Brown

Sir Thomas Browne (19 October 1605 – 19 October 1682) was an English polymath and author of varied works which reveal his wide learning in diverse fields including science and medicine, religion and the esoteric. His father was a silk mercer from Upton. Sir Thomas is largely forgotten in Chester, where a family with a similar name are much better known for their department store "Browns of Chester" (often once called "The Harrods of the North"). However, a large bronze of him (by Henry Alfred Pegram) is to be found in Norwich city center and his writings have been the subject of vast scholarship.

Sir Thomas' writings display a deep curiosity towards the natural world, influenced by the scientific revolution of Baconian enquiry. Browne's literary works are permeated by references to Classical and Biblical sources as well as the idiosyncrasies of his own personality. Although often described as suffused with melancholia, his writings are also characterised by wit and subtle humour, while his literary style is varied, according to genre, resulting in a rich, unique prose which ranges from rough notebook observations to polished Baroque eloquence. Sir Thomas is cited as the first to use many words in common usage today, and it is generally believed that these words were ones that he himself coined from his vast classical knowledge. Somewhat surprisingly, these words include: "computer" and "electricity". In the 18th century, Samuel Johnson, who shared Browne's love of the Latinate, wrote a brief Life in which he praised Browne as a faithful Christian and assessed his prose thus:

- "His style is, indeed, a tissue of many languages; a mixture of heterogeneous words, brought together from distant regions, with terms originally appropriated to one art, and drawn by violence into the service of another. He must, however, be confessed to have augmented our philosophical diction; and, in defence of his uncommon words and expressions, we must consider, that he had uncommon sentiments, and was not content to express, in many words, that idea for which any language could supply a single term"

Sir Thomas Browne is not a direct ancestor of the Browns who opened their noted store in Chester - the last common ancestors with the Brownes of Upton (and later Hoole) are his grandparents. While a look at his ancestry reveals that there were significant connections between the Brownes of Upton and the London fashion trade long before the store opened its doors. It also shows how the male line of the Brownes from the Upton gentry almost died-out on the Chester side, and failed completely for the descendants of Sir Thomas. A little further investigation reveals that the Browns of "Brown's of Chester" are unrelated to the two branches of the Brown(e)s in Chester (Netherlegh and Upton) and therefore unrelated to Sir Thomas Browne, despite what some "city guides" may be heard saying to tourists.

In summary there are at least three distinct sets of Browns:

- The "Browns of Chester" (Department Store) Browns, who came from Lancashire;

- The Brownes of Netherlegh - wherever Netherlegh was, and;

- The Brownes of Upton (of whom a branch gave rise to the noted polymath Sir Thomas Browne);

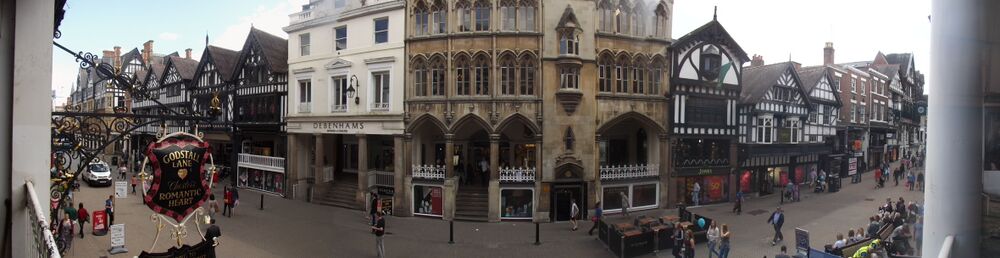

"Brown's of Chester"

Number #32-34 is a Greek Revival building from 1828 which was the first element of what was to become Browns Department Store (N.B. Wikipedia states the oldest part of the store dates from 1858). Following the Commercial News Rooms (1807-8, which also involved a Brown), this second neo-classical building was the first purpose built store in the City.

William Brown was a successful druggist and was married to Susannah Towsey, an ambitious milliner, and they began to import the latest fashions from London. Susannah (who was christened at St Peters in 1758) ran a little drapery and haberdashery shop (in existence by 1781) with her sister, Elizabeth, at the corner by the Cross. The sisters were the daughters of Thomas Towsey, a feltmaker (made Freeman 1745, and himself the son of another feltmaker: John Towsey), and sisters to John a hatter and hosier who kept a shop in Northgate Street (he was declared bankrupt in 1790 and died soon afterwards, with his widow carrying on the business). Her family had been connected with the hattery and hosiery business in Chester from the early 1700's. In the 1780's Susannah and Elizabeth would take the stage coach down to London twice a year to select the new season's fashions from the City wholesalers. On returning to Chester they would place an advert in the local mewspaper inviting the public to come and view their collection.

Susannah married John Brown, who had his druggist's shop a few yards down the street, in 1788. His family had a background in shoe-making. Children of John & Susannah included William Brown b. 10th Apr 1789 and Henry Brown b. 25th Jul 1795. Pigot's Directory of Cheshire 1828-29 lists 'Brown Wm & Hy Milliners Eastgate Street Row Chester'. The plans for the new shop were laid before the Assembly in 1828 and it was built by 1831. Browns directly employed 150 women in their own dressmaking workroom in the 1870s.

Brown’s of Chester not only drew a wealthy clientele from amongst the gentry and middle classes of rural Cheshire, but also from the prosperous suburbs of the Wirral: well within the apparent hinterland of Liverpool stores. The attraction was partly Brown’s upmarket image and partly the quintessential "Englishness" of the city. As one customer put it:

- "the ladies of the household of what were known as the Merchant Princes of Liverpool would prefer a shopping day involving a run in the car through the Wirral to the always ancient and interesting city of Chester, rather than to the ferry crossing of the River Mersey"

The "Mass Observation" study of Brown’s of Chester in the 1940s found that one floorwalker was willing to accept the "best artisan type", but hoped that "we’ll never go down to the lowest". The restaurant manager was even less certain, worried about the tendency for working-class people to "eat with their knives". Some customers were also worried about a potential move down-market, one complaining that "nowadays, you meet the people from the back streets there"; but others still saw it as exclusive, maintainingthat "I never go to Browns, I leave that to the toffs".

Mass Observation recorded that 60 percent of Brown’s customers were from the artisan class and 11 percent from the unskilled working class; the report also observed that "women from socio-economic class C now wander about as if they own the place". "NRS social grade" C, developed in the 40's and 50's consists of those whose head of household work in supervisory or clerical and junior managerial roles, administrative or professional or are skilled manual workers.

Brown and Son, silversmiths

Half-way from Brown's store to the High Cross is a shop doorway marked (on the step at Row level) as "Brown's Jewelers". The firm of G.J.H. Brown and Son Ltd., originally known as Brown Brothers, was established in 1859. In Morris and Company's, Commercial Directory and Gazetteer of Cheshire, 1864, the business is described as 'Brown Brothers, watchmakers, gold and silversmiths, jewellers and opticians, 3 Bridge Street Row'. The address is given as 5 and 7 Bridge Street Row in Morris and Company's, Directory and Gazetteer of Cheshire with Stalybridge, 1874, and by 1878, the business had moved to premises at 2 Eastgate Row South (See Phillipson and Golder's Directory for Chester, 1878-79, p. 43). George John Hemsley Brown, from whom the firm took its name, is listed in Morris's Directory, 1874, as a 'china, glass and earthenware dealer' of 63 Bridge Street Row, and in Phillipson and Golder's Directory, 1878-79, as a 'glass and china dealer'. However in Slater's, Post Office Directory of the City of Chester, 1882, he is listed as a 'watchmaker' of Brown Brothers, residing at 18 St. Martin in the Fields. By the 1890s, the firm appears in local Directories as G.J.H. Brown and Son.

Browns of Chester (Hoole)

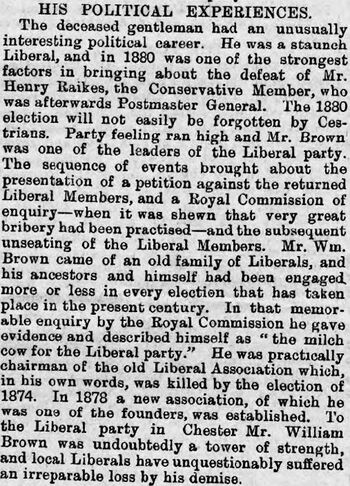

The Chester Courant and Advertiser (14th March 1900) gives the following information as to the ancestry of the "department store" Browns, triggered by the death of William Brown (links added for background):

- The Browns who became "Browns of Chester" were in the seventeenth century a yeoman family hailing from Ribbleton, in Lancashire. In 1676 William Brown, an ancestor of deceased, resided at Cattford, near Woodplumpton. To him was born in Feb. of that year his eldest son, William, who was baptised at Catford, and was thrice married, but had no issue by either his first or second wife. He married for his first wife Catherine Latham, daughter and eventually sole heiress of Capt. Richard Latham, of Parbald Hall and Allerton, co. Lancaster, by Catherine Massey, his wife, one of the eleven children of Sir Wm. Massey, of Puddington, co. Chester, who was knighted at Chester by King James the First on Aug. 23rd, 1617. William Brown (or Browne, for prior to the Civil War the name was spelt with a final "e" settled with his young Lancashire wife in Chester, where in Barn-lane (now King Street) several children were born to him prior to the accession of George I. (1714), and where he died in 1720, being buried at St. Oswald's, Chester, on June 13th of that year. His eldest son, William Brown became an Alderman of the Cordwainers' Company at Chester, having been sworn a freeman of the city and of that guild in 1733. He served the office of churchwarden of St. Oswald's in 1753, having married at that church on January 20th, 1730, Ann, daughter of Mr. John Golborne, second master or usher of the King's School, Chester. There were six children of this marriage, Christopher and Henry Brown being two of them. The eldest son, William Brown, born in 1733, married at St. Peter's Miss Katherine Meredith, and had issue—four sons and two daughters, of whom John Brown, the eldest son, was a druggist, born in Pepper-street in 1756. He married Susannah, daughter of Thomas Towsey, of St. Peter's, and, dying in 1810, was succeeded (with other issue), by his eldest son, William Brown, Mayor of Chester in 1841 and J.P., who died unmarried on June 13th, 1852. It was he, by the way, who founded the old Mechanics' Institution of this city. His third brother, Henry Brown, also died unmarried at Chester in the year of his mayoralty on August 6th, 1853, and was buried in the new cemetery. Their second brother, John Brown, born in 1792, continued the line, having married Ann, daughter of William Monk, collector of H.M. custom at Parkgate, and, dying in 1846, was buried at St. John's, having had issue four sons and four daughters. Of these latter the eldest is Miss Nessie Brown, of Richmond Bank, Boughton, while of the former Mr. William Brown, who has just died, born at Flookersbrook on May 31st, 1816, was the eldest son, and Mr. Charles Brown, Folly House, Flookersbrook, sheriff of Chester city in 1875, mayor in 1880 and 81 and again in 1884 and 85, is the second son. The deceased married at the Collegiate Church (now the Cathedral), Manchester, on December 10th, 1846, Emma, daughter of Charles Travis Faulkner, of Newton Grange, Manchester.

As a postscript to the above, Charles Brown was to survive his brother by only a few weeks, dying himself in April 1900. Despite the overheard comments of some Chester city guides, these Browns are not relatives of the Brownes who were silk-merchants in Chester and London and therefore unrelated to the Sir Thomas Browne who gave us the words "computer" and "electricity", despite the latter's connection with Chester.

It should perhaps be noted that Capt Richard Lathom's daughter, Catherine Latham, may not have become his "sole heir", but that is off-topic.

Brown of Chester Ancestry (partial)

From the above, in places rather confusing newspaper report, and some wills asreported in the newspapers, it is possible to reconstruct the family of the "Browns of Chester" as follows (although the more recent Browns require further research):

- William (of Catford, Woodplumpton)

- *William Brown (b.1676 - d.1720) = (3) Catherine Latham (b. 1659) - daughter of Richard Latham (b. 1621 - d. after 1658/9)

- *William (b.1703 - d. 1771: Shoemaker, alderman 1733) = Anne Golborne

- *William (b. 1733 - d. 1819: Shoemaker) = Katherine Meredith

- *John (b. 1756 - d. 1810: Druggist) = Susannah Towsey (b. 1758 - founded "Browns of Chester")

- *William (b. 1789 - d. 1852, Draper, no issue) - ran store

- *Henry (b. 1795 - d. 1853, Draper, no issue) - ran store

- *Sarah (b. 1790)

- *Eliza (b. 1794)

- *John (b. 1792 - d. 1846: Auctioneer) = Ann Monk (of Neston)

- *William (of Hoole b. 1816 - d. 1900: Mercer) - ran store = Emma Faulkner

- *Helena

- *Louis (b. 1848)

- *Francis (b. 1851 - d. 1907) - ran store - profession listed as "cabinet maker"

- *Henry (Harry) (b. 1857 - d. 1936) - ran store = Louise Phyllis Humphrey (donated Earls Eye to Chester)

- *Stephen (b. 1906)

- *Francis (b. 1912)

- *Ernest =

- *Lucy Elizabeth = Rev Charles Griffin

- *Daniel

- *Charles (of Hoole, b. 1818 - d. 1900: Mercer, no issue) - ran store

- *Nessie (b. 1814 - d. 1905 - no issue)

- *John = Mary

- *William (of Hoole b. 1816 - d. 1900: Mercer) - ran store = Emma Faulkner

- *John (b. 1756 - d. 1810: Druggist) = Susannah Towsey (b. 1758 - founded "Browns of Chester")

- *Christopher

- *Henry

- *Thomas (watchmaker)

- *William (b. 1733 - d. 1819: Shoemaker) = Katherine Meredith

- *William (b.1703 - d. 1771: Shoemaker, alderman 1733) = Anne Golborne

N.B. Further research appears needed here as there appears to be some confusion around the Browns in the early 18th Cent. There was also in Chester a Henry Thomas Brown (Mayor 1899-1900, Alderman and solicitor), Colonel in the Volenteers, son of W H Brown (solicitor), only son of H. T. Brown (London banker), himself the younger son of W H Brown a Buckinghamshire landowner who retired to Chester. This Brown has a younger brother George who lived in Tasmania.

Nessie Brown paid for the erection of the memorial obelisk at Boughton and it bears the words "Erected by Nessie Brown 1898".

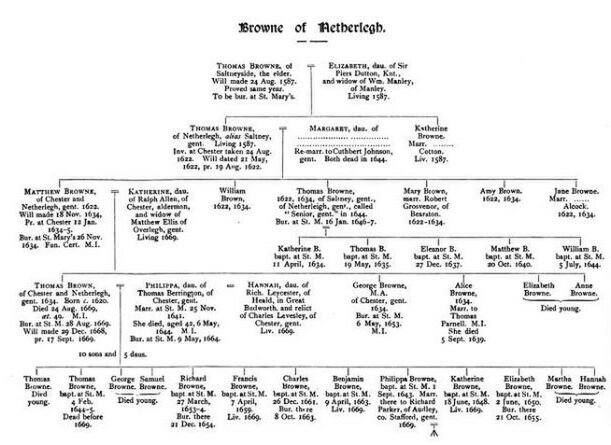

Browne of Netherlegh

There was a separate branch of the Brownes south of the River Dee in Netherleigh/Netherlegh and their story leads on to that of the relocation of the High Cross to Netherleigh (see: Cowper) after the Civil War. The Victoria History gives the following information:

- "The ancient mansion of Netherleigh Hall on its moated site passed with another part of the estate to the Browne family of Upton (sic), who resided there in the 17th and 18th centuries until they sold it to John Bennett of Chester in 1774. The hall, which had been fortified by Sir William Brereton in 1645 for use as his headquarters during the siege of Chester, was eventually let to tenants, and in the early 19th century was occupied by a farmer. It afterwards disappeared and at the time of writing its site was unknown."

In 1735 a part of the original estate was sold to the Chester alderman John Cotgreave. Thereafter the Cotgreave family built a modest seat, known as Netherleigh House, on the west side of Eaton Road. A late Georgian two-storeyed brick building of c. 1813 with two shallow bows to the front and a three-storeyed mid 19th-century addition to the rear, it was purchased by the 1st duke of Westminster in 1878. This building remains, but it is not at all clear that it stands on the site of the "Netherlegh" home of the Browne's of Netherlegh. Examination of whether it has the remains of a moat might shed further light on this: LIDAR shows some rectilinear features.

An example of one member of this branch is given below:

Mathew Browne (d. 1634)

According to Earwaker his funeral certificate reads:

- "Mathew Browne of the City of Chester, gentleman, dyed at his house in Handbridge vpon the .. daye of .. 1634 and was interred in St Maryes Church in Chester aforsayd. He married Katherine, daughter to Rafe Allen of the City of Chester, Alderman and widow of Mathew Ellis of Overleigh, nere Chester, gent and by him hay yssue Thomas, his sonne and heyre of the age of 14 years or thereabout at tyme of his fathers death, George 2nd sonne; Alice the only daughter. He has yssue also by her Elizabeth and Anne and a son not baptised which all dyed younge."

Mathew Ellis, as mentioned above, is interred at St Mary on the Hill where Hanshall and Hemingway both record his memorial tablet (Hemmingway locates it "in the Overleigh Pew", south aisle) as reading:

- "Here lies interred Matthew Ellis of Overleigh in the county the city of Chester, one of the gentlemen of the body guard to Henry VIII son of Ellis ap Dio ap Gryffyth successor to Kenrick Sais a British Nobleman and lineally descended from Tudor Trevor of Hereford. He died April 20 1574. Alice his wife died lö47. His son Matthew Ellis of Overleigh gent died 1575 whose Eliz daughter of Thos. Browne of Netherlegh gent died 1570 having issue Julian who was married to Thos Cowper of Chester Esq. Margery and Matthew Ellis of Overlegh gent. He died July 13 1613. His wife daughter to Richard Birkenhead of Maule Esq died July 6 1640 having issue Katherine wife to Randle Holme Chester gent & Matthew Ellis of Overlegh gent who died Nov 2 1663 his wife Elizabeth daughter to Wm Halton of Baddiley gent married Anne daughter to John Birkenhead of Backford Esq. He died Feb 17 1685; she died Aug 4 1689. Beati sunt mortui qui in Domino moriuntur. ". The latin reads "Blessed are those who die in the Lord".

From the above it can be seen that the Brownes of Netherlegh were a well-connected Chester family, however the historical record turns up little of interest in their conduct other than a possible connection to the various relocations of some or all of Chester's High Cross. The male line appears to die out in the 1660's.

Many of the memorials at St Mary on the Hill are only known to us from the writings of such as Hanshall and Hemingway, as repeated by Earwaker. Hemingway writes:

- "It does not appear from any thing I have been able to collect when these reliques of antiquity and superstition were destroyed; but it is probable their demolition may be ascribed to puritanical zeal, when the parliamentary forces had possession of the city about 1647."

Hemingways explanation for the destruction of the monuments does not fit the facts: he describes memorials with dates in the 1690's, well after the Restoration of 1660. As Hemingway was writing long after the Civil War he must have had an earlier source. This Hemingway cites as William Smith and William Webb in the "Vale Royal".

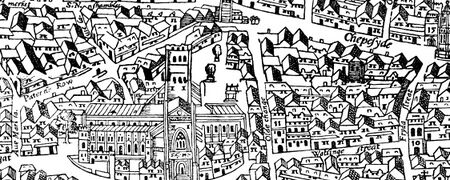

William Smith (d. 1618), herald, born about 1550 at Warmingham in Cheshire, was a younger son of Randle Smith of Oldhaugh in Warmingham, by his wife Jane, daughter of Ralph Bostock of Norcroft in Cheshire. About 1575 Smith became a citizen of London and a member of the Haberdashers' Company. He emigated to Germany about 1578, and for some years kept an inn at Nürnberg with the sign of the Goose. On the death of his father, on 6 Oct. 1584, he returned to England, and in 1585 took up his residence in Cheshire. On 23 Oct. 1597 he was created "rouge dragon pursuivant" on the recommendation of Sir George Carey, knight marshal. He never attained higher office, owing partly to a lack of amiability and a sharp tongue. He died on 10 Oct. 1618. Smith is noted for the Smith Map of Chester.

Webb appears to have written the bulk of "King’s Vale Royal" around 1622 - apparently inspired by John Speed (Speed was born at Farndon and died in 1629). Much of Webb's text appears to be derived from the works of Sampson Erdeswick (1590s), and other gentlemen antiquaries such as Ralph Starkey and John Booth. In Cheshire the genealogical works of locally-based antiquaries were also gleaned from a range of family and earlier monastic manuscript collections. These were in turn utilized by heralds such as Robert Glover and William Flower. Many of these works need to be treated with caution, not only because of accumulated ettors, but also due to the fact that Elizabethan courtiers were not beyond outright fakery to give them a pedigree which would improve their reputation and advance their prospects. However Hemingway's reference to Smith and Webb does not make much sense either as both Smith and Webb were dead by some of the dates inscibed on memorials they supposedly described.

Browne and the High Cross

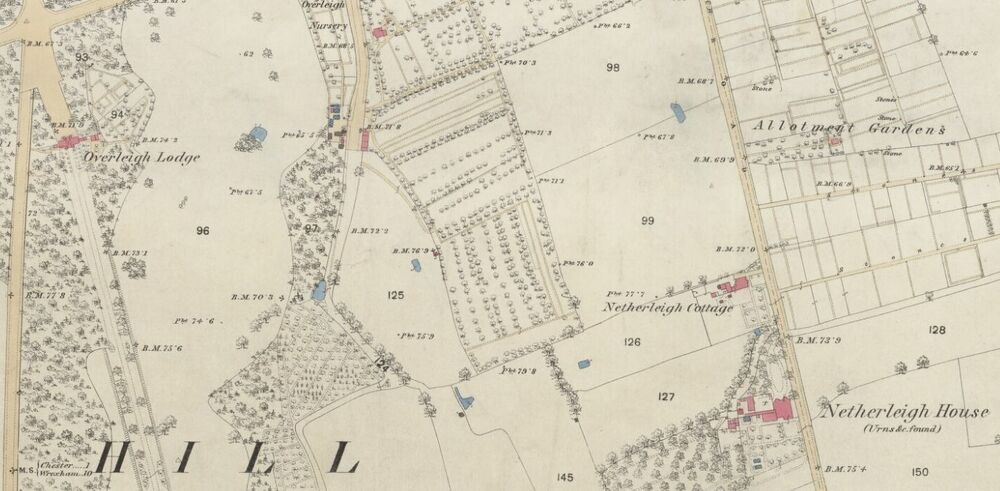

"Netherlegh House" is marked on the 1874 OS map as shown below.

The other relevant maps and photographs for this section are given in the gallery below.

The articles of the surrender of Chester in the Civil War, agreed on 31 January and 1 February 1646, included the following terms: the officers and a few soldiers were allowed to march out with arms and limited amounts of money; other soldiers were to leave their arms and horses behind; the governor and others were allowed to march to Conwy without hindrance; Welsh soldiers were permitted to go home, but those of Irish parentage were to be prisoners; the persons and goods of citizens were to be protected; no churches were to be damaged; imprisoned parliamentarians were to be released; and the city and castle were to be delivered to Brereton. Broster gives the text of the surrender agreement, which contains the provision:

- "That no church within the city or evidence or writings belonging to the same shall be defaced"

Despite the assurances given, the parliamentarians smashed up the cross, although technically it was not part of a church.

A "True Cross" Gallery

-

Extract from the Lavaux Map - this shows Overleigh, Brown's Lane and the valley

-

1874 OS Map, showing the "Manor House" off Brown's Lane

-

Netherlegh House in 2019 - the grounds have not been examined for a moat

-

Extract from the 1839 "Tithe Map" of Chester

-

Extract from an 1825 Map - with the line of the Grosvenor Bridge as originally planned

-

Satellite image of "The Manor House" - the grounds have not been examined for a moat

-

Walking group in the valley mapped by Lavaux. The bridge shows the depth of the valley

-

The cross in 2019 with (Japanese) tourists for scale

The High Cross was supposedly "hidden under the steps of nearby St Peter's Church, and stayed there forgotten until it was rediscovered in 1820, during the course of repairs." We are then told that "a churchwarden placed the pieces in his garden in Handbridge, until they were acquired by the 1st Duke of Westminister some 60 years later" (who apparently gifted them to the Grosvenor Museum). The city council re-erected the Cross in the Roman Garden in 1949, but, with the coming of pedestrianization, it was restored to its ancient original site at the intersection of the city's main streets in 1975, after an absence of some 329 years.

As regards the temporary location of the High Cross "in Handbridge" we can consider the following:

- The male line of the Brownes of Netherlegh failed in the second half of the 17th Century, with only female Brownes (possibly even only one) having children. However the property was only sold out of the family in 1774 (to John Bennett) according to the Victoria History (they cite P. J. W. Higson, 'Landlord Control and Motivation in the Parl. Enclosure of St. Mary's-on-the-Hill Parish, Chester', T.H.S.L.C. cxxxvii. 95, 111; Hemingway, Hist. Chester, ii. 230–1; Eaton Hall, Chester Estate Deeds, Box X, no. 4). Netherlegh was apparently still a house let to tenants until it became a farm "in the early 19th Century";

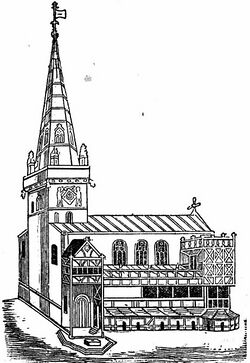

- The sketch of Overleigh Hall reproduced above shows what could be the High Cross and shows a building in the background which could be Netherlegh, which is known to border on Overleigh. The sketch is taken from: Journal of the Architectural, Archæological, and Historic Society, for the County, City, and Neighbourhood of Chester, Volume 1 (1849-1855). According to the Journal, the "sketch is from a small water colour drawing in the possession of Mr T Topham". A Thomas Topham, who joined the CAAHS in 1850, lived in Castle Street;

- Using the Lavaux Map it is possible to georeference the position of Overleigh Hall on modern maps. The location falls near the roundabout at the southern end of the approach road to the Grosvenor Bridge. There is no "Netherlegh" on the Lavaux Map. Prior to the construction of the Grosvenor Bridge (see the Lavaux Map) there was a distinct geographical feature, in the form of a narrow but deep valley running down to the River Dee hereabouts (which can still be seen today - the footbridge crossing it gives an impression of its depthj). This valley possibly ran between two places with the pre-fixes Nether- and Over-. "Leigh" or "Legh" is associated with a forest clearing;

- Looking in the direction implied by the layout of the buildings in the sketch and their orientation on the Lauvaux Map, the possible Netherlegh shown in the sketch would be in the region of what is, to the present day, is still called "Brown's Lane" and, indeed, marked as such on the Lavaux Map. Near Brown's Lane is a property known on older maps simply as "The Manor House", although is is now called "Overleigh Manor". This is not an early building, but it may be named because an actual manor house stood or or near its site. The tithe maps for Chester (around 1842) show that buildings in Brown's Lane (which is marked as such on the tithe maps) were owned by the Bennett family (who purchased Netherlegh from the Brownes);

- Overleigh and nearby land were being "enclosed" (for the benefit of the Duke of Westminster around 1805. If the High Cross fragments were found at St Peter's in 1820, then "some 60 years later" brings us to around 1880, so the relevant Duke of Westminster would be Hugh Lupus Grosvenor (d. 1899). At the time he either dealing with or just about to deal with the potential scandal over the racehorse "Bend Or", and, dealing with the fall-out from a rigged election (or just coming-up to one).

- According to "Building Chester" (Philip Jones) the remains of the High Cross were rediscovered in 1804 and stored at St Peter before being handed over to Sir John Cotgreave (d. 1836) in 1815, who relocated them to "his new home at "Netherleigh" in the suburb of Handbridge". As noted above the Cotgreave family built a modest seat, known as Netherleigh House, on the west side of Eaton Road around 1813. This can be located on old maps, such as the one given above (where it can be seen that remains, presumably Roman, have been found on the site);

- "Historic England's" entry for Netherleigh House reads: "Small country house. c1800 extended to rear probably mid C19. Brown brick, Flemish bond to front; grey slate roofs. Front wing 2 storeys of 5 windows to front; 3-storey rear wing. Painted stone plinth; portico, 2 front columns and 2 half-columns behind; door of 8 fielded panels; columns and entablature of Roman Doric derivation, with fluted capitals. A shallow 2-storey brick bow to each side of entrance; recessed sashes of 12 panes to ground floor and 15 panes to first floor, 2 on each bow to each floor and one over entrance; painted stone sills and wedge lintels; 2 cast-iron rainwater pipes and heads; parapet with full moulded cornice; 2 brick chimneys. The rear wing with hipped roof at right-angle to front has 4-pane recessed sashes".

- Burke's Peerage (1833) gives the following information on the Cotgreaves: "Estates: Netherlegh. This estate belonged to the Barons of Halton and granted in trust to Herbert d'Orreby by Geoffrey de Dutton about 1270 when he assumed the cross and embarked in Crusade. It was afterwards held under the Warburtons by the Orrebys of Gawesworth and passed by marriage with an heiress the Fittons, from whom it came to the Stanleys of Alderley, who sold it in 1735, to John Cotgreave esq. The ancient mansion is within a moated site and is occupied as a farm house. During the siege of Chester in 1645 it was fortified by the parliamentary general Sir William Brereton who fixed his head-quarters there. Another portion of Netherlegh was purchased in 1756 by John Cotgreave from the Lakes, of Edmonton, in the county of Middlesex. Property in Overlegh: all within liberties of the city of Chester.. ..Lands in Handbridge and in the of the city of Chester purchased by Cotgreaves in the years 1435, 1512, 1691, 1726 and 1736. Seats: Netherlegh House standing the right hand side of the road leading to Eaton a short distance from Handbridge." The ownership history in Burke does not mention the Brownes at all.

- Hemingway (c. 1826) appears to confirm much of the last paragraph, as he writes of Netherleigh:

- "At a short distance on the road to Eaton, on the right hand side, stands Netherlegh House, the residence and property of Sir John Cotgreave.. ..The ancient mansion is within a moated site, and is now occupied as a farm house. During the siege of Chester in 1645, this house was fortified by the parliamentary general, Sir William Brereton, who fixed his head-quarters there.".

This agrees with "moat" and "Brereton";

Hughes (1858 - page 50) writes:

- "Some fragments of the Cross were picked up at the time and hidden within the porch of St Peter's Church hard by where a century or so afterwards they were discovered and now ornament the grounds of Netherlegh House near this city."

Hughes is usually accurate as regards contemporaneous facts, so it can be safely assumed that the High Cross was in fact located in the grounds of Netherlegh House on Eaton Road. However, that does leave two "loose ends": did the Brownes of Netherlegh live on the site of Netherlegh House? (or near "Brown's Lane") - and - is the High Cross really shown in the sketch of Overleigh prepared for the CAAHS sometime before 1830? Also, note that Hughes is way out on the "discovery" date - his "a century or so afterwards" would place rediscovery of the "fragments" in the 1740's.

Broster (1800: History of the siege of Chester) gives an exact date for the destruction of the Cross in 1646:

- "Feb 16: At the same time the sword and mace were restored to the city the high cross pulled down and the fonts taken away out of the parish churches in Chester."

There are some clear contradictions in the above:

- DATE OF REDISCOVERY?: Jones gives 1804, while other sources give 1820;

- WHO MOVED IT?: Some sources state "a churchwarden" others (including Jones) state "Sir John Cotgreave";

- WHERE DID THE BROWNE'S LIVE?: Some evidence suggests near "Brown's Lane", other evidence suggests at the later site of ("moated") Netherlegh House;

where they lived..

Today, Netherliegh is a Georgian country house on Eaton Road, half-hidden behind high hedges. Labels on the older OS maps shows that Roman remains have been found there. Eaton Road follows the line of the Roman road leading to Heronbridge and then on to Viroconium (Wroxeter). Hemingway and others write that the site was once moated and that it played a part in the Civil War:

- "At a short distance on the road to Eaton, on the right hand side, stands Netherlegh House, the residence and property of Sir John Cotgreave.. ..The ancient mansion is within a moated site, and is now occupied as a farm house. During the siege of Chester in 1645, this house was fortified by the parliamentary general, Sir William Brereton, who fixed his head-quarters there."

This implies the existence of a much older house than the Georgian building now on the site. The question is whether the "Browne's of Netherlegh" lived there or elsewhere. Turning to the list of owners given in Burke, the Browne's are absent from the list:

- "Estates: Netherlegh. This estate belonged to the Barons of Halton and granted in trust to Herbert d'Orreby by Geoffrey de Dutton about 1270 when he assumed the cross and embarked in Crusade. It was afterwards held under the Warburtons by the Orrebys of Gawesworth and passed by marriage with an heiress the Fittons, from whom it came to the Stanleys of Alderley, who sold it in 1735, to John Cotgreave esq. The ancient mansion is within a moated site and is occupied as a farm house. During the siege of Chester in 1645 it was fortified by the parliamentary general Sir William Brereton who fixed his head-quarters there. Another portion of Netherlegh was purchased in 1756 by John Cotgreave from the Lakes, of Edmonton, in the county of Middlesex."

It should be noted that there are two different John Cotgreaves mentioned in the above. It is clear that the "Browne's of Netherlegh" are not recorded as living here. There is no mention of the sale of the Netherlegh ancestral home to John Bennet as recorded in 1774. Much the same is found in the Victoria County History:

- "Netherleigh. Occupying an area directly south of Handbridge beside the river and on the road to Eccleston, Arni's estate, assessed at 1 virgate, had been granted by 1086 to William fitz Niel. (fn. 53) The latter's eventual successor, John de Lacy, granted it to Adam of Dutton, from whom it passed c. 1270 to the Orby family of Gawsworth and thence in the early 14th century to the Fittons. Later, perhaps c. 1604, part of the estate was acquired by the Stanleys of Alderley, by whom it was sold in 1735 to the Chester alderman John Cotgreave. Thereafter the Cotgreave family built a modest seat, Netherleigh House, on the west side of Eaton Road. A late Georgian two-storeyed brick building of c. 1813 with two shallow bows to the front and a three-storeyed mid 19th-century addition to the rear, it was purchased by the 1st duke of Westminster in 1878."

One alternative home for the Browne's might be found in the area of "Brown's Lane". This is marked on the Lavaux Map as such and still has the same name today. The area around Browns Lane is separated from Overleigh by a shallow valley (shown on the Lavaux Map and photographed above) which still survives in part today. The valley is steep enough to require an iron footbridge for passage across it. This valley possibly ran between two places with the pre-fixes Nether- and Over-. "Leigh" or "Legh" is associated with a forest clearing. At the date of the tithe maps (1839), the Bennetts, who had purchased Netherlegh (1774) still owned a row of cottages on the south side of Brown's Lane. Late Victorian maps of the area show a building marked as "The Manor House", but no sign of a most. Today the building on "Manor House" site is called "Overliegh Manor" and appears of early Victorian construction - it is not known whether there was an earlier building on the site. All of this conflicts with what is also written in the Victoria County History:

- "The ancient mansion of Netherleigh Hall on its moated site passed with another part of the estate to the Browne family of Upton (sic), who resided there in the 17th and 18th centuries until they sold it to John Bennett of Chester in 1774. The hall, which had been fortified by Sir William Brereton in 1645 for use as his headquarters during the siege of Chester, was eventually let to tenants, and in the early 19th century was occupied by a farmer. It afterwards disappeared and at the time of writing its site was unknown."

The Victoria History mixes elements of "the moated hall occupied by Brereton" with the sale to Bennet, but then states that the whereabouts are unknown - i.e. that they are not known to be at Netherliegh House. It also repeats the statement about Brereton, which raises an issue over what exactly was occupied by the Parliamentarians. For an occupation, or even the location of a headquarters, to be so close to Chester implies an occupation late in the campaign leading to the close seige of Chester. For much of the campaign Chester had a land route open to Wales, as used by Charles both before and after the Battle of Rowton Heath. The Parliamenary forces occupied a ring around the east, north and west of Chester from their bridge of boats between Dee Lane and Queens Park, through Barrow and Picton to their emplacements at Brewer's Hall in what is now Westminster Park. At times the gap in this ring was held open by a "fort" in Handbridge, still commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Robinson in late September 1645. If the home of the Browne's was to the west of Handbridge it would be an excellent improvement on the Parliamentary position if they could capture it. There was certainly fighting nearby, as Overleigh was burnt down at around the time possibly as part of a co-ordinated advance through Upton and Mollington.

From the above, it is not clear whether the Brown's lived at what is now Netherliegh House (which seems unlikely) or whether their "ancient mansion" was elsewhere, possibly in the region of "Brown's Lane". There is hardly any historical evidence linking any Brown with Brown's Lane, except the following:

- "Later in the eighteenth century one finds, similarly, Kyffin Williams, Esq., 'His Majesty's Farmer of the Manor of Handbridge in the County of Chester and County of the City of Chester' in January 1750 leasing to one Matthew Brown, yeoman, a cottage, garden and field near Brown's Lane and a loond of ground at or near Low Hill in Handbridge, together with 'Privileges of Common Pasture upon Saltney to the said Premises belonging or Appertaining'." (G. of E. MSS., Box V, Bundle 1: ref in "POINTERS TOWARDS THE STRUCTURE OF AGRICULTURE IN HANDBRIDGE AND CLAVERTON PRIOR TO PARLIAMENTARY ENCLOSURE" P. J. W Higson)

In conclusion, the location of the ancestral manor of the Brownes seems hard to pin down. Netherlegh House is documented as being associated with the Cotgreaves and seems unlikely to have been occupied by the Netherlegh branch of the Brownes. There is a very tentative link to "The Manor House" in Brown's Lane: a lane which is marked as such in Lavaux and so probably got its name at an early date. However, there is no definitive conclusion to be drawn.

is it the High Cross ?

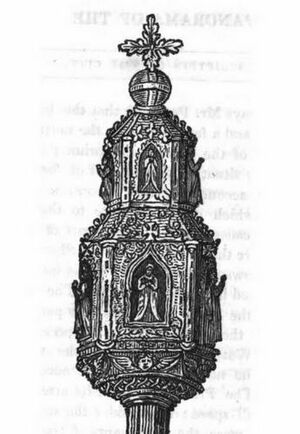

Today the High Cross sits outside of St Peter in the very center of Chester. The current reproduction has the appearance of a "Havdalah besamim tower" of which the shaft is modern, the "head" definitely old and the "cap" with its ball finial also of a relatively recent date. The translation of this particular cross can be seen in three parts: from St Peter's to "wherever", from "wherever" to the Grosvenor Museum, and from the Museum back to St Peter's. As regards when and "wherever", Frank Simpson states that:

- "At the time the steps of the church were reconstructed to face Eastward, certain portions of the cross were found, and placed inside the church, by the west door. They were seen to be there as late as 1815, but during the same year they were given by the churchwardens to John Cotgreave Esq of Netherleigh, Eaton Road, Chester, who had them placed in the grounds of his residence."

the evidence

Hemingway (who lived in Chester and was a local newspaper editor) writes as if he had actually seen the fragments of the cross at "beautiful" Netherlegh House, on Eaton Road. Hemingway's actual words are:

- "Within the walls the city as before observed is divided into four principal streets the centre of which is where the high cross formerly stood close to St Peter's church. The cross was erected in the time of James I and was pulled down and defaced by the Parliamentarians when they obtained possession of the city in 1646. The cross is delineated rudely in Randal Holmes's collections Harl MSS 2073 of which the following is a representation (refers to image). The upper portion of this remain of the olden times which surmounts the plain upright shaft is still preserved in the grounds of the beautiful villa of Sir John Cotgreave of Netherlegh near this city though some of the carved figures are a good deal defaced."

Hemingway is clear that the surviving bit of the cross is the decorated "head" and not the shaft or base. This is in complete contracdiction to what Hanshall wrote in his earlier "Guide to Chester" (this can be dated exactly: Cotgreave was mayor only once: 1815-16, and, was knighted during his mayoral year, 5 July 1816):

- "The socket of the Cross is now in the possession of John Cotgreave Esq the present worthy and public spirited Mayor of Chester. He intends erecting it in the garden of his beautiful villa on the Eaton road."

So, at first Hanshall says it is "the socket" and later. writing as if he had seen it with his own eyes, Hemingway states that it was the "upper portion..which surmounts the plain upright shaft". Hemingway even describes the "carved figures" shown in the illustration in Hanshall - which Hemingway also reproduces. The Hanshall image is based originally on a drawing by Randle Holme (Harl MSS 2073) - Holme could have actually seen the cross ouside St Peter. This desctiption fits roughly with the standard description of the cross:

- "The head of this original Cross was said to have been inscribed with ornate tabernacle work, along with images of various saints and been topped with a slightly smaller capital designed in a similar manner." (after Jones, and others)

According to local legend reported by Jones:

- "Sir John intended to use the shaft of the cross as the base for a sundial that was being installed within the grounds of his new home, but after being constructed it almost immediately fell down. Re-erected once again, the feature once again fell over and perhaps through utter disgust and personal frustration the stonework was simply allowed to remain in the ditch into which it fell."

This presents a third description - now it is the shaft which has survived and the mayor of Chester failing to be able to maintain an errection. Things get even more complicated: at Plas Newydd in Llangollen the garden hosts (click for photo) what is described by CADW as:

- "the base and part of the shaft of the C15 Chester High Cross which once stood in the centre of the city".

It is not known when and how this supposed fragment of the cross arrived at Plas Newydd (although Simpson gives a date of "about 1817"), but it looks like the sort of thing which would make a good base for a sundial. Holme appears to show the base of the cross, after the removal of the upper parts, in his illustration of St Peter. This is a square base and not the octagonal base of the reconstruction outside of St Peter.

The heritage listing for the High Cross as it has been reconstructed does not mention relocation at all and reads:

- "A medieval cross, 14th century in origin but now the greater part is modern. It consists of an hexagonal crown on three steps, plinth and shaft, all octagonal. The steps, plinth and shaft are modern; the crown is 14th century and the moulded shaft-base is probably medieval. The crown is badly weathered and capped by a more recent tapered finial surmounted by a ball. The cross was demolished probably after the surrender of Chester to the Parliamentarians in 1646, fragments discovered in the early 19th century were erected near the Newgate in 1949, all restored to the Cross in 1975."

The only thing that the various sources, including Hughes agree on is that some fragment(s) of the High Cross existed at Netherlegh House on Eaton Road in 1815-16. The most believable of the accounts is Hemingway who appears to be comparing what he has seen for himself with what he reproduces from Hanshall's own reproduction of Randle Holme. On this basis it would appear that it was at least part of the carved "head" of the cross which was at Netherlegh House.

the duke

The second part of the story of the translation of this cross ends with the cross fragment(s) arriving at the Grosvenor Museum around 1880, supposedly at the request of the Duke of Westminster. Frank Simpson writes:

- "At a later period, the late Duke of Westminster became owner of the property, and, at the request of the Chester Archaeological Society, ordered the removal of the upper portion of the ctoss to the Grosvenor Museum, for safe keeping and with a view to its re-errection in the City."

The Duke at the time would have been Hugh Lupus Grosvenor (d. 1899). 1880, if that was indeed the date of re-discovery, was a very busy year for him.

In the April 1880 Chester election the Grosvenors returned to politics after a short break, and, as was usual in Chester, the whole process was riddled with corruption - so much so that in July 1880 the MP's elected for Chester were unseated pending the outcome of an enquiry. According to local newspaper reports of the time the Grosvenors were involved in suspicious spending:

- "THE CHESTER ELECTION PETITION. The Chester Election Commission was resumed on Tuesday. Father Pacificus, head of the Catholic body ia Chester, said Mr Raikes called on him five months before the election, and urged that by supporting the Conservatives their schools would be free from secular teschings, but no pecuniary advantage to the schools was promised. He knew his men would vote for the Liberals, and hearing that his name was being used by the Couservatives, he issued a contradiction. Mr Salisbury, the Liberal agent, was examined at length as to the receipt of £1400 from Lord Richard Grosvenor as part of £2000 expended. On Thursday Mr Moss, the Liberal agent, was recalled at his own request. He gave an explanation as to a letter written by Mr Salisbury to Lord Richard Grosvenor, with reference to several sums of money. He said he was not present when tbe letter was written, and he knew nothing about the amounts until a month afterwards. He was unable to give any account of how a specific sum of £300 was expended in connectinn with the election, nor could be say why Mr Salisbury wanted a large sum of money in sovereigns. Tbe inquiry was again ajourned." (The North Wales Chronicle and Advertiser for the Principality: 26th February 1881)

The refernce to "Father Pacificus" may be a reference to a member of the Capichin Franciscans of Grosvenor Street: he died at Bruges, Belgium Nov.21 1888, but has a memorial in Chester. The "Mr Salisbury" mentioned above in connection with the £300 in sovereigns is the Chester ex-MP Enoch Salisbury. As well as having antiquarian interests, he was one of the key figures in running the local liberal party, another being William Brown (of the department store family), who was chairman and treasurer of the finance committee. Eventually the enquiry exonerated the candidates but imposed a seven-year disqualification from voting on 914 individuals who had given or received bribes or "treats", including William Brown.

The other dubious circumstances which embroiled the Duke in 1880 was the mysterious matter which probably formed the basis of the Sherlock Holmes story "The Adventure of Silver Blaze". In June 1880 the Epsom Derby was won by Grosvenor's horse "Bend Or" and "Robert the Devil" was placed second. However, a few weeks after the running of the Derby an objection was made by the owners of "Robert the Devil": "on the ground that Bend Or was not the horse he was represented to be, either in the entry or at the time of the race." A groom suggested that "Bend Or" (ridden to a win by the at times unstable Fred Archer) had been replaced by a disguised "Tadcaster" (also from the Eaton Stud). Bearing in mind that the groom, one Richard Arnull, had been fired by Westminster and was working out his notice when he made the allegation, it might have been construed as a mischievous, even malicious, attempt to embarrass his employer. After much publicity (even in the New York Times) the claim was dismissed by the Jockey Club, although the groom maintained that a substitution had occurred for the rest of his life - as did his two sons, who also worked at Eaton. Like "Silver Blaze", "Bend Or" was marked with a distinctive white "blaze" on his face. In the Holmes story the horse is disguised by covering this blaze, and after Holmes solves the mystery wins a race still disguised.

Conan Doyle leaves several clues that the "Silver Blaze" adventure involves a lot of money. As one comment on the story reads:

- "Everywhere in this story there is money, and lots of it. Starting with Silver Blaze's owner: it cost Colonel Ross £50 to enter Silver Blaze in the race (half of which would be forfeited if Silver Blaze was scratched form the Wessex Cup), and he stood to win £1,000 if his horse won, in addition to any additional wagers he would have made. This was ridiculously high finance for the era, when a single woman could live quite nicely on £60 per year. The corrosive effect of this much money floating around touches almost everyone in the story. Young Fitzroy Simpson, who had "squandered a fortune on the turf," and as a bookie had bet £5,000 against the favorite. Facing huge potential losses, he made lengthy road trip--and was willing to bribe servants--just to get some more information on the horses. The trainer of Desborough, Silas Brown, was "known to have large bets on the event," which is doubtless what caused him to conceal Silver Blaze after his initial reaction to simply return him. And of course, there is John Straker, whose massive debts led him to the conclusion that the only way to right his finances was by fixing the horse race."

Much the same is true of the real Epsom Derby: at least one bet of £3000 to win was laid on "Robert the Devil".

In recent years this tale has taken a very surprising turn. Research by Mim Bower of Cambridge University (Institute for Archaeological Research), first published in 2012, compared DNA of "Bend Or" (his skeleton was preserved at the Natural History Museum) to that of "Tadcaster" descendants and other relatives. Both chestnut colts were by the stallion "Doncaster" but "Bend Or" was out of "Rouge Rose" and "Tadcaster" was out of "Clemence". And the DNA results show that the 1880 Derby winner was out of "Clemence" making the winner not ""Bend Or" but "Tadcaster". The two had indeed been switched, either as foals or later - the skeleton known as "Bend Or" is most probably that of "Tadcaster". So the Conan-Doyle story "Silver Blaze" seems to be based on a suitably Sherlockian mystery that really occured.

...but what is at the cross?

The third part of the translation is well documented by imagery. Whatever was erected in the Roman Gardens in 1949 is what now stands outside St Peter's. This is shown very clearly in the Ketcham Home Movies: Europe 1951 which features Chester starting at 48:51 min into the video.

But is what now stands outside St Peter the "true cross"? Hemingway, the most believeable of several witnesses, writes that what was at Netherlegh was ornamented (if damaged) and refers to Hanshall's depiction of the cross as actually seen by Randle Holme. The cross fragment as supposedly supplied by Hugh Lupus Grosvenor is hardly ornamented at all, except around the lower part of the head where somewhat worn angels can be made out. But the head of the modern cross seems much too small as compared with Holmes drawing and the thickness of the shaft, and the placement and appearance of the angels differs significantly. Grosvenor was at the time (1880) involved in two very suspicious events: a dubious election that led to Chester being disenfrachised and what modern DNA evidence suggests may have been a race-horse swap (which even formed the basis of a Sherlock Holmes story).

So what of the object at Overlegh? The only image of this is from: Journal of the Architectural, Archæological, and Historic Society, for the County, City, and Neighbourhood of Chester, Volume 1 (1849-1855). According to the Journal, the "sketch is from a small water colour drawing in the possession of Mr T Topham" and while the watercolour cannot be traced, Topham was associated with CAAHS. The object is much more similar in proprtioms to the modern cross than that of Holme. While the object has the appearance of a gas lamp, its placement seems strange for such a lamp and there is nothing to suggest that the gas lines in Chester has reached Overleigh by the relevant time. The object is not the subject of any comment in the Journal, which dates from before the "rediscovery" of the cross by Grosvenor, and Overleigh has other mysteries associated with it, namely the "Cromwell Paintings" (see: Cowper), as well as collector of antiquaria: Dr William Cowper (1701-1767). However, by the 1830's the Cowper family were extinct in the male line. Overleigh was bought by Robert Grosvenor, 1st Marquess of Westminster and demolished in 1830 to allow construction of a new entrance to the Eaton Hall estate (Barrow, J. S.; Herson, J. D.; Lawes, A. H.; Riden, P. J,; Seaborne, M. V. J. (2005). "Manors and estates in and near the city". A History of the County of Chester), so whatever is shown in the "sketch" must date from before 1830.

Returning to Frank Simpson (A History of the Church of St. Peter in Chester: 1909), he described the "Ancient Cross" in these words:

- "The Anciant Cross formery stood in front of the church door: the exact date of its errection is not known, but we find it mentioned as far back as 1488. It was of very fine design: the upper part formed twelve panels, six above and six below: in the panels were figures of saints. This portion measures (including the orb at the top) about 7 feet 4 inches in height, and the stem and base probably measured about 8 feet in height, and the cross above the orb (which has entirely disappeared) about 12 inches, making a total height of about 16 feet."

Simpson's cross has a head which is two-and-a-half feet across, and this head is almost seven-and-half feet high. This bears no resemblence whatsoever to the reconstructed cross outside of St Peter. So, what is outside St Pater? One possible theory is that the "old" part of the cross is actually the pillar of a church font. Church fonts are generally octagonal, but hexagons, squares and even round fonts are known. Fonts do come and go - Broster tells us that church fonts were removed at the same time that the cross was pulled down, although no other writer repeats that statement. Curiously, there are two fonts just inside the door of St Peter. The more recent one is octagonal and the older one is oval. The oval one, like the fragments of the cross, also spent about 40 years in a garden (c1862-1908), according to what is written on a card within it:

- "This font is believed to have been originally placed in the church in the year 1662, and to have been in use for 200 years, when it was superseded by the present font. After lying unused for a while it was removed from the church, and was subsequently found in a garden in Chester. Through the kindly intervention of Canon Cooper Scott (the vicar of St John's Church) it was recovered and placed in its present position in the year 1908."

Could Hugh Lupus Grosvenor, in 1880 (a year when he really needed some positive comments in the press), have handed over to the Grosvenor Museum a fragment of the "cross" from Overleigh rather than from Netherlegh? If that is the case, then the High Cross at Chester may well be a "fake". On the other hand, it is possible that the drawing of the cross by Randle Holme that is referenced by Hanshall and Hemingway is not accurate, it may even have been drawn from memory after the cross was torn down during the Civil War, and that could explain why the cross shown in the drawing and that outside St Peter have a different carving of angels.

Browne of Netherlegh Family Tree

This is given in Earwaker as reproduced below. The male line appears to fail in the generation at the foot of the chart.

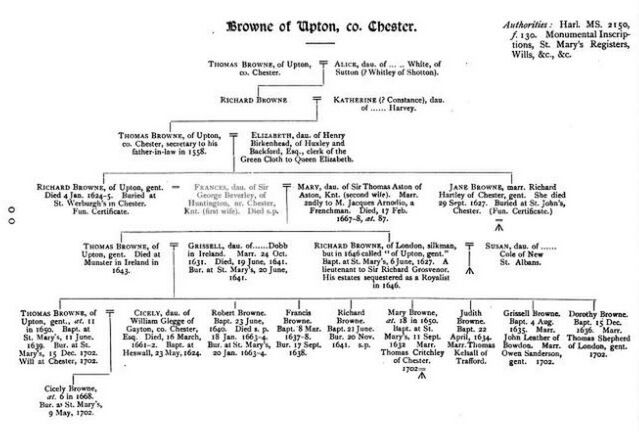

Browne of Upton

The Brownes of Upton are the more interesting of the two Browne families in Chester (Upton and Netherlegh).

Browne of Upton - Monuments

A good starting point for the story of the Brown(e)s of Chester is St Mary on the Hill, the original parish church of Upton, and where the Brownes provided many of the church-wardens. Earwaker's history of the church describes an early memorial board "formery placed against the north wall" (and since lost). The text (according to Earwaker) reads:

- "This was set up in the memory of Richard Browne, of Upton, in y* County of Chester, gent, sone and heire to Thomas Browne, by Elizabeth his Wife, daughter to Henry Birkenhead, Esq., Clerk of ye Green Cloth to Queen Elizabeth, sone and heir of Rich. Browne, sone and heir of Thomas Browne, of Upton, aforesaid. The abovesaid Rich d Browne died the 4 of January 1624, having had 2 Wives, first Frances, daughter to Sr George Beverley, of Huntington, Knt, who died without Issue, secondly to Mary, daughter to Sr Tho. Aston, of Aston, Knt, by whom he had Issue Thomas Browne of Upton and Richd of London. She afterfwards married Jacques Arnodio, gent, and dyed y° 17 Feb. 1668 5 Aged 87 Years. Thomas Browne sone and heire died at Munster in Ireland 1643: he married Grissell daughter to Dobb of Ireland, by whom he had Issue Thomas, Rob e, Francis, Richard, Mary, Judith, Grissell and Dorothy. She died in Childbed ye 19 of June 1641. Thomas Browne sone and heire married Cicely daughter to William Glegge of Gayton Esq, who died in Childbed of her Daughter Cicely the 16 of March Ano Dni 1661."

The Clerk of the Green Cloth was a position in the British Royal Household. The clerk acted as secretary of the Board of Green Cloth, and was therefore responsible for organising royal journeys and assisting in the administration of the Royal Household. Henry Birkenhead senior (1548-1613) was appointed to the office of Prenotary of the Counties Chester and Flint around 1600, and Henry Birkenhead junior (1572-1646) to the office of Custos Brevium of the same counties.

One notes something odd about the monomental board descibed above: it was supposedly set up by Elizabeth, the wife of the Richard Browne who died in 1578. "Elizabeth", despite having died in 1602, then goes on to describe events as late as 1661: three generations later. It is possible that a later member of the family had the memorial board text added to, and if so, it is likely that was the Thomas Browne who died in 1702. An alternative reading of the text is that "it was set up to the memory of RB who was son to TB (by his wife EB)"

However Hanshall gives a different text (with the section relating to the Brownes of Upton itallicised in the text given below):

- "Philippa wife of Thomas Browne, of Netherlegh, daughter of Tho. Berrington, of Chester, by whom he had 10 sons and 5 daughters; she died aged 42, May 6 1664 - The said Tho Berrington 1669 aged 42 having married to his second wife Jane, daughter Richard Leycester of Great Budworth, relict of Charles Levesby Chester who survived him - Ales daughter of Matthew Browne, of Netherlegh and wife of Thos Parnel of Chester obiit 5 Sept 1659. Matthew Browne gent obiit 24 Nov 1634. Richard Browne of Upton co Cest son & heir of Tho Browne by Elizabeth his wife to Henry Birkenhead Esq Clerk to the Green Cloth Q Eliz son and heir of Rich Browne son and heir of Tho Browne of Upton. This Richard Browne died Jan 4 1621, having had two wives; first Frances daughter of Sir Geo Beverley of Huntington Knt who died s.p. and 2d Mary daughter of Sir Thomas Ashton of Ashton Knt by whom he had Thos Browne of Upton, and Richard of London. She afterwards married Jaques Arnodie gent died 17th Feb 1668 aged 87 years. Thomas Browne, son died at Munster in Ireland having married Grisel daughter to --- Dobb of Ireland by whom he had Thomas, Robert, Francis, Mary, Judith, Grisel and Dorothy She died in Childbed 19th June 1641. Thomas Browne son and heir married Cicily daughter to Wm Glegg of Gayton Esq who died in Childbed of her daughter Cicily March 16 1661 --- Thomas Birkenhead gent Ales his wife; he died 12th November 1644; she died Jan 1691." ("died sp" means "decessit sine prole mascula" - died without male issue)

Richard Browne (b. 1562 - d. Jan 1624/5)

In 1587-8 Richard Browne sold land in Upton and Wervin to Henry Birkenhead (of Backford Hall). Called The Acres, it consisted of 16 acres in all lying between Upton Common, Wervin Common and the high road that led to Caughall. Secondly, in 1595-6 Richard Browne again sold land, this time to Will Aldersey. Called Great Acres, it had a value of £80 and was again in the vicinity of the first sale.

Richard matriculated at Brasenose on 4th July 1579 at the age of 17 and by 1583 was a law-student at the Inner Temple in London, where he gave his address as Hoole. Richard is the eldest brother of Thomas, father to Sir Thomas Browne, and like Thomas evidently moved to London (at least to study). He must have returned to Chester as his youngest son Richard (who was born close to the time of his death) was baptised at St Mary on the Hill. Richards other siblings include Edward, uncle to Sir Thomas. Edward, who became a grocer, was admitted to the King's School in 1582, also appears to have moved to London (with his brother Thomas and another brother, William).

Brothers Thomas (d. 1643) and Richard (bapt 1627) Brown

The unfortunate Richard Browne of London (Sir Thosas cousin) is described as a London silk merchant prior to 1646 and then afterwards described as "of Upton". His lands were sequestered in 1646 (when he was aged about 20) and he oompounded for his estate at £24/15s. Given his relatively young age he can hardly have done much in the Civil War. Richard's father, another Richard, died at about the time of Richard's birth in early 1625. It is worth noting that he was not the only member of the Browne family who had moved to London to enter the trade of a mercer (silk merchant) at about this time - Thomas (d. 1613) father of Sir Thomas Browne had done the same. Curiously, at about the same time, the family of a future wife of the founder of Brown's department store were seemingly already engaged in the London-Chester fashion trade.

It is very likely Richard Browne returned from London to Chester following the death of his elder brother, Thomas Browne of Upton, who died in Munster (Ireland) in 1643. Richard's sister-in-law (Grissell) had died in June 1641 (while giving birth to son Richard, who died in November of the same year) and his nephews, with the exception of one minor (Thomas b. circa 1639) had all pre-deceased his brother. Whether Thomas Browne who died in 1643 had any involvement with the ongoing war in Ireland is unknown but there was a minor battle at Cloughleagh (4 June 1643) involving Royalist troops from Munster, where this somewhat tragic Richard Browne died.

A look at the amcestral tree of the Browne's of Upton shows that the direct male line was reduced to a single member in and shortly after the time of Richard Browne. While the young nephew Thomas (b. 1639) would survive and marry Cicely Glegge, they would only have a single daughter at whose birth (March 1662) Cicely Glegge would herself perish.

Browne of Upton Family Tree

Earwaker gives the pedigree reproduced below:

Using Earwaker, Hanshall and other sources (see sources and links) it is possible to tentatively re-create a slighly more extensive pedigree of the Browes of Upton as follows:

- Thomas Browne of Upton = Alice Whitley of Shotton

- *Thomas Browne = Katherine Harvey (lived in Upton)

- *Thomas Browne (b. 1540 - d. 1578) = Eizabeth Birkenhead (d. 1602) - last common ancestors (grandparents) of the Brownes of Upton and Sir Thomas Browne

- *Richard Browne (b. 1562 - d. Jan 1625 - lived in Hoole) = (1) Francis Beverley (no issue) = (2) Mary (d. 1668) (daughter to Sir Thomas Aston (1547-1613), see:Civil War and Brereton - she later married Jaques Arnodio - "a Frenchman")

- *Thomas Browne (b. 1540 - d. 1578) = Eizabeth Birkenhead (d. 1602) - last common ancestors (grandparents) of the Brownes of Upton and Sir Thomas Browne

- *Thomas Browne (d. 1643 in Munster (Ireland)) = Grissell (d. 1641)

- *Thomas Browne (bapt. 1639 - d. 1702) = Cicely Gleggge of Gayton (bapt. 1624 - d. 1661)

- *Cicely Browne (b. 1661 - d. 1702)

- *Robert Browne (bapt. 1640 - d.1664)

- *Francis (b. 1640, died young)

- *Richard (b. 1641, died young)

- *Mary (b. 1632) = Thomas Critchley (had issue..)

- *Judith (b. 1634} = Thomas Kelsall

- *Grissell (b. 1635) = (1) John Leacher = (2) Owen Sanderson

- *Dorothy (b. 1636) = Thomas Shepherd

- *Thomas Browne (bapt. 1639 - d. 1702) = Cicely Gleggge of Gayton (bapt. 1624 - d. 1661)

- *Thomas Browne (d. 1643 in Munster (Ireland)) = Grissell (d. 1641)

(other children of Richard Browne and Mary)

- *Richard Brown (bapt 1627; later moved to London) - estates sequestered in 1646 (returned to Chester following death of elder brother) = Susan Cole (of St Albans) (had issue..)

(other children of Thomas Browne and Elizabeth - from her 1602 funeral certificate)

- *Jane Brown (d. 1627) = Richard Hartley (had issue..)

- *Henry (d. in Oxford around 1580, aged 19)

- *Edward (moved to London)

- *Francis

- *Anne = (1) John Smethwick, (2) John Dutton

- *William (moved to London)

- *Fernando

- *Hugh

- *Thomas (moved to London, d. 1613) = Anne Garraway (her second marriage was to Sir Thomas Dutton)

- *Sir Thomas Browne (1605-1682) = Dorothy Mileham (1621-1685)

- *Edward (1644–1708)

- *Thomas (d. 1710)

- *Elizabeth (b. 1648 - d.after 1728) = Captain George Lyttelton (b. 1593 - son of John Lyttelton MP - d. 1717)

- *Anne

- *Frances = Henry Fairfax

- *Frances Fairfax (d. 31 Jul 1719) = The ninth Earl Buchan

- *Edward (1644–1708)

- *Sir Thomas Browne (1605-1682) = Dorothy Mileham (1621-1685)

(other children of Thomas and Anne - Sir Thomas sisters)

- *Anne = John Palmer

- *Jane = Thomas Price (1599-1685) - translated to the archbishopric of Cashel on 20 May 1667

- *Mary = Nevill Craddock

Sir Thomas Browne

After Thomas Browne of Upton moved to London, his son (later Sir Thomas Browne) eventually prospered and became the once noted writer who is largely forgotten today. In Sir Thomas own words (omitting his part in Witch Trials):

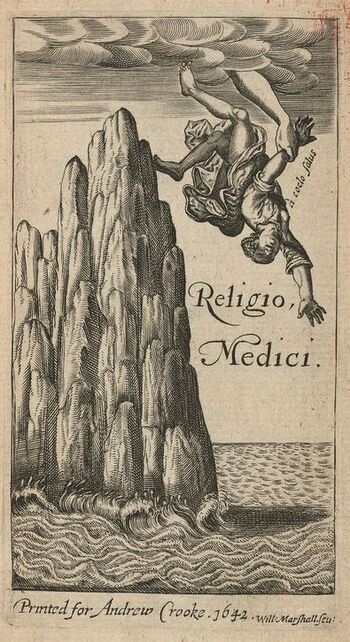

- "..I was born in St Michael's Cheap in London, went to school at Winchester College, then went to Oxford, spent some years in foreign parts, was admitted to be a Socius Honorarius of the College of Physicians in London, Knighted September 1671, when the King Charles II, the Queen and Court came to Norwich. Writ Religio Medici in English, which was since translated into Latin, French, Italian, High and Low Dutch, Pseudodoxia Epidemica, or Enquiries into Common and Vulgar Errors translated into Dutch four or five years ago. Hydriotaphia, or Urn Buriall. Hortus Cyri, or de Quincunce. Have some miscellaneous tracts which may be published.."

Early Years

Sir Thomas Browne was born in 1605, the third year of James I and just a few years before the publication of "Novum Organum" by Francis Bacon. The title of Bacon's work is a reference to Aristotle's work Organon, which was his treatise on logic and syllogism. In Novum Organum, Bacon details a new system of logic he believes to be superior to the old ways of syllogism and sets the scene for science to develop various methodologies, because he made the case against older Aristotelian approaches to science, arguing that method was needed because of the natural biases and weaknesses of the human mind, including the natural bias it has to seek metaphysical explanations which are not based on real observations. As will be seen, Browne did not entirely abandon the superstitions of earlier days: the believed in astrology and gave evidence before at least one witch trial. However he stands on the cusp of the "age of reason" when "free rational inquiry" superceeded religion and other forms of dogma.

Browne’s father, Thomas, had come in early manhood from Chester to London, where he was a mercer, or silk merchant. According to the most prevalent version, here he married Anne Garroway of Acton, Middlesex and they lived in comfortable circumstances with their son and four daughters. In the "Pedigree of Sir Thomas Browne" (see link below) a different version is given:

- "The mother of Sir Thomas Browne was Anne, daughter of Powle Garraway of Lewes. She was married to Thomas Browne, mercer, of the parish of St. Michael-le-Querne, Cheapside, before 1605, in which year Sir Thomas was born. He was the youngest of four children — two sons and two daughters."

Browne himself is the only source for his mother having lived in Lewes, and does not help matters: writing to son Edward in the last winter of his life, Browne remembers "being carried to his grandfather's house in Lewys". This has been taken to suggest that his mother was born there, although it could equally mean that his grandfather moved there later. Also, note that the "Pedigree" states that Browne was the youngest of two sons and two daughters - this appears to be untrue, with Thomas having three surviving sisters out of a possibly larger number of siblings, at least one of whom appears to have died young.

The Silk Trade

Italy had a thriving silk industry from the 13th century and France from the 15th century, using both black and (predominantly) white mulberry leaves to feed their silkworms. In 1559 silk fabrics constituted 3.3% of imports and 5.1% in 1622. Raw silk was 1.1% of imports in 1559 and 7.5% in 1622. During the 17th century as a whole, silk imports constituted from 23% to 29% of the value of all imports. By the late 17th century, silk, either raw, or as silk thread worked especially by the weavers in Spitalfields, London, was the most valuable of all raw material imports to England. In 1609 King James I attempted to kick-start a strategic, native silk industry. Ten thousand trees were imported from all over Europe, and the king required landowners “to purchase and plant mulberry trees at the rate of six shillings per thousand”. But James made the mistake – some say he was deliberately wrongly advised by the perfidious French – of ordering the black mulberry instead of the white version. The latter is the natural food of silkworms but grows less well in England. Within a few years the silkworm project failed.

Brownes father had apprenticed himself Master Richard Barnes and paid three shillings are fourpence for his freedom in 1594. He became a member of the Mercers Livery Company in October 1604. The birthdate of the father must be prior to around 1578 (when his own father died) so he was at least 16 when he became "free" and possibly not that much older as he died quite young with a pregnant wife mentioned in his will.

Education

The senior Browne died in 1613 when his son was eight years old. After the death of Thomas Browne senior Anne married Sir Thomas Dutton, and this remarriage within only six months of her bereavement led to intervention of the Court of Orphans of the City of London into the disposition of the will. Her dead husband's elder brother Edward had been a fellow executor but Anne had proceeded to probate in his absence, and the Court questioned her declaration that Thomas Browne had died with negligible wealth. In truth he had about £6000, owed about £11,000 and was himself owed more less the same. Eventually Anne was excluded from the executorship and Thomas Jr.'s uncle Edward was appointed to act alone — to the lasting benefit of the young Thomas and his sisters, it also apparently left sufficient means for the sons education. Accordingly, the boy was sent to Winchester College in 1615 (aged 11).

William of Wykeham’s famous school (set up to educate "poor" sons of the lower gentry) was Anglican and Royalist, and provided a sound classical education that was a good foundation for the erudition acquired by Browne in later years. He remained at Winchester for eight years, until, in 1623, he proceeded to Oxford. After failing to get into New College following what may well have been aa rigged examination, he matriculated at Broadgates Hall, which soon afterward was upgraded to become Pembroke College. Browne, although only a freshman, was called upon (August 1624) to deliver a Latin oration at the inauguration ceremony.

Step-father Sir Thomas Dutton (d. 1634) had served as a soldier in the Low Countries and (in 1610), barely survived a bloody and barbaric duel with a superior officer on Calais Sands. In June, 1610, he was at the siege of Juliers and in the heat of the action exchanged some wounding words with his superior officer, Sir Hatton Cheke: the two meb had long been at enmity. Five months later they settled it, each armed with dagger and rapier for a duel in which Sir Hatton Cheke was killed. The bizarre scene is preserved for us by Thomas Carlyle, writing nearly a century later in his "Historical Essays":

- "After some brief flourishing and flashing, the gleam of the swift clear steel playing madly in one’s eyes, they, at the first pass, plunge home on one another: home with beak and claws: home to the very heart. Cheke’s rapier is through Dutton’s throat from before and his dagger is through it from behind: the windpipe miraculously missed; and in the same instant Dutton’s rapier is through Cheke’s body from before, his dagger through his back from behind: lungs and life not missed; and the seconds have to advance, pull out the four bloody weapons, disengaging that hell - embrace of theirs... Cheke reels down dead in his rage and had a bloody burial there that morning."

Dutton was evidently a braggart with debts but royal favour: King James made him "Scoutmster General" of Ireland for life - a position with a substantial salary.

Winchester would have afforded the boy little or no opportunity for study of the natural sciences (until the 1860s the predominant subject of instruction for Wykamites was classics), so it was probably during the school holidays that he began to acquire his knowledge of natural history.

At Oxford a chair of anatomy was just being established (the Chair of the Tomlins Readership in Anatomy was founded 1624) in addition to several other chairs of physical sciences. Browne’s teachers included Dr. Clayton (last Principal of Broadgates Hall and first Master of Pembroke), an anatomist and Regius professor of medicine, and Dr. Thomas Lushington, a mathematician and clergyman (and so fond of a drink that he eventually became the original "lush"). Clayton’s influence directed Browne’s attention to the study of medicine and human anatomy, but this could not begin seriously until he had taken his M.A. in philosophy in 1629.

Travels

He then left Oxford and spent some weeks in Ireland with his stepfather, Sir Thomas Dutton (a member of the Cheshire Duttons), before proceeding to Montpellier for full training in medicine. On his journey to see his stepfather (or his return) he may well have visited Chester - the Duttons of course had relatives nearby, and it was a principal port for the voyage to Ireland. Confirmation that he did visit Chester (on his return from Ireland) comes from a poem (in two versions) written by Browne, about his experiences of the stormy seas between Dublin and Chester. Writing to his worried daughter Elizabeth in September 1681 (she was married to a sea-captain and had just seen a ship founder), Browne includes a copy of the poem and recalls:

- "I came once from Dublin to Chester at Michaelmas and was so tossed, that nothing but milk and possets would goe down me 2 or 3 days after.."

He might even have met somewhat tragic brothers Thomas and Richard Browne in Chester. The truly remarkable thing about the poem ("A tempest at sea") - said to be annotated: "at the Crowe Inne in Chester at his Coming from Ireland" - is that it has the same metrical structure as "Those in Peril on the Sea" (more properly known as "Eternal Father, Strong to Save") written some hundreds of years later (1860) by William Whiting (1 November 1825 – 3 May 1878) an alumni and later headmaster of Sir Thomas' old school - Winchester - who was almost certainly familiar with Sir Thomas' work, although no link between the two works has ever been proved. Browne's verse is:

- "In vayne we do the Pilot coart / the bottome of the sea's our port / no Anckers in the sea wee cast; / Our Ancker is in heaven fast. / our only hopes on him wee Laye / to whom both Seas and winds obeye."

The later hymn is:

- "Eternal Father, strong to save / Whose arm hath bound the restless wave / Who bidd'st the mighty ocean deep / Its own appointed limits keep / Oh, hear us when we cry to Thee / For those in peril on the sea!"

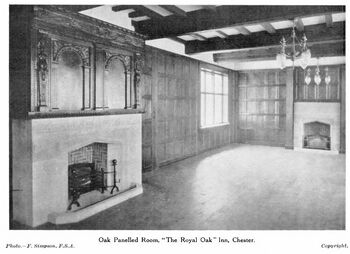

An inn caled "The Sign of the Crow" existed in Chester from a first mention in 1580, until it became "The Royal Oak" by 1703. The pub (at 44 Foregate Street) sadly closed down in the 1980s and later became a branch of the electrical retailers Dixon's, and then Curry's, which in turn closed in 2009: it is now a health food store. The Chester Historian Frank Simpson wrote a detailed article on the "original" building.

It is not known how long Browne remained in France, but his travels in several European countries cannot have occupied less than four years. Details are scanty and his journey took place when Europe was being ripped aapart by the Thirty Years War (1618-1648). England and France were at war in 1627, but made peace in 1629 - making travel possible, but not easy. During his stay in Montpellier he made notes on the metamorphosis of the moth into a silkworm, as that was a local industry and Browne was familiar, from his father, with silk.

He probably spent some time in Padua, but his final goal was Leiden, where he defended his thesis and received his M.D. in December 1633. A university city since 1575, Leiden has been one of Europe's most prominent scientific centres ever since. During these travels he studied many subjects besides medicine, absorbing information of all kinds and acquiring knowledge of several modern languages. As will be seen, Thomas encouraged his children, including son Edward, to travel in the pursuit of knowledge and experience. As for himself, after his youthful travels, he mostly stayed in Norfolk once settled down and there is no evidence that he ever left the county after he moved there.

Apprentice

English regulations required a medical man with a foreign degree to practice for four years with an established doctor before being allowed to have his M.D. by incorporation at Oxford or Cambridge. It is probable that Browne spent some of these years of apprenticeship somewhere in Oxfordshire, but no details are known. It has also been suggested he spent some time in Shibden (Yorkshire). He took his M.D. at Oxford on 10 July 1637 and was then, at the age of thirty-two, free to practice anywhere that he chose. It was during these four years that Browne wrote his most famous book, Religio medici, which was not published officially until 1643.