Suspension Bridge

History

The Queen's Park Suspension Bridge connects The Groves with the affluent Queen's Park area of Chester. Queen's Park was planned on a greenfield site immediately south of the River Dee and next to the Earls Eye in 1851 by Enoch Gerrard and others. It was developed in the 1850s and 1860s as a middle class residential suburb. The Duke of Westminster originally intended to have the area laid out as a model industrial suburb but Victoria Pathway remains the only part of this vision that was realised. The residential development of Queen’s Park was slow and only four villas and two semi-detached pairs had been built by 1873. By 1910 the total had still reached only 17, although a further 10 houses had been built on St. George's Crescent to the south. The experience there, and at Curzon Park, suggests that the demand for exclusive property in Chester was smaller than the amount of sites available. On the southern edge of Queen's Park some smaller semi-detached houses had appeared in the mid 19th century around Victoria Pathway. There has since been extensive inter-war and post-war infill and eastward extension to the suburb.

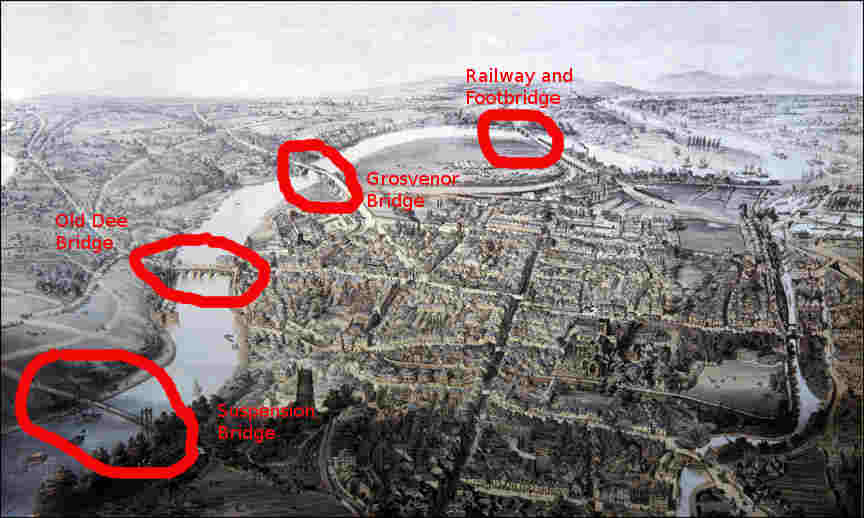

The suspension bridge is the only footbridge to cross the River Dee in Chester apart from the footbridge attached to the railway bridge. It was originally built in 1852 at the instigation of Enoch Gerrard, Esq., the "projector and proprietor" of Queen's Park, the developing suburb across the river. According to Thomas Hughes, author of "The Stranger's Handbook to Chester":

- "It was 'a pretty object in the landscape. Though of such spider-like construction, its capabilities and strength have been fully tested".

Chester Corporation took on the responsibility for this bridge in the early 1920s and decided to demolish it almost at once - presumably because there was some serious structural problem and Chester was already noted for one bridge collapse disaster when the Dee Railway Bridge gave way under a passing train in 1847. The demolition of the suspension bridge took place in August 1922. It was replaced by a new bridge "designed" by Charles Greenwood, City Engineer and Surveyor ("designed" because it is almost a copy of another bridge). The opening ceremony, conducted by the Mayor of Chester, Councillor S.R. Wall, took place on 18 April 1923. It was superbly restored in 1998 and again in 2012 (although it soon needed repairs to the footway and the "shields" are still wrong).

The 1923 bridge bears a striking resemblance to the 1922 Porthill Bridge in Shrewsbury - so much so that many people, even Chester residents, might have problems telling which was which in photographs. However, Chester's bridge has real shields rather than the tiny ones in Shrewsbury and a huge sign saying which one it is.

Like many suspension bridges the Chester bridge exhibits some "spring" when walked across. It is a common belief that any troops which cross it are required to "break step" to prevent excessive vibration. The bridge gets generally positive reviews on "Trip Advisor" (with comments like "can be used to cross the river").

Confused Coats of Arms

The arms of The Earls of Chester are described in detail in Cheshire Antiquites (Strutt, 1838) as:

- Hugh of Avranches: 1st Earl of Chester, created (1070-1101) - "Azure, a wolf's head argent" (silver wolf's head on blue)

- Richard of Avranches: 2nd Earl of Chester (1101-1120) - "Crusilly, a wolfs head" (wolf's head with crosses)

- Ranulf de Meschines: 1st Earl of Chester (1120-1129) - "Or, a lion rampant gules" (red lion on gold)

- Ranulph De Gernon: 2nd Earl of Chester (1129-1153) - "Gules, a lion rampant argent" (silver lion on red)

- Hugh de Kevelioc: 3rd Earl of Chester (1153-1181) - "Azure, six garbs or" (six gold sheaves on blue)

- Ranulf de Blondeville: 4th Earl of Chester (1181-1232) - "Azure, three garbs or" (three gold sheaves on blue)

- John Canmore: known as "John the Scot" Earl of Chester (1232-1237) - "Or, three piles gules" (three red wedges on gold)

It appears that the arms of Ranulf de Meschines and Ranulf de Gernon have been switched around on the suspension bridge. Some of the early coats of arms are very distinctive and appear to have "grabbed" very simple combinations of heraldic symbols - such as a rampant red lion on gold. These, as compared with later more complex coats, can be compared with "vanity number plates" in terms of their availability. Curiously, the same "swap" is found in the chronicle of Dieulacres Abbey (founded by Ranulph III) which, in its present form, appears to date from the early fifteenth entury. On f. 137 this lists the earls of Chester, ‘founders of Dieulacres’, with their traditional surnames; but although it has the dates of Ranulph I (‘ Meschenes’) and Ranulph II (‘Gemons’) approximately correct, it gets these names the wrong way round.

The shields had become rather weather-beaten over the years, and were impressively restored by David Kynaston in 2012/13. Cast out of lead, broken and missing parts were repaired. The shield were fully repainted and finished in 23 1/2 carat gold leaf. The "silver" wolves heads were finished in palladium leaf. Palladium is a rare metal and the major sources include the impact sites of meteorites. Thus, the "silver" on the suspension bridge may well be of extra-terrestrial origin.

Gallery: the Earls of Chester, their arms, and the arms on the bridge

According to some sources between 1067 and 1070 Gherbod the Fleming was created first Earl of Chester, holding a large portion of that county along with the city of Chester forming the county palatine of Chester. Gerbod was mentioned as being a part of the reduction of Cheshire in 1070 by the Conqueror. Orderic Vitalis (modern historians view him as a reliable source) reports that Gerbod was harassed by both English and Welsh in his new position and he may have been glad to return to Flanders later that same year. This may also have been due to concerns having to do with the death of the Count of Flanders, Baldwin VI, and the subsequent civil war. According to Orderic he fought in the Battle of Cassel in February 1071 in Flanders where he fell into the hands of his enemies and was held captive. William I, seeing the earldom vacant, used his imprisonment as a reason for giving the earldom of Chester to Hugh 'Lupus' d'Avranches. The Hyde Chronicle reported Gerbod died a prisoner. However, an English and a Norman source both state that Gerbod was not imprisoned following Cassel. Instead he fled to Rome to seek forgiveness for the sin of killing Arnulf III, Count of Flanders, his liege lord during the battle. Gherbod does not appear on the suspension bridge and the shields are made up to eight with the arms of Chester. In any event, there is no description of Gherbod's arms.

The Earldom reverted to the Crown in 1237 on the death of John the Scot (aged 30). However, the reversion was not as simple as most histories describe. William de Forz (Latinised as de Fortibus, sometimes spelt Deforce), 4th Earl of Albemarle, (died 1260) claimed that, as a Palatinate, it could not be divided, and his wife should get it as the oldest coheir. William got the title, but the court decided that the lands should be divided. However, he and his wife (Christina (d. 1246), daughter and co-heiress of Alan, Lord of Galloway) quitclaimed the earldom to Henry III in 1241 in exchange for modest lands elsewhere. So the last Earl of Chester may be described as William de Forz, and he held the title for four years, only a little less than John the Scot. William de Forz played a conspicuous part in the reign of Henry III of England, notably in the "Mad Parliament" of 1258.

The Earldom was formally annexed to the Crown in 1246 when the rest of the honour of Chester (the land) was bought from the rest of Ranulph's sisters by Henry III. King Henry III passed the Lordship of Chester, but not the title of Earl, to his son the Lord Edward in 1254, and as King Edward I he conferred the title and the lands of the Earldom first on son, Edward, the first English Prince of Wales. By that time the Earldom of Chester consisted of two counties: Cheshire and Flintshire.

The Earls at the Town Hall

Eight Earls are depicted in stained glass on the staircase at the Town Hall (Gherbod the Fleming is also included, but he doesn't feature on the bridge, possibly because there appears to be no record of his coat of arms). The coats of arms in the Town Hall appear to be the right way round.

Facing the stained glass in the Town Hall is an even bigger historical howler, a relief entitled: "Edward Price of Wales Receiving Homage: First Royal Earl Of Chester AD 1254". King Henry III passed the Lordship of Chester, but not the title of Earl, to his son the Lord Edward (later Edward I) in 1254, and as King Edward I he in turn conferred the title and the lands of the Earldom on son, Edward (later Edward II), who was also made the first English Prince of Wales in 1301, when King Edward I of England, completed the conquest of Wales. So the figure above the doors of the Mayor's parlour is not Edward I ("Hammer of the Scots") but his somewhat disappointing son Edward II (of hot poker fame), Prince of Wales, who was only born in 1284. In 1254, his parents had probably not even met.

Arms according to Joseph Strutt

Joseph Strutt (27 October 1749 – 16 October 1802) was an English engraver, artist, antiquary, and writer. He is today most significant as the earliest and "most important single figure in the investigation of the costume of the past", making him "an influential but totally neglected figure in the history of art in Britain", according to Sir Roy Strong

Strutt's allocation of the arms is confirmed by some "stained glass" now housed at Stoneleigh Abbey: a series of late-sixteenth-century panels that depict the seven independent earls of Chester and two earls of Mercia. Each earl, identified by an inscription, is shown standing beneath a decorative arch, brandishing a drawn sword and wearing armour, a coronet, and a surcoat emblazoned with his arms. Their original position at Brereton Hall is not recorded, but it seems likely that this grand parade of local potentates was commissioned (around 1577), by Sir William Brereton for the Withdrawing Room, which with its frieze and overmantel was the finest room in the Hall. The earls were certainly in the bay window of the Withdrawing Room in 1808, when an engraving of them was published by William Fowler, a celebrated artist of the period whose images did much to publicise a variety of historical artworks, including stained glass. Fowlers engraving shows Ranulf de Meschines as having a red lion on a gold field and Ranulf de Gernons having a white lion on a red field.

The arms also appear on armorial boards at Chester Cathedral where Strutt's pattern is followed having the cottect red lion on gold for Ranulf I and a silver lion on red for Ranulf II.

Arms on the lodge in Grosvenor Park

These were repainted in 2013 and have almost the correct colours, although the style of armour they are wearing is from hundreds of years later.

Arms on the Bridge Before Restoration

Even before restoration the arms on the suspension bridge were "mixed-up". While the "silver on red" arms are badly tarnished, it still seems fairly clear that this was not the "gold on red" it was restored to, and it is in the wrong place anyway.

After Restoration

The restorer was somewhat dumb-founded when the error was pointed out, but it was hardly his fault given that he had been given detailed instructions.

Padlocks

Young people today have a habit of placing padlocks on bridges. These typically have a romantic message written on them - and are often known as "Love-Locks". Notable examples of such bridges include those in Paris, Serbia (where it started) and elsewhere. In 2013 there were a bondage-lovers paradise of such locks on the Suspension Bridge, and then, they started to disappear. It turned out that a local resident had taken it upon himself to remove them. However, exposure in a "U-Tube" video seemed to end that.

Flash-forward to 2014: as reported in the Chester Chronicle, Cheshire West and Chester Council have stated that the locks could make the bridge dangerous, as they could make the bridge "sway" in high winds. The Chester bridge had just 330 locks attached to its railings - weighing a total of about 24Kg or 3.77 stone. Council Engineers apparently said to the Chronicle that the extra weight of the padlocks has brought the bridge "close to its theoretical capacity to resist the effects of wind loading".

Undoubtedly fears were sparked after part of the Pont de Arts in Paris collapsed under the weight of 700,000 of the locks in 2014. To be fair enough, this is not about an extra 25kg of weight in the case of Chester, but more probably about the wind-resistance that the locks might create or shifts in the resonant frequency of the bridge (see: Tacoma Narrows), and the potential litigation that might happen if anyone does have an accident within ten miles of the bridge and sues the Council for negligence.

Sources and links

Related Pages

- More on sus bridge;

- Historiography: some more history howlers from Chester;

Online

- A Grand Day Out in Chester: celebrating 100 years of the new Queens Park Suspension Bridge;

- Virtual Stroll shows the original bridge;

- The original chain bridge on "bridgemeister".

- The current bridge on "bridgemeister"

- Love-locks on the BBC;

- FOI request on the locks;