St Johns

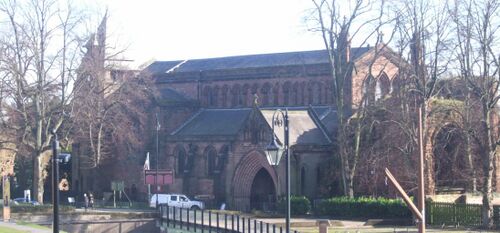

Often said to be "Chester's Hidden Gem"; It's not really that hidden, being right next to the Amphitheatre and plainly visible from the banks of the River Dee, you can't really miss it. The church has ruins at both ends, of which more below, and while the outside has been "restored" the inside retains many original Norman and early Gothic features - once inside it is like being in a different building, if not being in a different age. Just down the Hill, between the church and the river is the mysterious Hermitage, supposedly the hiding place of Harold II after the Battle of Senlac Hill, and rumoured (although there is again no proof) to be connected to the church by a secret passage - recent geophysical studies showed no traces of such a passage (although the data for the relevant location was described as "anomalous"!).

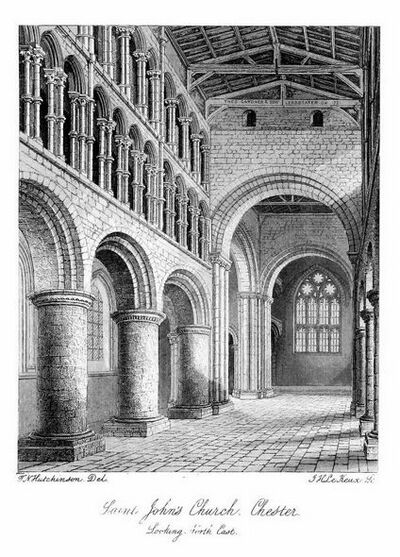

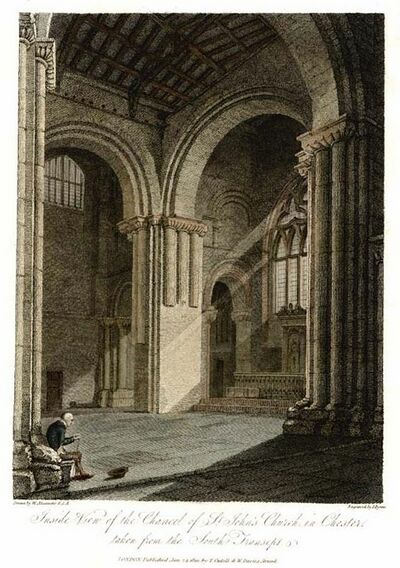

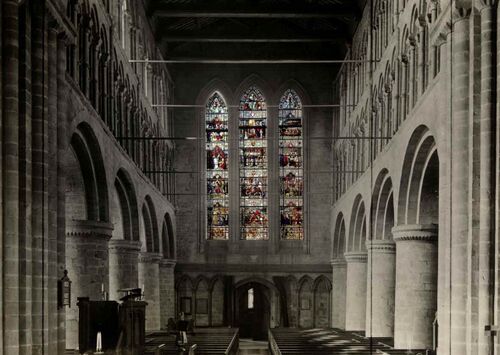

The interior of the building is a classic (and perhaps definitive) example of the transition from "Romanesque" architecture, a style known by its massive quality, thick walls, round arches, sturdy piers, groin vaults, large towers and decorative arcading, to early English Gothic (with returning crusader influence). The overall appearance is one of simplicity when compared with the "full-on Gothic" buildings that were to follow. A very detailed description of the physical structure of the church has been written by Ron Baxter: it seems poinless to reprise all that detail here. So we shall concentrate on on the more "interesting" features of its history for the general visitor.

St John's history (see below) is notable for a chronic shortage of building and repair funds and for parts of the structure falling down (it steadfastly carries this tradition on today). It is also steeped in ecclesiastical history and known for a notable relic as well as being one of the most often painted churches in England. On any visit to Chester it is not to be missed (and you can get a cup of tea for 80p - cheapest in town as of 2015).

Foundation

The site of St Johns is possibly that of a Roman Christian Church or Shrine, although there is no hard evidence for this. One theory that has been proposed is that early Christians built shrines near to places like the Amphitheatre where many of their predecessors may have been put to death. It's also worth noting that some of symbolism associated with the church, that of the White Hart, has pagan connections (although the White Hart later became a Christian symbol).

King Æthelred and the White Hart

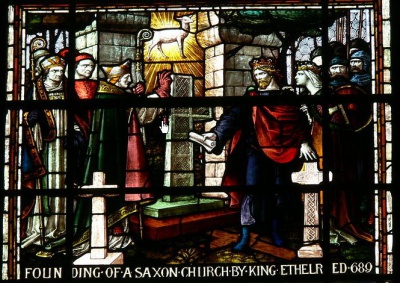

Tradition ascribes the foundation of St. John's to Æthelred, king of Mercia (674–704), in 689. The direct authority for this statement quoted by John Leland is the Itinerary of Giraldus Cambrensisc (Gerald of Wales). However no such information is found in the surviving texts of the Itinerary (it was written in 1191). Two authorities of a subsequent date quote the early date in such a mannner as to imply their acceptance of it, and the source as being Giraldus: the MS Chronicle of St Werburgh and by Henry Bradshaw a native of Chester and monk of St Werburgh's Abbey (later the Cathedral}. In his "Life of St Werburgh" (1513), Bradshaw writes:

- "The year of grace six hundred fourescore and nyen As sheweth myne auctour a Bryton Giraldus Kynge Ethelred myndynge moost the blysse of Heven Edyfyed a Collage Churche notable and famous In the suburbs of Chester pleasaunt and beauteous In the honor of God and the Baptyst Saynt Johan With helpe of bysshop Wulfrice and good exortacion"

This rhyming legend has been copied and is still extant on a tablet which is suspended at the south west angle of the nave near the font. Although the copyist misread the word "exortacion" and spelled it "Excillion". In "The Medieval Architecture of Chester", John Henry Parker, writes that this was "a mistake into which others have subsequently fallen under the idea that the abbreviated word was the name of a person".

A problen with this source is that Bradshaw (d.1513) gives his source as "Giraldus" (Gerald of Wales, 1146-1223), whereas the surviving Itinerarium Cambriae (1191) of Gerald's travels does not mention the founding of St John's at all. Leyland also refers to Gerald as his source, but whether this is a "cumulative error" or parts of Gerald's works have been lost is impossible to say. Hemingway sheds a little more light on the matter as he refers to the source of the quote as the Polychronicon of Higden (c. 1280 - c. 1363). However, while the Polychronicon contains one of the earliest sources for the legend surrounding Werburgh and her arrival in Chester, the wording is quite different. The relevant passages can be found in book V (Harl Mss 2261):

- "King Ethelred, uncle to Werburgh made her govenor in diverse places as at Threekingsham, Weedon and Hanbury, [she] dying at at first place and [was] buried at the third, as she commanded in her life, where she lay incorrupte as by three hundred years unto the coming of the Danes. The Danes tarrying in winter at Repton, [with] Burgered king of the Mercians chased away, the citizens of Hanbury, dreading them, went to Chester with the body of that blessed virgin, which reduced at that time to powder. In which city from the time of king Athelstan unto the coming of the Normans into England, secular cannons getting diverse posessions served in that church to the lawe of that virgin, and after that monks."

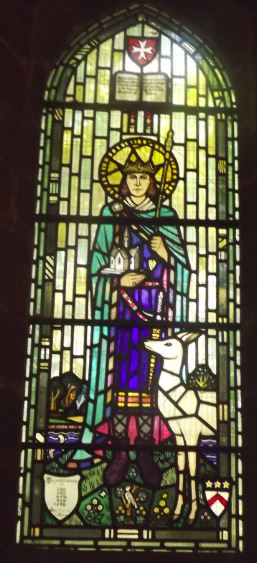

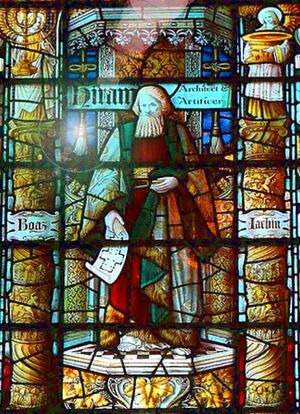

Equally without support is the legend that Æthelred selected the site after a dream in which he was told to build a church where he saw a white hart. A stained glass window in the porch of the church shows the king with a white hart (there is a similar legend about David I of Scotland and "Holyrood Abbey"). It seems that Æthelred was a devout king, "more famed for his pious disposition than his skill in war". In 704, Æthelred abdicated to become a monk and abbot at Bardney, leaving the kingship to his nephew Coenred. There is much more on this period in the article Dark Ages.

The "Annals of Chester" give much the same facts about the origin:

- "In the year of our lord six hundred and eighty-nine Ethelred, king of the Mercians, the uncle of St Werburgh, with the assistance of Wilfric, bishop of Chester, as Giraldus [Cambrensis] relates, founded a collegiate church in the suburbs of Chester in honour of S. John the Baptist (Annals of Chester)"

Curiously, churches associates with white harts occur all along the River Dee. They are also generally associated with holy wells or springs. Examples include: Llandderfel and Llangar. Just downhill from St John's was Jacobs Well - now relocated to Grosvenor Park.

The story of the hind/stag also turns up in the Journal of the Archaeological Society (Vol 2):

- "Mr. J. H. Parker, F.S.A., read a paper “On St. John’s Church, Chester.” It appeared at, length in the Gentleman's Magjazine, 1858, pp. 273— 281. We will merely state here that Mr. Parker was of opinion that the present north-west tower, half detached as it stands, was completed in the time of Henry VII. or Henry VIII. In the west face of the tower there is a figure of St. Giles, abbot, in a niche of well-designed work, with his usual emblem, a stag, in his hand, to which the tradition of the white hind has been for centuries locally applied."

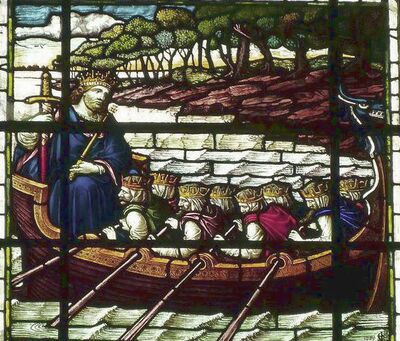

The Stained Glass window at St Johns is the work of Trena Cox (1895-1980) and dates from 1969.

The original structure would not have been a stone structure as seen today. Writing some years later, William of Malmesbury describes contemporary churches (at Rochester for example) as being "of wattle work covered with a casing of boards". As for the cannons/monks, they would scarcely at that early date have been under any regular rule except such as they had framed for themselves. There is also no evidence that the original Church was on the same site as the present building, although it seems likely that it was.

Who was Wulfrice?

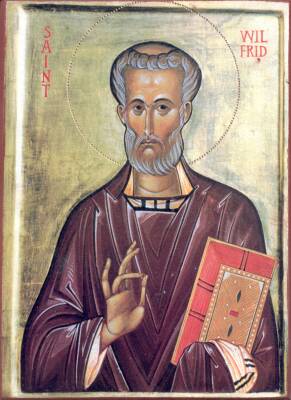

The "Wulfrice" (Wilfid) mentioned by Bradshaw and in the Annals of Chester appears to be an exiled Bishop from Northumbria. Æthelred had also made Wilfrid bishop of the Middle Angles, and supported him at the council of Austerfield in about 702, when Wilfrid argued his case for restoration to the see of York before an assembly of bishops led by Archbishop Berhtwald of Canterbury. Æthelred's support for Wilfrid embroiled him in dispute with both Canterbury and Northumbria, and it is not clear what his motive was, though it may be relevant that some of Wilfrid's monasteries were in Mercian territory. Wilfrid was not known for his diplomacy and commentators have said that Wilfrid "came into conflict with almost every prominent secular and ecclesiastical figure of the age". Hindley, an historian of the Anglo-Saxons, states that "Wilfrid would not win his sainthood through the Christian virtue of humility". Wilfrid was known as an advocate of Benedictine monasticism, regarding it as a tool in his efforts to "root out the poisonous weeds planted by the Scots". By 'Scots' he probably meant the Irish Celts, so his involvement in the establishment of St John's may well have been part of an attempt to wipe out the last of the influence of the "Celtic" church. In St John's, the head pieces from several early "Celtic" stone crosses can be seen, they are described in more detail on the Megalithic Portal. The Grosvenor Museum has another decorated cross head on display, which originally came from a "Celtic" monastic site on Hilbre Island. Exactly how the early Celtic Church and Wifrid might have come into conflict at Chester is unknown, however it is worth noting that there are two possible contenders for "holy wells" quite near St John's: Billy Hobby's Well (in Grosvenor Park) and Jacobs Well.

In part, it seems, Wilfid was a bishop with a see at Chester, at least according to the Polychronicon:

- "þerfore he appelede to þe court of Rome and defendede so his cause tofore þe pope Iohn þat he hadde lettres of þe pope to þe kynges of Engelond to his restitucioun þe redynge of þe synod þat was þoo rehersed was gret help to his cause þis Wilfridus hadde i be at þat synod in pope Agatho his tyme þe lettres were i-rad þat were i-sent for hym to kyng Alredus bote þe kyng wolde nou3t 3it fonge hym þerfore he tornede to þe kyng of Mercia and feng of hym þe bisshopriche of Legecestria þat is Chestre and helde it anon to Alfridus his deth"

This possibly includes a confusion of Chester with Leicester where Wilfrid is usually located as bishop from 692-705. Indeed, while the English translation of the Polychronicon mentions Chester the original Latin does not appear to do so.

sources

Alfred at Chester

Around 893, a fresh wave of Vikings crossed to England in 330 ships of two divisions and attacked. They landed and entrenched themselves, a larger body at Appledore, Kent, and a lesser, under Haesten, at Milton, also in Kent. If some accounts are to be believed the word "psychopath" is an understatement when used to descibe Haesten. The invaders brought their wives and children with them, indicating their intention of conquest and colonisation. King Alfred, in 893 or 894, took up a position from where he could observe both forces, but while he was in talks with Haesten, the Danes at Appledore broke out and struck north-westwards. They were overtaken by Alfred's eldest son, Edward the Elder, and defeated in an engagement on the outskirts of Farnham in Surrey (Edward later died leading an army against a Cambro-Mercian rebellion, on 17 July 924 at Farndon, south of Chester). Meanwhile, the force under Haesten set out to march up the Thames Valley, but they were met by a large force under three great ealdormen of Mercia, Wiltshire and Somerset. The Danes were driven off to the north-west, before finally being overtaken and blockaded. An attempt to break through the English lines failed and, after collecting reinforcements, the Danes made a forced march across England to occupy the ruined Roman fortress of Chester, arriving late in the year (see: Chester in 900). Just what the Danes are up to makes some sense when one realises that the Wirral had strong Viking connections after 902 and there may already have been some link ten years earlier.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells the story as:

- Þa hie on Eastseaxe comon to hiora geweorce. 7 to hiora scipum. þa gegaderade sio laf eft of Eastenglum, 7 of Norðhymbrum micelne here onforan winter 7 befæston hira wif, 7 hira scipu, 7 hira feoh on Eastenglum, 7 foron anstreces dæges 7 nihtes, þæt hie gedydon on anre westre ceastre on Wirhealum, seo is Legaceaster gehaten; Þa ne mehte seo fird hie na hindan offaran, ær hie wæron inne on þæm geweorce; Besæton þeah þæt geweorc utan sume twegen dagas, 7 genamon ceapes eall þæt þær buton wæs, 7 þa men ofslogon þe hie foran forridan mehton butan geweorce, 7 þæt corn eall forbærndon, 7 mid hira horsum fretton on ælcre efenehðe. 7 þæt wæs ymb twelf monað þæs þe hie ær hider ofer sæ comon.

- (As soon as they came into Essex to their fortress, and to their ships, then gathered the remnant again in East-Anglia and from the Northumbrians a great force before winter, and having committed their wives and their ships and their booty to the East-Angles, they marched on the stretch by day and night, till they arrived at a western city in Wirral that is called Chester. There the army could not overtake them ere they arrived within the ramparts: they besieged the ramparts though, without, some two days, took all the cattle that was thereabout, slew the men whom they could overtake outside the ramparts, and all the corn they either burned or consumed with their horses every evening. That was about a twelvemonth since they first came hither over sea.)

The story of Alfred at Chester is in many respects puzzling, for what were the Cestrians doing at the time? If it is assumed that the Vikings actually occupied the city, then they would surely have helped themselves to any provisions to be found. This would have meant starvation for the inhabitants of Chester. Even if the Vikings only occupied the "castle" (the Amphitheatre?) then the city (not to mention St John's Church) would have been an obvious target once Alfred left. One possible suggestion is that Chester was not actually inhabited at the time and that "westre ceastre" in the ASC should be read as a "waste" (i.e. abandoned) fortification. However, this is also strange, as within five years the city is described as being besieged by Vikings and shortly thereafter was extensively re-fortified.

Interestingly some "runic" inscriptions have been discovered at St Johns. These are believed to be in the so-called "Urnes" style which was the last phase of Scandinavian animal art during the second half of the 11th century and in the early 12th century. The Urnes style is named after the northern gate of the Urnes "stave" church in Norway, but most objects in the style are runestones in Uppland, Sweden. Perhaps this is re-use of the parts of a rune-inscribed cross or other monument in repair work. If the "castle" occupied by the Vikings (they must have occupied more than that as they were a sizable force) was indeed the Amphitheatre, then it's use as a defensive structure implies that quite a lot of it was still extant as a sizable structure at the time. Who knows whether some Viking graffiti on the Amphitheatre (it can be found far and wide - including in Hagia Sophia's marble parapets) was in stone that was later "robbed-out" and re-used at St John's.

Earl Æthelred and the Redcliffe cross factory

In 906 the Abbey of St John the Baptist was founded by a later Æthelred, Earl of Mercia (he was married to Æthelflæd). Mercian independence was not to last as in 907 Edward the Elder "regained Chester" after a battle. Some scraps of physical evidence remain: in 1860 a hoard of some 40 coins from the reign of Edward the Elder (899–924), found sixteen feet down just west of the present church, and perhaps buried in troubled times. Hughes believed that these were "foundation coins" and when they were originally displayed they were labled as such. However, in 924 Chester joined a Welsh revolt against English rule (William of Malmesbury records a Mercian revolt at Chester). The revolt was put down by Edward the Elder who died leading his army on 17 July 924 at Farndon - given that Edward had only "regained Chester" in 907, these do seem to have been troubled times. In 912 Chester was besieged by Ingamund, only to be repulsed by the "great army" which Æthelflæd assembled in the city (with the aid of boiling beer and beehives): as St Johns was outside the City Walls it is surprising it was not ransacked. One estimate places the hoard of coins as being hidden in c.920.

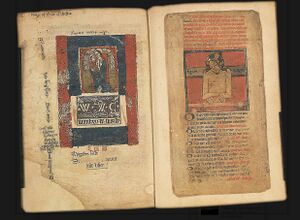

Fragments of several crosses, probably memorials dating from the 10th century, were recovered from St. John's churchyard and among the rubble of the collapsed tower in the late 19th century. The crosses, and others from Wirral and North Wales, were probably made at a workshop based on St. John's, using stone from the nearby quarry (now the bowling green down the hill). Indeed Bailey 2010 reports an unfinished cross at Chester. Such evidence suggests that St. John's was an important church in later Anglo-Saxon Chester. Links between the Chester crosses and those from Neston and Hilbre Island can be seen in that the circle diameter of the crosses are similar as are the interlace patterns. The crosses have been described as follows (by a past Bishop of Bristol):

- "It is more easy to describe these crosses negatively rather than positively. They are un-Anglican, un-Scottish, un-Irish, un-Scandinavian, they resemble most closely a head of one of the few great crosses made in Wales, known as Maen-Ach-Wynfan and the head of a cross at Diserth."

Concerning the cross heads, a printed sign in the Church says :

- "These stone crosses are reputedly from the workshop established in the quarry of St Johns by Irish - Norse traders who settled in Chester during the 10th Century. Similar crosses thought to have been from the same workshop have been found over a wide area as shown on the map."

..but a hand written note, very faded, also says:

- "Remains of Saxon crosses; these were unearthed from the eastern area of St Johns 1870 restoration. Their circular head design and squared shafts suggest Celtic origin, early Mercian AD750-900..."

A legend reports that in AD 946, the statue of the Virgin on the rood loft of the Church of St Deiniol, Hawarden, fell on the head of Lady Trawst, wife of the Governor of Hawarden Castle, and killed her. The statue was tried by jury and condemned to be thrown into the River Dee, eventually being washed up at the Roodee in Chester. In some versions of this tale the "statue" was merely a wooden cross (which would float better) which was then taken to St John's.

Edgar the Pacific - St John's has a coronation

Edgar the Pacific, (c. Aug 7, 943 – July 8, 975) was the great-grandson of Alfred the Great and was famously crowned both at Bath and at Chester (in 973) as the first king of all England. The religious rites used in his coronation (use of anointing etc.) were devised by Dunstan and have been in use ever since. King Edgar is said to have prayed in the minster ("monasterium") of St. John after being rowed along the River Dee. The rather fanciful illustrated tiles at the Bull and Stirrup in Chester show this event set against the backdrop of much later-built City Walls. St John's has a stained glass window showing the same event without the historical blunders, although Edgar is holding his sword rather than a tiller.

According to tradition, Edgar was rowed up the River Dee from Edgar's Field to his coronation. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records the meeting thus (versions again vary):

- A.D. 972. This year Edgar the etheling was consecrated king at Bath, on Pentecost's mass-day, on the fifth before the ides of May, the thirteenth year since he had obtained the kingdom; and he was then one less than thirty years of age. And soon after that, the king led all his ship-forces to Chester; and there came to meet him six kings, and they all plighted their troth to him, that they would be his fellow-workers by sea and by land.

Other versions, (including the window at St John's) have eight "kings" rowing the boat for Edgar. On the page about Edgar's Field there is a short discussion as to whether Edgar was actually rowed upstream from Chester or downstream from Farndon where there had probably been an important royal manor.

More evidence for early wooden construction of the Church can be found in a charter from this time when King Edgar on the exhortation of Dunstan "was excited by the insinuation of heavenly love" (as the words of his charter run) "to rebuild all the holy monasteries throughout his kingdom" he complains that "they were outwardly ruinous with mouldering shingles and worm eaten boards even to the rafters".

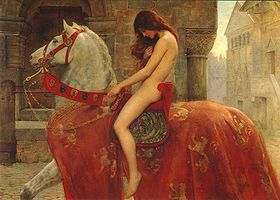

Leofric, Lady Godiva and Edward the Confessor

In 1057 nine years before the Conquest, Leofric earl of Mercia at the insistence of his wife Godiva repaired and enriched the monasteries of St Werburgh and St John in Chester with "precious ornaments". Abbot John Brompton writes:

- Assensu et consilio Godivae uxoris suae Monasteria Leonense juxta Herefordiam Wenelocense et in Cestria Sanctae Werburghae sanctique Joannis Wigorniae et Evesham reparavit similiter et ditavit.

And Leland:

- Leofricus rep coll S Joannis Cestriae

Little is known of the extent of Leofric's liberality or of the style and magnitude of his church restoration but Ormerod on the authority of the Werburgh MS and William of Malmesbury asserts that the church of St John's then collegiate church was repaired and its endowments and privileges considerably increased. Of the Saxon earl's reparations no trace now remains - the language of the historian seems to imply that they were composed of the same perishable materials as before. Simon of Durham says that:

- After the devastation of the north country in AD 867 by the Danes who reduced the churches and monasteries to ashes Christianity was almost extinct very few churches and those only built with hurdles and straw were rebuilt But no monasteries were re-founded until about 200 years after.

Much of the above is in part conjecture built on very shaky evidence, some of which may have been fabricated by later monastic writers either through a deliberate effort to establish a religious history for Chester or through simple misinterpretation of what even then could have been very scant sources. With the arival of the Normans there is much more solid evidence of St Johns being the seat of a bishop and having the status of a cathedral.

Rebuilt in Stone

The Norman Period

St John is mentioned as follows in the Domesday Book:

- "Ecclesia Sancti Johannis in civitate habet viii domos, quietas ab omne consuetudine: una ex his est matricularii ecclesia aliae sunt canonicorum"

Peter de Leia, bishop of Lichfield (consecrated in 1067) removed his episcopal see to Chester in 1075 during the Earldom of Hugh of Avranches. One theory as to why this was done is that the bishop saw some scope for extending his bishopric into North Wales, which was then being conquered by Hugh. Another reason is given by Henry de Knyghton - a council was held in London, under the presidency of archbishop Lanfranc, at which it was deemed expedient to ransfer the sees of the Bishops from villages and small towns to more significant towns. William of Malmesbury gives the same explanation. The consequnce of this was that see of Lichfield was moved to Chester:

- "Ordinatum est, quod sedes episcoporum de viculis transirent ad urbes majores; unde factum est ut sedes Lytchfeldenis transirit ad Cestriam"

William of Malmesbury states that a decree was signed on the festival of Pentecost in the year 1072 which ordained:

- "..that according to the cannons the bishops should quit the villages and fix their abode in the cities of their dioceses: Lichfield, therefore migrated to Chester and, amongst others, Dorchester to Lincoln."

Peter had been a royal chaplain before being nominated to the see of Lichfield. Nothing else is known of his background, although presumably he was a Norman, as were most of King William I of England's episcopal appointments. He may have been a royal clerk of King Edward the Confessor, although one charter of 1065 which lists his name is a forgery. He was the custodian of the see of Lincoln, before his elevation to the episcopate.

Interestingly, Ralph de Diceto makes a statement to the effect that Chester was an episcopal see before ether Lichfield or Coventry. Diceto devides church history into three phases with the see in the time of the Britons at Chester; in the Saxon era at Lichfield and after the Danish and Norman invasion at Coventry.

- "In ea quidem diocesi plures ab antiquo sedes habitae sunt episcopales: temporibus Britonum, apud Cestriane: temporibus antiquorum Saxonum apud Lytchesfeldian - temporibus Danorum et Normannorum apud Coventreiam."

If it was truly the case that Chester was the seat of the church in England in pre-Saxon times, then it makes some sense that the famous meeting with the English Bishops and Augustine took place in Chester. And that Augustines "prophecy" was fulfilled at Heronbridge in the Battle of Chester (indeed the c1900 stained glass at St John's records the deaths of the Monks of Bangor):

- And her Æðelfrið lædde his færde to Legercyestre, & ðar ofsloh unrim Walena. & swa wearþ gefyld Augustinus witegunge. þe he cwæþ. Gif Wealas nellað sibbe wið us. hi sculan æt Seaxana handa farwurþan. Þar man sloh eac .cc. preosta ða comon ðyder þæt hi scoldon gebiddan for Walena here. Scrocmail was gehaten heora ealdormann. se atbærst ðanon fiftiga sum. (a rather free translation reads...And here Æthelfrith led his militia to the castle of the legions (Chester), and there slew innumerable Welsh. And so was fulfilled Augustinus's prediction (prophecy), that he said give the barbarians no peace with us, they shall owe their death to the hands of the Saxons. There were slain also 200 priests that came in order to pray for the Welsh soldiers. Brochfael was called their leader, and he escaped as one of fifty.)

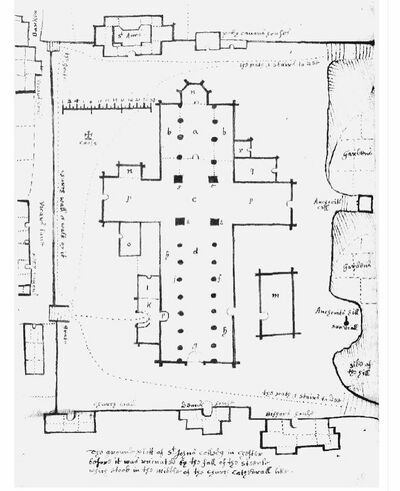

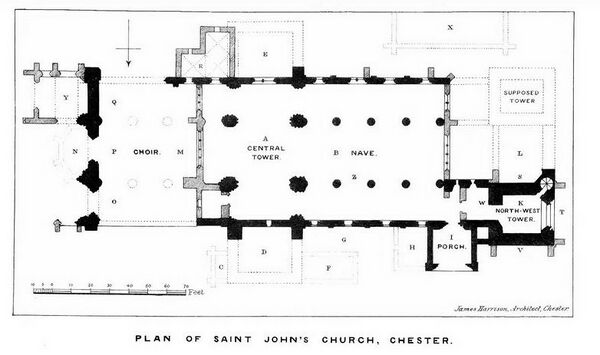

The old St John's just would not do as the home of an important bishop, and so had to be rebuilt. The basic plan of the new church followed the standard Norman design, with a choir to the east, a central crossing with a tower above, transepts, a nave to the west and a pair of towers at the western end. However not all of this was to be completed. De Leia died and was buried in Chester in 1085. His successor Robert de Limesey translated his see from Chester to Coventry in 1102. Robert was one of the bishops, along with Gerard, Archbishop of York and Herbert de Losinga bishop of Norwich, who returned from Rome (in 1102) and informed Henry I that Pope Paschal II had confirmed Henry could personally invest bishops, "provided they were good men". This was during the Investiture Controversy, and the pope later denied what had been said and excommunicated all three bishops.

It is probable therefore that the early Norman part of this church belongs to the period between 1075 and 1102. The massive piers and semicircular arches of the nave belong to this period but the triforium and clerestory built upon them are of transitional character and belong to the end of the twelfth century and the 1200's. It appears that when the second Norman bishop in 1102 removed the see to Coventry and abandoned the plan of making this church the cathedral of the three united dioceses of Chester, Lichfield and Coventry that the fabric of the church was left very incomplete. The bishop also removed the funds on which its completion depended leaving the monks of the Priory of St John were left forlorn state with a large church commenced, and little more than commenced. While the external fabric of the church is largely Early English in style due to later restorations, much of the interior still consists of Norman stonework. This is believed to be present in the nave, the crossing, the first bay of the chancel, the arch to the Lady Chapel and in the remains of the choir chapels. Work had been carried on for about twenty years but that was comparatively a short period according to the custom of that age when a large church was commonly a century in the course of erection and the rebuilding in a new style was often commenced before the original plan was completed as was probably the case in the rival church of St Werburgh. Before the bishop deserted St John's the whole of the foundations had probably been laid but no part finished unless possibly the choir which was afterwards rebuilt.

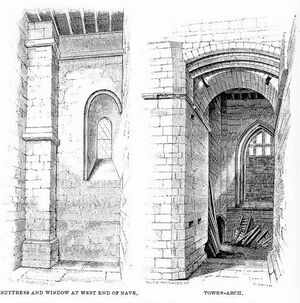

The Norman work includes the arches and piers of the 4-bay nave. The piers are plain circular extremely massive columns on cruciform bases; varied scalloped capitals and twice rebated voussoirs. The arches are merely recessed with square edges without any mouldings. The four great arches which carried the central tower with shafts attached to the piers are of the same character as those of the nave and one bay of the choir with its aisles. On the north side this bay of the aisle is turned into a modern vestry but over it is one of the arches of the triforium arcade (c1190) which is of the same plain early character as the nave - 4 arches on bay piers with 5 attached colonnettes and intermediate piers with 3 colonnettes. On the south side the first bay of the aisle is tolerably perfect and is richer work of rather later date than the rest. There is an ornamental arcade at the foot of the wall and a window over it these are of very good pure Norman work but not quite so early a character as the nave arches. The arcade columns lean outward and westward; the angle of lean which increases from crossing to third columns, then begins to decrease, is carried up through triforium and clerestory; the present height above floor level of successive pairs of columns suggests that orginally the nave floor sloped upward towards the crossing. The diagonal lean of the arcade columns is evidently deliberate. The plinths on which they stand have vertical sides and, beneath the recessed padstones, level tops; the padstones are tapered from inner east corners to the outer west corners, to give appropriately sloping beds for the columns.

The arches opening from the choir to the aisles are also enriched with bold round mouldings while those of the nave have none. In the aisle the springing of the Norman vault may be seen but it does not appear to have been completed. The outer wall of this aisle is continued along a second bay with a continuation of the small arcade and a second window of the same pattern as the one in the first bay. On the exterior this window is richly ornamented with zigzags and shafts and is turned into a doorway the exterior of the first window is hid by a modern chimney but is probably the same.

Exactly what was built when has been the subject of much debate:

- Parker (1855-62) believed the building was begun in the late 11thc., attributing the choir arcades, the transepts and the main arcades at the east and west end of the nave to a period of late 11th and early 12thc. He considered that the central section of the nave arcade had been completed last, and that the choir aisles were either delayed in their completion or rebuilt later. He dated the upper storeys of the nave to c.1190.

- Pevsner & Hubbard suggest a starting date before 1095, and date the nave triforium to c.1190 or later and the clerestorey to the 13thc.

- Clapham (1934), suggested that the church was not begun much before 1130-40. He was to modify this in 1937, dating the inception of work 'not before the first half of the 12thc.', and the nave arcade to the third quarter of that century.

- Gem (2000) has the entire original eastern arm built 1100-17), the crossing arches and the nave arcade built 1125-50) and the nave triforium and clerestorey late 12thc. and early 13thc. There appears to have been a break in the building between the triforium and the clerestory. The triforium includes waterleaf, stiff-leaf and moulded capitals, suggesting a date in the 1190s; while the clerestorey capitals are predominantly stiff-leaf with some moulded forms, pointing to a date in the 1200's.

The Chapter House

The only other medieval part of the church is the somewhat enigmatic two-storey structure of c.1300 built in the angle between the south transept and the choir and accessed through a doorway in the south choir aisle. Its undercroft is square and vaulted in four bays with a central pier: the upper storey has lost its roof. Locally it is known as the "Chapter House", but neither its form nor its position make this very likely, and it has been suggested that it was a two-storey treasury. In the early 19thc. it was incorporated as a kitchen into the large brick and stucco Priory House (now demolished) which became the residence of Thomas de Quincey's mother. Priory House was the home of Robert Grosvenor when he was Mayor of Chester in 1808. Priory House was demolished in 1871.

In 1796, three years after the death of his father, Thomas Quincey, Thomas de Quincey's mother – the erstwhile Elizabeth Penson – took the name "De Quincey". In 1800, De Quincey, aged fifteen, was ready for the University of Oxford; his scholarship was far in advance of his years. "That boy," his master at Bath had said, "could harangue an Athenian mob better than you or I could address an English one." He was sent to Manchester Grammar School, in order that after three years' stay he might obtain a scholarship to Brasenose College, Oxford, but he took flight after nineteen months. His first plan had been to reach William Wordsworth, whose Lyrical Ballads (1798) had consoled him in fits of depression and had awakened in him a deep reverence for the poet. But for that De Quincey (aged 17) was too timid, so he made his way to Chester, where his mother now dwelt, in the hope of seeing his sister, Mary.

Thomas bungled the attempt to see his sister secretly and was aprehended by the older members of the family. Through the efforts of his uncle, Colonel Penson, he received the promise of a guinea (£1.05) a week to carry out his later project of a solitary tramp through Wales. From July to November 1802, De Quincey lived as a wayfarer. He soon lost his guinea by ceasing to keep his family informed of his whereabouts, and had difficulty making ends meet. Still apparently fearing pursuit, he borrowed some money and travelled to London, where he tried to borrow more. Having failed, he lived close to starvation rather than return to his family. Discovered by chance by his friends, De Quincey was "brought home" and finally allowed (1803) to go to Worcester College, Oxford, on a reduced income. By his own testimony, De Quincey first used opium in 1804 to relieve his neuralgia; he used it for pleasure, but no more than weekly, through 1812. It was in 1813 that he first commenced daily usage, in response to illness and his grief over the death of Wordsworth's young daughter Catherine. So while De Quincey presumably stayed at the house in Chester for a short periods, this was before his notorious "opium-eating".

Perhaps De Quincy was thinking of the founding of St John's when he wrote:

- "Such traditions, or any others that (like the stag) connect distant generations with each other, are, for that cause, sublime; and the sense of the shadowy, connected with such appearances that reveal themselves or not according to circumstances, leaves a colouring of sanctity over ancient forests, even in those minds that utterly reject the legend as a fact."

His mention of Priory House in his "Confessions of an English Opium-Eater" describes the property:

- "St. John's Priory had been part of the monastic foundation attached to the very ancient church of St. John, standing beyond the walls of Chester. Early in the 17th century, this Priory, or so much of as remained, was occupied as a dwelling-house by Sir Robert Cotton, the antiquary. And there, according to tradition, he had been visited by Ben Jonson.. .. In this condition of attractiveness my mother saw this little Priory, which was then on sale. As a residence, it had the great advantage of standing somewhat aloof from the city of Chester, which however (like all cathedral cities), was quiet and respectable in the composition of its population. My mother bought it, added a drawing-room, eight or nine bedrooms, dressing-rooms, etc., all on the miniature scale corresponding to the original plan : and thus formed a very pretty residence, with the grace of monastic antiquity hanging over the whole little retreat."

It also describes his "escape attempt" and an encounter with the Dee Bore:

- "But at the very door of the I was suddenly brought to a pause by the recollection that some of the servunts from the Priory were sure on every forenoon to be at times in the streets. The streets, however, could be evaded by shaping a course along the city walls ; which I did, and descended into some obscure lane that brought me gradually to the banks of the river Dee. In the infancy of its course amongst the Denbighshire mountains, this river (famous in our pre-norman history for the earliest parade of English monarchy) is wild and picturesque ; and even below my mother's Priory wears a character of interest. But, a mile or so nearer to its mouth, when leaving Chester for Parkgate, it becomes miserably tame ; and the several reaches of the river take the appearance of formal canals. On the right bank of the river runs an artificial mound, called the Cop. It was, I believe, originally a Danish work; and certainly its name is Danish (i. e., Icelandic, or old Danish), and the same from which is derived our architectural word coping. Upon this baulk I was walking .. ..there was nobody at all, except one woman, apparently middle-aged (meaning by that from thirty-five to forty-five), neatly dressed, though perhaps in rustic fashion, and by no possibility belonging to any class of my enemies; for already I was near enough to see so much. This woman might be a quarter-of-a-mile distant ; and was steadily advancing towards me — face to face. Soon, therefore, I was beginning to read the character of her features pretty distinctly ; and her countenance naturally served as a mirror to echo and reverberate my own feelings, consequently my own horror (horror without exaggeration it was), at a sudden uproar of tumultuous sound rising clamorously ahead. Ahead I mean in relation to myself, but to her the sound was from the rear. Our situation was briefly this. Nearly half-a-mile behind the station of the woman, that reach of the river along which we two were moving came to an abrupt close ; so that the next reach, making nearly a right-angled turn, lay entirely out of view. From this un-seen reach it was that the angry clamor, so passionate and so mysterious, arose : and I, for my part, having never heard such a fierce battling outcry, nor even heard of such a cry, either in books or on the stage, in prose or verse, could not so much as whisper a guess to my-self upon its probable cause. Only this I felt, that blind, unorganized nature it must be — and nothing in human or in brutal wrath — that could utter itself by such an anarchy of sea-like uproars. What was it ? Where was it? Whence was it? Earthquake was it? convulsion of the steadfast earth? or was it the breaking loose from ancient chains of some deep morass like that of Solway?.. ..Not long I needed to speculate; for within half-a-minute, perhaps, from the first arrest of our attention, the proximate cause of this mystery declared itself to our eyes, although the remote cause (the hidden cause of that visible cause) was still as dark as before. Round that right-angled turn which I have mentioned as wheeling into the next succeeding reach of the river, suddenly as with the trampling of cavalry — but all dressing accurately — and the water at the outer angle sweeping so much faster than that at the inner angle, as to keep the front of advance rigorously in line, violently careered round into our own placid watery vista a huge charging block of waters, filling the whole channel of the river, and coming down upon us at the rate of forty miles an hour."

What remained of the "treasury" was renovated in 1937 and the undercroft taken over in 1939 as a public air-raid shelter. It now serves as a stone store and was photographed in some detail in 2014 as shown here.

The Rood of Chester

From the 13th century St. John's reputation was enhanced by the possession of an important relic, the so-called "Rood of Chester" ('Rood' means cross, but is from the Anglo-Saxon word for 'rod/pole'). This relic existed by 1256 or 1257, when Fulk de Orby, Justicar of Chester, provided a mark of silver annually for lights before it, and appears to have been enshrined in a golden cross-shaped reliquary adorned with an image. It was so greatly venerated both in the locality and much further afield that in the late 13th and early 14th century St. John's was known as the "Church of the Holy Cross". Cheshire seems to have been littered with fragments of the True Cross. Edward I gave the abbey of Vale Royal a portion of the True Cross upon its foundation which he had "violently carried off" from the holy land. As well as that at Chester there was one at Norton Priory provided by another participant in Ranulf’s crusade retinue: Geoffrey de Dutton

Swearing on the "Rood of Chester" turns up frequently in literature. An abiding mystery is what became of this venerated relic. The cross at St John's was the local "star" of the cult of relics which has been described as the true religion of the middle ages. Miraculous cures were sometimes attributed to the shrine of St Werburgh and her "girdle" was "said to be in great request by lying-in women" - but St John's cross overshadowed all other relics. They certainly needed one to rival the one at Vale Royal.

According to one version, the cross itself appears to have been a silver-gilt crucifix supposedly containing wood from the "True Cross". Its origins are uncertain. Some have suggested it was brought from the East by Ranulf de Blondeville, who was on Crusade in 1219-20. It should be noted in passing that if Ranulph had assembled all the bits of the so-called "True Cross" available in the middle-east during the crusades, he could have built himself a fair sized ship to sail home in. It has also been suggested that this relic may have been associated with the cult of King Harold, boosted in 1332 by the discovery within the church of his alleged remains (see Hermitage). Harold's links with the "Cult of the Holy Rood" and in particular with the allegedly miracle-working crucifix of Waltham (Essex), perhaps suggested the introduction of an analogous "relic" in Chester. The town of Waltham was traditionally founded by Tovi or Tofig, when he built a wooden church to house the miracle-working crucifix (The Holy Cross) discovered on his estate in Somerset. The wooden church was later replaced by one of stone by Earl (later King) Harold, who was traditionally buried here after the Battle of Hastings. Another well-known "Rood" features in the early Anglo-Saxon poem "Dream of the Rood" believed to date from around 660.

The relic is also mentioned in the story "Wallingford Castle" was printed in the Metropolitan Magazine (see volume III, January June 1837 page 410) the story also mentions the seemingly entirely fictional "finger of St Martin") where the suggestion is made that the relic was carried by Harold at the battle of Senlac Hill:

- "By the spear of St Michael my lady empress said the Earl of Chester looking fearfully round as the old man suddenly disappeared that piece of the true cross is a relic of marvellous power St Mary twas well ye had it around your neck when ye rode that black steed and journeyed thither for see ye not that the sight of that holy reliquary alone hath forced that old sorcerer to flee away O marvellous is the efficacy of the holy cross ... I will send to the abbey at Chester for the finger of St Martin that may secure me in some measure but saints know I would right gladly pay two score pounds of pure silver for a sliver of the true cross."

The Earl of Chester mentioned in the story would be the serial turn-coat Ranulph De Gernon and the "finger of St Martin" seems completely fictional, although there was a St Martin in Chester of very early date and Lucian the Monk mentions this saint was revered in the city.

By the early 14th century at least one of the ships which plied from Chester (the property of William (III) of Doncaster) was known as the "Holy Cross of Chester". In the 14th century the oath "by the Rood of Chester!" was evidently commonplace, being mentioned in both William Langland's great poem the "Vision of Piers the Ploughman" (see part V line 5.460):

- " And yet wole I yelde ayein. [y]if I so muche have, Al that I wikkedly wan sithen I wit hadde; And though my liflode lakke, leten I nelle That ech man shal have his er I hennes wende; And with the residue and the remenaunt, bi the Rode of Chestre, I shal seken truthe erst er I se Rome!"

It also turns up in the less famous "Richard the Redeless" ("For reson is no repreff, be the rode of Chester." - i.e "for reason is no reprieve, by the Rood of Chester!").

The relic was especially venerated in Wales; in 1278, 10 hostages from the leading men of Gwynedd were released after swearing loyalty (on the Rood) and that they would not bear arms against the king, and in the later 14th century it was the subject of several odes by the poet Gruffudd ap Maredudd (1352–1382), who seems to have made a pilgrimage to the relic, and others.

At their height, offerings to the "Rood" amounted to perhaps £70 a year and constituted by far the biggest item in the revenues of the church. The highwatermark of the relic's popularity was reached in the mid 14th century. Gifts continued to be made to it throughout the later Middle Ages: a ring in 1467, £20 from the son of a former mayor in 1489, and five large candles from an alderman in 1505. In the early 16th century a man from Winwick (Lancs.) left 6s. 8d. to anyone willing to undertake a pilgrimage to the "Rood" on his behalf, and the courtier William Smith caused three gold marks to be offered for the soul of his late master, Henry VII. As late as 1518 Nicholas Deykin made provision for a priest to celebrate at the "Altar of the Holy Rood" for eight years after his death. Hemingway writes:

- "Dr Cowper in his Penseroso says In this church was an ancient rood or image of wood of such veneration ihat in a deed March 27 1311 confirmed by Walter Langton the church was called The Church of the Holy Cross and St John Richard Hawarden of Winwick Lancashire by will dated March 28 AD 1503 left VIs VIIId to whatever priest would go for him to the Holy Rood at St John's Chester"

The relic was removed in the 1530s (according to Douglas Jones' "The Church in Chester, 1300-1540", in 1541) and thereafter passes into obscurity (or see below) - the removal of relics was a feature of the Reformation. Lancelot Ridley, writing in 1540, rages against this and other examples of "idolatry":

- "As some ignorant persons have in times past thanked God for their health and the blessed Lady of Walsingham of Ipswich St Edmund of Bury Etheldred of Ely the Lady of Red bone the holy blood of Hayles the holy Rood of Begles of Chester and so of other images in this realm to the which hath taen much pilgrimage and much idolatry supposing the dead images could have healed them or have done something for them to God for the which the ignorant have crouched kneeled kissed bobbed and licked..."

Much the same appears in Foxe's book of Martyrs:

- "What should I speak of Darvel Gartheren, of the rood of Chester, of Thomas Becket, of our lady of Walsingham with an infinite multitude more of the like affinity all which stocks and blocks of cursed idolatry Cromwell stirred up by the providence of God removed them out of the people's way ...."

The reference to "Darvel Gartheren" is to Llandderfel another church on the River Dee which has a stag-based foundation legend and was associated with a wooden relic.

In January 1538, Thomas Cromwell pursued an extensive campaign against what was termed "idolatry" by the followers of the new Protestant religion. Statues, rood screens and images were attacked, culminating in September with the dismantling of the shrine of St Thomas Becket at Canterbury. Early in September, Cromwell also completed a new set of vicegerential injunctions declaring open war on "pilgrimages, feigned relics or images, or any such superstitions" and commanding that "one book of the whole Bible in English" be set up in every church. The iconoclastic volence undertaken by Parliamentary soldiers during the Civil War, particularly against cathedral churches, became notorious. Much the same sort of behaviour is seen among certain fundamentalist groups in modern times. In Chester this also led to the destruction of the High Cross. The "Committee for the Demolition of Monuments of Superstition and Idolatry" on the Parliamentary side was probably not that much different to the people who would demolish the walls of Nineveh and flatten Nimrud - it is always true that those who refuse to learn the lessons of history often seek to erase it.

As was noted in "An Ordinance for the further demolishing of Monuments of Idolatry and Superstition":

- "The Lords and Commons assembled in Parliament, the better to accomplish the blessed Reformation so happily begun, and to remove all offences and things illegal in the worship of God, do Ordain, That all Representations of any of the Persons of the Trinity, or of any Angel or Saint, in or about any Cathedral, Collegiate or Parish Church, or Chappel, or in any open place within this Kingdome, shall be taken away, defaced, and utterly demolished; And that no such shall hereafter be set up, And that the Chancel - ground of every such Church or Chappel, raised for any Altar, or Communion Table to stand upon, shall be laid down and levelled; And that no Copes, Surplisses, superstitious Vestments, Roods, or Roodlons, or Holy-water Fonts, shall be, or be any more used in any Church or Chappel within this Realm; And that no Cross, Crucifix, Picture, or Representation of any of the Persons of the Trinity, or of any Angel or Saint shall be, or continue upon any Plate, or other thing used, or to be used in or about the worship of God; And that all Organs, and the Frames or Cases wherein they stand in all Churches or Chappels aforesaid, shall be taken away, and utterly defaced, and none other hereafter set up in their places; And that all Copes, Surplisses, superstitious Vestments, Roods, and Fonts aforesaid, be likewise utterly defaced; whereunto all persons within this Kingdome, whom it may concern, are hereby required at their peril to yield due obedience."

Hemingway, writes of a surviving document "written in Norman French upon a square piece of vellum to which two seals are appended much decayed and is in possession of Mr Thomas Walshman of this city". A translation of the document is quoted in Hemingway and given below:

- "John Gosvenor Constable of Fronssac and Henry Van Emeric Provost of the said place for our very sovereign lord the King of England and France and for the very honoured and powerful lord Mr Thomas Swynbourne Mayor of Bourdeux Captain of the said place of Fronssac for our said lord the king to all those who these present letters shall see or hear in causing it to be known how that the praiseworthy man Henry Champaigne Esquire and Burgess of the town of Libourne a long time before his departure from this world proposed and devoutly intended to transmit into England to the city of Chester a great shrine of gold in which there was a piece of the holy cross on which our Saviour formerly underwent his passion according as he said and was truly informed by honourable people of the Holy Church who knew and were well acquainted with that relique when the very reverend Father in God the good Cardinal de Perigord kept it in bis treasury and caused it to be honoured as a relique of the cross of our Saviour and so the said Henry Champaigne had a firm faith and devout belief in that relique and on his departure from this world he ordered and charged his wife and executors and his other chief friends that that relique should be carried to the said city of Chester that it might be placed in the county of that city and he willed for the love and honour which he bore to the said city that it should be carried there and presented and not placed elsewhere and that the good people should have devotion for it and remembrance of his soul The which holy relique was by the order of his wife and of his executors and other his friends transmitted and presented to the aforesaid city of Chester by Nandon de Prey a burgess and merchant of the said town of Libourne And these things we certify to all to be true without any doubt It witness of the truth and foi the greater confirmation of the things above-said we the aforesaid John Gosvenor and Henry Van Emeric to these present letters have put our own seals Given at Fronssac the 6th day of December in the of our Lord 1411."

Documents in the national Archives have one 'John Grosvenor' as the 'Constable of Fronsac' at that time, but these dates make little sense as the relic was supposedly already in Chester long before 1411.

Writing in 1662 William Rowley may have made a reference to the Rood of Chester in his play "The Birth of Merlin" (this features a "Holy Hermit of Chester" - aparently called 'Anselm') and the lines:

- Edol of Chester is a noble soldier - so he is by the Rood.

This is a very mysterious reference as "Edol of Chester" is only mentined in one other place in literature and that (by Hollinshead) is in connection with the Saxons and Vortigern (see Dark Ages). Also Anselm of Bec (in 1092) came from France to England to found the Benedictine Abbey at Chester during the time of Earl Hugh of Avranches. Finally, it shouldn't be forgotten that the cross which, according to legend, gave the Roodee it's name was said be some to have been taken to St John's. Another source gives a different source and fate for the 'relic'. According to "The Gentleman's Magazine" (May 1825):

- Archdeacon Rogers gives a curious account of a wooden image formerly preserved here. It appears a statue of the Virgin was set up in the Castle of Hawarden in Flintshire about six miles from Chester which owing to the negligence of the artist fell down on the head of Lady Trawst the Governor's wife and killed her. An inquest was impanelled and the Jury condemned the image to be thrown into the River Dee. Sentence was accordingly executed and the tide washed it up to Chester and left it on that fine meadow called Rood eye on the race course. It was taken down from thence with great solemnly to St John's Church where it was long an object of pious adoration but the Reformation intervened and this sacred relic of superstition which had been so much honoured was converted into a block for the Master of the Grammar School to flog his refractory scholars upon and was subsequently burnt.

Pigot wrote:

- "The curious and ancient records handed down through the medium of Archdeacon Rogers's Manuscripts in some degree conflrm the ahove extraordinary anecdote but it is there stated to have heen a wooden cross which causing the lady's death was thrown into the sea and floated up to Chester - also that the said cross was with great solemnity placed in St John's Church. After the Reformation, it is said this cross was converted into a block for the Master of the Grammar School to whip his scholars on "to such base uses do we come at last" and after some time was committed to the flames."

Archdeacon Rogers - apparently lived in Chester (died 1595) - also gave a description of the Mystery Plays and is normally considered a reliable source. And Pigot appears to be (mis-)quoting Shakespeare:

- "To what base uses we may return, Horatio. Why may not imagination trace the noble dust of Alexander till he find it stopping a bunghole?".

Whether with income from their relic or money from other sources, building of the church got under-way again in the 1200's. In the late 12th century the Early English Gothic style had superseded the Romanesque or Norman style, and during the late 13th century it developed into the Decorated Gothic style, which lasted until the mid 14th century. In keeping with the evolution from the Romanesque style to the English Gothic, the four bays of the triforium, each have arcade of four pointed arches, rather than the rounded Norman arches seen below. It is said that the innovation of the pointed arch was brought back from the crusades and borrows the style used in Arab architecture.

The early C13 clerestory repeats the triforium rhythm, but with mouldings more developed than those on the stonework below.

Courtroom

The Scrope Case

Collins Peerage of England states:

- Among the attendants of the said William, Duke of Normandy, in that victorious expedition into England, were his two uterine brothers, Robert, Earl of Mortaigne in the duchy of Normandy (who afterwards got the earldom of Cornwall), and Odo, Bishop of Bajeux, in the said duchy (created Earl of Kent in 1067) with Hugh Lupus, Count of Avranches, who by his mother was their nephew (of whom mention will be made as Earl of Chester) and Gilbert le Grosvenor, nephew to the said Hugh; as is evident from a record, preserved in the Tower of London, concerning a famous plea (which shall in its proper place be taken due notice of), in a court of chivalry, with relation to a Coat of Arms claimed by Sir Richard le Scrope (who had been Lord High Chancellor of England in 1382) and Sir Robert le Grosvenor

The claim to a family link to the Original Hugh Lupus (Hugh of Avranches) and the Grosvenors has been the subject of much debate. There are several problems with the claim, not least of which being that given the young age of the original Hugh Lupus at the time of the Norman Conquest nephew "Gilbert" (who seems to be mentioned nowhere else) would have had to be remarkably young at the time of the invasion and it is surprising that this is not recorded. The name "Venour" does turn up in the records at Battle Abbey and this has been suggested as a possible indication that "Gilbert (gros) Venour" (Gilbert the fat hunter) might have existed - although it is unlikely he was Hugh's nephew.

In the heraldic case of Scrope v. Grosvenor (1389), Grosvenor maintained his ancestor, Gilbert, had come to England with William the Conqueror. The case was brought before a military court and presided over by the constable of England - and the first sitting of the Court of Chivalry in the which decided the Scrope/Grosvenor Armorial Bearings was held at St Johns. Several hundred witnesses were heard and these included John of Gaunt, King of Castile and Duke of Lancaster, Geoffrey Chaucer and a then largely unknown Welshman called Owain Glyndŵr. The witnesses for Grosvenor stated that:

- ..it was generally reputed in the counties bordering on North Wales that his ancestors had borne the arms azure a bend or from the time of Sir Gilbert de Grosvenor a follower of Hugh Lupus Earl of Chester who was nephew to the Conqueror and that the said arms were to be seen in windows and on tombstones in several churches of Cheshire

The Abbot of the Cistercian Abbey Vale Royal spoke still more positively to the pedigree and arms of Grosvenor saying expressly:

- ..that he has it from chronicles and ancient writings in his monastery that Sir Robert Grosvenor descended in direct line from Gilbert le Grosvenor who in the train of his uncle Hugh Lupus came over with the Conqueror armed in the said arms which he used to the time of his death

In 1389 the case was finally decided in Scrope’s favor - but Grosvenor was allowed to continue bearing the arms within a silver border. Neither party was happy with the decision, and in 1390 Richard II decided these shields were too similar for unrelated families in the same country to bear. Grosvenor switched to the blue shield with the golden sheaf of corn. The sheaf of corn is interesting, because it first appears in English heraldry on the arms of Hugh de Kevelioc a later Earl of Chester who was infamous for revolting against the king, and the same "garb" was also used by his son Ranulf de Blondeville (a rather more noble knight). There is a very poor representation of the original earl Hugh of Avranches arms in Ormerod's history, and it is possible that this was mistaken for a sheaf of corn (when actually it is a wolf's head).

The controvery over "Bend Or" rose again in a different way when the first Duke of Westminster was accused of "switching" a racehorse of the same name. Although it could not be proved at the time, recent DNA evidence shows there was indeed a switch. Indeed the "Sherlock Holmes" story "Silver Blaze" may well be based on this switch.

The Minstrel Court

St John's was also involved in the Minstrel Court which dates from the time of Ranulf de Blondeville and his rescue from Rhuddlan Castle by minstrels and various others (as depicted at the Town Hall), the last such court was held in 1756. It is described as follows in "The Patrician" (1848) edited by John Burke, Bernard Burke:

- *The procession then moved forward to the church of St. John the Baptist. On entering the church, the steward made a signal to the musicians, who instantly dropped on their knees, and proceeded to play sundry solemn airs upon their instruments. Divine service was then performed, and the Lord of Dutton was specially prayed for. Service being over, the proclamation was made, and the procession then returned to the inn, in the same order as it came. Entertainments to the Lord's friends and musicians followed, and in the afternoon a jury was impanelled from among the licensed musicians, when the steward delivered a charge. The jurors then gave in their verdicts."

Among the tax collections which were made at the court was also

- "an annual payment of four pence from every female of a certain notoriety within the county of Chester".

The creation of the bishopric of Chester in 1541 provided a fresh threat to St. John's. The archdeacon's court, hitherto held in the collegiate church, was removed in that year to the Cathedral. Although the dean's claim to be exempt from the authority of the new bishop was recognized in 1542, the privilege was soon lost. Thereafter, the college seems to have feared the worst, and disposed of property in a series of very long leases. Finally, in 1547 or 1548 the college, with its staff of dean, seven canons (five with livings elsewhere), and four vicars, was dissolved.

Collapse

Warnings of Disaster

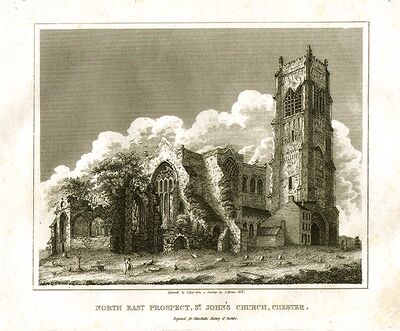

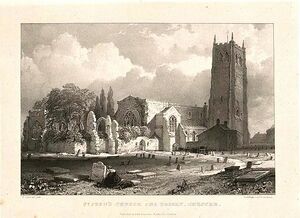

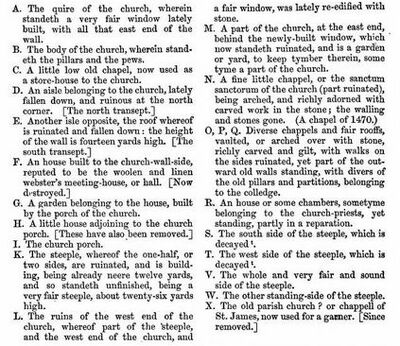

If the cross which killed Lady Trawst did get transported to St John's, then it's "curse of falling down" may have moved with it. In 1468 the central tower collapsed destroying a great part of the choir. The steeple was rebuilt in 1470. At the end of the nave two bays are wanting of which the foundations only were laid. Of two large western towers one at the west end the foundations only of the southern had been laid and this tower was in fact, never built. The northern tower had made more progress. The lower story is Norman but the tower was completed in the time of Henry VII (1485 - 1509). By about 1550, the church was reduced in size. The transepts were entirely destroyed at the Reformation when the size of the church was reduced to adapt it for parochial use only. Those parts of the church which were no longer in use had the lead removed from their roofs and "given" to the king, while all of the bells save one were removed.

The rebuilt central steeple lasted until 1572, when the steeple again collapsed. Ormerod writes:

- "..in 1572 a great portion of the of the whole steeple from top to bottom fell upon the west end of the church and broke down a great part of it".

In 1572 it seems that there was also a partial collapse of the north-west tower and in 1574 there was a greater collapse of this tower which destroyed the western bays of the nave. This was repaired around 1581. Hemingway writes:

- "1581 - The parishioners of St John's having obtained the said church of the queen began to build some part of it again and cut off all the chapels above the choir."

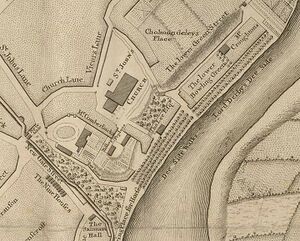

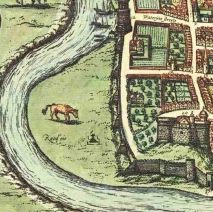

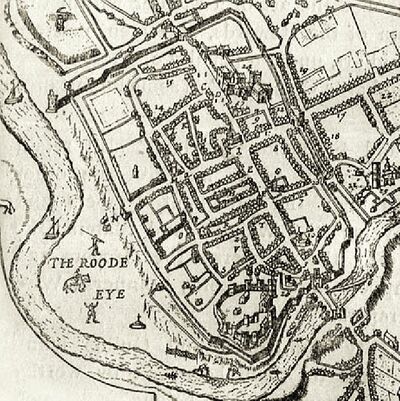

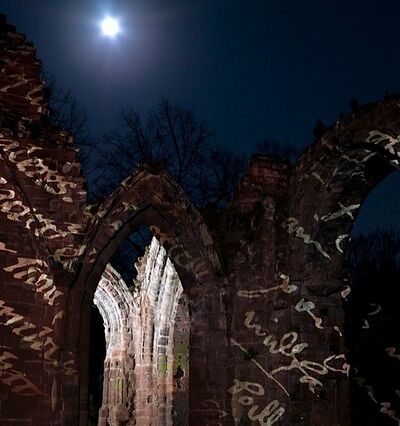

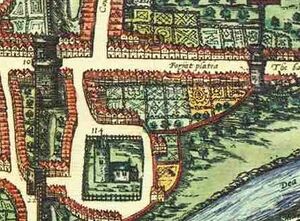

The Braun and Hogenberg map (from around 1581) of Chester shows St John's with an intact north-western tower, no central spire and the ruins of the choir to the east. However the John Speed Map of Chester (1605) appears to show the church with a central spire still in place. Speed's map also shows Little St John Street curving round the amphitheatre and contains valuable clues as to the extent of the buildings and the religious enclave. It is especially important because some of the features on it can be traced on later mapping, and some still exist today as walls and boundaries.

The church was kept in good condition in the earlier 17th century, but suffered severe damage, especially internally, after its capture by the parliamentarians. During the siege of Chester (1645-46) in the Civil War, the north-west tower was used to mount a gun battery. The weight of the guns and the shock of their discharge must have done much to weaken the structure. Packets of papers were also shot over the city walls, encouraging the towns folk to surrender. When this failed, snipers were placed at the church tower's summit. From here they were able to take pot shots at anyone seen in the streets beneath them, and succeeded in shooting and killing Sheriff Randle Richardson. A sniper on St John's tower also managed to shoot dead a captain standing next to Charles I when they were "skylined" while standing on the Cathedral tower watching the conflict that had started at Rowton Moor. Finally, on the 31st of January 1646 the city of Chester surrendered, agreeing terms on the 1st of February. In 1646 the minister was deprived and replaced by a parliamentarian pastor, Peter Leigh, who in 1648 signed the Cheshire attestation of Presbyterian ministers. Under his regime much effort was expended in making the interior fit for the new forms of worship, and the church acquired seats from the cathedral and a basin to replace the discarded font. Leigh was ejected in 1662 and replaced by Alexander Featherstone, a pluralist soon accused of "leading a scandalous life".

Despite restoration in 1646 and further work on the tower in 1660, the chancel was out of repair in 1665. By 1719 the minister and churchwardens had to seek assistance for major repairs, including reroofing and rebuilding the aisle walls and steeple. A brief was issued, which by 1720 had raised over £1,200, and in 1728 the church was said to be in good condition. George Cooke, writing in 1806 describes how the church displays "the ravages of time".

Hanshall, in 1816 noted the previous use of the tower as a gun battery and records:

- In the month of June 1814 a cannon ball weighing about five pounds was found by the Sexton in digging a grave at the West end of the North aisle of the church It was much corroded by time. The ball was shewn to us by the respected Vicar, the Rev W Richardson, in whose possession it now is.

Hemingway, writing in 1836 describes the west tower as follows:

- "The tower about 150 feet high and detached from the body of the church contains an harmonious set of eight bells six of them cast in 1710 and two in 1734 The approach to it is through the remains of the north aisle The sides of the tower are decorated with a rich screen and ornamented with figures placed in niches of equisite workmanshop"

Oddly, Hemingway says nothing about the already decayed state of the west tower. Bentley's Miscellancy (1837) describes St Johns as follows (with clear indications that something is amiss with the foundations):

- The most ancient of the churches of Chester is that of St John or the Holy Cross founded by the Mercian King Ethelred at a period when the opposite shores of the Dee were clothed with forests long since removed. From the city walls as the spectator looks down the tower seems still to rise to its stupendous height from a thick grove for an orchard filled with luxuriant trees interposes between the church and the ramparts. The tower is seen from all quarters vying in height with that of the more massive and squarer one of the cathedral. The tower and body of the church the arches and the numerous ruins attached to this singular old building all seem to be in the very act of sinking down into the earth which is piled with gravestones round them. A more venerable battered mysterious inexplicable time worn piece of architecture than the bell tower and ruins of St John's of the Holy Rood of Chester can seldom be met with. One principal doorway black with time and weather scarcely lifts the capitals of its supporting pillars out of the ground it must have sunk at least five feet and the same is the case with all the arches in the town which occasions them to present a most ghost like unearthly aspect which almost makes the beholder shudder.

Seacome (1828) is quite disparaging:

- "The whole interior presents an interesting relic of the architecture of our Saxon ancestors combined with that of their Norman English successors. The woodwork is very plain and the pews are not only mean but uncomfortable added to which the want of an organ throws additional discredit upon the wealthy inhabitants of this parish."

In 1838, the church organ was installed. This was no ordinary organ, as earlier in the same year it has been built in the workshops of Hill and Davison for the coronation of Queen Victoria in Westminster Abbey (using many of the same rites that were devised by Dunstan for the coronation of Edgar). The organ was rebuilt before being transported to Chester (by canal barge).

Samuel Lewis, writing in 1848 says:

- "The nave has massive Norman piers, with a triforium and clerestory of early English character; the north porch, in the same style, is very beautiful: the tower, a fine composition though greatly mutilated, is detached from the church by the shortening of the western part of the nave."

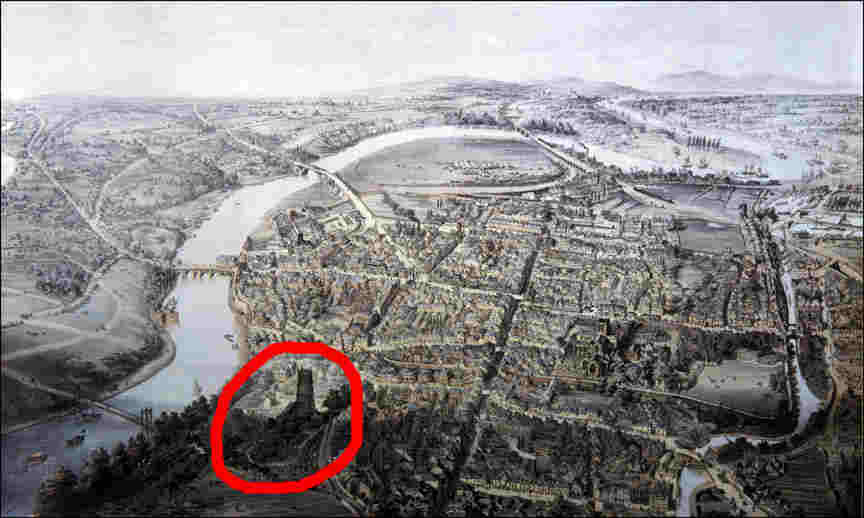

St Johns is shown very clearly in the John McGahey "balloon" view of Chester from 1855. Close examination reveals that the tower is in a rather poor state of repair. In the 1870s further work was done in the churchyard, which was partly closed for burials in 1855 and completely in 1875. The project resulted in the excavation of the ruins and the removal of the houses built among them in the 18th century to disclose the vaulted undercroft east of the south transept. In 1875 the tower was described as "mouldering":

- “The ruins at the East-end, recently extricated from heaps of rubbish and the growth of trees, are now a recognised ornament of Chester, near the new park which is laid out on a table-land above the banks of the Dee; while the lofty tower, erect though mouldering, and still showing in parts some faint traces of its old enrichment, is conspicuous in every view of Chester, and rivals in its elevation the tower of the present Cathedral, which stands on the highest ground in the city.”

By 1860 it was clear that the tower was in need of attention:

- "the exterior of the church, in spite of its horrible mutilation, its decaying stone-work and barbarous modern repairs has a very remarkable, even stately, appearance, to which the grand and lofty tower, the picturesque ruins and the beautiful situation not a little contribute. The condition of the church was in every respect so bad that the inhabitants of Chester began some time ago to entertain the question of a restoration and laudable attempts were made to raise subscriptions to that purpose, but it was only within the last year that sufficient funds were obtained to justify actual operations. To effect the complete resoration of such a church would require a sum so large that the prospect of raising it may at once be considered hopeless... there is little chance of the repair of the fine tower, which is now in a very shattered and decayed state..."

Collapse!

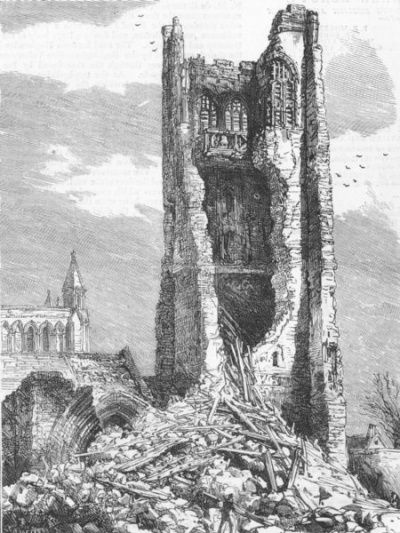

Given the clear and dire warnings that are repeated above it is not surprising what happened next: on Good Friday (15th April), 1881 the north-western tower collapsed.

Rev S. Cooper Scott recorded:

- "a rumbling noise, which was succeeded by a terribly and indescribably drawn out crash, or rather rattle, as though a troop of horse artillery was galloping over an iron road; this was mingled with a clash of bells, and when it had increased to a horrible and almost unbearable degree, it suddenly ceased, and was succeeded by perfect stillness"

Thomas Hughes, editor of the "Cheshire Sheaf" described it in the following detail:

“The night of the 14th and 15th of April, 1881, will be a melancholy one, and a memorable, in the history of the great Church of St. John's. On that night and a little after daybreak next morning, a calamity befel the church and the city, for which no amount of personal money sacrifice on the part of the citizens, or of their generous friends elsewhere, can ever adequately provide a remedy. The grand old Perpendicular Tower, and even more grand and graceful Early English Porch, have both in one night virtually become things of the past, for they lie today heaped together in one sad, solemn, undistinguishahle pile of ruin. Two sides only, it is true, of the steeple have as yet actually fallen; but it is almost morally certain that the two remaining ones, the southern and western faces, must one day follow the fate of the rest. Six or seven bells only, it was at first thought, out of the once melodious peal of eight, remain hanging, as it were almost literally, in mid-air: the other two, it was feared were in all probability lying shattered beneath the mass of fallen masonry- a wilderness of danger and desolation which will probably not be removable for some weeks to come. I was sitting alone in my room, and actually reading Ormerod’s description of St. John’s, at the very instant, 10 o'clock, when the crash of masonry, mingled with the sound of tinkling bells, fell upon my ear! The conviction at once seized me that the great Tower had succumbed; for the imminence of its fall had been for some days past manifest to all who, like myself, had watched the widening cracks in the eastern and northern faces of the structure. I was on the spot in a few moments, and realized at once all my worst fears ; for there, palpable in the moonlight to every eye, ran a fearful chasm up the northern wall of the steeple; the belfry being exposed, but the bells still all, as it now turns out, standing, though awaiting as it then seemed to every one, an all but certain destiny ere a few hours should pass by! It was a sight to daze the head, and well nigh disorder the brain, of one who reverences and revels in the treasures of the past! Exactly three centuries ago this very year, viz., in 1581, the parishioners, having their old church, with the western end in ruins, through the fall seven years previously of the eastern and southern sides of the tower, handed over to them by Queen Elizabeth, began at great cost and labour to close up again the stunted nave. Apparently also, at least two other extremities of the cruciform church were reduced and closed in at the same date, and divine service was thenceforward celebrated, on the Reformed basis, in the still handsome parish church. The steeple, too, was rebuilt as far as needful at the same period: and the work our zealous forefathers then bequeathed us has borne the wear and tear of three hundred years gallantly, till hard fate has re-enacted, now, the fearful havoc the previous fall did for the sacred fabric in 1574! But it has done more than this; for that one night's wreck has deprived us of the chaste and beautiful Early English Porch, which had become, as time grew on more precious and beautiful still after its nearly three centuries' accumulation of mould and decay. There it lies now, crushed and mangled beyond, it is sadly to be feared, the possibility of restoration; and thus has one more milestone, marking the city's life journey, perished before our very eyes! The fragment remaining of the steeple, for a second fall occurred at four next morning, is probably doomed to immediate destruction. If so, old Chester will be shorn of another grand feature in its sky-line for, viewed from whatever point the city may, the massive tower of St. John's has been long a landmark familiar to the eye and dear to the sympathies of the thoughtful Cestrian, and to every intelligent visitor to our venerable city”.

Restoration

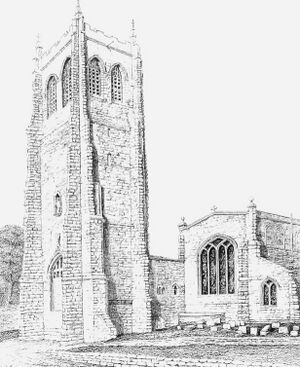

The collapse destroyed the north porch, which was rebuilt in 1881–82 by John Douglas. The statue sometimes said to be of king Ethelred on the reconstructed porch originally decorated the Central Tower, being found "miraculously unhurt" amonst the rubble when that tower fell, for the second time, in 1572. The statue was transferred to the West Tower, from whose ruins it was once again rescued in 1881. There is some slight doubt as to whether the statue, which appears to show a man with a hind, is actually meant to be Ethelred, as the symbolism would also fit St Giles. The rather dull Victorian appearance of the exterior of present day St. John's is the result of the "restoration" carried out by Richard Charles Hussey: Hussey rebuilt the south side in 1859-60 and the north in 1886-87, and the addition of John Douglas's clock tower in 1887. The external appearance of the church today is of a 19thc. building in Early English style

In 1925 the chapel at the south east corner, then the Warburton chapel, was extended and refurbished by Sir Charles Nicholson to form a Lady Chapel with a new screen and a reredos reconstructed from that of 1692. The monuments include three mutilated 14th century effigies, that of Agnes of Ridley (d. 1347) being half-length with the lower part of the body enclosed in a coffin carved with vine leaves. Notable tombs in the south-east chapel are those of Lady (Diana) Warburton (d. 1693) and Cecil Warburton (d. 1729). At the west end armorial fragments survive from the tomb of Alexander Cotes, erected in 1602 and destroyed in the Interregnum. There are also several monuments on panels, painted by the various Randle Holme's between 1628 and 1682.

The Coffin in the Wall