Ælfgar

In 1013, just over a half-century before the Norman Conquest, England was successfully invaded and shortly thereafter conquered for the first time since the coming of the Anglo-Saxons some 500 years before.

A quarter-century later an "English King" would return for a final-quarter century of Anglo-Saxon rule, but the reign of this king, Edward the Confessor, would provide the backdrop for a conflict between Wessex and Mercia that was barely short of civil war. The roots of this conflict stretch back to the descent of the once dominant Midlands kingdom of Mercia into chaos during the 9th Century and the rise of the southern power of Wessex in the 10th. Both of these Anglo-Saxon kingdoms would be subject to invasion and almost complete conquest by the Vikings. The early 11th century would see the Scandinavians finally rule England after a conquest which involved St Olave of the same-named church in Lower Bridge Street.

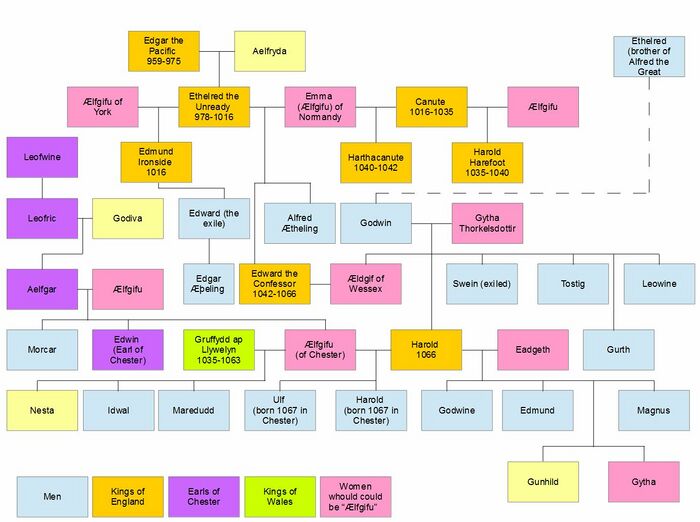

The history is normally viewed from the perspective of Wessex, however it is also possible to take a perspective from the Mercian position, especially that of the House of Leofric. Leofric is almost unknown to the general reader although many have heard of his wife, Godiva, famous for riding through Coventry in a state of undress. Leofric's son Ælfgar and the next generation in turn played a major part in the historic events either side of 1066. Events in Wales and across the Welsh/Mercian border are also of some interest especially as regards Chester. in the interest of historiography the usual the general disclaimer applies that the objective is not to make Chester any more important than it actually was, but to illustrate history with reference to the familiar.

Many history books and other historical writing (including historical fiction) need to be treated with some caution as the writer often has their own viewpoint and agenda. Charles Kingsley provides a relevant local example. He is often portrayed as a writer who lived and worked in Chester although he actually spent a very short time here. Although he was for some time a Professor of History at Cambridge, his view of history is now considered to have been much biased by his views on race and religion. His historical novels distort facts to support his views on "Anglo-Saxon" superiority.

The short "Victorian" version is that the Romans left and the British (Welsh) were left behind to be invaded by the Angles and Saxons (who were German, like Prince Albert), but soon became the English. Other surrounding "races" included the primitive Irish, Picts (Scots) and the Vikings. The Victorians portrayed these as brave and useful cannon-fodder (provided they were English led). Eventually, the Normans invaded but eventually learned to see the sense of not being French and to speak English. The most successful Viking, Cnut, is portrayed as a ruler who foolishly attempted to hold back the tide.

The "Wessex" Perspective

For convenience the history of "how London started to become the capital of the world" can be broken into several parts:

- The fall of Mercia from the rule and eventual death of Offa (796);

- The rise of Wessex from the ascention of Ecgbert and the subsequent Danish invasions and reconquest;

- A further wave of Viking raids and invasions under Æþelræd (the "Unready");

- A period of Scandinavian rule;

- The reign of Edward the Confessor;

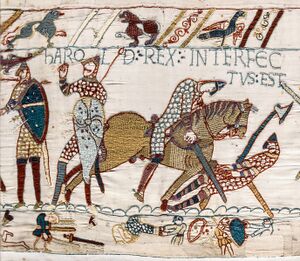

- The brief reign of Harold and the coming of the Normans;

Offa to Edgar the Pacific

Mercia reached its peak under Offa (died 29 July 796 AD), who may or may not have built the border structure known as Offa's Dyke, and which may or may not have stretched from the Dee to the Severn. Offa's reign was once seen as part of a process leading to a unified England, but this is no longer the majority view: in the words of a recent historian:

- "Offa was driven by a lust for power, not a vision of English unity; and what he left was a reputation, not a legacy."

Debate over the dating and purpose of Offa's Dyke continues to this day. "Ofer" means "border" or "edge" in Old English (and even "shore"), giving rise to the possibility of alternative derivations for some border features associated with the man named Offa. Some late Roman writers such as the Eutropus mention a wall being built in late Roman times across Britain "from sea to sea". This is often repeated by later writers in the British isles and for many years it was thought that this was certainly simply a confused mention of Hadrians Wall. However some have now suggested that this is in fact a reference to what was later to become known as "Offa's Dyke". There are arguments on both sides. Radio-carbon dating is also inconclusive and can be interpreted to suggest that the Dyke predates Offa, i.e. that it was a much longer established border of some kind, perhaps dating from soon after the Roman departure. The Dyke roughly (but not exactly) follows the border between the part of Britain that had been colonised mostly by the Angles and that part which became known as Wales, and the present structure has a ditch-and-bank arrangement which favours defence of the eastern side against the west. Thus the Dyke can be thought of as the western border of the Anglian kingdom of Mercia: the eastern border being towards or on the coast of the North Sea.

Offa's son, Ecgfrith, succeeded him, but reigned for less than five months. Offa had ruthlessly eliminated dynastic rivals leaving only his son. This seems to have backfired, from the dynastic point of view, as no surviving close male relatives of Offa or Ecgfrith are recorded, and Coenwulf, Ecgfrith's successor, was only distantly related to Offa's line. Coenwulf's early reign was marked by a breakdown in Mercian control in southern England. South of the Thames, Britain had been mostly colonised by the Saxons. During Offa's time Mercia mostly dominated the Saxons south of the Thames, but after his death this control rapidly weakened. To the north of Mercia was the border with the kingdom of Northumbria - effectively for much of the time the border was marked by the River Humber.

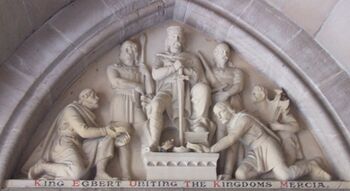

Coenwulf the Mercian died in 821 at Basingwerk near Holywell, Flintshire, probably while making preparations for a campaign against the Welsh that took place under his brother and successor, Ceolwulf, the following year. Coenwulf was the last of a series of Mercian kings, beginning with Penda in the early 7th century, to exercise dominance over most or all of southern England. Ecgbert (Ecgberht) of Wessex ruled from 802-839, and is thought to be descended from the founder of Wessex, Cerdic (514-534), despite being the son of a Kentish noble. He was sent into exile by Offa in 789, and resided at the court of Charlemagne for three years. Ecgbert took back Wessex in 802 when his rival Beorhtric was poisoned by his own wife, Eadburh (possibly by accident). In the years after Coenwulf's death, Mercia's position weakened, and the Battle of Ellendun in 825 firmly established Egbert of Wessex as the dominant king south of the Humber. He was 55 at the time and would remain ruler of Wessex until the age of 69. Ecgbert is commemorated at Chester Town Hall in one of a series of bas-reliefs showing what are supposed to be key moments in Chester's history. The previous event in the sequence is the establishment of Roman Chester after 70 CE, the next the formation of the Norman Earldom around 1070. Whoever chose the sculptures clearly thought that in a thousand years the only relevant thing that happened in Chester was a brief invasion by a man from Kent.

The lineage of Ecgbert would continue to be associated with Chester. Ecgbert's son Æthelwulf supposedly recieved the submission of other kings "from Berwick to Kent" at Chester, as mentioned in Ormerod. However, this is only mentioned in a late source and may be a historical fiction. Æthelwulf then went on pilgrimage to Rome and returned to find his "caretaker" brother would not give up the kingdom. Egbert's grandson, Alfred the Great (848/849 – 26 October 899) fought back from a Danish invasion (which saw him reduced to ruling a few squere miles of swamp) to a stalemate where the Danes ruled the eastern half of the country. The dividing line between the English lands and those ruled by the Danes was Roman Watling Street which runs more or less directly from London to Chester - although it must not be discounted that near Chester "Watling Street" may preserve a separate derivation from the Old English wealhas ("foreigner" = "Welsh") given the use as trade routes to and from Wales.

Alfred apparently fought Vikings at Chester. Alfred's son Edward (c. 874 – 17 July 924) regained much of the lost territory with the aid of his warlike sister, Æthelflæd, who rebuilt Chester, then Edward died at Farndon after dealing with a revolt in Chester. Next came Æþelstān (c. 894 – 27 October 939) who may have fought the Battle of Brunanburh near Chester and first called himself "King of the English". Upon his death England fell apart. Chester was an important base in 942 when there was collusion between the Welsh and the Scandinavian kingdom of York during King Edmund's campaign against the latter.

England was once again united under Edward the Elder's grandson Edgar the Pacific (c. 943 – 8 July 975) who famously cruised on the River Dee, possibly from Edgar's Field to proclaim his "wide rule" over the British Isles, and upon his death England once more collapsed into chaos.

Æþelræd (the "Unready")

Edgar's 973 voyage on the River Dee represented another high tide in the affairs of kings: he would be dead two years later. His eldest son soon fell victim to political murder, leaving the throne to Æþelræd "the unready". Two years later, the Vikings started fresh raids.

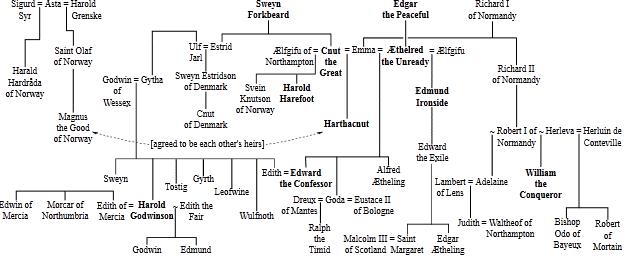

The Danish House of Knýtlinga ruled the Kingdom of England from 1013 to 1014 and from 1016 to 1042. In 1013 Sweyn Forkbeard, already the king of Denmark and of Norway, overthrew King Æþelræd the Unready of the House of Wessex. Sweyn had first invaded England in 1003, possibly to avenge the death of his sister Gunhilde and many other Danes in the St. Brice's Day massacre, which had been ordered by Æþelræd in 1002. His motivations almost certainly included the prospect of plunder. Sweyn died in 1014 after ruling England for five weeks, and Æthelred was restored. However, in 1015 Sweyn's son, Cnut the Great, invaded England.

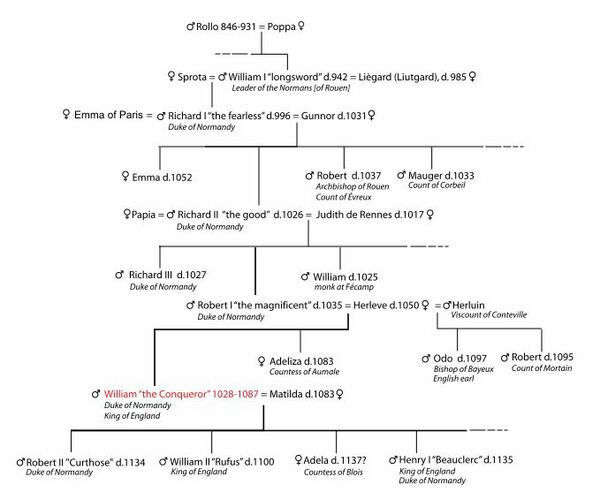

After Æþelræd died in April 1016, his son Edmund Ironside briefly became king, but was forced to surrender half of England to Cnut. After Edmund died in November that same year, Cnut became king of all England. Scotland submitted to him in 1017, and Norway in 1028. Cnut died on 12 November 1035. In Denmark he was succeeded by Harthacnut, reigning as Cnut III, although with a war in Scandinavia against Magnus I of Norway, Harthacnut was "forsaken [by the English] because he was too long in Denmark". His mother Queen Emma, previously resident at Winchester with some of her son's housecarls, was made to flee to Bruges in Flanders, under pressure from supporters of Cnut's other son, after Svein, by Ælfgifu of Northampton: Harold Harefoot — regent in England 1035–37 (who went on to claim the English throne in 1037, reigning until his death in 1040). Eventual peace in Scandinavia left Harthacnut free to claim the throne himself in 1040. He brought the crowns of Denmark and England together again until his death in 1042. Denmark fell into a period of disorder with a power struggle between the pretender to the throne Sweyn Estridsson, son of Ulf, and the Norwegian king, until the death of Magnus the Good in 1047. The inheritance of England was briefly to return to its Anglo-Saxon lineage: the house of Wessex reigned again as Edward the Confessor was brought out of exile in Normandy and made a treaty with Harthacnut, his half-brother. As in his treaty with Magnus, it was decreed that the throne would go to Edward if Harthacnut died with no legitimate male heir. In 1042, Harthacnut died, and Edward was king. His reign secured Norman influence at court thereafter, and the ambitions of its dukes finally found fruition in 1066 with William the Conqueror's invasion of England and crowning, fifty years after Cnut was crowned in 1017.

If the sons of Cnut (Harold Harefoot and Harthacnut) had not died within a decade of his death, and if his only known daughter Gunhilda (Cunigund), who was to marry Conrad II's son Henry III eight months after Cnut's death, had not died in Italy before she became empress consort, Cnut's reign might well have been the foundation for a complete political union between England and Scandinavia: a post-Viking North Sea Empire with blood ties to the Holy Roman Empire. It was not to be, England returned to Anglo-Saxon rule briefly but with considerable influence from the Normans to the south. Eventually it would become clear that a Norman invasion lay ahead.

The "Mercian" Perspective

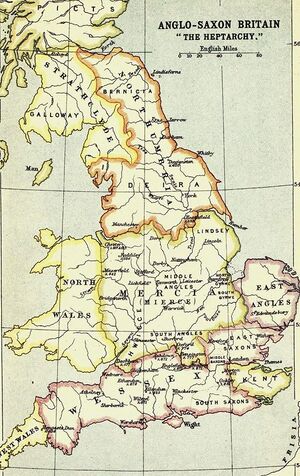

In many ways Mercia was the dominant English kingdom for three centuries, between about 600 and about 900. In much later medieval times, historians would begin to refer to the early Anglo-Saxon kingdoms as the "Heptarchy", listing its members as East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Mercia, Northumbria, Sussex, and Wessex. Although heptarchy suggests the existence of seven kingdoms, the term is just used as a label of convenience and does not imply the existence of a clear-cut or stable group of seven kingdoms at all times. The number of kingdoms and sub-kingdoms fluctuated rapidly as kings contended for supremacy. In the late 6th century, the king of Kent was a prominent lord in the south. In the 7th century, the rulers of Northumbria and Wessex were powerful. In the 8th century, Mercia achieved hegemony over the other surviving kingdoms, particularly during the reign of Offa. Mercia was a perculiar state in that it does not appear for much of its existence to have had a capital as such, but made use of a "portable court" with the ruler moving from place to place and perhaps over-wintering at a royal estate.

Alongside the seven kingdoms, a number of other political divisions also existed, such as the kingdoms (or sub-kingdoms) of: Bernicia and Deira within Northumbria; Lindsey in present-day Lincolnshire; the Hwicce in the southwest Midlands; the Magonsæte or Magonset, a sub-kingdom of Mercia in what is now Herefordshire; the Wihtwara, a Jutish kingdom on the Isle of Wight, originally as important as the Cantwara of Kent; the Middle Angles, a group of tribes based around modern Leicestershire, later conquered by the Mercians; and the Hæstingas (around the town of Hastings in Sussex). The decline of the Heptarchy and the eventual emergence of the kingdom of England was a drawn-out process, taking place over the course of the 9th to 10th centuries. Over the course of the 9th century, the Danish enclave at York expanded into the Danelaw, with about half of England under Danish rule. The English unification under Alfred the Great was a reaction to the threat by the common enemy. In 886, Alfred retook London, and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says that:

- "all of the English people (all Angelcyn) not subject to the Danes submitted themselves to King Alfred".

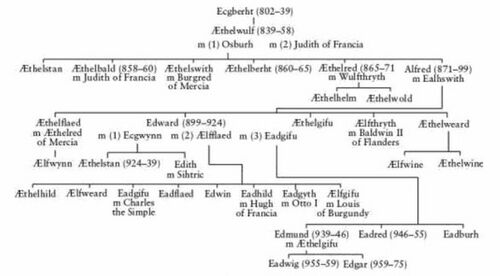

After Alfred and up to the time of the Norman Conquest it is generally true that the "English" were, with some brief exceptions the subjects of a single king, although the borders with the scandinavian-settled north varied. Including Alfred himself, several kings ruled for more than five years. These rulers were: Alfred (871-89), Edward the Elder (899-924), Æthelstan (924-939), Edgar the Pacific (959-975), Æthelred the Unready (978-1016), Cnut (1016-1035) and Edward the Confessor (1042-1066).

The Normans were successful in their invasion and from that point on the telling of English history was dominated by relations with the continent to the south. The Mercians appear to leave the stage with the rise of Wessex (mostly told as being the work of Alfred) and Wessex is in turn "triumphant" over the Vikings before being defeated by the Normans (mostly told from the perspective of Harold). The Viking conquest of the early 11th Century is largely forgotten, with the Vikings often being portrayed as unsophiticated pirates. Even the word viking is a historical revival; it was not used in Middle English, but it was revived from Old Norse vikingr "freebooter, sea-rover, pirate, viking," which usually is explained as meaning properly "one who came from the fjords," from vik "creek, inlet, small bay" (cf. Old English wic, Middle High German wich "bay," and second element in Reykjavik). But Old English "wicing" and Old Frisian "wizing" are almost 300 years older, and probably derive from "wic" "village, camp" (temporary camps were a feature of the Viking raids), related to Latin "vicus" "village, habitation". The Viking attack on Lindisfarne in 793 was the first of many raids on monasteries of Northumbria and the east coast. In 865, instead of raiding, the Danes landed a large army in East Anglia, and had soon conquered a territory known as the Danelaw, including Northumbria, by 867. After 867, there was an influx of Scandinavian immigrants. Their religion was "pagan" polytheism and had a rich mythology. Within the Kingdom of York, once the raids and war were over, there is no evidence that the presence of Scandinavian settlers interrupted Catholic practice. It appears that they gradually adopted Catholicism and blended their Scandinavian culture with their new religion.

Victorian Historians

There is perhaps a tendency among Victorian historians and those who lived through the two world wars, as well as those educated by them, to see early English history as a a series of threats to the "Anglo-Saxon people" by continental Europeans, be they "Vikings" (who might actually be Danes) or "the French" (who might be Normans).

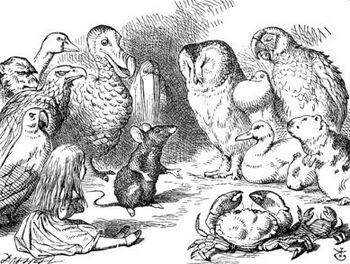

The house of Leofric is hardly mentioned, except perhaps for a brief mention of Godiva, or as in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland when the mouse attempts to dry itself and other sodden characters by reciting a "dry" example of English history:

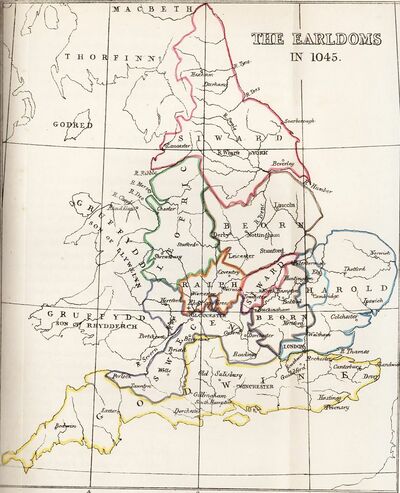

- "At last the Mouse, who seemed to be a person of authority among them, called out, 'Sit down, all of you, and listen to me! I'll soon make you dry enough!' They all sat down at once, in a large ring, with the Mouse in the middle. Alice kept her eyes anxiously fixed on it, for she felt sure she would catch a bad cold if she did not get dry very soon. 'Ahem!' said the Mouse with an important air, 'are you all ready? This is the driest thing I know. Silence all round, if you please! "William the Conqueror, whose cause was favoured by the pope, was soon submitted to by the English, who wanted leaders, and had been of late much accustomed to usurpation and conquest. Edwin and Morcar, the earls of Mercia and Northumbria--"' "

The mouse attempts to continue his tale but is shouted down and never gets to recite the history of the last of the House of Leofric. This inclusion in Carroll's book is made interesting as he is distantly related to both Edwin and Morcar and will draw on his own Cheshire background to provide the better-known "Cheshire Cat". The story which the mouse tells is not really that "dry" to anyone interested in the fascinating complexity of the succession of English kings and other political shifts: especially from around the time of Edgar's boat trip on the River Dee (possibly upstream from Edgar's Field ot downstream from Farndon) to the Hermitage which is associsated (possibly only in legend) with Harold II.

Back to Edgar

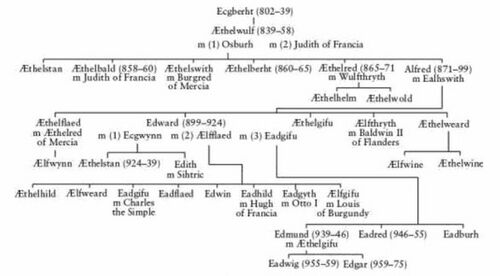

The succession of English rulers from the time of Ecgbert (as portrayed on the Town Hall) to William the Conqueror (as also portrayed on the Town Hall) was seldom simple and straightforward. Few eldest sons simply succeeded their father as king. There were at times children too young to rule and sometimes very young kings. Sometimes a crown would pass between brothers. There were successions following murder or other untimely deaths, usurpations and invasions. Two kings were notable for their self-imposed chastity and several potential heirs died without children or before even becoming king. At times, the country was divided with two kings ruling at the same time, at others there were arrangements that the longest surviving of rivals would become king. Of the various rulers, some would hold the throne for many years, while some would come and go in quick succession.

The story of the queens (or consorts) is equally complicated, with several being married to more than one ruler or because a male ruler had children by more than one queen. There were some rules for succession, but either politics intervened or there was a need for an adult ruler in times of war. On the other hand, Victorian historians seem to have thought that the "Witan" (a body of nobles and churchmen) had a far greater role in deciding kingship than they actually did, possibly because they liked to think that the "Witan" was some kind of early democratic parliament, which it wasn't. There is a chronology and family tree charts in the reference section below.

Of the late Anglo-Saxon kings the one most closely associated with Chester is Edgar the Pacific. King Edgar (c. 943 – 8 July 975) was King of England from 959 until his death at the age of 32. He was the younger son of Edmund I and Ælfgifu of Shaftesbury, and came to the throne as a teenager, following the death of his older brother Eadwig. He is famous for his "boat-trip" on the River Dee, where he "recieved the submission" of other rulers of the British Isles. The identity of these other rulers is discussed in further detail on the page relating to Edgar's Field. Edgar is commemorated in Chester in several ways: the name of the field and the park being the most prominent, although there is also a notable work of sculpture in the park. His boat trip is depicted in stained glass at St Johns and in tiles at the Bull and Stirrup in Northgate Street. He appears, in his boat, as an anachronism on many old maps of Chester. An inn known as "Ye Old Edgar" once stood at the bottom of Lower Bridge Street, there is an "Edgar House" hotel and an Edgar Place.

In Victorian times the story of King Edgar served English political and cultural ends, being used to demonstrate the "natural superiority" of the English over the others in the Union, particularly the Scots and Welsh. It did not start with the Victorians: the earliest independent reference to what is apparently the same boat trip is that of Ælfric of Eynsham, in his Life of St Swithin:

- "and ealle ða cyningas þe on þissum iglandewæron, Cumera and Scotta comon to Eadgare, hwilum anes dæges eahta cyningas and hiealle gebugon to Eadgares wissunge" - (and all the kings who were in this island, British and Scots, came to Edgar, at one time eight kings on one day, and they all submitted to Edgar's direction)

Gallery on "Time's Hand"

Minerva Shrine and chisel marks

The above photo's were taken in September 2017. Works like this in the public domain reference history and associated legends but there is frequently a gap between the effort that has gone into producing them and the public perception of what they represent.

Edmund I's Murder

Edgar's father Edmund had been just three years old when his own father, Edward the Elder died on July 24, 924 at Farndon. Succeeding Edward was Edmund’s 30-year-old half brother Æthelstan, who quickly saw the death of one rival claimant and later may have killed off another. Thanks to Æthelstan's warlike activities Edmund I was the first Anglo-Saxon monarch whose dominion extended over the whole of England at the time of his accession in 939. It was not long before Edmund faced opposition. In 940, Olaf Guthfrithsson, King of Dublin, who was defeated by Æthelstan in the Battle of Brunanburh, came down from Northumbria to reclaim his lost lands in York. Olaf and Edmund met in 939 at Leicester where they came to an agreement regarding the division of England between them. This agreement proved short-lived, however, and within a few years Vikings had occupied the Five Boroughs of Derby, Leicester, Lincoln, Nottingham and Stamford. When Olaf died in 942, Edmund reconquered the area of the Five Boroughs. In 944 Edmund retook Yorkshire and Northumbria, and subdued Strathclyde in 945. Also in 945 he became embroiled in the politics of France when he helped restore Louis IV. Clearly Edmund would have made enemies during this time.

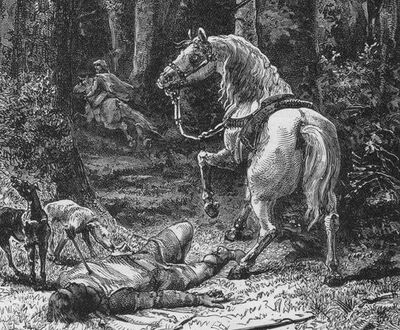

On May 26, 946, Edmund I, the twenty four year old King of the English, was stabbed to death at a royal hunting lodge in Pucklechurch, north of Bath, England while celebrating the feast of St. Augustine of Canterbury. The murderer was at once hacked to pieces by the king's supporters. The traditional story is that he was stabbed by a thief who had been banished some years before. Recent research indicates that Edmund may have been the victim of political assassination and suggests that the characterization of Edmund’s killer as a thief was fabricated by later chroniclers. In fact, the chronicle versions are contradictory and would have us believe that a banished thief acting alone turns up at a royal celebration and manages to get himself a seat on the "top table" without anyone noticing. Edmund’s killer was not named in any chronicles for more than 100 years after his death and the name that eventually appeared was probably chosen on purpose because its meaning was understood all too well. In Old English "leof(a)" meant "beloved" and so the use of the name Leofa for an assassin seems quite ironic. William of Malmesbury says in his chronicle that "…rumours about his death…spread all over England." Some of these rumors may have blamed the person who had the most to gain from Edmund’s death – his younger brother Eadred. Edgar the Pacific's uncle Eadred became the next king of England.

Upon the murder of King Edmund in 946, Edgar's uncle, Eadred, ruled until 955. Eadred succeeded to the throne over his two young nephews who were deemed too young to rule. He would be the third and last of the sons of Edward the Elder to rule England. The chonicles about his reign are notoriously confused. Eadred inherited a volatile political climate from his brother Edmund. It appears that he soon lost the Kingdom of York to the Vikings (under Olaf Sihtricson and Eric Bloodaxe) and only managed to regain it firmly in 952. During his reign Eric Bloodaxe was killed in an ambush, along with five kings from the Hebrides and the two earls of Orkney, on the bleak moors of Stainmore in Teesdale by Maccus, an agent of Oswulf Ealdulfing, the High Reeve or Earl of Bamburgh, who ruled Northumbria north of the Tees. Oswulf was a supporter of Edred, who may have encouraged the murder. Towards the end of his life, Eadred suffered from a digestive malady which would prove fatal and he died at the age of about 31. An ornate mortuary chest at Winchester Cathedral is said to contain Eadred's bones.

Eadred was succeeded by his nephew, the 15 year old Eadwig, Edmund's eldest son. Eadwig's short reign was tarnished by disputes with nobles and men of the church, including Archbishops Dunstan and Oda. According to one legend (written about the year 1000), the feud with Dunstan began on the day of Eadwig's coronation, when he failed to attend a meeting of nobles. When Dunstan eventually found the young monarch, he was "cavorting" with a noblewoman named Ælfgifu and her mother (Æthelgifu), and refused to return with the bishop. Infuriated by this, Dunstan dragged Eadwig back and forced him to renounce the girl as a "strumpet". Just what "cavorting" implies is left to the reader: in Eadmer’s Life of St Oda, the archbishop subsequently sent soldiers to seize the woman with whom the king had most frequently "cavorted in rude embraces". Later realising that he had provoked the king, Dunstan fled to the apparent sanctuary of his cloister, but Eadwig, incited by Ælfgifu, whom he had married, followed him and plundered the monastery. Dunstan was forced into exile. These stories, written down some 40-odd years later, seem to be rooted in later smear campaigns which were meant to bring disrepute on Eadwig and his marital relations.

Eadwig is known for his remarkable generosity in giving away land. In 956 alone, his sixty odd gifts of land make up around 5% of all genuine Anglo-Saxon charters. No known ruler in Europe matched that yearly total before the twelfth century, and his cessions are plausibly attributed to political insecurity. Eadwig was dead at the age of 19. The circumstances of his death are not recorded and although there is no mention of foul play on the part of the supporters of Edgar, it cannot be ruled out.

Edgar's Upbringing

Edgar was about 3 when his father was assassinated on 26th May 946 and was adopted by Æthelstan Half-King an important and influential Ealdorman of East Anglia. One reason for this may well have been to protect him from possible risks of himself being assassinated as his father had been, especially given the ambition of Ælfgifu and her family, who may well have wanted an heir of Eadwig to be the next king. The union between Ælfgifu and Eadred was or was to become one of the most controversial royal marriages in 10th-century England. Eadwig's brother Edgar was the heir presumptive, but a legitimate son born out of this marriage would have seriously diminished Edgar's chances of succeeding to the kingship. The annulment of the marriage of Eadwig and Ælfgifu is unusual in that it was against their will, clearly politically motivated by the supporters of Dunstan. The Church at the time regarded any union within seven degrees of consanguinity as incestuous. At the time, "degree" was reached by counting up to the common ancestor: a second cousin would have been related within the third degree.

The rise of Æthelstan's family began in the reign of King Edward the Elder, when his father Æthelfrith, whose family background is presumed to lie in Wessex, was appointed an Ealdorman in southern Mercia. Mercia was then ruled by Edward's sister Æthelflæd and her husband Æthelred. Æthelstan seems to have been appointed Ealdorman of East Anglia and other parts by King Æthelstan in about 932. The lands King Æthelstan gave him had mostly been part of the Danelaw which had only been forced out of the area after the Battle of Tempsford in Bedfordshire fifteen years earlier in 917. Æthelstan's brother Ælfstan became Ealdorman of some parts of Mercia at about the same time and both of them may have participated in King Æthelstan's invasion of Scotland in 934. Æthelstan's wife was named Ælfwynn. Her family came from the East Midlands. She was foster-mother of King Edgar of England, giving Edgar some connection with Mercia. Soon after the death of King Eadred in 955, Æthelstan left his position and became a monk at Glastonbury Abbey. It is unknown whether his move to Glastonbury was voluntary or not.

As Edgar had been brought up in what had once been the Danelaw he became a popular prince with both the middle-english (Mercians) and the Danes. In 957, the thanes of Mercia and Northumbria changed their allegiance from Eadwig to Edgar. A conclave of nobles declared Edgar as king of the territory north of the Thames. Ælfhere, Ealdorman of Mercia (died 983) was promoted by King Eadwig and faced opposition from the old guard. As noted above, the crisis came in 957, and to almost all appearances was settled by negotiation.

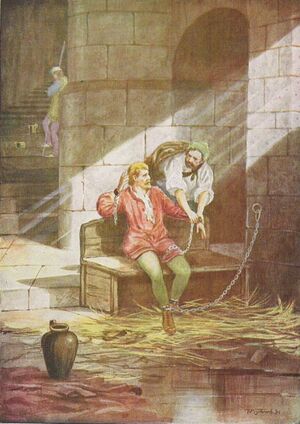

However there is some suggestion that the "negotiations" may have involved the torture of Ælfgifu. This is only mentioned in one source, Eadmer’s Life of St Oda, in which Archbishop Oda branded her on the face with a white hot iron and banished her to Ireland. When she recklessly tried to return to the kingdom she was captured at Gloucester where she was hamstrung "so that she could travel no further in pursuit of her vagrant and whorish way of life". Within days she was dead. Whether these facts about the accession of Edgar are true or later propaganda isn't known.

The English kingdom was neatly partitioned between Eadwig and his younger brother Edgar, Eadwig ruling Wessex south of the Thames, Edgar Mercia and Northumbria to the north. Ælfhere survived the crisis, abandoning Eadwig, and became Edgar's devoted supporter. Edgar was at this time around 14 years old, and would not, according to the laws at the time, achieve his majority until the age of 15. Ælfhere found himself in a powerful position, from 959 to 975 he was almost always the first witness to Edgar's charters, placing him above all others in status. One thing that this partition shows is that the idea of a "Kingdom of Mercia" still existed many years after it had supposedly been swallowed-up by Wessex.

Edgar as king

One of Edgar's first actions was to recall Dunstan from exile and have him made Bishop of Worcester and Abbot of Glastonbury Abbey, subsequently Bishop of London and later, Archbishop of Canterbury. Dunstan remained Edgar's advisor throughout his reign. The Monastic Reform Movement that introduced the Benedictine Rule to England's monastic communities peaked during the era of Dunstan. In the mid-tenth century almost all monasteries were staffed by secular clergy, who were often married. The reformers sought to replace them with celibate contemplative monks following the Rule of Saint Benedict. The movement was inspired by Continental monastic reforms, and the leading figures were Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury, Æthelwold, Bishop of Winchester, and Oswald, Archbishop of York. The English movement became dominant under King Edgar (959–975), who supported the expulsion of secular clergy from monasteries and cathedral chapters, and their replacement by monks. Æthelwold was the most extreme of the three and supposedly once commanded a monk to show his devotion by plunging his hand into a pot of boiling stew.

One notable feature of Edgar's reign was the lack of Viking raids in the period from about 954-980. 954 had seen the Northumbrians expell Eric Bloodaxe. After the expulsion of Eric the historical sources are very poor, with some indications that major figures included the Ealdormen Osulf and Oslac who held Northumbria with the leave of Eadwig and later Edgar. It is possible that Edgar had a largely "hands-off" approach to the Danelaw and that this helped to maintain peace - he certainly had a law code which promised equal treatment for the English in England and the Danes in the Danelaw, each being governed by their own laws. As for external factors Denmark was becoming christian at the time, with the conversion of Harald Bluetooth in around 960. Denmark was also going through a unification process that involved some internal conflict.

It is unclear how much power Edgar the Pacific actually had. Edgar's coronation did not happen until 973, in an imperial ceremony planned not as the initiation, but as the culmination of his reign (a move that must have taken a great deal of preliminary diplomacy). This service, devised by Dunstan and celebrated with a poem in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, forms the basis of the present-day British coronation ceremony. The symbolic coronation was an important step; other kings of Britain came and gave their allegiance to Edgar shortly afterwards at Chester. At least six kings in Britain, including the King of Scots and the King of Strathclyde, pledged their faith that they would be the king's liege-men on sea and land.

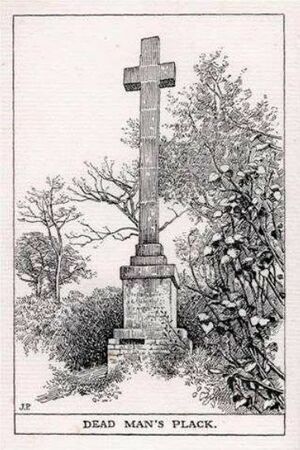

Edgar's family life was complicated. Edgar is believed to have married first Æthelflæd the White, daughter of Ordmaer, Ealdorman of the East Anglians, between 957 and 959. After Æthelflæd's death about 962, the traditional story is that Edgar abducted and married Wulfthryth of Wilton. He carried her off from the nunnery at Wilton Abbey. They lived as husband and wife at his residence in Kemsing for 2 years. It is unclear if they actually married or not, or if she had in fact been a nun. After the birth of one daughter, Wulfthryth was returned to Wilton Abbey, along with their child, and definitely now became a nun, eventually Abbess. About 964/965 Edgar married, possibly for a third time, to Ælfthryth, widow of Æthelwald, Ealdorman of East Anglia, Edgar's adopted brother. Ælfthryth was the daughter of Ealdorman Ordgar and his wife, a member of the royal family of Wessex. Legend has it that Edgar heard of Ælfthryth's great beauty and sent Æthelwald to arrange marriage for him (Edgar) but Æthelwald instead married her himself. In retaliation Æthelwald was killed 'in a hunting accident' (at the site of "Dead Man's Plack") and Edgar married her as he had wanted. It is not known if this is true or simply romantic fiction. The "Plack" carries the following inscription:

- "About the year of our Lord DCCCCLXIII upon this spot beyond the time of memory called Deadman’s Plack, tradition reports that Edgar, surnamed the peaceable, King of England, in the ardour of youth love and indignation, slew with his own hand his treacherous and ungrateful favourite, owner of this forest of Harewood, in resentment of the Earl’s having basely betrayed and perfidiously married his intended bride and beauteous Elfrida, daughter of Ordgar, Earl of Devonshire, afterwards wife of King Edgar, and by him mother of King Ethelred II. Queen Elfrida, after Edgar’s death, murdered his eldest son, King Edward the Martyr, and founded the Nunnery of Wor-well."

Ælfthryth will reappear in the story of the death of Edward the Martyr and it is likely that many of the evils associated with her were the result of later propoganda in favour of the martyred king. Also, there was a gap of two years between the death Æthelwald (whose brother remained loyal to Edgar) and Edward's marriage to his widow. Overall, it seems like the story of "Dead Man's Plack" is later fiction.

Why "Pacific"?

Edgar was associated even in the minds of his contemporaries with peace and order. Perhaps this was in contrast with what had gone before or with what was to come afterwards, but it certainly seems that he enjoyed a period free of the external threats or internal stuggles which came before and after. His laws were severe: Lantfred of Winchester makes it clear (writing in 975) that under Edgar's legal code any thief or robber would be quite savagely mutilated. It does appear that this was successful in keeping domestic crime down. Florence of Worcester wrote:

- "Wrought upon by the prudent counsels of him [Dunstan] and of other wise men, Edgar, king of the English, punished the wicked in every quarter, reduced the rebels to submission by his severity, showed favour to the just and humble, repaired and enriched God's ruined churches, removed all vanities from the monasteries of the clerks [i.e. secular clergy, as distinct from monks], collected great numbers of monks and nuns, to the glory of the Almighty Creator, and supplied more than 40 monasteries."

On the other hand his laws seem to have been inclusive in that the inhabitants of the Danelaw appear to have enjoyed a measure of consideration for their slightly different culture but also were involved in legal processes such as the witnessing of charters. It could be simply that the Vikings were at this period involved in other matters, either internal issues or raiding elsewhere. William of Malmesbury wrote:

- "... Edgar, the honour and delight of the English ... a youth of sixteen years old, assuming the government, held it for a similar period [i.e. sixteen years]. The transactions of his reign are celebrated with peculiar splendour even in our times. The divine love, which he sedulously procured by his devotion and energy of counsel, shone propitious on his years. It is commonly reported that at his birth Dunstan heard an angelic voice saying, “Peace to England so long as this child shall reign, and our Dunstan shall live.” The succession of events was in unison with the heavenly oracle – so much, while he lived, did ecclesiastical glory flourish, and martial clamour decay: scarcely does a year elapse in the Chronicles, in which he did not perform something great and advantageous to his country, in which he did not build some new monastery. He experienced no internal treachery, no foreign attack."

Edgar does seem to have maintained a navy, although the fleet of 3,600 ships which he had apparently amsssed at the time of his death does seem like an exageration taken to the point of absurdity. Viking fleets are known to comprise a hundred ships only in exceptional circumstances, and most raiding parties would be much smaller. The early English fleets were never otherwise described as so large - a fleet of 3,600 ships at Chester would have been one of the greatest collections of shipping of all time. Marc Anthony's fleet at the Battle of Actium was "only" 500-strong. In 851, an unprecedentedly large force of Danes invaded southern England, carried on, so it is said, about 350 ships. Edgar's fleet is supposedly ten times this size. Edgar is described as carrying out large-scale fleet-operations each summer, possibly including a circumnavigation of the isles, but it is difficult to see how this could be effective against any opponent who did not mass forces into a single fleet. But the Chronicles are quite clear that Edgar brought the lot to Chester:

- "geleade ealle his sciphere to Lægeceastre and þær him comon ongean vi cyningas and eallwið trywsodon þæt hi woldon efenwyrhton beon on sæ and on lande" (‘took his whole naval force to Chester, and six kings came to meet him, and all gave him pledges that they would be his allies on sea and on land’)

It could be that he is known as "the Pacific" simply because nothing much of note was recorded from during his reign. There are several possible reasons for this - he may have been on such good terms with the church that they would write little of his failures, or he may have had none. Alternatively, later Norman chroniclers as well as others who wished to show that England was conquered because it had somehow failed might have glossed over a quite successful king. Another theory is that the monastic writers he had so favoured considered his sexual exploits so outrageous that they simply had to play-up the peace and stability of his reign so as not to cast him in a negative light.

Death

Edgar died on 8 July 975 at Winchester, Hampshire. He was 33 years old. The cause of his death is not known. He was buried at Glastonbury Abbey (where Edmund was also buried), and was there venerated as a saint (pre-congregation). Edward was the eldest son of King Edgar the Peaceful but was not his father's acknowledged heir. On Edgar's death, the leadership of England was contested, with some supporting Edward's claim to be king and others supporting his younger half-brother Æthelred the Unready, recognised as a legitimate son of Edgar. The 12 year old Edward was chosen as king and was crowned by his main clerical supporters, the archbishops Dunstan of Canterbury and Oswald of York. Edgars tomb was presumably destroyed in the great fire which consumed the abbey in 1184.

Edward is murdered

In the reign of Edward the Martyr (c. 962 – 18 March 978), his support for Dunstan's Benedictine reform movement provoked the anger and envy of those who had seen the Church as a way to gain wealth and prestige. The ascetic life and the importance of monasticism promoted by Dunstan and his colleagues were not to their liking, and so they looked for – and found – other friends in high places. Ælfhere was a leader of the anti-monastic reaction and a close ally of Edward's stepmother Queen Dowager Ælfthryth. Civil war almost broke out over the disputed succession and in the anti-monastic reaction the nobles took advantage of Edward's weakness to dispossess the Benedictine reformed monasteries of lands and other properties that previous King Edgar had granted to them. Edgar's death was not without portents, after recording Edward's succession, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports that a comet appeared:

- "Then too was seen, high in the heavens, the star on his station, that far and wide wise men call – lovers of truth and heav'nly lore – ‘cometa’ by name. Widely was spread God's vengeance then throughout the land, and famine scour'd the hills. May heaven's guardian, the glory of angels, avert these ills, and give us bliss again; that bliss to all abundance yields from earth's choice fruits, throughout this happy isle."

Æþelræd was the son of Edgar and his second (or perhaps third) wife, Queen Ælfthryth. Æþelræd came to the throne at about the age of 12, following the assassination of his older half-brother, Edward the Martyr. His brother's murder was carried out by supporters of his own claim to the throne, although he was too young to have any personal involvement. Ælfthryth appeared as a stereotypical bad queen and evil stepmother in many medieval histories, where she was generally believed to have been involved in the murder of Edward. The earliest chronicle texts only state that Edward was killed, by the time of later chronicles it was claimed that Ælfthryth plotted the murder and eventually that she did the deed herself. Modern historians note that Edward in life was not a saintly figure and offended many people.

After the death of Edward (the Martyr) in 978, Æthelred was not yet old enough to rule on his own and Ælfthryth acted as regent. Æthelred's cause was led by his mother but included Ælfhere, Ealdorman of Mercia. Edward the Martyr's story did not end with his death. His bones were first moved in 981 to a convent in Shaftsbury, then to the Abbey there in 1001. At the dissolution his bones were hidden, only to be found again in 1931, spending the next half-century in a bank vault as neither the Church of England or that of Rome wanted them. In 1984, they were placed in a shrine at the Russian Orthodox Cemetery at Brookwood, Surrey - the only English ruler buried in an Orthodox shrine.

Despite the later protests of the church chronicles, there appears to have been no real outcry over the murder of Edward. Only Dunstan seems to have spoken out, and then only to issue a dire prophecy that "the country would pass into the hands of a stranger" - even that may well be a later concoction. The historian Æthelweard, himself closely involved with the key players, wrote that:

- "Edward's earthly kin would not avenge him, but left the vengance to his Heavenly Father"

Perhaps the magnates believed that after the relatively peaceful reign of Edgar anything was better than a civil war.

Boy King Æþelræd

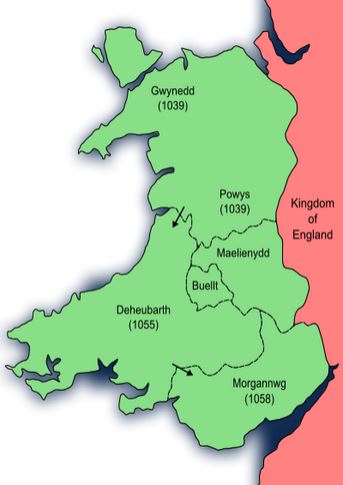

As the ealdorman of Mercia, Ælfhere was concerned with relations with the Welsh princes. The Mercian tradition was that this meant war. Wars in Wales gave opportunities for fame, and for booty to be distributed to allies and kinsmen. A campaign in 983 by Ælfhere against Brycheiniog and Morgannwg, with the aid of the Welsh king Hywel ap Ieuaf, is recorded by the Annales Cambriae.

England had experienced a period of peace after the reconquest of the Danelaw in the mid-10th century by King Edgar, Æþelræd's father. However, beginning in 980, when Æþelræd had been king for two years and could not have been more than 14 years old, small companies of Danish adventurers carried out a series of coastline raids against England. Hampshire, Thanet and Cheshire were attacked in 980 and other raids followed. The 980 raid is recorded in the "C manuscript" of the Anglo Saxon Chronicle in the following terms:

- "..and the same year Cheshire was ravaged by a northern naval force"

The decline of the Chester mint has long been attributed to the Viking raid on Cheshire in 980. Three of the four Anglo-Saxon coin hoards found in the city, those from Castle Esplanade, Pemberton's Parlour, and Eastgate Street, have been assigned to roughly the same period and were originally interpreted as being linked to that raid. However it now seems that they were deposited 965-970, before the Viking raid. The city's relatively depressed state was indicated by the low output of its mint in the 980s and early 990s. This was a time of a certain level of national disorder following the death of Edgar the Pacific.

A few years later in 991, a Danish fleet sailed up the Blackwater river in Essex, and then decisively defeated the county’s defenders at the Battle of Maldon, all Æþelræd worst fears appeared to be coming true as the kingdom tottered under the ferocity of the onslaught. Æþelræd tried to buy the Vikings off. In 997 the inevitable happened and the Danes returned, some from as close as the Isle of Wight where they had settled completely unimpeded. Over the next four years the southern coasts of England were devastated and the English armies powerless whilst Aethelred desperately sought some kind of solution. At the same time, the country was in the grips of “millenarian” fever, as thousands of Christians believed that in the year 1000 (or thereabouts) Christ would return to earth to resume what he had started in Judaea.

Æþelræd had started his reign surrounded by councilors and advisors who had considerable experience dating back to the time of Edgar. Many of these magnates would live at least into the next decade before starting to die off or retire from public life. During this period the Viking raids were relatively few, but it may be no co-incidence that as his older advisors began to fall away the intensity of the raids increased.

Prophets of Doom

Approaching the year 1000 (or 1001 given there was no "year zero")) speculation as to the closeness of the End of the World was rife. It was generally considered forbidden to speculate as to the precise timing of the Day of Judgement, something which had caused problems for Bede. This did not stop priests speculating about the coming of the Antichrist, who was expected to arrive any day. In 971, a preacher had begun by stating that speculation was forbidden before, in the next breath, launching into a prediction that "Doom was Nigh":

- "For so veiled by secrecy is the end of days, that no one in the entire world, no matter how holy, nor anyone in heaven, except the Lord alone, has ever known when it will come. The end cannot be long delayed.. ..only the coming of the accursed stranger, Antichrist, who is yet to appear on the face of the earth, is still awaited."

"Fire and brimstone" sermons were commonplace and Wulfstan wrote with vivid rhetorical force about the unpleasantries of Hell (notice the alliteration, parallelism, and rhyme):

- "Wa þam þonne þe ær geearnode helle wite. Ðær is ece bryne grimme gemencged, & ðær is ece gryre; þær is granung & wanung & aa singal heof; þær is ealra yrmða gehwylc & ealra deofla geþring. Wa þam þe þær sceal wunian on wite. Betere him wære þæt he man nære æfre geworden þonne he gewurde". - "Woe then to him who has earned for himself the torments of Hell. There there is everlasting fire roiling painfully, and there there is everlasting filth. There there is groaning and moaning and always constant wailing. There there is every kind of misery, and the press of every kind of devil. Woe to him who dwells in torment: better it were for him that he were never born, than that he become thus."

The Viking raids played straight into the hands of these prophets of doom. Wulfstan's five eschatological homilies seem to have been among the earliest sermons he wrote, and although none of his later works address this theme in their entirety, the subject is one that occupied him throughout his career. He was convinced, as were many of his contemporaries, that the end of the world was near, interpreting both the depredations of the Vikings and a perceived deterioration in morality among the English to mean that the reign of the Antichrist was at hand. Wulfstan’s messages to the English people are typically full of gloom:

- "For it is clear and manifest in us all that we have previously transgressed more than we have amended, and therefore much is assailing this people. Things have not gone well now for a long time at home or abroad, but there have been devastation and famine, burning and bloodshed in every district again and again."

The murder of an anointed king Edward in 978, perhaps already "Edward the Martyr" in the words of some, was no doubt seen as an ominous sign of the last times being at hand. Rumours spread that his body had been dragged by his bolting horse and flung into a bog. A column of fire was said to have marked the spot where his body lay. Portents included a "great bloody cloud rising out of the north and covering the heavens" even as the young Æþelræd was being crowned. The year 989 had seen the return of Halley's comet. Eilmer of Malmesbury, the fanous "flying monk" recorded in Chester's Polychronicon, may have seen Halley in 989, as he wrote of it in 1066:

- "You've come, have you? ... You've come, you source of tears to many mothers, you evil. I hate you! It is long since I saw you; but as I see you now you are much more terrible, for I see you brandishing the downfall of my country. I hate you!"

From tree-rings of 993/4 there are signs of a recent major Coronal Mass Ejection which would have caused significant auroral displays (as recorded in 992) and no doubt contributed further to the worries of those watching the skies for portents of doom. This was similar to that of 774 which was also associated with "dragons" being seen in the sky.

The papacy at this time was a complete mess, with frequent conflicts between popes and anti-popes. In the year 1000 itself the papal throne was occupied by Sylvester II, a Frenchman originally known as Gerbert of Aurillac. He was something of a ray of hope: evidently a skilled mathematician,he endorsed and promoted study of Arab and Greco-Roman arithmetic, mathematics, and astronomy, reintroducing to Europe the abacus and armillary sphere, which had been lost to Latin Europe since the end of the Greco-Roman era. He is said to be the first to introduce in Europe the decimal numeral system using Hindu–Arabic numerals and to have promoted the use of the abbacus. Unfortunately, he was soon forced to flee by John Crescentius and a series of puppet popes followed. Later scholars evidently found it difficult to believe that the papal throne could be occupied by anyone as rational as Gilbert and gleefully retold various legends about Gilbert having seduced a philosophers daughter to steal a book of sorcery and then make a deal with the devil - thus guaranteeing himself both the top job and a (completely fictitious) grisly end. Rumours also circulated (many from William of Malmesbury) that Gilbert had constucted a talking "brazen head" (Walter Map replaces it with what appears to be a Succubus). This head (or Succubus) had the name "Meridiana" and seems to be a very distorted reference to an armillary sphere, or some other form of navigational instrument.

Danegeld

An English payment of 10,000 Roman pounds (3,300 kg) of silver was first made in 991 following the Viking victory at the Battle of Maldon, when Æthelred was advised by Sigeric the Serious, Archbishop of Canterbury, and the aldermen of the south-western provinces to buy off the Vikings rather than continue the armed struggle. In recent years some doubt has been cast on whether Sigeric actually made the suggestion, the consequences of which appear to have virtually bankrupted him. Rudyard Kipling would later write:

- " ..And that is called paying the Dane-geld; But we’ve proved it again and again, That if once you have paid him the Dane-geld, You never get rid of the Dane."

The twerm "Danegeld" did not appear until the late eleventh century. It was actually the much later Norman administration who referred to the tax as Danegeld. In Anglo-Saxon England tribute payments to the Danes was known as "gafol" and the levy raised to support the standing army, for the defense of the realm, was known as heregeld (army-tax). Further payments were made in 1002, and in 1007 Æthelred bought two years peace with the Danes for 36,000 troy pounds (13,400 kg) of silver. In 1012, following the capture and murder of the Archbishop of Canterbury, and the sack of Canterbury, the Danes were bought off with another 48,000 troy pounds (17,900 kg) of silver. It is estimated that the total amount of money paid by the Anglo-Saxons amounted to some sixty million pence. More Anglo-Saxon pennies of this period have been found in Denmark than in England.

One of Æthelred's proposed solutions to the problem of the Danes bordered on the apocalyptic.

Genocide

On Friday, November 13th, A.D. 1002, Æthelred Unræd, ruler of the English, "ordered slain all the Danish men who were in England", according to a royal charter. Æthelred’s order led to what is known as the St. Brice’s Day Massacre, named for the saint’s feast day on which it fell. The event has long been cloaked in mystery and misinformation. Archaeology, so far, has had little to offer in the matter of what actually happened and how many people died that day - although there has possibly been quite clear confirmation of some local events from a dig in Oxford and another near Weymouth.

Rumours of a Viking coup may have been circulating for some time. According to the "C", "D" and "E" texts of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a somewhat biased tenth-century account:

- "..it was told the king, that they would beshrew him of his life, and afterwards all his council, and then have his kingdom without any resistance."

However this is not evidence of a national viking plot. The massacre in Oxford was justified by Æthelred, showing no remorse, in a royal charter of 7th December 1004 explaining the need to rebuild St Frideswide's Church (now Christ Church Cathedral):

- "For it is fully agreed that to all dwelling in this country it will be well known that, since a decree was sent out by me with the counsel of my leading men and magnates, to the effect that all the Danes who had sprung up in this island, sprouting like cockle amongst the wheat, were to be destroyed by a most just extermination, and thus this decree was to be put into effect even as far as death, those Danes who dwelt in the afore-mentioned town, striving to escape death, entered this sanctuary of Christ, having broken by force the doors and bolts, and resolved to make refuge and defence for themselves therein against the people of the town and the suburbs; but when all the people in pursuit strove, forced by necessity, to drive them out, and could not, they set fire to the planks and burnt, as it seems, this church with its ornaments and its books. Afterwards, with God's aid, it was renewed by me."

The skeletons of 34 to 38 young men, the majority aged 16 to 25, were found during an excavation at St John's College, Oxford, in 2008. Chemical analysis carried out in 2012 by Oxford University researchers suggests that the remains are Viking based on isotopes found in tooth enamel; older scars on the bones provide evidence that they were professional warriors. It is thought that they were stabbed repeatedly and then brutally slaughtered. Charring on the bones is consistent with historical records of the church burning. However they may not be victims of a wide-ranging massacre, but instead the bodies of a viking raiding party. The isotopic analysis indicates that the bones were of men who had grown-up on a diet with a significant element of sea-food, something that would have been rare in Oxford. Consequently, the evidence seems to suggest that they were not second or even later generation Danes who had settled in the city, but relatively recent arrivals.

In 2009 another mass burial was found on the Dorset Ridgeway containing 51 decapitated individuals. The radiocarbon dates place the burial between 970-1025, that would allow for this massacre to also be tied to St Brice’s day 1002. Tooth enamel analysis identifies the victims as Scandinavian. Unlike Oxford, however, where evidence of injuries points to the men being warriors and likely dying while fighting (or fleeing), the bodies at Dorset show few injuries, either pre-existing or contemporary with execution. This suggests that the victims were not warriors, and also indicates that they were executed by beheading with little by way of struggle or resistance.

One of those killed (some claim at at Oxford), apparently, was Gunnhild, the sister of the Danish king Swein Forkbeard, which was taken by later chronicles to have sharpened the latter’s hostility. The later chronicle-writers would have us believe that the following summer Swein sacked Exeter. Swein then went on to harry Wessex and destroy Wilton. However there are serious difficulties with this version of events mostly derived from William of Malmesbury writing around 1140: there is no Danish record of Swein having a sister called Gunnhild. Even by the time of William of Jumièges’ Gesta Normannorum Ducum, written around 1070 the "massacre" had become an outrageous act of genocide:

- "But while, as we learnt above, under such a famous ruler [Richard, duke of Normandy] the prosperity of Normandy grew, Aethelred, king of the English defiled a kingdom that had long flourished under the great glory of most powerful kings with such a dreadful crime that in his own reign even the heathens judged it as a detestable, shocking deed. For in a single day he had murdered, in a sudden fury and without charging them with any crime, the Danes who lived peacefully and quite harmoniously throughout the kingdom and who did not at all fear for their lives."

A troubled country

It is possible that the later chroncles greatly exaggerated the scope of the massacre to cast Æthelred in a very poor light and provide Norman propaganda. Apart from the two finds described above there is little evidence of a widespread slaughter of the Danish population and it would probably have been impossible for this to have occurred in the Danelaw, where the proportion of the population with Scandinavian ancestry must have been quite large. The later Norman propaganda has Æthelred's mother instigating the murder of her "saintly" stepson and Dunstan predicting that that the country and Æthelred would be destroyed as a consequence. These legends backed up the Norman position that the English rulers had become corrupt and deserved to be overthrown. Æthelred is variously stated to have "grasped the throne by the shedding of his brothers blood" (Æthelred was aged about 12 at the time), been indolent and weakly tried to pay the Vikings off with heavy taxation, and even resorted to an attempt at genocide - the hint being that at Oxford he even had slain those who had sought the sanctuary of the church.

At the same time, the inhabitants of Æthelred's England must have looked back on the days of Edgar the Pacific as an idylic time of peace and prosperity. In Edgar's reign there was a reduction in taxation and the nobility enjoyed economic benefits. The Church prospered with a weeding-out of corruption and the "end of days" gloom of the approaching millennium had not yet descended on the country. Edgar had regulated the currency placing it under centralised control which was now providing a standardised coinage that was widely accepted for foreign trade, probably at a predicatable value. The wealth of England was possibly one factor which attracted the attention of Scandinavians during the reign of Æthelred.

Edgar's laws were seen as just and practical, and compared with the surrounding countries there was relative peace. On the continent the disintergrating remnants of the Carolingian Empire were in an almost permanent state of civil strife, if not all-out civil war. This meant that armed forces were in a state of readyness. In England it may well have been that the military was far less strong. It is known that Æthelred employed Scandinavian mercenaries, a circumstance that frequently heralds a disaster. One of the mercenaries originally on the Viking side was Thorkell the Tall a prominent member of the the elite Jomsviking order who were exceptionally well trained and well organised. Thorkell would play an important part on both sides of the conflict.

Worse still Æthelred seems to have engaged in considerable political infighting. One of his political "enforcers" was Eadric Streona ("the grasper"). Eadric's character was the subject of very clear assessments by later chroniclers:

- "..he was a man, indeed, of low origin, but his smooth tongue gained him wealth and high rank, and, gifted with a subtle genius and persuasive eloquence, he surpassed all his contemporaries in malice and perfidy, as well as in pride and cruelty." — John of Worecester, Chronicon ex Chronicis

- "This fellow was the refuse of mankind, the reproach of the English; an abandoned glutton, a cunning miscreant; who had become opulent, not by nobility, by specious language and impudence. This artful dissembler, capable of feigning anything, was accustomed, by pretended fidelity, to scent out the King’s designs, that he might treacherously divulge them." — William of Malmesbury, Gesta regum Anglorum

Eadric was one of at least eight children and had relatively humble beginnings: his father Ethelric attended the court of King Ethelred the Unready, but was of no great significance and is not known to have had any titles. Even before becoming an ealdorman, Eadric seems to have acted as Ethelred's enforcer; in 1006 he instigated the killing of the Ealdorman of York, Elfhelm:

- "The crafty and treacherous Eadric Streona, plotting to deceive the noble ealdorman Ælfhelm, prepared a great feast for him at Shrewsbury at which, when he came as a guest, Eadric greeted him as if he were an intimate friend. But on the third or fourth day of the feast, when an ambush had been prepared, he took him into the wood to hunt. When all were busy with the hunt, one Godwine Porthund (which means the town dog) a Shrewsbury butcher, whom Eadric had dazzled long before with great gifts and many promises so that he might perpetrate the crime, suddenly leapt out from the ambush, and execrably slew the ealdorman Ælfhelm. After a short space of time his sons, Wulfheah and Ufegeat, were blinded, at King Æthelred’s command, at Cookham, where he himself was then staying." - Worcester Chronicle.

Eadric was married to Æthelred's daughter Edith by 1009, thus becoming his son-in-law. Eadric was appointed Ealdorman of Mercia in 1007.

As an ealdorman, Eadric played an important role in the affairs of the kingdom. In 1009 he negotiated with marauding Vikings to save the life of Archbishop Ælfheah of Canterbury, which proved to be unsuccessful - Ælfheah became the first Archbishop of Canterbury to die a violent death. Eadric also continued to organise the killings of prominent nobles — supposedly upon orders of the king. Eadric was not the only treacherous actor in Æthelred's world. In 992, it appears that an ealdorman named Alfric changed sides just before a naval battle. His reward was to have his son blinded on Æthelred's orders.

Mercia in 1007

The "C" manuscript of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle has the following entry for the year 1007:

- "In this year also Eadric was appointed ealdorman over all the Mercian kingdom" (geond eall myrcena rice)

This is odd. By this time the "kingdom" of Mercia is supposed not to have existed as a political entity for around a century at least. Apart from brief reappearance possibly in some form under Æthelflæd and Edgar the Pacific. There are other indications that Mercia was still considered as a political entity. A charter refers to:

- "ealle ða ðegnas ðe þær widan gegæderode wæron ægðer . ge of Westsexan . ge of Myrcean . ge of Denon . ge of Englon" (all the thegns who from far and wide were gathered there, both West Saxon and Mercian, English and Danish)"

In this reference Wessex/Mercia form a pairing as do English/Danish. One can only speculate about the loyalties of Mercia, and hence of Chester in 1007. Chester had clearly been an important city long after its decline as a major Roman base, possibly maintaining some status as an ecclesiastical center prior to the Battle of Chester in 616. Offa and the Mercians almost certainly used it as a base for military operations on the Welsh borders (Coenwulf died in 821 at Basingwerk near Holywell), but there would have been extensive trade with Wales, especially of salt. There would also have been trade with Ireland. The Danish invasions brought a division into the Danelaw along a line which stretched from Chester to London: effectively following the Roman Watling Street. Plegmund almost certainly lived nearby. Alfred apparently fought Vikings at Chester. Alfred's son Edward (c. 874 – 17 July 924) regained much of the lost territory with the aid of his warlike sister who rebuilt and extended the walls of Chester, then Edward died at Farndon after dealing with a revolt in Chester. Next came Æþelstān (c. 894 – 27 October 939) who may have fought the Battle of Brunanburh near Chester. Chester was an important base in 942 when there was collusion between the Welsh and the Scandinavian kingdom of York during King Edmund's campaign against the latter. Ingimund and his people were Vikings who had settled in the Wirral, making Chester a very cosmopolitan city, with the Chester Mint, staffed by some Scandinavian moniers which also supposedly bashed-out coins for the Welsh. Chester may justly claim to have been the most prolific mint town in the whole country in the second quarter of the tenth century.

Viking settlers had given their "-by" place-names to Norse settlements in Wirral and South Lancashire, whose place-names are familiar as West Kirby, Frankby, Greasby, Pensby, Formby, Crosby, Helsby and other towns. The religious connection had continued with the growth of what were to become St Johns and the Cathedral. Edgar the Pacific had chosen Chester for the confirmation of his rule of all England. Edgar's cause had been promoted by Mercians including Ælfhere, the Ealdorman of Mercia who fought in Welsh wars before his death in 983. A large part of the inhabitants of the Danelaw were Scandinavians, now descended from settlers who had arrived several generations back and largely converts to christianity. They may well have disagreed strongly with Æþelræd's policy of genocide against the Danes. There was probably an increase of Danish influence in Chester, evidence for which can be found in Domesday Book, and this may have been a result of the opening up of trade relationships on a wider scale. Not only do we later find an abundance of Scandinavian names, which may have been the result of extensive colonisation dating from the time of Canute, but Danish legal forms and standards of measurement. For example, it is stated that at Handbridge there were three carucates of land, the Norse term which stands out among the Saxon hides. It also appears that Chester was governed by twelve "indices civitatis", or Law men, a form of local Government which is only otherwise found on the eastern side of England.

As will be seen by subsequent events, within ten years the men of Mercia would refuse to fight the Danes and to some extent abandon the English to their fate.

Swein Forkbeard Invades

Sweyn acquired massive sums of Danegeld through his raids. In 1013, he is reported to have personally led his forces in a full-scale invasion of England. The contemporary Peterborough Chronicle (part of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle) states:

- "..before the month of August came king Sweyn with his fleet to Sandwich. He went very quickly about East Anglia into the Humber's mouth, and so upward along the Trent till he came to Gainsborough. Earl Uchtred and all Northumbria quickly bowed to him, as did all the people of the Kingdom of Lindsey, then the people of the Five Boroughs. He was given hostages from each shire. When he understood that all the people had submitted to him, he bade that his force should be provisioned and horsed; he went south with the main part of the invasion force, while some of the invasion force, as well as the hostages, were with his son Cnut. After he came over Watling Street, they went to Oxford, and the town-dwellers soon bowed to him, and gave hostages. From there they went to Winchester, and the people did the same, then eastward to London."

The Londoners put up a strong resistance, because King Æthelred and Thorkell the Tall, a Viking mercenary leader who had "defected" to Æthelred, personally held their ground against him in London itself. Sweyn then went west to Bath, where the western thanes submitted to him and gave hostages. The Londoners then followed suit, fearing Sweyn's revenge if they resisted any longer. King Æthelred sent his sons Edward and Alfred to Normandy, and himself retreated to the Isle of Wight, and then followed them into exile. Olaf II Haraldsson (Óláfr Haraldsson c. 995 – 29 July 1030) aka "Olaf the Fat" of St Olave in Chester may have been involved at this stage of the war.

On Christmas Day 1013 Sweyn was declared King of England. Based in Gainsborough, Lincolnshire, Sweyn began to organise his vast new kingdom, but he died there on 3 February 1014, having ruled England for only five weeks. Sweyn's elder son, Harald II, succeeded him as King of Denmark, while his younger son, Cnut, was proclaimed King of England by the people of the Danelaw. However, the English nobility sent for Æthelred, who upon his return from exile in Normandy in the spring of 1014 managed to drive Cnut out of England. Cnut soon returned and became king of all England in 1016, following the deaths of Æthelred and his son Edmund Ironside. England had finally been conquered by the Scandinavians.

Cnut built on the existing English trend for multiple shires to be grouped together under a single ealdorman, thusly dividing the country into four large administrative units whose geographical extent was based on the largest and most durable of the separate kingdoms that had preceded the unification of England. The officials responsible for these provinces were designated earls, a title of Scandinavian origin already in localised use in England, which now everywhere replaced that of ealdorman. Wessex was initially kept under Cnut's personal control, while Northumbria went to Erik of Hlathir, East Anglia to Thorkell the Tall, and Mercia remained in the hands of the treacherous Eadric Streona.

The House of Leofric

The early "earl's" of Mercia include Ælfhere, the Ealdorman of Mercia who died in 983 and was a supporter of Edgar the Pacific. Following the partition of the kingdom, Edgar's stepfather Æthelstan Half-King retired from political life, leaving Ælfhere as the chief ealdorman in Edgar's northern kingdom. From 959 to 975 he was almost always the first witness to Edgar's charters. The Life of Oswald of Worcester written by Abbot Byrhtferth of Ramsey refers to Ælfhere by the impressive title "princeps merciorum gentis" — prince of the Mercian people, last used in the days of Æthelflæd and Ælfwynn of Mercia — and as a witness to Oswald's charters he is called "ealdorman of the Mercians. He would most likely have been present in 973 when Edgar made his noted voyage on the River Dee at Chester. Upon the death of Edgar, Ælfhere was a supporter of Æthelred rather than Edward the Martyr. However is is credited with having the remains of the murdered king reburied at Shaftesbury Abbey. Whether Ælfhere wished to publicly disassociate himself from the killing of Edward, or to assuage a guilty conscience can only be conjectured — he certainly profited from Edward's death.

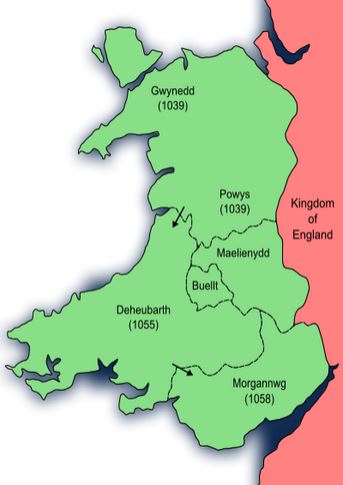

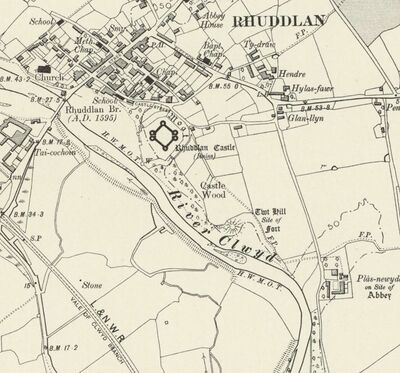

In 978, the very year that Æthelred became king, English troops possibly supplied by Ælfhere of Mercia were deployed on the Lleyn Peninsula on behalf of King Hywel ab Ieuaf of Gwynedd in order to prevent his uncle, Iago ab Idwal, invading with Viking allies from Dublin. Hywel is first recorded as accompanying Iago to Chester to meet King Edgar of England in 973. It would therefore appear that Ælfhere was possibly carrying out his treaty obligations. A campaign in 983 by Ælfhere against Brycheiniog and Morgannwg, also with the aid of the Welsh king Hywel ap Ieuaf, is recorded by the Annales Cambriae. However, in 985 (after the death of Ælfhere) Hywel's English allies turned on and killed him, possibly alarmed by his growing power. He was succeeded by his brother Cadwallon ap Ieuaf, who had not been on the throne long when Gwynedd was annexed by Maredudd ap Owain of Deheubarth. Ælfric Cild (fl. 975 – c. 985)[1] was a wealthy Anglo-Saxon nobleman from the east Midlands, and succeded to become ealdorman of Mercia between 983 and 985, and was possibly brother-in-law to his predecessor Ælfhere. He was also associated with the monastic reformer Æthelwold, bishop of Winchester. Ælfric was not able to retain his new position for very long, however. Early in the year 985, a royal council was convened at Cirencester and Ælfric was driven out of the country on account of treason. The nature of the accusation is unknown and it is not clear how this fits in with the English turning on Hywel ap Ieuaf. It is not known when Ælfric died or what became of him in exile. The cartulary-chronicle Historia Ecclesie Abbendonensis written in the 12th century claims that he left for Denmark, assembled a band of Viking soldiers and returned to attack England. However, the text may have confused Ælfric Cild with a namesake. The title did not pass to Ælfric's son Ælfwine who appears to have died fighting in the Battle of Maldon in 991. Clearly by fairly early in his reign Æthelred support may have been weakened by a combination of the death of supporters and possible treason or treaty breaking.

Eadric was appointed the Ealdorman of Mercia in 1007. The position having been vacant since 985.

Leofwine

Leofwine (died in or after 1023) is said to have been appointed Ealdorman of the Hwicce by King Æthelred II of England in 994. Other versions have him appointed to Mercia at that time. The chronicles are very confused over who was appointed to Mercia when. This is perhaps not surprising given that the Danes were now attacking with increased frequency (see chronology below). A supposed ancestry of Leofwine is found in the Genealogia Fundatoris of Coventry Monastery, but this is considered suspect by many historians having been only written no earlier than the reign of King John and being unconfirmed by other sources. It is possible that he was distantly related to Ælfhere, a previous Ealdorman of Mercia, but this is also unconfirmed.