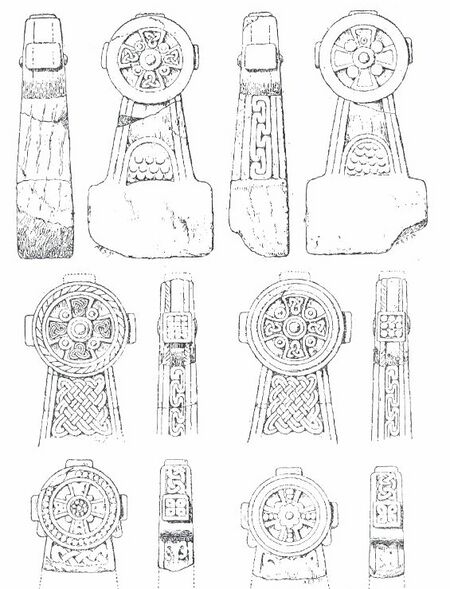

The "ring-cross head" design developed in the Celtic west and was first brought to England by Hiberno-Norse settlers in the early years of the tenth century. It remains arguable as to which of the various Celtic lands was the ultimate source of the English versions, though the western isles of Scotland have as much claim to have pioneered ring-headed forms as the Irish and Manx source. The Cheshire circle head group is geographically limited to the Wirral and Chester, with an outlier across the Mersey estuary at Walton on the Hill. Neston provides another certain example. While the precise shape is a north-west England invention, it may owe some of its details to Irish inspiration. The so-called "Cross of the Scriptures" at Clonmacnoise shows a closely comparable form in existence in Ireland in the ninth or early tenth century. St Barnabas Churchyard Cross at Bromborough is of a similar type and is associated with Æthelflæd.

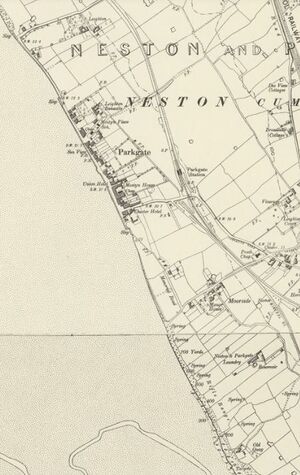

By far the best collection of ring-head crosses is that at St Johns. Investigations into relative sea levels through time have documented significant variation in sea levels in the Irish Sea basin and its major river estuaries – including the Dee – in the post-Roman period, with a marked rise from the seventh century to a peak in the later pre-Conquest era and a fall again from the thirteenth century to the present day. Those falls in sea level contributed to gradual impacts on the viability of Chester as a sea port in later medieval times, to the development of successively more distant down-stream alternatives at Portpool, Neston and Parkgate, to the silting and reclamation of the Roodee, and to major engineering and expenditure on canalising the lower reaches of the river. The early medieval sea rise, coupled with the loss of the Roman bridge serving the main road from Chester south and standing at approximately the point where its medieval successor stands, opened up the possibility of riverside landing facilities of a sort typical of the age further upstream and above the Chester "gorge": at the strand below St John’s.

In a paper by Paul Everson and David Stocker, it was argued that Edgar’s voyage on the Dee in 973 can be read as a very public confirmation of his intention both to promote Chester’s market as a commercial hub for Irish Sea trade, to service that market with his reformed coinage, and to protect its alien traders as overlord of the city. Representing Chester’s early merchant community, the authors proposed that St John’s ‘exceptional’ collection of monuments offer confirmation that Edgar’s trade initiative was "so much more than a whimsical regatta".

Late Anglo-Saxon age Ireland

In 1051 a civil war almost broke out in England. Godwin marched on Gloucester where Leofric of Chester was leading the kings forces but a war was averted when it was agreed that the Witan would sort out the dispute. The earls of Chester (Leofric) and Northumbria (Siward) remained loyal to Edward the Confessor and the Witan eventually declared that Earl Godwin and all his sons had five days to leave England. Godwin and his sons, Tostig and Gyrth, went to Flanders. Harold went to Ireland and spent the winter with Dermont, king of Leinster. For more on this see: Harold's family.

The following year Harold sailed from Dublin with nine ships, came ashore at Porlock in Somerset and plundered the neighbourhood. He then joined up with his father and brothers and sailed up the Thames. The King summoned the northern earls, and whilst Ralph (the timid) of Hereford and Odda responded, Leofric of Chester and Siward (of Northumbria) were noticeable by their absence. King Edward the Confessor was forced to seek terms.

Ælfgar, the son of Leofric, himself was (perhaps wrongly) banished around 1055, and also fled to Ireland, where, just like Harold, he also found forces to assist his return. The speed with which he is able to do so makes clear that strong political, and therefore trade, links between Ælfgar and those from whom he was able to draw support were already in place before his expulsion. Holinshead writes as follows:

- About the same time K. Edward by euill counsell (I wot not vpon what occasion, but as it is thought without cause) banished Algar the sonne of earle Leofrike: wherevpon he got him into Ireland, and there prouiding 18 ships of rouers, returned, & landing in Wales, ioined himselfe with Griffin the king or prince of Wales, and did much hurt on the borders about Hereford, of which place Rafe was then earle, that was sonne vnto Goda the sister of K. Edward by hir first husband Gualter de Maunt. This earle assembling an armie, came forth to giue battell to the enimies, appointing the Englishmen contrarie to their manner to fight on horssebacke, but being readie (on the two & twentith of October) to giue the onset in a place not past two miles from Hereford, he with his Frenchmen and Normans fled, and so the rest were discomfited, whome the aduersaries pursued, and slue to the number of 500, beside such as were hurt and escaped with life. Griffin and Algar hauing obteined this victorie, entered into the towne of Hereford, set the minster on fire, slue seuen of the canons that stood to defend the doores or gates of the principall church, and finallie spoiled and burned the towne miserablie.

"Griffin" here is Gruffydd ap Llywelyn. The rather hopeless defender of Hereford is known to history as "Ralph the timid". He was actually a Norman: Ralph de Mantes, Edward the Confessor’s nephew by his sister Goda. Ralph’s Norman-style English cavalry forces were destroyed, with Ralph earning the insulting nomenclature of ‘Timid’ for running away with his Norman retainers and leaving his men to be slaughtered. Having seen Hereford trashed King Edward raised an army and placed Harold Godwinson in command of it. Once again all-out civil war was avoided. It seems highly unlikely that Ælfgar would have sailed to Wales unless he was moderately sure of being received peacefully. The ability to generate support from across both sides of the Irish Sea is an important component of Ælfgar’s narrative.

In late 1063 or early 1064, Tostig had Gamal son of Orm and Ulf son of Dolfin assassinated when Gamul visited him under safe conduct. Gamul may have been of Viking stock. There has actually been a suggestion that Gamul was a member of the same family of the Gamul's of Chester, who lived at Gamul House, opposite St Olave. Another death at the time (in 1064) was that of Gospatric. The latter assassination has been pinned on Queen Edith, Tostig’s sister, and she was accused at court of having ordered this killing in her brother’s interest. Edith was the only senior member of the Godwin family to survive the Norman conquest on English soil, the sons of Harold having fled to Ireland. She died at Winchester on 18 December 1075.

Normans and Ireland

After the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, the Normans became aware of the role Ireland played in providing refuge and assistance to their enemies. Following the crushing defeat of the English at the Battle of Hastings, three of Harold Godwinson’s adult sons by his common law wife – Godwin, Edmund and Magnus – sought refuge in Ireland at the court of the family’s old sponsor, the king of Laighin and his aristocratic kin. They may have been proceeded by Harold’s legal wife, Edith of Mercia, the possible if unproven mother of his infant son and likely heir, also named Harold (see: Harold's family). With Diarmaid’s support Harold's sons organised several unsuccessful seaborne expeditions from the Scandinavian-Irish towns of Dublin and Wexford to liberate England, raiding some distance into the south-west of the country in the summers of 1068 and 1069 to the great alarm of the new and still insecure Norman-French occupiers. The Normans also contemplated the conquest of Ireland. It is recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle that if William the Conqueror had lived for two more years (until 1089) "he would have conquered Ireland by his prudence and without any weapons". William's son, William II, is stated as having said:

- "For the conquest of this land, I will gather all the ships of my kingdom, and will make of them a bridge to cross over".

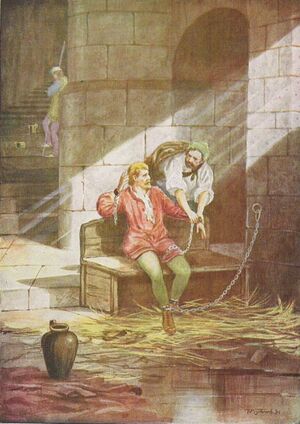

Gruffudd ap Cynan (c. 1055 –1137), was King of Gwynedd from 1081 until his death in 1137. In the course of a long and eventful life, he became a key figure in Welsh resistance to Norman rule, and was remembered as King of all the Welsh and Prince of all the Welsh. Through his mother, Gruffudd had close family connections with the Norse settlement around Dublin. He was born on the family estate north of the Liffey at "Baile-Griffin" (modern-day Balgiffin) and he frequently used Ireland as a refuge and as a source of troops. He would even survive being imprisoned at Chester Castle by Hugh of Avranches for many years (some say ten, others 12, others 16):

- ... put him in the gaol of Chester, the worst of prisons, with shackles upon him, for twelve years (History of Gruffudd ap Cynan)

He three times gained the throne of Gwynedd and then lost it again, before regaining it once more in 1099 and this time keeping power until his death. Gruffudd laid the foundations which were built upon by his son Owain Gwynedd and his great-grandson Llywelyn the Great.

The extension of the Anglo-Saxon burh system into the coastlands of the Irish Sea was arguably one of the most important events in the history of the Celtic West. The complex relations between the English, the Welsh and the Scandinavians (if indeed such simplistic 'national' terms can be used) are shown to have mediated social change, economic development and urbanism. The ruling elites around the Irish Sea evidently had close ties and at times would grant aid, especially refuge and military aid to exiles. The Fragmentary Irish Annal 429 begins in 907 and abruptly ends in 914 and concerns the Norwegians in Britain and their encounters with Æthelflæd. Like other alternative, non-canonical, sources, Æthelflæd’s agency is direct and active. At signs that the Danes were amassing in Chester:

- “The Queen then gathered a large army about her from the adjoining regions, and filled the city of Chester with her troops.”

According to the Three Fragments, she directed fortresses against the Irish-Norwegian leader Ragnald, whom she met in battle in 918 where “her fame spread abroad in every direction.” The Queen “holds authority over all the Saxons” and she specifically requests Irish help in defeating the Danes at Chester.

Summary: Chester and Dublin before the 1170's

There are no surviving detailed records of early trade between Chester and Dublin, but there is evidence of the existence of strong cultural connections. These include some traces of Roman trade, coin evidence and other physical artifacts. Other cultural connections include the presence of Vikings and their artifacts in both Chester and Dublin and the links between the political elites in Mercia, North Wales and Dublin, especially when it comes to exiles. Irish annals record events associated with Chester, particularly those assocated with Æthelflæd. Cross manufacture in Chester is of a Celtic style. There is a flow of coinage from the Chester mint to Ireland and many of the moneyers at Chester seem to have Scandinavian names. Notably Domesday has Chester producing annual taxes of £45 in pounds of silver and 125 pine marten pelts, together with an additional income from the mint in the time of Edward the Confessor. The silver and the pelts may have been associated with the Irish trade.

Henry II

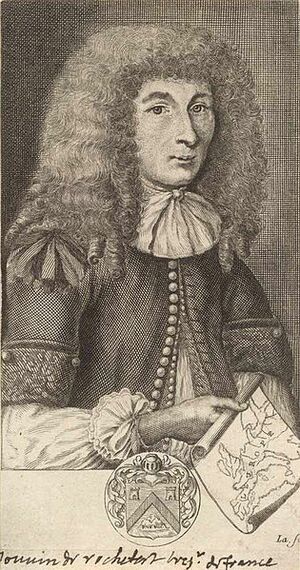

In the 1120s the historian Henry of Huntingdon regarded Chester's distinct attribute as being "near to the Irish" (not the Welsh). At the time, Gaelic Ireland was made up of several kingdoms, with a High King claiming lordship over most of the other kings. Although the earlier Norman kings have made vague comments about Ireland it was to be Henry II whould would first invade.

First, Henry secured the approval of the Pope. Laudabiliter was a bull issued in 1155 by Pope Adrian IV, the only Englishman to have served in that office. The bull is quite specific to Ireland:

- "You have indeed indicated to us, dearly beloved son in Christ, that you wish to enter this island of Ireland, to make that people obedient to the laws, and to root out from there the weeds of vices, that you are willing to pay St. Peter the annual tax of one penny from each household, and to preserve the rights of the churches of that land intact and unimpaired."

Existence of the Papal bull giving the English the right to invade Ireland has been disputed by scholars over the centuries; no copy is extant but scholars cite the many references to it as early as the 13th century to support the validity of its existence. The bull purports to grant the right to the Angevin King Henry II (ruled 1154-1189) to invade and govern Ireland and to enforce the Gregorian Reforms on the semi-autonomous Christian Church in Ireland. Henry would do nothing about Ireland for the next 14 years.

In May 1169, Anglo-Norman mercenaries landed in Ireland at the request of Diarmait mac Murchada (Dermot MacMurragh - the great-grandson of Dermont, king of Leinster), the deposed King of Leinster, who sought their help in regaining his kingship. Diarmait had been an early supporter of Henry II, who sanctioned this military intervention. The mercenaries achieved a reconquest within weeks and raided neighbouring kingdoms. In return, Diarmait had sworn loyalty to Henry and promised land to the Normans. The Norman invasion was a watershed in Ireland's history, marking the beginning of more than 800 years of direct English and, later, British, conquest and colonialism in Ireland.

The Norman takeover at Chester in 1069 apparently did not cause a major discontinuity in trading contacts. Conditions of trade in the Irish Sea changed only gradually, and the Hiberno-Norse towns of Ireland did not lose their commercial independence until after the Norman Conquest of Ireland in the 1170's. Two sources in particular refer to the port and trading activity at at Chester. William of Malmesbury, writing in the second quarter of the twelfth century, noted a deficit in the production of corn in the Chester area. Although there was no lack of beasts and fish, grain had to be imported from Ireland. Lucian the Monk echoed Malmesbury's assertion that there was trade in considerable bulk commodities with Ireland, Wales and England (meaning central and southern England). Meat (cattle and horses) and sheep were obtained Britonum (Wales), fish ex insula Hibernoram (Ireland) and corn ex provincia Anglorum.

In 1170, there were further Norman landings, led by the Earl of Pembroke, Richard "Strongbow" de Clare. The event is mentioned in the Annals of Chester for that year, together with the birth of Ranulf de Blondeville. They seized the important Norse-Irish towns of Dublin and Waterford, and Strongbow married Diarmait's daughter Aoífe. Diarmait died in May 1171 and Strongbow claimed Leinster, which Diarmait had promised him. Led by High King Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair (Rory O'Conor), a coalition of most of the Irish kingdoms besieged Dublin, while Norman-held Waterford and Wexford were also attacked. However, the Normans managed to hold most of their territory.

The island of Ireland was itself claimed as an Ecclesiastical fief, via the forged, mid 8th century, Donation of Constantine, with the feudal Lordship of Ireland later leased to Henry II of England and his heirs, by Pope Alexander III's, 1171 grant, resulting in the presence and settlement of Irish traders and seamen in English and Welsh ports. The "donation" has a long history, but for present purposes it neglects to note that the Romans never actually conquered Ireland.

In October 1171, King Henry II landed with a large army to assert control over both the Anglo-Normans and the Irish. This intervention was supported by the Roman Catholic Church, who saw it as a means of ensuring Irish religious reform, and a source of taxes. Henry was in Dublin between November 1171 and February 1172. He resided in a tent where he received the submission of the Irish Kings. He also issued a charter which is the earliest document in the Dublin City Archives. This gave to the men of Bristol the right to live in the city of Dublin ‘ad inhabitanda’. The tiny parchment measures 121 mm x 165 mm and a fragment of the seal remains in green wax. The charter is written right through, leaving no room for additions – a measure taken to prevent fraud. The 1175 Treaty of Windsor acknowledged Henry as overlord of the conquered territory and Ruaidrí as overlord of the remainder of Ireland, with Ruaidrí also swearing fealty to Henry. The Treaty soon collapsed: Norman lords continued to invade Irish kingdoms and the Irish continued to attack the Normans. Despite the charter in favour of Bristol the bulk of its Irish trade was with Waterford, Cork, Youghal, Dungarvan, Wexford, Kinsale and New Ross. The Dublin–England trade was predominantly with Chester.

Consolidation

There were most likely secular canons at Downpatrick, the traditional burial place of St. Patrick, prior to c.1183 when John de Courcy (the Norman conqueror of Ulster) threw them out and brought in Benedictine monks from Chester: he stipulated, however, that the new cathedral priory should be free of any dependency on Chester. It is claimed that de Courcy miraculously found the bones of St Patrick, St Brigid and St Colmcille at Downpatrick. In the presence of the Papal Legate, Vivian, the relics were reburied inside the cathedral on 9 June 1196. This story of their discovery is thought to have been crafted by de Courcy for political reasons. Lewis' Topographical Dictionary provides the following additional information:

- "De Courcy having espoused the claims of Prince Arthur, Duke of Brittany, assumed, in common with other English barons who had obtained extensive settlements in Ireland, an independent state, and renounced his allegiance to King John, who summoned him to appear and do homage. His mandate being treated with contempt, the provoked monarch, in 1203, invested De Lacy and his brother Walter with a commission to enter Ulster and reduce the revolted baron. De Lacy advanced with his troops to Down, where an engagement took place in which he was signally defeated and obliged to retreat with considerable loss of men. De Courcy, however, was ultimately obliged to acknowledge his submission and consent to do homage. A romantic description of the issue of this contest is related by several writers, according to whom De Courcy, after the termination of the battle, challenged De Lacy to single combat, which the latter declined on the plea that his commission, as the King's representative, forbade him to enter the lists against a rebellious subject, and subsequently proclaimed a reward for De Courcy's apprehension, which proving ineffectual, he then prevailed upon his servants by bribes and promises to betray their master. This act of perfidy was carried into execution whilst De Courcy was performing his devotions unarmed in the burial-ground of the cathedral: the assailants rushed upon him and slew some of his retinue; De Courcy seized a large wooden cross, with which, being a man of great prowess, he killed thirteen of them, but was overpowered by the rest and bound and led captive to De Lacy, who delivered him a prisoner to the king. In 1205, Hugh de Lacy was made Earl of Ulster, and for a while fixed his residence at the castle erected here by De Courcy."

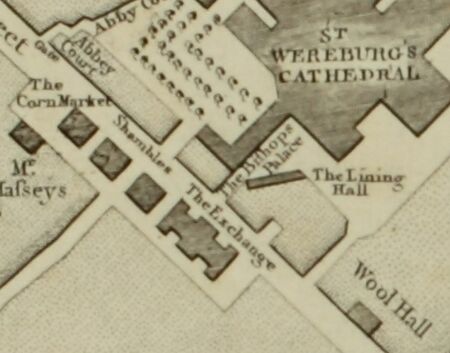

Curiously the cult of St Werburgh was sufficiently strong in Chester for churches to be founded in her name elsewhere, not least in Dublin where the church of St Werburgh’s was established close to Dublin Castle around 1178 (Jonathan Swift was baptised there in 1667). The street name has been Gaelicised to "Sráid Bharbra": which actually sounds like "Werburgh", the Irish alphabet does not include 'w' and the 'gh' combination is not used. The Church of Ireland Primate – James Ussher was appointed to this church in 1607, and Edward Wetenhall, afterwards Bishop of Kilmore, author of the well-known Greek and Latin Grammars, was curate here. Swift's friend, Dr. Patrick Delany (1685–1768), was rector of the parish in 1730. Ussher would himself halt at Chester to visit Christopher Goodman (1520–1603), a sturdy Nonconformist, mistakingly reputed by some, on account of his book against Mary, Queen of Scots ("How superior Powers ought to be obeyed of their subjects, and wherein they may lawfully be by God's word disobeyed and resisted"), to have been the author of "The Monstrous Regiment of Women" and who was then on his death-bed. In his time he had refused to subscribe to the prayer-book and articles. For his recusancy Archbishop Parker had Goodman "beaten with three rods," and forbade him to preach. Goodman was involved in the banning of the Chester Mystery Plays.

King John

Had all gone according to plan, King John would not be known as one of the worst kings ever to sit on the English throne. Less than a decade into the English invasion of Ireland, in 1177, King Henry II looked to reorganise his newest acquisition. The leader of that invasion, Richard fitz Gilbert (Strongbow), had died the previous year and the conquest threatened to falter. A new leader was needed, and Henry used the opportunity to provide for his youngest son, John ‘Lackland’. At the Council of Oxford (1177), Henry dismissed William FitzAldelm as the Lord of Ireland and declared that the ten-year-old boy should be crowned king of Ireland. Part of the evidence for this is a short-lived issue of half-pennies struck in Dublin in 1179: this first issue featured a profile portrait of John with the legend IOHANNES (or a contracted form) on the obverse.

This decision was perhaps more about Angevin court politics than it was about the situation in Ireland, but it nevertheless began an association between John and Ireland that would span almost four decades. John had at the time three surviving older brothers, one of whom, Henry, had already been crowned junior king of England in 1170 to secure his succession there. The approval of Pope Alexander III was sought to have John crowned King of Ireland. Disagreements with first Alexander III and then his successor Pope Lucius III caused this to be delayed and instead John became only "Lord of Ireland".

The Annales Cestriencis confuses matters slightly as it does not mention the Council of Oxford in 1177, and states that John was first given the Lordship of Ireland in 1184, when he sent Philip of Worcester (c.1160–c.1218) to Ireland with a force of 40 knights:

- "Also Henry [II.], k-ing of England, first gave to his son John the lordship of Ireland. Which John sent Philip of Worcester with a great retinue into Ireland for the purpose of undertaking the defence of Ireland."

Gerald of Wales was chosen to accompany John, in 1185, on his first expedition to Ireland (April-December 1185). This was the catalyst for Gerald's literary career; his work Topographia Hibernica (first circulated in manuscript in 1188, and revised at least four times) is an account of his journey to Ireland; Gerald always referred to it as his Topography, though "history" is the more accurate term. He followed it up, shortly afterwards, with an account of Henry's conquest of Ireland, the Expugnatio Hibernica. Both works were revised and added to several times before his death, and display a notable degree of Latin learning, as well as a great deal of prejudice against foreign people. Gerald was proud to be related to some of the Norman invaders of Ireland, such as his maternal uncle Robert FitzStephen and Raymond FitzGerald, and his influential account, which portrays the Irish as barbaric savages, gives important insight into Cambro-Norman views of Ireland and the history of the invasion.

The Annals of Chester give the following account for the year 1185:

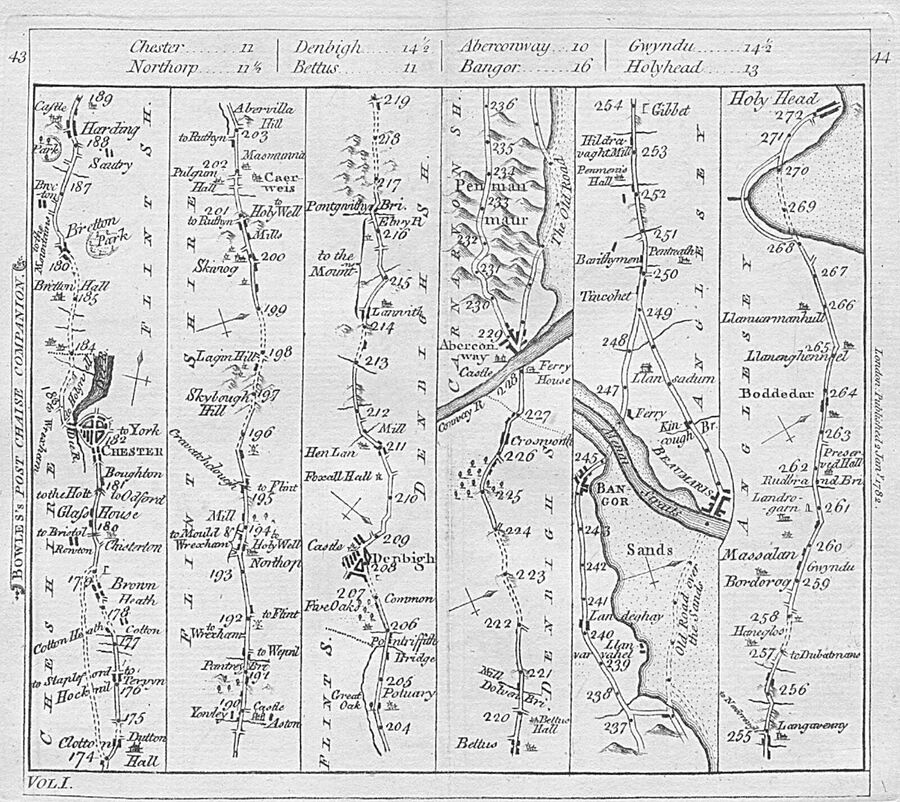

- mclxxxv Johannes sine terra filius Regis Henrici II. cum multa manu armatorum et navium multitudine apud Penbroch Wallie mare ingrediens Ebdomada pascali Hiberniam Rex coronandus petiit. Ceteri vero Anglie cc justicie et primores cum ejus (?) sociis apud Cestria iter navale arripiunt. Eodem anno interfectus Hugo de Lacy a quodam Hiberniense in Hibernia. Quo audito Henricus rex preparuit Johannem filium suum iterum mittere in Hibernia. Qui Johannes veniens Cestriam dum ventum ibi expectat, nuntiatur patri suo mors Galfridi fratris sui comitis de Britania. Qua audita Henricus rex revocare fecit Johannem filium suum et misit in Hiberniam Phillippum de Wigornia cum aliis quam paucis. (John Lackland, son of king Henry II., with a great band of armed men, and a multitude of ships, arrived by sea at Pembroke in Wales. On the Sunday after Easter he started for Ireland in order to be crowned king there. But two hundred other justices and nobles of England, with his [their ?] companions, commence their sea voyage to Ireland at Chester. The same year Hugh de Lacy was killed in Ireland by a certain Irishman. When king Henry heard of it, he prepared to send his son John again into Ireland. But when John had come to Chester, and was waiting for a [favourable] wind, the death of his brother Geoffrey, count of Brittany, is announced to his father; when Henry heard of this, he caused his son John to be recalled, and sent Philip of Worcester with a very few others to Ireland.)

John was also accompanied to Ireland by Gilbert Pipard, the former guardian of Ranulf de Blondeville during the minority of the latter. From the moment he set foot in Ireland in 1185, the seventeen-year-old John displayed a self-assured arrogance towards his intended subjects. Even Gerald understood the need for discretion in face-to-face dealings, and chastised John for his treatment of the previously loyal Irish kings who came to render him service. Gerald claims that John and his companions mocked the Irishmen’s "outlandish" dress and pulled their unfashionably long beards. True or not, the story is at least in keeping with the disregard for property rights, loyalty and diplomacy that John showed when dealing with the Irish. The would-be king alienated many of the island’s resident élites (Irish and English).

On his return John complained bitterly to Henry II that Hugh de Lacy the governor of Ireland, would not permit the Irish to pay tribute. In 1186 Hugh de Lacy was killed by Gilla-Gan-Mathiar O'Maidhaigh, while he was supervising the construction of a Motte castle at Durrow. Plans were made to send John over to Ireland to take possession of his lands as the new Pope Urban III (1185-87) apparently approved. However, the death of his brother, Geoffrey II, Duke of Brittany, in France cancelled these plans while John was waiting at Chester and John did not return to Ireland until his second expedition in 1210. A golden crown set with peacock feathers reportedly arrived from Rome the following year — John had his belated papal approval

Norman Decline

In 1201 King John gave notification of his confirmation to the men of Chester of liberties in Ireland, granted by King Henry II and confirmed by the present King whilst count of Mortain (in 1192). He followed this up by a Charter of King to the Citizens of Chester in which he styles himself "King of England and Lord of Ireland" and:

- "requests all Justices, Constables, Bailiffs and faithful people in the whole of Ireland to grant the citizens of Chester liberty to trade in Ireland as in the time of our Father King Henry II"

Furthermore John ordered that should the Justicar of Ireland take any of the goods he should pay a resonable market price for them. Undoubtedly, the traders of Chester paid for this royal protection. The intermediaries between the burgesses and the kings would have been the Earls of Chester. Henry II, in 1171 had granted permission to the Burgesses (citizens) of Chester to buy and sell at Dublin:

- "having and observing the same customs which they observed in the time of King Henry my grandfather."

Thus, there had been some form of official sanction of trade between Chester and Dublin in place since the reigh of Henry I (1100-35). Records of several charters mention trade between Chester and Durham, and some of these (such as that of 1160), if not all, may confuse the latin "Diuelina" (Dublin) with "Dunelina" (Durham). There are also suggestions that Ranulf de Blondeville travelled to Ireland but these are probably legendary and no historical basis can be found. Economic exploitation generated population movement on a spectacular scale. The names of more than a thousand migrants bearing names suggesting origin in England, Wales, and France are recorded as citizens of Dublin c. 1200.

The Norman settlers in Ireland later became known as Norman Irish or Hiberno-Normans. They originated mainly among Cambro-Norman families in Wales and Anglo-Normans from England. During the High Middle Ages and Late Middle Ages the Hiberno-Normans constituted a feudal aristocracy and merchant oligarchy, known as the Lordship of Ireland. In Ireland, the Normans were also closely associated with the Gregorian Reform of the Catholic Church in Ireland. The military power of the crown in Ireland was greatly weakened by the Hundred Years War (1337–1453).

The Black Death arrived in Ireland in 1348. Because most of the English and Norman inhabitants of Ireland lived in towns and villages, the plague hit them far harder than it did the native Irish, who lived in more dispersed rural settlements. After it had passed, Gaelic Irish language and customs came to dominate the country again. The English-controlled territory shrank to a fortified area around Dublin (the Pale), whose rulers had little real authority outside (beyond the Pale). By the end of the 15th century, central English authority in Ireland had all but disappeared. England's attentions were further diverted by the Wars of the Roses (1455–85).

The Battle of Piltown took place near Piltown, County Kilkenny in 1462 as part of the Wars of the Roses. It was fought between the supporters of the two leading Irish magnates Thomas FitzGerald, 7th Earl of Desmond, head of the government in Dublin and a committed Yorkist, and John Butler, 6th Earl of Ormond who backed the Lancastrian cause. It ended in decisive victory for Desmond and his Yorkists, with Ormond's army suffering more than a thousand casualties. This effectively ended Lancastrian hopes in Ireland and bolstered FitzGerald control for a further half-century. The Ormonds departed into exile, although they were later pardoned by Edward IV. It was the only major battle to be fought in the Lordship of Ireland during the Wars of the Roses. It is also part of the long-running feud between the FitzGerald dynasty and the Butler dynasty. The early 15th century had seen some trade through Chester of bowyers from Yorkshire, at least one of whom became a freeman of Chester: later they were superseded by merchants from Halifax, Pontefract, and Bradford, exporting cloth from the West Riding and returning with Irish furs. Until the later 15th century the English city with which Chester was most strongly linked was Coventry. Its merchants regularly passed through Chester en route for Ireland, taking with them cloth, dyestuffs, and occasionally the sweet wines of the Mediterranean, and perhaps returning with hides. By the later 15th century Irishmen were prominent in Chester's guild merchant; at least 6 of the 17 men entering the guild in 1474 came from Dublin and a seventh from Drogheda. Others opted for citizenship. Robert Nottervill, mayor of Chester in 1478-9, had apparently twice served as mayor of Drogheda. Not all Irish immigrants were of high status, and in the early 15th century they included male and female labourers, and women who turned to keeping brothels in Chester. Some of the brothels were in Watergate Street. Agnes Irish and Emma Trim were fined for keeping brothels there in 1463, as was Elizabeth Ireland in 1476. Thirty years later Katherine Irishwoman of Greyfriars was accused of brothel keeping.

By 1500 Irish and coastal trade accounted for over 75 per cent of all inward sailings to Chester, rising to 95 per cent in 1548-9. There was an active re-export trade between Chester and Ireland in both directions, suggesting that Irish merchants picked up what they could as return cargoes, and were perhaps more concerned with selling in Chester than with buying. Some traditional commodities had disappeared from Anglo-Irish trade. Cheshire salt was not exported via Chester after 1450 and had been replaced by salt from the bay of Bourgneuf carried in Breton and Gascon ships. Irish corn imports faded after a ban in 1472. Most cargoes were a mixture of cloth, fish, hides and skins, linen (both cloth and yarn), wool (fells, flocks, and yarn), honey, tallow, wax, and occasional reexports such as silk. The trade was concentrated in the Pale, and not with wealthier Waterford, Cork, and Kinsale.

Since the Normans had arrived in Ireland the power and influence of the English crown in Ireland had fluctuated but at no time could it have been said to have exerted total control. Such a situation was however to witness a significant change with the succession of the Tudor dynasty to the throne of England. This new approach was to be based on the need to enlarge the power and influence of the crown throughout Ireland by means of a powerful and centrally-controlled administration. Although at times various methods were to be adopted to achieve such an objective there remained throughout a determination that in the future Ireland would be subject to strong government under the crown. The Tudor reconquest of Ireland took place during the 16th century. Irish salmon continued to find a market in Chester and over 5 tons and 260 butts was imported in 1543-4.

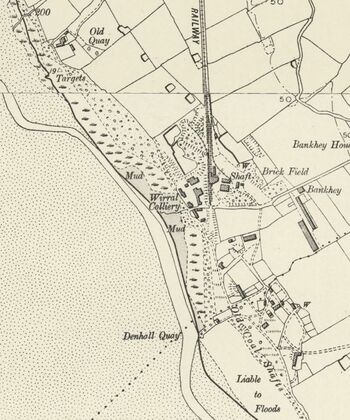

Tudor and Stuart Trade

Shotwick, being one of the nearest anchorages to Chester became a busy little port. It has been suggested that Henry II left there for Ireland, but there is no primary source for this and he seems to have sailed from Milton Haven. During the reign of Henry VI (1422-71) a quay may have built there and the "creek" was in use as a landing, although possibly only for smuggling. Silting eventually reduced the depth of the channel at Shotwick and shipping moved along the coast to the deeper waters of Burton Point and Denhall. Burton Church is dedicated to St. Nicholas, the patron saint of mariners and at Denhall in Ness was the ancient Hospital of St. Andrew. The hospital, for the use of poor travellers from Ireland and other poor or shipwrecked men is first mentioned c.1234.

As long as the Dee remained navigable, Ireland was Chester's chief overseas trading partner, and as such the main source of Chester merchants' prosperity in the later Middle Ages and the 16th century. Although the early 16th century overseas trade at Chester with Ireland, Spain, Portugal, and Brittany expanded, only merchants with a sizeable turnover could carry the heavy costs which arose from carriage from anchorages down the River Dee estuary and from high customs duties. The share of the port's trade controlled by Cestrians fluctuated. Dubliners, probably with some Norman or Anglo-Norman ancestry at times dominated the Irish Sea trade, and there was strong competition for the rest of the overseas trade from English, Welsh, and Continental merchants. The involvement of the city's own leading merchants appears to have ceased between the 1460s and the 1490s. Thereafter, however, their share increased until in the 1510s they were dominant. Such merchants, generally aldermen or common councillors, were engaged mainly in the Spanish trade but also maintained an interest in the Irish and coastal trade. In 1538-42, during Chester's trading zenith, 40-45 per cent of traders were Chester freemen. Most were probably only occasionally involved, and between 1500 and 1550 there were forty or so significant Chester merchants who shipped through the port. Their trade was predominantly in importing iron and wine and exporting hides and cloth, but few were specialists.

In the mid 16th century, while Chester exported more cloth to the Continent than Liverpool did, Liverpool had overtaken Chester in the Anglo-Irish trade. Liverpool's success was due in part to its location closer to the textile centres in Lancashire and in part to Chester's reluctance to adapt to market forces. No exemptions from Chester's local customs were allowed, except in a reciprocal agreement with Wexford. While Chester freemen made a single payment of 4d. a vessel, outsiders had to pay on every major item imported and exported. Dubliners claimed the lower dues payable at Liverpool as a major attraction in 1533, and in 1550 the mayor of Dublin complained to his counterpart in Chester that increases in customs dues encouraged merchants to sail elsewhere. However in 1569, even Liverpool was still ‘a creek port within the Port of Chester’ in legal terms, with a fleet of only 12 ships. Over half a century later, during the reign of Charles I (1625-49) £100 ship money was demanded from Chester, and willingly paid, but only £15 from Liverpool.

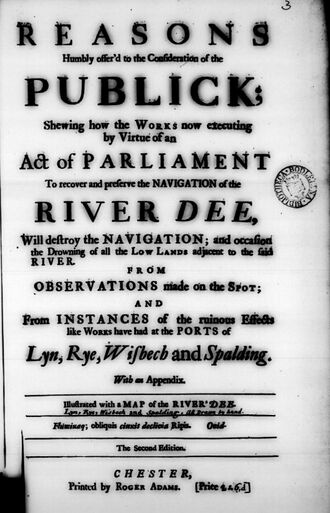

In 1541 the Chester corporation adopted a plan to build a new harbour some 10 miles down the Dee estuary at Lightfoot's Pool in Little Neston, perched on a sandstone outcrop jutting out to sea, and Henry VIII ordered 200 trees to be delivered to the mayor for that purpose. The name "Neston" is of Viking origin, deriving from the Old Norse Nes-tún, meaning 'farmstead at/near the promontory'. In 1548, in response to a petition from the city for aid with the work, the orders were repeated and augmented by a grant of £40 for seven years. Despite a further appeal for a royal grant in 1551, the city was forced to raise funds locally; between 1555 and 1560 voluntary rates and special assessments were imposed on the guilds, parishes, and citizens, and special payments were exacted from members of the corporation. Work was evidently well under way by 1565, when a salaried overseer was appointed. In 1566, however, the "great pier of stone" which formed the main feature of the haven was largely overthrown in a gale. To repair the damage a further special assessment was made in 1568 on the citizens and the guilds of Chester, and councilmen were ordered to oversee the work at their own cost. The New Haven, otherwise known as Neston Quay or New Quay, eventually comprised an anchorage protected by a stone pier. The project, which was probably never completed, remained a constant burden on Chester's finances throughout the later 16th century, despite appeals to the Crown for grants out of customs revenue in 1576 and 1589. Its repair was aided by the Ironmongers' company in 1571, and was the subject of further orders by the Assembly in 1576, 1587, and 1598. The city's last recorded expenditure upon it was in 1604. By 1743 the New Quay had become known as the "Old Quay". When the River Dee was canalized with the opening of the New Cut in 1737, another New Quay (which later became Connah’s Quay) was formed at its outer end. The Old Quay at Neston was abandoned after 1704 and in 1799 its stone was bought by Sir Thomas Mostyn, and some of the stone blocks were reputedly used to build the sea wall at Parkgate.

Chester's links with Ireland at the time are preserved in the story of the "Blue Posts", which was an inn located in Bridge Street. Hughes (and many others) tell the following story:

- "A little way down this Row was an ancient tavern called the Blue Posts supposed to be the identical house now occupied by Mr Brittain woollen draper. In this house a curious incident is stated to have occurred in 1558 which tradition has handed down to us in the following terms. It appears that Dr Henry Cole, Dean of St Paul's, was charged by Queen Mary with a commission to the council of Ireland which had for its object the persecution of the Irish protestants. The doctor stopped one night here on his way to Dublin and put up at the Blue Posts then kept by a Mrs Mottershead. In this house he was visited by the mayor to whom in the course of conversation he related his errand in confirmation of which he took from his cloak bag a leather box exclaiming in a tone of exultation: "Here is what will lash the heretics of Ireland!". This announcement was caught by the landlady who had a brother in Dublin and while the commissioner was escorting his worship down stairs, the good woman prompted by an affectionate regard for the safety of her brother opened the box took out the commission and placed in lieu thereof a pack of cards with the knave of clubs uppermost. This the doctor carefully packed up without suspecting the transformation nor was the deception discovered till his arrival in the presence of the lord deputy and privy council at the castle of Dublin. The surprise of the whole assembly on opening the supposed commission may be more easily imagined than described. The doctor in short was immediately sent back for a more satisfactory authority but before he could return to Ireland Queen Mary had breathed her last. It should be added that the ingenuity and affectionate zeal of the landlady were rewarded by Elizabeth with a pension of £40 a year."

Mary died 17 November 1558, which allows the story to be roughly dated. Another writer in "The Old Inns of Old England" states that:

- "The former "Blue Posts" .. was long since refronted in respectable, but dull, red brick, and is now, or was recently, a boot-shop. But although no hint of its former self is given to the passer-by, those who venture to make a request, are shown a fine upstairs room, with an elaborately pargeted ceiling, still known as the "Card Room".

There does seem to have been some special relevance assigned to the Jack of Clubs, in the reign of Queen Elizabeth I there were reports of the Jack of Clubs being left hanging in desecrated churches. There is also a minor mystery in that the card is first mentioned in the French literature only from 1557 and not mentioned in English works on cards until 1709 when it was described as being "much used in gambling games" and was frequently a "wild card". The most likely location of the "Blue Posts" is given in July 1863, when the Cheshire Observer referred to "The Rising Sun", stating that it was formerly the venerable Blue Posts Inn and reciting the legend. According to some accounts the Rising Sun was located at 8 Bridge Street Row, although there is an early map of Chester which has it placed on the opposite side of the street. While Henry Cole is a known historical character the veracity of his misadventure in Chester remains unclear.

Elizabeth

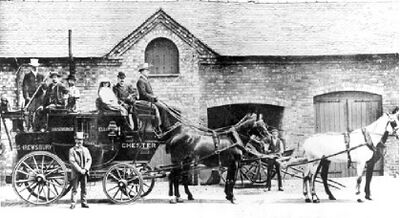

Chester's political importance to the English Crown from the 1590s into the early 18th century arose because it was the main staging post on the route between the two capital cities: about 185 miles from London by road (see: Road Transport) and 150 from Dublin by sea (see: Portpool). However, one of the main difficulties of the last years of the rule of Queen Elizabeth was the war in Ireland which broke out in 1579. The crisis point of the Elizabethan conquest of Ireland came when the English authorities tried to extend their authority over Ulster and Aodh Mór Ó Néill, the most powerful Irish lord in Ireland. Though initially appearing to support the crown, Ó Néill engaged in a proxy war in Fermanagh and northern Connacht, by sending troops to aid Aodh Mag Uidhir lord of Fermanagh. This distracted the crown with military campaigns in the west while Tyrone consolidated his power in Ulster. Ó Néill openly broke with the crown in February 1595 when his forces took and destroyed the Blackwater Fort on the Armagh-Tyrone border. Later named the Nine Years War, Ó Néill focused his action in Ulster and along its borders, until Spanish promises of aid in 1596 led him to spread the conflict to the rest of Ireland.

Chester was the main port used for sending English troops levied in other parts of the country, who passed through the city frequently and in growing numbers. The mayor and other officials were often fully occupied with receiving them and arranging quarters, food, and money. Ships were requisitioned and provisioned, and supplies of food, drink, stores, and ammunition were sent to Ireland. The repeated demands strained local markets, especially during the shortages of the later 1590s: prices rose, ships' masters demanded large payments, disaffected men deserted in droves and were rarely captured, weapons were often found to be defective, moneys were embezzled, profiteering was rife, and Chester earned a reputation as a "robber's cave". Disorderly conduct was frequent, especially when troops were delayed by bad weather or lack of ships. To contain it, in 1594 the mayor erected a gibbet at the High Cross.

With the Irish victory at the Battle of the Yellow Ford, the collapse of the Munster Plantation, followed by the dismal vice-royalty of Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, the power of the Crown in Ireland came close to collapse. In October 1601 Spanish forces landed in Ireland. During the two years from early 1600 many reinforcements passed through Chester, the mayor received a stream of orders from the privy council, and there were further problems of supply and unruly behaviour.

King James

After the Spanish War and with the ascension of James I eight merchants controlled over fifty percent of the overall trade at Chester. The eight included the surviving Aldersleys and the Gamulls. In the early seventeenth century Chester’s population within the city walls numbered around 5,000. The local economy revolved around the leather industry, whose craftsmen comprised approximately 23 per cent of the freemen (see: Tanning). Most trade was with Ireland, particularly Dublin, which supplied considerable quantities of hides. Concessions to merchants who were not freemen were rare, but in 1607 non-free importers of Irish yarn were permitted to sell it without restriction in an attempt to divert them from Liverpool. Chester's coastal trade continued, but Ireland remained the city's main commercial outlet. Coal exports and livestock imports had little direct effect on the city: both were shipped at anchorages in the estuary, mainly by Irish merchants in vessels not owned locally.

Chester's cloth trade was at a low ebb in the first decade or so of the 17th century, but it improved during the 1620s and certainly expanded considerably in the 1630s, particularly from about 1632. The modest nature of the trade and its connection with Ireland (which seems to have increased its cloth imports in these years) rather than with France and southern Europe, undoubtedly enabled Chester to avoid the worst disasters of the middle and later 1620s which particularly affected most of the other provincial ports. The fluctuations of Chester's cloth trade in such years as 1621, 1625 and 1628-9 do not bear comparison with the extreme slump which other provincial ports suffered. Some of these had not recovered by the outbreak of the Civil War.

Civil War

War in Ireland began again with the Irish Rebellion of 1641, when Irish Catholics rebelled against English Protestant rule. When news of the insurrection reached King Charles I, he and the English Parliament promised to send troops. It led to the 1641–1652 Irish Confederate Wars, part of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, with up to 20% of the Irish population becoming casualties. The Confederation eventually sided with the Royalists in return for the promise of self-government and full rights for Catholics after the war. On 14 June 1645, Charles's main army was decisively beaten at the Battle of Naseby by the New Model Army under Sir Thomas Fairfax. The King then withdrew to Hereford, hoping for more reinforcements from Wales and Ireland.

During the early part of the Civil War Chester was in Royalist hands and was beseiged to an increasing extent. It is often said that Charles wished to keep Chester open as a port during the Civil War so that he could land troops from Ireland. The Confederates, in the context of the English Civil War, were divided over whether to send military help. Ultimately, they never sent troops to England save for one instance, but did send an expedition to help the Scottish Royalists, sparking the Scottish Civil War. Whether landing Royalist troops from Ireland at Chester ever made any military sense in the larger-scale conduct of the war is doubtful.

The Nantwich Campaign

The exception was the Irish Royalist campaign of November 1643 - January 1644.