Database changes have finished applying - please report any issues you're (still) seeing to support@shoutwiki.com.

Plegmund

Plegmund (or Plegemund; died 2 August either 914 or 923) was a medieval English Archbishop of Canterbury to Alfred the Great. He is reputed to have been a hermit near Chester before he became archbishop in 890 and would possibly have been at Chester when Werburgh was translated there. As archbishop (under a vast number of different Popes), he reorganised the Diocese, creating many new sees, and worked with other scholars in translating religious works: he may have been involved in the education of Edward the Elder, Æthelflæd and Æþelstān. During his life he made a journey to Rome which in the circumstances was incredibly dangerous and brought about by the most peculiar of events, but managed to return safely. Plegmund may well have lived to over seventy. He was canonised after his death, but attracted no hagiographer and his cult was never particularly strong. His precise role in the establishment of the cult of Werburgh at Chester remains to be fully explored. Locally, he is best known for his well, which has a curious story of its own as regards its restoration. Despite his long tenure as Archbishop and his reform of the church the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle hardly gives him the mention one might expect.

Early Life

Little is known of the early life of Plegmund except that (according to Asser's Vita Ælfredi regis Angul Saxonum) he was of Mercian descent. A later tradition, as recorded by Gervase of Canterbury (c1141 – c1210) stated that Plegmund lived "an eremetic life" at Plemstall in Cheshire in his "Actus Pontificum Cantuariensi":

- "Plegemundus, vir admodum religiosus et sacris litteris nobiliter instructus, in Cestria insula quae dicitur ab incolis Plegemundesham, per annos plures heremeticam duxerat vit" ("Plegmund a most religious man and nobly learned in sacred literature, had for many years led an ermetic life on an island in Cheshire called Plegmundesham by the locals")

Much of the historical evidence agrees with the association with Plegmundesham being Plemstall, just north of Chester and site of "Plegmund's Well". But there is a tension between his description as a long-term "hermit" and his appointment as an Archbishop. Possibly the meaning of "eremetic" is that he lived an austere life or possibly that he took frequent retreats.

The State of Mercia

At the time of Plegmund's birth (which may be roughly estimated at circa 850) his native Mercia was in a state on the brink of collapse. For most of the 8th century, Mercia had been dominant among the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms south of the river Humber, but with the death of Offa in 786, and his son Ecgfrith a mere 141 days later Mercia began to totter. Successor Coenwulf died in 821 at Basingwerk near Holywell, probably while making preparations for a campaign against the Welsh that took place under his brother and successor, Ceolwulf, the following year. Within two years (in 823) Ceolwulf had been deposed by Beornwulf who lasted a mere three years before death in battle. Ludeca, who followed, lasted less than a year before also dying in battle. Wiglaf was King of Mercia from 827 to 829 when he was overcome by Ecgbert (who raided as far as Chester and is commemorated at the Town Hall) and again from 830 until his death in 839. Beorhtwulf was next, and now faced a Viking threat as well as the Welsh and his own rival Mercians.

The first monastery to be raided was in 793 at Lindisfarne, off the northeast coast. Monasteries and minster churches were popular targets as they were wealthy and had valuable objects that were portable. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records Viking raids in 841 against the south and east coasts of Britain, including the Mercian province of Lindsey, centred on modern Lincoln. The city of London, chief centre of Mercia's trade, was attacked the following year. The Chronicle states that there was "great slaughter" in London, and large coin hoards were buried in the city at this time and probably severe economic consequences elsewhere. But not all of Mercia was attacked, by 850, with the recent arrival of the remains of Wigstan, the abbey at Repton, far inland, had developed into a major religious center - with a noted crypt filled with Mercian relics. Possibly a similar crypt existed at the Amphitheatre site at Chester.

Repton has an association with hermits, islands and missionary monks through Guthlac of Crowland (c674 – 3 April 715), who as a young man, fought in the army of Æthelred of Mercia. In 699 Guthlac sought to live the life of a hermit, and moved out to the island of Croyland in the south Linconshire Fens. Guthlac built a small oratory and (according to tradition) cells in the side of a plundered barrow on the island, and he lived there until his death on 11 April in AD 714. His early biographer Felix asserts that Guthlac could understand the "strimulentes loquelas" (sibilant speech) of the British-speaking demons who haunted him there, only because Guthlac had spent some time in exile among Celtic Britons. Much like Plegmund, Guthlac moved between societal roles and rank, between regions and languages.

In 851, a Viking army landed at Thanet, then still an island, and over-wintered there. A second Viking force of 350 ships is reported by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle to have stormed Canterbury and London, and to have "put to flight Beorhtwulf, king of Mercia, with his army". Burgred became king of Mercia in 852. In 853 Burgred sent messengers to Æthelwulf, king of the West Saxons, to help him subjugate the Welsh and restore the traditional Mercian hegemony. Twelve years after Burgred's success against the Welsh, in 865, the "Great Heathen Army" arrived. Following its successful campaigns against East Anglia and Northumbria it advanced through Mercia, arriving in Nottingham in 867. Burgred then appealed to his brothers-in-law King Æthelred of Wessex and his brother Alfred for assistance against them. The armies of Wessex and Mercia did no serious fighting as Burgred paid the Danes off. No longer did the Vikings continue mere coastal attacks. In 874 the march of the Vikings from Lindsey to Repton drove Burgred from his kingdom after they sacked Tamworth, the Mercian "royal centre". Tamworth would remain a ruin until 913. Burgred retired to Rome and died there. He was buried, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, "in the church of Sancta Maria, in the school of the English nation" (now Ospedale di Santo Spirito in Sassia). Meanwhile the Vikings consolidated their hold over large parts of Mercia.

It is unknown whether Plegmund was actually from near Chester, whether he had moved for the purpose of study or whether he was driven from elsewhere by the Viking raids. He may have enjoyed a fairly peaceful life during the early reign of Burgred. In 855 king Æthelwulf of neighbouring Wessex went on pilgrimage to Rome, taking a year over the trip, and taking his youngest son (later Alfred the Great) with him. Historians are divided over the reasons for this trip - Æthelwulf may have been overly pious or seen himself as the target of divine wrath (in the form of Vikings). Assuming Plegmund was born about 850, then by the time he was twenty the great abbeys of Mercia were being pillaged and burned by the Vikings: a period of ruination that would continue for ten years. By around 870 the dioceses of Lindsey, Elmham and Dommoc had ceased to exist and Hexham, Leicester and York were shortly to follow.

The Early Church

There are said to be records of a church at Plemstall as far back as the 7th century, when the River Gowy used to flood the surrounding land and the locality (barely elevated) was known as the "Isle of Chester". A legend, perhaps of the 5th or 6th century, tells of a shipwrecked fisherman who, on finding refuge here, built a church as an act of thanksgiving, dedicating it to St Peter the fisherman. It is not clear how the suggestion of an early church and a "hermitage" fit together. It has been suggested that Plegmund himself was the fisherman but that seems to be a confusion between two separate sources. Also, there is a weak suggestion in Asser that Plegmund was more than a hermit when before he was selected by Alfred: Asser says that Alfred summoned four distinguished Mercian clerics and showered them with honours and entitlements in Wessex, "not counting those which Archbishop Plegmund and Bishop Werferth already possessed in Mercia".

Although the surrounding land has been drained, the church still stands in a fairly isolated location. Once called "Plegmundeshamm" (which may be translated as "Plegmund's hemmed-in place in water meadows"), later Plemondstall, it is now Plemstall. There are some few remains of a 12th century church, but the present sandstone building of St Peter is mainly 15th century. The tower was added in 1826, replacing a wooden belfry. Most of the original Stained Glass has gone, but there are said to be fragments from the 14th century (they may possibly be slightly later). In a display case in the north aisle are (or were) a Breeches Bible of 1608, a King James Bible of 1611, a folio edition of the bible printed by Edward Whitchurche in 1549, a black letter bible of 1549 and a King James Bible of 1623. The strikingly macabre c.1670 century tomb of the Hurleston family is located at the rear of St. Peter's church. Pevsner speculated these skeletal representations were figures of Adam and Ever (by counting ribs), others have speculated further on this (see links below) and even suggested that the arrows are pointing to the groin and heart of the figures to represent the death of an infant.

One noted incumbent in the latter part of the 18th century, was the Rev John Baldwin of Hoole. His son Thomas Baldwin, who was also ordained, took part in a famous balloon flight in 1786. He took off from Chester Castle. Another noted incumbent was the Rev. Joseph Hooker Toogood (rector 1907-46). Pevsner records the war memorial was carved by Toogood and in fact the industrious Toogood was responsible for improvements to the chancel screen, a new altar, the reredos and panelling for the sanctuary, the lectern, much of the north chapel and baptistry, a new cover for the font, the choir-stalls and their canopy, figures for the sanctuary niches and an alms box.

There is some suggestion that Plegmund was in Rome around 885, but this is from William of Malmesbury who is notorious for sometimes making mistakes or repeating errors. Once in Rome the typical Anglo-Saxon pilgrim would go straight to the English quarter of the Borgo: the "Schola Saxonum" (later Schola Anglorum), located between the River Tiber and St Peter's (today's Via della Conciliazione - where there is still a church "S. Spirito in Sassia"), and very much financed, backed and protected by many popes due to their special relationship with the English Church. The "Scola" had been built by Leo IV (847-855).

From at least the times of King Aethelwulf of Wessex, father of Alfred, there was a tax levied in England with some regularity, called "Peter’s Pence" or "Romefeoh", sent to Rome as alms for the pope, for St Peter and for the upkeep of the Schola. The records tell of regular journeys to Rome by Saxon almoners carrying the payment. However as Malmesbury is the only source for Plegmund travelling to Rome around 885 (and this part of his works is full of errors) it is possible Plegmund never went on this first trip. William of Malmesbury may share his source with Peter of Ickham possibly the author of the meagre and somewhat confused chronicle entitled 'Chronicon de Regibus Angliæ successive regnantibus a tempore Bruti' (or 'Compilatio de Gestis Britonum et Anglorum') - which also gets things completely confused with Plegmund going to Rome to seek absolution for an excommunicated Edward the Elder from Pope Formosus (see below for more on this). This obvious contradiction (Edward became king in 900 while Formosus died in 896) became the text of the so-called "Plegmund Narrative" often referred to in later church disputes.

An article by Archdeacon Barber from the 1909 Journal of the Chester Archaeological Society contains some speculation on Plegmund (see Link below):

- "He moved about as occasion demanded. If he had a settled abode or cell he would go to places of public resort near at hand, and by his preaching seek to benefit the wayfarers. We can thus imagine St. Plegmund, coming in from the place where he had established himself on an isle of Chester, visiting the City, perhaps taking up his position at one or other of its gates (for it was surrounded with its Roman Walls), and instructing out of his laboriously acquired learning those who were willing to pause and listen to his fervid discourse. The anxious enquirer might return with him to his island home, and after further instruction as a catechumen, might receive the grace of Holy Baptism at the very Well which no bears his name."

This is of course all pure speculation and completely ignores the Viking invasion which was on-going at the time. As for the location of Plegmund's cell, Barber adds an interesting comment:

- "I think, however, I should not omit to notice a passage in Henry IIIrd’s Charter, wherein the King confirms to the Abbot of Shrewsbury (and that Abbey had the Advowson of Plemstall) the grant by Robert the bailiff of Chester "of a hermit’s dwelling in the wood of Sutton"; and as this immediately follows the grants in "Donham" and "Trochford", and is made by an official of this City, Sutton is most probably Guilden Sutton, the parish next adjoining Plemstall on the west. Whether this wood extended beyond the bounds of the township, or whether the boundaries of Plemstall and Sutton have always been the same as they now are, we cannot now determine; but at any rate, here is a coincidence which should not be passed over."

"Donham" may be Dunham-on-the-Hill and "Trachford" Mickle Trafford. However Barber again almost slips into some kind of idyllic view of a stable society when in fact the barbarians were literally at the door. Barber provides no evidence that the "hermitage" of Plegmund was also that which existed some hundreds of years later.

The Early Church in Chester

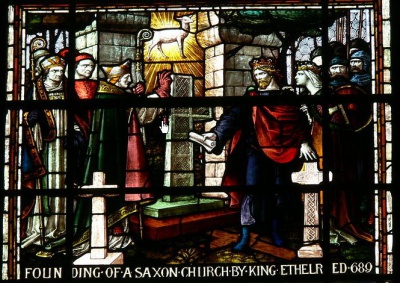

Turning to what else is known of the early church in Chester, the Welsh "Annales Cambriae" record a synod at Chester in 601. Possibly this was related to the mission of Augustine. Around 616 was the Battle of Chester: Æthelfrith of Northumbria against Kings Selyf Sarffgadau of Powys and Cetula (possibly Cadwal Crysban of Rhôs) and possibly also Iago ap Beli - almost certainly at Heronbridge. The Battle of Bangor-is-Coed follows in quick succession and whatever the true events they do seem to have involved a considerable number of monks. The next major "religious" event at Chester may have been foundation of St Johns in Chester which is traditionally ascribed to Æthelred of Mercia in 689.

The deep silence of the Dark Ages then returns to Chester until Ecgbert of Wessex (Alfred's grandfather) captured Chester (briefly) in 828. Ecgbert is a rather obscure character to most people and the sculpture of him at Chester's Town Hall may well puzzle many visitors. His place in history is better understood by considering that the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is in part a propaganda document and attempts to play-up the role of Wessex in history while down-playing the role of Mercia. The Victorian's who built the Town Hall portray him as the first ruler of a united England. Perhaps of equal importance is the fact that when Ecgbert was succeeded by his son Æthelwulf in 839 this was the first father-son succession in Wessex since 641.

Ecgbert was no pagan. In Chester he threw down the statues of Cadwallon. Wiglaf, whom Ecgbert briefly drove out, was also a christian and buried at Repton Abbey in a crypt which still can be seen and which became a noted place for pilgrimage. The monastery church on the Repton site was probably constructed by Æthelbald of Mercia (reign: 716–757) to house the royal mausoleum. As noted above, a similar crypt may have existed on the Amphitheatre site at Chester.

Saint Werburgh or Werberga (d. 699), daughter of Wulfhere, King of Mercia and Saint Ermelida (who was daughter of Eorcenberht, King of Kent) is locally recorded as the first known Abbess of Repton. There are two versions of what followed Werbergh's burial. In the first Werburgh had apparently decided on Hanbury as her final resting place but happened to be at a nunnery at Trentham when she died (Feb 700). The nuns at Trentham refused to give up the body and even instituted security arrangements to prevent its removal. Despite this an expedition from Hanbury succeeded in "miraculously" recovering her remains. According to the second version her brother decided that Werburgh should be moved to the more important site at Hanbury. Existence of the Trentham nunnery is disputed and a connection with Saint Werburgh is also disputed. There are the remains of what is said to be a stepped base for a Saxon stone cross, to be seen today in the churchyard at St. Mary and All Saints at Trentham. But it is not known if this cross base is authentic, an authentic import from elsewhere at the behest of the Sutherland family, or a later antiquarian fabrication. However, there is more evidence of Werburgh's eventual translation to Chester, in 873/4.

There is therefore some suggestion that Chester was already an important religious center at the time of Plegmund, although there is no definite evidence of the existence of a church of canons dedicated to St. Werburgh at Chester before 958. In that year Edgar the Pacific, then "king of the Mercians" (he had just seized it from his brother Edwy), granted to the familia of St. Werburgh seventeen hides of land in Hoseley (Flints.), Cheveley, Huntington, Upton, Aston, and Barrow (next to Plemstall). Barrow and Upton were lost to the familia before 1066. The evidence for a significant religios community at Chester would help the case for Plegmund being there or nearby as it would give him access to a library.

Putting together these scraps of history, it seems that there is a case for Plegmund actually having lived at Plemstall, but this is something of a jigsaw, the reasons being:

- Gervaise of Canterbury has no reason to lie and uses his sources well: he says "in Cestria insula quae dicitur ab incolis Plegemundesham";

- Plemstall was at the time an island surrounded by the tidal swamps of the Gowy;

- Chester was possibly a place of some importance, with an established religious community; because it was the place chosen as a safe haven for the translation of Werburgh;

- Chester's border position would possibly suit one of a missionary temperament;

- Subsequent events at or near Chester involve those whom Plegmund could have influenced - including all of the rulers he had access to;

In the absence of contradictory evidence, it seems reasonably safe to follow Gervaise. Of course there can be no proof (short of digging up the floor) that the present St. Peter stands on the exact spot where Plegmund lived, but it does seem to be at the very northern tip of what was effectively an island.

Political Background

The kings of Wessex between Ecgbert (commemorated at the Town Hall) and Edgar the Pacific (of Edgar's Field fame) show the typical complex succession of the pre-Conquest rulers.

Vikings

During the early life of Plegmund some parts of England were much troubled by Viking raids. The Vikings may even have raided in the Mersey as early as Plegmund's youth as "Helsby" may be a place-name of Viking origin - "Hjalli-by" could be Old Norse for "Village on the ledge" (or "village with a fish-drying rack") and the Gowy has been suggested as both as a Welsh and a Viking border - and there is of course Holme Farm ("Holme" means "island"), which puts a Viking place name right on Plegmund's doorstep. Whether Plegmund had any contact with the local Vikings/Danes is unknown. There are other "Viking" names nearby: another Holme Farm at Ince (also meaning island: as Old Welsh "inis") and a Grinsome Farm, probably from the Norse name Grima/Grimr (one who wears a helmet).

Just why the Vikings started their raids on England when they did has been the subject of some historical debate. It could be that earlier raids during the "Dark Ages" are simply unrecorded, or that population pressure amongst the Vikings eventually led them to expansion and raids. In the year 774, carbon dating shows that something odd happened, possibly a so-called "Carrington Event" brought about by a massive solar flare. This could have damaged ecology and led the Viking society to change in ways which led them to be more expansive. It would also have had led to spectacular auroral displays which might have contributed to societal changes.

During Ceolnoth's archbishopric (833-870), monastic life declined under the pressure of the Viking attacks, and there was a noticeable decline in the quality of the books and other works produced by the scriptoriums. A number of monasteries died out under the pressure of the raids by the invaders, who wintered-over near Canterbury in Kent in 851 and 855. Major Danish invasions took place in 865. The campaign of invasion and conquest against the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms lasted 14 years and resulted in almost the complete conquest of Britain. Although eventually fought to a stalemate by a resurgent Alfred of Wessex, the Danes were not evicted from all of their conquered teritory and retained considerable tracts of land to the east of the country.

Alfred was born in the royal estate of Wantage, historically in Berkshire but now in Oxfordshire, between 847 and 849. He was the youngest of five sons of King Æthelwulf of Wessex by his first wife, Osburh. In 853 Alfred is reported by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle to have journeyed (as a young boy, twice including once with his father) to Rome where he was confirmed by Pope Leo IV, who "anointed him as king". Victorian writers, somewhat obsessed with Alfred, later interpreted this as an anticipatory coronation in preparation for his eventual succession to the throne of Wessex and thence of England. This is unlikely: his succession could not have been foreseen at the time as Alfred had three living elder brothers. In fact, if he had not been so far from the prospect of the throne it is possible he would have been sent on such a dangerous journey. On the way back from Rome Æthelwulf married Judith of Flanders the daughter of the West Frankish king Charles the Bald. Judith was probably born in early 844, which would have made her about 12 when she married the elderly Æthelwulf.

On their return from Rome in 856 Æthelwulf was deposed by his son Æthelbald. With civil war looming the magnates of the realm met in council to hammer out a compromise. Æthelbald would retain the western shires (i.e. historical Wessex), and Æthelwulf would rule in the east. When King Æthelwulf died in 858 Wessex was ruled by three of Alfred's brothers in succession: Æthelbald (died 860), Æthelberht (died 865) and Æthelred (died 871). The causes of death of Alfred's brothers are not all recorded, although "killed in war" is likely. One of the brothers, Æthelbald also married his father's widow Judith (i.e. his own step-mother) something considered scandalous by contemporaries.

Much of the next archbishop Æthelred's time in office (870-888) was also spent dealing with the dislocations caused by the invasion of England by Vikings. However the Archbishop did find time to stir up trouble with the pope. Pope John VIII urged Æthelred and Archbishop Wulfhere of York to reform the dress of the English clergy. The Anglo-Saxon clergy wore the short tunic that was the normal costume of the laypeople of Britain. The Roman custom, however, was to wear long clerical robes or habits, and the Anglo-Saxon custom was opposed by the papacy and other continental clergy. This was probably the least of Alfred's worries given that the Vikings were shifting their strategy from plundering raids to conquest and settlement.

In the winter of 873-4 the Vikings spent the winter at Repton on the middle Trent. Repton is one of the few places where a Viking winter camp has been excavated. Excavations from 1974 to 1988 found a D-shaped earthwork on a bluff, overlooking an arm of the River Trent, and opened a mound containing a mass grave. The mass grave contained the remains of at least 264 individuals. The bones were disarticulated and mostly jumbled together. Forensic study revealed that the individuals ranged in age from their late teens to about forty, four men to every woman. The absence of injury marks on some of the bodies suggest that some members of the party had perhaps died from some kind of contagious disease, which raises the possibility that there was a plague raging in the Viking camp. It was at this time that the relics of Werburgh were translated to Chester. As recorded in the Annales Cestriensis:

- In the same year, when the Danes made their winter quarters at Repton after the flight of Burgred, king of the Mercians, the men of Hanbury, fearing for themselves, fled to Chester as to a place which was very safe from the butchery of the barbarians, taking with them in a litter the body of S Werburgh, which then for the first time was resolved into dust.

It is impossible to say whether Plegmund was living near Chester in 873/4 when Werburgh's remains were brought there, as his time with Alfred can only be dated to some time before 887. However, Alfred only became king in April 871 and his efforts to revive learning did not get underway until the 880's. It is therfore quite possible he was in or near Chester when Werburgh's relics arrived.

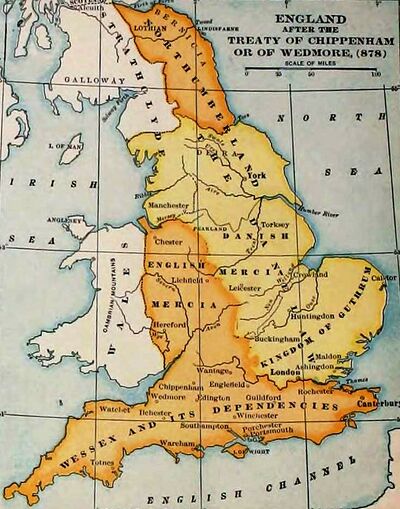

When he first became king in 871 Alfred had almost certainly paid off the Vikings to cease their attacks. After some minor clashes the Danes make a surprise attack in January 878 on Chippenham where Alfred had probably been celebrating Christmas. The king barely escaped and was driven to hide in swamps at Athelney. In the seventh week after Easter (4–10 May 878), around Whitsuntide, Alfred rode to Egbert's Stone east of Selwood where he was met by "all the people of Somerset and of Wiltshire and of that part of Hampshire which is on this side of the sea (that is, west of Southampton Water), and they rejoiced to see him". Alfred won a victory in the ensuing Battle of Edington which may have been fought near Westbury, Wiltshire. He then pursued the Danes to the stronghold at Chippenham and starved them into submission. After the signing of the treaty with Guthrum, Alfred was spared any large-scale conflicts for some time.

The intellectual revival sparked by Alfred entailed the recruitment of "foreign" clerical scholars from Mercia, Wales and abroad to enhance the tenor of the court and of the episcopacy; the establishment of a court school to educate his own children, the sons of his nobles, and intellectually promising boys of lesser birth; an attempt to require literacy in those who held offices of authority; a series of translations into the vernacular of Latin works the king deemed "most necessary for all men to know"; the compilation of a chronicle detailing the rise of Alfred's kingdom and house, with a genealogy that stretched back to Adam, thus giving the West Saxon kings a biblical ancestry. Alfred recruited scholars from the Continent and from elsewhere in Britain to aid in the revival of Christian learning in Wessex and to provide the king personal instruction. Grimbald and John the Saxon came from Francia; Plegmund, Bishop Werferth of Worcester, Æthelstan, and the royal chaplains Werwulf, from Mercia; and Asser, from St David's in southwestern Wales.

Alfred was once cited as the actual translator from Latin of many more of the English-language documents than historians now believe. It is possible that he had some grasp of Latin but it is unclear whether he relied in part or wholly on translation into West-Saxon by his scholars and then dictated his own version. The prose preface added to some of the supposed works claims him as author, but that may have been a convention at the time or a later assumption.

Archbishop

As noted, Plegmund's reputation as a scholar attracted the attention of King Alfred the Great, who was patronizing a literary revival at the Anglo-Saxon court. It is not known what this reputation was based upon but it has been suggested he was a compiler of the Old English Martyrology. This is a collection of over 230 hagiographies, probably compiled in Mercia, or by someone who wrote in the Mercian dialect of the Old English language, in the second half of the 9th century. The sources of the Old English Martyrology include the works of Bede, Aldhelm, Eddius, Adomnán, Gregory the Great, and Isidore of Seville, showing that the scribe had access to a significant library.

Some time before 887, Alfred summoned Plegmund to his court - Asser makes it apparent that Alfred summoned Plegmund to his court before Alfred had learned to read Latin (Asser also states that Alfred could read and write West-Saxon as a boy), and as he learned to read Latin in 887 that establishes a terminus ante quem. At the time, Alfred was having further trouble with his clergy. Around 877, his then archbishop Æthelred wrote to Pope John VIII to complain about King Alfred's conduct towards Canterbury. The exact nature of the dispute is not clear, but the supposed reply from the pope to the archbishop still exists. The pope told the archbishop that Canterbury had papal support and that the pope had written to the king urging the king to respect the rights of the archbishop.

Pleased with his work and holiness, Alfred nominated Plegmund to succeed to the See of Canterbury in 890. Plegmund's election to the Archbishopric of Canterbury is recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (manuscript E):

- "In this year Archbishop Plegmund was elected by God and all the people."

It is curious that Plegmund should have been made Archbishop of Canterbury without evidently having first held an episcopal see or a major abbacy. This is possibly the reason for Asser's perhaps ironic "venerabilem scilicet virum" (an undoubtedly venerable man - scilicet being commonly used to explain an ambiguity), as if there were some contemporary unease about the appointment. Of course, Plegmund was by now very well known to Alfred and was unlikely to write complaining letters to the Pope as his predecessor had done. Also, it should not be forgotten that at the time a bishop was expected to stick with his flock and traditionally could not be translated from one see to another. While this tradition was not always followed it became something of an issue in Rome around the time of Alfred.

Fulk, Archbishop of Reims, praised the election of Plegmund, Flodoard of Reims writes that:

- "(Fulk wrote) to Plegmund, an archbishop across the sea, congratulating him on his good exertions, by which, he had learnt, he was working to cut off and extirpate the incestuous heats of lasciviousness, mentioned above in the letter which he had written to King Alfred, which would seem to have sprung up in that race; instructing him and arming him with the sacred authority of canonical censure, and desiring truly to be surer in his pious labours."

The "incest" may well refer back to Judith's marriage both to Alfred's father and then to his brother. Plegmund's connection with Fulk would come back to haunt Plegmund in a curious way. Upon the deposition of Emperor Charles the Fat in 887, Fulk tried to install his kinsman Guy II, Duke of Spoleto, on the throne and even crowned him at Langres (888), but to no avail. A later Guy IV of Spoleto would stir up trouble in Rome which eventually meant that Plegmund would briefly lose his position as Archbishop.

There is further correspondence at the time which points to Plegmund already having a reputation as more than a simple teacher. This is discussed by Matthews cited below. However, there is a mysterious gap in time between the death of the previous Archbishop of Canterbury, Ethelred (died June 888), and the consecration of Plegmund; this may have been because the see had been offered to Grimbald, a Flemish monk and scholar, who refused it. Although of dubious historical accuracy, the life of Grimbald was recorded in several volumes, of which the main source is referred to as the Vita Prima of St. Grimbaldi. According to the Vita Prima, King Alfred met Grimbald before his reign, and after his coronation invited Grimbald to England around 892.

Plegmund was granted his pallium by Pope Formosus (861-896), the same pontiff who was famously tried posthumously in the famous Cadaver Synod. William of Malmesbury appears to suggest that Formosus had written to Plegmund proposing him as archbishop. On being elected Archbishop, Plegmund apparently travelled to Rome, where he received the pallium from Pope Formosus:

- Hic Romam profectus a Formoso papa sacratus est palliumque suscepit et metropolitani plenitudinem potestatis (Gervase of Canterbury)

A trip to Rome was a risk, but Alfred had been to Rome and so Plegmund could perhaps hardly refuse. The last archbishop of Canterbury to visit Rome had been Wulfred in 812 and the normal practice was to send the pallium by messenger. Wulfred only went because he was involved in a dispute. For this reason some historians have questioned whether this first visit to Rome was a fabrication in later chronicles. Given that it was so rare an event it is surprising that the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle does not mention it.

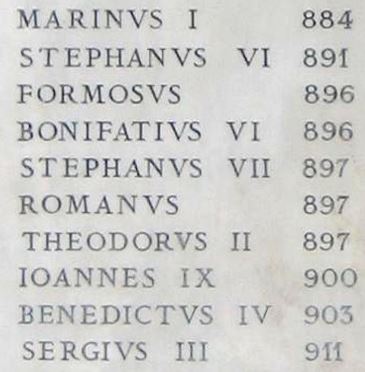

Formosus had a colourful career. John VIII accused Formosus of corrupting the Bulgarians and undermining the authority of the Holy See because the Bulgarians did not want any Bishop except Formosus. In 876 Formosus was excommunicated from the Church. However, John VIII was killed in 882: said to be the first pope in history to suffer such a fate (if we ignore a long list of supposed martyrs). First the assassin poisoned him and then, impatient at the slow working poison, the assassin bashed his head in with a hammer or club. Formosus was then pardoned of all "crimes". Then there was Pope Marinus I, Pope Adrian III, and Pope Stephen V. In 891, Formosus was himself elected Pope, a position he held until his death in 896 of a stroke (officially ‘struck by paralysis’ which could also mean a possible poisoning). While in office, Formosus made a lot of enemies in the upper echelons of power in Constantinople, the Holy Roman Empire, Italy, and within the Church itself. He also was persistently bothered by the relentlessly encroaching Saracens. As Formosus became Pope in 891, this suggests that Plegmund (if he did make the journey) did not set out for Rome immediately upon his election in 890.

However it occurred, Plegmund had his Pallium and was established at Archbishop with the official sanction of the Pope and even an encouraging letter from Fulk - what could possibly go wrong?

The Pope who came back from the dead

The Cadaver Synod (also called the Cadaver Trial; Latin: Synodus Horrenda) was held in the Basilica of St. John Lateran in Rome during January 897. The trial was conducted by Pope Stephen VI (896-97), the successor to Formosus' own direct successor, Pope Boniface VI (pope in 896 - for 15 days). Stephen had Formosus' rotting corpse exhumed and brought before an unwilling papal court for judgment. He accused Formosus of continuing to enact the functions of a Bishop when under interdiction and claiming the Pontificate when not yet a Cardinal and inelegible to do so. There was an earthquake during the trial:

- "For the stones themselves, execrating such a monstrosity, then cried out with their own voice by knocking against each other, that they would more willingly suffer spontaneous ruin, than that the Roman Church should remain depressed by so great a scandal."

At the end of the trial, Formosus was pronounced guilty and his papacy retroactively declared null and void. Stephen VI had been made bishop of Anagni by Pope Formosus, possibly against his will - and does not seem to have considered the effect of his verdict against Formosus on the validity of his own ordination. Pressure from the Spoleto contingent and Stephen's fury with his predecessor probably also precipitated this extraordinary event. It is also possible that Stephen was simply completely insane (officially: "induced by an evil passion").

With the corpse propped up on a throne, a deacon was appointed to answer for the deceased pontiff (the Deacon spent much of the trial crouched in fear behind the throne) and did not help his client by providing answers on his behalf like: "Because I was evil". During the trial, Formosus's corpse was condemned for performing the functions of a bishop when he had been deposed and for receiving the pontificate (i.e. becoming bishop of Rome) while he was already the bishop of Porto (the Roman suburb): these were among other revived charges that had been levelled against him in the strife during the pontificate of John VIII. The corpse was found guilty, stripped of its sacred vestments, deprived of three fingers of its right hand (the blessing fingers of the benediction), clad in the garb of a layman, and quickly buried; it was then re-exhumed and thrown in the Tiber to complete the damnatio memoriae. The scandal ended in Stephen's imprisonment and his death by strangling that summer. Liutprand of Cremona adds a postcript that:

- "When he [Formosus] was afterwards found by fishermen and carried to the Church of the blessed Prince of the Apostles, certain images of the saints, with veneration, saluted him, placed in his coffin; for this I have very often heard from most religious men of the city of Rome."

Formosus' no doubt irritating refusal to stay in the river and his subsequent working of miracles inflamed feelings in Rome and were retroactively considered a factor in Stephen's downfall. Barber's Journal article makes no mention of the above strange circumstances. Barber simply writes:

- "Plegmund paid a second visit to Rome. There is some doubt as to the date and the reason of this. It has been assigned to the close of 908; and Dr. Hook says it was necessitated by Pope Stephen having annulled the acts and ordinations of Formosus, owing to some irregularities and indiscretions on his part. If Dr. Hook's view is correct, as also his statement that Plegmund submitted to the questionable ceremony of re-consecration, the assigned date cannot be correct, for in 905, at a Synod held at Ravenna, the ordinations of Formosus, on which doubts had been cast, were confirmed."

By the year 900, the structure of the medieval English Church had not been substantially modified for almost 300 years since the days of the missionaries. Plegmund sought to reform the structure of the Church to make administration more efficient and increase the authority of his own See of Canterbury.

Off to Rome (again?)

To do this, Plegmund had to gain the approval of Pope Sergius III (904-911), who in 904 had confirmed the annullment (from 897) of all of the acts of Pope Formosus. This was a little complicated, in December 897, Pope Theodore II had (during his 20 days as pope) convened a synod that annulled the Cadaver Synod, rehabilitated Formosus, and ordered that his body, which had actually been recovered from the Tiber, be reburied in Saint Peter's Basilica in pontifical vestments (apparently he still rests there). In 898 John IX became pope, after Sergius, an old enemy of Formosus, had for a few months established himself by violence in the papal chair. John, who had been ordained by Formosus, completed the work which Theodore had begun. First at a synod in Rome, and then at a great council in Ravenna, he condemned the gross wickedness of the mock trial. All the acts of Formosus were now reinstated: this would have included the ordination of John IX himself. A few popes later Sergius returned as established pontiff and overturned things again. For centuries it was believed that Sergius then had the much-abused corpse of Formosus exhumed once more, tried, found guilty again, and beheaded, thus in effect conducting a second Cadaver Synod. However, the source for this was Liutprand of Cremona, who mistakenly placed the cadaver synod in the pontificate of Sergius III, instead of Stephen VI.

This was problematic, for the re-nullification of the acts of Formosus also nullified the appointment of Plegmund to his see, which necessitated Plegmund travelling to Rome in 908 so that he could be regranted his pallium by Sergius III. Plegmund might have considered this an even more hazardous trip than is first - because Sergius III had reputedly (according to Auxilius of Naples) ordered the murder of his two immediate predecessors, Leo V (903-4) and Antipope Christopher (also 903-4), and allegedly fathered an illegitimate son who later became pope as John XI (898-900). Sergius' pontificate has been variously described as "dismal and disgraceful", and "efficient and ruthless". The period following the installation of Sergius is known as the "Saeculum obscurum". This "Dark Age" lasted sixty years until the death of Pope John XII in 964. During this period, the popes were influenced strongly by a powerful and allegedly corrupt aristocratic family, the Theophylacti, and their relatives. It was not the safest time to travel to Rome.

Whether he went once or twice, Plegmund was the first archbishop of Canterbury to visit Rome for nearly a century, and evidently made a good impression as he supposedly returned with the relics of the somewhat obscure Saint Blaise, having however paid a vast sum for them. A trip to Rome was not a minor matter as it was dangerous and had been unattempted by any of Plegmund's predecessors since Wulfred (died 832 - not to be confused with Wilfred, see: Amphitheatre) in 814-15. Not only had Plegmund to cross the continent he also had to engage with a possibly murderous Papal court in a nest of potentially lethal intrigue. As noted above, some chronicles support the view that Plegmund visited Rome twice. Marinus, a former pope (882-884), had granted exemption from all taxes and tolls to the Saxon School at Rome, and had sent sundry presents to the King of England, amongst them being a piece of the supposed "True Wood of the Cross". In return for these favours it is said that:

- "Plegmund, upon his first return from Rome, busied himself in collecting money from all well-disposed persons to the Papal See, to which the King himself apparently added from the Royal Treasury; this he sent to the Pope."

One problem with this is that the phrase all well-disposed persons to the Papal See seems to be taken from a much later document of Pius IX. Curiously, Pius was pope at the demise of the Papal States (when Laurens made his painting of the Cadaver Synod) and the aforementioned quote might be read with that context in mind.

Reform of the Church

Under Plegmund's leadership, the quality of the Latin used by his scribes improved, surpassing the poor quality used by the scribes of the previous two archbishops, Ceolnoth and Æthelred. This improvment also casts doubt on the theory that Plegmond was a mere hermit: it called for skill in practical education and administrative capacity, neither of which are likely attainments for a man who had spent many years as an isolated hermit on an island in a swamp at Plemstall.

When Alfred died in 899, Plegmund presided at the coronation of his son, Edward the Elder, as king. This was despite Plegmund's on/off position as archbishop being on shaky ground given it had been granted by Formosus. It is possible that when Gervaise records the coronation he actually refers to the uncertain status of the Archbishop with an inserted "it is said".

Edward had good grounds for wanting his coronation to be as official as possible. When Alfred had become king there were already existing sons of his older brother. However, Æthelwold and his brother Æthelhelm were still infants when their father the king died in the midst of a conflict with the Danes, and therefore Alfred became king. Alfred and his brother seem to have agreed that this would happen, but may not have agreed what would happen once both were dead.

On Alfred's death Æthelwold disputed the throne with Edward the Elder. As senior ætheling (prince of the royal dynasty eligible for kingship), Æthelwold had a strong claim to the throne. He attempted to raise an army to support his claim, but was unable to get sufficient support to meet Edward in battle and fled to Viking-controlled Northumbria, where he was accepted as king. In 901 or 902 he sailed with a fleet to Essex, where he was also accepted as king. It is entirely possible that one bit of "propaganda" at the time was that, given that Plegmund was not a valid Archbishop, Edward is therefore not a valid king.

Things now get even more compicated for Edward and his sister Æthelflæd. Ingimund was a Viking who had been expelled from Ireland on 902 and had attempted to settle in north Wales where he came into immediate conflict with the Welsh. Ingimund's subsequent move to the Wirral is only based on evidence from the Fragmentary Annals of Ireland:

- "Now the Norwegians left Ireland, as we said, and their leader was Ingimund, and they went then to the island of Britain. The son of Cadell son of Rhodri was king of the Britons at that time. The Britons assembled against them, and gave them hard and strong battle, and they were driven by force out of British territory. After that Ingimund with his troops came to Aethelflaed, Queen of the Saxons; for her husband, Aethelred, was sick at that time. (Let no one reproach me, though I have related the death of Aethelred above, because this was prior to Aethelred's death and it was of this very sickness that Aethelred died, but I did not wish to leave unwritten what the Norwegians did after leaving Ireland.) Now Ingimund was asking the Queen for lands in which he would settle, and on which he would build barns and dwellings, for he was tired of war at that time. Aethelflaed gave him lands near Chester, and he stayed there for a time."

One connection that historians seem to have missed is that Ingamund the Dublin Viking arrives in the Wirral at the same time that Æthelwold (Edwards rival for the throne) is in Essex with his Viking support from Northumbia. Edward is stuck in the middle. It seems to have been Æthelflæd who came up with the solution - alow the Irish/Norwegian Vikings in the Wirral to settle and then defeat Æthelwold and his Northumbrian/Danish Vikings in Essex. This is effectively what happened and Plegmund's trip to Rome thereafter could in part have been to ensure that Edward's coronation was confirmed as valid.

In addition to his religious duties, Plegmund was involved in matters of state and he attended the formal councils held by Edward the Elder in 901, 903, 904 and 909. Following his return from Rome in 908, between 909 and 918 Plegmund created new sees within the existing Diocese of Winchester in Crediton, Ramsbury, Sherborne and Wells. This meant that each future shire of Wessex had its own "metropolitan" bishop; of Crediton for Devon and Cornwall, of Ramsbury for Wiltshire, of Sherborne for Dorset and of Wells for Somerset, as well as the somewhat reduced diocese of Winchester for Hampshire. As discussed in further detail below, Plegmund's reform of the church divided and hence weakened the old West Saxon sees of of Winchester and Sherborne and in this he may have had a hidden agenda to stack the episcopate with his own, reform-minded bishops.

Plegmund dedicated the "lofty tower" of the New Minster at Winchester in 909. Alfred the Great had intended to build the monastery, but only got around to buying the land. His son, Edward the Elder, finished the project according to Alfred's wishes, with the help of Saint Grimbald who became its first abbot. It stood so close to the Old Minster that the voices of the two choirs merged with chaotic results. The body of King Alfred was transferred to the New Minster, Grimbald's body eventually joined him and it was also given the body of the Breton Saint Judoc (Saint Josse), making it an important pilgrimage centre. Queen Emma added the head of Saint Valentine in 1041.

Death

After "a life full of apostolic labors", Plegmund died at an advanced age on 2 August 914 (according to some) or 2 August 923 (which is more likely) - when according to Gervase of Canterbury he had been in office for 34 years. The correct text of the Anglo Saxon Chronicle reads:

- 923. "This year went King Edward with an army, late in the harvest, to Thelwall; and ordered the borough to be repaired, and inhabited, and manned. And he ordered another army also from the population of Mercia, the while he sat there to go to Manchester in Northumbria, to repair and to man it. This year died Archbishop Plegmund; and King Reynold won York".

The wrong (914) date of Plegmund's death is still given in many sources. After his death Plegmund was venerated as a saint, with a feast day variously attreibuted to the 2nd or 14th August. However, there is little evidence of his cult before the 13th century, and he is not the "patron" saint of anything in particular. He was originally buried in the Church of St. John at Canterbury, where his remains rested until the fire of 1067.

On the rebuilding of the Cathedral by Lanfranc, the remains were probably placed in a vault in the north transept; but after the attempts to steal the bones of Archbishop Breogwine in 1121, the monks removed them to near the altar of St. Gregory in the southernmost apse of the south-east transept, where they were placed behind the altar. The Chronicle of John Stone, who was a monk of Christ Church in the time of Prior Molash (1427-1437), tells us that there was an image of Archbishop Plegmund, together with one of St. Odo and twelve others, placed in the choir of the Cathedral in his day. These were probably all removed under the Injunctions of Edward VI in 1547. St Plegmund’s Roman Catholic Church was built in Tattenhall in the 1970's, but closed during the Autumn of 2012 and the building was demolished in the Autumn of 2014 to make way for a housing development.

Legacy

Part of the legacy of Plegmund was the so-called Plegmund Narrative which provided a rich source for those wishing to concoct papal decrees, especially just after the Norman Conquest when Lanfranc was installed as Archbishop of Canterbury. As is said of it:

- * "It was perhaps the Winchester copy which played a curious part in the great struggle for precedence between Canterbury and York. When Lanfranc came to Canterbury, in 1070, he found his metropolitan church in ruins; and the most valuable records of his see were said to have perished in the flames. When the controversy with York was at its height, two years later, some of his monks (if not the archbishop himself) thought it necessary to reconstruct their ancient privilegia, as weapons for a contest which doubtless was really decided on grounds of policy even more than of tradition. Among the ten papal privileges which were ultimately produced in evidence was a letter of Pope Formosus. It is exceedingly improbable that this pope's name would ever have been invoked but for the existence of the Plegmund narrative, which offered an irresistible temptation to the ingenious constructor of papal documents. As it is, the ninth of the privileges takes the form of a letter in which Pope Formosus begins by retracting his former threats — ' mucronem devotationis retrahentes . . . benedictionem vobis mittimus ' — and proceeds, after various injunctions as to regularity in the appointment of bishops, to confirm the supremacy of Canterbury over the whole of the English Church. The Plegmund narrative tells us that the pope, when he wrote his letter, was i motus cum magna iracundia et devotatione and threatened to send maledictionem instead of benedictionem ; so we may be sure that our document was in the forger's hands. Indeed its preservation in the Canterbury Registers is solely due to the fact that the monks thought that it would lend verisimilitude to what followed, if they included this ancient document in the record of their privilegia, though it had no bearing at all on the question in dispute. Accordingly it stands just before the ninth privilege under the title Memorabile factum. It occupies the same place, and bears the same title, in Eadmer's second edition of his Historia Novorum (Rolls Series, pp. 261-76). William of Malmesbury gives the privilegia in his Gesta Pontificum (p. 59), including the letter of Formosus, but not the Plegmund narrative. This he reserves for his Chronicle of the kings of England, where he introduces it with the words 'iocundum puto memoratu*. Thus the memorable fiction found its way into the orthodox history of the English Church."

Lanfranc was nominated to the English Primacy as Archbishop of Canterbury as soon as Stigand had been canonically deposed on 15 August 1070. He was speedily consecrated on 29 August 1070. The new archbishop at once began a policy of reorganisation and reform. His first difficulties were with Thomas of Bayeux, Archbishop-elect of York, (a former pupil of Lanfranc) who asserted that his see was independent of Canterbury and claimed jurisdiction over the greater part of the English Midlands. This was the beginning of a long-running dispute between the sees of Canterbury and York. In 1127, the dispute over the primacy was settled mainly in York's favour, for they did not have to submit to Canterbury. However the dispute would flare up again and again: no firm settlement was made until the 14th century.

The text of the so-called letter of Pope Formosus to the Bishops of England is suitably vague, calls the bishops "dogs" and threatens excommunication:

- "..having heard that the wicked rite of the pagans had once agam sprouted in your lands, and that you had kept silent like dogs who have not the strength to bark, we had decided to smite you with the sword of separation from the body of the Church of God. But since, as our beloved Plegmund has made known to us, you have at last awoken and begun to renew the seeds of the Word of God(long since reverently cast upon the land of the English), we draw back the blade of our curse, and send you the blessmg of omnipotent God and of the blessed Peter, foremost of the apostles, praying that you persevere in an enterprise so well begun..."

Historians are still divided as to what extent the letter is a fake. The myth of the "Plegmund narrative" was taken as truth by many historians well into the 20th Cent, and still persists in some modern accounts of Plegmund's life. Much ink has been spilt on the question of which accounts are true and which may be forgeries.

Plegmunds's Life: A summary

Plegmunds early life remains a mystery and there are problems reconciling the story of his long residence at Plemstall with his rise to become Archbishop. More solid evidence supports his role in educating and advising Alfred and getting caught-up in the strife surrounding Formosus. He may have only been to Rome once, and that would have been to confirm the validity of his position and hence of Edward's coronation. His reform of the church is known to have taken place, but even that would be misreported, as described below.

Works

With the exception of Asser, it is difficult to say who actually wrote what, or rather translated what, among the group of scholars which Alfred collected. Instead it is better to focus on the structural establishment of literary norms in which Plegmund was involved.

One misconception which can be disposed of quickly is that Plegmund was the author of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. It does appear that it was propaganda, produced by Alfred's court and written with the intent of glorifying Alfred and creating loyalty. This is not universally accepted, but the origins of the manuscripts clearly colour both the description of interactions between Wessex and other kingdoms, and the descriptions of the Vikings' depredations. An example can be seen in the entry for 829, which describes Ecgbert's invasion of Northumbria. According to the Chronicle, after Egbert conquered Mercia and Essex, he became a "bretwalda", implying overlordship of all of England. At the time when the sculptures at Chester Town Hall were being created Ecgbert's role as the first ruler of all England was generally accepted and this is what is depicted. In truth, Mercia soon regained its independence under Wiglaf — the Chronicle merely says that Wiglaf "obtained the kingdom of Mercia again", but the most likely explanation is that this was the result of a Mercian rebellion against Wessex rule. However, when the Town Hall in Chester was being built there was a desire to put Chester forward as the place where England came into existence - hence the relief showing Ecgbert accepting the crowns of the various kingdoms which then made up "England". The wording on the relief is sufficiently vague as to imply that the probably fictional event took place at Chester and does not provide any indication of the fact that Ecgbert was from Wessex.

With all his reform of the church it is at first surprising that Plegmund is hardly known. Plegmund's successors were all bishops from the West Saxon establishment and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle shows a definite bias towards the Wessex view of history rather than the Mercians. Mercian rulers such as Ceolwulf II are seen as "foolish", and Æthelflæd was almost written-out of history. Asser does an excellent job of shifting the focus of the transformation of scholarship to Alfred and Edward the Elder would quickly quash any hope of Mercian independence after the death of his sister.

Pastoral Care

The Book of Pastoral Rule (Latin: Liber Regulae Pastoralis, Regula Pastoralis or Cura Pastoralis — sometimes translated into English Pastoral Care) is a treatise on the responsibilities of the clergy written by Pope Gregory the Great around the year 590, shortly after his papal inauguration. Pope Gregory the Great (r. 590–604) was revered in Anglo-Saxon England because he had sent Augustine to convert the English to Christianity. The translation made at Alfred's court of the book is the oldest surviving book written in the English language. The preface, said to be written by Alfred himself, claims that it was also Alfred himself who made the translation. Historians agree that Alfred had a part in the production, but consier it unlikely that he would have done the actual translation. In the preface Alfred describes how the standard of Latin learning had declined so much following many decades of Viking attacks that, whereas once the land had been a magnet for foreign scholars, now learning had to be acquired from beyond its borders. Alfreds solution is not to start by educating the English in Latin (which Plegmund had taught him some of) but by translating religious works from Latin into English and using these for education. The better students could then go on to learn Latin as required.

Despite the clear statements in the preface to the Pastoral Care, historians record different collaborators. In general Plegmund worked with three other scholars, Wærferth, Bishop of Worcester, Æthelstan (priest and chaplain, probably bishop of Ramsbury from c. 909) and Wærwulf (priest and chaplain, a friend and associate of Werferth according to charters) in working on translating the treatise into Old English, one of the most important translations of Alfred's reign. The core of the community of scholars appears to have been:

- Plegmund: very much an outsider, having had no former, formal religious position;

- Bishop Asser: a Welsh monk from St David's, Dyfed, who became Bishop of Sherborne (Salisbury) in the 890s. About 885 he was asked by Alfred the Great to leave St David's and join the circle of learned men whom Alfred was recruiting for his court. After spending a year at Caerwent because of illness, Asser accepted;

- Mass-priest Grimbald: a Benedictine monk at the Abbey of Saint Bertin near Saint-Omer, France, who was probably sent by Fulk;

- Mass-priest John the Old Saxon: (active c. 885–904), also known as John of Saxony or Scotus, was a scholar and abbot of Athelney, probably born in Old Saxony (hence his name - he wasn't aged). He was invited to England by King Alfred and contributed to Alfred's revival of English learning. In his life of Alfred, the Asser reports that John "was a man of most acute intelligence, immensely learned in all fields of literary endeavour, and extremely ingenious in many other forms of expression";

Copies of the work were sent to at least:

- Plegmund;

- Werferth: the English bishop of Worcester;

- Heahstan: a Bishop of London;

- Wulfsige: a ninth-century Bishop of Sherborne;

- Swithulf: Bishop of Rochester;

Plegmund's own copy of the work is that preserved in the British Museum. It is a fascinating read (there is a modern English translation in the links below), and can be compared to Niccolò Machiavelli's "The Prince" as an instruction guide for the upper-classes and the clergy, but with a completely different approach. Given that Plegmund had almost certainly studied the work prior to moving to Alfred's court, it can be speculated that some of the interpretations which found their way into Alfred's version may have been formulated in what is now Plemstall.

Since Wulfsige, Heahstan and Swithulf (and possibly other bishops) are mentioned only as recipients of the Pastoral Care, they are probably only marginally relevant to the immediate Alfredian network. What is conspicuous is that not one of the actors, except Alfred himself, is a West Saxon. Indeed the other actors spoke Welsh, Mercian and continental Germanic varieties yet worked to produce works in West Saxon. They come from a variety of places, where education and scholarship were in better state than in Wessex. As Asser testifies, Werferth, Plegmund, Bishop Æthelstan and Wærwulf are from Mercia, Asser himself is from Wales, Grimbald and John come from Gaul (Galliam), although their home places are identified as Flanders and Saxony, respectively. The origins of the royal chancery are traced to Winchester and the court of King Alfred. In the Alfredian period Winchester charters display strong influence of the Mercian diplomatic tradition, but towards the 930s (after the death of Plegmund, under King Edward the Elder (899 - 924) and King Æthelstan (924 - 39) new norms develop that reflect both their Mercian origins and West Saxon adaptation. With the Mercian influence being strong in Latin charter material, it seems reasonable to assume that the four Mercian advisers of King Alfred (Plegmund, Werferth, Æthelstan and Wærwulf) were also somehow involved in the organisation and work of the proto-chancery.

The same school which produced the translation of Pastoral Care also seems to have produced the Old English Boethius. The translation is attributed in one manuscript to King Alfred, and this was long accepted, but the attribution is now considered doubtful. Boethius was a Roman senator, consul, magister officiorum, and philosopher of the early 6th century. The translation is thought to have originated between about 890 and the mid-tenth century, possibly but not necessarily in a court context, and to be by an anonymous translator. Sometime after the composition of the prose translation, someone adapted the prose translations of Boethius's metres into Old English alliterative verse. It is not known whether Plegmund had a hand in the translation, but it illustrates the wide scope of the ancient texts which came out of the Alfredian translation program. A link to the text is provided below.

One curious fact which may attest to the strength of the Mercian influence is the adoption of the term "Angelcynn", literally Angle-kin, the race of the Angles, as one of the buzz words of King Alfred's court. The Mercians were predominently Angles, while the people of Wessex were Saxons. On the whole it appears that Angelcynn as a lexical norm for the English people was enforced among the Alfredian network, in particular among the coalition formed around the Mercian cluster. Thus, despite the West Saxon dialect becoming the standard written variety, the name of the people became the English.

Ordo

The following archbishop was Athelm who was the first Bishop of Wells, and later Archbishop of Canterbury. His translation, or moving from one bishopric to another, was a precedent for later translations of ecclesiastics, because prior to this time period such movements were considered illegal. While archbishop, Athelm crowned King Æthelstan in 924, and perhaps wrote the coronation service for the event. An alternative view is that Plegmund (who lived until 923) had already composed or organised the new Ordo (order of service) in which for the first time the king wore a crown instead of a helmet, however Plegmund may have had no reason to suspect that Edward the Elder would die so soon. However there is a possibly interesting connection between the so-called "Leofric Missal" and Plegmund. The core of the book, which modern scholars have designated ‘Leofric A’, was produced in northern France at the end of the ninth century. This book was then imported to England and taken to Canterbury where many additions were made, including a set of prayers and blessings to be used at the coronation of a king. A number of insular saints are also invoked — Alban, Boniface, Patrick, Cuthbert, Guthlac, Brigid, and perhaps Paulinus of York. These details suggest that the book was devised for an English patron, not least because Guthlac is unknown in Continental litanies until after the Conquest. Perhaps the mention of the Mercian island-dwelling hermit Guthlac points a direct finger at Plegmund's involvement.

Plegmund's Well

Plegmund's memory in Chester has been kept alive in part due to his well. The way in which the memory of the well has been kept alive provides an interesting epilog (for the present) to the history of Plegmund.

The well is first recorded in a mention from Ormerod of a quitclaim dating from 1301 as "St Pleymond's Well". The monument includes a holy well dedicated to St Plegmund, an Anglo-Saxon saint, Archbishop of Canterbury AD 890-923. Many historians agree that the site of St Peter's church at Plemstall was possibly a hermitage occupied by the saint in the late 9th century and the well is associated with this foundation. Gervaise does not mention the well, but it's name and location in Plemstall fit well. In medieval times the well was known as a christening well, a name that it retains locally to the present. Plemstall is unusual in Cheshire in that although it is the name of a parish, it is not also a township. Today the area known as Plemstall contains only the former vicarage, a former level-crossing keeper's cottage (both now private residences), St Peter's Church and a farm. Notably, "Holme Farm" derives it's name from the Middle English word for a small island or islet.

A Catholic pilgrimage to the well took place in 1938: this was probably an initiative of Canon Frank Murphy, who was a curate at St Werburgh’s in Grosvenor Park Road Chester during the 1930s. He returned as parish priest from 1959 to 1982, and then organised an annual pilgrimage from St Werburgh’s to the well. There are plenty of pleasant footpaths around the area today.

The well is a stone-lined pit with two steps down into the sink on the south side. Beneath this is a circular rough stone well 0.4m in diameter descending for 0.5m to the soakaway. Half of this well is obscured under the stonework lining the northern side of the pit. The pit is of dressed stone and is 1.3m wide east to west, 1.5m wide north to south and 0.4m deep. Flanking the pit on the east and west sides are two large dressed stone slabs, 1.5m by 1m and decorated with a rebate on two sides. These formed a cover for the well and are now left permanently aside.

The well pit was restored in 1907 and, shortly thereafter, an inscribed curb placed around the top, which has since disappeared. The stone was paid for by Mr Osborne Aldis (the son of Charles James Berridge Aldis) and dedicated by the venerable E. Barber, Archdeacon of Chester. The inscription apparently read:

- Hie fons Plegmundi functus baptismatis usu Regnante Alfredo, tunc hodieque solet. (Freely translated as: "Here as in days when Alfred erst was king, baptismal water flows from Plegmund's spring").

More can be found on this in the Chester Courant and Advertiser for North Wales (5th August 1908), where Aldis himself writes of a unexpected visit he made with "Rev ---- Dempster" someone he met by chance on the way to the fifth Lambeth Synod (a Hubert Alfred Dempster was in fact a delegate):

- "Should it be for the time forgotten, I trust soon to remind you. To conclude, Mr. Dogg, the well-known statuary mason of Chester, has drafted for me a simple memorial, which is already submitted for the approval of the landowner - the Earl of Shrewsbury - requesting the necessary permission for erection, and it is to be hoped that its inauguration may take place at no distant date."

Fragments of dressed stone lying on the north side of the well may, however, be part of the Aldis curb. This curb was made by stonemasons Henry Clegg & sons (est. 1878). They also constructed Hoole’s War Memorial and had a yard Station Road under the shadow of Hoole Bridge and offices at 11 Brook Street. As reported in the local newspapers at the time:

- "To Mr. Osborne Aidis, M.A., of Chester, is due the credit for rescuing from perhaps oblivion this more than interesting spot. Though the well was known to many antiquarians and others, but previously it was always in danger of being damaged or suffering from the ravage of the weather etc. Now, by the generosity and foresight of Mr. Aldis, it has been enclosed by a plain but appropriate protecting wall and brought prominently before the public eye."

The steel railings and the surface of the road 0.5m to the south of the monument, where they fall within the wells protective margin, are excluded from the scheduling, although the ground beneath them is included. Somewhere there is a small remembrance to Aldis, for the papers back in 1908 recorded:

- "On the right return of the stone are the letters D D (Dono Donavit), with the name of Aldis Osborne M.A. On the left return appears the year A.D. 1908."

Modern signage at the well explains that the arch errected over it was unveiled on 16th June 2002. In recent years Plegmund's Well has been the subject of "Well Dressing" - a tradition practised in some parts of rural England in which wells, springs and other water sources are decorated with designs created from flower petals. It has been speculated that it began as a pagan custom of offering thanks to gods for a reliable water supply; other suggested explanations include villagers celebrating the purity of their water supply after surviving the Black Death in 1348, or alternatively celebrating their water's constancy during a prolonged drought in 1615. Until recently the custom of well dressing was restricted largely to Derbyshire and areas nearby.

The well is similar in construction to St Anne's Well at Rainhill, and another St Anne's Well may have given its name to "Synagogue Well" at Frodsham. There may have once been a pilgramage route between these wells, or possibly, they were associated with childbirth or baptism.

Plegmund, Edward, Æthelflæd and Æþelstān

Some further evidence for Plegmund having a particular connection with Chester can posibly be determined by considering how he might have influenced local events. This is an unorthodox approach, but with a shortage of further documentation one of the available. Thus, having possibly placed Plegmund's formative years in a time and space context near Chester. is interesting to speculate whether the Mercian Plegmund was involved with Æthelflæd's refortification of Chester and her promotion of the cult of Werburgh. Plegmund was the last survivor of the "core group of scholars" who were assembled by Alfred and lived on longer than Æthelflæd and almost as long as Edward the Elder, both of whom took a major part in the defence of the north of Mercia and the reconquest of the east of Mercia. He also may have been an influence on the young Æþelstān who was to succeed Edgar and fight a major battle just north of Chester. Plegmund's past association with Chester therfore leads to an enquiry as to his invovements with future events in the area.

Alfred

Alfred possibly visited Chester. In around 894 there was an invasion by the Danes which involved a forced march on Chester and possibly the occupation of the Amphitheatre. The event appears to have involved the notable Viking chieftain Hastein. The following account appears in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle:

- Þa hie on Eastseaxe comon to hiora geweorce. 7 to hiora scipum. þa gegaderade sio laf eft of Eastenglum, 7 of Norðhymbrum micelne here onforan winter 7 befæston hira wif, 7 hira scipu, 7 hira feoh on Eastenglum, 7 foron anstreces dæges 7 nihtes, þæt hie gedydon on anre westre ceastre on Wirhealum, seo is Legaceaster gehaten; Þa ne mehte seo fird hie na hindan offaran, ær hie wæron inne on þæm geweorce; Besæton þeah þæt geweorc utan sume twegen dagas, 7 genamon ceapes eall þæt þær buton wæs, 7 þa men ofslogon þe hie foran forridan mehton butan geweorce, 7 þæt corn eall forbærndon, 7 mid hira horsum fretton on ælcre efenehðe. 7 þæt wæs ymb twelf monað þæs þe hie ær hider ofer sæ comon. (As soon as they came into Essex to their fortress, and to their ships, then gathered the remnant again in East-Anglia and from the Northumbrians a great force before winter, and having committed their wives and their ships and their booty to the East-Angles, they marched on the stretch by day and night, till they arrived at a western city in Wirral that is called Chester. There the army could not overtake them ere they arrived within the ramparts: they besieged the ramparts though, without, some two days, took all the cattle that was thereabout, slew the men whom they could overtake outside the ramparts, and all the corn they either burned or consumed with their horses every evening. That was about a twelvemonth since they first came hither over sea.)

In the autumn the besieged army left Chester, marched down to the south of Wales and devastated the Welsh kingdoms of Brycheiniog, Gwent and Glywysing, until the summer of 894. They return via Northumbria, the Danish held midlands of the Five Burghs, and East Anglia to return to the fort at Mersea Island. In the autumn of 894, the army towed their ships up the Thames to a new fort on the River Lea. In the summer of 895 Alfred arrived with the West Saxon army, and obstructed the course of the Lea with a fort either side of the river. The Danes abandoned their camp, returned their women to East Anglia and made another great march across the Midlands to a site on the Severn (where Bridgnorth now stands), followed all the way by hostile forces. There they stayed until the spring of 896 when the army finally dispersed into East Anglia, Northumbria and according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, those that were penniless found themselves ships and went south across the sea to the Seine. Curiously, Asser's "The Life of King Alfred" breaks off suddenly in 893 and does not mention the attack on Chester. The "Life" ends abruptly with no concluding remarks and it is considered possible that the manuscript which survives is an incomplete draft. Asser lived a further fifteen or sixteen years and Alfred a further six, but no events after 893 are recorded. No reason why Asser should suddenly stop work on the "Life" has ever been proven. It could be that Asser (who was Welsh, from St David's, Dyfed) had his own feelings about Alfred leaving the Vikings to devastate Brycheiniog, Gwent and Glywysing.

Not all accounts have Alfred personally involved with the Vikings at Chester and it may have been a military operation conducted by the Mercians (in which case the ASC would probably not mention them).

Æthelflæd

Æthelflæd was born around 870, the oldest child of King Alfred the Great and his Mercian wife, Ealhswith, who was a daughter of Æthelred Mucel, ealdorman of the Gaini, one of the tribes of Mercia. Ealhswith's mother, Eadburh, was a member of the Mercian royal house, probably a descendant of King Coenwulf (796–821). Æthelflæd was thus half-Mercian and the alliance between Wessex and Mercia was sealed by her marriage to Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians in around 886. Æthelred's descent is unknown. Richard Abels describes him as "somewhat of a mysterious character", who may have claimed royal blood and been related to King Alfred's father-in-law, Ealdorman Æthelred Mucel. In the view of Ian Walker: "He was a royal ealdorman whose power base lay in the south-west of Mercia in the former kingdom of the Hwicce around Gloucester". Alex Woolf suggests that he was probably the son of King Burgred of Mercia (who had been driven out by the Vikings) and King Alfred's sister Æthelswith, although that would mean that the marriage between Æthelflæd and Æthelred was uncanonical, because Rome then forbade marriage between first cousins. When Plegmund became archbishop the "sins" of the English nobles in intermarrying had been pointed out to him, but he appareently did little to oppose it.

The Roman city of Chester was refortified around 907 by the Mercians. The event is recorded in the Chronicle (although versions vary) and a cryptic note from 907 that "Chester was restored" suggests more fighting (or rebuilding) in that year :

- A.D. 907. This year died Alfred, who was governor of Bath. The same year was concluded the peace at Hitchingford, as King Edward decreed, both with the Danes of East-Anglia, and those of Northumberland; and Chester was restored.

Raphael Holinshead (writing in the 1570's) also mentions the same, adding that this was when the walls were extended by Æthelflæd - daughter of Alfred and sister to the King: