Ormerod

Life

George Ormerod was born (1785) in Manchester and educated first privately, then briefly at the King's School, Chester, before continuing his education privately again under Rev Thomas Bancroft, vicar of Bolton. His interest in family history may well have been fueled by the fact that his father, of whom he was the only son, had died some 13 days before he was born.

He matriculated at Brasenose College, Oxford, in 1803, graduated BA in 1806 and received the honorary degree of MA in 1807. He inherited extensive estates in Tyldesley and south Lancashire. In 1808, he married Sarah Latham, the daughter of John Latham (1761–1843), a doctor living in Bradwall Hall, Sandbach. Following their marriage they first lived in Rawtenstall but moved to Great Missenden the following year. In 1810 he was the tenant at Damhouse in Astley.

He became involved with research into the history of Cheshire and to make this task easier he bought Chorlton Hall and estate, which was four miles from Chester. He lived in this house from 1811 to 1823. Early in life Ormerod showed a taste for heraldry and topography. About 1808 he began to make large collections for the history of Cheshire. In Chester Castle he discovered an immense number of original documents, and he subsequently examined in the British Museum the Randle Holme' copious collections, which proved to be not very accurate abstracts of the Chester Castle records. A valuable loan of books and documents was also made to him by Hugh Cholmondeley, dean of Chester, whose sympathy and aid Ormerod warmly acknowledged. From 1813 to 1819 he was almost exclusively occupied in writing his ‘History’ and seeing it through the press. When his historical work was completed he moved to Gloucestershire, buying the Barnesville estate at Sedbury which he renamed Sedbury Park. He lived there from 1828 until his death in 1873. Offa's Dyke ran across the park, of his new house and Ormerod personally traced it through what he believed to be its whole course.

Ormerod was the father of ten children and one of his daughters, Eleanor Anne Ormerod, was a noted biologist. He was elected F.S.A. on 16 Feb. 1809 and F.R.S. on 25 Feb. 1819. He was also fellow of the Geological Society. He gradually became blind in his later years and died at Sedbury Park on 9 Oct. 1873. His library was sold in 1875.

Works

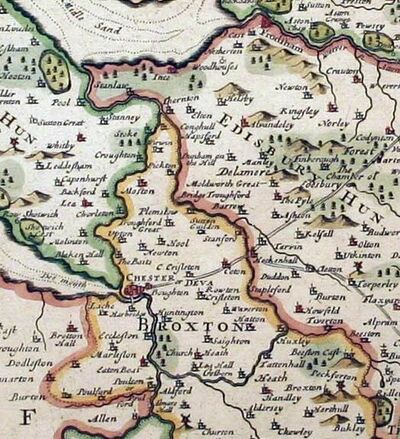

The full title of his major work is "The history of the county palatine and city of Chester... incorporated with a republication of King's Vale Royal and Leycester's Cheshire antiquities". An extremely rare initial print in two volumes with duplicated plates was followed by a general subscription in ten parts, which formed three volumes, between 1816 and 1819. Much of his research was from documents held in Chester Castle. He also relied on documents collected by William Cowper. Ormerod himself only wrote between a quarter and a third of the book, the rest being simply copied from earlier works and records, including the work of Daniel King.

Like other county histories of the period, the work consists mainly of family history, manorial history and antiquarian topography. He deliberately excluded reference to commerce, industry and urbanisation. The has been some speculation as to exactly why Ormerod spent so much time on his work. Proposed reasons include that he was schooled not to leave a task uncompleted, that he had his own interest in the past possibly due to his predeceased father, and that he wished to ingratiate himself with the Cheshire gentry. He was certainly already well connected and had independent wealth, so he really did not need the income. One additional reason may have been the family history of his wife (or, at first, wife to be), Sarah Latham of Bradwall Hall and of the families who had lived in the Manor of Bradwall. At the time of their courtship another geneologist was trying to prove an association with the manor, and it may just be that Ormerod actually started the work as a result of his blossoming relationship.

The first edition of his most famous work is, unfortunately, full of errors, especially as regards the family trees which make up a large part of it. It is therefore prudent always to check information given in Ormerod against a second source whenever possible. Some of the errors are corrected in later editions of his work. Despite this, he is an excellent starting point and often indicates where there are issues with his sources.

Ormerod is also very weak on geophysical features: his discription of the course of the river Gowy bears only a passing resemblance to the actual route taken and contains some obviously improbable assertions. Ormerod cites a very peculiar version of the course of the Gowy, with it actually dividing the Wirral from the rest of Cheshire by flowing into both the Dee (as Flookersbrook) via the Backford Gap and into the Mersey:

- "That, therefore, which they call the Gowy, hath his head not far from Bunbury, and runneth north-west by Beeston Castle, to Teerton and Huxley, where it divideth itself into two parts ; one goeth west to Tattenhall, Gosburn, Lea Hall, and at Aldford falleth into the Dee. The other part goeth northwards to Stapleford, Hocknel-plat, and Barrow (where it taketh in a brook that Cometh from Tarporley and Tarvin), and so passeth to Plemstow-bridge, Trafford, Picton, and Thornton, where it divideth itself again into two parts; one of which keepeth its course north-west to Stanley, Stanney, and Poole, and afterwards falleth into the Marsey. The other part goeth south-west to Stoke, Croughton, Chorlton, the Baits, and so falleth into the Dee, hard by Chester, being there called Flooker's-brook, and divideth Wirral from the rest of Cheshire; and therefore some imagine that it is called Wirral."

Evidently Ormerod made no attempt to verify the course of a river that was almost on his own doorstep. However, he does recognise that there are issues with the route of the watercourse and understands that the construction of the Wirral Line of the Chester Canal has modified the landscape. It is worth remembering that geology was not as well understood in Ormerod's day as it is in present times.

Other Historical "blunders"

Ormerod's early history of Cheshire, dating from just before 1816 contains some statements which are, in the light of modern knowledge, quite wrong, but he may often have had some reason for making them. On balance perhaps, it is sometimes better to have a complete list of possible sources than having a historian filter materials. Also, he needs to be read in the context of Georgian Chester and the perceptions he would have had of the history in his own time. Where his history is quoted what is often taken as fact is what what Ormerod only considers as opinion.

Some examples are:

Æthelwulf at Chester

Ormerod appears to be the main conduit for the often quoted reference to a "witan" being held at Chester in 837 where Æthelwulf, King of Wessex, son of Ecgbert recieved the homage of rulers "from Berwick to Kent". This was apparently based on the chronicle of Peter Langtoft, which was written in the 13th century. The reality of this meeting and the existence of any related political arrangements or consequences is a moot point, and sometimes it appears that Ormerod is happy to mention just about any connection between Cheshire and wider history, which could introduce spurious associations. On the other hand, it illustrates the wide scope of his research.

Vikings camp on Hoole Heath

Ormerod takes some information from Bradshaw and apparently confuses himself utterly:

- In 894, according to Henry Bradshaw, Harold king of the Danes, Mancolin king of the Scots, and another confederate prince, encamped on Hoole Heath, near Chester, and after a long siege reduced the city, but soon afterwards were attacked by Alfred, who pursued thither their comrades who had fled from Buttingdune. The time and the success of the siege by Alfred are variously related by the historians, but the result appears to be that the Danes left the city in consequence of famine

Reading "between the lines", we see that Ormerod recognises that matters are "variously related by the historians", and that this is "according to Henry Bradshaw".

Bradshaw is known to be a not very accurate historical source (and his Latin treatise "De antiquitate et magnificentia Urbis Cestricie" is lost). In 894 the king of Scotland, or rather Picts/Alba was Domnall mac Causantín. He ruled 889-900. The Chronicle of the Kings of Alba has Donald succeeded by his cousin Constantine II. Donald's son Malcolm (Máel Coluim mac Domnall) was later king as Malcolm I and while he raided England, he never got as far south as Chester. The Battle of Buttington was fought in 893 between a Viking army and an alliance of Anglo-Saxons and Welsh. However it took place either near Welshpool or on the River Wye. The same Vikings (under Hastein) are known to have attacked Chester in 894, but other than Bradshaw no independent source mentions the Scots as being involved at all.

Texts of the works

Sources and links

- George Ormerod on Wikipedia;

- Eleanor Ormerod, his daughter;

- Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 42;

- John Hess on Ormerod;