Grosvenor Museum

The Grosvenor Museum (official website) holds Chester's biggest collection of local and international history. It covers 2,000 years of Cestrian life spread over three floors of a classic 19th century building. It is truly one of the most interesting "local" museums in England and a "must see" when visiting Chester. And best of all – it's completely free! It is located on Grosvenor Street.

History

The Grosvenor Museum was founded in 1885, and its origins are linked to the start of the Chester Society for Natural Science, Literature and Art, founded by Charles Kingsley in 1871. Charles Kingsley was a Canon of Chester Cathedral from 1871 to 1873. He brought together many local naturalists, and the Society built up large and important natural history collections. The building of a local museum was first suggested in 1871, to house the collections and use them for teaching. Kingsley wrote many fictional works, but also wrote the lesser known "Town Geology" while in Chester.

In 1873, the Natural Science Society joined forces with the Chester Archaeological Society and the Schools of Science and Art to raise money for the museum. The plan was to build a museum with lecture rooms, to house the collections and libraries from all three groups.A plot of land was bought in Grosvenor Street and £11,000 was raised, including a donation of £4,000 from the first Duke of Westminster. The architect was Thomas Meakin Lockwood of Chester.

The museum is built of red brick with sandstone dressings in a free Renaissance style. On the façade, the reclining spandrels of the portal represent science and art, whilst the Dutch gables are carved with peacocks flanked by the talbot supporters of the Grosvenor arms. In the entrance hall, the mosaic decoration featuring the city arms, was made by Italian craftsmen from the Manchester firm of Ludwig Oppenheimer, and each of the four Shap granite columns was turned from a single piece of stone. Ludwig Oppenheimer, was born into an Orthodox Jewish merchant banking family in Brunswick, Germany, in 1830. Sent to Manchester to improve his English, he fell in love with Susan McCulloch, the niece of the Scottish couple with whom he took lodgings and converted to Christianity. As a result he was cut off by his parents and became an apprentice mosaicist in Venice, returning to Manchester to marry Susan and to establish a mosaics business in the city in 1865. Some of his best work can be seen in the Honan Chapel at the University of Cork.

The foundation stone was laid by the Duke on 3 February 1885, and he officially opened the museum on 9 August 1886. Named after the Duke's family, the building's full title was "The Grosvenor Museum of Natural History and Archaeology, with Schools of Science and Art, for Chester, Cheshire and North Wales".

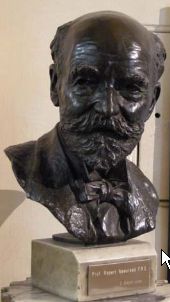

Robert Newstead held the post of curator from 1886-1913 and then from 1922 to 1947.He was supported in this work by his brother Alfred. Robert Newstead later became Professor Emeritus of Entomology at Liverpool University. He was also a scholar of considerable distinction in the field of archaeology, and was made a freeman of the city in 1936. We use a photograph of Prof Newstead for our "guestbook" icon.

The City of Chester officially took over the administration of the museum in 1915, and total control of the collections and displays in 1938. Graham Webster was appointed curator after Robert Newstead died in 1947. Webster was an expert on the Roman army, one of the modern founders of the study of Roman pottery in Britain and did pioneering work in many of the more obscure areas of Romano-British studies, ranging from his early work on the use of coal in Roman Britain through to his last major work, on Romano-Celtic religion. The Society of Antiquaries reported in 1950 that they were:

- "..much impressed by the remarkable progress of the Curator since his appointment. Though the work of rearrangement is far from complete, sufficient has already been accomplished to justify the belief that, when the present plans have been carried out, the Museum will rank with the most modern and attractive displays of archaeological material in the country."

Graham Webster devised the Newstead Gallery, which was opened in 1953 and named after Robert Newstead. In 1955 the first period room, the Victorian Parlour, was opened to the public in the Period House at number 20 Castle Street, which Graham Webster had saved from demolition.

In 1989, the new Art Gallery was created, and the museum came under the new Leisure Services section of the City Council. Major structural work in 1990 was the perfect opportunity to refurbish all the public areas, including the entrance hall and main galleries. The Roman Stones and Natural History Galleries were redisplayed and a new Silver Gallery created. In 1992, HRH The Prince of Wales (Earl of Chester) reopened the museum after refurbishment. In 1993, the Webster Roman Stones Gallery won the North West Museum of the Year Award. In 1999, the Museum was awarded a £300,000 grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund to undertake a scheme of access improvements to the ground floor, which included installing a disabled toilet and stair lifts, and building a new "conservatory" to house the shop. The museum now has over 100,000 visitors each year.

In April 2007, there was a public outcry when Chester City Council mooted the idea of moving the Grosvenor Museum to a new site outside the city centre, possibly to the Greyhound Park development at Sealand. The reason given was the current premises is too small now. It remains to be seen what the future holds.

Collections

Webster Roman Stones Gallery

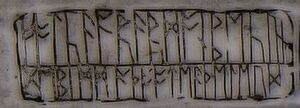

The museum houses the largest collection of Roman tombstones from a single site in Britain. With a few exceptions, all the stones in the gallery had been reused at some time to repair the City Walls. The tombstones on display tell you something about the lives of the soldiers, slaves, women and children who lived in Roman Chester. The gallery takes you on a walk through a Roman cemetery. Four altars to Roman gods include one to Nemesis, the goddess of fate or destiny. Thirty five tombstones are on display. One of the finest pieces of Roman sculpture in the museum shows a fragment of a scene with a wounded barbarian lying defiantly under the legs of his opponent's horse. His spear is broken but he still clings onto his shield. The complete stone commemorated a Roman cavalryman whose name and likeness are now lost.

The first few were found in 1883. More were found in 1887, buried inside the lower part of the City Walls near the Phoenix Tower. Between 1883 and 1892, over 150 tombstones were found in the north wall. This is still the most spectacular archaeological find made in Chester. The walls were probably repaired later in the Roman period between 300 and 400 CE. Why the tombstones were used is a mystery. However, they were well preserved inside the wall and survived unharmed for 1500 years.

Another feature of the gallery is the reconstruction of an optio's quarters complete with the figure of an optio. The optio was second in command to the centurion and was responsible for book keeping and listing the pay, sickness and personal details of each soldier.

Newstead Gallery

The gallery tells the story of Roman Chester including the Roman Legio XX and its fortress, coinage, pottery, glass, religion, trade and everyday life. Guarding the entrance to the gallery is a lifesize model of a Roman legionary of about 60 CE which shows how they dressed.

Two highlights of the gallery are the military diplomas and the collection of lead waterpipes and ingots found in or near Chester. Military diplomas were given to auxillary soldiers who had served in the army for 25 years. The diplomas were inscribed on bronze tablets. They gave Roman citizenship to the men and their children and made their marriages legal. Only 13 diplomas have been found in Britain. The most complete was found in Malpas, Cheshire in 1821. It is dated 19 January 104 and was made out to horsemen and foot soldiers serving under Lucius Neratius Marcellus, Governor of Britain.

Lead ores were very important to the Romans not only for the lead but also for the silver found in the ore. The lead was mined from the Clwyd Hills. One of the lead pipes on display was made in 79 CE. Chester's lead industry continued after the Romans left with the Leadworks on the edge of the city center only closing in 2001.

A model of the principia shows the headquarters building inside the fortress of Roman Chester. It contained a large courtyard surrounded by offices and stores. You can only see a few traces of this great Roman building today. St Peter's Church at the High Cross now stands on the site of the entrance to the principia. The model of the Roman Amphitheatre at Chester shows a reconstruction of the largest stone amphitheater in Britain. It could hold over 6,000 spectators. One of it's main purposess was for training the legionaries in fighting techniques. A model of the whole Roman fortress at Chester shows a bird's-eye view of the fortress around 220 CE.

The Grosvenor Museum contains a skeleton recovered from the bottom of a Roman well near the site of Chester Castle. Whoever it was, they had broken their leg earlier in life and it had been badly set, so they would have walked with a limp. It appears that the well was near the site of a fire which happened at around the time that the body ended up in the well.

Art Gallery

Most of the Museum's finest paintings are shown here, hung two deep against gold moire and enhanced by sculpture and furniture. A remarkable triple portrait of Mary Done, painted around 1635-38 by John Dobson, shows her contemplating her own bust, which has closed eyes like a death mask. Her son Sir John Crewe, Chief Forester of Delamere, was painted in 1682 by John Michael Wright, one of the most cosmopolitan figures in 17th century British art. A subsequent Chief Forester of Delamere, John Arderne, was painted about 1746 by Arthur Devis in his "characteristically neat and genteel style".

One work of local importance is a portrait of William Aldersey. Aldersey followed in his father's footsteps as a merchant ironmonger and so successful in overseas trade that he became a founding member of the East India Company in 1600, and is said to have been named in the patent incorporating the Company dated 31 December 1600 (although his name does not appear in available texts - he was more likely one of the 125 shareholders, rather than one of the 24 directors named in the patent). This proved to be an extremely lucrative investment, for although he had to subscribe £240 per share during 1601, the distributed profit on the first voyage by 1603 was nearly 300 per cent, and over all the East India voyages up to 1616 was never less than 220 per cent. He served as mayor of Chester in 1595–6 and 1613–4 and was particularly interested in the troops and horses which sailed from Chester to support the standing army in Ireland. Aldersey himself recorded the numbers and county of origin of the troops and horses dispatched between 1594 and 1616. It is said that his pride in this related to a "special barracks" he had built for that traffic, and to Chester’s efficiency in revictualing warships. The presence of so many troops also brought problems. Demands strained local markets, especially during the shortages of the later 1590s: prices rose, ships' masters demanded large payments, there were difficulties with the authorities of Liverpool, disaffected men deserted in droves and were rarely captured, weapons were often found to be defective, moneys were embezzled, profiteering was rife, and Chester earned a reputation as a 'robber's cave'. Disorderly conduct was frequent, especially when troops were delayed by bad weather or lack of ships. To contain it, in 1594 the mayor erected a gibbet at the High Cross. It may well be that Aldersey's interest in the origin of the troops, his "special barracks" etc. had less to do with any civic pride, and more to do with keeping the peace in the presence of a large number of frequently drunken and unruly troops.

Between his work and his civic duties, Aldersey studied Chester's Roman archaeology and the documentation of its medieval re-emergence. He is particularly remembered for his compilation of a list of the past mayors of Chester. The list survives to this day in a badly damaged memorandum book which was handed down through the Leche family. Aldersey’s last honour was to attend a civic dinner when James I visited Chester in August 1616. As the most senior alderman, he presented the king with a gold "standing bowl" chock full of gold coins (100 Jacobins) on the city’s behalf. He records the event himself:

- "12 October 1616 - The Kinges maiesty Came the 23rd day of august to the Lea hall to Sir George Calueley and there had a banquet, and from thence the same day to the Citty of Chester, where he was banqueted in the pentice, and presented with a Cupp of gold by the Citty. and from thence went to Vale riall [word cancelled] the same night beinge Saturday where he rested till mondey, and then came to the nante wiche that night and so away." - ALDERSEY FAMILY COLLECTION CR 469.

Sculpture plays a prominent role in the gallery, and includes a low-relief plaster medallion of about 1852 by the Pre-Raphaelite sculptor Alexander Munro depicting Constance, Countess Grosvenor, later Duchess of Westminster. In 1879 her brother, Lord Ronald Gower, made a bronze statuette of the Prime Minister, William Ewart Gladstone, who lived at Hawarden Castle near Chester. The collection extends into the 20th century with two pairs of Wedgwood basaltes ware vases, originally made for Winnington Hall at Northwich in 1921, and a brilliant likeness of Canon Maurice Ridgway, the great expert on Chester silver, painted by Paul Brason in 1994.

The museum houses over 700 pictures of Chester. A painting by the Flemish artist Pieter Tillemans, dating between 1710 and 1734, shows horse racing on the Roodee in front of the City Walls. A mid-19th century view shows the Cathedral before the major restoration in 1868-76, when much of its soft red sandstone exterior was refaced. Another mid-19th century painting by W. White shows the King Charles Tower, on which Charles I stood in 1645 while his army was being defeated by the Parliamentarians at Rowton Moor in the Civil War.

The gallery also contains furniture and includes a card table, veneered with rosewood and inlaid with brass, which is signed and dated 1824 by the Chester cabinetmaker John Crewe McKay. Chester's greatest sporting artist was William Tasker, noted for his portraits of winners at the Chester races, and the gallery includes his painting of Millipede from 1843.

As well as local artists and subjects, the history of art collecting in Chester is represented in the gallery, with works such as Feeding the Ducks, a highly-finished painting of the mid-19th century by John Frederick Herring Senior, which came from Hoole Hall.

Ridgway Silver Gallery

The museum has a superb permanent collection of silver. A number of important additional loans make this the largest display of Chester-related silver in the world, and the first half of the gallery tells the story of Chester-assayed silver. Early Chester silver begins with communion cups from the 1570s, but mainly covers the work of the 1680s and 1690s including tankards, a jug and an elegant two-handled cup. The Richardson family dominated the production of silver in 18th century Chester, and their work is celebrated in three cases. The greatest Chester silversmith was Richard Richardson II. His table basket of 1765 typifies the delicacy, lightness and elegance of the Rococo style.

The Assay Office in Chester has interesting roots. Although the power of the various trade guilds in Chester was generally reduced during the 18thC. an exception to this general decline were the Goldsmiths. Initially, the Goldsmiths had been under the control of the Goldsmiths of London which so dominated the trade that provincial goldsmiths almost became extinct: during the Civil War the Goldsmith guild in Chester had but a single member. With the restoration and the increased demand for church plate there was something of a revival and the Goldsmiths guild made the prudent move of admiting the Clockmakers within its ranks in 1663. By 1687 the Goldsmiths guild now had eight members and took the step of setting up its own Assay Office to attest to the quality of gold and silver works being produced and keep a register of makers-marks. This independent assay office was closed in 1697. The official Chester Assay Office was reopened in 1701 under the Plate Assay Act of 1700, which made Chester an official assay town, incorporated the goldsmiths and silversmiths under two wardens, and re-established the office of assay master, to be elected by the company. The Assay Office moved into premises in Goss Street in 1749, and continued to function until 1962, when it was closed at its function transferred to Birmingham.

Silver in Georgian Chester was produced by a number of makers in addition to the Richardsons. A wide variety of domestic silver is on display, including a finely engraved two-handled cup, a cream boat and a wax taper box.

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries the Lowe family dominated the story of Chester silver. Their finest piece of work is a hot water jug of 1830 by George Lowe I. Also on display is the last piece of silver hallmarked at the Chester Assay Office before its closure in 1962, and a new bowl, commissioned by the then owners of Lowe & Sons to celebrate the opening of the gallery. Lowe and Sons was founded in Chester by the first George Lowe in 1770 and has occupied the premises in Bridge Street Row since 1804. Harold Lowe, a grandson of George Lowe of Chester, was fifth officer on Titanic and one of the heroes of its sinking in 1912. Harold Lowe grew up in Barmouth where his father ran a branch of Lowe and Sons and was a regular visitor to the Chester store, then owned by his uncle. Harold did have the opportunity to join the family business but instead chose to run away to sea. Lowe is not the only connection between Chester and the doomed ship: Walter Wynn, a surviving deckhand, was born in Chester; Lilian, daughter of Thomas Hughes perished in the sinking; and, the ship which accompanied the Carpathia to New York was USS Chester.

The second half of the gallery starts with the Delamere Horn and the Arderne Tankard. The tankard is a splendid piece from 1669, with lions forming the feet and thumbpiece and a dolphin handle. An impressive array of Chester race trophies illustrate the patronage of Chester City Council and the Grosvenor family. In addition to two large silver punch bowls and a solid gold tumbler cup, the display includes a pair of silver-gilt cups. These were presented by the second Earl Grosvenor in 1814 and 1815.

The gallery houses some exceptionally rare pieces of silver associated with the County Palatine of Chester. A pair of seal matrices made in 1706 for the Exchequer of the County Palatine by John Roos, Chief Engraver of the Royal seals of England, are the only surviving examples from Chester. A seal salver, made in 1759 for Sir John Willes, Chief Justice of the County Palatine, is elaborately engraved with his seal of office.

Three cases of local church plate begin with 18th century silver from the Nonconformist Matthew Henry's Chapel in Trinity Street. The 18th century Cheshire church plate from Stoak and Tarvin includes a handsome ewer and cup. The Chester church plate purchased from four redundant churches is displayed in the context of a rich crimson and gold altar.

The gallery ends with a glittering array of the Marquess of Ormonde's silver. A dinner service and silver-gilt presentation pieces are displayed on a tiered buffet. The silver was given to the Museum after acceptance in lieu of taxation. It includes a beautiful pair of Rococo table candlesticks and pieces by the greatest Regency silversmith, Paul Storr.

The gallery is named after Maurice H Ridgeway (1918-2002) the paramount scholar of Chester silver. Ridgway was born in Stockport, where his father was vicar of St George’s church. The family moved to Tarvin and he attended the King’s School, Chester, followed by St David’s College, Lampeter. He completed his training for the Anglican ministry at Westcott House, Cambridge, and served forty-two years in the diocese of Chester. After being ordained deacon in 1941 and priest in 1942 he served as curate of Grappenhall from 1941 and of Hale from 1944. In 1949 he became vicar of Bunbury, where he restored one of Cheshire’s major Perpendicular churches following severe war damage, employing Marshall Sisson to rebuild the nave and aisle roofs in 1950 and commissioning three superb stained glass windows from Christopher Webb. He was vicar of Bowden from 1962 and became an honorary canon of Chester Cathedral in 1966. Canon Ridgway’s study of Chester silver began when Sir Leonard Stone,chairman of the Board of Trade’s Departmental Committee on Hallmarking,asked him to do some of the background research on Chester for the 1959 report to Parliament, which led to the closure of the Chester Assay office in 1962. He was the editor of The Cheshire Sheaf and The Bunbury Papers and his numerous published guides, articles and reports include a survey of stained and painted glass in Cheshire and the history of Beeston Castle.

- Harold Lowe and his connection with Chester;

- The Lowe family;

Kingsley Natural History Gallery

The gallery has four themed areas: the history of the Victorian Chester naturalists; local species and projects; local environmental projects and a hands-on Activity Room.

The Victorian history begins with the life of Charles Kingsley (1819-1875). Kingsley was Canon of Chester Cathedral from 1871 to 1874 and founded the Chester Society of Natural Science. A highlight of the gallery is the mock Victorian naturalist's study. It contains the moth collection of Herbert Dobie, many of the moths collected from the first electric street lights in Chester.

Historically important Cheshire collections include cited birds and hawkmoths. The Chirotherium fossil footprints are from Storeton Quarry on Wirral and include a computer animation of what Chirotherium supposedly looked like. Chirotherium tracks were first found in German Triassic sandstones in 1834, and later in England in 1838. They were found before dinosaurs were known and initial models of the trackmaker proposed that it was a bear or ape, which walked with its feet crossed. This proposal was necessary to explain the toe on the outside. The geology of Britain is such that the oldest rocks are exposed to the west and the youngest to the east. This means that the River Dee crosses rocks from several geological periods on its journey from source to sea. This fact was first noticed by William Smith, who, in 1815, published the first geological map of Britain. In 1817 Smith drew a remarkable geological section from Snowdon to London. Unfortunately, his maps were soon plagiarised by the Geological Society of London and sold for prices lower than he was asking. He went into debt, and despite the sale of his geological collection to the British Museum, he finally became bankrupt in 1819 and was sent to debtor's prison. On 31 August 1819 Smith was released from King's Bench Prison in London. He returned to his home of fourteen years at 15 Buckingham Street to find a bailiff at the door and his home and property seized. Subsequent modern geological maps have been based on Smith's original work, of which less than 40 copies have survived, one of which is in the Grosvenor Museum at Chester.

Interactive displays include "A Look at Cheshire Wildlife" with animal calls and bird songs; a Micrarium to view microscope slides and a Videoscope. The Activity Room is open only at weekends. Visitors can explore the insect and fossil collections and handle objects.

Visiting in 2017, the gallery has had a makeover, and frankly, has become a bit dull. There is no "Indiana Jones" feel any more and it's all rather THX1138.

Museum Cafe

This is a rather strange affair. It consists of the "The King’s Arms Kitchen" (as described by Steve Howe) the transplanted interior of a public house of the same name originally located up a narrow alley by Eastgate in the city centre. The ‘Honourable Incorporation of the King’s Arms Kitchen’ was a gentleman’s club which met in the ‘Mayor’s Parlour’ of the pub. Some time around 1770 a group of tradesmen met at the King's Arm's to form a 'mock' City Assembly of their own. This satirical imitation of the Corporation had an elected mayor, recorder, town clerk, sheriffs, aldermen and common councilmen. The location was said to be that of a place where Charles I is supposed to have hidden for a month after the defeat of his army at Rowtonon 24th September 1645. This is almost certainly untrue as Charles withdrew from Chester the next day with his remaining 2,400 horse, heading to Denbigh Castle before moving on to Newark-on-Trent. The Sporting Review of 1869 reports an even more unlikely tale:

- "The King's Arms Kitchen" as it was called, was errected in 1861, on the site of a tavern dating back to the days of the First Charles, who is traditionally said to have established the mimic Corporation still kept up in the house."

Members of the club met to elect officials and elect new members, but mostly to lay bets and drink. Their minute book records such details as:

- "November 8th, 1815: Mr Magennis bet Joseph Bellis glasses round (nine members present) that the carters demand one shilling per cart for carrying linen from Crane to the Linen Hall."

- "Mr Samuel Davies lay the undermentioned six glasses each that he is married in the course of a fortnight (Mr Davies won)."

Boards around the room list the names of the people holding the various officies. The boards are somewhat similar to those in the "Bird in Hand" at Guilden Sutton. These boards had become unreadable with the passage of time, but infra-red photography allowed them to be re-lettered in 1979, when the interior of the kitchen was removed from the pub, which was being demolished, to the museum. On either side of the "mayors chair" (made in 1821 by "Mr Alderman" Hodkinson) are replicas of the city sword and mace, while the originals belonging to the King's Arms Kitchen had been stolen, new copies have been made and hung as they would have been. The "fine" for anyone sitting in the mayor's chair (other then the mayor) was a round of drinks for all present. The clock is by S. Moreton of Boughton.

There was seemingly a bar on clergymen being elected to the membership. Only one is recorded in the minute-book as being admitted:

- "March 21st 1805: the Rev Lucius Carey was proposed by Mr Simpson and seconded by Sheriff Paul to become a member .. and was unanimously accepted .. the Town Clerk's fee being reserved. Afterwards expelled."

It seems that there was good sense in expelling Carey. The Rev Lucius Carey was an Irish clergyman (whether Anglican or Roman is not known) who, according to the Admiralty records (1.1532 Capt Birchall, 17th July 1804) was in Chester and:

- "..had contracted the unclerical habit of carrying pistols and too much liquor. In this condition he was found late one night knocking in a very violent manner at the door of the "Pied Bull", and swearing that, while none should keep him out, any who refused to assist him in breaking in should be shot down forthwith. Sam Burrows, the ex-beadle, happened to be passing at that moment. He seized the drunken cleric and with the assitance of James Howell, one of the city watchmen, forcibly removed him to the watch-house, whence he was next day taken before the mayor and bound over to appear at the Sessions. Now it happened that certain members of the local press-gang were Carey's boon companions, so that no sooner did he leave the presence of the mayor than he looked them up. That same evening Burrows was missing. Carey had found him a "hard bed", otherwise a berth on board a man-o-war."

The "Pied Bull" still exists in Northgate Street, and Burrows apparently escaped the Navy to eventually become the City Hangman. It also appears that Burrows may himself at one time have been a member of the "Press Gang".

On the ceiling of the "King's Arms Kitchen" is a wooden boss, bearing the words: "PERSEVERE UNDER THE ROSE". The Latin phrase "sub rosa" means "under the rose" and is used in English to denote secrecy or confidentiality. Paintings of roses on the ceilings of Roman banquet rooms were also a reminder that things said under the influence of wine (sub vino) should also remain sub rosa. In the Middle Ages a rose suspended from the ceiling of a council chamber similarly pledged all present (those under the rose) to secrecy.

There is a coin operated drinks machine just outside, but if you want to eat then bring your own packed lunch, which you are quite welcome to eat here, as there is no food on sale!

Museum Shop

The shop stocks a wide range of Books, greetings cards and historical gifts. Some few of the books are available as ebooks on this site, but many are only obtainable from the Museum. The staff are very helpful.

Exhibitions

20 Castle Street

20 Castle Street, behind the museum, is a town house that takes you back to home life from the 17th century to the 1920s; including a Victorian kitchen, a Georgian drawing room, a nursery and even a fully fitted Edwardian bathroom. There are some anchronistic features in some of the displays (probably there as a joke) - in the Victorian Schoolroom there is a chart on the wall explaining "Bingo" which dates from well after the Victorian Period - at the time the call of "Bingo" would only have been used by Customs Inspectors when they made a "find". The chart uses "Doctor's Orders" for the number nine, which dates it to after WW2 when "Number 9" was a laxative pill given out by army doctors. It also refers to "Number 10" as "Mrs May's Den".

Bingo, or "By Jingo" is a "minced oath" and a transparent euphemism for "by Jesus" and does have Victorian connections. "Jingoism" arose from an 1878 song with the words "We don't want to fight but by Jingo if we do, We've got the ships, we've got the men, we've got the money too, We've fought the Bear before, and while we're Britons true, The Russians shall not have Constantinople." The use of the chart is thefore a clever pun on several levels. Looking closely, the "Schoolgirl" also has a mobile phone or remote control on her desk and the boy in the sailor-suit is wearing headphones.

Exhibition Galleries

These host visiting exhibitions. Details of current exhibitions can be found on the museum website.

History Hub

The Grosvenor Museum houses the "History Hub" - just turn left on entering. This comprises a small library of books relating to Chester and a few computer terminals which can be used to access historical databases. Helpful staff are on hand to assist with enquiries.

Sources and Links