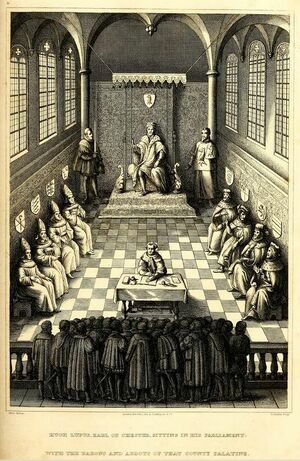

Chester Castle

Introduction

There are many ways to explore the history of Chester and it's connection to the broader sweep of more general history. With books, and better organised museums it is sometimes possible to start at a "beginning" and work through to an "end". In Chester an alternative is to walk around the City Walls, where different aspects of the history of the city are exposed in an almost random order. For the most adventurous a journey down the River Dee from source to sea provides another perspective. This article is a discussion of history based around the castle at Chester, but there are many branches into other threads of the local history.

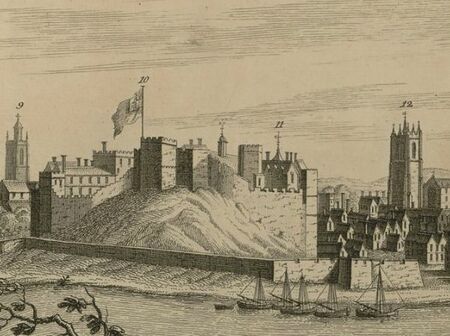

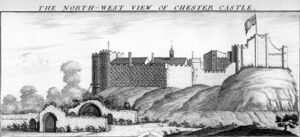

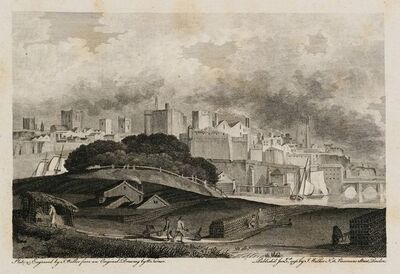

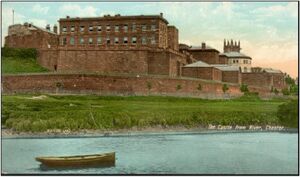

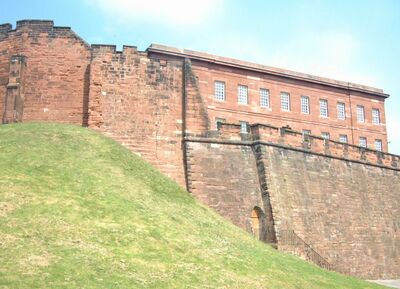

- "Neere unto the river standeth the Castle upon a rockie hill, built by the Earles, where the Courts Palatine and the Assises, as they call them, are kept twice a yeere." (William Camden: 2 May 1551 – 9 November 1623)

The Castle Timeline is on another page.

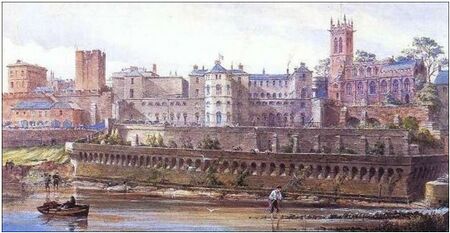

Chester Castle is one of the few castles in England or Wales that has been in constant use since first erected. For almost 2,000 years - even before the castle was built, armies have used and fought over this location. At times it has housed a mint, a prison, courts and local government offices. The Roman fortress, Æthelflæd's (Alfred the Great's daughter) burh, the small earthwork and timber castle of the Normans, and the larger stone castle created by Ranulf de Blondeville and Henry III were successively built near to, if not directly upon one another.

The history of the city and that of the castle are entangled. Indeed, the name of the city of Chester means simply "castle" and was used almost interchangeably in mediaeval descriptions such as the following of Hadrian's Wall:

- It had many towres or fortresses about a mile distant from another, which they call Castle steeds, and more with in little fensed townes tearmed in these daies Chesters, the plots or ground workes whereof are to be seene in some places foure square; also turrets standing betweene these, wherein souldiers being placed might discover the enimies and be ready to set upon them, wherein also the Areani might have their Stations, whom the foresaid Theodosius, after they were convicted of falshood, displaced and removed from their Stations.

Any castle, an particularly this castle is more than its stones, and the different layers of history can take some time to disentangle. If you visit, don't expect a grand ruin of a castle like Conwy. The surviving parts of Chester castle are impressive, but Chester Castle is more to do with social history than being a frozen ruin of a bygone age. Over the years:

- the castle has seen revolts (several successful, several not) against various English rulers;

- has been besieged (but never itself taken by siege), has been a prison of kings and princes or of those who revolted against them - a few of whom escaped;

- has seen trials of the unquestionably guilty (and of the probably innocent);

- has been amongst the best (or the worst) prisons in the country;

- has been involved in the success and failure of many military campaigns.

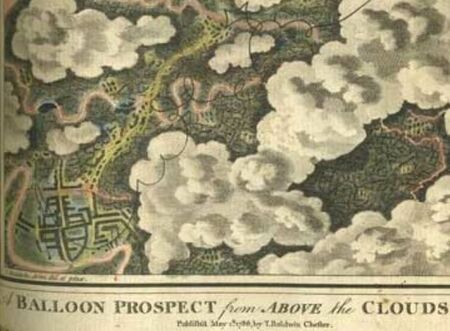

Through almost all of history, someone has been trying to get inside or outside of the walls of the Castle at Chester - the Earl of Derby used a rope to get out (briefly), Reverend Baldwin used a hydrogen balloon.

Conflict and Fortification at Chester (Prehistoric to 1069)

During the times of the Romans, the wars of the Welsh and Northumbrians, the English and the Danes and indeed later during the Civil War, Chester has found itself at an often fought-for crossroads. Until shortly after the Norman Conquest, the fortifications in and around Chester were probably not at the site of the present castle, but there were still defensive works here. The fortuitous combination of a bend in the navigable River Dee around high ground, the lowest ford on that river, and nearby springs to provide a water supply meant that this was an ideal location for a Roman fortress-city, an Anglo-Saxon fortified "burg" and later a Norman castle.

One interesting theory about the importance of Chester (and one possible reason why there was so much fighting here) is that it may mark the meeting point of several major European human genetic groups. One theory holds that after the last ice age the Celts migrated back up the Atlantic coast from their ice age "refuge" in Spain. These coastal people became the Cornish, the Irish and the Welsh. Other groups repopulated the British Isles through Norway and other parts of Scandinavia and a third group migrated across the land bridge that then connected Britain with Europe across what is now the channel. Where these people live today can be mapped using genetic studies. Chester turns out to be a possible "outpost" of the "English" genes. According to the Oppenheimer Theory these are much earlier movements of people than the supposed invasions of the red-haired "Vikings", the blonde "Angles" and "Saxons" or the brunet "Celts". However the conflicting theories about who moved where and when are still the subject of much debate! If this theory holds water, then Chester is placed at (or close to) the "triple point" where the worlds of the "Iberian/Celtic", "Scandinavian" and "Anglo-Saxon/Germanic" peoples collide and is one of the few points where the Anglo-Saxon group would have an "Atlantic" port and access to participation in the "Irish Sea Culture". Chester's history is in part the history of that port and its decline through the silting of the River Dee. More on the history of the port can be found under Portpool and there is a detailed article on Chester and Ireland.

An Iron Age Fortress?

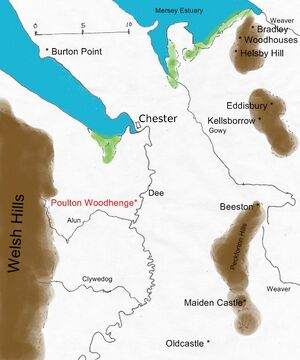

There is no definitive evidence for any kind of Iron Age fortification at Chester itself, but signs of Iron Age settlement (including post-holes) have been found in Chester and reported. It is likely that such a settlement would have included some kind of defensive structure. Hill top enclosures are known along the Sandstone Ridge which runs down the center of Cheshire at nearby Beeston, Bickerton and Kelsall. Earthworks have also been found at Heronbridge, a little south of Chester (although likely much later). The forts form two geographical groups of three, with Maiden Castle (Bickerton) on its own in the south of the county; Eddisbury hill fort is in the southern group with Kelsborrow Castle and Oakmere hill fort. Helsby Hillfort, Bradley and Woodhouses, form the Northern group.

Some early historical speculation is found in Samuel Lewis's 1848 Topographical Dictionary of England which includes the following information for Chester:

- The origin of this ancient city has been ascribed to the Cornavii, a British tribe who, at the time of the Roman invasion, inhabited that part of the island which now includes the counties of Chester, Salop, Stafford, Warwick, and Worcester; and its British name Caer Leon Vawr, "city of Leon the Great," has been referred to Leon, son of Brût Darian Là, eighth king of Britain.

There may be some confusion here with Caerleon in south Wales. Caerleon is also a site of considerable archaeological importance, with a Roman legionary fortress (it was the headquarters for Legio II Augusta from about AD 75 to 300) and an Iron Age hill fort. The name Caerleon is derived from the Welsh for "fortress of the legion" (compare with the Anglo-Saxon name for Chester - Legercyestre). "Brût Darian Là" (Welsh: Bryttys darian las) appears to be a reference to Brutus Greenshield one of the legendary kings mentioned by the notoriously inaccurate Geoffrey of Monmouth's 1136 pseudohistorical (i.e. mostly "made up") Historia Regum Britanniae ("the History of the Kings of Britain"). The "Leon" in question may be Liel after whom Carlisle (another Roman fort) may or may not be named.

Raphael Holinshead (writing in the 1570's) tells a similar story, including mention of a specific governor of Britain, Publius Ostorius Scapula (who was governor of Britain from AD47-52):

- Carleil builded. Chester repaired. Leill the sonne of Brute Greeneshield, began to reigne in the yeare of the world 3021, the same time that Asa was reigning in Iuda, and Ambri in Israell. He built the citie now called Carleil, which then after his owne name was called Caerleil, that is, Leill his citie, or the citie of Leill. He repaired also (as Henrie Bradshaw saith) the citie of Caerleon now called Chester, which (as in the same Bradshaw appeareth) was built before Brutus entrie into this land by a giant named Leon Gauer. But what authoritie he had to auouch this, it may be doubted, for Ranulfe Higden in his woorke intituled "Polychronicon," saith in plaine wordes, that it is vnknowen who was the first founder of Chester, but that it tooke the name of the soiourning there of some Romaine legions, by whome also it is not vnlike that it might be first built by P. Ostorius Scapula, who as we find, after he had subdued Caratacus king of the Ordouices that inhabited the countries now called Lancashire, Cheshire, and Salopshire, built in those parts, and among the Silures, certeine places of defense, for the better harbrough of his men of warre, and kéeping downe of such Britaines as were still readie to moue rebellion.

Ptolemy's 2nd century Geographia has a passing mention (text) of the two cities of the Cornovii as:

- .From these toward the east are the Cornavi, among whom are the towns: Deva, Legio XX Victrix 17°30 56°45 and Viroconium 16°45 55°45

"Deva Victrix" is Chester (see Roman Chester), and "Viroconium" is Wroxeter. The later had become the capital of the Cornovii under Roman rule.

While the evidence is scant, mixed-in with a lot of myth, at times confusing and some of the sources are known to be rather suspect, it may well be that there was some form of fortification at Chester in the Iron Age, but nothing is known of any particular part which it might have played in history.

The Roman Fort - Romani Ite Domum

Raphael Holinshead (writing in the 1570's) gets the story a a little confused and has the Romans responsible for the undercrofts on The Rows:

- There be some led by coniecture grounded vpon good aduised considerations, that suppose this Ostorius Scapula began to build the citie of Chester after the ouerthrow of Caratacus: for in those parties he fortified sundrie holds, and placed a number of old souldiers either there in that selfe place, or in some other néere therevnto by waie of a colonie. And for somuch (saie they) as we read of none other of anie name thereabouts, it is to be thought that he planted the same in Chester, where his successors did afterwards vse to harbour their legions for the winter season, and in time of rest from iournies which they haue to make against their common enimies. In déed it is a common opinion among the people there vnto this daie, that the Romans built those vaults or tauerns (which in that citie are vnder the ground) with some part of the castell. And verelie as Ranulfe Higden saith, a man that shall view and well consider those buildings, maie thinke the same to be the woorke of Romans rather than of anie other people. That the Romane legions did make their abode there, no man séene in antiquities can doubt thereof, for the ancient name Caer leon ardour deuy, that is, The citie of legions vpon the water of Dée, proueth it sufficientlie enough.

Sometime around AD74, the then governor of Roman Britain, Sextus Julius Frontinus constructed an "auxiliary fort" at Deva Victrix (Chester). The placement of this fort (at the lowest ford of the River Dee) appears to have been a strategic move by Frontinus with the intent of both blocking the route of any routed British trying to escape to the north, and to guard against help arriving from the Brigantes and other northern tribes. Frontinus was a noted engineer as well as being a governor, and author of De aquis urbis Romae, a history and description of the water supply of Rome. It is not known whether he was involved in providing Chester's water supply from the springs at Boughton to the Roman fort, but is is known that at this time lead (such as is used for plumbing) was traded with the Deceangli of north Wales. The lead was probably mined at Pentre.

- In June 1885 (at the Roodee) a lead 'pig' was found inscribed IMP•VESP•AVGV•T•IMP•III: the word DECEANGI appears on the side (this has been dated: AD74).

- In 1838 (1¼ miles east of Chester's Eastgate) another 'pig' was found with the inscription; IMP•VESP•V•T•IMP•III•COS, and again, on the side; DECEANGI (again dated: AD74).

Agricola

Frontius was succeeded as governor (in AD78) by Gnaeus Julius Agricola a Roman general responsible for much of the Roman conquest of Britain. His biography, the well known "De vita et moribus Iulii Agricolae" (The Life and Character of Julius Agricola), was the first published work of his son-in-law, the historian Tacitus (and says nothing at all about Chester). By AD79, the fort had developed into the extensive base of Legio II Adiutrix Pia Fidelis. There is another naval link here as the Second Legion were initially raised by Vespasian from the marines (Classis Ravennatis)of the Adriatic fleet. There is no real agreement on the size of the roman fleet which might have been associated with Chester - however it may have been the embarkation point for an attempted invasion of Ireland. There is also no real agreement about what is often called the "massive Roman harbour" and pictured to be the size of the modern Roodee.

Further lead piping can be seen in the Grosvenor Museum which bears the name of Gnaeus Julius Agricola in the following form:

- IMP•VESP•VIIII•T•IMP•VII•COS•CN•IVLIO•AGRICOLA•LEG•AVG•PR•PR

- (Imperator Vespasian nine times and Imperator Titus seven times consul. For Gnaeus Julius Agricola, pro-praetorian legate of the emperor)

Reconstructions of Roman Chester have no specific fortification on the site of the present castle, and the city walls were only extended in mediaeval times to enclose the current castle site. During the Roman period, the Castle site was close to an extra-mural official inn or "mancio" forming part of the "Cursus Publicus" (the first pub in Chester?) - although this could also have been the site of a mansion. Quite why the "Agricola Tower" at the Castle is named after the governor is something of a mystery, and over the years it has also been referred to as "Julius Caesar's Tower".

The Romans stayed in Chester until about 369, when Legio XX Valeria Victrix was withdrawn as part of the general collapse of Roman Britain and in the face of increasing "barbarian" attacks. There is no evidence that during the Roman occupation the fortifications of Roman Chester were ever put to the test.

The Grosvenor Museum contains a skeleton recovered from the bottom of a Roman well near the site of the Castle. Whoever it was, they had broken their leg earlier in life and it had been badly set, so they would have walked with a limp. It appears that the well was near the site of a fire which happened at around the time that the body ended up in the well.

King Alfred and "Chester Castle"

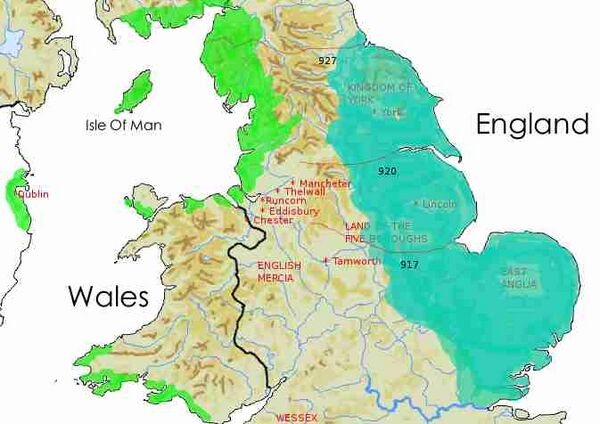

Around 893, in the time of Alfred, the Danes crossed to England. After a complex campaign the Danes made a forced march across England to occupy the ruined Roman fortress of Chester, arriving late in the year. The Wirral had strong Viking connections after 902 and there may already have been some link ten years earlier.

The Chronicle of John Brompton, seems to be the first work to mistakenly have the castle in existence prior to the Norman Earls of Chester. This error was copied by many later authors. The Victorian work "Picturesque England" describes the fortifications at Chester of Alfred's time of being a round sandstone castle:

- The Danes, the following and more terrible invaders, who had been allowed by Alfred the Great to settle in Northumberland, next assailed Chester, and seized the fortress, which was circular and of red stone...

This may simply be an assumption on the part of the author that the present works are older than they actually are (his source is unknown). However a more interesting possibility is that the "fortress" was in fact the Roman Amphitheatre. If this was even partially intact at the time, it could have provided an excellent defensive position.

King Alfred did not attempt a winter blockade, but besieged the Danes for two days, while he drove away all the cattle; burned the corn thereabouts and slaughtered every Dane that dared venture outside the encampment. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells the story as:

- Þa hie on Eastseaxe comon to hiora geweorce. 7 to hiora scipum. þa gegaderade sio laf eft of Eastenglum, 7 of Norðhymbrum micelne here onforan winter 7 befæston hira wif, 7 hira scipu, 7 hira feoh on Eastenglum, 7 foron anstreces dæges 7 nihtes, þæt hie gedydon on anre westre ceastre on Wirhealum, seo is Legaceaster gehaten; Þa ne mehte seo fird hie na hindan offaran, ær hie wæron inne on þæm geweorce; Besæton þeah þæt geweorc utan sume twegen dagas, 7 genamon ceapes eall þæt þær buton wæs, 7 þa men ofslogon þe hie foran forridan mehton butan geweorce, 7 þæt corn eall forbærndon, 7 mid hira horsum fretton on ælcre efenehðe. 7 þæt wæs ymb twelf monað þæs þe hie ær hider ofer sæ comon. (As soon as they came into Essex to their fortress, and to their ships, then gathered the remnant again in East-Anglia and from the Northumbrians a great force before winter, and having committed their wives and their ships and their booty to the East-Angles, they marched on the stretch by day and night, till they arrived at a western city in Wirral that is called Chester. There the army could not overtake them ere they arrived within the ramparts: they besieged the ramparts though, without, some two days, took all the cattle that was thereabout, slew the men whom they could overtake outside the ramparts, and all the corn they either burned or consumed with their horses every evening. That was about a twelvemonth since they first came hither over sea.)

Early in 894 (or 895), want of food obliged the Danes to retire once more to Essex (after a few raids on Wales). It is not clear what the inhabitants of Chester (if there were any at the time) thought of this wanton destruction.

Æthelflæd

The Roman city was refortified around 907 by the Mercians. The event is recorded in the Chronicle (although versions vary) and a cryptic note from 907 that "Chester was restored" suggests more fighting in that year :

- A.D. 907. This year died Alfred, who was governor of Bath. The same year was concluded the peace at Hitchingford, as King Edward decreed, both with the Danes of East-Anglia, and those of Northumberland; and Chester was rebuilt.

Raphael Holinshead (writing in the 1570's) also mentions the same, adding that this was when the walls were extended by Æthelflæd - daughter of Alfred and sister to the King:

- Not without good reason did king Edward permit vnto his sister Elfleda the gouernment of Mercia, during hir life time: for by hir wise and politike order vsed in all hir dooings, he was greatlie furthered & assisted; but speciallie in reparing and building of townes & castels, wherein she shewed hir noble magnificence, in so much that during hir government, which continued about eight yéeres, it is recorded by writers, that she did build and repare these Tamwoorth was by hir repared, Eadsburie and Warwike towns, whose names here insue: Tamwoorth beside Lichfield, Stafford, Warwike, Shrewsburie, Watersburie or Weddesburie, Elilsburie or rather Eadsburie, in the forrest of De la mere besides Chester, Brimsburie bridge vpon Seuerne, Rouncorne at the mouth of the riuer Mercia with other. Moreouer, by hir helpe the citie of Chester, which by Danes had beene greatlie defaced, was newlie repared, fortified with walls and turrets, and greatlie inlarged. So that the castell which stood without the walls before that time, was now brought within compasse of the new wall.

Holinshead's view also raises the question as to whether there was a "Castle" at Chester prior to the construction of the Norman motte at around the time of Hugh of Avranches, i.e. after 1070. If Holinshead was correct, this would have been an Anglo-Saxon castle and the view of many historians is that the only castles in England prior to the Norman Conquest were a handful of which some were built by Norman nobles who had been favourites of king Edward the Confessor. These include Richard's Castle, Hereford Castle, Ewyas Harold Castle and Clavering Castle. This does not fit with the situation in Chester, where there is no evidence for any Norman presence prior to the Conquest. There were some Anglo Saxon "castles" which were the remains of Roman Forts, one example being Portchester. These were not large legionary fortresses, such as Chester, but much smaller structures which could be supported with much smaller resources. Holinshead is probably mistaken due to his familiarity with later castles.

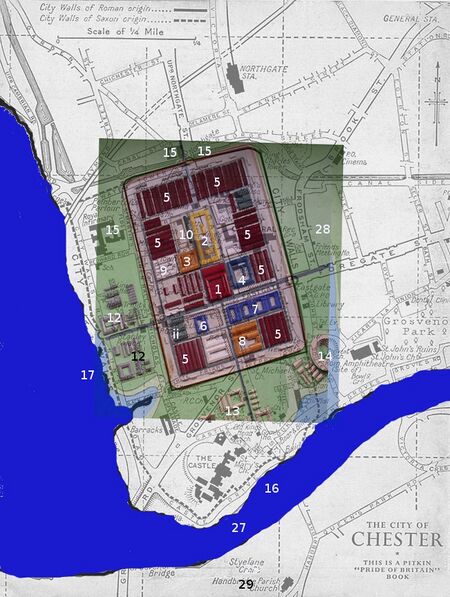

In the original Roman plan the City Walls followed their current route around the north and east of the city from St Martins Way to Pepper Street. However the western boundary of the walls followed St Martins Way south to around Whitefriars and then turned east to close the circuit close to the Amphitheatre. Holinshead is correct in that the site of Chester Castle was not enclosed within the Roman walls. The extension of the walls was from the north-west corner fort towards the later site of the Watertower and from the south-east corner fort towards the River Dee. Potential evidence that the walls were complete by the time of Edward the Elder (899-924) exists in the form of a coin type apparently minted at Chester early in his reign, the reverse of which has been interpreted as either a building, in the form of a church tower or the gateway to a burh or as a reliquary box containing the remains of an otherwise unknown saint.

The Saxons seemed to have preferred fortified manor-houses to the Norman Castles, as they were part of the society they were protecting rather than seeking protection from a conquered and occupied nation. There may have been some form of Saxon structure on the site of the castle, but the evidence for this is very slight. Generally, the mound on which the castle stands is said to have been constructed by the Normans, but archaeological evidence from the Mansio well shows the presence of bedrock at a very shallow depth and available information from boreholes in the vicinity suggests that the castle site may once have been occupied by a natural rocky outcrop. A woodcut said to be from 1884 places "Æthelflæd's Mound" at the location of the castle, but the woodcut is of unknown provenance and has several unhistoric features: such as the course of the Dee, location of St Bridget, Grosvenor Street and the line of the walls as adapted for the Georgian Jail.

Holinshead may be just plain wrong about the actual Castle itself being brought "within compasse of the new wall" - on the grounds that it was not actually built at the time. However it is just possible that the "castle" referred to (and possibly the place the Vikings used as a stronghold) was the re-used ruin of one of the substantial Roman buildings outside of the line of the Roman walls - for example the "Mansio" (marked "13" on the map above) or one of the other "circular" buildings around a square courtyard. However, the most likely candidate for the early "castle" remains the Amphitheatre.

Henry of Huntingdon, (sometimes not a reliable source) wrote of Æthelflæd:

- "Some have thought and said that if she had not been suddenly snatched away by death, she would have surpassed the most valiant of men."

This has led to the speculation that if Æthelflæd had not died in June 918 (probably aged 40-50), but had outlived her brother Edward the Elder (who died at Farndon, near Chester, in 924) then she might soon have become "Queen of All England" at Eamont Bridge as the unification of England could have taken place, not under King Æthelstan in 927, but under Æthelflæd.

Sources & links

The Chester Castle Site (Middle Ages)

During the 10th century Chester became well established as a major Mercian port and appears to have been the only sizable port in the region. From the 990s the family of Leofwine of Mercia settled in Chester and helped to ensure the city's survival as a major provincial centre. Leofwine was an "Ealdorman". Towards the end of the tenth century, the term ealdorman gradually disappeared as it gave way to eorl, probably under the influence of the Danish term jarl, which evolved into modern English earl. The analogous term is sometimes count, from the French comte, derived from the Latin comes. The ealdormen can be thought of as the early English earls, for their ealdormanries (singular ealdormanry, same meaning as earldom) eventually became the great earldoms of Anglo-Danish and Anglo-Norman England. By 1066 Chester was a prosperous town with a population of between 2,500 and 3,000, producing annual taxes of £45 (this was pounds of silver in 1066 money: see Saxon Pound) and 120 pine marten pelts, together with an additional income from the mint - see Dark Ages. Chester was assessed as including the townships of Handbridge, Newton by Chester, 'Lee' (Overleigh and Netherleigh), and 'Redcliff'. Already, Chester had its own laws and customs, administered by the "hundredal court", over which presided 12 doomsmen (iudices civitatis) drawn from the men of king, earl, and bishop, and liable to fines payable to the king and earl for failure to carry out their duties. The "doomsmen" have been regarded as evidence of Scandinavian influence on Chester's institutions and have been compared to the 'lawmen' (lagemen or iudices) of some boroughs in the Danelaw.

There is no firm evidence that the family of Leofwine, including Leofric, Ælfgar, Edwin and Morcar had a castle at Chester. The pre-Norman Burghal defences appear to have been intended to protect the community as a whole from a potential "foreign" invader, be that Viking or Welsh, rather than to assist a local ruler or dynasty in maintaining hegemony over the local or wider populace. The size of a burh was designed to house an entire community on a permanent basis. Within the burh the first stone buildings may well have been those for broad community use, such as churches. High status Saxon leaders would have had manor houses and halls, originally built in wood with only a few later rebuilt in stone. Few examples of Anglo Saxon architecture survive.

William the Bastard and Hugh the Fat

Chester played some part in the events following Hastings:

- Immediatlie after he [William] had thus got the victorie in a pight field (as before ye haue heard) he first returned to Hastings, and after set forward towards London, wasted the countries of Sussex, Kent, Hamshire, Southerie, Middlesex, and Herefordshire, burning the townes, and sleaing the people, till he came to Beorcham. In the meane time, immediatlie after the discomfiture in Sussex, the two earles of Northumberland and Mercia, Edwin and Marchar, who had withdrawne themselues from the battell togither with their people, came to London, and with all speed sent their sister quéene Aldgitha vnto the citie of Chester, and herewith sought to persuade the Londoners to aduance one of them to the kingdome: as Wil. Mal. writeth. (Holinshed)

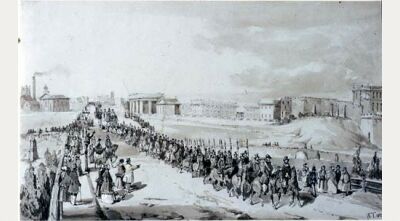

Chester was one of the last places subdued after the Norman Conquest. During the "Harrying of the North" (1069-1070), the death toll is believed to have been 150,000, with substantial social, cultural, and economic damage. Due to the ruthless and violent "scorched earth" policy which the Normans employed, much of the land was laid waste and depopulated. In parts of the north, the damage was such that the survivors had to resort to cannibalism. Inevitably, plague followed. All told, about a fifth of the population of England may have died during the Norman Conquest.

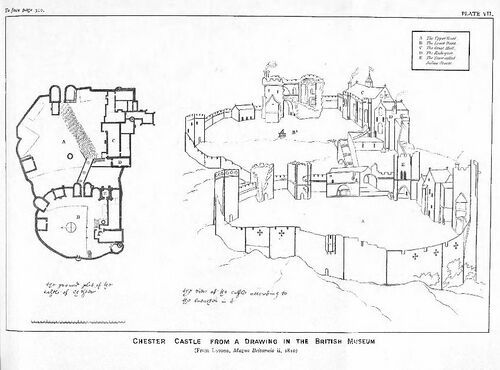

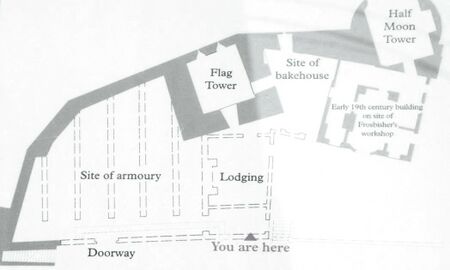

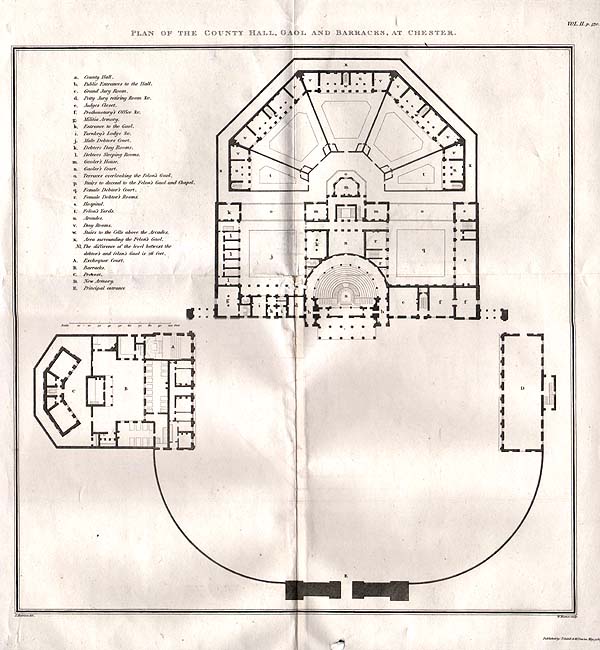

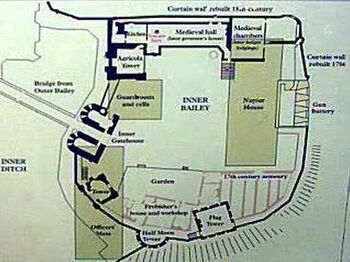

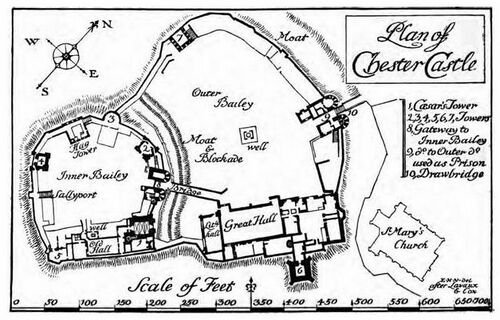

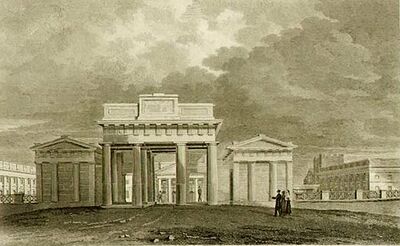

In 1069 the men of Chester in alliance with "Eadric the Wild" and the Welsh rose against the Conqueror and laid siege to Shrewsbury. William quelled the revolt and ordered a castle to be built at Chester in 1069-1070. A large "motte and bailey" castle was constructed overlooking the lowest fording point of the River Dee. In order to make space for this, or perhaps as part of the "harrying", half the Saxon city was leveled. The ramparts and tower at this time would have been wooden. Very roughly, the motte or "inner ward" occupied the present site of the older buildings on the hill that can still be seen, while the bailey or "outer ward" occupied the site of the present car-park between the pillared entrance and include the site of the more modern buildings. The central keep of the castle is believed to have been located on the site of the surviving "Flag Tower", shown in the map below.

As can be seen from the satellite image the motte at Chester is unusual in that it is oval rather than round. The presence of the mound comprising the motte has been confirmed by excavation conducted by Peter Hough in 1982, and in 1995 archaeologists discovered some re-deposited Roman remains which appear to have been up-cast from the Castle ditch during the construction of the motte. However, very little documentation survives from this time, with the exception of the minorities of Hugh de Kevelioc (1153-81) and Ranulf de Blondeville (1181-1232) when the Castle came into the hands of the king. During these minorities a sum of £102. 7s. 6d was spent on the Castle, and a further £20 on the castle bridge. The location of this bridge may have then been in front of the building known as the Agricola Tower, thought to be of late 12th century construction, as the original gateway to the Inner Bailey.

A description of this type of castle is given in the life of St John, Bishop of Terouanne:

- "The rich and the noble of that region being much given to feuds and bloodshed, fortify themselves ... and by these strongholds subdue their equals and oppress their inferiors. They heap up a mound as high as they are able, and dig round it as broad a ditch as they can ... Round the summit of the mound they construct a palisade of timber to act as a wall. Inside the palisade they erect a house, or rather a citadel, which looks down on the whole neighbourhood".

This is the first real evidence of actual fortification exactly on the present site of Chester Castle.

At first, Chester was held by Gherbod the Fleming but when he returned to "more civilised" Normandy the castle and surrounding districts were given (1071) by the King to Hugh of Avranches. A footnote in Gerald of Wales tells it thus:

- The first earl of Chester after the Norman conquest, was Gherbod, a Fleming, who, having obtained leave from king William to go into Flanders for the purpose of arranging some family concerns, was taken and detained a prisoner by his enemies; upon which the conqueror bestowed the earldom of Chester on Hugh de Abrincis or of Avranches, "to hold as freely by the sword, as the king himself did England by the crown."

Hugh of Avranches had contributed to William's invasion of England (providing 60 ships). He did not fight at Senlac Hill (called Hastings by some), but was trusted to stay behind and govern Normandy. Hugh was born around 1047, and so would have been in his early-20's when he gained Chester.

By 1075 and the subjugation of the Revolt of the Earls, the Conquest was completed. Before his death in 1101, Hugh went on to make a huge fortune from his position as the Earl of Chester and also became so fat that he could hardly walk (he was known in later life as "Hugh the Fat"). A further castle was build at Frodsham although nothing of this now remains - Frodsham Hill was the location of an Iron Age promontory fort, the outline of which can still be seen.

As later events were to show, The Earls of Chester may have had a solid castle, but they tended to lead tumultuous lives.

The Nineteen Year Winter

The line of the d'Avranches as Earls of Chester failed when Hugh of Avranches's son Richard of Avranches, with his illegitimate half-brother Ottuel, joined the young prince William (heir to Henry I) aboard the doomed White Ship in 1120. The ship foundered, drowning all but one, and Richard of Avranches died aged 26, leaving no issue. The disaster was the "Titanic" of its day - a much praised vessel at the forefront of technology, on its maiden voyage, wrecked against a foreseeable natural hazard in the reckless pursuit of speed suggested by an influential passenger, while sailing in the moonless dark.

William of Malmesbury wrote, in his Chronicle of the kings of England:

- "Here also perished with William, Richard, another of the King's [Henry I] sons, whom a woman of no rank had borne him, before his accession, a brave youth, and dear to his father from his obedience; Richard d'Avranches, second Earl of Chester, and his brother Otheur; Geoffrey Ridel; Walter of Everci; Geoffrey, archdeacon of Hereford; [Matilda] the Countess of Perche, the king's daughter; the Countess of Chester; the king's niece Lucia-Mahaut of Blois; and many others..."

The earldom then passed through his father Richard of Avranches's sister Maud to Richard of Avranches's first cousin Ranulf de Meschines, in 1121. However, following the death of Henry I, the loss of the White Ship was a cause of the conflicting claims to the throne during the period of the Anarchy (1135–1154) during which:

- "æuric rice man his castles makede and agænes him heolden; and fylden þe land ful of castles. Hi suencten suyðe þe uurecce men of þe land mid castelweorces; þa þe castles uuaren maked, þa fylden hi mid deoules and yuele men. Þa namen hi þa men þe hi wendan ðat ani god hefden, bathe be nihtes and be dæies, carlmen and wimmen, and diden heom in prisun and pined heom efter gold and syluer untellendlice pining; for ne uuaeren naeure nan martyrs swa pined alse hi waeron." ("Every chieftain made castles and held them against the king; and they filled the land full of castles. They viciously oppressed the poor men of the land with castle-building work; when the castles were made, then they filled the land with devils and evil men. Then they seized those who had any goods, both by night and day, working men and women, and threw them into prison and tortured them for gold and silver with uncountable tortures, for never was there a martyr so tortured as these men were.")

Ellis Peters set the Brother Cadfael stories (published 1977–1994) against the background of the Anarchy. During this time of trouble, known also as The Nineteen Year Winter, it was declared in the Chronicle that:

- "In the days of this King there was nothing but strife, evil, and robbery, for quickly the great men who were traitors rose against him. When the traitors saw that Stephen was a good-humoured, kindly, and easy-going man who inflicted no punishment, then they committed all manner of horrible crimes . . . And so it lasted for nineteen years while Stephen was King, till the land was all undone and darkened with such deeds, and men said openly that Christ and his angels slept".

The then Earl of Chester, supposed serial turncoat Ranulph De Gernon, played a major part in the fighting - both against the new king ( Stephen) and for him (he is said by some to have changed sides seven times). Henry I had not helped to ensure a simple succession as he still holds the record for the largest number of acknowledged illegitimate children born to any English king (around 20 or 25).

As the Chronicle puts it:

- After this waxed a very great war betwixt the king and Randolph, Earl of Chester; not because he did not give him all that he could ask him, as he did to all others; but ever the more he gave them, the worse they were to him.

Despite all this turmoil, no record exists of any fighting at Chester, and so the initial wooden Motte-and-Bailey was not put to the test.

Rebuilding in Stone

Hugh de Kevelioc, earl of Chester from 1153-1181, joined the baronial Revolt of 1173-1174 against Henry II, and lost the castle when captured and imprisoned. However, he had his estates restored in 1177. In 1159-60, £102 7s 5d was spent on work at the Castle and this may have included the construction of the Flag Tower on the site of the original Norman keep. The earliest deposits encountered by Archaology demonstrate that the medieval masonry defences in the western range of the Inner Bailey were built on top of the pre-existing Norman motte, evidenced by a layer of redeposited clay. An area of paving outside the eastern entrance to the Flag Tower lay directly above this clay and was thought to confirm the medieval origins of the Flag Tower’s entrance, associated with this was a single posthole. Sand and clay deposits were also found to overlie the redeposited clay and these produced pottery of 14thC date.

Hugh's son, Ranulf de Blondeville, otherwise known as Ranulph IV de Meschines (1172-1232) made an alliance with Llywelyn the Great (effectively Prince of Wales), whose daughter Elen ferch Llywelyn (the Elder) married de Blondeville's nephew and heir, John Canmore, in about 1222.

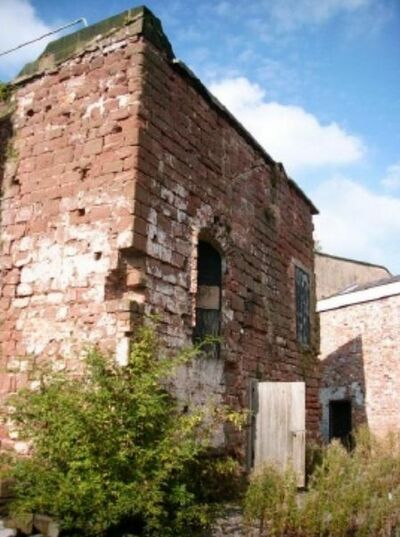

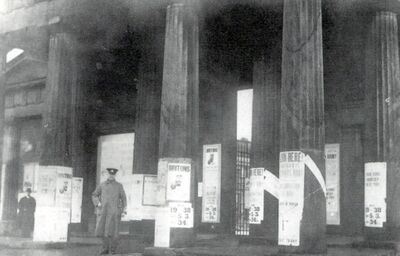

At around this time, the Agricola Tower was added to the castle. This is named after the Roman governor of the same name, but why is unclear. It was initially the inner gatehouse of the castle, but one end of the gate passage was later blocked up. John Henry Parker describes the castle of this period as follows:

- The Castle has been almost entirely rebuilt. The only remains of antiquity are a portion of the Norman walls of the substructure next the river, much patched, and the square tower called Julian's Tower. This was the gatehouse, built at the end of the twelfth century, during the period of the transition of styles. One side of it is built upon the Roman wall of the city, and one corner stands upon a Roman arch,—the vaulted passage through the tower remaining perfect, but walled up at both ends. Over it is a chapel, with a vault of transition Norman work, almost Early English, probably of about 1190 to 1200. The situation of the altar, with its piscina, credence, and locker, are plainly to be seen, though mutilated. There was a drawbridge from the outer entrance to the ancient wooden bridge which crossed the river at this spot, and there are remains of the causeway leading to it on the opposite side of the river.

The Tower is described at length in Samuel Lewis's 1848 Topographical Dictionary of England:

- Of the ancient castle, built by the Conqueror, there remains only a large square tower, called "Julius Agricola's Tower," now used as a magazine for gunpowder. Though of modern appearance, having been newly fronted, it is undoubtedly of great antiquity, and interesting as the probable place of confinement of the Earl of Derby, and the place in which Richard II., and Margaret, Countess of Richmond, were imprisoned. In the second chamber James II. heard mass, on his tour through this part of the kingdom, a short time previously to the Revolution. This apartment, when opened after many years of disuse as a chapel, exhibited, from the richness of its decorations, a splendid appearance, the walls being completely covered with paintings in fresco, as vivid and beautiful as when executed; and the roof, from the fine effect produced by the ribs of the groined arches, springing elegantly from slender pillars with capitals in a chaste and curious style, was equally striking.

While Margaret Countess of Richmond is mentioned as a prisoner by Lewis, it is improbable that she was. This is discussed in more detail below.

The Norman wooden tower at the summit of the motte was also replaced in the 13th century with a square stone tower, now known as the Flag Tower. Later castles had round towers so that there were no corners to attack with siege engines. Indeed, the later towers at Chester were round. The wooden palisade that ran around the summit of the motte was also later replaced with stone. When this was done, the wall was built flush with the flag tower (unlike in later castles where towers projected to allow fire along the walls). The lower level of the Flag Tower remains but is not visible from outside the castle, although it is possible to see where the stonework links up.

Ranulf de Blondeville (1172-1232) built, or improved, several other castles beside Chester. Much of his knowledge in this area may have come from the rapid improvements in castle design that occurred at the time of the crusades. Among Ranulf's other castles was Beeston, the "castle on the rock".

In 1191, Ranulf appointed William as the Mounter keeper of "my garden and my orchard at Chester", and William was also granted a "resting tree" and "residue of my apples after the shaking down of the trees of my garden".

The only surviving element of the castle attributable to the work of Ranulf de Blondeville is the Agricola Tower, which was probably intended to function as the gatehouse to the Bailey. The first floor seems to have been designed as a chapel from the outset, the capitals and vaulting of which are closely related to those in a chapel in the east transept of Chester abbey (now the Cathedral), and may even be by the same mason. Much of the remaining work that Ranulf may have been responsible for in the Inner Bailey may be conjectured from the early eighteenth century plans prepared by Lavaux and others. Historically it is known that on his return from the crusades in 1220, Ranulf embarked upon several castle building programmes at sites including Beeston and Bolingboke. Each of these castles were furnished with twin drum towered gatehouses and ‘D’ shaped mural towers, like the Half -Moon tower at Chester. In the case of Beeston castle it was sited on a crag, with a shear drop to its rear, very much like the site at Chester. Furthermore, the arrangement of the mural towers and gatehouse buildings at Beeston can be seen to have been influenced by the layout at Chester, on the north-eastern side of the Inner Bailey defensive circuit. It could be argued that Ranulf’s castles of the 1220’s were inspired by his experiences in Europe and the Holy Land, and involved state of the art castle building technology. There is little evidence to suggest that his defensive improvements of the Inner Bailey at Chester were ever substantially altered until mid 18thC. century and the time of Harrison, other than occasional periods of repair.

Henry III (King from 1216 to 1272) added (or completed) the part-round and projecting "Half-moon Tower" after the death of John Canmore without issue in 1237. He spent £1,717 on Chester Castle, a huge sum at the time. The defensive circuit of the Outer Bailey was almost certainly established by Henry III after 1237, but this would appear to have been an earth and timber rampart, probably hastily constructed to house troops and the royal entourage during successive campaigns in North Wales.

Some evidence relating to the walls of the castle of Chester was found in the Public Record-Office, London. The document proves that the date of the present walls cannot be earlier than the time of Henry III (1 October 1207 – 16 November 1272). While the document is not dated, it belongs to that reign; and from the handwriting, is probably about A.D. 1260.

Public Record-Qffice, London, Royal Letters, No. 437:

- "Henricus Dei gratia Rex Angliœ Dominus Hibermœ Dux Normanmse Aqnitaniœ et Comea Andegaviœ dilecto et fideli suo J. de Grey .Instil.hirió suo Cestrke. Mandamus vobis quod ballium circa castrnm nostrum Cestrise quod clausum lull palo, amoto palofflo, claudi faciatis calce et petra et similiter ballium circa castrum nostrum de Dissaid ubi necesse fuerit reparan faciatis. Et custum quod ad hoc posueritis per visum et testimonium legalium hominum computabitur vobis ad Scaccarium. Teste," [torn off]. ("Henry, etc .. To his beloved and faithful J. de Grey, his Justice of Chester. We command you that you cause to be removed the wooden fence of the bailey around our Castle of Chester, and that you cause the said bailey to be enclosed with a stone wall. And that in like manner you re-edify the bailey around our Castle of Dissaid, wherever it may be necessary. And the sums that you shall expend on the same being certified by the view and testimony of lawful men, shall be allowed to you at our exchequer." )

An important base for royal operations against the Welsh, the castle was visited by Henry III in 1241 before he overran north Wales, and again in 1245. The castle was used as a gaol as early as 1241, when Welsh hostages were confined there. In 1241 Henry III's first visit occasioned the construction of an 'oriel' before the doorway of the king's chapel, and in 1245 the king's apartments were repaired, the paintings in the queen's chamber were renewed, and a bridge was made from the castle into the orchard to enable the king and queen to take exercise. A series of major works in the later 1240s and early 1250s, marked the beginning of the removal of the principal apartments to the outer bailey. Between 1246 and 1248 a chamber over a cellar was erected at the considerable cost of nearly £220 and the wooden palisade of the outer bailey was replaced by a stone wall; in 1249 the hall in the outer bailey was demolished and a new one, which was to cost over £350, was begun. The high quality wall paintings in the Agricola Tower can possibly be attributed to Henry III’s improvements, especially considering his reputation as a patron of wall-painting at other royal residences, such as Winchester Castle in 1233 and Clarendon Palace in 1249 - but in both only fragments remain. From documentation pertaining to Henry III’s wall paintings and other imagery it is apparent that St. Edward was one of his favourite subjects, but that representations of the Virgin were the most commonly ordered subjects of all. This tallies well with the paintings at Chester Castle, making them the major surviving painting of Henry III’s almost obsessive patronage of this art. Moreover, a fragment on the east wall shows the head and shoulders of a figure wearing a straw hat and this might be St John, disguised as a beggar, an element in the story of St Edward and the Ring. This in turn might suggest that this wall cycle was devoted to St Edward, a saint for whom Henry III felt particular empathy.

Henry's son, the new Lord of Chester Castle (from 1254) and later Edward I, was an even more profligate castle-builder. According to some sources, a daring escape from Chester Castle was made in 1246 by Owain Goch ap Gruffydd, brother of Prince Llewelyn, who had been held hostage by King Henry - "Gwr ysydd yn nhwr yn hir westai" ("a man who is in the tower, long a guest") - although some claim he was imprisoned at Dolbadarn. Other sources have Henry III releasing Owain to cause trouble amongst his brothers. According to some sources Owain rejoined Llewelyn's forces and in 1257 they "ravaged the country to the very gates of the city" (others have him refusing to return to Wales). In response, King Henry and Prince Edward organised a further expedition into Wales, mustering men and equipment in the city. Envoys from Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd visited the king at Chester, and the royal wardrobe and its staff were again brought to the castle. After a fortnight's stay, Henry and Edward set out on what was to be Henry III's last invasion of Wales. They returned to Chester less than a month later after a brief campaign leading to a difficult peace.

The years 1264-5 brought the Second Barons' War to Chester, provoked ostensibly by Henry III's demands for extra finances, but which marked a more general dissatisfaction with Henry's methods of government on the part of the English barons, discontent which was exacerbated by widespread famine.

Samuel Lewis states:

- "Chester was captured by the Earl of Derby, in the year 1264, and held for the crown till the battle of Evesham, in which the barons were defeated with the loss of their leader, and an end put to the contest."

In fact while the City was captured the Castle was not. In 1265, during the Second Barons' War, the royalist supporters of Henry III, James of Audley and Urien of St. Pierre, besieged Luke de Taney, Simon de Montfort's justice of Chester, in Chester Castle for ten weeks. Taney surrendered upon news of de Montfort's defeat at Evesham, and Prince Edward himself occupied Chester, from where he sent out instructions described as his "first recorded act of state" as a "responsible adviser of the Crown", while not getting on with the Abbot and consuming his wine. The whole business is recorded in the Chester Chronicle as follows:

- "Dominus autem Eadwardus apud Herford die Jovis in Septimana Pentecostes de custodia Domini Simonis de monteforti evasit. Quo audito Jacobus de Audethlegio et V.de Sancto Petro, Sabbato sequenti castrum de Beuston nomine domini Edwardi ceperuntetdie Sancte Trinitatis Cestriam venientes de consilio civium, Lucam de Taney cum suis complicibus infra castrum Cestrie obsederunt per decem Septimanas continuas nec tamen illud obtinuerunt propter optimam inclusorum defencionem. Jacobus de Audethlegio factus est Justiciarius. Dominus vero Eadwardus interim associatis sibi Gilberto de Clare et aliis commarchionibus suis Simonem de Monte forti Henricum filium ejus Hugonem Disspenser, Petrum de Monte forti, Radulfum Basset et eorum complices sæpius [d]ebellavit et tandem eos apud Evsham ij. non. Maii in bello campestri prostravit: Winfridum de Bon, Henricum de Hasting, Guydonem de Monte forti in ipso bello captos apud castrum de D.(?) Beuston secum ducendo captivos. Audiens autem Lucas de Taney dominum Edwardum apud Beston venisse ij vigilias Asumpcionis castrum Cestrie reddidit eidem se suosque gratie sue subjiciendo. Quos idem Edwardus ad tempus incarceravit. Et postea paulatim et successive liberavit. Cumque dominus Edwardus multum irasceretur erga Simonem Abbatem Cestrie ingressum monasterii diucius precludens eidem, et multas intentans ei minas eoquod de licencia Domini Simonis de Monte forti et ipso inconsulto promotus esset tandem in primo ejusdem Abbatis adventu apud Beuston vigilia Asumpcionis contra spem multorum, dominus Edwardus divina inspiratione compunctus, ipsum Abbatem clementer admisit et de consilio domini Jacobi de Audithlegio tunc Justiciario Cestrie exitus monasterii adeo plene jussit eidem restitui, quod pro duobus doliis vini Abbatis tempore iracundiæ in familia ipsius domini Edwardi expensis: Alia duo dolia de Castro Cestrie extrahi et eidem reddi fecit Abbati." - But the lord Edward [the king's son] escaped from the custody of Simon de Montfort at Hereford on the Thursday [May 28] in Whit Week. When this was known James de Audley and Urian de Saint Pierre on the following Saturday seized the castle of Beeston in the name of the lord Edward, and coming to Chester on Trinity Sunday, they besieged Lucas de Taney and his accomplices in the castle of Chester for ten consecutive weeks, but did not succeed in taking it, on account of the excellent defence made by the besieged. James de Audley was made justiciary of Chester. In the meantime the lord Edward, Gilbert de Clare and others his fellow marchers being joined with him, made frequent attacks upon Simon de Montfort, Henry his son, Hugo Despencer, Peter de Montfort, Ralph Basset, and their accomplices, and at length completely overthrew them on the battlefield of Evesham on May 6. Humphrey de Bohun, Henry de Hastings, and Guy de Montfort, who were captured in this battle, Edward took with him as prisoners to Beeston castle. When Lucas de Taney heard that the lord Edward had come to Beeston, he surrendered the castle of Chester on the day before the eve of the Assumption [August 13], submitting himself and his companions to Edward's grace. For the time the same Edward imprisoned them, and afterwards gradually and successively liberated them. The lord Edward however was much enraged with Simon, abbot of Chester, for a long time refusing him access to the monastery, and holding out many threats to him, because he had been promoted by the licence of the lord Simon de Montfort, and without Edward having been consulted. At length, on the arrival of the same abbot at Beeston, on the vigil of the Assumption [August 14], the lord Edward contrary to the hope of many, but moved by divine inspiration, graciously admitted the said abbot, and by the advice of the lord James de Audley, then justiciary of Chester, commanded the revenues of the monastery to be so fully restored to him, that for two casks of wine consumed in the household of the said lord Edward, during the time of his anger against the abbot, he caused two other casks to be taken from the castle at Chester, and restored to the said abbot.

While de Montfort had held Chester Castle (see Earls of Chester), he had reached an arrangement with Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, something that Edward would neither forget nor forgive.

Sources & links

- Agricola Tower at English Heritage;

- Agricola Tower on Wikipedia;

The "Hammer Of The Scots"

Edward I (ruler from 1272 to 1307) is remembered as the conqueror of Wales and the "Hammer of the Scots" (he had this inscribed on his tombstone - "Edwardus Primus Scottorum Malleus hic est, 1308. Pactum Serva" - Here lies Edward 1st, hammer of the Scots. Keep the faith.). He also introduced to England the repugnant practice of forcing Jews to wear yellow patches on their outer garments - before their expulsion in 1290 (the idea was later copied by the Nazis). When the newly crowned Edward called Llywelyn ap Gruffydd, then Prince of Wales, to Chester Castle in 1275 to pay homage, Llywelyn refused to attend ("fearing for his safety") and Edward had the excuse he needed for the Welsh war. The event is reported as follows in the "Chester Chronicle":

- "Edwardus Rex Anglie in generali parlemento suo post coronacionem suam fecit multa statuta, decimas (fn. 1) regni obtinuit. Idem Rex apud Cestriam venit ut tractaret cum principe Wallie Lewelino et cito pro contemptu dicti principis recessit." - Edward, king of England, in his general parliament after his coronation, made many statutes and obtained [as a subsidy a grant of] a tenth [of the goods] of the kingdom. Also the king came to Chester, that he might treat with the prince of Wales, Llewelin, and soon returned on account of the contempt with which that prince [treated his invitation].

With the outbreak of Edward's first Welsh war in 1277, Chester Castle was made one of the three military commands from which Llywelyn's principality was attacked. Royal forces operating from the city under the command of William de Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, quickly brought northern Powys to submission. As in previous campaigns, workmen, soldiers, timber, ammunition, victuals and boats were assembled in the city. The royal wardrobe was also brought there in five carts. With the castle thus established as the chief base for operations in north-eastern Wales, Edward himself arrived July 1277 to lead a large force of infantry on the culminating campaign. He returned to the castle in September 1277 when it was clear that Llywelyn would be forced to surrender. As the Chronicle puts it:

- "Eadwardus Rex Anglie intravit Walliam cum comitibus et baronibus totius Anglie et obsedit eam undique tam per mare quam per terram unde capta fuit Angleseya tandem circa festum Sancti Martini in hieme Lewelinus princeps necessitate compulsus habito magnatorum consilio et beneficio absolutionis optento venit apud Rothelanum et ibi [se] subposuit omnino voluntati et misericordie domini regis." - Edward, king of England, entered Wales with the earls and barons of the whole of England, and besieged it on every side, as well by sea as by land, so that Anglesea was captured. At length about the feast of S. Martin [November 11] in winter, Llewelin, prince [of Wales], compelled by necessity, having taken counsel of the magnates and obtained the benefits of absolution, came to Rhuddlan, and there he submitted himself completely to the will and mercy of our lord the king.

After Llywelyn's defeat an unsteady compromise was reached, but strained relations did not last. After Llywelyn had been lured into a trap and put to death on 11 December 1282, his brother Dafydd became ruler of Wales.

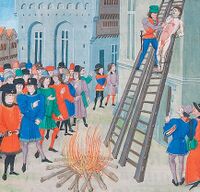

On 22 June 1283, Dafydd ap Gruffydd was captured. Dafydd, seriously wounded, was brought to Edward's camp at Rhuddlan and taken from there to Chester (presumably to the castle) and then on to Shrewsbury. On 30 September 1283, Dafydd was condemned to death, the first person known to have been tried and executed for what would be described as "high treason" against the king. The execution featured dragging through the streets, hanging, drawing and quartering, apparently at the express order and design of the vengeful Edward.

Under Edward I the royal accommodation was further improved and enlarged. Repairs were undertaken in 1275, and in 1276 the 'king's houses' in the outer bailey were renovated for the earl of Warwick and given a new chapel. In 1283 Edward I's visit necessitated further repairs to the hall and royal apartments, and to towers and domestic buildings in both wards. New domestic buildings were begun in 1284, and between then and 1291 over £1,400 was spent. The major works, started under the supervision of a Master William of Perton, included repairs to the king's houses, new chambers for the king and queen, and a stable, all probably in the outer bailey north and east of the great hall. Records exist of the purchase of "boards to make the alter of the chapel", and "glazing of the queen’s chapel". After the death of Master William the work was continued by Reginald de Grey, Justiciary of Chester, but the initial work was not of particularly high quality as by 1298-9 remedial works were needed to prevent the new buildings from falling down.

The future Edward II, was born in 1284, the fourth son of Edward I of England by his first wife Eleanor of Castile, and was the first English prince to hold the title of the Prince of Wales. He was also made Earl of Chester.

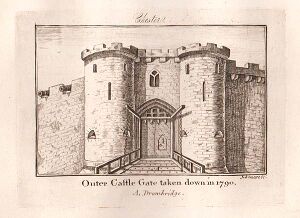

A new gateway tower to the outer bailey flanked by two half-round towers was added to Chester Castle c.1290, at a cost of over £318, between Edward's second and third Welsh wars. This eventually comprised twin drum towers, a vaulted passageway with two portcullises, and extensive accommodation, including a prison, in the "Goghestower at the Great gateway of the Outer Bailey". The master of works was William of Marlow, presumably the mason engaged at the castle in 1284–91. Around 1296, the new prison at Chester Castle was the prison of Andrew Moray who had been captured at the Battle of Dunbar. Moray managed to escape the following year - it is not known how, or by what means, he made his escape: and headed north where he led a rising against Edward I’s rule in the north while William Wallace struck in Lanark and the south. Moray was badly wounded at the battle of Stirling Bridge - possibly struck by an arrow. His seal is found on two letters dated 11 October and 7 November so it is thought that Moray survived the battle but later died of his wounds. Several of the Scottish prisoners held at Chester had also been taken at the Battle of Dunbar, from which John Comyn, Earl of Buchan, and the earls of Atholl, Ross and Menteith, together with 130 knights and esquires were sent into captivity in England. Either then or a little earlier, a new inner gatehouse was built west of the Agricola Tower, which was blocked and given a new staircase, presumably in preparation for the conversion of its chapel into a treasury in 1301. By 1294 the castle comprised an inner bailey with hall, chapel, and apartments, and an outer bailey with great hall, exchequer, and further apartments for the king and queen, including separate chapels.

Samuel Lewis notes:

- "On the subjugation of Wales, in 1300, by Edward I., several of the Welsh chieftains did homage to his son, Edward of Carnarvon, then an infant, in Chester Castle."

Though the castle's military importance declined after 1300, in the early 14th century it was relatively well maintained. In Edward I's later years it seems to have been well supplied with arms and provisions, and was the base of a craftsman engaged in making weaponry (attilliator). Edward last visited the castle in 1301. In 1302, there was a fire in the Agricola Tower and the lower floor was remodelled entirely, with one of the doorways being bricked up. Meanwhile, Edward ensured that the heirs of the Welsh princes would trouble him no more:

- "As the King wills that Owain son of Dafydd ap Gruffudd, who is in the Constable’s custody in the castle, should be kept more securely than he has been previously, he orders the Constable to cause a strong house within the castle to be repaired as soon as possible, and to make a wooden cage bound with iron in that house in which Owain might be enclosed at night" - (Order from King Edward I to the Constable of Bristol Castle).

Sources and Links

- Edward as Crusader; (video)

- Life of Edward; (video)

Edward II

Edward's own son did not exactly prosper. The Earl of Chester became king (Edward II) in 1308. Edward II also repaired the castle and provided it with stores and armour, though elsewhere his castles suffered from neglect. There was still a resident staff of 12 in 1313. The king ordered the castle to be put into a state of defence in 1317, and after his fall in 1327 custody was granted to Thomas of Warwick and orders were issued for its provisioning and repair. In 1329 a new attilliator was appointed. By then, however, the castle seems to have served primarily as an administrative centre. The castle's principal officials resided in the inner ward, where in 1328 the justice of Chester's deputy had his hall, chamber, and a new kitchen, and where "Damory's Tower" contained the former chamber of the justice himself. The name probably comes from Richard Damory who was Chief Justice of Chester and by April 1318 had been appointed Edward III's guardian, by Edward II. Richard's younger brother was Roger Damory, a "favourite" of Edward II until displaced in the Kings affections by Hugh Despenser. As Damory's Tower was in the Inner Bailey, and clearly associated with the Judge's Lodgings, it is possible that it is the "octagonal" tower (similar to those from Edward I's castle at Caernafon) shown in the c1810 painting by Turner. In 1322 Chester castle was granted to Edward II's favourite (and lover), Hugh Despenser the younger (see: Earls of Chester for further notes).

The constable also then had his lodgings in the inner ward. The main administrative buildings, the shire hall and exchequer, were for long in the outer bailey, but in 1310 the shire hall was removed to a new position just outside the main gate. A new exchequer was built within the castle in 1355, but in 1401 it too was moved outside to a building adjoining the shire hall.

As noted above, Edward II was deposed in 1327. He died (supposedly horribly) later the same year. He never passed the Earldom of Chester on to his heir. A rumour that Edward II had been murdered (at Berkeley Castle) by means of a red hot iron was elaborated in a later history by Sir Thomas More (written 1512-19, published after 1535):

- "On the night of 11 October (1327 AD) while lying in on a bed [the king] was suddenly seized and, while a great mattress... weighed him down, a plumber's iron, heated intensely hot, was introduced through a tube into his secret parts so that it burned the inner portions beyond the intestines."

Holinshed states that the shrieks of the King were heard, through the thick stone walls, all over the town of Berkeley, but compared to what happened to Edward II's favourite and possible gay lover Hugh Despenser, this was quite mild. Despencer was judged a traitor and a thief, and sentenced to public execution by hanging, as a thief, and drawing and quartering, as a traitor. Additionally, he was sentenced to be disembowelled for having procured discord between the King and Queen, and to be beheaded, for returning to England after having been banished. Treason had also been the grounds for Gaveston's execution; the belief was that these men had misled the King rather than the King himself being guilty of folly. Immediately after the trial (24 November 1326), Despenser was dragged behind four horses to his place of execution, where a great fire was lit. He was stripped naked, and Biblical verses denouncing arrogance and evil were carved into his skin. He was then hanged from a gallows 50 ft (15 m) high, but cut down before he could choke to death. In Jean Froissart's account of the execution, Despenser was then tied to a ladder, and, in full view of the crowd, had his genitals sliced off and burned (in his still-conscious sight) then his entrails slowly pulled out, and, finally, his heart cut out and thrown into the fire. Professor Clare Sponsler says that Froissart is the only source to describe castration, where all other contemporary accounts have Despenser quartered, hanged, and beheaded. Just before he died, it is recorded that he let out a "ghastly inhuman howl", much to the delight and merriment of the spectators. Finally, his corpse was beheaded, his body cut into four pieces, and his head mounted on the gates of London. Roger Mortimer and Isabella feasted with their chief supporters, as they watched the execution.

It used to be thought by some that the beautiful frescos in the chapel of St Mary de Castro (upper part of the Agricola Tower) were painted by artists brought back from Europe by Edward II, but others have suggested Henry III, which now seems more likely (see above). While the English Heritage website says they were discovered in the 1980s, Lewis (see above) apparently mentions them as being visible in 1848. Mysterious stuff, history.

Writing in 1836, Hemingway describes the Agricola Tower as follows (noting the figures on the walls):

- ..its entrance is through a large Gothic door, probably of later workmanship. The lower room has a vaulted roof, strengthened with ordinary square couples. The upper had been a chapel, as appears by the holy water pot, and some figures, almost obsolete, painted on the walls. Its dimensions are nineteen feet four inches by sixteen feet six; the height also sixteen feet six. The roof is vaulted; but the couples, which are rounded, slender, and elegant, run down the walls, and rest on the connected capitals of five short, but beautiful round pillars, in the same style with those in the chapter-house of the cathedral, probably the work of the same architect.

Millennium festival trail marker for the Agricola Tower

The most complete and best-preserved fragment is the Visitation in the southern quadrant of the eastern bay. It shows Elizabeth holding her right hand under the Virgin’s chin, and is contained within a trefoil frame. Other narrative scenes have been positively identified, including the Adoration of the Magi, and it is considered likely that the vault was decorated with a series of images devoted to the Infancy of Christ. The fragmentary condition of the paintings makes it difficult to identify positively most of the remaining scenes, but it has been suggested that the Miracles of the Virgin is one of the themes, since some of the figures could be identified as the priest Theophilus and the repentant thief Ebbo, possibly shown being saved from death on the gallows by the intercession of the Virgin.

Frank Simpson also mentions the paintings as partly visible in 1928 and describes the interior of the chapel as follows:

- "The interior walls of the chapel have a coating of plaster about a quarter of an inch thick, some of which may still be seen on the walls. They were formerly ornamented with very fine frescoes. On either side of the light above the altar was a representation of Moses receiving the Tablets of the Commandments on the Mount, while the Devil, in nondescript form, is making an energetic attempt to seize them. This fresco was distinctly seen in 1810, when a sketch was made of it by John Musgrove, a well-known local artist, but, like the others, it is now entirely obliterated owing to damage to the plaster and numerous coats of lime and yellow wash. On the west side of the south (pointed) window, on the upper portion of the wall were the remains of a fresco, displaying a very beautiful face, looking east, with a mustache and short pointed beard, the head surmounted with what appeared to be a mitre. The right hand was closed, with the first finger pointing forward and the arm outstretched, below were traces of a flowing robe. During March and April (1928) numerous remains of these paintings were brought to light, the best being on the wall just below the groining of the first bay, east end of the right side. This represents a young man and woman embracing. The the left of the doorway near the groining is a hand grasping a sword and on the west wall is a goblet or chalice similar in shape to a champagne glass. The altar recess is filled with faint vestiges of paintings, but on the other side of the window above the recess, little is to be seen of the painting sketched by Musgrove in 1810. This is accounted for by the fact that little of the plaster is left on the wall, but there are other remnants of a frieze, just below the groining which surrounds the chapel. On the south side of the center of the groining appeared the head and shoulders of a horse. It is now clear, that all the walls and groining in the chapel were originally covered with frescoes, but owing to damp, neglect and damage caused by putting up shelves for storage purposes, much of the plaster has been broken off. The most striking feature of the relics of the paintings in this chapel is the beauty of the drawing and colouring of the faces, which appear to have been numberless. The paintings are now hardly visible, but when damped with a wet brush they stand out with all their beauty and richness of colouring."

Due to a leaking roof the frescos have suffered somewhat in recent years with the efflorescence of salts. However once the roof is fixed it is believed that these salts can be removed and the remaining frescoes restored. In the Buon ("true") method fresco pigment (insoluble, fine-ground, coloured particles) is mixed with room temperature water and is used on a thin layer of wet, fresh plaster, called the intonaco (after the Italian word for plaster). Because of the chemical makeup of the plaster, a binder is not required, as the pigment mixed solely with the water will sink into the intonaco, which itself becomes the medium holding the pigment. The pigment is absorbed by the wet plaster; after a number of hours, the plaster dries in reaction to air.

The following priests were chaplains or ‘Custodes Capelle’ at the chapel in the castle:

- Petre Trafforde (c.1360).

- John de Wylaston (c.1400).

- John de Thornton (during the reign of Henry V).

- John Trafford (c.1491).

In 1648 the well known Congregationalist Minister Samuel Eaton was the Chaplain. The heavy, copper-plated door on the chapel dates from the early nineteenth century, when the chapel was used as a gunpowder store.

Edward III

In 1328 The justice of Chester’s deputy had a hall, chamber and new kitchen constructed in the inner bailey. In 1329 A new attilliator (weapons maker) was appointed. However, after 1329 the fabric suffered long periods of neglect, punctuated by occasional, often inadequate, refurbishments. In 1337, a survey by the Justiciary and four members of the prince’s council reported that 20 perches (100 yards) of wall, seemingly that of the entire Outer Bailey, were being rebuilt ("but was not yet half-finished") and repairs were undertaken on the constable’s hall and other buildings of the inner ward as well as the bridges leading to the two gatehouses. By 1347 the "Gonkes Tower", "Chapel Tower", and "Damory's Tower", the "Great Chapel", the "Great chamber at the east end of the hall", the "Earl's smaller chamber and its chapel", and the great hall itself were all in disrepair.

During the reign of Edward III (1327-77) a Roger de Ridelegh attempted to escape from the prison by removing some of the stones. John Sumerill (the deputy constable of the castle) was indicted for striking a prisoner, John le Parker, and for putting him in the stocks with irons, from which punishment le Parker later died. The punishment of loading a prisoner with weights or "pressing" a prisoner to death was also introduced at this time.

Sources and LInks

- A note on the deaths of Edward II - Ian Mortimer

Bollingbroke and Richard II

Richard II (ruled 1377-1399)was another mild-mannered king who favoured genteel interests like fine food, insisted spoons be used at his court and is said to have invented the handkerchief. Like Edward II, he had a militaristic father but was a much weaker character himself. For more on Richard see Royal Treasure.

In the last years of Richard II's reign the castle again became a favoured royal base. In 1396 the office of master mason, which had lapsed in 1374, was reintroduced, and in 1397 the office of keeper of the king's artillery in Cheshire and Flintshire first appeared. The first known illustration of artillery in Britain is from 1327. "Ribaldis" were first mentioned in the English Privy Wardrobe accounts during preparations for the Battle of Crécy in 1346. These are believed to have shot large arrows and simplistic grapeshot, but they were so important they were directly controlled by the Royal Wardrobe. According to the contemporary poet Jean Froissart, the English cannon made "two or three discharges on the Genoese", which is taken to mean individual shots by two or three guns because of the time taken to reload such primitive artillery. Similar cannon appeared at the Siege of Calais (1346-47) and by the 1380s, the "ribaudekin" had become mounted on wheels. However the artillery of Richard's time could not yet threaten a castle with demolition: it was still an anti-personnel weapon or perhaps a means to intimidate opposing troops and scare horses.

The castle evidently continued in use as a place of detention. Thomas le Wodeward, deputy constable of the castle, took delivery of the following new supplies in 1397: 11 iron collars and 2 gross of iron chain; 2 pairs of iron belts with shackles; 2 pairs of iron handcuffs with 4 iron shackles; 7 pairs of iron feet fetters with 3 shackles; 1 hasp for the stocks.

Also in 1397, Richard II created the title "Prince of Cheshire", which he awarded to himself. His personal bodyguard was made up of Cheshire bowmen who were described as being intolerably arrogant, insolent ruffians who lived on far too intimate terms with king. This bodyguard was divided into watches commanded by: Ranulf of Davenport, John of Legh, Richard of Cholmondeley, Adam of Bostock, Thomas of Beeston, and Thomas Halford. In 1399 Richard II had a heated bathroom constructed in Chester Castle (costing £70). It was paneled with Norwegian timber. His apartments were redecorated with cushions and fine silk hangings, but he would not enjoy it for long.

In 1399 Richard II granted 3000 gold marks to the people of Chester (widows and dependents of soldiers killed during the battle) who had suffered as a result of the battle of Radcot Bridge (1387). This was distributed by Robert de Legh (Sheriff of Chester) at the Exchequer court in the Castle. Later in 1399, his cousin, Henry Bollingbroke, later Henry IV but then just Duke of Lancaster, landed in Britain after exile and took Chester without a fight. The Duke stayed at Chester Castle for 12 days, amusing himself by drinking the king's wine, wasting fields and pillaging houses. and presumably enjoying the use of Richard II's "Norwegian Wood" bathroom. While there ("this thief, this traitor, Bolingbroke, who all this while hath revell'd in the night"), he also found time to secure the arrest, incarceration in the Gowestower (outer gatehouse tower) and execution of Sir Peirs Legh of Lyme, one of Richard's leading retainers in Cheshire and the brother of the Sheriff - Legh's head was placed on the Eastgate.

Henry then marched against Richard at Fflint Castle to which Richard had been lured from the safety of Conwy Castle. Richard surrendered, but not before trying to escape dressed as a monk. Shortly before his capture, Richard II hid his Royal Treasure of 100,000 marks in gold coin and 100,000 marks in other precious objects (about £200 million in today's money) in the Chester area. Some say at Beeston Castle, some say elsewhere - but the hoard has never been found.

According to Stowe's Annals, following the capture of the King, Bollinbrooke

- " with a high sharp voice, badde bring forth the king's horses; and then two little naggs, not worth forty francs, were brought forth."

The king was set on the one, and the earl of Salisbury on the other, and thus the duke brought the king from Flint to Chester, where he was delivered to the duke of Gloucester's son, who led him straight to the castle (still wearing the monk's habit in which he had attempted to escape) and "lodged" them in Chester Castle for a few days (possibly in a tower over the outer or inner gateway, possibly in the Agricola Tower), while Henry received a deputation from the City of London renouncing their fealty to the prisoner. Imprisoned with Richard were some of his loyal supporters such as Janico d’Artois and James Darteys, who refused to lay aside Richard's badge of the white hart. Afterwards, Richard was escorted to Westminster, where he was persuaded to abdicate. Bollingbroke usurped Richard and became Henry IV.

Rebellions continued throughout the first ten years of Henry IV's reign, including the revolt of Owain Glyndŵr, who declared himself Prince of Wales in 1400, and the rebellion of Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland. Early in 1400, there was a revolt in Cheshire, linked with the Epiphany Rising. Those involved included prominent members of Richard's Cheshire retinue and a large group of townsmen from Chester, 28 of whom, dressed in the "white hart" livery of the deposed monarch, marched to the Eastgate on January 10th 1400, removed Peir's Legh's head from the Eastgate, and unsuccessfully besieged the castle, then held by the Chamberlain of Chester, the Sheriff of Cheshire, and the Constable, William Venables of Kinderton. The rebellion temporarily enhanced the castle's military importance: early in 1400 it was garrisoned by 8 men-at-arms and 35 archers, and even in 1404 it was still protected by 8 archers. It also contained considerable stores of weapons and supplies.

The deposed King Richard died in prison at Pontefract Castle later in the year (by 17 February 1400), possibly having been starved to death on Henry's orders.

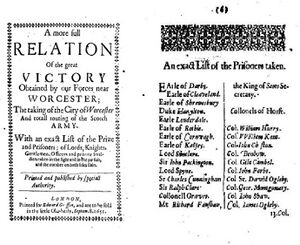

Courts of another kind