Amphitheatre

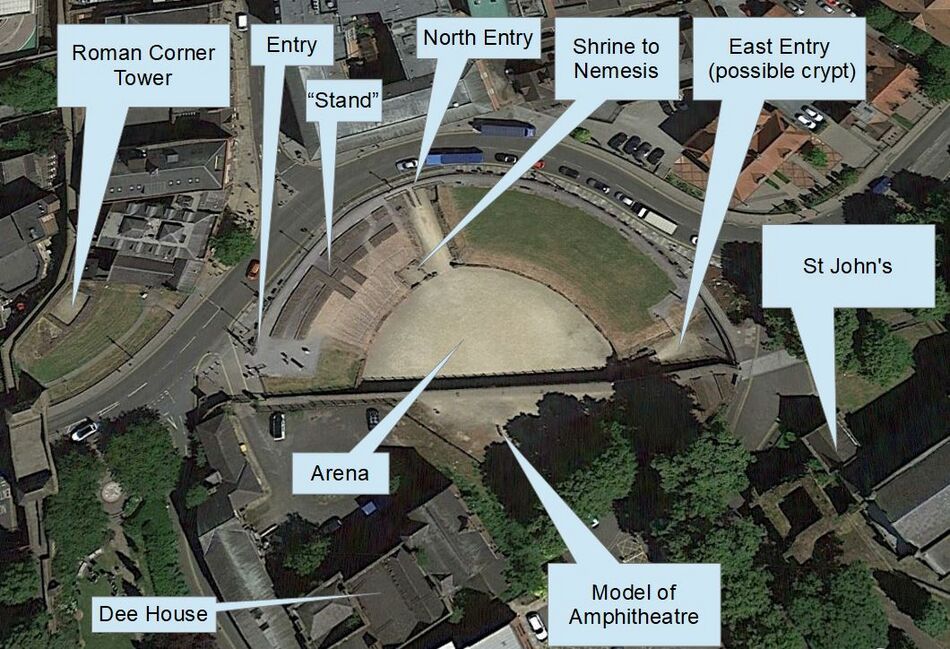

Roman amphitheatres are rare monuments in Britain, there being only twelve known examples. Chester's amphitheatre lay outside the south-east corner of the legionary fortress, on a bluff overlooking the River Dee. It was the largest stone-built Roman military amphitheatre in Britain. The main entrances faced north and south, with smaller entrances facing east and west. In between each of these entrances were two doorways giving access to a corridor running around the outside of the building and staircases leading up to the seats. The original structure was almost circular, but only half of it is now exposed above ground, giving it something of the appearance of a classical theatre (as used for comedy as well as tragedy) rather than the Colosseum-like structure that it was.

The Amphitheatre was a place of conflict and entertainment, and it is perhaps appropriate that discusssions of its history, as well as associated sites should be riddled with conflicts of facts and opinion. They are also stared at by the masses and entertain some. For the various conflicts over "to dig or not to dig" there is nothing better than Steve Howe's site. This article provides a short summary of what can be seen on the ground in modern times followed by a discussion of the possible developments associated with the site in the post-Roman period. One thread which runs through the story of the Amphiteatre at Chester is that you should perhaps not always take what is read as a given.

Building the Amphitheatre

The first amphitheatre was built in the 70s AD (or possibly as late as 86). It had a stone outer wall with external stairs and timber framed seating, the structure of which can be reconstructed. The second amphitheatre was built concentrically around the first, sealing deposits relating to the behaviour of spectators and the economy of spectacles in the first building. Amphitheatre 2, probably built in the later second century, was the largest and most impressive stone built amphitheatre in Britain, featuring elaborate entrances, internal stairs and decorative pilasters on the outer wall. There are larger amphitheatres built of earth banks - reusing earlier earthworks - but Chester is the largest one built from "scratch".

Roman Construction

There are two theories about the way the amphitheatre was built. One is that it was constructed completely from timber, and some time later rebuilt in stone. The other says that the amphitheatre was made from a mixture of wood and stone, with timberwork staging to support the front rows of seats. The most recent digging seems to support the latter view. The stone for the construction most likely came from quarries along the River Dee (see LIDAR image on the left).

Some time before the middle of the second century, the amphitheatre stopped being used, so it may only have been in service for 20 or 30 years. The arena became a rubbish dump and the building slowly fell into disrepair. It was brought back into use some time after the 270s, but only for a short time. The staircases up to the seats were repaired, a new surface was laid in the arena and the east entrance was drastically remodelled. One theory is that the amphitheatre was brought back in to use for a very special reason. In 287, the province of Britain revolted against the Roman Empire and was not reconquered until 296/7. One of the British legions was a strong supporter of the rebel governor, Marcus Aurelius Carausius. It has been speculated that this was Legio XX Valeria Victrix and that the amphitheatre could have been remodelled by the victorious government forces as a place of execution for the ringleaders, with the remainder of the disgraced legion – and perhaps local dignitaries – forced to watch. This seems like a highly unlikely speculation given the expense and effort which would have been involved in enlarging the Amphitheatre. A better explanation might be that much of the XXth legion was moved north to work on Hadrian's Wall after about AD 122, and Chester was neglected until they returned. The last actual evidence of Legio XX being at Chester comes from around 250 AD. In 255, a subunit of the XXth was fighting in Germania and, after its victory, sent to the Danube. The legion was still active during the reign of the usurpers Carausius and Allectus (286-293 and 293-296), but is not mentioned in the fourth century: perhaps it was disbanded when the Roman emperor Constantius I Chlorus reconquered and reorganised Britain.

Later Changes

The refurbished amphitheatre fell into decay again by the beginning of the 4th century and the site began to be used for other purposes. Two lean-to buildings against the arena wall were found during the 1960s, and postholes found in the middle of the arena could be the remains of a sub-Roman hall building. Featured on the eastern entrance of the amphitheatre are some very large sandstone blocks, together with the remains of steps on the south side. The masonry is unlike any other Roman work in Chester and the wear on the steps implies centuries of use. One suggestion is that the old entrance passage was converted in the Dark Ages into a crypt for an early version of St Johns Church. This is discussed in more detail below. By about 1200, people were living on the site, perhaps in the dilapidated shell of the Roman building. The area was cleared during the Civil War siege of Chester in the 1640s, and later the site was dominated by two large Georgian houses, built in the 1730s. One was St John’s House, which was demolished so that the northern half of the amphitheatre could be excavated; the other is Dee House, which still stands, in a partly ruinous state, over part of the southern half.

The Roman Amphitheatre: What to See

On the ground one can see what there is to be seen of the Amphiteatre itself in half an hour or less. There is some signage dotted around (some of which may be of dubious accuracy) but plans for an "interpretation centre" have come to nothing. There is a lot more to see (and think about) in close proximity to the Amphitheatre. On this site there is a guide to the City Walls which pass close by, a guide to the St Johns Trail which covers the area around the Amphitheatre and much else.

How to get there

The amphitheatre is situated at Little St John Street, Chester (click on the walking man above for a selection of maps and images). Access is available by foot every day and there are no set opening hours. Entrance is free.

The overall site

The structure consisted of a 40 feet (12 metre) high stone ellipse, 320 feet (98 metres) along the major axis by 286 feet (87 m) along the minor. The exits were positioned along the four points of the compass. Evidence of eight vaulted stairways, known as vomitoria, has been uncovered, which opened directly on to the street and served as entrances to the auditorium. As was the fashion with most Roman lay-outs of the era, the amphitheatre was placed at the south-east corner of the fort. Unlike other smaller, more basic amphitheatres in Britain, the one in Chester had proper seating for about 8-10,000 spectators on two storeys and about it stood a complex of dungeons, stables and food stands (including ovens).

A good place to start exploring the Amphiteatre is the western entry at the top of Souters Lane, near the Newgate. From here it is possible to see the remains of the Roman Corner Tower now located just outside of the City Walls. Originally this corner tower would be just within the City Walls of Roman Chester. The original Roman walls turned west here and would have run down the north side of Pepper Street. The Roman walls were extended down to the River Dee when Chester was refortified just after the time of Alfred the Great (around AD 907). The location of the Amphitheatre just outside the south-east corner of a Roman walled city/fortress is a common feature of the Roman design.

Start at the explanatory signage just inside the gate. What is obvious at once is that only less than helf of the Amphitheatre is visible. Three fifths of it is still underground, party beneath Dee House and the other structures to the south.

The "Stand"

Extending clockwise from the western entrance are a set of replica stone walls which indicate the positions of the bases of the walls of the amphitheatre. The inner walls are the first stone structure and the outer walls are the later expansion. These stone walls supported a wooden seating structure. It is not known whether there was any kind of awning above this structure to provide shade from the sun or shelter from the rain.

One set of very human archaeological finds in Chester are portable clay ovens. These may have been used rather like a "Tandoor", and while they may have been in common use by the legionaries, they might well have been used to provide food for the spectators at the amphitheatre.

Excavations in 2004-2006 of this area revealed the largest single fish bone assemblage in Roman Britain. The lower parts of the timber seating framework were held in place by dumped material from the arena and elsewhere. This material contained over 20,000 fish remains dating from the Roman to post-medieval period and there were over 4,500 fish remains dating to the Roman period. 27 different types of fish were represented. Fish was a prominent part of Roman diet and marked out those elements of the population who wanted to be ‘Roman’. Most of the British Iron Age population did not consume fish as a regular part of their diet. Over 70% of the remains were flatfish (mid-sized flounder and plaice). Eel was the second most commonly consumed fish at the site (15%) with salmon and trout the third most popular. The preponderance of freshwater and estuarine fish, indicate that most of the early fishing was local. There is little cod or herring indicating that fishing did not extend out into, for example, the deeper parts of Liverpool Bay. Spanish mackerel, a fish are not found in the waters around the British Isles was also found in the deposits. This fish occurs in thge coastal waters of Portugal, Spain and the north coast of Africa and possibly provided an imported taste of the Mediterranean to Chester’s Roman population in thr first century AD. Given the range of bones found it was most likely salted as whole fish. There were no butchery marks on the bones found suggesting that the fish was eaten on the bone and perhaps formed a meal for one or two people. There is also evidence to suggest that tastes, the environment or fishing methods changed over time. There is a trend to find smaller fish in the assemblage as time progresses into the 3rd century. Later remains contain almost no flatfish and eel and herring becomes more common.

As well as whole fish the Romans were fond of "Garum" a fish sauce. It can be argued that this later evolved into Worcestershire sauce: a savory sauce based upon fermented anchovies and other ingredients. Ketchup, originally a savory fish sauce which contained neither sugar nor tomatoes, shared its origins, culinary functions and popularity with garum.

Chicken bones have also been found, probably again from food sold on stalls next to the amphitheatre. It has been suggested that "souvenirs" might also have been on sale, possibly including articles of "millifiori" glass or ceramic ware depicting gladiatorial combat (remains of both have been found at the Amphitheatre site). The sale of these "souvenirs" may indicate that Roman Chester had "tourists" just like modern Chester and that a "day at the Amphiteatre" predated the more recent "day at the races". Like the modern race-goers, the Roman tourists probably drank a lot and possibly placed bets.

After examining the "stand" area, walk over to the stairs near the north entrance where there is some more signage. N.B. there is no way down into the central arena area for wheelchair users.

The North Entry

Beside the north entry of the amphitheatre stands a shrine to Nemesis, Roman godess of vengeance. During excavations the remains of a small, well-decorated alcove were found next to the innermost of the original support walls. This could have been the original location of the shrine, which was later moved to the location where it can be seen today, probably when the original amphitheatre was expanded. The first few steps on the opposite side of the entrance to the shrine are original Roman stone and led up to the platform above the entrance where the officials who controlled activities in the arena were placed.

The present altar is a replica; the valuable original is kept at the Grosvenor Museum. The text on the altar reads "DEAE NEMESI / SEXT MARCI / ANVS 7 EX VISV" ("The goddess Nemesis, Sextus Marcianus, centurion, from a vision" - "7" being a common abbreviation for centurion). In ancient Greek religion, Nemesis (Νέμεσις), also called Rhamnousia or Rhamnusia ("the goddess of Rhamnous"), was the goddess who enacts retribution against those who succumb to hubris. Rhamnous is the most famous site of worship for Nemesis.

The name Nemesis is related to the Greek νέμειν (némein), meaning "to give what is due", from Proto-Indo-European "nem-" (distribute). In some sense her Roman counterpart was Invidia, who was the patroness of gladiators, the goddess of jealousy as well as vengeance. Sources consistently named Nyx, the goddess of the night, as the mother of Nemesis, but were inconsistent on her father. Zeus, Oceanus, and Erebus have all been described as Nemesis’s father, while yet other sources claimed she had no father at all.

Nemesis was one of several patron deities of the Roman drill-ground (as Nemesis campestris). Modern scholarship offers little support for the once-prevalent notion that arena personnel such as gladiators, venatores and bestiarii were personally or professionally dedicated to her cult. Rather, she seems to have represented a kind of "Imperial Fortuna" who dispensed Imperial retribution on the one hand, and Imperially subsidized gifts on the other; both were functions of the popular gladiatorial public games (Ludi) held in Roman arenas. Altars to Nemesis have been found elsewhere. One, possibly from Housteads on Hadrian's Wall, bears the inscription: "nem͡esi | ap̣ollon|ivs sace|rdos fec" ("To the goddess Nemesis Apollonius, the priest, set this up"). Some have speculated that a stone now at All Saints parish church, Gresford is another altar to Nemesis.

Romanian archaeologists from Alba Iulia discovered a Roman temple dedicated to the goddess Nemesis within the fortress in the city. A statue of the goddess, a bas-relief and a votive altar were found inside the fortress. Having made whatever offering to Nemesis is thought appropriate, it is possible to walk out into the level area in the middle of the amphitheatre.

The Arena

During excavations a quantiry of yellow sand was found on the ground around the outside of the Amphitheatre. It is thought that this sand, which came from Boughton just to the east of Chester was used to floor the arena ("arena" is the latin word for sand). The colour may have been chosen so that blood would show up clearly! After some use the old sand would be removed and dumped while a new layer was put down. From the arena floor it is clear that the walls of the central part of the Amphitheatre are backed with concrete. This is not Roman concrete but was put in place during early excavation to keep the walls in place. Parts of the walls seen today have been extensively reconstructed.

A trompe l'oeil mural was commissioned in August 2010 by Chester Renaissance to enable visitors to experience the illusion of a complete amphitheatre as well as showing how the original structure may have looked. Archaeologists advised artist Gary Drostle on the original construction and found artefacts from the site. The artist designed an image that spanned the 50 metre walkway wall, starting with a continuation of the current amphitheatre edges that merged seamlessly into the recreation of the original walls and seating towards the centre. The painted ellipsis of the sand covered ground and depiction of the central tethering stone allow a viewer to experience a full immersion in the amphitheatre that was not possible with the previous, blank wall. Details such as the red, marble covered arena wall, position of the doorways and vomitoria (exits) and outside walls were all carefully recreated as the evidence suggested.

After finishing in the arena it is possible to exit the area via the eastern entrance and up some wooden steps. The names of the artists who created the mural are recorded on the wall here.

The East Entry

Parts of the east entrance consist of some quite large blocks of stone. It has been suggested that this would have been the location of the "official box" (above a passageway), or that this area has been modified by the construction of a crypt associated with the nearby Church of St Johns. Some of the recent (2019) signage from the east entry is discussed in more detail below. Close examination of the east entry reveals some features which may differ from the rest of the Amphitheatre. The stonework is more massive and the surface of the stones may be scored to provide a "key" for plasterwork. To either side there are remains of what may be stairs going both up and down, some of which are quite worn as if they have seen a lot of use. Several theories have been put forward to explain this. These include a "box" for dignitaries, the later use of the site as a defensive struture and conversion of the entrance into a crypt for the relics of martyrs. These are discussed in further detail below, although no firm conclusion can be reached.

Around and About

There is a little more to see to the south of the arena, above the remaining (still buried) part of the Amphitheatre. There is a good model of what the Amphitheatre would have looked like on completion. The sigbage on this is a little innaccurate as the Chester amphitheatre was not the largest in Roman Britain per-se, but was believed to be the largest masonry amphitheatre. There were larger amphitheatres made of earth banks, but in one case at least this was a re-used prehistoric earthwork and so the size of the amphitheatre it became was pre-determined. The benches near the model bear inscriptions which mostly have little to do with the amphitheare, except that one bears the words "SERANO LOCVS", which was found carved on a recovered coping stone from the wall and is believed to have been carved by a Roman named Serano(s) to indicate that this was his place (or perhaps carved in mockery of Serano).

Discovery and Excavations

Discovery

Interest in discovering Chester’s amphitheatre was stimulated by the excavations of the Caerleon amphitheatre in 1926-27. It's presence had been long suspected: William Thompson Watkin in his influential "Roman Cheshire" of 1889 (it was published after his death in 1888) wrote:

- "There remains the interesting question, where was the amphitheatre? A station or castrum of of the dimensions of Deva would certainly have one... It would certainly, at Deva as elsewhere, be outside of the Roman walls, and I suspect either at Boughton or at the 'Bowling Green' .. I hardly think it would be on the Handbridge side of the river, though we may look for discoveries of villas in that area. Time will probably reveal the locality, either by information being brought to light from old manuscripts or or from actual excavation accidentally taking place within its area".

No-one knew for certain that Chester had an amphitheatre until 1929, when a large curved wall appeared while an underground boiler room was being built onto the south side of Dee House, an eighteenth-century town house used as a convent school for girls. A local schoolmaster, W. J. Williams, was the first to recognise what this meant. Williams identified a stretch of masonry exposed in June 1929 as the outer wall of the amphitheatre. The curving wall and the buttresses were the main features that suggested that this was the amphitheatre, which proved to be well preserved. In the early 1930s, parts of the western entrance, the outer wall, the arena walls and the arena itself were discovered.

Further trenches dug by P H Lawson, who assumed that its dimensions would have been similar to those of the amphitheatre at Caerleon, confirmed the identification. Lawson’s carefully judged and small-scale trenches enabled an accurate assessment of its position and extent to be made. Further work took place in 1930-31 for the Chester Archaeological Society and the University of Liverpool, directed by Professors Newstead and Droop. They examined parts of the western entrance, perimeter and arena walls and the arena itself. Much of the structural history of the stone amphitheatre was established by their work. In 1934, more trial holes were excavated in the cellar of St John’s House and at 19 Little St John Street, which revealed parts of the northern outer wall of the amphitheatre.

Controversial proposals had been put forward in 1926 by the City Corporation to straighten Newgate Street and Little St John Street between the City Walls and St John's Church. Hostility to the scheme was increased by the discovery of the amphitheatre in 1929, when it was realised that the new road would cut directly across the centre of the monument. The City Improvement Committee delayed inviting tenders for the construction of the new road to allow the Chester Archaeological Society time to raise funds to cover the cost of diverting the road around the outside of the site, some £23,798. A special exhibition was held in 1932 at the Grosvenor Museum (which was then run by the Archaeological Society) to help raise money.

The walls lining the proposed road had been built, cutting the site in two, and a new gate through the Walls was under construction when the Ministry of Transport effectively blocked the scheme in 1933 by refusing loan sanction. This occurred as a result of extensive local and national protest at the imminent destruction of the amphitheatre; opponents of the scheme included the Prime Minister, Ramsay MacDonald. The Archaeological Society formed a Trust, which bought St John’s House, on the north-eastern corner of the monument, while the remainder of the northern half remained derelict for some years. The house was leased to Cheshire County Council from 1934 to 1957. The outbreak of war in 1939 led to the shelving of plans for the site’s imminent excavation. However, by the late 1950s, the income generated in rent from St John’s House had increased to a point that allowed it to consider the excavation of the northern part of the site, although financial help from the Ministry of Public Buildings and Works was necessary.

The archives for the 1920s and 1930s excavations have not been located and it is unlikely that the primary record of the earliest interventions survives. However, Chester Archaeology does have some of the drawings from the 1930s excavations and an article written at the time by Newstead and Droop is listed in the links below. The archives and finds from the 1960s excavation are stored in the Grosvenor Museum.

Post-war excavations

St John’s House was demolished in 1958. In the previous year, small-scale excavation had commenced, at the Ministry of Works’ request, to confirm the exact positions of the amphitheatre’s walls. Hugh Thompson, then curator of the Grosvenor Museum, carried out the work. This was to allow the Corporation to fix a final line for Little St John Street. Large-scale excavations followed between 1960 and 1969, still under the direction of Hugh Thompson, with the most detailed work after 1965, following the transfer of the St John's House site to state ownership. Dennis Petch, Hugh Thompson’s successor at the Grosvenor Museum, was also involved in some of the later work. The Ministry of Works funded most of the work, with help from the Archaeological Society.

Following these extensive excavations in the 1960s and full publication in 1976, the amphitheatre in Chester became a well-known monument, both locally and in the literature of Roman Britain. However, cursory examination of the site and the records of former excavations suggests that many of the published ‘facts’ are hypotheses that do not stand up to detailed questioning.

Controversial plans were put forward in the 1980s to excavate the remainder of the amphitheatre and reconstruct at least part of it as a heritage attraction. Permission was granted to demolish Dee House, a Grade II listed building, to allow the scheme to happen. It was to include a state-of-the-art interpretation centre, a reconstruction of part of the Roman structure and peripheral activities (including Roman galleys plying the River Dee and a café selling "Roman" food). Owing to lack of finance, the plans came to nothing and planning permission for the scheme lapsed in October 1995. The proposal to open the Dewa Roman Experience eventually happened - that attraction is at Pierpoint Lane (off Bridge Street), itself the site of Roman remains.

Chester Heritage Trust and the 1990s

Further development proposals were submitted to the then Chester City Council in 1993, involving the modification of the Dee House site, which had been sold by British Telecom to McLean Homes Ltd. Dee House itself and the gardens to its north were transferred to the ownership of Chester City Council, while the remainder was retained by McLean's. Permission was initially sought to demolish the 1929 extension to the south of Dee House with the intention of designing an office block to replace it.

Lancaster University Archaeological Unit was commissioned to undertake an archaeological evaluation of the entire site. Although the excavation was designed to extend no deeper than the top of ‘significant’ archaeology (defined in this instance as deposits that pre-dated the construction of Dee House in 1730), it proved difficult (and often unhelpful) to define this as the cut-off point. Twenty-eight trial trenches showed that preservation of the amphitheatre varied across the site. Beneath the eighteenth-century house, extensive cellarage had destroyed all but the foundation deposits, while outside and beneath the 1920s extension, preservation was much better. Following the evaluation, the scheme was granted planning permission in 1995.

A second phase of evaluation took place in 1994, conducted by Chester Archaeology, following a further application to lower the car park area to the east and south-east of the historic core of Dee House. Only those deposits that would be affected by the proposals were evaluated. They were found to consist largely of garden soils and features associated with gardening practices, including the substantial remains of three greenhouses dating from the later 19th century.

Excavations since 2000

The beginning of site work in February 2000 caused further controversy, when construction began on the office block that had been granted permission in 1995. Many local residents were outraged at what they perceived as the "loss" of the amphitheatre to excavation, demanding that the site be completely uncovered and displayed. The controversy extended from the local press into national media (for instance The Daily Telegraph, 18 April 2000).

The controversy focused on a number of discrete elements:

- The construction of a new building over a part of the amphitheatre (an area of around 174 m2);

- An alleged change of use from non-specific offices to County Court;

- An alleged lack of public consultation during the original consideration of the 1993 Planning Application;

- English Heritage policy on the preservation rather than excavation of archaeological sites;

- An alleged lack of investment in displaying the city’s Roman archaeology.

The issues are well-recorded on Steve Howe's website (see link below).

Since the excavations began, a number of discoveries have been made. Chester’s Roman amphitheatre was in fact a grand two-storey structure, the only one of this kind in Britain but similar to those found in parts of the Mediterranean, and was built on the foundations of a second, earlier theatre. This small stone amphitheatre was constructed first with wooden seating and has been dated to around the reign of the emperor Vespasian, by the discovery of a single Roman coin found in a sand surface outside the first amphitheatres stone wall.

This initial amphitheatre was replaced with a much larger and grander amphitheatre, with stone buttresses and arches. It would have been an impressive sight when viewed from the river below. The excavations found eight ‘vomitoria’, or entrance points, spaced evenly around the amphitheatre with two in each of its quadrants. They would have been housed in internal staircases running outside the structure’s walls, indicating that it had two storeys. Estimates put the seating capacity of the two-floor amphitheatre at between 8-10,000 spectators, suggesting that Roman Chester could have had a substantial civilian population.

Evidence for gladiatorial combat have also been found in the shape of part of a gladius sword handle. Also parts of a Roman bowl showing scenes from a gladiator fight have been found. Also discovered was a stone block with an anchor point for a chain. It has been speculated that wild animals or indeed people would have been chained to this block during the 'spectacular'.

The Chester Amphitheatre Project, initiated in 2004, was established to better understand the Roman amphitheatre itself, and also the development of the subsequent urban landscape which was influenced by the presence of the Roman structure. The work revealed that the site has a much greater time-depth than previously understood. The earliest settlement was Mesolithic (c 6000 BC), and the evidence for this was almost ploughed away by Iron Age farmers. The Iron Age field systems, together with a round-house and a granary have been radiocarbon dated to 400-200 cal BC. The Iron Age agricultural landscape survived because it was buried by the earthworks of the first Roman amphitheatre, built in the AD 70s.

Future proposals

It has been recently proposed to turn the amphitheatre into an open air concert venue. In 2016 the Council approved plans to grant a 150-year lease for Dee House, meaning that the still-buried half of the Amphitheatre will not be excavated. Reasons for the decision included the argument that much of what is visible today is actually reconstruction and it is likely that very little remains under Dee House. By 2018 the plans to develop Dee House had fallen through as the builing is in such a fire-damaged and unsafe condition the holders of the lease found it uneconomic to carry out the proposed works. In 2020 a working group concluded, after a broad consultation that it would be impractical to seek permission to demolish Dee House, that the building was too unsafe to survey internally and that it would be difficult to turn it into a heritage centre.

The Amphitheatre and St Johns

The Amphitheatre at Chester may have played a significant part in the history of Chester long after the Romans departed and through the Dark Ages, but perhaps not as the signage at the Amphitheatre suggests. There are two polarised views on this: first that in the anarchy which followed the withdrawal of the Roman legions, the site, untenable by a small force, was neglected and left derelict, its true value only fully appreciated in the military reorganisation of the Mercian Kingdom at the beginning of the 10th century. The second view is that Chester remained an important ecclesiastical center throughout much if not all of the Dark Ages. The Amphitheatre is a good place to consider the difference between historical "truth" and/or any combination of deliberate deception, misinterpretation, myth, folk-tale and legend. One key puzzle relates to the Viking assault on Chester around 893 which is discussed in some detail below. In some places the story as told below has been simplified by leaving out details of parts of the campaign and as told the story concentrates of matters involving Chester. Full details of the parts left out can be found by following the links. The gist of the puzzle is whether Chester was inhabited at the time of the Viking assault. A related puzzle is why Asser's "Life of Alfred" breaks off suddenly at the time of the assault on Chester and does not mention it at all.

A suitable starting point for the story is the invasion by the "Great Heathen Army" in 865. This was a coalition of "Norse" warriors, originating in Denmark but also from Norway and Sweden, who came together under a unified command to invade the four Anglo-Saxon kingdoms that then constituted England. Since the late 8th century, the Vikings had primarily engaged in "hit-and-run" raids on centres of wealth such as monasteries. The Great Heathen Army was distinct from these raids in that it was much larger and formed to occupy and conquer large territories. Legend has it that the force was led by four of the five (or more) sons of Ragnar Lodbrok, including Hvitserk, Ivar the Boneless, Bjorn Ironside and possibly Ubba. There is no hard evidence that Ragnar actually existed under this name and outside of the mythology associated with him.

The 1958 film The Vikings is based on Edison Marshall's historical fiction 1951 novel, in which Ragnar (played by Ernest Borgnine) is captured by King Ælla of Northumbria and cast into a pit of wolves; a son named Einar [sic] (played by Kirk Douglas - also known for his role as the gladiator Spartacus) vows revenge and conquers Northumbria with help from half-brother (and sworn enemy) Eric (played by Tony Curtis) who also had much to avenge upon King Ælla. The film is full of historical innacuracy: starting with scenes from the Bayeux tapestry (made more than 200 years later) and Einar romping around a Viking village and making out with a Scandinavian babe atop a heap of pelts, while wenches brew ale in barrels the size of skips, hairy old men hurl axes at their wives, and small children run around wearing reindeer-skin nappies.

Ælla of Northumbria (fl. 866; d. 21 March 867) was a real historical character and took part in the seemingly endless dynastic feuds in Northumbria being opposed by Osberht (who was possibly his brother). According to the Historia Regum Anglorum, following the invasion of the Danes, the previous "dissension" between Osberht and Ælla "was allayed by divine counsel" (and presumably other Northumbrian nobles). Osberht and Ælla "having united their forces and formed an army, came to the city of York" on 21 March 867. A majority of the "shipmen" (Vikings) gave the impression of fleeing (a ruse). "The Christians, perceiving their flight and terror", attacked, but found that the Vikings "were the stronger party" (were tricked into an ambush). Surrounded, the Northumbrians "fought upon each side with much ferocity" until both Osberht and Ælla were killed. The surviving Northumbrians "made peace with the Danes" (surrendered and paid-up).

While Ragnar is almost certainly fictional his "sons" do appear to be real historical characters:

- Hvitserk - eventually burned at the stake;

- Ivar the Boneless - "Ívarr beinlausi" could be translated to "Ivar legless", but "beinlausi" could also be translated as "boneless";

- Björn Ironside - securely dated between 855 and 858;

- Halfdan Ragnarsson - the first Viking King of Northumbria and a pretender to the throne of Kingdom of Dublin. He died at the Battle of Strangford Lough in 877 trying to press his Irish claim;

- Ubba - features in several dubious hagiographical accounts of Anglo-Saxon saints and ecclesiastical sites. He possibly died at the Battle of Cynwit;

The invasion

Major Danish invasions took place in 865. The campaign of invasion and conquest against the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms lasted 14 years and resulted in almost the complete conquest of Britain. Although eventually fought to a stalemate by a resurgent Alfred of Wessex, the Danes were not evicted from all of their conquered teritory and retained considerable land to the east of the country. This has been seen as a pivotal moment in English history and both the historic events and the later views of them are worth some consideration.

The invaders initially landed in East Anglia, where the king (later to become Edmund the Martyr) provided them with horses for their campaign in return for peace. Estimates of the size of the army vary with many clustered around 3000 men. To put this into perspective the sides at the Battle of Hastings numbered 12-13,000 each. That was a large battle for its time and later battles did not have significantly larger forces on the two sides (compare Bosworth: ~10,000; Rowton ~4000). Another way to put this into context is to compare the area the Danes/Vikings eventually controlled (maximally 30,000 square miles) with the size of their force (at most 3,000). This gives a "Viking density" of one for every ten square miles. To add some further context the Burghal Hidage a detailed picture of the network of fortified "burhs" that Alfred the Great later designed to defend his kingdom from the predations of Viking invaders, required his subjects to provide one fully armed soldier in the king's service for every square mile (five hides).

They spent the winter of 865–66 at Thetford, before marching north to capture York in November 866. York had been founded as the Roman legionary fortress of Eboracum and revived as the Anglo-Saxon trading port of Eoforwic - the Danes installed a puppet ruler (Ecgberht I) in Northumbria. During 867, the army marched deep into Mercia and wintered in Nottingham. The Mercians agreed to terms with the Viking army, which moved back to York for the winter of 868–69. In 869, the Great Army returned to East Anglia, conquering it and killing its king Edmund. Edmund later became the he of Bury St Edmund. The army moved to winter quarters in Thetford again. In 871, the Vikings moved on to Wessex, where Æthelred I (brother of Alfred the Great) paid them to leave. The army then marched to London to overwinter in 871-2. The following campaigning season the army first moved to York, where it gathered reinforcements. This force campaigned in northeastern Mercia, after which it spent the winter at Torksey, on the Trent close to the Humber. The following campaigning season it seems to have subdued much of Mercia. Burgred, the king of Mercia, fled overseas and Coelwulf, described in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle as 'a foolish king's thegn' (a puppet) was imposed in his place.

The army spent the following winter at Repton on the middle Trent, after which the army seems to have divided. Repton is one of the few places where a Viking winter camp has been excavated. Excavations from 1974 to 1988 found a D-shaped earthwork on a bluff, overlooking an arm of the River Trent, and opened a mound containing a mass grave. The mass grave contained the remains of at least 264 individuals. The bones were disarticulated and mostly jumbled together. Forensic study revealed that the individuals ranged in age from their late teens to about forty, four men to every woman. Five associated pennies fit well with the overwintering date of 873–74. The absence of injury marks suggest that the party had perhaps died from some kind of contagious disease, which raises the possibility that there was a plague raging in the Viking camp.

One group of Vikings seems to have returned to Northumbria, where they settled in the area, another group seems to have turned to invade Wessex. By this time, only the kingdom of Wessex had not been conquered. A group left Repton in 874 and established a base at Cambridge for the winter of 874–75. In late 875 they moved onto Wareham, where they raided the surrounding area and occupied a fortified position. Asser reports that Alfred and his brother made a treaty with the Vikings to get them to leave Wessex. The Vikings left Wareham, but it was not long before they were raiding other parts of Wessex, and initially they were successful. Alfred fought back, however, and eventually won victory over Guthrum at the Battle of Edington in 878.

Alfred's victory in some ways reads like something out of Tolkien. At one point he is the classic trope of an almost defeated king hiding in the woods and then gathers his troops at a historic location - Egbert's Stone - to go on to victory. The Tolkein version is the "Stone of Erech".

The account of the Welsh monk Asser written after 894 makes it appear that Alfred's victory was more total than it probably was. In reality Wessex and the Vikings probably fought each other to a statemate and continued with diplomacy. In 886, the Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum defined the boundaries of their two kingdoms. The kingdom of Mercia was divided up, with part going to Alfred's Wessex and the other part to Guthrum's East Anglia. Guthrum reigned as king in East Anglia until his death in 890, and although this period was not always peaceful he was not considered a threat.

Alfred and Chester

In around 894 there was a further invasion by the Danes which involved a forced march on Chester and possibly the occupation of the Amphitheatre. It has been suggested that Chester was an important site at the time and therefore replete with potential loot. An alternative view is that Chester was deserted at the time.

In 892 (or 893) the Danes again attacked Britain in force. Finding their position in mainland Europe (on the French coast) precarious, this new horde crossed to England in 330 ships in two divisions. They entrenched themselves, the larger body, at Appledore, Kent and the lesser under Hastein, at Milton, also in Kent. The invaders brought their wives and children with them indicating a meaningful attempt at conquest and colonisation. Alfred, in 893 or 894, took up a position from which he could observe both forces. Since the earlier raid Alfred had establish fortified towns under his "burh" system and these provided a much better defence than before. After some confused fighting they made a sudden dash across England and occupied Chester. The following account appears in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle:

- Þa hie on Eastseaxe comon to hiora geweorce. 7 to hiora scipum. þa gegaderade sio laf eft of Eastenglum, 7 of Norðhymbrum micelne here onforan winter 7 befæston hira wif, 7 hira scipu, 7 hira feoh on Eastenglum, 7 foron anstreces dæges 7 nihtes, þæt hie gedydon on anre westre ceastre on Wirhealum, seo is Legaceaster gehaten; Þa ne mehte seo fird hie na hindan offaran, ær hie wæron inne on þæm geweorce; Besæton þeah þæt geweorc utan sume twegen dagas, 7 genamon ceapes eall þæt þær buton wæs, 7 þa men ofslogon þe hie foran forridan mehton butan geweorce, 7 þæt corn eall forbærndon, 7 mid hira horsum fretton on ælcre efenehðe. 7 þæt wæs ymb twelf monað þæs þe hie ær hider ofer sæ comon. (As soon as they came into Essex to their fortress, and to their ships, then gathered the remnant again in East-Anglia and from the Northumbrians a great force before winter, and having committed their wives and their ships and their booty to the East-Angles, they marched on the stretch by day and night, till they arrived at a western city in Wirral that is called Chester. There the army could not overtake them ere they arrived within the ramparts: they besieged the ramparts though, without, some two days, took all the cattle that was thereabout, slew the men whom they could overtake outside the ramparts, and all the corn they either burned or consumed with their horses every evening. That was about a twelvemonth since they first came hither over sea.)

The Chronicle of John Brompton, seems to be the first work to mistakenly have Chester Castle in existence prior to the Norman Earls of Chester. This error was copied by many later authors. The Victorian work "Picturesque England", following Brompton, describes the fortifications at Chester of Alfred's time of being a round sandstone castle:

- The Danes, the following and more terrible invaders, who had been allowed by Alfred the Great to settle in Northumberland, next assailed Chester, and seized the fortress, which was circular and of red stone...

In fact the Danes who attacked Chester were not from Northumberland but encamped in the south. The Danes in Northumbria had not been allowed to setttle there by Alfred, but had conquered it. The obvious puzzle here is why the Danes should suddenly rush across the country from Shoeburyness on the Thames estuary in Essex to Chester. The Danes were coastal raiders who usually targeted a rich source of portable loot - the Danes from Northumberland were busy attacking Exeter (Roman Isca) which Alfred had fortified as a "burh" and north Devon. Alfred had driven the Danes out of Exeter in 877 after they had occupied it for a year.

It has been suggested that Chester was not a deserted city at the time that the Vikings fled there, and that they did not occupy the city itself but only the ruins of the Amphitheatre, which may or may not have been converted into a fortified dwelling. Whatever interpretation is taken leads to difficulties. On the one hand, Alfred does not engage the Vikings in a pitched battle at Chester but simply kills a few stragglers and burns all available supplies leaving the Vikings to starve after investing them for only a few days. This presents problems as to what any inhabitants of Chester might have been doing at the time and more importantly what they did over the winter, with Vikings camped on their doorstep and all local food apparently destroyed. On the other hand, if Chester was deserted then why is devastation of the Churches etc not recorded.

So Why Chester?

The Viking force which attacked Chester was commanded by "Hastein" a notable Viking chieftain of the late 9th century who made several raiding voyages. During 859–862, Hastein jointly led an expedition with Björn Ironside. A fleet of 62 ships sailed from the Loire to raid countries in the Mediterranean. Eventually he decided to sack Rome, but mistakenly attacked the city of Luna (modern Luni). He tricked his way in by pretending to be a dying Christian convert. Hastein then leapt from his coffin and decapitated a priest before joining his men. According to the traditional version upon finding that the city he had sacked was in fact Luna and not Rome, Hastein was so embarrassed that he massacred everyone there.

Settled back in Brittany, Hastein allied himself with Salomon, King of Brittany against the Franks in 866, and as part of a Viking-Breton army he killed Robert the Strong at the Battle of Brissarthe near Châteauneuf-sur-Sarthe. In 867 he went on to ravage Bourges and a year later attacked Orléans. Peace lasted until spring 872 when the Viking fleet sailed up the Maine and occupied Angers, which led to a siege by the Frankish king Charles the Bald and a peace being agreed in October 873. Hastein remained in the Loire country until 882, when he was finally expelled by Charles and then relocated his army north to the Seine. There he stayed until the Franks besieged Paris and his territory in the Picardy was threatened. It was at this point he became one of many experienced Vikings to look to Britain for riches and plunder. Given the time-span involved there may be more than one "Hastein" as he would have been very old during his British campaign. The Norman monk Dudo of Saint-Quentin wrote of Hastein:

- "This was a man accursed: fierce, mightily cruel, and savage, pestilent, hostile, sombre, truculent, given to outrage, pestilent and untrustworthy, fickle and lawless. Death-dealing, uncouth, fertile in ruses, warmonger general, traitor, fomenter of evil, and double-dyeded dissimulator ..." Dudo of St. Quentin's. Gesta Normannorum. Book 1. Chapter 3

There are several possible reasons why the Vikings might have marched to Chester, but there is scant evidence to choose between them. One important consideration is that when the Vikings arrived from France they brought their wives and children with them. It is not known for certain whether these wives and children were with the Vikings who marched on Chester, although they appear to have left these in East Anglia. It is very highly improbable that Hastein mistook Chester for Rome, but here are some possible scenarios:

- They didn't have a reason, they were just running away. The Viking base at Benfleet had been wiped out and Haesten's army could not risk an attack on Wessex as it was defended by the "burh" system. So it is possible that while Alfred was busy in Devon they decided to make a raid into less well-defended Mercia. A first raid failed and a second appears to have been directed more or less straight at Chester. There is little to suggest that the Vikings had another objective in mind and were forced to retreat on Chester by the forces of Wessex and her allies.

- They believed the city to be rich in plunder, possibly with a mint. The translation of Werburgh to Chester might suggest it was a place of some importance and hence a potential source of loot. St Johns is very likely to have existed by this time. During the later reign of Athelstan Chester appears to have been a more productive mint than London, but there is no evidence that Chester had a mint prior to 900.

- They believed the area to be deserted and suitable for settlement. If Chester was deserted then it may well have appealed to the Vikings as a place to settle. Like York it had the remains of a Roman fortress and good connections with the sea. It was far from Wessex and closer to Northumbria, which the Vikings had conquered. It would have made an ideal base which could be re-fortified and used as a base to attack Mercia.

- They were trying to link-up with potential allies. Potential allies were the Hiberno-Norse in Ireland and the petty Kingdoms of North Wales. There does not appear to have been extensive Viking settlement on the Wirral at this time, but there may already have been an active Viking trade port at Meols.

- They had allies in Chester. The 1849 translation Roger of Wendover (died 6 May 1236) confuses Chester with Leicester (but refers to it being on the Wirral). Wendover states that after the Battle of Buttington (893): "Those who escaped the slaughter fled to Leicester, whose English name is Wyrhale, where they found numbers of their countrymen in a certain town, and were admitted by them into their fraternity. On arriving there, the king, not being able to lay siege to the place, burned all the corn and victuals which he found without the town.. ..In the year of our Lord 896, the wicked band of pagans quitted Leicester and made for Northumberland, and there taking ship, they began again to roam the seas." Note that Roger of Wendover suggests that the Vikings were already occupying Chester, that "the king" laid siege to the city and that the Vikings apparently stayed until 896.

In the autumn the besieged army left Chester, marched down to the south of Wales and devastated the Welsh kingdoms of Brycheiniog, Gwent and Glywysing, until the summer of 894. The Vikings apparently return via Northumbria, the Danish held midlands of the Five Burghs, and East Anglia to return to the fort at Mersea Island. In the autumn of 894, the army towed their ships up the Thames to a new fort on the River Lea. In the summer of 895 Alfred arrived with the West Saxon army, and obstructed the course of the Lea with a fort either side of the river. The Danes abandoned their camp, returned their women to East Anglia and made another great march across the Midlands to a site on the Severn (where Bridgnorth now stands), followed all the way by hostile forces. There they stayed until the spring of 896 when the army finally dispersed into East Anglia, Northumbria and according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, those that were penniless found themselves ships and went south across the sea to the Seine.

Curiously, Asser's "The Life of King Alfred" breaks off suddenly in 893 and does not mention the attack on Chester. The "Life" ends abruptly with no concluding remarks and it is considered likely that the manuscript is an incomplete draft. Asser lived a further fifteen or sixteen years and Alfred a further six, but no events after 893 are recorded. No reason why Asser should suddenly stop work on the "Life" has ever been proven. It could be that Asser (who was Welsh, from St David's, Dyfed) had his own feelings about Alfred leaving the Vikings to devastate Brycheiniog, Gwent and Glywysing.

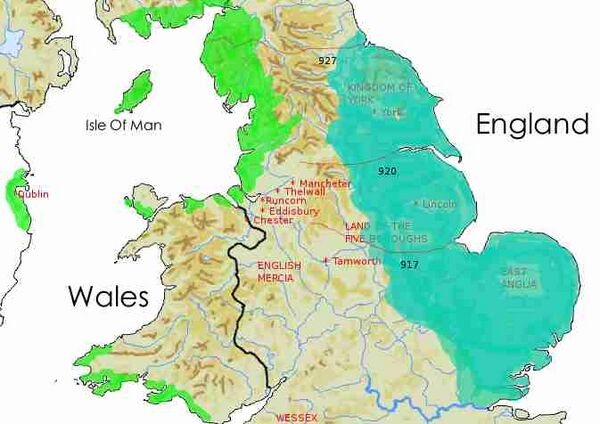

Refortification

The Roman city of Chester was refortified around 907 by the Mercians. The event is recorded in the Chronicle (although versions vary) and a cryptic note from 907 that "Chester was restored" suggests more fighting (or rebuilding) in that year :

- A.D. 907. This year died Alfred, who was governor of Bath. The same year was concluded the peace at Hitchingford, as King Edward decreed, both with the Danes of East-Anglia, and those of Northumberland; and Chester was restored.

Raphael Holinshead (writing in the 1570's) also mentions the same, adding that this was when the walls were extended by Æthelflæd - daughter of Alfred and sister to the King:

- Not without good reason did king Edward permit vnto his sister Elfleda the gouernment of Mercia, during hir life time: for by hir wise and politike order vsed in all hir dooings, he was greatlie furthered & assisted; but speciallie in reparing and building of townes & castels, wherein she shewed hir noble magnificence, in so much that during hir government, which continued about eight yéeres, it is recorded by writers, that she did build and repare these Tamwoorth was by hir repared, Eadsburie and Warwike towns, whose names here insue: Tamwoorth beside Lichfield, Stafford, Warwike, Shrewsburie, Watersburie or Weddesburie, Elilsburie or rather Eadsburie, in the forrest of De la mere besides Chester, Brimsburie bridge vpon Seuerne, Rouncorne at the mouth of the riuer Mercia with other. Moreouer, by hir helpe the citie of Chester, which by Danes had beene greatlie defaced, was newlie repared, fortified with walls and turrets, and greatlie inlarged. So that the castell which stood without the walls before that time, was now brought within compasse of the new wall.

The dates here are important. Alfred has his first major fight with the Danes (under Guthrum) in 871-875 at the time that the remains of St Werbergh were tranferred to Chester. Alfred has his second major fight with a fresh wave of Danes in around 894, just after Guthrum's death. In 900 Alfred died and his son Edgar the Elder was consecrated at Kingston-upon-Thames by the archbishop of Canterbury, Plegmund (of St Plegmund's Well fame). In 902, Alfred's daughter Æthelflæd is effectively ruling Mercia and a Hiberno-Norse community settles in Wirral after its expulsion from Dublin. In 907 Chester was "rebuilt" by Æthelflæd. Around 912 Chester is besieged by Ingamund and he is defeated.

Alfred appears to have introduced the "burh" system after 875, following his defeat of Guthrum. The "burhs" (the plural is "byrig") comprised a series of fortified towns to provide a place of refuge for the Anglo-Saxon rural population who lived within a roughly 20-mile (32 km) radius of each town. They also provided secure regional market centres and soon after their establishment the coinage was reminted every six or seven years by moneyers in about sixty of the burhs. The system developed more or less simultaneously in Wessex, France and Spain.

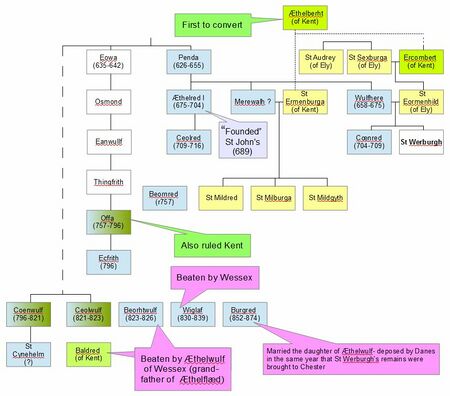

Æthelflæd and Werburgh

A late tradition holds that Æthelflæd promoted the cult of Werburgh at Chester. Chester already had connections with Werbergh: St Johns was possibly founded in her time and her remains were relocated in Chester during the time of the first major Danish invasion.

According to Henry Bradshaw (writing c.1513), Æthelflæd, enlarged the original church that is now the Cathedral in honour of St. Werburgh and transferred the original dedication to Peter and Paul to a new parish church in the centre of the city, but Bradshaw also mentions that a tablet in St John's church ascribed the foundation of the house of canons to Æthelflaed's nephew, Edmund (921-946). King Athelstan has also been credited with the foundation, since Higden (in his Polychronicon) states that there were secular canons serving St. Werburgh at Chester from the time of Athelstan until the arrival of the Normans. Of the three rival founders Æthelflæd, who, with her husband Ethelred, restored the city in 907, is the most likely, although there is no definite evidence of the existence of a church of canons dedicated to St. Werburgh at Chester before 958. In that year Edgar the Pacific, then king of the Mercians, granted to "the familia of St. Werburgh" 17 hides of land in Hoseley (Flints.), Cheveley, Huntington, Upton, Aston, and Barrow.

The problem with the re-location of Werburgh is that while it is mentioned by Bradshaw, it is not mentioned in either the brief biography written by Florence of Worcester (died 1118) nor by Goscelin, her hagiographer (who was alive in 1106). This was not Werbergh's first post-mortem journey. She died at Trentham (3 February, 699 or 700) and, according to some, was originally buried there. Existence of this nunnery is disputed and a connection with Saint Werburgh is also disputed. As for a leter Chester connection Trentham became an Augustinians monastery house from the 1150s, under the patronage of Ranulph De Gernon, Earl of Chester.

There are two versions of what followed Werbergh's burial. In the first Werburgh had apparently decided on Hanbury as her final resting place but happened to be at Trentham when she died. The nuns at Trentham refused to give up the body and even instituted security arrangements to prevent its removal. Despite this an expedition from Hanbury succeeded in "miraculously" recovering her remains. According to the second version her brother decided that Werburgh should be moved to the more important site at Hanbury. The shrine of St Werberh remained at Hanbury until the threat from Danish Viking raids in the late 9th century prompted their relocation to within the walled city of Chester. As recorded in the Annales Cestriensis:

- In the same year, when the Danes made their winter quarters at Repton after the flight of Burgred, king of the Mercians, the men of Hanbury, fearing for themselves, fled to Chester as to a place which was very safe from the butchery of the barbarians, taking with them in a litter the body of S Werburgh, which then for the first time was resolved into dust.

As noted above, the men of Hanbury may not only have feared the violence of the Vikings at Repton but may also have been concerned about the fact that the Vikings were dropping like flies from what may well have been a plague in their winter quarters.

Æthelflæd's choice of Werbergh is explainable. Historians have noted the remarkably high incidence of princess saints and abbesses descended from the Mercian line. It appears that the promotion of cults of members of the royal house was part of the Mercian policy for strengthening control of the satellite provinces. Æthelflæd's mother was Mercian and may have transmitted knowledge of how the Mercian court worked. Even the name of the saint was apt, for Werburgh in Anglo-Saxon means "Protectress of the Burh".

The "shrine" of Werburgh at the Cathedral in Chester is not actually the box in which Werburgh's relics were contained. This has been lost over the years although the Cathedral does contain the "shrine" erected in the 14th Cent, converted into a throne, converted back and moved several times, finding its present position in 1888. Bradshaw claims that the shrine (with relics) was in existence in 1180. However the relics were probably removed at the reformation. From as early as 1536 the clergy were required to preach against superstitious images, relics, miracles and pilgrimages. If the shrine containing relics survived into the time of Elizabeth I then had little change of surviving further as in 1559 Acts were passed that holy tables should be substituted for stone altars and that all shrines should be destroyed. Royal Commissioners were sent round the northern Dioceses to see that the Acts were enforced and they carried with them Elizabeth’s Injunctions. The Commissioners reached Chester Diocese at the end of September, 1559. They sat at Northwich on October 20th, but there the chief Commissioners fled for fear of the plague, appointing local laymen as their deputies. These sat in Tarvin church on October 24th and in the Cathedral on the 26th.

Æthelflæd and Oswald

There is rather more evidence to link Æthelflæd with Oswald, the second saint associated with the Cathedral at Chester but also having links to St Johns.

After successful raids by Danish Vikings, significant parts of North-Eastern England, formerly Northumbria, were under their control. Danish attacks into central England had been resisted and effectively reduced by Alfred the Great, to the point where his son, King Edward of Wessex, could launch offensive attacks against the foreigners. Edward was allied with the Mercians under his sister Æthelflæd, and their combined forces were formidable. The allies launched a five-week campaign against Lindsey in 909, and successfully captured the relics of Saint Oswald of Northumbria from Bardney Abbey in Lincolnshire. According to tradition Bardney Abbey was a Benedictine monastery founded in 697 by King Æthelred of Mercia (the founder of St Johns and uncle to Werburgh), who was to become the first abbot, but according to Bede the abbey already existed when Oswald was interred there in 679. A problem arises from the fact that the monastery was supposedly destroyed during a Danish raid in 869. Queen Osthryth (who brought the remains of Oswald, her uncle, to the abbey and is herself buried there) was murdered in 697 by certain Mercian nobles, and a few years later her husband Ethelred, like many other princes of his race, renounced the world and became a monk at Bardney. He was living there as abbot in 704, and was able to show much kindness and hospitality to St. Wilfrid, who came to the monastery in that year as a guest, bearing the papal letters which were meant to reinstate him in his see. There are clear connections between Bardney and both St Johns and Werburgh.

The bones supposedly recovered from Bardney were translated to the new Gloucester minster, which was renamed St Oswald's Priory in his honour. Both Æthelred and Æthelflæd were buried there. Oswald had died on the 5th August 641 at the Battle of Maserfield - the site of the battle is traditionally identified with Oswestry; arguments have been made for and against the accuracy of this identification. However there is no doubt as to the date, which became Oswald's feast-day.

Æthelflæd's husband was Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians who may have died as a consequence of wounds obtained at the Battle of Tettenhall (although he appears to have been ill for some time). The Battle of Tettenhall (sometimes called the Battle of Wednesfield or Wōdnesfeld) took place, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, near Tettenhall on 5 August 910. The allied forces of Mercia and Wessex met an army of Northumbrian Vikings in Mercia. It saw the crushing defeat of the last of the large Danish Viking armies to ravage England, including the deaths of the Danish Kings of York, Eowils and Healfdan. Æthelflæd may well have been influenced by the co-incidence of dates to add Oswald to the dedication of the new minster at Chester. However the puzzle remains as to how Oswalds relics survived from 869 to 909.

The parish of St. Oswald, king and martyr, originated in association with the minster church which eventually became the Benedictine abbey of St. Werburgh. The parish was termed indifferently St. Oswald's and St. Werburgh's in the 13th century, when the parishioners used the altar of St. Oswald in the abbey nave as their chief place of worship. The parish possessed burial rights in the city and its environs, originally shared only with St. John's, the other early minster church in the city. Besides the churchyard south of the abbey nave, it had by the later 12th century a cemetery outside the Northgate, associated with the chapel of St. Thomas of Canterbury and served by the monks of St. Werburgh's. Its burial rights were guaranteed by agreements with St. John's and by a papal bull in the late 12th and 13th century. The parish probably originally comprised much of the city together with a sizeable extramural territory. After other parishes were carved out of it, it covered a large discontinuous area embracing the north-east part of the walled city, the abbot's manor of St. Thomas outside the Northgate, and, beyond the liberties, to the north Bache, Newton, Croughton, Wervin, and Crabwall (in Blacon township), and to the east and south-east Great Boughton, Churton Heath, Huntington, Lea Newbold, and Saighton; further afield lay Iddinshall and Hilbre Island.

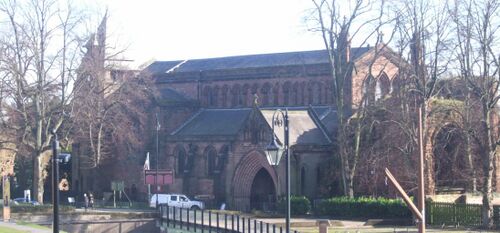

St John's

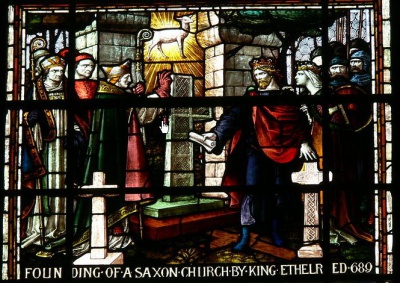

St Johns stands right next to the Amphitheatre in a seemingly undefended position outside of the City Walls. Despite the belief that St Johns only became a Cathedral after the Norman conquest there is evidence that it was a Bishop's see prior to the conquest. St Johns has clear connections with both Oswald and Werburgh.

Tradition ascribes the foundation of St. John's to Æthelred, king of Mercia (674–704), in 689. The direct authority for this statement quoted by John Leland is the Itinerary of Giraldus Cambrensisc. However no such information is found in the surviving texts of the Itinerary (it was written in 1191). Two authorities of a subsequent date quote the early date in such a mannner as to imply their acceptance of it, and the source as being Giraldus: the MS Chronicle of St Werburgh and by Henry Bradshaw a native of Chester and monk of St Werburgh's Abbey. In his "Life of St Werburgh" (1513), Bradshaw writes:

- "The year of grace six hundred fourescore and nyen As sheweth myne auctour a Bryton Giraldus Kynge Ethelred myndynge moost the blysse of Heven Edyfyed a Collage Churche notable and famous In the suburbs of Chester pleasaunt and beauteous In the honor of God and the Baptyst Saynt Johan With helpe of bysshop Wulfrice and good exortacion"

This rhyming legend has been copied and is still extant on a tablet which is suspended at the south west angle of the nave near the font. Although the copyist misread the word "exortacion" and spelled it "Excillion". In "The Medieval Architecture of Chester", John Henry Parker, writes that this was "a mistake into which others have subsequently fallen under the idea that the abbreviated word was the name of a person".

A problen with this source is that Bradshaw gives his source as "Giraldus" (Gerald of Wales), whereas the surviving Itinerarium Cambriae (1191) of Gerald's travels does not mention the founding of St John's at all. Leyland also refers to Gerald as his source, but whether this is a "cumulative error" or parts of Gerald's works have been lost is impossible to say.

Equally without support is the legend that Æthelred selected the site after a dream in which he was told to build a church where he saw a white hart. A stained glass window in the porch of the church shows the king with a white hart (there is a similar legend about David I of Scotland and "Holyrood Abbey"). It seems that Æthelred was a devout king, "more famed for his pious disposition than his skill in war". In 704, Æthelred abdicated to become a monk and abbot at Bardney, leaving the kingship to his nephew Cenred. There is much more on this period in the article Dark Ages.

The "Annals of Chester" give much the same facts about the origin:

- "In the year of our lord six hundred and eighty-nine Ethelred, king of the Mercians, the uncle of St Werburgh, with the assistance of Wilfric, bishop of Chester, as Giraldus [Cambrensis] relates, founded a collegiate church in the suburbs of Chester in honour of S. John the Baptist (Annals of Chester)"

Curiously, churches associates with white harts occur all along the River Dee. They are also generally associated with holy wells or springs. Examples include: Llandderfel (founded in the early 6th Century) and Llangar. Just downhill from St John's was Jacobs Well - now relocated to Grosvenor Park. Above the door of St John's is a much damaged statue of St Giles, together with his accompanying stag.

The story of the hind/stag also turns up in the Journal of the Archaeological Society (Vol 2):

- "Mr. J. H. Parker, F.S.A., read a paper “On St. John’s Church, Chester.” It appeared at, length in the Gentleman's Magjazine, 1858, pp. 273— 281. We will merely state here that Mr. Parker was of opinion that the present north-west tower, half detached as it stands, was completed in the time of Henry VII. or Henry VIII. In the west face of the tower there is a figure of St. Giles, abbot, in a niche of well-designed work, with his usual emblem, a stag, in his hand, to which the tradition of the white hind has been for centuries locally applied."

Despite what Parker seems to imply St Giles was not an abbot in Chester, but a one-time hermit, traditionally said to be from Athens whose legend is centered in Provence and Septimania. Giles founded the abbey in Saint-Gilles-du-Gard whose tomb became a place of pilgrimage. He is the patron saint of lepers from which St Giles Cemetery at Boughton presumably took its name.

Higden writing in the Polychronicon states that Wilfrid/Wilfric was the Bishop of Chester:

- "Wilfrid, having fled from Northumbria, succeeded at Legecestriam, which is now called Chester. However, within two years, on the death of Alfred, king of Northumbria, Wilfrid returned to his proper seat at Hexham"

From the above it is reasonable to assume that Chester had a bishop prior to the re-location of the north-west Mercian See from Lichfield to St John's Church by Peter of Lichfield in 1085. This is in agreement with the Chester Domesday which frequently refers to ‘the bishop’ or ‘the bishop of Chester’ as holding land or having rights in 1066. The Chester Domesday also gives a high status to St Peter in Chester as this is one of the very few times that Domesday refers to a church as "Templum". In addition Domesday also states that:

- "King Edward gave to King Gruffudd all the land that lay beyond the water which is called Dee. But after the same Gruffudd wronged him, he took this land from him and restored it to the Bishop of Chester and to all his men, who had formerly held it."

King Edward here is Edward the Confessor (king from 1042, died 5 January 1066) while King Gruffudd is Gruffydd ap Llywelyn (King of Gwynedd and Powys 1039–1055 and king of Wales 1055-1063), so Chester had a bishop some time before 1063. The "wronged" may be a reference to when Gruffydd allied himself with Ælfgar of Mercia, who had been outlawed for treason and the defeat of Ralph the Timid at Hereford in 1055.

So we have St Johns being possibly established around 689 - we must now consider what other dates can we establish for church activity at or near Chester? After the withdrawal of the Roman legions from their province of Britannia in 410, the inhabitants were left to defend themselves against the attacks of the Saxons. Before the Roman withdrawal, Britannia had been converted to Christianity and produced the ascetic Pelagius (c. AD 360 – 418). Britain sent three bishops to the Council of Arles in 314, and a Gaulish bishop went to the island in 396 to help settle disciplinary matters. Material remains testify to a growing presence of Christians, at least until around 360.

After the Roman legions departed, pagan tribes settled the southern parts of the island while western Britain, beyond the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, remained Christian. This native British Church developed in isolation from Rome under the influence of missionaries from Ireland and was centred on monasteries instead of bishoprics. Other distinguishing characteristics were its calculation of the date of Easter and the style of the tonsure haircut that clerics wore. Evidence for the survival of Christianity in the eastern part of Britain during this time includes the survival of the cult of Saint Alban and the occurrence in place names of "eccles", derived from the Latin ecclesia, meaning "church" (as in Eccleston). There is no evidence that these native Christians tried to convert the Anglo-Saxons. The invasions destroyed most remnants of Roman civilisation in the areas held by the Saxons and related tribes, including the economic and religious structures.

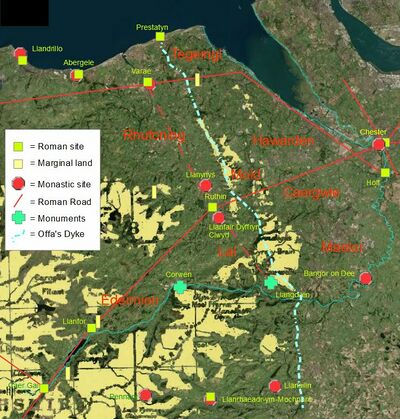

Bangor-on-Dee

The monastery of Bangor-on-Dee (see: "The vanishing monastery") was located some 13 miles upriver from Chester and despite its fabled vast extent comparatively little is known about it. It is often said that the monastery was established at Bangor in about AD 560 by Saint Dunod (or Dunawd) and was an important religious centre in the 5th and 6th centuries. Even these few facts are uncertain. Despite the monastery being described in terms which would make it the largest in Britain - more of a monastic city than a cluster of religious buildings - no remains have actually been identified, while from its size as described by some authors at least some would be expected. The sheer size is astonishing - a concentration of over 2,100 monks in any one Celtic mother church would be unique in Wales. The Welsh Triads go one better and specify 2,400 monks forming a "Perpetual Choir" at Bangor. Such numbers of people and densities are not to be encountered in Wrexham Maelor until the latter half of the eighteenth century when the Industrial Revolution was well under way. While most versions of the story have the abbey established around 560, some stories, such as those recorded by Samuel Lewis, imply a much earlier date:

- "It was the site of the most ancient monastery in Britain, which having also been intended as a school for religious instruction, became a great seminary for learning. From this institution, the foundation of which is ascribed by some to Lucius, King of Britain, under whose auspices Christianity is said to have been firmly established in this country, the place obtained its British name Ban-Gôr, which was changed by the Saxons into Banchornabyrig, a name descriptive of its importance as a privileged town. Pelagius, the noted arch-heretic, who is affirmed to have been a native of Britain, was educated at this monastery, of which he became abbot, about the commencement of the fifth century. The Pelagian heresy was principally eradicated by St. Germanus, who is said to have introduced considerable improvement into the institution."

If, as Lewis states, Pelagius (c. 360-418) was educated at Bangor-on-Dee, then the monastery must have been in existence well before 380, when Pelagius moved to Rome, and therefore would have existed under Roman rule in Britain. Late Roman and sub-Roman christian churches are known in the Dee valley (such as at Eccleston), but Lewis canot be correct when he says that Pelagius became abbot around 400 as he was in Rome at the time (having left Britain in around 380) and never returned to Britain.

As noted above, the exact location of the monastery is unknown and it may well be that the meandering of the Dee has wiped all trace of the site from the face of the land. The movements of the River are mentioned by John Leland (1506-52), Library Keeper to Henry VIII and later 'King's Antiquary' who visited Bangor in about 1539. Leland had read the standard 'historiographies' and monastic chronicles which account for a 'hearsay' element in his narrative, but also has pertinent things to say about the local topography, in particular providing evidence to the shifting within his lifetime of the course of the River Dee:

- "This is Bangor where the great abbey was. A part of this parish, that is as much as lies beyond Dee' on the north side, is in Welsh Maelor, and that is as half the parish of Bangor. But the abbey stood in English Maelor on the hither and south side of Dee. And it is ploughed ground now where the abbey was by the space of a good Welsh mile, and yet they plough up bones of the monks and in remembrance were dug up pieces of their clothes in sepulchres. The abbey stood in a Fair valley and Dee ran by it. The compass of it was as a walled town, and yet remains the name of the gate called Porthwgan by north and the name of another called Port Clays [Porth Klais] by south. Dee since changing the bottom runs now through the middle between the two gates, one being a mile and a half from the other, and in this ground be ploughed up foundations of squared stones, and Roman money is found there."

The Battle of Chester

The Welsh "Annales Cambriae" record a synod at Chester in 601. Possibly this was related to the mission of Augustine. There were deep differences between Augustine and the British church relating to the tonsure, the observance of Easter, and practical and deep-rooted differences in approach to asceticism, missionary endeavours, and how the church itself was organised. Some historians believe that Augustine had no real understanding of the history and traditions of the British church, damaging his relations with their bishops. Also, there were political dimensions involved, as Augustine's efforts were sponsored by the Kentish king, and at this period the Wessex and Mercian kingdoms were expanding to the west, into areas held by the Britons. The strife which followed near Chester involved a significant religious element.

Around 616 was the Battle of Chester: Æthelfrith of Northumbria against Kings Selyf Sarffgadau of Powys and Cetula (possibly Cadwal Crysban of Rhôs) and possibly also Iago ap Beli - possibly at Heronbridge. The Battle of Bangor-is-Coed follows in quick succession. Bede (writing in the 8th Century) provides the following information on the Battle of Chester: