Hugh of Avranches

Hugh (the Wolf, the Fat) (1071-1101: First Earl)

(Kings: William I, William II (Rufus), Henry I)

Summary

Given a Palatine county with the power to make and break any law save treason in return for bankrolling Duke William's Invasion, Hugh built castles in England and made a poor job of invading Wales. He managed to arrange the marriage of his son into the monarchs family, but this was to end in tragedy.

- Parents: Son of Richard Goz, Viscount of Avranches, in the far southwest of Normandy.

- Spouse: Ermentrude of Claremont.

- Children: One legitimate son, Richard of Avranches, who succeeded him. - see below for illegitimate issue.

This article is best read in combination with that on Medieval Chester which discusses Hugh's role on a larger scale, including his support for the later Henry I and his part in the conflict between the sons of William the Conqueror. As with the history all of the Earls of Chester some of the details are questionable given the tendency of later writers to elaborate upon the actual historical events. While Hugh is generally described as the first Earl of Chester he was preceeded by Gherbod the Fleming, possibly only for a matter of months.

Origins

Hugh was born around 1047. His father was Richard Goz (otherwise Le Gotz, or Le Gois) believed to be himself descended from Ansfrid, a Dane. One Hrolf Thurstain apparently followed his Viking uncle Rollo, first Duke of Normandy to Normandy and married Gerlotte de Blois, daughter of Thibaut Count of Blois and Chartres. "Rollo" is a Frankish-Latin name probably taken from the Old Norse name Hrólfr, modern Scandinavian name Rolf. He married Poppa. All that is known of Poppa is that she was a Christian, and the daughter to Berengar of Rennes, the previous lord of "Brittania Nova", which eventually became western Normandy. The third son of Gerlotte was Ansfrid the Dane, first Vicomte of the Hiemois, and father of Ansfrid the second (surnamed Goz) whose son another Turstain (Thurstan, or Toustain) Goz was a great favourite of the then Duke of Normandy, Robert the father of William the Conqueror.

Thurstain accompanied Duke Robert to the middle east and was entrusted to bring back the relics the Duke had obtained from the Patriarch of Jerusalem to present to the Abbey of Cerisi - it is not clear whether any of these relics were later unknowingly sworn upon by Harold. Duke Robert died on the return trip and William became the Duke of Normany at age eight in 1035. Thurstain revolted against the young Duke William in 1041 and as a consequence was exiled, and his lands confiscated and given by the Duke to his mother, Herleve, wife of Herluin de Conteville. Richard Goz, Vicomte d'Avranches, or more properly of the Avranchin, was one of the sons of the revolting Thurstain, by his wife Judith de Montanolier, and appears not only to have avoided being implicated in the rebellion of his father, but obtained a pardon and restoration to the Vicomté of the Hiemois.

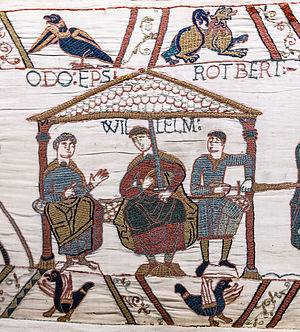

There has been a good deal of historical debate about the familial relationship between Hugh and William. According to tradition Richard Goz strengthened his position at court by securing the hand of Emma de Conteville, who may have been one of the daughters of Herluin and Herleve, and therefore half-sister of Duke William. Some modern historians believe that the evidence for this is insufficient. By this fortunate marriage (if it actually happened) Richard Goz not only recovered the lands forfeited by his father but also acquired much property in the Avranchin. Thus, while many early chronicles state that the later Earl Hugh was the nephew of William the Conqueror, this is at best only in part true as Hugh's mother (Emma) was said to be the child of Robert II's mistress (Herleve) by her later husband (Herluin). However other sources state that this daughter (William's half sister), was called Muriel, and married Guillaume, Seigneur de la Ferté-Macé. Given that Herleve and Herluin married around 1031, their daughter would have been a young bride when she produced their grandson Hugh (he was born in 1047). Herleve and Herluin also produced William's two half-brothers Odo, who may have been born around 1033 and later became Bishop of Bayeux, and Robert (born c.1031), who became Count of Mortain.

Richard's son Hugh d'Avranches had in part bankrolled William's invasion of England (providing either 30 or 60 ships, depending on the source), and probably did not fight at Senlac Hill (called Hastings by some), but was trusted (apparently aged 19) to stay behind and govern Normandy. However, very little is known about his career prior to the Conquest. It is curious that his name is not found in any ducal charters before the Norman Conquest. Hugh's first attestation in a diploma of William the Conqueror with a precise date is from 13 September 1077, confirmed at the dedication of the abbey of Saint-Etienne of Caen. Before that, Hugh appears among the signa of a diploma for Fecamp dating from between 1070-1077/8, which does not mention where it was confirmed.

Earl of Chester

Initially, his holdings in England were limited to Tutbury Castle. This might have been while William the Conqueror was campaigning in the south-west and the north, suppressing the revolt of the earls Edwin and Morcar in England in 1068 with the support of the Welsh. With the convenient departure of Gherbod the Fleming, c.1070, his holdings were greatly extended. Hugh ended up with several manors and lands which had belonged to the Anglo-Saxons and Northumbrians including: Allestrey, Kniveton, Mackworth and Markeaton (all in Derbyshire) from Siward of Northumbria (or Morcar his successor (after the unpopular Tostig)). Avranches also has several connections with the Wirral: see the wiki entry on Saughall Massie for another example.

The historiography of Earl Hugh is particularly interesting and there are several possible reasons for this. First, is his comparatively long life: having been born circa 1047 he lived until 1101. Next is his association with the Palatinate of Chester (a somewhat unique form of administaration), with the Abbey that would become the Cathedral, and with Chester Castle. Third is his association with the Grosvenors who at various times have claimed Hugh as an ancestor or at least a close associate of one. Hugh's actual importance as a magnate on a national scale has perhaps been over-shadowed by his involvement in Welsh conflicts and conquests, but he played an important part in the resolution of the rivalries between the sons of William the Conqueror and the rise from relative obscurity of the youngest, who was to become Henry I. A further factor in the construction of his reputation is what seems to be a sometimes disproportionate interest by historians (both English and Welsh) in the history of all things Cestrian, as well as a tendency for the Gentry of Cheshire to become somewhat fixated in tracing their history back to the Norman Conquest. Earl Hugh was a colourful character, but needs to be seen in a wider context than simply as "a fat man from Chester who invaded Wales".

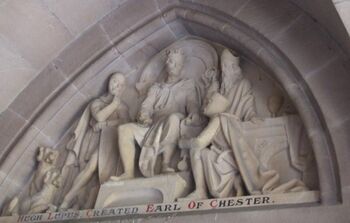

One of the common myths about Hugh is that he was the first of the Earls of Chester, forgetting entirely about the rather unfortunate Gherbod the Fleming (q.v). Many popular histories of Chester fail to mention Gherbod at all, and in many cases depictions of the Earls place Hugh as the first. The stained-glass in the Town Hall at Chester is an exception, but the depictions of the coats-of-arms of the Earls on the Suspension Bridge at Chester and the carved figures on the lodge in Grosvenor Park all place Hugh as the first Earl. Even the Encyclopedia Britannica sometimes lists him as the first Earl and omits Gherbod.

Getting Hugh's history confused started very early. Writing of the year 1072, Matthew of Westminster (who probably didn't exist) recounts the story of Hugh completely wrong, confusing Hugh with Ranulf de Meschines who he calls "Ranulph of Micenis":

- In the same year, king William invaded Scotland with a great army, and Malcolm, king of Scotland, came peaceably to Berwick to meet him, and became his subject. At this time, count Ranulph of Micenis governed the earldom of Carlisle, who had given efficacious assistance to king William in his conquest of England. He began to build the city of Carlisle, and to strengthen the citizens with many privileges. But when king William was returning from Scotland through Cumberland, seeing so royal a city, he took it from count Ranulph, and gave him instead of it the earldom of Chester, which was endowed with many honours and privileges.

The error is easily explained by noting that the "king William" who invaded Scotland was William Rufus, who did so in 1092, and Carlisle was already in existence at the time. 1072 (when Hugh was still earl) has simply been accidentally transcribed for 1092, and the chronicle omits to mention that it was Henry I who gave the Earldom of Chester to Ranulph, but not until 1121.

Tennant was of opinion that the Conqueror himself invested Earl Hugh in the year 1069, for he was then in Chester "repelling the Welsh" and finally reducing Mercia. William Camden (1551-1623) makes it clear that Hugh's powers were, at least in Camden's view, very far reaching:

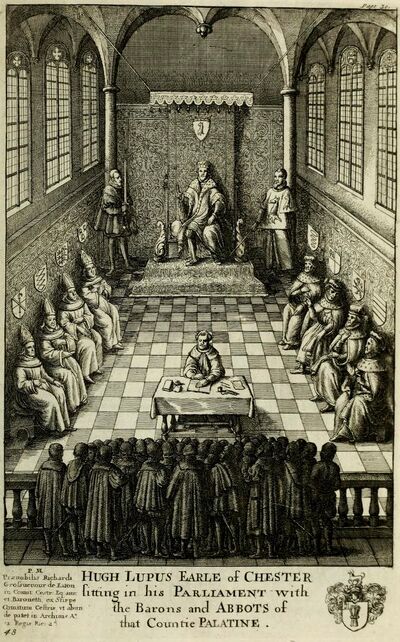

- By Virtue of this Grant, Cheshire enjoyed all Sovereign Jurisdiction within its own precincts And that in so high a degree that the ancient Earls had Parliaments of their own. Barons and Tenants and were not obliged by the English Acts of Parliament. These high and otherwise unaccountable Jurisdictions were thought necessary upon the Marches and borders of the Kingdom as investing the governors of those provinces with Dictatorial Power and enabling them more effectually to subdue the common enemies of the Nation. And agreeable to these high powers when the style in all legal proceedings of the Courts at Westminster ran "Contra Coronam et Dignitatem Regis", in our County Palatine these pleas were constantly expressed "Contra Dignitatem Gladii Cestris".

Foote Gower/Thomas Falconer add:

- This famous Sword of Dignity is still remaining in the British Museum. It is in length about four feet and so unweildy as to be brandimed with great difficulty by a very strong man with both his hands The blade is two edged and has this inscription immediately beneath the hilt Hugo Comes Cestris.

The sword does not appear to be on public display at the British Museum, and the length of the sword would seem to indicate that if it ever did exist it was a ceremonial rather than a practical weapon. These are just some of the minor errors in the historical record of Hugh, chosen here not to denigrate the historians but to illustrate how the picture of the real Hugh has become somewhat blurred over the years.

The Palatinate

As noted above the Palatinate has been said to have been granted special political rights and an almost unique governance model. However the view of this has also changed somewhat since it was current in Victorian times. Early writers such as Ormerod (1785–1873) were concerned with the development of the county at a manorial level and Ormerod simply appears to have accepted the view of William Dugdale (1605-1686) and John Leyland (1503-1552) as to the status of the Norman Earls: effectively that they were the absolute rulers of the Palatine save that they had to be loyal to the English king, and that the Palatinate was effectively not a part of England but a quite separate political body. Ormerod even uses an illustration from William Dugdale's "Monasticon Anglicanum" in this context (see below). This supposedly shows the Earl's "parliament" with his lords spiritual and temporal (barons and abbots) sitting down the sides. Above the heads of each is a coat of arms, which gives perhaps a first clue that Dugdale is not being entirely accurate as arms were unlikely to have been used at the time (see: Chester Heraldry Tour) and many were later restrospectively "attributed".

The issues over the particular nature of the Palatinate were first brought into sharper focus (see links below) in 1951 by Geoffrey Baraclough (1908-1984) and have since been the subject of considerable debate amongst historians. Barraclough challenged the view that the Palatinate was created shortly after the Norman Conquest for Earl Hugh, and argued that it only really came into existence under Ranulf de Blondeville who was Earl from 1181-1232. His argument was essentially that the strength of the Earls of Chester was not originally based on special rights or status, but on their wealth and influence, and that the Palatinate jurisdiction did not fully emerge until after the Earldom was permanently annexed by the Crown in 1237. It has been argued that there is no historical basis for Camden's statement (given above) that "Cheshire enjoyed all Sovereign Jurisdiction" at the time of Earl Hugh. For example it appears that the "pleas of the sword" were never mentioned before Ranulf's charter of 1215-16 and it therefore appears that Camden simply assumed that what was true in the time of Ranulf was true in the time of Hugh. It is clear that there were indeed certain limits on what Earl Hugh could do, most significantly as regards the church. The Domesday Book makes it evident that the bishop of Chester, based at St Johns held his lands not from Earl Hugh but directly from the king, and that might have been a factor in why Hugh chose to found his own religious foundation (see: Cathedral for a further discussion).

It has been argued that the independence of Chester was required by reasons of it having a proximity to Wales and having been established as a bastion against Welsh incursions, but no such special status was required by the other Marcher counties and earldoms, such as Shrewsbury and Hereford. Also, Robert of Rhuddlan who was appointed Hugh's "commander of troops" held land to the west of the Clwyd from the king and not from Hugh. Indeed, Robert was responsible for much of the conquest in North Wales which was conducted in the name of the king rather than expanding the Palatinate. Until quite late in the career of the Norman Earls their charters were not exceptional in structure or form and differ in no significant way from those granted by other earls. The Earls did attempt to expand their holdings, but often this was based on lands elsewhere in England which were not part of the Palatinate but held separately, at times from different rulers in England and Normandy. These pages on the non-royal Earls will hopefully illustrate how the structure of the Palatinate evolved over time.

Politics

The Norman Conquest was not simply a matter of turing up at Hastings and defeating Harold. It was a rather messy business during which resistance continued for some time and there was much in-fighting between factions as well as involvement of the Welsh and the Scandinavians. There was also considerable conflict amongst the Conqueror's own sons. A lesser king than William might have misplayed his hand, but he managed to achieve a somewhat precarious balance by careful appointments to positions of power, by diplomacy and by military action. Hugh of Avranches now appears to have played a much more significant part in national and international events than as portrayed by Victorian and some later historians, and especially by the writers of some local guidebooks, which sometimes appear to confine his story to events in Wales. In fact, Hugh's activities in England and Normandy are in many ways more interesting than what he did in Wales and somewhat less well known and understood. In a fairly short space of time Hugh managed to become almost as powerful as the king without ever openly engaging in a direct confrontation with the Crown.

By 1075 and the subjugation of the Revolt of the Earls, the Conquest was completed. Hugh may have been involved with a plot hatched by William's scheming half-brother Bishop Odo in 1082. According to Orderic Vitalis, Odo had heard a prediction, by "certain sorcerers at Rome", that a prelate of his name would become pope - there being a conflict between Gregory VII and Henry IV at the time. This conflict was a variant on the usual argument between the church and the state as to the right to appoint bishops and indeed other churchmen. Henry IV kicked off the dispute in 1075 with a letter starting with one of the least diplomatic openings ever:

- "Henry, king not through usurpation but through the holy ordination of God, to Hildebrand, at present not pope but false monk..."

The letter called for the election of a new pope, and ends, "I, Henry, king by the grace of God, with all of my Bishops, say to you, come down, come down!", and is often quoted with "and to be damned throughout the ages", which is actually a later addition. By 1084 the matter had resulted in a seige of Rome with Clement III installed as pope (or antipope) and Gregory VII still resisting a few hundred yards away from the basilica in the Castel Sant'Angelo. Gregory called on his allies for help, and Robert Guiscard (the Norman ruler of Sicily, Apulia, and Calabria) responded, entering Rome on 27 May 1084 after a seige. The Normans came in force and attacked with such strength that Henry and his army fled. Gregory VII was rescued, but Rome was plundered in the process, for which the citizens of Rome blamed Gregory. As a result, Gregory VII was forced to leave Rome under the protection of the Normans, fleeing eventually to Salerno, where he grew ill and died on 25 May 1085. The Normans then arranged the election a new pope (Victor III) while Clement III was now in Ravenna and still claiming to be pope.

Historian William Lambarde (1536-1601) wrote much later of Odo that:

- "the king was offended by the disobedience, avarice and ambition of Odo who raked together great masses of gold and treasure., Odo then caused the gold to be ground into small powder, filled into pots and had them sunk in the bottom of rrivers so that he could eventuslly purchase the papacy of Rome!"

According to the usually accurate Orderic, Odo bought a palace in Rome and bribed "senators". He prepared to go there, in the company of "a goodly company of distinguished knights" and Earl Hugh of Chester. Vitalis remains unclear about the precise motivations of this expedition and the role of Hugh, but the Papacy does seem to have been "up for grabs" at the time. In 1082, when Odo's downfall came, Rome and the Vatican were already under seige by Henry IV, but the Vatican had not yet been seized. It is possible that Odo had become convinced that he could replace Gregory VII. King William heard of the plan and, sailing from Normandy, intercepted Odo in the Isle of Wight, where he was fortunately delayed by the weather. There were attendant complications as William's relationship with Gregory was not simple, but there were also the consequences of a conflict between the Holy Roman Emperor and William's half brother. William ordered that Odo be arrested but Odo protested that no-one could lay a hand on him because he was a bishop and could only be judged by the pope, so William had him arrested not as the Bishop of Bayeux but as the Earl of Kent.

Whatever was going on, Odo was imprisoned by William for years and was only released as William lay dying. There is some tangental evidence that Hugh had some kind of rupture with William at around this time as while he appears in a good number of William's charters in the years before 1080, Hugh vanishes from the charters between 1080 and 1082, possibly indicating that he had thrown in his lot with Odo. However, apart from some land in Normandy (Hugh held estates within Odo's Bishopric of Bayeux) there appears to be little connection between the two men. The solution appears to be that Hugh was highly adept at chosing the eventual winner, but also hedging his bets and also being careful to avoid supporting those who were least likely to be of use to him due to the location of his estates. By either luck or foresight Hugh seems to have had a knack for picking winners with possibly the sole exception of Odo.

William the Conqueror dies

William the Conqueror died on 9 September 1087. Accounts of his death vary. In one, William led an expedition against the French Vexin in July 1087. While seizing Mantes, William either fell ill or was injured by the pommel of his saddle when his horse stepped onto some hot debris. William of Malmesbury, a contemporary of Orderic Vitalis, adds in his Gesta Regum Anglorum that William, his somewhat corpulent stomach protruding over the forward part of his saddle, was injured when he was thrown against the pommel and his internal organs ruptured. William retreated and returned to his capital at Rouen. His condition continued to worsen and, mindful of the afterlife to come, he "gave way to repeated sighs and groans". The funeral was something of a farce, with the tomb being too small and the body already beginning to decompose so that an attempt was made to cram the bloated William into his sarcophagus. As Orderic wrote: "the swollen bowels burst, and an intolerable stench assailed the nostrils of the by-standers and the whole crowd".

William left Normandy to Robert Curthose - his eldest son - and the custody of England was given to William's second surviving son, William Rufus, on the assumption that he would become king. The youngest son, Henry, received only money. The division of the kingdom was bound to lead to difficulties as some nobles would have held land both in England and in Normandy and thus could be placed in a difficult position as regards loyalty should the two rulers clash. This would soon be the case, and to a great extent the history of the next few hundred years would be influenced by the fact that barons would owe allegience to different overlords for the various parts of their holdings and would have to choose sides in case of war and risk losing the land held from the king these chose not to support.

Of the two elder sons Robert was considered to be much the weaker and was generally preferred by those nobles who held lands on both sides of the English Channel since they could more easily circumvent his authority. Robert was also useless when it came to money. He quickly exhausted his inherited wealth and at one point he was so poor that he had to remain in bed due to a lack of clothes. William Rufus was the more capable. Henry was almost completely sidelined at this point. Hugh also appeared to side with Wiliam Rufus in 1091 when William and Robert plotted to deprive their younger brother Henry of his lands. Henry had appealed to Hugh for help, but weighing up the relative strengths of the forces involved, publicly sided with Rufus and declared his castles for the king. However Hugh also had some advice for young Henry and suggested that he take up a defensive position at Mont Saint-Michel. Henry was soon besieged on the island fortress and hung-on while his brothers quarrelled. He finally reached a surrender deal which saved his life but drove him into impoverished exile. At times during the next years Henry drops out of the records completely although he was probably assisted by Earl Hugh. He finally resurfaces in Domfront and soon became one of William Rufus' most capable commanders.

In 1094 Hugh assisted William Rufus in the defence of Normandy against the French king (Philip the Amourous). As recorded in the AS Chronicle:

- There was the King of France through cunning turned aside; and so afterwards all the army dispersed. In the midst of these things the King William sent after his brother Henry, who was in the castle at Damfront; but because he could not go through Normandy with security, he sent ships after him, and Hugh, Earl of Chester.

In 1095, another conspiracy against William Rufus occurred in England led by Robert of Mowbray, earl of Northumberland. This time, again, Hugh kept on good terms with William Rufus. In 1096, Robert Curthose made a bargain and left Normandy in the hands of William Rufus to join the First Crusade. Finally William Rufus could, in a sense, reconstruct his father's Anglo-Norman state.

The circumstances of the death of William Rufus in 1100 are suspicious, especially given the death of Robert's son Richard in similar circumstances just a few months before. Historians are still somewhat divided on whether "hunting accidents" are the expected results of a dangerous sport (and probably alcohol) or a convenient way of disposing of someone. By this time Earl Hugh of Chester was approaching the end of his life and was probably quite ill. His son and heir was a minor and so did not have to choose sides in the contest between Robert and Henry. His support of Henry I had placed the Conqueror's youngest and probably most capable son on the throne.

Baronies

When appointed to the Palatinate Earl Hugh was quick to employ his rights to call conventions of landholders to assist him in his council and to make decrees from which there was no appeal to the king. More importantly he created several hereditary feudal baronies. In England baronies were generally the highest degree of feudal land tenure with the rank of Baron being the tennant-in-chief under the king. A barony would comprise several manors. English feudal baronies (and all lesser forms of feudal tenure) were abolished by the Tenures Abolition Act 1660, but the titles/dignities remain.

The baronies of Cheshire were distinct in that they were created by the Earl and are an early marker for the existence of the Palatinate as a distinct form of government. English Earls were initially an Anglo-Saxon institution. The title originates in the Old English word eorl, meaning "a man of noble birth or rank". The word is cognate with the Scandinavian form jarl, and meant "chieftain", particularly a chieftain set to rule a territory in a king's stead (and name). Wessex was Shired by the 9th century, and the Shire system was extended to the rest of England as the Kings of Wessex unified the country. Each Shire was governed by an Ealdorman.

By around 1014, English shires or counties were grouped into Earldoms, each was led by a local great man, called an earl; the same man could be earl of several shires. When the Normans conquered England, they continued to appoint earls, but not for all counties; the administrative head of the county became the sheriff. There were no Dukes made between the reigns of William the Conqueror and Henry II; those kings were themselves Dukes in France. When Edward III of England declared himself King of France, he made his sons Dukes, to distinguish them from other noblemen, much as Royal Dukes are now distinguished from other Dukes. Later Kings created Marquesses and Viscounts to make finer gradations of honour: an earl is a member of the peerage, ranking below a marquess and above a viscount.

In Cheshire the barons were appointed by the Earl. Hugh's first barons were:

- Eustace of Mold, Baron of Hawarden, Flint, Hereditary Steward;

- Nigel of Cotentin, Baron of Halton Hereditary Constable and Marshal, whose descendants took the name de Lacy and became Earls of Lincoln in 1232;

- William Malbank, Baron of Nantwich;

- Robert FitzHugh, Baron of Malpas, supposedly the illegitimate son of Earl Hugh (if this is true then he became a monk) - was succeeded in the Earl's lifetime by David le Clerk de Malpas, alias Egerton, ancestor of the Egerton Family;

- Hamon de Massey, Baron of Dunham-Massey, owner of the manors of Agden, Baguley, Bowdon, Dunham, Hale and Little Bollington, taking over from the Saxon thegn Aelfward according to the Domesday Book;

- Richard de Vernon, Baron of Shipbrook;

- Gilbert de Venables, Baron of Kinderton.

The descent of these baronies needs to be seen through the lens of much later events in Cheshire, where the local gentry became almost obsessed with their possible descent from the Normans. This led to long-running disputes such as that between Sir Thomas Mainwaring and Sir Peter Leycester as regards whether Earl of Chester Hugh de Kevelioc was the legitimate father of a daughter called Amicia. The dispute involved the eminent antiquarian William Dugdale (12 September 1605 – 10 February 1686) and was connected with what seems to have been a particular local interest in family history which in part manifested in heraldry. There was also a conflict over the rights to be engaged with the preparation of so-called "funerary memorial boards" between Dugdale and the local "herald" Randle Holme.

This strong interest in family history was further fired by George Ormerod and his noted work "The history of the county palatine and city of Chester... incorporated with a republication of King's Vale Royal and Leycester's Cheshire antiquities", which is largely concerned with the local "peerage" of Cheshire. The extent to which these later works and associated disputes have modified views of Hugh has not yet been fully explored, but may be why Hugh is often seen in the light of local history rather than his broader role in Norman society.

Asyla

Earl Hugh established three "asyla" in Cheshire. These were at Hoole Heath near Chester, Overmarsh near Farndon and Rud Heath near Middlewich. These were places to which a felon from any place in England (or Wales) could flee and seek the protection of the Earl. The sanctuary at Hoole Heath may well be the reason for the bad reputation of Newton Hollows attributed to Lucian the Monk. Hemingway describes them as follows:

- These sanctuaries were the source of much emolument to the earls, who received fines from all such persons when they came to reside under their protection a heriot at their death and in case of their dying without issue claimed their goods and chattels.

Thus we see that the tale of criminals being free if they escaped the "hue and cry" and reached Chester is only partly true. Much later, in the times of Edward II, they were described as follows:

- By an inquisition taken before Hugh de Audelith Justice of Chester on Sunday after the feast of St Peter ad Vincula it was found That a certain large piece of Waste called Overmarsh was in ancient times ordained for strangers of what country soever and assigned to such as came to the peace of the Earl of Chester or to his aid resorting there to form dwellings but without building any fixed houses by the means of nails or pins save only booths and tents to live in.

In in the reign of Edward III:

- The jury declare upon their oaths that the Moor which is called Rudheath was formerly a waste place very anciently assigned and set apart by some of the old Earls of Chester for the reception not of their own subjects but of all fugitive strangers coming to the aid of the Earl's peace either from England or from any other countries And there is an inquisition of the same tenor relative to the other of Hoole Heath.

Interestingly, Hoole is not mentioned in Domesday (see: Parishes for a further discussion). Various theories have been put forward for the origin of its name, among which is a reference to "hovels" or "huts". It is possible, but by no means proven, that Hoole came into existence from one of the Asyla, possibly through Welsh refugees.

The existence of these Asyla implies that Cheshire was to some extent outside of the English legal system, but the issue as to whether it was fully outside appears never to have been tested by any sufficiently notorious felon trying to make use of them. Hugh is also supposed to be the origin of a rule that during fairs held in the city no felon (presumably from elsewhere) could be arrested except for crimes committed at the fair - although this may be a myth. The beginning and end of the fairs was indicated by the suspension and removal of a glove on the south side of St Peter's church (see Gloverstone) but this may not have meant that the "hand of justice" was completely suspended just that the markets would not be subject to the special monopolies held by the "freemen" of Chester.

War with the Welsh

Hugh did have some misadventures in Wales with Gruffydd ap Cynan - who, despite having been imprisoned for some years at Chester Castle - outlived Hugh (who died in 1101) and lasted until 1137. However, wars with the Welsh were only to be expected:

- Hugh Lupus, Earl of Chester, and William Fitz Osborne, Earl of Hereford, all of whom were near relations to king William, were by him entrusted with the care and government of the western parts of the island, in order to secure them against the incursions and depredations of the Welsh, who frequently plundered these people, and were likely to be very troublesome, as were afterwards found to be by many of their descendants.

The opinion of historians has varied as to whether the primary role of the "Marcher Lords" was to defend England from the Welsh, or facillitate the expansion of Norman influence into Wales. In this latter regard the Normans were assisted by internal strife amongst the Welsh. Unusually for a Welsh king or prince, a near-contemporary biography of Hugh's adversary Gruffudd, "The history of Gruffudd ap Cynan", has survived. Much of our knowledge of Gruffudd comes from this source and it has been an influence on how Hugh is remembered. Gruffudd was the son of a Welsh prince, Cynan ap Iago, who was a claimant to the kingship of Gwynedd but was probably never its king, though his father, Gruffudd's grandfather, Iago ab Idwal ap Meurig, had ruled Gwynedd from 1023 to 1039. Gruffydd was raised in Ireland being of part Viking stock and appears in his first bid for the Welsh throne to have first sought the assistance of the Normans who were seemingly happy to appear to be helpful.

Gruffudd landed in Angelsey in 1075 and then travelled to:

- ... the castle of Rhuddlan to Robert of Rhuddlan, a renowned, valiant baron of strength, a nephew of Hugh earl of Chester, and he besought him for help against his enemies who were in possession of his patrimony. And when Robert heard who he was, and for what he had come, and what his request was, he promised to support him. ('History of Gruffudd ap Cynan')

The alliance with the Norman did not last and soon everyone was fighting everyone else. Hugh fought one major battle near modern day Abergely -

- Hugh Lupus, on his march to invade the Isle of Anglesey, passing through the defile of Cevn Ogo, which is the narrowest pass on this part of the coast, was attacked by an armed band of Welshmen, which had been posted there to intercept his progress, and of which, after an obstinate and protracted battle, 1100 were left dead on the spot.

It has been said that at no place in Wales has more blood been shed than in the defile of Cevn Ogo - otherwise known as the "Field of Corpses". Harold II fought Grufydd ab Llewelyn, Prince of North Wales, on the plain near Cevn Ogo, and, after a sanguinary battle, was driven back to Rhuddlan. In the reign of Henry II, Owain Gwynedd fortified himself in this pass, where he gave battle to the forces of that monarch, and repulsed them with great slaughter. It is also said that near the same pass, Richard II was surrounded and conducted to Flint Castle, where he was treacherously betrayed. It is now a caravan park.

The Magic Stone

Hugh appears in many local "folk tales". Many of these begin to fall-apart if examined in detail. For example Gerald of Wales has the following to say about "Hugh" and Angelsey:

- "As many things within this island are worthy of remark, I shall not think it superfluous to make mention of some of them. There is a stone here resembling a human thigh, which possesses this innate virtue, that whatever distance it may be carried, it returns, of its own accord, the following night, as has often been experienced by the inhabitants. Hugh, earl of Chester, in the reign of king Henry I., having by force occupied this island and the adjacent country, heard of the miraculous power of this stone, and, for the purpose of trial, ordered it to be fastened, with strong iron chains, to one of a larger size, and to be thrown into the sea. On the following morning, however, according to custom, it was found in its original position, on which account the earl issued a public edict, that no one, from that time, should presume to move the stone from its place. A countryman, also, to try the powers of this stone, fastened it to his thigh, which immediately became putrid, and the stone returned to its original situation."

Of course the problem here is that the Hugh of King Henry's time is possibly not the same Hugh who invaded Wales with Shrewsbury (in 1098). In fact it is difficult to see who exactly Gerald means. Hugh was earl from from 1071-1101, and Henry I was king from 1100 until 1135, so either this even happened in the last year of the earls life or Gerald has his facts wrong. Gerald does record many very unlikely tales which can make him an entertaining but sometimes difficult source. As for the later history of the stone it was identified by folklorist Walter Gill (1876–1963) as the "Maen Morddwyd" ("The Thigh Stone"), built into the wall of the ruined church of St Nidan (now a private chapel) next to Llanidan House in south-western Anglesey. Thomas Pennant, who reported on a visit to the House in the 1770s, stated that Gerald's stone was built into the church. By 1849 the church was at least partly destroyed and it isn't entirely clear what happened to the stone. Gerald also gives a masked hint that the stone was a pagan relic:

- Dicitur etiam quod si venereum opus in loco eodem vel prope fieri contigerit, sicut aliquoties probatum est, statim lapis guttis magnis desudabit. Similiter etiam si procacitatem ibidem vir et mulier exercuerint. Ex venere quoque ibidem expleta nunquam genitura provenit. Unde et ob hoc, casula deserta penitus qu‚ ibidem olim esse solebat, tantum muro lapideo fatalem hodie lapidem videas circuiri.. (It is said also that if the "work of Venus" takes place in the same place or nearby it will happen, as is proved a number of times, at once the stone will sweat great drops. Similarly, in addition, if a man and woman practice acts leading to degradation in that very place. Out of the congress actually finished in that place, at no time has any one going to bear a child born one. From which, and on account of this, the small hut, deserted inside, which was formerly customarily there in that place, only by a fated/deadly wall of rock the stone you may see encircled.)

These pagan connections may explain why the antiquarian Henry Rowlands, who was the local vicar, never mentioned the stone. References to the rock as "shaped like a thigh-bone" may actually be something of a euphemism.

What is more certain is that in 1088 Hugh took over lands in North Wales and rebuilt the castle at Rhuddlan where he based the somewhat over zealous cousin..

- Robert of Rhuddlan, who, in 1088, encamped a considerable army near its walls. In the same year, Grufydd ab Cynan is said to have entered the Conway with three ships, and, landing under the castle at high water, to have left his vessels on shore at the recess of the tide, and proceeded to ravage the neighbouring country. Returning from his predatory incursion, and driving before him a large booty of men and cattle towards his ships, Robert, who witnessed the spectacle with indignation, descended from his fortress, attended only by a single soldier, and without any defensive armour but his shield. The Welsh attacked him with missiles, and, having filled his shield so full of darts that it fell under the weight, rushed upon him in a body, and striking off his head, fastened it to the mast of one of their ships, and sailed away in triumph.

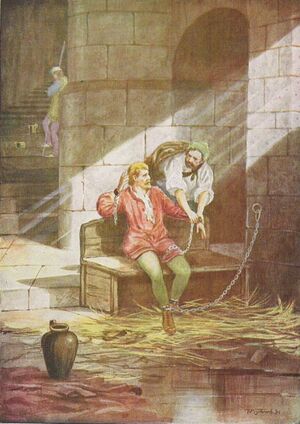

Gruffydd was captured in 1081 (as noted, there is a conflict of dates here! - some place the death of Robert at Deganwy in 1093 - which makes more sense) when he was enticed to a meeting with Hugh Earl of Chester and Earl of Shrewsbury (probably Roger) at Rug, near Corwen. According to his biographer this was by the treachery of one of his own men, Meirion Goch. Gruffydd was imprisoned at Chester Castle for many years (some say ten, others 12, others 16):

- ... put him in the gaol of Chester, the worst of prisons, with shackles upon him, for twelve years (History of Gruffudd ap Cynan)

- And straightway after he had been captured, Earl Hugh came to his territory with a multitude of forces, and built castles and strongholds after the manner of the French, and became lord over the land (History of Gruffudd ap Cynan)

In his effort to consolidate control over Gwynedd, Earl Hugh of Chester forced the election of Hervé the Breton upon the Bangor diocese in 1092, with Hervé's consecration as Bishop of Bangor performed by Thomas of Bayeux, then Archbishop of York. It was hoped that placing a prelate loyal to the Normans over the traditionally independent Welsh Church would help pacify the local inhabitants. However, the Welsh parishioners would have none of it and remained hostile to Hervé's appointment. The Norman bishop was forced to carry a sword with him and rely on a contingent of Norman knights for his protection. Hervé did not help matters by routinely excommunicating parishioners who he perceived as challenging his spiritual and temporal authority. The 12th-century Liber Eliensis described the situation as follows:

- "Since they [the Welsh] did not show the respect and reverence due to a bishop, he [Hervey] wielded the sharp two-edged sword to subdue them, constraining them both with repeated excommunications and with the host of his kinsmen and other followers. They resisted him nonetheless and pressed him with such dangers that they killed his brother and intended to deal with him the same way, if they could lay hands on him."

The point of all this is that many tales exist of the times of Gruffudd and Hugh which appear to recount events in some detail, but may well have been innocently embroidered by later writers.

One rather obvious question is why Hugh did not simply have Gruffydd killed, blinded or otherwise mutilated. One reason is that the Normans, in spite of their generally negative reputation, did not go in for the kind of extreme political violence that was routinely used in England before the Conquest, and that re-emerged around the year 1300. The Normans were extremely bloody in their warfare, but not in their politics. after 1066. "No man dared slay another", said the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in its obituary of William the Conqueror in 1087, "no matter what evil the other might have done him." During William's reign, only one nobleman was executed - Waltheof, Earl of Northumbria. Waltheof was implicated in a rebellion against the new king in 1075, and though he speedily confessed and turned himself in, he paid the price the following year, when he was beheaded on a hill just outside the walls of Winchester. Quite why William felt he had to make an example of Waltheof is unclear, but the fact remains he is the exception that proves the new rule. After his execution in 1076, no earl was executed in England until 1306, when Edward I commanded the death of the Earl of Atholl. Even he was executed on a gallows 30 feet higher than ordinary, to signify his higher status than his fellow prisoners. The same was only true to a lesser extent of lower ranks of the nobility. Henry I met an invading French army under Louis VI at Brémule in the Norman Vexin. The battle was a resounding victory for the Anglo-Normans, yet of the 900 or so knights engaged, only three were killed. Orderic Vitalis wrote:

- "They were all clad in mail and spared each other on both sides, out of fear of God and fellowship in arms (notitia contubernii); they were more concerned to capture than kill the fugitives. As Christian soldiers, they did not thirst for the blood of their brothers, but rejoiced in a just victory given by God for the good of Holy Church and the peace of the faithful."

Of course, bedside Orderic's wish to present Henry's conduct of a "just war", there was also ransom to be had, and the same would mostly not have applied if the enemy were Welsh and Irish. Another factor which may have been important is that the Normans were very inter-related and the payment of a ransom could have avoided long running feuds or vendetta's.

Revolt in Wales

Hugh lost Anglesey and much of the rest of Gwynedd in the Welsh revolt of 1094, led by Gruffydd ap Cynan, who had escaped from captivity at Chester. By late 1095 the uprising had spread to many parts of Wales. This induced the then king William II of England (William Rufus) to intervene, invading northern Wales in 1095. The personal involvement of the English king in a North Welsh conflict being somewhat rare at the time. However Rufus' army was unable to bring the Welsh to battle and returned to Chester without having achieved very much. Once again, this particular campaign seems to have been noted for it's violence:

- Hugh Lupus, Earl of Chester, while carrying on his desolating warfare against the Welsh, landed his forces at Cadnant, in the parish, in 1096, and, having encamped on the summit of an eminence called Dinas, at the upper extremity of the vale, commenced a series of devastations, which were characterized by the most barbarous and atrocious outrages.

Just why he should camp at "Dinas" in 1096 on first glance presents something of a mystery as Hugh would appear to have had a perfectly good castle at Aberlleiniog established in 1088. However, the castle was captured and burnt to the ground by when Gruffydd escaped imprisonment at Chester. The present stone-built castle was constructed by a colourful 17th century character called Thomas Cheadle, the constable of Beaumaris. Following a long feud which ended in a duel Cheadle's son was tried for murder, found guilty and executed by public hanging in Chester (others say at Conwy).

Prisoners taken by the Earls of Chester and Shrewsbury, were apparently executed at Cae Grogi, or Marian Crogwydd, a field situated about three quarters of a mile westward from Penmon Priory. Local legend held that two holes sunk in the limestone rock, still visible until recently, were the slots made to hold the gallows. Hugh stood loyally by William Rufus in the rebellion of 1096 - and was perhaps a little over zealous as he was charged, with having barbarously blinded and mutilated (by castration) his brother-in-law, William Comte d'Eu, who had been taken prisoner in the uprising. King Willam mounted a second invasion of Wales in 1097, but again without much success.

A possible side effect of these attempts to conquer north Wales was the transfer of the north-west Mercian see in 1075 from Lichfield to St Johns, Chester. One possible reason for the move was that the new Norman bishop, Peter, may have seen prospects for diocesan expansion in north Wales (there was then no neighbouring bishop at St. Asaph and Peter may have felt that if large territories in north-east Wales were to come under his jurisdiction, Chester would be a more central base than Lichfield. However, in 1098, the next Norman attempt to conquer north Wales suffered a severe setback. Florence of Worcester records that, in 1098, Hugh of Chester and Hugh de Montgommery Earl of Shrewsbury led troops into Anglesey and their furious 'victory celebrations' which followed were exceptionally violent, with rape and carnage committed by the Norman army left unchecked. The earl of Shrewsbury had an elderly priest mutilated, and "made the church of Llandyfrydog a kennel for his dogs". Gerald of Wales tells the story of what happened next, in 1098 (the church he mentions is probably St Tyfrydog Church in Llandyfrydog):

- There is also in this island the church of St. Tefredaucus, into which Hugh, earl of Shrewsbury, (who, together with the earl of Chester, had forcibly entered Anglesey), on a certain night put some dogs, which on the following morning were found mad, and he himself died within a month; for some pirates, from the Orcades, having entered the port of the island in their long vessels, the earl, apprised of their approach, boldly met them, rushing into the sea upon a spirited horse. The commander of the expedition, Magnus, standing on the prow of the foremost ship, aimed an arrow at him; and, although the earl was completely equipped in a coat of mail, and guarded in every part of his body except his eyes, the unlucky weapon struck his right eye, and, entering his brain, he fell a lifeless corpse into the sea. The victor, seeing him in this state, proudly and exultingly exclaimed, in the Danish tongue, "Leit loup," let him leap; and from this time the power of the English ceased in Anglesey.

Here Gerald refers to the military campaign in the summer of 1098 when Earl Hugh joined with Hugh of Montgomery (2nd Earl of Shrewsbury) in an attempt to recover his losses in Gwynedd. Gruffydd ap Cynan had retreated to Anglesey, but then was forced to flee to Ireland when a fleet he had hired from the Danish settlement in Ireland changed sides. The "Pirates" were a Norwegian fleet under the command of King Magnus III of Norway, also known as "Magnus Barefoot", who attacked the Norman forces near the eastern end of the Menai Straits. With Magnus was Harold Haraldson - said to be the postumous son of Harold Godwinson, who was born at Chester around December 1066. Hugh of Shrewsbury was killed by an arrow (said to have been shot by Magnus himself). The Saga of Magnus Barefoot actually mentions "Hugh the Stout":

- Afterwards King Magnus sailed to Wales; and when he came to the sound of Anglesey there came against him an army from Wales, which was led by two earls -- Hugo the brave, and Hugo the Stout. They began immediately to give battle, and there was a severe conflict. King Magnus shot with the bow; but Huge the Brave was all over in armour, so that nothing was bare about him excepting one eye. King Magnus let fly an arrow at him, as also did a Halogaland man who was beside the king. They both shot at once. The one shaft hit the nose-screen of the helmet, which was bent by it to one side, and the other arrow hit the earl's eye, and went through his head; and that was found to be the king's.

The Normans were thus obliged to evacuate Anglesey, and the following year (1099) Gruffydd ap Cynan returned from Ireland to take possession again. Hugh apparently made an agreement with Gruffydd and did not again try to recover these lands, which makes it difficult to see how Hugh could have been in Angelsey during the reign of Henry I.

Before his death in 1101, Hugh had made a huge fortune from his position as the Earl of Chester and also became so fat that he could hardly walk (he was known in later life as "Hugh the Fat"). Orderic Vitalis states that Hugh was "a slave to gluttony, he staggered under a mountain of fat" and was "given over to carnal lusts and had a numerous progeny of sons and daughters by his concubines". The Welsh called him Hugh Flaidd (Hugh the Wolf or Hugh Lupus) and a wolf's head appears on his arms. In an 1086 engraving of the coat of arms the artist has gave the head of the wolf a wide grin, which might be mistaken for that of a cat - this has been suggested as the origin of the Cheshire Cat. As regards Hugh, Hemingway quotes the following:

- He was, "saith Ordericus, not only liberal, but profuse; he did not carry a family with him, but an army. He kept no account of receipts or disbursements. He was perpetually wasting his estates; and was much fonder of falconers and huntsmen, than of cultivators of land, and holy men , and by his gluttony he grew so excessively fat, that he could hardly crawl about.

Orderic is not entirely accurate when he writes that Hugh kept no accounts as by 1094 he had probably established a chamberlain who was responsible for finance, although the chamberlain first appears as a witness to a charter which may be in part fraudulent. This role later became part of the separate Exchequer at Chester.

There are quite a few relics of the age of early Norman activity in Wales and on the border which can still be visited today, although some are much altered. Besides Chester Castle, a further castle was build at Frodsham although nothing of this now remains above the ground. Another castle was built at Shotwick to defend the important fords over the Dee and again little remains to be seen today. Hugh is also credited with the construction of Aberlleiniog Castle, on Angelsey. For further information on some of these see Cheshire Castles.

Hugh and the Abbey

Another of Hugh's contributions to the history of Chester was his establishment of a Benedictine Abbey. This was not his only involvement with the church, during his lifetime, he founded the Benedictine Abbey of Sainte-Marie-et-Saint-Sever, Saint-Sever-Calvados, Normandy and gave significant land endowments to Whitby Abbey, North Yorkshire.

In 1092, af Hugh's third invitation Anselm of Bec came from France to England to found the Benedictine Abbey at Chester, which would later become the Cathedral. Alselm had spent some time in Avranches in 1060 before entering the abbey of Bec as a novice - and it is possible that he met Hugh then. The Chester Annales record the foundation thus:

- In hoc anno venit dompnus Anselmus abbas Ecclesiæ Beccensis Angliam qui sepius ante venerat in Angliam, veniens itaque tunc Angliam Anselmus a multis acclamatus archiepiscopus, quitanti honoris onus humiliter fugiens, rogatu nobilis principis, comitis Hugonis Cestriam venit, ibique abbatiam in honorem Sanctæ Werburgæ fundavit, et monachis ibidem congregatis Ricardum monachum Beccensem primum abbatem instituit. Quo facto, in eodem anno in reditu suo a Cestria, archiepiscopus Cantuariensis factus est. (1093 In this year the lord Anselm, abbot of the church of Bec, came to England, who before this had frequently been in England. On his coming to England this last time, Anselm was acclaimed by many as archbishop, but, humbly desiring to escape the burden of so great an honour, on the invitation of the noble prince, earl Hugh, he came to Chester, and there founded the abbey in honour of S. Werburg, and, having assembled the monks together, he appointed Richard, a monk of Bec, the first abbot. Having done this, in the same year, upon his return from Chester, he was made archbishop of Canterbury.)

In reality the situation was rather more complex. When about to return to Bec, Anselm was refused permission by the then king (William Rufus) but the following year, when the king fell ill (and believed himself dying) Anselm was nominated to the then vacant see of Canterbury. The reluctant Anselm was finally consecrated as Archbishop of Canterbury in 1093 (this was a disaster for William as the two did not get on). From an early period the monks of St. Werburgh's claimed that Earl Hugh I had granted them the right to hold a fair on the three days around the feast of St. Werburgh's translation on 21 June. Robert of Torigny's "De Immutatione Ordinis Monachorum" records that "Hugo vicecomitis Abrincatensis postea…comes Cestrensis" also founded "abbatiam Sancti Severi in Constantinensi episcopatu" - Saint-Sever in Normandy. Although it has been suggested that Hugh became a monk at St Werburgh in Chester, four days before he died (1101), the Chester Annales simply records his death:

- Defuncto Hugone comite cestrensi principe nobili. Ricardus puer vij annorum comitatum suscepit (1101 The noble prince Hugh, earl of Chester, being dead, Richard, a boy of seven years of age, inherited the earldom.)

There is a "slight" problem with the charter of Abbey, which like many such documents goes to great lengths to ensure that the grant is perpetual and cannot be reversed later. The charter ends:

- "Et ut hc omnia essent rata et stabilia in perpetuum, ego Come Hugo et mei Barones confirmavim us (&c.), ita quod singuli nostrum propria manu, in testimonium posteris signum in modum Cruc is facerunt:"

..and is signed by earl Hugh himself; Richard of Avranches (his son); Hervey, bishop of Bangor ; Ranulf de Meschines (his nephew, who eventually inherited the earldom); Roger Bigod; Alan de Perci; William Constabular (William FitzNeil - Baron of Halton); Ranulph Dapifer; William Malbanc (Baron of Nantwich}; Robert FitzHugh (Baron of Malpas); Hugh FitzNorman; Hamo de Masci (Baron of Dunham-Massey); and Bigod de Loges. The little problem is that the charter cannot date from 1093 and be signed by Richard of Avranches (who was only seven years old in 1101). This problem is solved if the charter is dated later than 1093 and merely confirms the earlier grant - but then the problem arises that Robert FitzHugh may have been dead by then. However it should be remembered that mediaeval monks were known to fake charters at times.

Children

Hugh married Ermentrude of Claremont the daughter of Hugh I, Count of Clermont-en-Beauvaisis, by whom he had one son, Richard of Avranches, who succeeded him. Richard married Lucia-Mahaut of Blois, daughter of Stephen Count of Blois and sister of another Stephen of Blois (the future King Stephen). Richard's mother in law was Adela, a daughter of William the Conqueror and hence sister to both William Rufus and Henry I. Both Hugh's son Richard and Richard's wife died in the White Ship disaster (1120). Earl Hugh had at least three [known] illegitimate children by unknown mistresses:

- Otuel: also drowned with the loss of the White Ship (25 Nov 1120) - a note in the text of Florence of Worcester names "Ricardus comes Cestrensis, Otthuel frater eius" among those drowned in the sinking of the White Ship. He was tutor to the children of Henry I King of England.

- Robert: recorded as the son of Hugh Earl of Chester by Orderic Vitalis, he became a monk at the abbey of Saint-Evroul, Normandy. He was appointed Abbot of Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk in 1100 by Henry I King of England, but deposed in 1102 by Anselm Archbishop of Canterbury at the Council of London.

- Geva, who was possibly the same who married Geofrey Ridel of Drayton Basset in Staffordshire. Orderic Vitalis records that Ridel died in 1120 in the shipwreck of the White Ship. “Geva, filia Hugonis comitis Cestriæ, uxor Galfridi Ridelli” survived her husband and later founded Canwell Priory, with the consent of “Ranulfi comitis Cestriæ cognate mei…hæredum meorum… Gaufridi Ridelli et Radulfi Basset”, by undated charter.

Despite having illegitimate children of his own Hugh seems to have strong ideas about fidelity, given the fate of William of Eu. Orderic Vitalis records that:

- "..the king caused him to be deprived of sight and emasculated. This punishment was inflicted on him at the suggestion of Hugh, earl of Chester, whose sister he married, but was unfaithful to her having since the marriage had three children by a concubine."

A footnote by the translator of Orderic suggests that the mutillation was "the result of the insulted wife's vengance".

Exhumed

In 1724 the remains of Hugh Lupus were "discovered" in Chester Cathedral, wrapped in leather, and deposited in a stone coffin, having a cross on the breast. They were re-buried with the following terrible verse:

- Altho my corpse it lies in grave

- And that my flesh consumed be,

- My picture here, now that you have

- An Earl some time of this city

The 'Other' Hugh Lupus

Hugh Lupus Grosvenor, 1st Duke of Westminster KG (13 October 1825 – 22 December 1899) was the son of Richard Grosvenor, 2nd Marquess of Westminster and Lady Elizabeth Mary Leveson-Gower. He was created Duke of Westminster on 27 February 1874, the most recent person neither born into nor related by marriage to the British Royal Family to be advanced to the highest degree of the peerage. He had succeeded as 3rd Marquess of Westminster and 4th Earl Grosvenor in 1869. By the time of his elevation the family's London property in Mayfair, Belgravia and Pimlico had made it the richest family in the United Kingdom. He had his main country seat, Eaton Hall in Cheshire, reconstructed at enormous expense. He was one of the most successful British race horse owners of all time - the character "Colonel Ross" in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's short story Silver Blaze is believed to be based on Hugh Grosvenor.

The Grosvenor family crest is now a variation on a blue shield with a golden sheaf (garb) of corn on it (in proper heraldic terms that is 'azure, a garb or'). However an earlier heraldic device used by the family was 'a shield blazoned Azure, a Bend Or' (that is a blue shield with a yellow (gold) diagonal stripe).

Unfortunately, in 1385, while Richard II of England was busy invading Scotland two of his knights realized that they were using the same coat of arms. Sir Richard Scrope from Bolton in Yorkshire (and Chancellor of the Exchequer) and Sir Robert Grosvenor from Cheshire were both bearing blue shields with the gold stripe. Scrope brought an action (Scrope v. Grosvenor (1389)), and Grosvenor maintained his ancestor had come to England with William the Conqueror bearing these arms. The case was brought before a military court and presided over by the constable of England - and the first sitting of the Court of Chivalry in the which decided the Scrope/Grosvenor Armorial Bearings was held at St Johns Church. Several hundred witnesses were heard and these included John of Gaunt, King of Castile and Duke of Lancaster, Geoffrey Chaucer and a then largely unknown Welshman called Owain Glyndŵr. The witnesses for Grosvenor stated that:

- ..it was generally reputed in the counties bordering on North Wales that his ancestors had borne the arms azure a bend or from the time of Sir Gilbert de Grosvenor a follower of Hugh Lupus Earl of Chester who was nephew to the Conqueror and that the said arms were to be seen in windows and on tombstones in several churches of Cheshire

The Abbot of the Cistercian Abbey Vale Royal spoke still more positively to the pedigree and arms of Grosvenor saying expressly:

- ..that he has it from chronicles and ancient writings in his monastery that Sir Robert Grosvenor descended in direct line from Gilbert le Grosvenor who in the train of his uncle Hugh Lupus came over with the Conqueror armed in the said arms which he used to the time of his death

In 1389 the case was finally decided in Scrope’s favor - but Grosvenor was allowed to continue bearing the arms within a silver border. Neither party was happy with the decision, and in 1390 Richard II decided these shields were too similar for unrelated families in the same country to bear. Grosvenor switched to the blue shield with the golden sheaf of corn.

The sheaf of corn is interesting, because it first appears in English heraldry on the arms of Hugh de Kevelioc a later Earl of Chester who was infamous for revolting against the king, and was also used by his son Ranulf de Blondeville (a rather more noble knight).

There is another interesting connection between the Grosvenors and the Earls of Chester. The Forests of Mara and Mondrem together formed one of the three hunting forests of the Earls of Chester, the others being the Forests of Macclesfield and Wirral. It was created by Hugh d'Avranches, a keen huntsman, soon after he became Earl of Chester, although the area might have been an Anglo-Saxon hunting forest before the Norman Conquest. "Forest", in this context, means an area outside the common law and subject to forest law; it does not imply that the area was entirely wooded, and the land remained largely in private ownership. Hugh de Kevelioc is said to have granted his manor of Budworth together with a half share interest in the forestership of Mara (which included Delamere Forest) to Robert Grosvenor at some time in the 1150s. The bounds of Grosvenor's bailiwick were described in 1361 as being:

- 'from Stanford Bridge along the King's highway as far as Northwich, thence following the bounds of the forest as far as the Darley Brook, and thence following the Darley Brook as far as the bounds of Rushton, and then following the bounds of Rushton and Olton as far as Yemelegh Mill and from the mill following the bounds between Eaton and Alpraham as far as the town of Tarporley and then following the bounds of the said forest as far as Stanford Bridge'.

Being born in 1147, Hugh de Kevelioc would have been a minor at the time and one wonders just how real the grant of the forestership was!

Robert Grosvenor's claim to a family link to the Original Hugh Lupus has been the subject of much debate. There are several problems with the claim, not least of which being that given the young age of the original Hugh Lupus at the time of the Norman Conquest nephew "Gilbert" (who seems to be mentioned nowhere else) would have had to be remarkably young at the time of the invasion and it is surprising that this is not recorded. The name "Venour" does turn up in the records at Battle Abbey and this has been suggested as a possible indication that "Gilbert (gros) Venour" (Gilbert the fat hunter) might have existed - although it is unlikely he was Hugh's nephew. Whatever the truth, by 1825 the Grosvenor's decided it was time to name a member of the family after their supposed "ancestor".

Curiously, claiming ancestry to the Norman Earls of Chester was not a new thing amonst the Cheshire gentry. The same had been tried by the Mainwarings. The Mainwaring's argument was that Hugh de Kevelioc had a younger daughter (Amicia) by a first wife prior to the four sisters of Ranulf de Blondeville. It was through these sisters that various royal lineages passed, so what Mainwaring was effectively doing was giving himself a semi-royal pedigree, in much the same way that Hugh de Kevelioc may have tried to do, possibly by creating the legends of Harold and Emperor Henry's survival. Grosvenor simply hopped back to an earlier Earl to claim an even "better" pedigree.

Hugh in Fiction

Perhaps the most common fictional tale about the original Hugh Lupus is that he tortured and killed a young gypsy boy for poaching on his land and afterwards was the subject of a curse "that no son would follow father in the succession to the earldom". Hugh was of course succeed by his son, who admittedly died before he had an heir, but the succession of the Norman Earls was not particularly troubled by the curse. The actual fame of what has since become known as the "Grosvenor Curse" appears to have only arisen in relatively modern times with particular reference to events following the death in 1909 of the then 4 year old son of the 2nd Duke, as even though the 2nd Duke married several times, he never sired another son.

In the Chester Pageant of 1910 a rather feeble but dissolute Earl Hugh appears as part of a recreation of his founding of the abbey. Hugh is ill and is cured by the intervention of Anselm of Bec. Curiously, the same story of illness and a cure by Anselm has been attached to both William Rufus and Earl Hugh. As the episode is set in 1093, Hugh is still eight years from the end of his life and in 1093 would have been aged about 52, whereas the pageant appears too place him much closer to death. In fact Hugh will engage in further warfare in Wales in the following years. In the Chester Pageant 1937 a quite different version of Hugh is portrayed only a brief mention is made of the supposed illness of Hugh portrayed in the previous pageant and there does not appear to be a miracle cure by Anselm.

As noted at various places in the text above, Hugh makes several appearanced in public art in Chester, both as statuary (St Werburgh Street, Northgate Street, Eaton Hall and at the Town Hall), and in Stained Glass, often associated with his heraldic emblem of the wolf. There is also a carving of John Canmore in St Werburgh Street and all of the Earls appear in Grosvenor Park.

Sources and Links

Related Pages

- The Grosvenors:

Online Sources

- THE EARLDOM AND COUNTY PALATINE OF CHESTER: Barraclough's 1951 paper;

- Arthur Jones (1910). The history of Gruffydd ap Cynan: the Welsh text with translation, introduction and notes. Manchester University Press. . Translation online at The Celtic Literature Collective;

- Killing or Clemency?: Ransom, Chivalry and Changing Attitudes to Defeated Opponents in Britain and Northern France, 7-12th centuries;

- Lewis, C. P. (1991): The formation of the Honor of Chester, 1066-1100

Chronicles

Book Sources

- B. M. C. Husain (1973). Cheshire ubder the Norman Earls: A history of Cheshire Volume 4

- Tony Bostock (2021). The Norman Earls of Chester & Their Barons

- D. Crook (1991). "Central England and the Revolt of the Earls". Historical Research. 64:403-10;

- Mike Ibeji, Treachery of the Earls, by Mike Ibeji, from "BBC History of the Normans";

- Edward Augustus Freeman (1901). A Short History of the Norman Conquest of England. Page 113-114;

- Simon Evans (1990). A Mediaeval Prince of Wales: the Life of Gruffudd Ap Cynan. Llanerch Enterprises. ISBN 0-947992-58-8.;

- K.L. Maund (ed) (1996). Gruffudd ap Cynan : a collaborative biography. Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-389-5;

- Kari Maund (ed) (2006). The Welsh kings: warriors, warlords and princes. Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-2973-6;

- Paul Russell (ed) (2006). Vita Griffini Filii Conani: The Medieval Latin Life of Gruffudd Ap Cynan. University of Wales Press. ISBN 0-7083-1893-2;

Other Links

These are only a small selection of the many references to Hugh on the WWW. Please note that the information on the internet (including on the ChesterWiki site!) may not be accurate (especially on sites about people's supposed ancestors!)