We'll be deploying 1.43 to ShoutWiki sites this weekend. Staff will be working all weekend to deal with any unforeseen bugs that crop up.

CreateWiki will not be available immediately after the upgrade; however, we expect the rewrite to be completed during this release cycle.

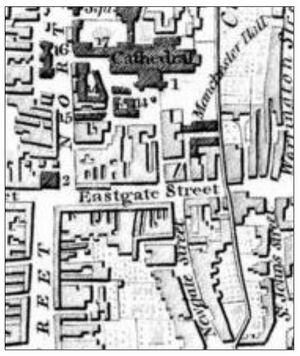

Newgate Street

History

Roman

In Roman Chester the upper end of what was later to become "Fleshmongers Lane" is believed to have been the site of the "Tribunorum" houses assigned to the main officers (tribunes and praefectus castorum) of the legion beneath the actual commander. As what is now Eastgate Street was used for ceremonial purposes, the frontage onto it from the south would probably have been quite ornate. Legions were commanded by a legionary legate (legatus). Six tribunes were posted to a legion, their duties and responsibilities were more a political position than a military rank. Young men of Equestrian rank often served as military tribune as a stepping stone to the Senate. The second-in-command to the legate was the tribunus laticlavius or 'broad-stripe' tribune (named after the width of the stripe used to demarcate him on his tunic and toga), usually a young man of Senatorial rank. He was given this position to learn and watch the actions of the legate. They often found themselves leading their unit in the absence of a legate. In contrast to the broad-stripe tribune, the other five 'thin stripe' tribunes were lower in rank, and were called the tribuni angusticlavii. These 'officer cadets' were men of equestrian rank who had military experience, and yet had no authority: they were allowed to sit on a court martial but they held no power in battle. Most thin-stripe tribunes served the legionary legate, yet a lucky few (such as Agricola) were selected to serve on the staff of the provincial governor. Archaeological investigation of the homes of these people would have been fascinating.

Unfortunately, reckless development during the 1960's destroyed any surviving structure. Dennis Petch, Curator of the Grosvenor Museum during the 1960s, is reported to have recalled bitterly that:

- "..the developer refused to give permission for any formal excavation once his work on the site had begun... with customary efficiency Laing's immediately commenced the earthworks for underground storage and delivery bays for shops to be built in the precinct above... it was soon clear that the great colonnaded hall under the arcade formed part of the same complex and was in all probability one of the earliest of the covered palaestrae of the north-western provinces of the Roman Empire. Even after the great size and high degree of preservation of the building had been clearly demonstrated, and protests against its impending destruction were made at local and national level, commercial considerations prevailed, effectively limiting our gathering of site data to piecemeal observation and recording at the pleasure of the contractor, supplemented by very little formal excavation. This was not a very satisfactory way of proceeding in the case of such an important building which had apparently begun its life in the early years of the fortress and was still in use in the third century. This debacle attracted a great deal of public attention and criticism, and the upshot was a general conviction that such vandalism should not be allowed to recur."

Steve Howe of the Virtual Stroll website has collected many stories from men who worked on the construction site of the purposeful and wanton destruction of any remains found, so as to prevent any delay to construction by archaeological investigations. In one case, a perfectly preserved mosaiic floor was found and the workers were told to wreck it with the back-hoe of a digger.

One of the several relics of Roman Chester which was recovered in this area was a Roman altar found in 1693 on the corner of Newgate Street and Eastgate Street. The inscription on this reads:

- "Pro sal(ute) Domin[oru]m N(ostrorum) Invict[i]ssimorum Aug(ustorum) Genio loci Fl[a]vius Long[us] trib(unus) mil(itum) leg(ionis) XX [V(aleriae) V(ictricis)] [et] Longinus fil(ius) eius domo Samosata v(otum) s(olverunt)" (For the welfare of our lords, the most invincible Emperors, to the Genius of the place Flavius Longus, military tribune of the Twentieth Legion Valeria Victrix, and Longinus, his son, from Samosata, fulfilled their vow.)

As this was the location of the houses of the tribunes it is possible that this was a domestic altar and Flavius Longus actually lived here. Samosata was an ancient city on the right (west) bank of the Euphrates whose ruins existed near the modern city of Samsat, Adıyaman Province, Turkey until the site was flooded by the construction of the Atatürk Dam.

Further down what is now Newgate Street would have been an area composed of barracks associated with the south-east corner of the Roman city. And a few scant remains have been found to indicate this. In 1748, while digging "very deep in Mr Kenrick's garden", a centurial stone was found. This is now in the Grosvenor Museum as item CHEGM: 1999.6.16. The stone is that of "Ocratius Maximus" and the inscription reads:

- "From the first cohort the century of Ocratius Maximus (built this); Lucius Mu(…) P(…) (made the inscription)."

This is a type of stone which would have been set in the city wall to indicate who was responsible for building it. A very few other such stones have been found in Chester. Other finds in the area include an altar to Mars found in 1875 near the junction of Newgate Street and Pepper Street.

Medieval

Formerly named "Fleshmongers Lane" - the name "Newgate Street" was transferred from what became Park Street. Another "Fleshers'" or "Fleshmongers'" Row ran westwards to Goss (Goose) Street; beyond that the undercrofts and galleries at Booth Mansion (nos. 28–34) in Watergate Street and at nos. 38–42 show that it continued at least to Crook Street, if not to Trinity Street. Retailing was a major activity within the city from the earlier 13th century, taking place not only at the stalls set up at markets and fairs, but in permanent premises already called 'shops' (shopae). The shops were generally small, sometimes little more than a lock-up 3 metres by 2 metres, and at most the size of the ground floor of a modest plot, say 8.5 metres by 2.5 metres. By the earlier 14th century such structures were found not just in the four main streets, but in many of the lesser ones, including Castle Street, Pepper Street, Parsons Lane (later Princess Street), Fleshmongers Lane (later Newgate Street), and St. John's Lane.

It would be wrong to think that Fleshmongers Lane remained a shambles of butcher's shops for long. The messuage and cellar known as le Melhouse (meal-house, a corn-merchant) recorded in 1354 stood on the corner of Fleshmongers Lane. The property was leased to a descendant of the citizen licenced to import corn from Ireland in 1316 and from other parts of England in the 1320's. Goldsmith's congregated in Fleshmonger's Lane. Three were named among the taxpayers in 1463, including silversmith Roger of the influential Warmingham family (Thomas Warmingham was still renting there in 1722). Pewterers also operated in this quarter. Henry Port (mercer), William Heywood (cook) and George Bulkley all held civil office in the 1470's and 1480's and each lived in Fleshmonger's Lane, evidently a fashionable address. Gentry families owned property their, including the Duttons and the Savages, and the Norris's aquired three "halls" (aulas) in 1464.

17-18th Cent

During the 17th Century Fleshmongers Lane remained prosperous and the city records show much activity. A carriage house was leased to a Robert Hill and, after his death assigned to the Tailor's Company (it was demolished in 1631 prior to the construction of a new Newgate (the present Wolfgate). During the Civil War there was much damage to buildings in Newgate Street, with the destruction of houses belonging to William Gamul and John Werden, both prominent citizens.

The Lavaux Map shows "Mr Kenrick's House", and the trials and tribulations of the builder who constructed it and his eventual bankruptcy and confinement to debtor's prison are recorded in some detail on the Virtual Stroll website.

The Talbot, an inn which stood in Fleshmonger's Lane, was sold in 1787 and its premises merged with the new and grander Royal Hotel built next door in 1784 and later acquired by Earl Grosvenor.

19th Cent

Newgate Street was the home to Surveyors, at times the Chester Courant (a newspaper) and other "service industries". George Angelo Bell lived there. Batenham, writing in 1827 (when Newgate Street terminated next to the present Grosvenor Hotel - then the Royal Hotel) states:

- "Newgate street on the right is a quiet genteel street having a large and commodious building at the corner called the Royal Hotel with an excellent spacious assembly room attached sixty eight feet long and thirty four feet wide. In this noble room large dining parties are frequently accommodated and it is also often engaged for public concerts. A very Superior subscription news room besides forms part of this extensive establishment"

20th Cent

Eventually, with the construction of the Grosvenor Shopping Center, much of Newgate Street dissappeared under a multi-storey car park and modern shops. Now only a short remnant remains and the surviving buildings of any interest are in part dominated by "brutalist" 1960's "design".

Architecture

The multi-storey car park offers a brutal frontage to the street, detracting from some pleasant historic buildings in what is now a very poor setting and almost concealing a listed ex-church. Fortunately the car-park is screened from Pepper Street by "Newgate House" a reasonably well-designed, brick-built office block errected between the wars. To the Architectural Historian Newgate Street is a fascinating clash of styles, whereas many would pass it by without a second glance.

The Church

Ex-church, now bar. Built 1860, by JW and J Hay, and James Harrison and modified 1884 by Kelly and Edwards. This church is in ashlar yellow sandstone and English garden wall bond brown brick, partly rendered with purple-grey slate roofs. The stone-fronted entrance is offset south of the body of the church, which has a reversed liturgical orientation. The entrance front is in C13 style. There is a double plinth and double boarded doors on ornate hinges in an archway with colonnettes, foliar capitals and ballflowers. There ia a lancet to the left of the entrance. The twin 2-light windows above the entrance have trefoil and quatrefoil tracery. Thre is a quatrefoil window in the gable. The octagonal belfry on the left has a stone spire, and there is a pinnacle to the right. The sides of the entrance and the body of the church are brick, slate-roofed. The sides of the church are simply expressed, that to north having 5 triple lancets. The liturgical west end has 5 lancets, the central one taller than the others; the liturgical east end has a rose window with stone tracery, of 1860; the body of the church was rebuilt in 1884. Internally the church has 5 bays. Cast-iron columns carry arch-braced trusses. Each bay has triple clerestory lancets above former aisles with lean-to roofs. The rose window has patterned stained glass.

- The Church on Wikipedia;

Former Council Electricity Office

The former City Council Electric Headquarters has been converted into restaurant premises, but retains many of the "electrical" symbolds which adorned the building. Around the arched doorway are stone carvings of various transformers, generators, motors and even a glass-jar type wet-cell. Some of the ironwork is decorated with lighning flashes or sparks. The city council opposed private applications to supply electricity to Chester under the Electric Lighting Act of 1882, and in 1889 decided to apply for powers itself. Having obtained authority by an Act of 1890 it then delayed even beginning to implement it until 1892 and hesitated over the choice of a system and a site for the generators until its hand was forced in 1895 by the threat of a rival scheme headed by the duke of Westminster. In 1896 the council opened a coal-fired generating station in New Crane Street, mains were laid along the principal streets in the city centre, and electricity supply began. The number of customers rose from 211 in 1898 to 703 in 1903. In 1904 the city appointed Sydney Ernest Britton as its electrical engineer; he held the post until his death in 1946 and became a leading figure in his profession.

The New Crane Street works reached capacity in 1910 and work started the next year on a hydroelectric generating station on the site of the Dee Mills. The choice of Gothic detailing for the building, consciously in keeping with the architecture of the adjoining Dee Bridge, was influenced by the Chester Archaeological Society. When it opened in 1913 it provided 40 per cent of Chester's electricity at a fifth of the price of coal-generated power. Rising demand from many more consumers meant that its output met only 2 per cent of requirements by 1946, and the hydroelectric plant was closed in 1951, the building being used thereafter as a water pumping station. After the First World War Chester bought electricity from the government's munitions works at Queensferry (Flints.), and in 1923 acquired the power station itself. The overhead high-tension cables between Queensferry and Chester were among the first in the country.

From 1932 the city was buying electricity from the Central Electricity Board's embryonic national grid in order to cope with demand which grew to over 23,000 consumers by 1946, most rapidly in the decade 1927–37. Many of those customers were outside the city. Sydney Britton pioneered rural electrification in the 1920s, especially for dairy farmers, obtaining powers to supply Hoole and parts of Chester and Tarvin rural districts in 1923, with an extension in 1927 to cover 144 square miles. At the third "World Power Conference" (1936) Britton is reported to have said that the farmers around Chester were so advanced that they even used electricity to heat their pig-styes. On the other hand, the council declined to implement his schemes for Chester to participate in a joint electricity authority for south Cheshire and north Wales (1920–3; it went ahead without the city) and to build a new power station at Queensferry (1937).

At nationalization in 1948 the corporation's system came under the Merseyside and North Wales Electricity Board (Manweb), which in 1968–70 built its administrative headquarters in Sealand Road. The buildings had as their centrepiece a seven-storeyed Y-plan office block which dominated the skyline looking west from the city centre until it was demolished in the 1990s.

Number 23

This modest cottage, now an office is probably early C18, but has been altered. It is constructed of Flemish bond brown brick with a grey slate roof. With two storeys of one bay, the first storey has a 2-panel door, south and a 1-pane shop window, both replaced. There is a three-course second storey floorband. The two replaced flush horned sashes have painted stone sills and wedge lintels with false keystones. There is a three-course band beneath a brick parapet with plain painted stone coping. A chimney is behind the main ridge. The wing behind has, like the main block, a ridge parallel with the front, a north gable chimney and modest windows.

Number 21 (Plumber's Arms)

This three-storey pub is brick built with a white stucco covering on the upper storeys, probably late 18th century. The ground floor has a wooden window and door-case with decorative carvings (grapes and hops), and a herringbone brick infill below the window. Above are two wood-cased sash windows - one on each floor and a pediment. The pediment is inscribed "The Plumbers Arms".

Number 19

This town house, later an office and now (2025) a hotel, probably dates from c1770. It is constructed of Flemish bond brown brick with a grey slate roof (not visible at front). With three storeys of one bay, it has a painted stone plinth, three stone steps to a replaced door of 6 fielded panels in case with an architrave and pulvinated frieze to glazed open pediment. There are replaced recessed horned 12-pane sashes. The second storey sillband, is broken at the centre. The second storey has replaced, recessed, horned 12-pane sashes. The third storey has a central, replaced, recessed horned 9-pane sash with a painted stone sill. The windows have rusticated wedge lintels, except for the third storey with false keystones. The painted stone cornice is beneath a brick parapet with a painted stone coping. The parapet to the south end conceals the roof. There are two lateral chimneys. The rear has a flush 4-pane sash to each storey and a rear wing with a door and a small-pane window in its south side, a dual 16-pane second storey sash and two C20 third storey windows.

15 and 17

These are two town houses converted to one, now offices, built early C18 and altered. It is constructed of orange Flemish bond brick with a grey slate roof, having the ridge at a right angle to front. Over three storeys, with six windows. The first storey is rebuilt in approximately similar style, with double doors of 3 fielded panels in case with pilasters, frieze and cornice; a tripartite small-pane window to each side. The front has boarded loading-doors with a 12-pane overlight. The second storey has 6 replaced 14-pane horned sashes with small recessed sills and flat gauged brick arches with brick keys. Obobe the 3-course third storey floorband are 6 nearly flush 12-pane sashes, the 3 to north replaced and horned, the 3 to south with thick glazing bars of early type. These upper windows ave small recessed sills and gauged brick arches with keys. There is a painted stone cyma cornice and a lateral chimney to each side. The rear, added to in C19, has old brickwork but no visible features of special interest.

2020 Walls Collapse

In 2020 Newgate Street hit the national headlines when a nearby portion of the City Walls collapsed. Work had been progressing on the development of "Luxury Flats" when the walls were somehow undermined and slumped onto the site. Despite what was written in the press, the walls at this point are not Roman but a medieval re-construction, some distance back from the original line of the Roman fortifications (which had themselves collapsed at an earlier date). Ephemeral national press coverage confused Roman, Medieval, Civil War and other restoration in a "blamestorm" of recrimination. The local press were more sensible.