Upper Reaches

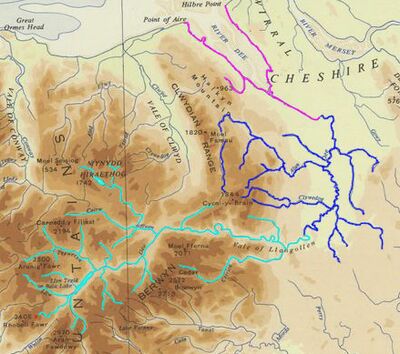

We have divided the story of the River Dee into three parts:

Upper Reaches

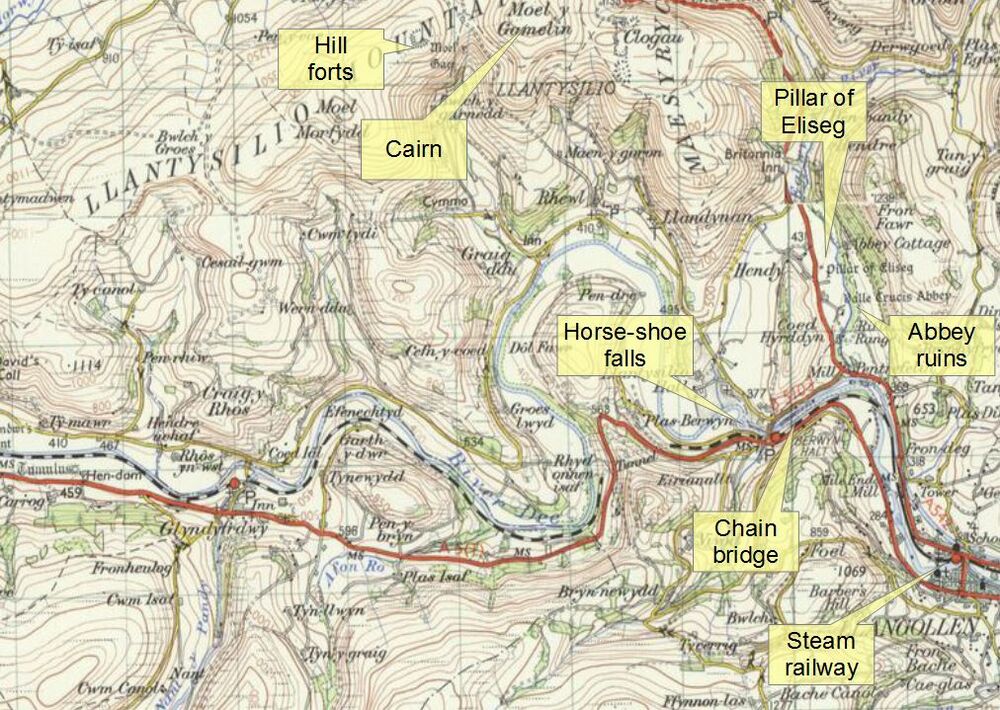

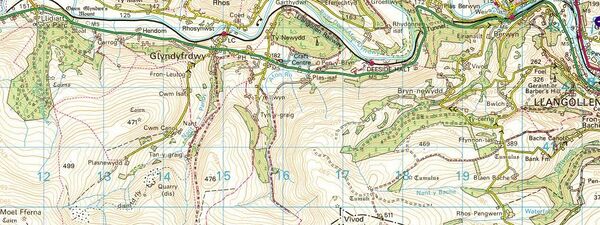

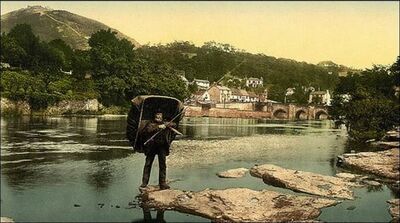

From the source of the river at springs on the slopes of Dduallt above Llanuwchllyn in the mountains of Snowdonia, through Wales, to its emergence from the Vale of Llangollen; here the young river flows swiftly and the majority of erosion takes place, cutting relatively narrow, steep-sided, "V"-shaped valleys, often with interlocking spurs.

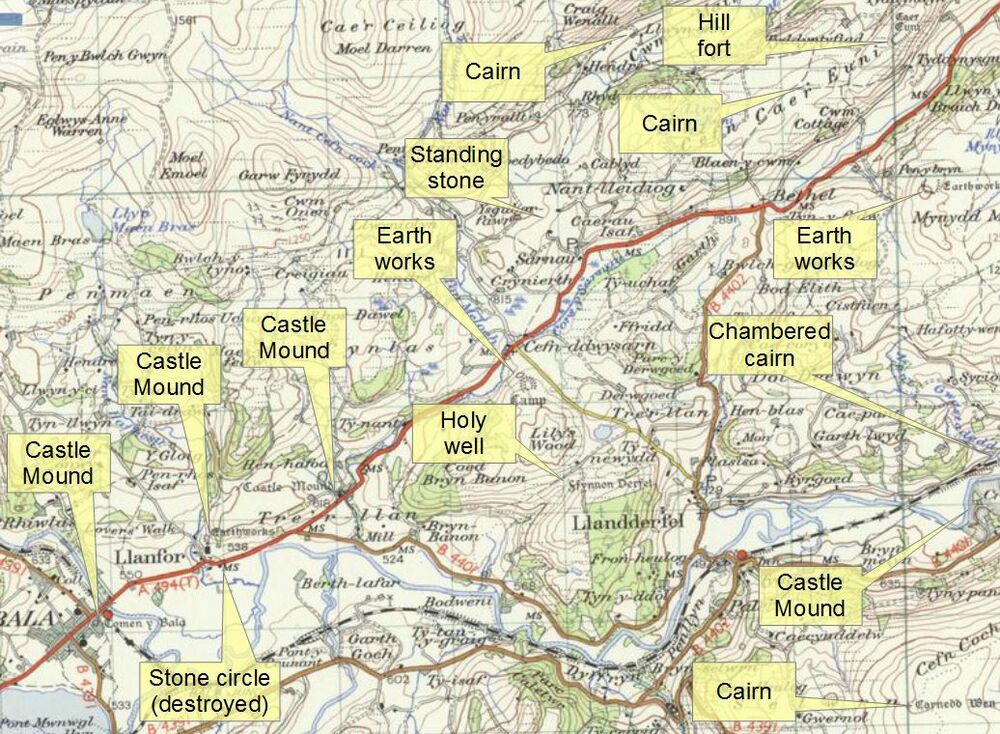

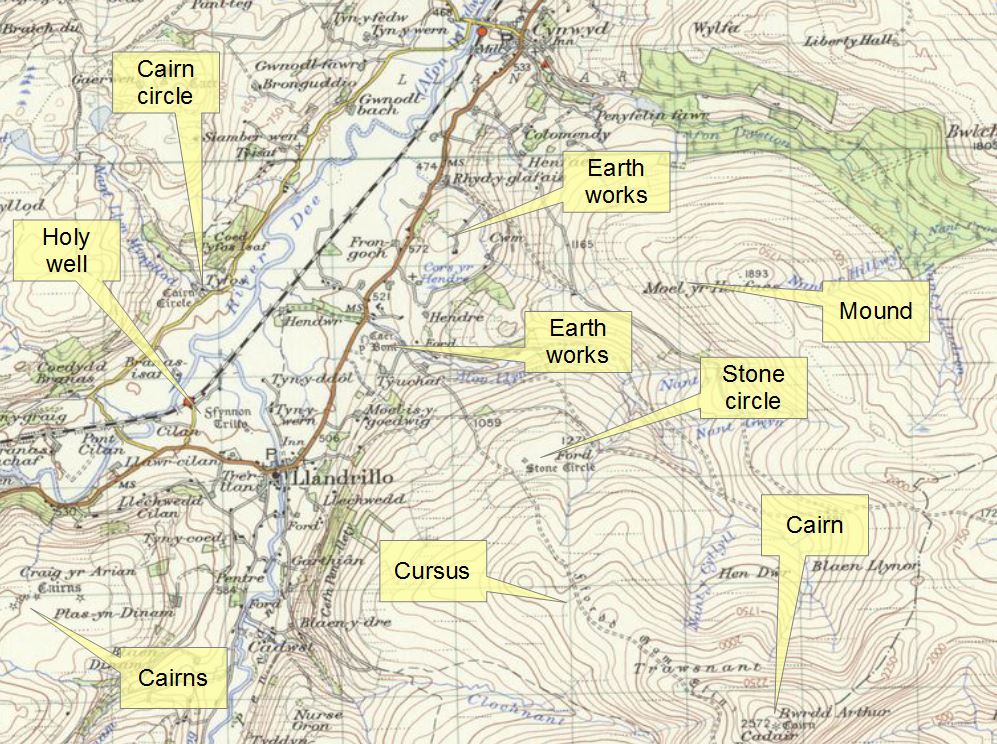

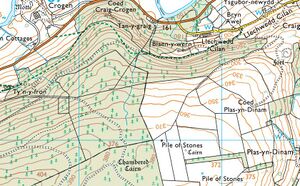

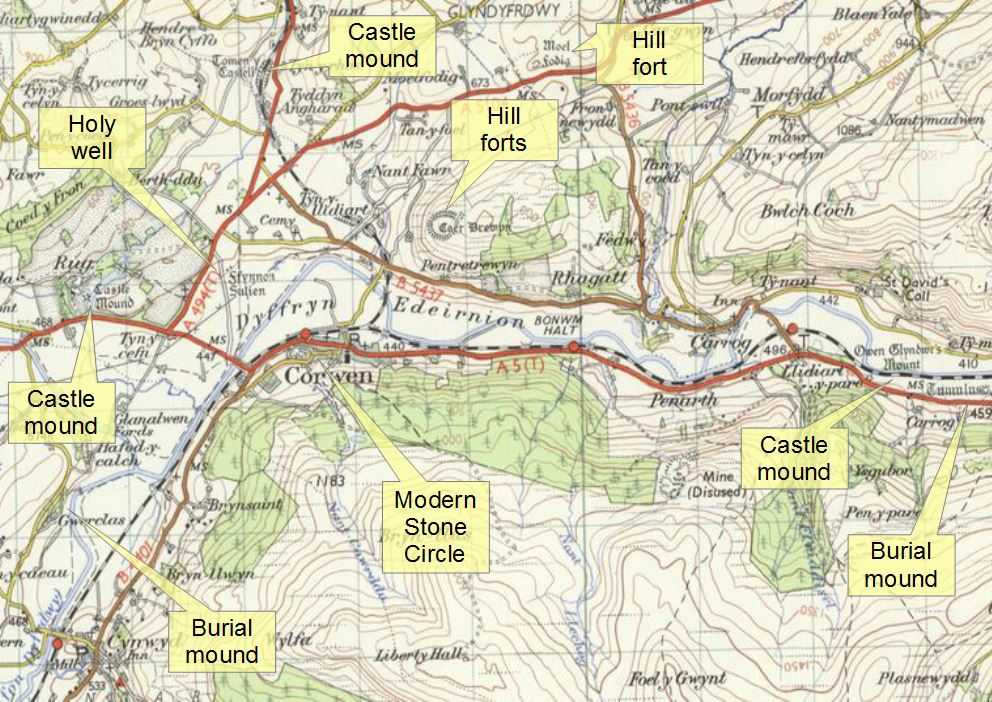

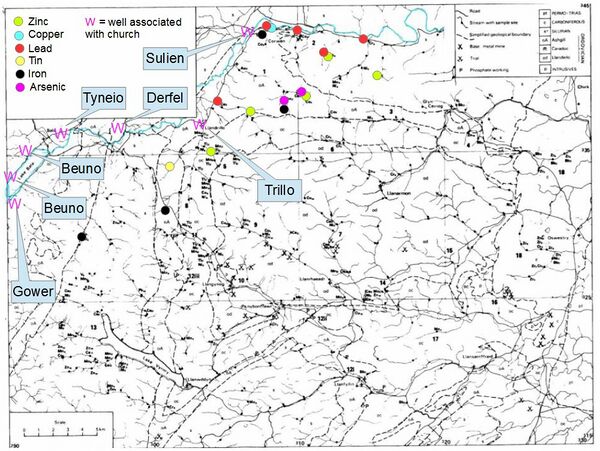

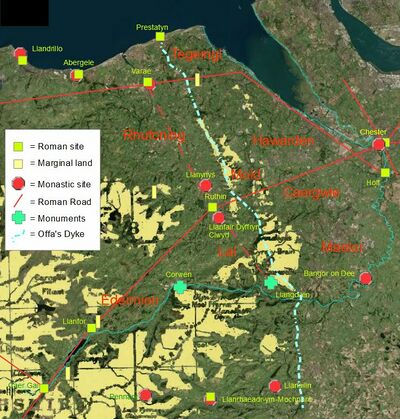

Hillforts, cairns and stone circles dot the landscape. Later fortifications come from the Romans (see Roman Chester and Dark Ages) and the Normans (see Earls of Chester). Almost every old church has its holy well dedicated to its founding saint. Modern archeaological studies have vastly multiplied the numbers of sites of interest, but many down in the valley of the Dee many sites have been "ploughed flat", with a much better survival rate at higher elevations.

Middle Reaches

Through England and the Welsh borders to Chester; the "middle aged" river slows down and the valley becomes broader. Both erosion and deposition of material takes place, leading to the formation of meanders and occasional changes of course which have in cases left pockets of England "stranded" on the Welsh side of the River Dee.

Lower Reaches

Back in Wales, below Chester to Hilbre Islands and the sea; the river is now in "old-age" and while there is little erosion a lot of material is deposited. In the case of the River Dee this deposition has had a significant impact on the economic development of Chester, effectively turning a major port into a relatively quiet backwater. The estuary is important for birdlife and has been designated both as a "Site of Special Scientific Interest" and under the "Ramsar Convention" on "Wetlands of International Importance", especially as waterfowl habitats.

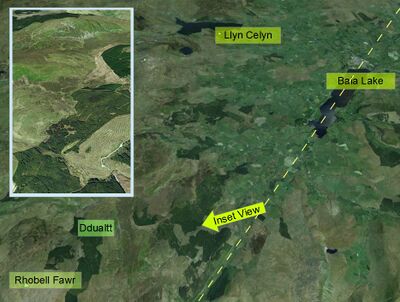

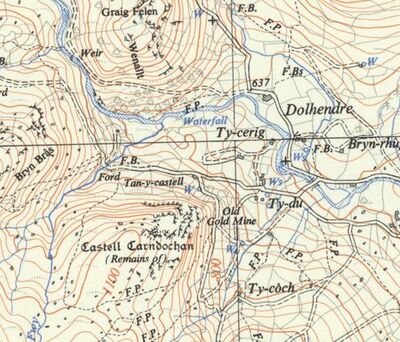

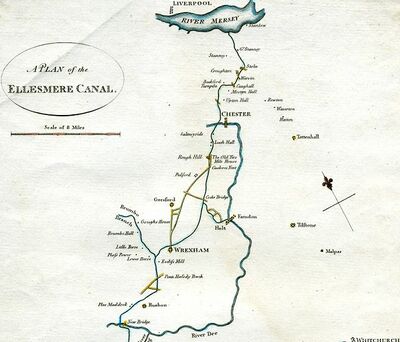

Map - Source to Bala Lake

Upper Reaches

The Dee is the largest river in North Wales with a catchment area of more than 1,800 km2. It is one of the most highly regulated rivers in Europe, and along with Llyn Tegid it has been designated as a Special Area of Conservation (SAC). From its headwaters in the uplands of Snowdonia, the Dee descends via Llyn Tegid (Bala Lake), the largest natural lake in Wales. After flowing through a broad valley to Corwen, it tumbles eastwards through the spectacular Vale of Llangollen, under the famous Pontcysyllte Aqueduct World Heritage Site, before breaching the Welsh foothills near Bangor-on-Dee, and meandering northwards through the Cheshire plain to its tidal limit just below Chester. The River Dee is fascinating in many ways: especially in terms of geology and human history. It would be impractical to tell every story associated with the river in this article, so there are many pointers along the way to other sources of information.

In its upper reaches, the Dee flows rapidly and its channels erode deeper rather than wider. The valley is steeped in myth. References to Gwyn ap Nudd, Lord of the Celtic Otherworld, are commonplace in the area, with the name for the Berwyn range perhaps translating to Gwyn's Hill. Others include Nant Gwyn (Gwyn's Valley), Caer Drewyn (Gwyn's Town) - the whole area has been known locally as Gwyn's Land (Gwynedd) for centuries. "Gwyn" means "white" in the Welsh language and is in everyday use as a common noun and adjective with that meaning. "Albion" (Greek: Ἀλβιών) is also one of the oldest known names of the island of Great Britain, and is often taken to mean "the white country", perhaps a reference to the white cliffs of Dover or the pale skin of it's inhabitants.

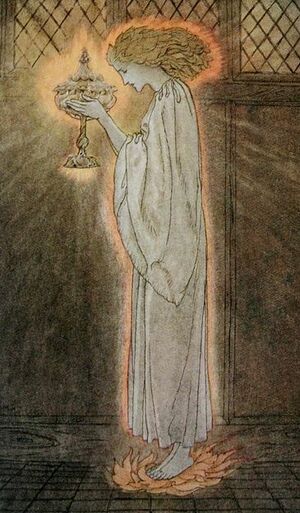

The upper reaches of the river Dee are associated with Arthurian legends - Arthur was said to have grown up at the source of the Dee and the castle of Dinas Bran (lit "Castle of the City of Crows") is supposed by some to be "Corbenic" the home of the Fisher King. The feminine form of Gwyn, Gwen, is the root of "Gwenhwyfar", the original Welsh form of Guinevere. More recent legends include that of the "Welsh Roswell". The upper reaches of the River Dee are highly regulated to maintain a more or less constant supply of water throughout the year, but once the river was noted for its floods. The Dee is only about 30th on the list of UK rivers by length, but one of the most well-populated with sites and stories of interest.

Willam Camden wrote:

- The river Dee, called in Latin Dava , in British Dyfyr-dwy , that is, the water of Dwy , breeding very great plenty of Salmons, ariseth out of two fountaines in Wales, and thereof men thinke it tooke the name. For dwy in their tongue signifieth two. Yet others, observing also the signification of the word, interpret it Blac-water , others againe Gods water or divine water. But although Ausonius noteth that a Spring hallowed to the Gods was named Diuvona in the ancient Gaules tongue (which was all one with the British), and in old time all rivers were reputed Διοπετεῖς, that is, Descended from Heaven , yea and our Britans yeelded divine honour unto rivers, as Gildas writeth, yet I see not why they should attribute Divinitie to this river Dwy above all others.

A different world

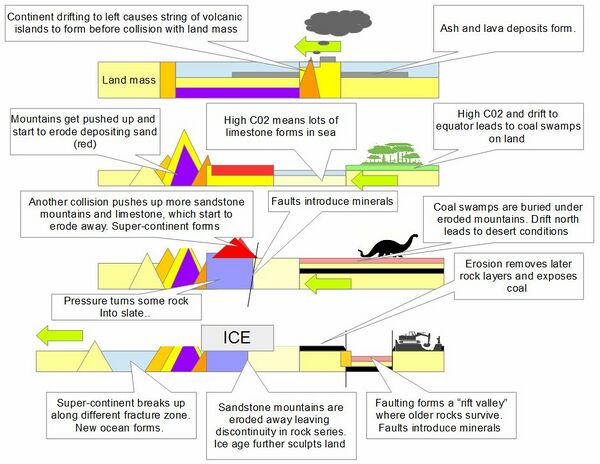

Early geologists strove to explain how fossil fish and shells could be found on the higher slopes of mountains, as they can still be found today in the mountains around the Dee valley. The first explanation was Noah's Flood and led to the theory of "Catastrophism" where the earth was shaped by sudden and often cataclysmic changes. This was later displaced by "Uniformitarianism" which believed that one should look no further for the causes of geological change than to processes which are still going-on today. These would include, for example everyday erosion by rain.

The truth is somewhere between the two. Rain still washes mountains slowly to the sea, grouse still swallow small stones to aid digestion and deposit them elsewhere and meandering rivers sort and scour their flood-plains, but now and again these processes reach a tipping point as drifting continents collide, volcanic pressures reach bursting point or the climate switches from greenhouse to ice-house. Sometimes there are genuine catastrophes, as wayward comets slam into the earth or when a new species, in the blink of a geological eye, modifies the entire planet in a few hundred years. In order to make sense of the history of the rocks, geologists divided them into three "eras", oldest (pre-dinosaurs), middle (with dinosaurs) and youngest (after the dinosaurs). They later added a forth era and started to separate the three eras up into "periods" (as well as adding some previous "eons" of even longer timescale). Nowadays the geological past of the earth is thinly sliced into eons, eras, periods, epochs, ages and "chrons" (and every geologist wants to name a new one).

Our story of the River Dee starts in the deep past, in the period informally known as the "Pre-Cambrian" (literally - "before the Welsh mountains"). It spans from the formation of Earth around 4500 Mya (million years ago) to the evolution of large hard-shelled animals, which marked the beginning of the Cambrian, the first period of the first era of the "Phanerozoic" eon, some 542 Mya. It is named after the Roman name for Wales - Cambria - where rocks from this period were first studied. Little is known about the Precambrian, despite it making up roughly seven-eighths of the Earth's history. Most of the Earth's landmasses were collected into a single supercontinent around 1000 Mya ("Million Years Ago"), known as Rodinia (from the Russian for "the mother-land"), which broke up around 600 Mya when glacial conditions possibly reached all the way to the equator, resulting in a so-called "Snowball Earth". In those long gone days the Earth was very different from the world we know today - there was no life on land, apart perhaps for some algal scum, and the day was shorter by as much as two hours as the earth rotated more quickly. The tidal drag of the moon would slow the earth down over hundreds of millions of years. Such was the birthplace of the Welsh mountains, eventually to become the head of the Dee.

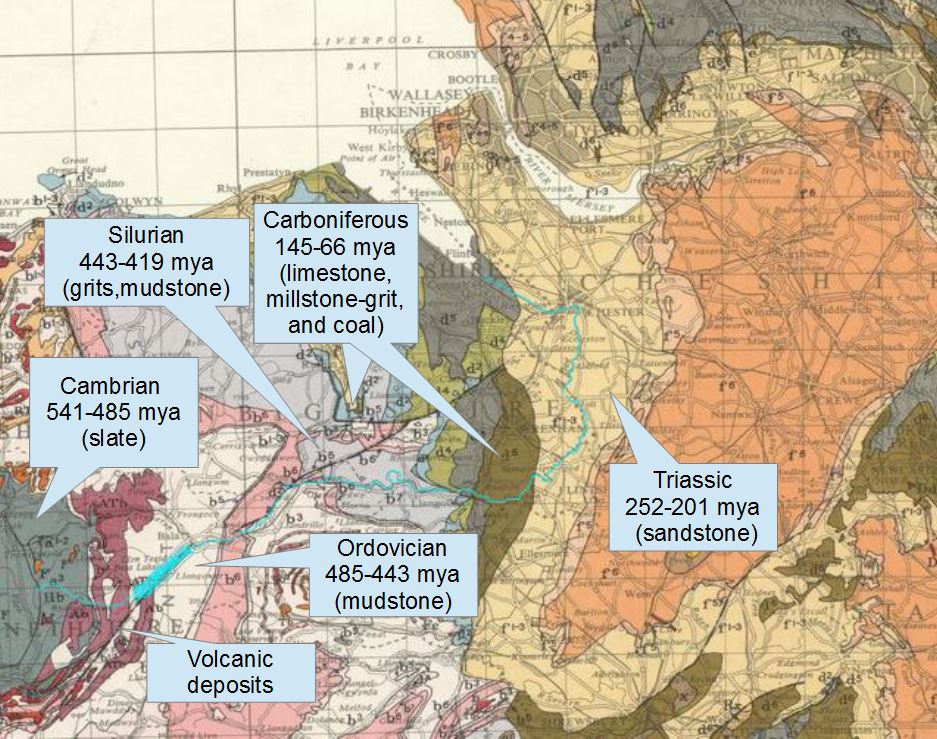

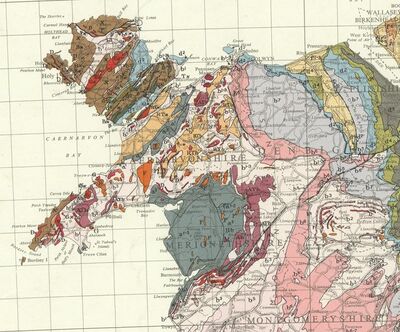

The atmosphere of this early Earth is poorly understood, but it is thought to have been "reducing" gases, containing very little free oxygen. The young planet had a reddish tint, and its seas may have been olive green. Evolving life forms, such as cyanobacteria, developed photosynthesis, and oxygen began to be produced in large quantities. While animals need oxygen to survive, it was a toxic gas to early life causing an ecological crisis sometimes called the "Oxygen Catastrophe" (or, "Oxygen Crisis", "Oxygen Holocaust", "Oxygen Revolution", or even "Great Oxidation"). The oxygen was at first immediately tied up in chemical reactions, primarily with iron (as rust), until the supply of oxidizable surfaces ran out. After that the modern high-oxygen atmosphere developed. This eventually killed off most of the early life forms for which oxygen was a waste-product and poison. Rocks of the subsequent Cambrian period are only preserved in Pembrokeshire to the West and Snowdonia to the North and include the slates of Snowdonia and the hard rocks of the "Harlech Dome", formed when the Caledonian collision compressed the rocks of the Harlech region into large folds, and raised them into a huge dome. Apart from a few outcrops the original Cambrian mountians have long been eroded away or buried deep below subsequent deposits. The oldest rocks found in Britain are the more than 3000 million year old (mya) rocks in the Hebrides. In Wales the oldest outcropping rocks, in Angelsey for example, are a "mere" 700 mya. The Cambrian rocks of the Harlech Dome were laid down some 500 mya.

Source

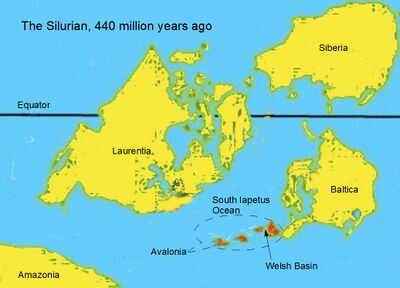

When the supercontinent of Rodinia split it prduced three major pieces: the supercontinent of Proto-Laurasia (North America, Greenland, Europe and the former USSR), the supercontinent of Proto-Gondwana (parts of South Ameica, Antarctica, Madagascar, India, and Australia), and the smaller Congo craton. Next Proto-Laurasia split to form the continents of Laurentia, Siberia and Baltica. The Iapetus Ocean formed a wide oceanic basin between the paleocontinents of Laurentia (Scotland, Greenland and North America) to the west and Baltica (Scandinavia and parts of northeastern Europe) to the east. A smaller sub-continent, called "Avalonia" also lay on the south side of the Iapetus Ocean. On the northen side of Avalonia lay a marine basin, termed by geologists the ‘Welsh Basin’. While the extent of the Welsh Basin varied with changes in sea level, it stretched roughly from the English Midlands through Shropshire to Ireland. In shallow Cambrian seas there was often precipitation of various chemicals. These included Manganese deposits which would later contribute to the economy of the River Dee catchment area.

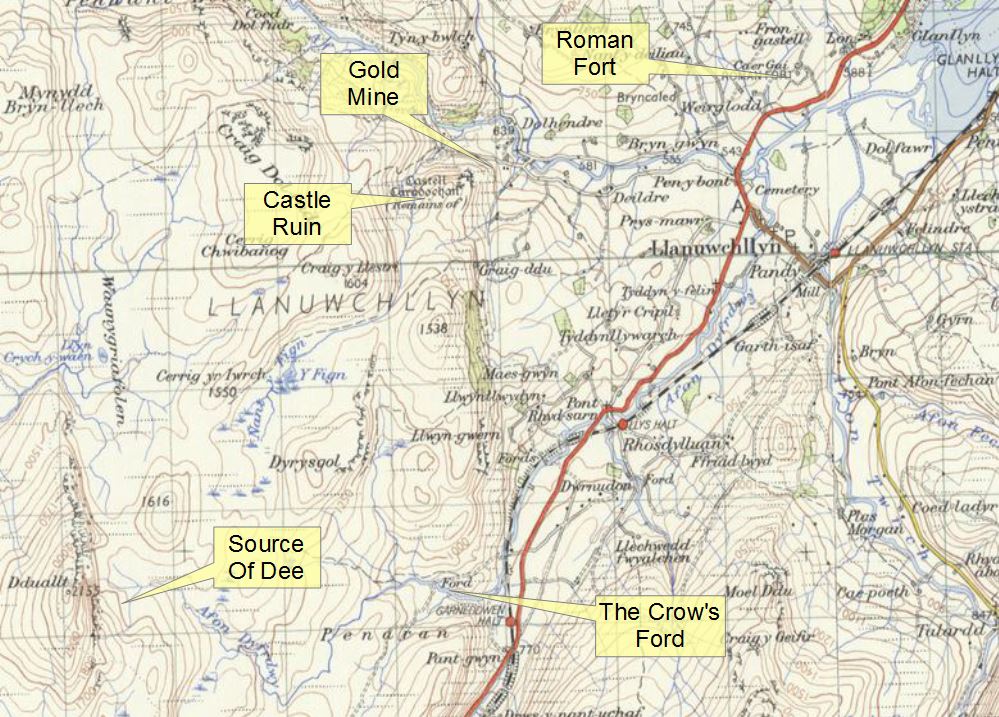

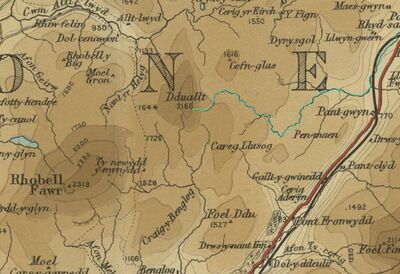

The present-day River Dee has its source on the slopes of 662m Dduallt (ðɨæɬt - "Black Hill") above Llanuwchllyn in the mountains of Snowdonia. A peculiar story about this mountain is recounted by George Bolam ("Wild Life In Wales", p387) who was crossing the Dduallt range with a farmer when they came across the material which is known locally as "pwdre ser" (rot from the stars). This "star-jelly" has been suggested as being some kind of mysterious extra-terrestrial goo which fell with meteors, but there are more mundane proposals for it's origin - DNA analysis shows it is possibly formed from the glands in the oviducts of frogs and toads. Birds and mammals will eat the animals but not the oviducts which, when they come into contact with moisture, swell and distort. However this is a good place to start with the geological journey, for the formation of the earth itself is believed to have been completed by an intense period of "falling stars" - the "late heavy bombardment" whose scars we still see on the face of the Moon.

Switching to the human journey, once the headwaters of the Dee were the land of the Ordovices, a tribe that lived here before the Romans came and whose name could be in some way related to the word for "hammer"; Irish 'Ord', Welsh 'Gordd' (with a G- prothetic) and Breton 'Horzh' (with a H- prothetic). They kept sheep, built hillforts and were among the few British tribes that resisted the Roman invasion, apparently organized by the Celtic leader Caratacus, exiled in their lands after his defeat (as the leader of the Catuvellauni) at the Battle of the Medway. Caratacus became a Roman public enemy, but was defeated (~51 AD) at the Battle of Caer Caradoc, by the Roman General Publius Ostorius Scapula. Caratacus fled north to the Brigantes, but their queen, Cartimandua, was loyal to the Romans and "handed him over in chains" to Ostorius, and he was dragged off to Rome to be presented to the Emperor Claudius. He made such an impression that he was pardoned and allowed to live in peace in Rome. After his liberation, according to the Roman historian Dio Cassius, Caratacus was so impressed by the city of Rome that he said:

- "And can you, then, who have got such possessions and so many of them, covet our poor tents?"

Around 70AD, the Ordovices rebelled again and provoked a somewhat excessive response by Agricola, who, according to the historian Tacitus, "exterminated the whole tribe". No other mention of the tribe appears in the historical records, but in view of the mountainous terrain of the lands of the Ordovices it is questionable whether Agricola could have wiped out the entire population.

The "Ordovician" geologic period was first described and named by Charles Lapworth in 1879 for rocks located in the lands of the Ordovices. The geology of the deep past shapes the land and gives rise to differences in ways of living that are often missed. As we shall see with the Dee, geological boundaries often become human borders. One of the great scientific disputes of the mid-nineteenth century concerned the partitioning of a large part of Wales into younger (Silurian) and older (Cambrian) rocks. It started in the 1830s with the work of two very different men, and the most important British geologists of the time. Revd Professor Adam Sedgwick was the man of genius, and R. I. Murchison, later Sir Roderick, was nothing if not the practical man of method. A 22 year-old Charles Darwin was one of Sedgwick's geology students in 1831, and accompanied him on a field trip to Wales that summer. The two kept up a correspondence while Darwin was on the Beagle expedition, and afterwards. However, Sedgwick never accepted the case for evolution made in "On the Origin of Species" in 1859. By the year 1839 Murchison had mapped and described the four groups that made up his Silurian System, defining each on the basis of fossils he had collected during five years fieldwork in South Wales and the Borders. His then friend Professor Sedgwick had given only a brief lithological description of the Cambrian rocks of North Wales by this date. As it became clear the two great divisions did not lie one on the other but overlapped at their boundary, Murchison extended his Silurian terminology into Sedgwick's domain. Arguments over the limits and validity of these two Systems scarcely abated with the death of the two chief contestants. British geologists remained in opposing camps until the end of the century, when Lapworth's Ordovician System of 1879 was generally accepted as a compromise for the disputed strata.

The Isles of Avalonia

In the Ordovician period, some 450 million years ago, the region that is today the source of the Dee lay under a semi-tropical sea well south of the equator: the Iapetus Ocean - Wales was in a location similar to that of present day Namibia. Present day Scotland was then part of the Laurentian continent (North America) on the further, northwestern, shore of Iapetus - possibly at the southern tip of what is now Greenland. Wales lay on the southeastern shore of the Iapetus ocean. Marine animals were abundant, including brachiopods which lived attached to or buried in the sea floor. Krakatoa-like volcanic activity was rife and Rhobell Fawr, just next to Dduallt, was producing vast quantities of hot ash which killed, buried and eventually fossilised these brachiopods.

The drift northwards would take the land through several different climatic zones: temperate, desert, equatorial, desert again and finally temperate once more. Ice ages would expose the rocks to polar extremes. At times the land would be above the sea, at other times below. Sometimes it would be landlocked, at other times coastal. These changing conditions would determine which rocks were formed and how fast they were eroded away.

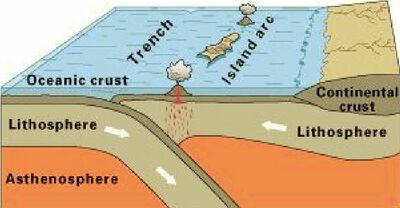

"Avalonia", located at the southern end of the Iapetus ocean, was an ancient microcontinent which now forms much of the older rocks of Western Europe, Atlantic Canada, and parts of the coastal United States. The name is derived from the Avalon Peninsula in Newfoundland and not directly from the Avalon of Arthurian legends.. The sinking floor of the Iapetus Ocean produced huge volumes of molten magma that erupted to make the backbone of Lleyn, Snowdonia, and Cadair Idris. The Ordovician came to a close (444-447 million years ago) in a series of extinction events that, taken together, comprise the second largest of the five major extinction events in Earth's history in terms of percentage of genera that went extinct (the only larger one was the Permian-Triassic extinction event). More than 60% of marine invertebrates died, including two-thirds of all brachiopod and bryozoan families.

The Iapetus Ocean closed by the end of the Silurian, about 425 million years ago, when Scotland and England, once on the opposite sides of the Iapetus Ocean, finally collided - the first step in the production of the supercontinent of "Pangaea". This Caledonian collision produced highlands covering most of Scotland and Wales. Eventually, with the break-up of Pangaea and the opening of the Atlantic ocean (along a slightly different line to that of the collision - leaving Scotland stuck to Europe rather than North America) the rocks of Avalonia were dispersed over a large portion of the Earth's surface. In the modern world, we see Avalonia as forming the basic structure of the Ardennes of Belgium and north-eastern France, north Germany, north-western Poland, England, Wales, south-eastern Ireland, the south-western edge of the Iberian Peninsula, the Avalon Peninsula, much of Nova Scotia, southern New Brunswick and parts of New England. In many of these regions slate is present as one of the principal rock types.

Inhabitants

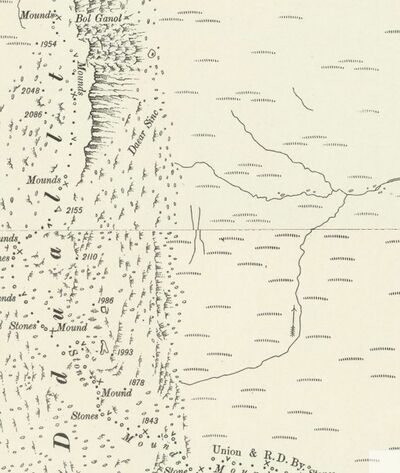

More than crows (of which more downstream), the area supports substantial populations of upland birds including raptors, such as the Hen Harrier (Circus cyaneus), Merlin (Falco columbarius), and Peregrine (Falco peregrinus). Evidence of activity in this area during the neolithic period between about 5000-2000BC is scarce, although there are large burial mounds that might be of neolithic date in the upper valley of the Dee, one of which at least, Tanycoed, is chambered. There are remains of ancient settlements close to the source of the Dee near Rhosdylluan and the modern A494 follows the course of a Roman road. It is here, where the road crosses the river on one of the Dee's many bridges that the stream starts to look like a real river. A little downstream is the village of Pandy, site of a fulling mill and a indication of the mills and industry to be found downriver. There is a large hillfort at Cefn Caer Euni.

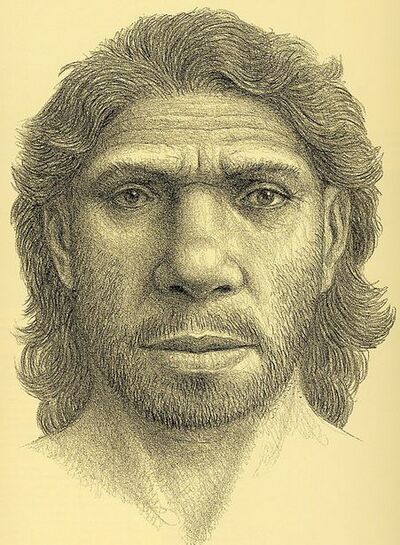

Just when people first settled the upper reaches of the Dee is not clear. Early Britons had to cope with extreme changes of climate, and at least seven times they apparently failed to do so and died out completely. The earliest evidence for humans (Boxgrove Man) in the UK dates from around 700,000 years ago, but that was in East Anglia. We know that subsequent glaciation drove mankind out of Britain around 475,000 years ago and that it was re-colonised around 400,000 years ago by Swanscombe Man (Homo heidelbergensis - believed to be the common ancestor of Neanderthals, Denisovans, and modern humans). Shortly after, the glaciers and ice-sheets returned again and mankind was absent for a further period.

Humans (for convenience "Human" includes Neanderthal as anatomically "modern" man only evolved some 130,000 years ago) returned around 325,000 years ago and possibly remained in Britain until around 200,000 years ago when the Ice Age entered another cold cycle. North Wales appears to have been home to Neanderthal people as this cold period began, but they were either killed-off or driven southwards by the cold. Their remains, the earliest Neanderthal remains in the UK and the furthest north west ever found, were unearthed in north Denbighshire at Bontnewydd in the Elwy Valley. Mankind remained out of Britain for over 100,000 years, only re-colonising the islands around 10,000 years ago. At that time the land would have been treeless tundra. The older view of Mesolithic Britons as being exclusively nomadic is now being replaced with a more complex picture of seasonal occupation or, in some cases, permanent occupation and attendant land and food source management where conditions permitted it. Juniper was the first tree to return after the ice departed, quickly followed by birch, hazel, pine, willow and alder. In the lowlands, oak, elm and pine dominated the landscape, while in the uplands pine and birch were more common. This heavily wooded landscape was home to red deer, roe deer, wild cattle and pigs, all of which were potential prey for Mesolithic hunters. The first forests were of birch, an arctic tree, pollinated by wind as it was still too cold for insects in Britain. By 7,500 BC, the rising sea levels caused by the melting glaciers caused Ireland to be separated from Britain and, by around 6500 to 6000 BC, the plains of Doggerland were submerged and the land-bridges to continental Europe were covered for the final time. It has been estimated the population of Britain (excluding Ireland) around 9000 BC to be 1,100–1,200 people, in 8000 BC to be 1,200–2,400, in 7000 BC to be 2,500–5,000, and in 5000 BC to be 2,750–5,500. According to some modern research, eighty per cent of the DNA of most white Britons, has been passed down from these few thousand individuals who hunted in this region after the last Ice Age. This would indicate a significance of the early migrants which dwarves all subsequent migrations to Britain from Europe such as the Saxons, Vikings and Normans. However other evidence suggests that migration, rather than cultural exchange was a more significant influence.

As for the Neanderthals, views of them have changed over the years. Neanderthals lived alongside early modern humans for at least part of their existence. We now know that some encounters (according to "The Guardian") were very intimate - some of us, outside of Africa, have inherited around 2% Neanderthal DNA. Interbreeding may have helped early modern humans coming out of Africa to adapt quickly to new environments, by acquiring genes from Neanderthals who had lived there for many thousands of years. Some of the DNA is found in parts of the human genome that are associated with skin and hair, maybe giving our ancestors thicker hair and skin that helped them cope better with the colder climate. Other DNA inherited from Neanderthals seems to be involved in boosting immunity, perhaps providing a quick fix against local infections.

The construction of the earliest earthwork sites in Prehistoric Britain began during the early Neolithic (c. 4400 BC – 3300 BC) in the form of long barrows used for communal burial and the first causewayed enclosures, sites which have parallels on the continent. The former may be derived from the long house although no long house villages have been found in Britain, only individual examples. The earliest evidence for farming in the British Isles comes from Ireland and probably the Isle of Man, and not from southern Britain. Elms grow on the edge of woodlands and are likely to be the first to be felled in a clearance. Nettles and plantains tend to flourish alongside human habitation. From 4000 BC to 3000 BC is a period when the elm tree had a great decline and remains of nettles and plantains show an increase. This is probably the first large scale impact of agriculture on the Wildwood. The area around Llangollen has been occupied since very early times. Before 6000BC any human presence would have been in the form of small bands of hunters. After this time it is known that a Neolithic farming culture, originating from Europe, was present in North Wales, although it is only after 3000BC that we have any direct evidence of the culture's presence in this area, in the form of many tumuli, cairns, stone circles and standing stones. The earliest surviving structures are the megalithic tombs which are found only in the Dee and Elwy valleys, with Tan y Coed, downstream at Cynwyd, being the "best preserved" example, even though it is described By the Royal Commission as follows:

- "An irregular elongated mound, much mutilated by the construction and opperation of Tan-y-Coed farm, c.43m by 14-20m and 4.0m high, thought to have originally been a circular mound, c.46m in diameter. There is a roughly square megalithic chamber within, its present entrance dating from re-use as a kennel, or store."

When the farm came up for sale, the estate agents described it as "Occupying a peaceful and idyllic rural location with remarkable panoramic views over open countryside, fields and mountains, Tyn-Y-Coed is a beautiful detached property which originally dates back to 1677." The fact that people had been burying their dead there five thousand years ago did not get a mention.

sources and links

- Geology of Rhobell Fawr;

- Cheshire Trove on geology;

- Dee Valley Archaeology;

Caer-Gai

Caer-Gai, a Roman fort on the banks of the Dee near Llanuwchllyn, was traditionally known as the home of Cei, the character in the Arthurian legend known in English as "Sir Kay". Legend holds that Arthur grew up and was educated here. The Caer-gai fort is square in plan, each side measuring about 420 feet (c.128m), and covers an area of 4½ acres. The fort was furnished with timber buildings never rebuilt in stone and was occupied from around 75AD until around 130. A spring which probably served the Roman soldiers lies about 200 feet outside the western corner-angle. The Roman name of the fort may have been "Lavobrinta". During the summer of 2001 archaeologists unearthed the central plank of a Roman barrel lid branded LEV at Chester which may have come from Caer-Gai. The "Kay" legend may actually have some truth at the base of it - a stone inscription from Llanfor refers to "Cavo(s) Seniargii (filius)" - Caw, son of Seniargus. Robert Vaughan of Hengwrt (1592-1666) recorded the discovery of an early Christian stone at Caer-gai itself with the inscription: "Hic Jacet Salvianus Burgo Cavi Filius Cupetiani" - and refers to the "fort of Cavi" ("Kay"?). A "vicus", or civilian settlement, is known to exist to the south and also possibly to the east of the fort, while again there is evidence to suggest that the site persisted as a centre of activity and cultural importance in the sub-Roman period. Edmund Spenser (1552–99) in The Faerie Queen, describes how the infant Arthur (109.4) was brought there:

- Vnto old Timon he me brought byliue, Old Timon, who in youthly yeares hath beene In warlike feates th'expertest man aliue, And is the wisest now on earth I weene; His dwelling is low in a valley greene, Vnder the foot of Rauran mossy hore, From whence the riuer Dee as siluer cleene His tombling billowes rolls with gentle rore: There all my dayes he traind me vp in vertuous lore

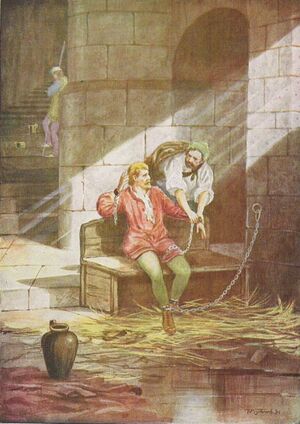

The earliest part of the fort is a rectangular turf rampart, much of the earthwork complex associated with the site is extant, and on the south-west side of the fort the rampart stands as a bank 8m wide. Both the south-east and south-west corners are very well-preserved, with the ditch curving around them. The bank is surmounted by a modern field wall, probably partly overlying the foundations of the original Roman stone wall that surrounded the whole area and incorporates a few of its squared stones. In addition to the civilian vicus, a variety of specifically military features were clustered around the fort, including a bathhouse, a parade ground and a possible mansio. A farm/manor house occupies the north corner of the fort and has destroyed most of the north corner-angle. Captain Rowland Vaughan, MP (c. 1590-1667), who was a notable poet and translator (he translated Latin and English books and hymns into Welsh) as well as a staunch Royalist, originally built the manor house in the late 16th -century, though the present structure is largely a product of post-Civil War rebuilding. In 1645 Vaughan and his Company fought at the battle of Naseby and in August of the same year Caer Gai was sacked and burned by General Myddleton's Roundhead troops. In March 1650 Vaughan was captured and imprisoned in Chester Castle for three years, during which time the house was burned down. Curiously William Vaughan, who attemped to found a colony at Avalon in Newfoundland (after which "Avalonia" is named) was related to Captain Roland. The name "Avalon" was given to the land by George Calvert who purchased the land from Vaughan (whose efforts to start a settlement there in 1617 and 1618 did not succeed) - in 1623 Calvert was given a Royal Charter granting the land the name "Province of Avalon": "in imitation of Old Avalon in Somersetshire wherein Glassenbury stands, the first fruits of Christianity in Britain as the other was in that party of America".

Llanuwchllyn

At Llanuwchllyn, the Dee is joined by the Lliw and the Twrch (means "wild boar" and gives some idea of the character of this river). The countryside hereabouts is eloquently and extensively described by George Bolam in his 1904 book "Wildlife in Wales". The village of Llanuwchllyn ("the village above the lake") is the headquarters of The Bala Railway (Rheilffordd Llyn Tegid) which runs for 7-kilometres (4.5 miles) along the lake's south east shore and was built on a section of the former Ruabon - Barmouth GWR route which was closed in 1965. Regular trains link the village with the town of Bala. At Llanuwchllyn, visitors can see the steam locomotives being serviced, can view the 1896-built Signal Box in operation and can visit the Station Buffet.

Gold was discovered here (at Carndochan, 52°51'40"N , 3°42'30"W) in the 1860s by a 12 year old boy, although many quartz boulders showing visible gold were scattered on the hillside and had apparently been missed. A company was formed in Manchester in 1863 to work the mine and operations between 1864-66 produced 1508 ounces of gold from 3158 tons of quartz. However, yields declined by 1866, and the plant was sold in 1876 following a winding-up order. Later revived, the mine worked on a small scale till 1905. Records show 12.5 ounces of gold from 50 tons of quartz in 1889, and 393 ounces of gold from 2638 tons of quartz between 1895-98. The deep adit, north-east of the mine from near the river, was completed about 1901. The metal occurs in a quartz-sulphide vein cutting Middle Ordovician volcanic rocks and its relationship to the mineralization in the nearby "Dolgellau Gold-belt" is the subject of continuing research. The National Waterfront Museum in Swansea houses a ceremonial cup made from gold extracted from the Carndochan mine in the 1860s. It is the largest object known to have ever been made from Welsh gold.

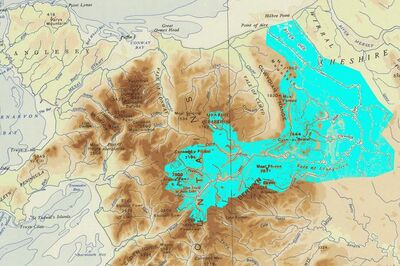

Bala Fault

The course of the river Dee here follows the line of the Bala fault - a major geological feature of north Wales. The fault is incredibly deep, and is thought to perhaps to extend down to the base of the earths crust so it can also be referred to as a "geofracture zone". It was this geofracture zone which allowed to emergence of magma during the Ordovician to form the volcanos at Rhobell Fawr, the Arans and Cader Idris. The fault is thought to have initially formed during the opening of the Iapetus Ocean in late Precambrian times (>541 million years ago) when Laurentia (North America) and Baltica (Europe) separated. As the Iapetus Ocean began to open tension cracks opened in a NE-SW direction parallel to the continental margins. These eventually became the Bala Valley, the Menai Straits and the valley at Church Stretton along the line of the A49. Between the Menai fault and the Stretton fault the land sank, forming the Welsh Basin with the Bala fault possibly forming an underwater escarpment.

The Bala fault is still "active" - on January 23rd 1974 there was a minor earthquake along it. The prominent "Earthquake lights" observed at the time of the shock possibly led to the local speculation that an aircraft had crashed, and search-and-rescue teams were deployed. Since nothing was discovered, it was concluded that a meteorite was responsible; more imaginative members of the public decided (and still believe) that a UFO had crashed. The scale of geological movements in the deep past can be seen near Llanuwchllyn where the two sides of the fault would have to be slid back for a distance of two miles to get the geology on either side to line up. The detailed cause of "Earthquake lights" has not been determined from among several different theories. One theory is that the stresses in the rocks, especially where quartz occurs (as it does in this region, c.f. the gold mines mentioned above) may lead to a "piezoelectric" effect such as that employed in guitar pick-ups, electric lighters and "quartz" watches. The "lights" are then caused by the high-votages generated.

The ancient river Dee was running before the last Ice Age and is thought to be about 3 million years old. As Wales plunged into the last Ice Age about 73,000 years ago, ice from the local ice sheets on the Aran and the Arenig Mountains flowed down the valley to Bala and along the Dee Valley and on to Cheshire. This ice formed glaciers and ice sheets that covered the landscape carving and shaping the landscape. The ice was up to a kilometre thick.

It is likely that the natural passage through the mountains formed by the Bala fault and the upper valley of the Dee was in use by travellers from Neolithic times. From the southern end of fault, near Barmouth, it would have been possible to trade with the mines at Llancynfelyn and Nant-Yr-Arian where fragments of charcoal in exposed spoil have been radiocarbon dated to the early Bronze Age, around 1400 BC.

sources and links

- Lippincott's Magazine or "Popular Literature and Science" October 1877;

- Caer Gai geophysical survey;

- Caer Gai at British Listed Buildings;

- Caer Gai Roman Site;

- Roman sites in NE Wales;

- The 1974 earthquake and the "lights";

- More on the same;

- More on the "Bala Fault";

- Colony of Avalon - who investigate, interpret, preserve and develop the archaeological remains of the colony.

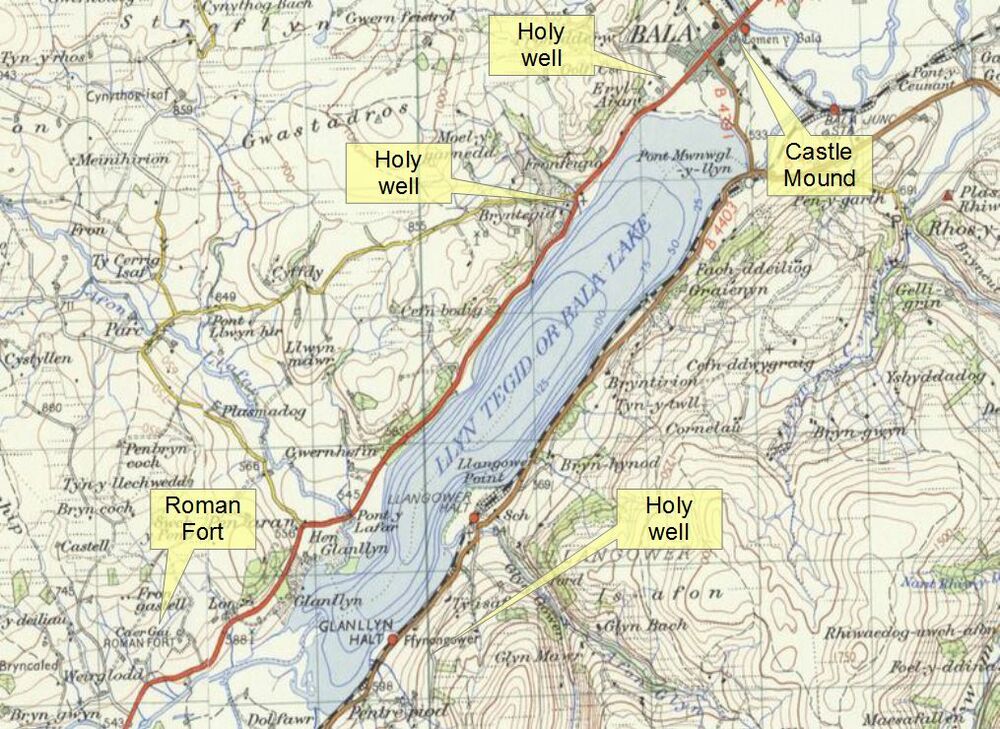

Map - Bala Lake

Bala Lake

- "Awaking occasionally in the night, I heard much storm and rain The following morning was gloomy and lowering. As it was Sunday I determined to pass the day at Bala and accordingly took my prayer book out of my satchel and also my single white shirt which I put on. Having dressed myself I went to the coffee room and sat down to breakfast. What a breakfast - pot of hare, ditto of trout, pot of prepared shrimps, dish of plain shrimps, tin of sardines, beautiful beef steak, eggs muffin, large loaf and butter - not forgetting capital tea. There's a breakfast for you." - George Borrow, Wild Wales: Its People, Language and Scenery.

The river broadens into Bala Lake (Llyn Tegid) - the largest (in terms of volume) natural body of water in Wales. "Y Bala" means "the outlet", describing the exit of the River Dee from Bala. The name of the lake in Welsh can be translated as "Lake of serenity". The predominant lowland rock type is sedimentary principally mudstone, siltstone and grit with some tuff (a rock formed from volcanic ash) and some limestone bands. Many of the upland areas are the result of volcanic action of the Aran Volcanic Group and the Rhobell Fawr Volcanic Complex. The Berwyn mountains were also influenced by volcanic action - Pistyll Rhaeadr often cited as the highest waterfall in Wales is the result of a river (Afon Disgynfa) flowing over a band of harder Silurian volcanic rock (Pistyll Rhaeadr is not a single drop, and both its single drop height and its total height are surpassed by both the Devil's Appendix and Pistyll y Llyn, as well as several other waterfalls).

There is a local legend (recorded by Gerald of Wales (c. 1146 – c. 1223) - who would believe anything he was told) that the waters of the Dee pass straight through the lake without mixing, but studies have shown that this is untrue. Michael Drayton (1563 – 23 December 1631) mentions both this feature and the outlet in his works:

- "The pearly Comvaye's head, as that of holy Dee, Renowned Rivers both, their rising have in me : So, Lavern and the Lue, themselves that head-long throw Into the spacious Lake, where Dee unmix'd doth flow. Trnicerriii takes his stream here from a native lin ; Which, out of Plmblemere when Dee himself doth win"

The Dee is not the only river to flow into Bala lake, there is also Afon Llafar and Afon Glyn.

The unique Gwyniad (Coregonus pennantii), a fish left over from the Ice Age, is found only in Llyn Tegid (the population is threatened by deteriorating water quality and by the ruffe, a fish introduced to the lake in the 1980s and now eating the eggs and fry of gwyniad - as a conservation measure, eggs of gwyniad were transferred to Llyn Arenig Fawr, a nearby lake, between 2003 and 2007.). Lake. The lake is also home to the rare Glutinous Snail. Perhaps the lake's most famous resident is "Teggie", the Welsh-dragon version of the "Loch Ness Monster". Though much looked for and even hunted by submarine, no trace of the "monster" has ever been found. Curiously, there is no mention of the monster prior to WW1, and this has led to speculation that the monster was the result of a devious experiment in the course of that war. The local semi-legend (of which there is no proof) states that an attempt was made to train "seals" to deliver explosive limet mines to enemy shipping and, rather than be blown-up, the animals chose to escape. Later sightings of the seals were believed to have led to the myth of the "monster".

As noted above, the Bala fault has not only directed the flow of the Dee, but also created a natural travel route through the mountains. The presence of three or more Roman forts down the valley, and the concentration of no less than four earthwork castles at the north end of the lake, emphasize the anxiety of rulers to control this area. "Bala castle" (Tomen Y Bala) is the largest of these earthwork castles and can be found in Bala itself. It is little more than a mound, but at 30 feet high it offers panoramic views across the town. Llywelyn the Great is believed to have commandeered Tomen Y Bala in the early 13th century before building the spectacularly situated stone castle Carndochan, not far from Llanuwchllyn. Carndochan Castle is now in ruins.

- "Finding myself rather dull in the inn I went out again notwithstanding that it rained. I ascended the toman or mound which I had visited on a former occasion. Nothing could be more desolate and dreary than the scene around. The woods were stript of their verdure and the hills were half shrouded in mist. How unlike was this scene to the smiling glorious prospect which had greeted my eyes a few months before. The rain coming down with redoubled violence I was soon glad to descend and regain the inn." - George Borrow, Wild Wales: Its People, Language and Scenery.

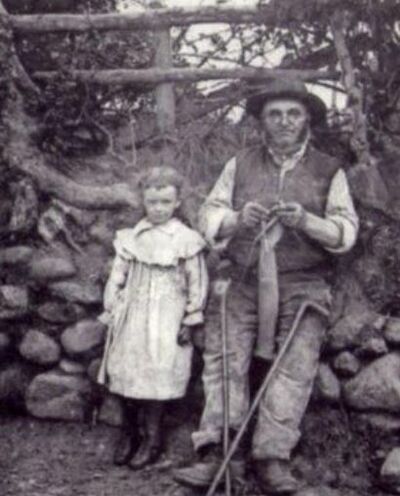

During the 18th-century, a hosiery industry developed which led to much rebuilding in the town and to an expansion of building beyond the extent of the medieval borough. Until the industrial revolution, Bala’s residents were famed for their knitting with wool products such as socks and Bala stockings bringing in a large percentage of the town’s revenue. In later life, George III always wore socks from Bala, which he claimed soothed his arthritis. Thomas Pennant in his "Tour Through Wales" describes Bala as follows:

- REACH Bala, a ſmall town in the pariſh of Llanyekil, noted for its vaſt trade in woollen ſtockings, and its great markets every Saturday morning, when from two to five hundred pounds worth are ſold each day, according to the demand. Round the place, women and children are in full employ, knitting along the roads; and mixed with them Herculean figures appear, aſſiſting their omphales [Page 68] in this effeminate employ. During winter the females, through love of ſociety, often aſſemble at one another's houſes to knit; ſit round a fire, and liſten to ſome old tale, or to ſome antient ſong, or the ſound of a harp; and this is called Cymmorth Gwau, or, the knitting aſſembly. MUCH of the wool is bought at the great fairs at Llanrwſt, in Denbighſhire. CLOSE to the ſouth-eaſt end of the town, is a great artificial mount, called Tommen y Bala, in the ſummer time uſually covered in a pictureſque manner with knitters, of both ſexes, and all ages. From the ſummit is a fine view of Llyn-tegid, and the adjacent mountains. On the right appear the two Arennigs, Vawr and Vach; beyond the farther end, ſoar the lofty Arans, with their two heads, Aran Mowddwy and Penllyn; and beyond all, the great Cader Idris cloſes the view. THIS mount appears to have been Roman, and placed here, with a caſtelet on its ſummit, to ſecure the paſs towards the ſea, and keep our mountaneers in ſubjection. The Welſh, in after time, took advantage of this, as well as other works of the ſame nature. THE town is of a very regular form: the principal ſtreet very ſpacious, and the leſſer fall into it at right angles. I will not deny, but that its origin might have been Roman.

Pennant is wrong about the "Roman street plan" - around 1310, in a move intended to quell the rebellious local community, Bala was given its Royal Charter by Roger De Mortimer of Chirk Castle and the current street plan dates back to this time. By 1310 Roger Mortimer had laid out 53 "burgages" - plots of land for building:

- ‘for the king’s benefit for the security of those parts and to restrain the malice of evil-doers and robbers in the locality’.

Mary Jones

In 1804 Mary Jones aged 15, walked barefoot along the Bala fault from Llanfihangel-y-Pennant to Bala to buy a Bible from Thomas Charles – a journey of over 50 miles there and back. It was not the distance that was impressive, or even the fact that she walked barefoot, but the fact that she had saved the seventeen shillings (over six years) to buy the book. Unfortunately Charles, had none left. However (according to one version of the story) he took pity on Mary and gave her his own. It is said that Mary Jones’s visit to Thomas Charles made such an impression upon him that he had "no peace of mind" until he had found a way to ensure a regular supply of cheap Bibles for the common people of Wales. In 1800, Charles seemed to be worrying about everything: a frost-bitten thumb gave him "great pain and much fear for his life", his friend, Rev. Philip Oliver of Chester, died, leaving him director and one of three trustees over his chapel at Boughton in Chester and this "added much to his anxiety". In the 19th Century there was a whisky distillery at Frongoch near Bala. Unfortunately, for the Welsh whisky industry, this distillery closed in the later years of the 19th Century. Its closure coincided with the height of religious revival and “chapel building mania” in Wales, which stressed the importance of temperance.

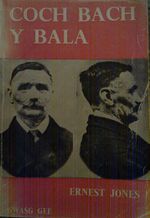

Coch Bach y Bala (the "Little Redhead of Bala) was more properly John Jones, otherwise known as ‘The Welsh Houdini’ best known for his poaching and persistent thievery, both of which brought him into regular and continuous trouble with the Law and for his frequent jail escapes. Jones’s first escape from prison was in November 1879, when he was awaiting trial at Ruthin Gaol, for stealing 15 watches at Bala and Llanfor. Despite his frequent escapes, John Jones spent more than half his life in prison, with over 10 separate convictions for theft, breaking and entering, and on one occasion, for "rioting against the Police" in Bala. Jones’s activities caught the public’s imagination, and the media of the time sensationalised and publicised his activities. Jones was on the run for six days after his final escape (on 30 September 1913 he tunnelled out of his cell and using a rope made out of his bedding he climbed over the roof of the chapel and kitchen and got over the wall) before being tracked down on the Nantclwyd Estate several miles from Ruthin. He was shot in the groin by one of his pursuers, 19 year old Oxford undergraduate Reginald Jones-Bateman, son of an increasingly unpopular local landowner. John Jones was 60 years old, was living off tallow candles and methylated spirits, and died of shock and haemorrhaging due to his injury (a double shotgun wound). Jones-Bateman was charged with manslaughter, though the charges were subsequently dropped. Despite his wrongdoings, John Jones was a popular figure and the circumstances surrounding his death were the source of much public discontent in the area. Postcards that showed a photograph of his funeral, and the location where he was shot, were mass-produced and sold. Maybe not so much as a ‘memento mori’, but as the final evidence, legitimised by the camera, that ‘Coch Bach’ was finally confined to one place. Jones-Bateman became an unpopular captain in the 3rd Welsh Regiment and battalion "bombing officer". Bombing Officers were unpopular anyway - opposing forces in WW1 frequently maintained a tacit live-and-let-live "truce" in which they refrained from bomb-throwing between trenches. Bombing Officers would try to encourage the troops to throw bombs (grenades) over to the enemy side and this could spark-off a end to the quiet life that those in some parts of the trenches preferred. Jones-Bateman was severely wounded in a grenade "accident" in France (July 1916) and invalided home. He later went off to Ceylon, where he wrote a book on his amataur archeological exploits ("A Refuge from Civilisation") and a guide to playing Bridge.

The Lake

Bala lake has always been prone to flooding. There is an ages-old belief in the countryside that Bala will continue to grow bigger until it has swallowed up the village of Llanfor (site of another Roman fort), now about a couple of miles from the water's edge. There is a Welsh couplet, still well known in Merionethshire, which, translated into English, runs:

- "Bala old the lake has had, and Bala new: The lake will have, and Llanfor, too."

According to legend the site of the original town was near the middle of the present lake, at a spot opposite Llangower. There, a peaceful community lived a happy, prosperous life in houses clustering around a well called Ffynnon Gwyer, or "Gower's Well" (note the connection with Gwyn/Gwen and "Gwyniad"). Only one very important thing had these people to remember: that was to cover up their well every night, otherwise, the spirit of the well would grow angry. One night, after much drinking, the guardian of the well forgot his task and the well began to gush forth water. The guardian fled, though it is said the angry waters overtook him and drowned him miserably. When morning broke, instead of fields and houses, the valley contained a great lake three miles long and a mile wide. It is also claimed that on moonlit nights towers and buildings can be seen under the waters of Bala Lake. A further legend states these buildings to be the palace of King Tegid, husband of Ceridwen, the mother of the legendary Welsh bard Taliesin. In this version of the legend the king refused to listen to the warnings of a harpist as regards a coming flood, which promptly drowned him, and his palace. "King Tegid" is an obvious reference to Tylwyth Teg, a common Welsh name for fairies. Almost exactly the same tale is told of Llyn Llech Owen ("the lake of Owain's slab") in Carmarthenshire.

Unfortunately, Bala lake was actually formed by glacial action, but even in comparatively recent times Llyn Tegid has flooded dangerously, especially when whipped up by a south-westerly wind. The 18th century traveller Reverend W Bingley noted, in his accounts of his college vacation of 1798, that the lake was subject to ‘dreadful’ overflowings, while other sources record a massive torrent in the early 1780s, when the floods rushed over the Vale of Edeirnion to the south, killing several people. The Welsh lawyer Richard Fenton described the catastrophe in Archaeologia Cambrensis (1813):

- "The Lake of Bala was covered with the wreck of different houses, and one person recovered two feather beds floating on the lake, and one with a looking glass on it as she had left it when she left her house".

Alfred Tennyson also mentions the Dee floods at Bala in his Idylls of the King, using it as a Victorian sexual metaphor for the relationship between Geraint and Enid:

- "And Enid tended on him there; and there Her constant motion round him, and the breath Of her sweet tendance hovering over him, Filled all the genial courses of his blood With deeper and with ever deeper love, As the south-west that blowing Bala lake Fills all the sacred Dee."

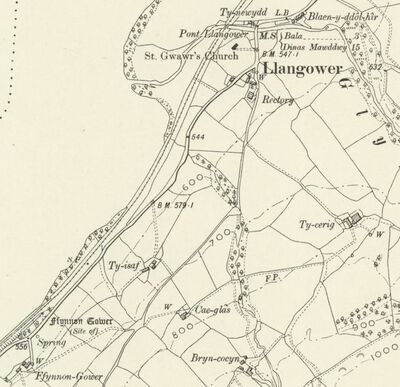

Another "Ffynnon Gwyer", said to be named after St Cywair who dwelt at Llangywer in the 5th or 6th century, is a "holy" well on the east side of the lake. St Cywair (or Gwyr), a 5th century Irish princess, is said to have married king Coel Godhibog of the north Britains. She is reputed to have been the mother of Llywarch Hen, the early Welsh bard, and St Pabo. Ffynnon Gower is sited some 650m south-west of St Cywair's church and while said to be a "cure-all" is often dried up. The Royal Commission on Ancient Monuments casts some doubt as to whether this is actually the original well associated with the church.

Apart from "Ffynnon Gwyer" there are several other "holy" wells around Bala Lake. "Ffynnon Beuno" in Bala was said to be good for ligaments and bones, for eyes and for the liver, kidneys and bowels depending on whether you bathed in it or drank it. Its fame lasted into the Victorian era when Richard Lloyd Price of Rhiwlas, on whose estate it then lay, jumped into the burgeoning health spas market, bottling and selling "St Beuno’s Table Waters, efficacious for the kidneys" from the old Workhouse Building on the High Street in Bala. By the 1980's the well was in a sorry state - filled in with builders rubble. In the early 2000's it was excavated to reveal what matched a record from 1913:

- "... rising in a sunken rectangular enclosure of stone, 12 feet by 9 feet with six steps at one corner. The water is fairly deep and the overflow is copious; where it crossed the main road the roadway was roughly paved, hence the name ‘Pensarn Road.’ There are no traces of buildings over or immediately around the well. The hilly district to the south-west is called Bronydd Beuno."

Unfortunately, health and safety concerns meant that the well could not be left as an open body of water so it was filled in with stones, although its outline is still marked with a low wall. It seems odd that there should be such health and safety concerns given that the largest natural lake in Wales is only a very short walk away.

St Buenos Church at Llanycil on the west shore of Bala Lake (where the Bible Society has its "Mary Jones World Visitor Centre") was also said to have a Holy Well - another Ffynnon Bueno, but no sign of this remains. The well may have been mineralised, as just up the hill at Fron Feuno there is a disused quarry where a bedded deposit of manganese ore (psilomelane) was worked. Manganese is found in leafy green vegetables, fruits, nuts, cinnamon and whole grains. A deficiency of manganese causes skeletal deformation in animals and inhibits the production of collagen in wound healing and this can be caused by chronic liver or gallbladder disorders - while this could explain the "holy" properties of the wells hereabouts, manganese is toxic at high levels and most people obtain enough from dietary sources.

Craig-y-Fron, just outside Bala to the north-west, provided stone for many buildings in Bala, including Coleg-y-Bala and Bodiwan. The excavations have left a 400m cavern with the roof supported by regular pillars of rock, known locally as “the caves”. The rock type is tuff (a rock formed from volcanic ash), sandwiched between mudstone (above) and siltstone (below). The internal roof (mudstone) has ripples - indicating sedimentary rock. On the east side of Bala Lake, the area was known as Bryniau Golau (The "Lit-up Hills") derived from the fires of lime-kilns lighting up the area at night. The remains of several lime-kilns and a small limestone quarry are still visible over the ridge to the East.

sources and links

- The Mary Jones walk;

- Ffynnon Beuno from "Well-hopper";

- An Inventory of the Ancient Monuments in Wales and Monmouthshire: VI - County of Merioneth;

- "Visit Bala";

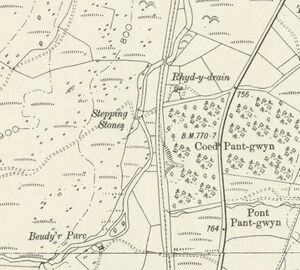

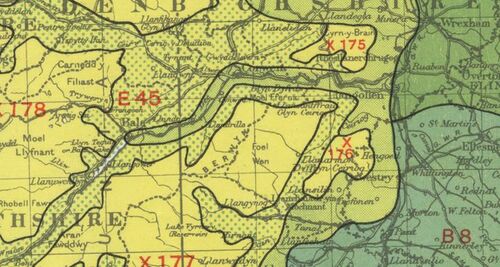

Map - Bala to Crogen

Below Bala

.

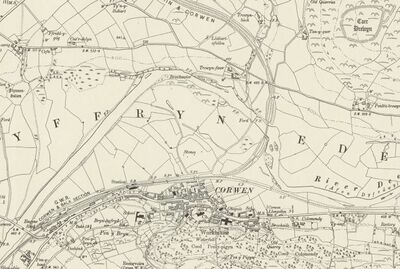

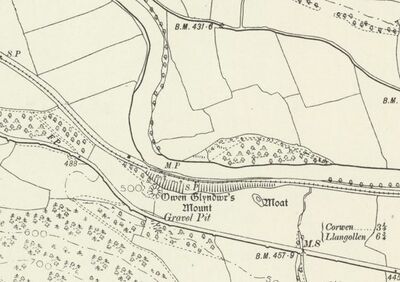

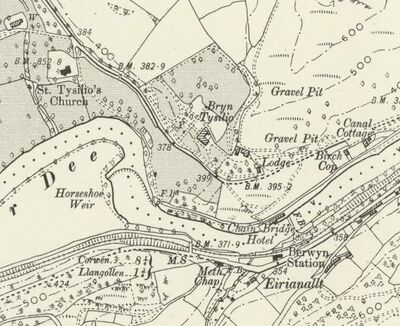

To the geological and the human themes we now add a third, the industrial. Thomas Telford constructed sluices at the outlet of Bala Lake to control the flow downstream so that there was always sufficient to supply the Llangollen Canal which starts at Horseshoe Falls. The Llangollen navigable feeder became the primary water source from the River Dee for the central section of the incomplete Ellesmere Canal. Somewhere around the site of the sluices was a motte which has now vanished, one of several in the neighborhood. Pen uchar'r llan Scheduled Ancient Monument earthwork is an oval ringwork enclosure which dominates the northern end of Llanfor. It has been identified as one of a pair of earthworks, the other being Tomen-y-castell (NPRN 406424), located some 1.25km to the north-east. A footpath is depicted on historic (1889) Ordnance Survey mapping, which would have connected Tomen-y-castell to the northern end of Llanfor, and may represent a historic route. Pen uchar'r llan has been identified as a possible medieval commotal structure.

Afon Tryweryn

Just below Bala the Dee is joined by the Hirnant and, roughly half a mile downstream from Bala Lake, the 12-mile long River Tryweryn, flowing down from Llyn Celyn, created in 1965 to provide water for Liverpool. In the late 1950s the Bala Lake Scheme was promoted to increase the available water for abstraction in the River Dee. Telford's original sluices were by-passed and the natural lake outlet was lowered . New sluice gates were constructed downstream of the confluence with the Tryweryn, Construction of the Celyn reservoir in the 1960's involved inundation of the village of Capel Celyn and adjacent farmland, which was controversial, especially as the village was a strong-hold of Welsh culture and the Welsh language, whilst the reservoir was being built to supply Liverpool and parts of the Wirral, rather than Wales. The legislation enabling the development was passed despite the opposition of 35 out of 36 Welsh Members of Parliament (with the 36th not voting). At that time, the 67 inhabitants of the village of Capel Celyn were forcibly removed as the village. This led to an increase in support for the Welsh Nationalist party and Welsh devolution. The abstraction sites downstream include one at Huntington water treatment works Chester operated by United Utilities, which supplies water to Liverpool and Wirral. The building of the reservoir also contributed to the final closure of the GWR branch line from Bala to Blaenau Ffestiniog. Passenger trains had ceased running in 1960, and the last freight train ran in 1961. The line was subsequently flooded by the lake, and the base of the dam also crosses it.

Below Bala Lake

Below Bala Lake the Dee valley supports sheep and cattle grazing and the production of hay and silage. This area may have been farmed since the Neolithic, as the flow of the river would have been sufficient to undermine trees during its frequent changes in course. These glacial and periglacial deposits are rapidly eroded during storm events giving rise to a considerable load of sediment moving downstream. A large sub-circular enclosure has been identified on the flood plain of the Dee, at Ty-tandderwen, just east of Llyn Tegid, from aerial photographs and geophysical survey, and this seems likely to be a neolithic settlement or ceremonial enclosure (or possibly even a mediaeval cattle enclosure).

It is thought that Llanfor was once the commote centre of Penllyn, before it was superseded by Bala sometime before the thirteenth century. The customs and tolls of the market and fair of Llanfor were transfered to the new foundation of Bala in 1310-1311. The earthwork overlooks the church from an elevated position some 70m north. The two may have been contemporary and have formed elements of the same settlement. The earthwork is defined by a massive rampart, up to 5.2m high, with traces of an external ditch. The area enclosed measures some 26m by 18m. At Llanfor, yet another "Holy Well" is depicted on historic (1889-1901) Ordnance Survey mapping. The well is associated with the church of Saint Tyneio, the 6th century Patron Saint of the town. The following legend is told of the church:

- "Llanfor Spirit troubled the neighbourhood of Bala, but he was particularly objectionable and annoying to the inhabitants of Llanfor, for he had taken possession of their Church. At last, the people were determined to get rid of him altogether, but they must procure a mare for this purpose, which they did. A man riding on the mare entered the Church with a friend, to exorcise the Spirit. After some time this man emerged from the Church with the Devil seated behind him on the pillion. An old woman who saw them cried out, “Duw anwyl! Mochyn yn yr Eglwys”—“Good God! A pig in the Church.” On hearing these words the pig became exceedingly fierce, because the silence had been broken and also because God’s name had been used. In his anger he snatched up both the man and the mare and threw them right over the Church to the other side, and there is a mark to this day on a grave stone of the horse’s hoof on the spot where she hit. But the Spirit’s anger was all in vain, for he was carried by the mare to the river and laid in Llyn-y-Geulan-Goch. But so much did the poor animal perspire whilst carrying him, that, although the distance was only a quarter of a mile, she lost all her hair."

Elias Owen, in his 'Welsh Folk-lore' (1887) quotes both this and several other slightly different version of the story, where, for example, the impression of the horse-hoof is on the river-bank instead. Owen concludes:

- "There is a good deal that is human about these stories when stripped of the marvellous, which surrounds them, and it is not unreasonable to ask whether they had, or had not, a foundation in fact, or whether they were solely the creations of an imaginative people. It is not, at least, improbable that these ghostly stories had, in long distant pre-historic times, their origin in fact, and that they have reached our days with glosses received from the intervening ages. They seem to imply that, in ancient times, there was deadly antagonism between one form of Pagan worship and another, and, although it is but dimly hinted, it would appear that fire was the emblem or the god of one party, and water the god of the other; and that the water worshippers prevailed and destroyed the image, or laid the priest, of the vanquished deity in a pool, and took possession of his sacred enclosures."

On the floodplain of the Dee, to the east of Bala and to the south of Lanfor, is a remarkable series of early Roman sites. These have been ploughed completely flat and survive only as cropmarks, discovered by Cambridge University photographers in 1975. The earliest site is a very large marching camp beyond which can be seen one corner of the triple ditch system of an auxiliary fort. The most prominent feature is a double-ditched polygonal enclosure. The fort is roughly square, with sides running 650 feet along an east-west axis, and 600 feet north to south, enclosing an area of about 9 acres. The site is defended by a rampart and 3 ditches on all sides. The ramparts appear to have been made of simple turf walls. Within the walls are signs of two colonnaded courtyard buildings, set in the centre of the fort. These were probably the principia (the administration building) and praetorium, or general's quarters. To the south stood a granary, and a series of 22 subdivided buildings suggest several barracks. The barracks are larger than usual, at 10m by 60m. The number and size of the barracks suggest that Llanfor was made to hold 4 legionary cohorts. The fort was probably built around 70 AD and was in use for only a short period before it was replaced by a new fort at Caer Gai, 5 miles distant, about 75 AD.

Rhiwaedog, or "The Bloody Brow" was, according to a local tale, the site of a battle between "Llywarch Hên" and the Saxons. There is a historical record of a stone circle, Pabell Llywarch Hen ('The tent of Llywarch the Old'), close to Llanfor, but the circle was unfortunately removed in the 17th century during "agricultural improvement". Llywarch Hen was a 6th-century prince and poet of the Brythonic kingdom of Rheged, a ruling family in the Hen Ogledd or "Old North" of Britain (modern southern Scotland and northern England). Along with Taliesin, Aneirin, and Myrddin, he is held to be one of the four great bards of early Welsh poetry. Whether he actually wrote the poems attributed to him is unknown, and most of what is known about his life is derived from early medieval poems which may or may not be historically accurate. The Bonedd lists his date of birth c. 534, and his death c. 608, meaning he would have been around 80 years old at the time of his death, in keeping with his reputation as Llywarch "the old." However, some sources list different birth and death dates, with unlikely claims of his age reaching 105, or even 150 years. George Borrow writes of him as follows:

- "Llewarch Hen or Llewarch the Aged was born about the commencement of the sixth and died about the middle of the seventh century having attained to the prodigious age of one hundred and forty or fifty years which is perhaps the lot of about forty individuals in the course of a millennium. If he was remarkable for the number of his years he was no less so for the number of his misfortunes. He was one of the princes of the Cumbrian Britons but Cumbria was invaded by the Saxons and a scene of horrid war ensued. Llewarch and his sons of whom he had twenty four put themselves at the head of their forces and in conjunction with the other Cumbrian princes made a brave but fruitless opposition to the invaders. Most of his sons were slain and he himself with the remainder sought shelter in Powys in the hall of Cynddylan its prince. But the Saxon bills and bows found their way to Powys too. Cynddylan was slain and with him the last of the sons of Llewarch who reft of his protector retired to a hut by the side of the lake of Bala where he lived the life of a recluse and composed elegies on his sons and slaughtered friends and on his old age all of which abound with so much simplicity and pathos that the heart of him must be hard indeed who can read them unmoved. Whilst a prince he was revered for his wisdom and equity and he is said in one of the historical triads to have been one of the three consulting warriors of Arthur " - George Borrow, Wild Wales: Its People, Language and Scenery.

Llandderfel

Downstream of Llanfor the Dee valley narrows to a point where the river and the railway could not both pass through, so the railway uses a short tunnel to pass the bottleneck, After this the Valley broadens again around Llandderfel and is joined from the south by the valley of the river Callettwr.

Near Llandderfel was Ffynnon Derfel - a spring attributed to the 6th Century Saint, Derfel. Derfel is said to have had healing powers where animals were concerned, and in particular, for cattle. Visiting the well in 1913, the Royal Commission inspector described it as follows:

- "There is no well at the present time at the spot where the water gushes forth in which adult bathing could have taken place or to which vaticinatory offerings could have been made; there is merely a stone slab about two feet long, which, with some rude masonry, protects the spring and forms a small reservoir> about four feet wide. The water escapes at one side of the stone, and runs along the east side of the field."

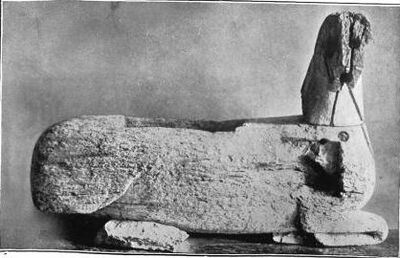

In the porch of Llandderfel church there still survives the mutilated figure of an animal lying down, with its legs tucked neatly beneath its body. Some believe it to be a stag, others a horse. It still exhibits faint traces of red paint. With the animal is a substantial portion of a decorated wooded pole. For ages these have been known as the "cefifri and ifon" of St Derfel (his horse and staff or walking-stick). However a letter to the bishop written 8 November 1626, when the image was more complete, records the presence of "a wooden image of a Redd Stagg as a relique of the image of Dervell Cadarn" on the north side of the sanctuary, which is probably where the cult image stood before the Reformation. Damage to the stag began when in 1730 the Rural Dean ordered that the image be decapitated. At the same period, the image was carried in procession to Bryn Sant the "saint's hill", also called Bryn Derfel, annually on Easter Tuesday, where it was made to function as a sort of fairground ride; resulting in yet further damage. This was once accompanied by a statue of Derfel which befell an even stranger fate. On 6 April 1538 Thomas Cromwell's Commissary for the St Asaph diocese, Ellis Price, wrote to his master:

- ..there is an image of Darvel gadarn within the saide diosece, in whome the people have so greate confidence, hope, and truste, that they cumme dayly a pilgramage unto hym, somme with kyne, other with oxen or horsis, and the reste withe money: in so muche that there was fyve or syxe hundrethe pilgrames, to a mans estimacion, that offered to the saide Image the fifte daie of this presente monethe of Aprill. The innocente people hathe ben sore alured and entised to worshipe the saide Image, in so muche that there is a commyn sayinge as yet amongist them, that who so ever will offer anie thinge to the saide Image of Darvellgadarn, he hathe power to fatche hym or them that so offers oute of Hell when they be dampned.

Cromwell ordered that this statue be confiscated, and taken to London for destruction, and a further letter from Price, dated 28 April, records not only that this had been done, but that such was the local regard for St Derfel's image:

- ..the person [parson] and the parysheners of the churche wherein the saide Ymage of Dervell stode, profered me fortie powndes that the said Ymage shulde not be convaide to London..

- and warned Cromwell that the parish priest "wythe others" were heading for London to demand the return of their sacred image, and to complain about Price's conduct. Even if they reached London in time, their complaints were of no avail, the image was burned at Smithfield on 22 May 1538 together with John Forest, a Franciscan friar, and the only Catholic martyr to be burned at the stake.

Thomas Pennant in his "Tour Through Wales" tells the story as follows:

- "A LITTLE beyond the extremity of this romantic part, in an opening on the right, ſtand the church and village of Llan-Dderfel: the firſt was dedicated to St. Derfel Gadarn, and was remarkable for a vaſt wooden image of the ſaint, the ſubject of much ſuperſtition in ancient times. The Welſh had a prophecy, that it ſhould ſet a whole foreſt on fire. Whether to complete it, or whether to take away from the people the cauſe of idolatry, I cannot ſay; but it was brought to London in the year 1538, and was uſed as part of the fuel which conſumed poor frier Foreſt to aſhes, in Smithfield, for denying the king's ſupremacy. This unhappy man was hanged in chains round his middle to a gallows, over which was placed this inſcription, alluſive to our image: "David Darvel Gutheren, As ſayth the Welſhman, Fetched outlawes out of Hell. Now is he come with ſpere and ſheld, In harnes to burne in Smithfeld, For in Wales he may not dwel. And Foreeſt the freer. That obſtinate lyer, That wylfully ſhal be dead. In his contumacye, The goſpel doeth deny, The kyng to be ſupreme heade.". THE prophecy was fulfilled, the image burnt, and the Foreſt conſumed, to the great content of the lord mayor, the dukes of Suffolk and Norfolk, the lord admiral, and lord privy ſeal, and divers others of the nobility, who honored this auto de fe with their preſence†; but unfortunately, the frier not having the inſenſibility of our wooden ſaint, on the touch of the flames ſhewed the natural horrors at approach of an agonizing death, and payed very little reſpect to the arguments of the pious Latimer, who was placed oppoſite to the ſufferer, in a pulpit, to preach him into a ſenſe of the crime of differing in opinion with his ſovereign in religious matters; for which the prelate himſelf ſuffered in a ſucceeding reign. Foreſt thought fit to deny that Henry was head of the church; and Latimer would force that honor upon Mary, who choſe to cede it to the Pope."

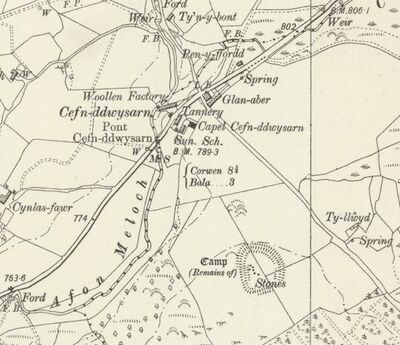

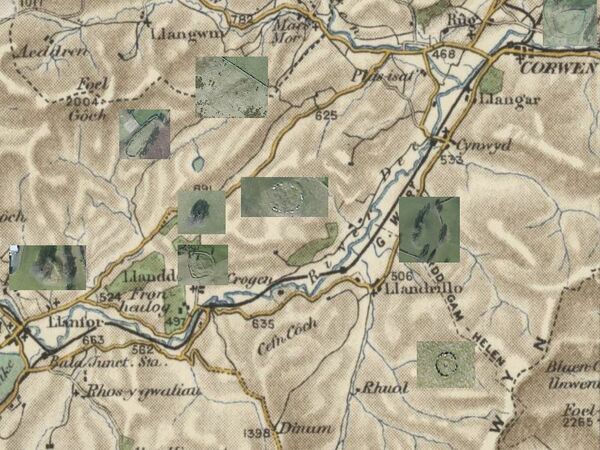

The valley of the River Dee between Bala and Corwen is filled with earthworks, stone-circles and other prehistoric remains. Unfortunately, many have been the subject of "robbing", and some have been completely destroyed, often by "agricultural improvement". Many of the sites will be disappointing to those expecting a "stonehenge". At Cefnddwysarn there is a sizeable enclosure not using a naturally good defensive location but with a double wall (bivallate), so clearly not just a settlement or stock enclosure. The inner rampart was apparently unfinished. There is a much larger hillfort at Cefn Caer Euni. This is a strongly-defended bivallate fort with evidence of numerous houses and probable extension and refortification. This fort, significantly, overlooks the major route between the coast and inland that was eventually taken by a Roman road, rather than overlooking the Dee Valley, and the river crossing at the east end of Bala Lake was clearly an important point on this route. That, and the proximity of the hillfort, may have influenced the siting of the early Roman fort at Llanfor.

sources and links

- Cefnddwysarn - remains of camp;

- Legends of Rhiwaedog;

- Derfel and his well;

- Llanfor Roman Cap at Britain Express;

- Llanfor Roman Cap at Snowdonia National Park Authority website;

- Llanfor "Holy Well";

- The Archaeology of the Welsh Uplands - edited by David M. Browne, Stephen Hughes

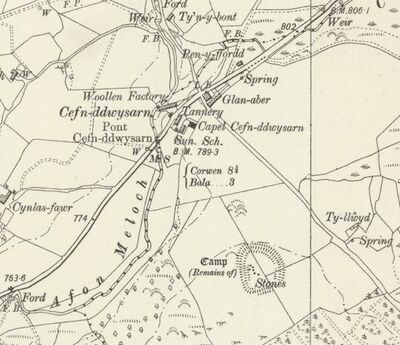

Map - Llandrillo and Cynwyd

Llandrillo

Here we find St Trillo's well - "An Inventory of the Ancient Monuments in Wales and Monmouthshire" states that:

- "This spring, which is situated about 500 yards north of the parish, is now dry except in winter or very wet weather. No local traditions relating to it exist, and it does not appear to have possessed healing properties or been used for divination - visited 12th July 1913."

Trillo was nobly born, in Brittany, and came to Wales as a disciple and student of Saint Cadfan (the 6th century founder-abbot of Tywyn and Bardsey), who later admitted Trillo to the religious life. St Trillo's Church stands on a mound next to the Ceidiog stream close to its confluence with the River Dee. Geochemical studies have shown anomalously high levels of a large group of metals (Titanium, Zinc, Iron, Manganese) in streams draining the Carnedd y Ci area south of Llandrillo. In fact there is a legend associated with the well, that it "sulkily migrated sfter an insult". The church contains an inscribed stone: a granite slab, 0.7m by 0.6m by 0.5m, bearing "a possible inscription", currently illegible, and said to be Roman, but which look very much like runes. The stone was "originally" at Blaen-y-Cwm, some miles to the south at the head of Cwm Pennant.

Here the flood-plain of the Dee broadens until it is about a mile wide. Above the Ceidiog valley - Cwm Pennant, to the west are numerous cairns and a rather well defended circular hillfort. Cwm Pennant eventually leads to a pass over into Cwm Rhiwarth and the Tanat valley. This sheltered vale, over three miles long, probably has been used for agriculture and permanent settlement throughout history.

At Tyfos, half way between Cynwyd and Llandrillo, stands a "stone circle" some 50yds in diameter with thirteen to twenty stones (depending on what you count) each standing just one or two feet tall. This may be the remains of a cairn or barrow in which the stones formed a "kerb" around the outside, rather than a true "Stonehenge" type of monument.

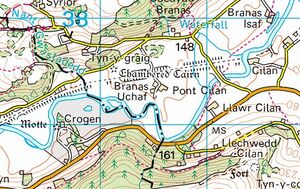

In just a six kilometer stretch of the Dee valley are the circles of Tyfos Uchaf and Moel ty Uchaf, and the remains of three chambered tombs including that of Branas Uchaf chambered cairn. The chamber remains at Branas Uchaf consist of two large erect aligned slabs and several smaller stones which together seem to form a "passageway". Moel ty Uchaf, dating from around 2,200 BC, is said to be aligned on the Midsummer rising of the star Deneb in Cygnus - similar to the circle at Grey Croft near the site of the former nuclear-power stations at Sellafield, Cumbria. Moel Ty Uchaf is an unusual site (here is how to get there) which may have had both a burial and ritual function. Although it has the appearance of a stone circle, there are also similarities to the kerbs surrounding some of the upland burial cairns, and the central mound may once have covered a burial. The same arrangement, Deneb alignment, ring and central burial, was found at Grey Croft stone circle - also dated to around 2200 BC.

An ancient trackway known as "Ffordd Gam Elin" runs from the earthworks at Caer Bont to the cairn/circle on the summit of Cader Bronwen, passing a further and more spectacular stone circle of Moel ty Uchaf on the way. A round funerary cairn, 23m in diameter and 1.6m high, surmounted by a small recent cairn sits on top of Cader Bronwen. 9m to the SSW is a large natural boulder, 3.0m by 2.0m by 1.1m high, set on the county border. The name 'Arthur's Table' (Bwrdo Arthur) attaches to either cairn or stone. "Ffordd Gam Elin" is a clear reference to St "Elen of the Hosts" a legendary builder of Roman Roads in Wales. The road heads in the general direction of Viroconium (Wroxeter) probably via the copper mines which lie along its direction. In the other direction, to the north, the trackway may have led to the Great Orme copper mines. Large-scale human activity on the Great Orme began in Bronze Age (around 2000 BC) with the opening of several copper mines - about the same time as Stonehenge was being built. These were abandoned around 600 BC shortly after the start of the Iron Age.

Thomas Pennant in his "Tour Through Wales" describes the then quite prominent earthworks at Caer Bont as follows:

- "PURSUE the journey to Bala. Go by the little church of Llangar. Obſerve ſomewhat farther on the left, in a field called Caer Bont, a ſmall circular entrenchment, conſiſting of a foſs and rampart, with two entrances, meant probably as a guard to this paſs. My fellow-traveller, the reverend Mr. Lloyd, informed me, that in another tour he had aſcended a hill, above this place, called Y Foel, on whoſe ſummit was a circular coronet, of rude pebbly ſtones, none above three feet in height; with an entrance to the eaſt, or riſing ſun. The diameter of the circle is ten yards. Within was a circular cell, about ſix feet in diameter, ſunk a very little below the ſurface; and about a hundred yards diſtance, facing this, are the reliques of a great Carnedd, ſurrounded by large ſtones. The whole of this formed a place of worſhip among the antient Britons, and probably was ſurrounded with a grove. But what I have to ſay on the ſubject of Druidiſm, is reſerved till I reach Angleſea, its principal ſeat."

One can still find, on the summit of the isolated hill of Y Foel (52.9544N, 3.44849W), an oval enclosure known as the "Y Gaerwen Enclosure" of very meagre earhworks, c.92m by 70m. It is defined by scarps thought to represent the robbed remains of a wall.

The introduction of a farming economy is one of the major developments of human history, yet the process by which he changed from an essentially passive user of his environment to an active manipulator of plants and animals is one which is poorly understood. The appearance of new crops and domestic animals must indicate some colonisation from Europe where farming had been established for at least two millennia before its adoption in Britain in the 4th millennium BC. One consequence of agriculture was that pathogens which had once been exclusive to animals transferred to humans, with these animal diseases leaping the species gap and mutating into contagious human diseases. This transmutation of disease is still apparent, as it is believed that humans nowadays share more than sixty micro-organic diseases with dogs, and only slightly fewer with cattle (TB, smallpox, measles), sheep, goats, pigs (flu), and poultry (flu). Hunter/gatherers died from causes of nature but were practically unfamiliar with diseases (which survived poorly in small populations), while farming communities offered a new chance for pathogens to spread but provided a more stable food source. Settlement also increased malaria, as farmland created the warm water-holes and furrows which make perfect breeding environments for mosquitoes. Despite the increasing population pressure and rise in disease, humans did not prove totally defenseless against the onslaught of disease, as survivors of epidemics acquired some antibody protection which allowed for the immune system to become more sophisticated over time. Of course, if the farmers still carried the diseases in a weakened form, contact with the hunter-gatherers could prove fatal for the latter.