Palatinate

"Cheshire" has been described as a "Palatine" county "to which the king's writ did not run" and from which men spoke of "crossing from Cheshire into England". Certainly Cheshire has been viewed as semi-autonomous at times: with no MPs sent to Westminster; its own de facto parliament; its own legal system and its own head of state – at first the Norman Earl and later the king (or his heir) in his capacity as Earl of Chester. It has often been written, that it so from the Norman Conquest. In fact, there is surprisingly little evidence that Cheshire was in any significant way different from other counties in the early Norman period.

Reading some Georgian, Victorian and even later "historians" (including early Chester guidebook writers) gives a somewhat distorted view of the administrative history of Cheshire which may be summarised as follows:

* The Normans arrived and "Hugh Lupus" became Earl of Chester. He was a close relative of William the Conqueror and an ancestor of the Duke of Westminster. Hugh was given virtual independence from the king because the Welsh were so much trouble;

* Hugh became rich (and very fat) by invading Wales, and appointed Barons from whom the leading families of Cheshire are descended;

* Cheshire (and Flintshire) had, from the Norman Conquest, the special status of a "County Palatine" with significant freedom from the national administration;

It is important to note that as with many things in the history of Chester and Cheshire the views of historians have changed significantly on some matters in the last fifty years, modern works based on older literature (this includes some, but not all, guidebooks and web-pages) may be misleading.

In England, Wales and Ireland a county palatine or Palatinate is often understood as an area ruled by a hereditary nobleman enjoying special authority and autonomy from the rest of a kingdom. The name derives from the Latin adjective palātīnus, "relating to the palace", from the noun palātium, "palace". It thus implies the exercise of a quasi-royal prerogative within a county, that is to say, a jurisdiction ruled by an earl, the English equivalent of a count. A duchy palatine is similar but is ruled over by a duke, a nobleman of higher precedence than an earl or count. However the term Palatinate was only used with reference to Chester in and after 1297. It has been suggested that it only came into use by circumstances in the late thirteenth century which saw Edmund of Lancaster marry Blanche of Artois and obtain the honorific title Count Palatine of Champagne, in 1276, although he was governing in the name of his step-daughter. At around this time Chester and Lancaster adopted the title as did Durham. However, accurate information on the origins of the Palatinate is diffficult to find.

According to a very general interpretation, the Palatinate nobleman swore allegiance to the monarch yet had the power to rule the county largely independently of the king. A Palatinate can therefore be distinguished from a feudal barony, held from the king, which possessed no such independent authority. Rulers of counties palatine created their own feudal baronies, to be held directly from them in capite, such as the Barony of Halton. County palatine jurisdictions were created in England under the rule of the Norman dynasty, while in continental Europe they have an earlier date. It is not at all clear that Hugh of Avranches, the later Earls of Chester and later still the county had quite so much independence from England as early antiquaries and Victorian writers assumed.

There were some peculiar features of the Earldom of Chester, in that the crown never at the early stage appointed a sheriff to Cheshire. The sheriff of course was the crown’s regional administrator for financial and legal purposes. "Sheriff" means "Shire Reeve", with "reeve" (Old English: gerefa) being a general term that could refer to a variety of administrative officials. The lack of a sheriff in the county suggests that the earl’s lands lacked royal oversight. However, this situation probably arose because the crown did not hold lands or tenants within the county of Cheshire, and therefore the sheriff would have no lands to administer there for the crown.

Another difference in Cheshire was that the county was also exempt from royal oversight with regard to justice both via the office of sheriff and the new royal legal officer, the Justice/Justicar. The office of sheriff of the city of Chester was first recorded in the 1120s, earlier than in any other English borough. This 12th century sheriff was appointed by the Earl, who was Ranulf de Meschines for most of the 1120's. Indeed in Ranulph I's charter granting jurisdiction over the summer fair to St. Werburgh's abbey, provision was made for the amount received in fines by the monks to be deducted from the farm which the city sheriff rendered to the earl's chamberlains. As the leading citizen of Chester, the sheriff presided over the city court (the Portmote), maintained law and order, and, as noted, accounted to the earl's chamberlains for the revenues of the city. The office of mayor only came into existence later, and at first the mayor was lower in precidence than the sheriff. Cheshire would eventually have its own Justice, but just when this role appeared is not completely clear.

A number of royal charters, grant or confirm the grants made by the earls of Chester to the city of Chester. King Henry II granted the city the rights they had in the time of his father, namely trading rights in Dublin, and King John would later confirm this. Whilst King Henry’s charter may have been granted before Earl Ranulf’s majority and while the honour was in custody, King John’s was definitely not. This has been trailed as evidence to shows control by the Crown and that there was some royal oversight in the county. However, the rights being confirmed relate to trade outside of the county. King Henry III also issued charters inspecting and confirming the grants of Earl Ranulf. While royal courts were not present within the county, and legal supervision was therefore provided through the earl’s court, royal courts could adjudicate the earl’s decisions if they needed to. For example a plea of false judgement made by Earl Ranulf’s court was brought before the court at Westminster and the Regency Council in 1220. Ranulf’s decision was supported and the court at Westminster held that the warrantor should lose his foot.

As for the location of the "palace" of the earl this is also of interest. Both the Braun and Hogenberg map of Chester (from around 1581) and later maps shows "ruin of the house of the count of Chester" by the River Dee in Edgar's Field (also known as "Kettle's Croft" prior to 1892), close to the location of Minerva Shrine. The present day park is named after King Edgar, who in 973, is supposed to have been rowed up the River Dee from there by eight British princes, possibly implying that the location had some importance from an early date. Hemingway writes of it:

- "In a field on the right of Handbridge called Edgar's Field is an ancient piece of sculpture supposed to be intended for the figure of Pallas the Dea armigera of the Romans. The goddess appears in her warlike dress with her bird and altar. Adjoining this figure is a considerable indention in the rock to which tradition has given the name of Edgar's cave. The sculpture is certainly of great antiquity being noticed by Malmesbury who wrote in 1140, by Hoveden in 1192, by Selden, Camden, the Polychronicon, and the Saxon Chronicle and Dr Cowper in a note on his II Penseroso about 1747 says The foundations of his Edgar's princely mansion are now apparent just below Chester bridge southward. Beyond this several centuries ago stood some ancient buildings whose site is marked by certain hollows for says Pennant who wrote about 1778 the ground probably over the vaults gave way and fell in within the remembrance of persons now alive. Tradition calls the spot the site of the palace of Edgar. Nothing is now left from which any judgment can be formed whether it had been a Roman building as Dr Stukeley surmises or Saxon according to the present notion or Norman according to Braun who in his ancient plan of this city styles the ruins then actually existing Ruinosa damns Comitis Cestriensis. Perhaps it might have been used successively by one of them who added or improved according to their respective national modes."

Lucian the Monk mentions a visit to the Earl's residence but his description does not give anything other than the most vague indication of where it was located.

A further complication in the history of the Palatinate arises through the presence of Royal Forests, originally the Earl's forests. These included the Forests of Mara and Mondrem and the Wirral Forest. These were originally in the hands of the Earls before they passed into the hands of the king. The "THE DISAFFORESTATION OF WIRRAL" adds a further level of complexity to the history of the legal administration of the Palatinate.

Mercia, Wessex, Northumbria

To discuss the development of palatinate juristictions and highlight some of the interpretations that have accreted to that at Chester over the centuries it is useful to go back well before the Norman conquest. This helps illustrate two of the main issues relating to the palatinate: firstly, what it actually was and secondly, how it was later described and interpreted.

Durham

The County Palatine of Durham was a jurisdiction in the North of England, within which the bishop of Durham had rights usually exclusive to the monarch. It developed from the Liberty of Durham, which emerged in the Anglo-Saxon period. The gradual acquisition of powers by the bishops led to Durham being recognised as a palatinate by the late thirteenth century, one of several such counties in England during the Middle Ages. The county palatine had its own government and institutions, which broadly mirrored those of the monarch and included several judicial courts. From the sixteenth century the palatine rights of the bishops were gradually reduced, and were finally abolished in 1836. The last palatine institution to survive was the court of chancery, which was abolished in 1972. The County Palatine of Durham emerged from the liberty known variously as the "Liberty of Durham", "Liberty of St Cuthbert's Land", "The lands of St. Cuthbert between Tyne and Tees" or "The Liberty of Haliwerfolc", the latter translates to "district of the holy saint's folk".

Around AD 547, an Angle named Ida founded the kingdom of Bernicia after spotting the defensive potential of a large rock at Bamburgh, upon which many a fortification was thenceforth built. Ida was able to forge, hold and consolidate the kingdom; although the native British tried to take back their land, the Angles triumphed and the kingdom endured. In AD 604, Ida's grandson Æthelfrith forcibly merged Bernicia (ruled from Bamburgh) and Deira (ruled from York, which was known as Eforwic at the time) to create the Kingdom of Northumbria. It was Æthelfrith who would take part in the Battle of Chester in c.616 for reasons that are not at all clear. In time, the realm of Northumbria was expanded, primarily through warfare and conquest; at its height, the kingdom stretched from the River Humber (from which the kingdom drew its name) to the Forth. Eventually, factional fighting and the rejuvenated strength of neighbouring kingdoms, most notably Mercia, led to Northumbria's decline.

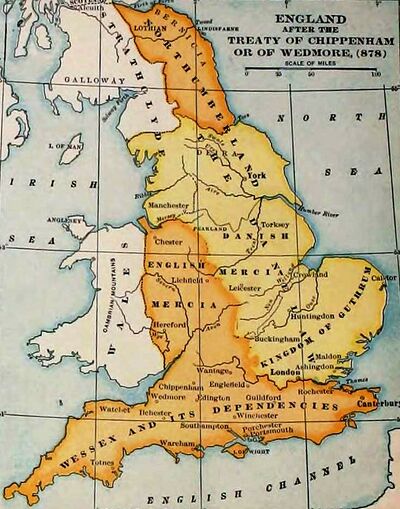

Viking control over the Danelaw, the central belt of Anglo-Saxon territory, resulted in Northumbria becoming isolated from the rest of Anglo-Saxon Britain. Scots invasions in the north pushed the kingdom's northern boundary back to the River Tweed, and the kingdom found itself reduced to a dependent earldom, its boundaries very close to those of modern-day Northumberland and County Durham. The kingdom was annexed into England in AD 954. King Eric I (Bloodaxe) was killed at Stainmore allowing King Eadred to recover York, reuniting Northumbria with that of All England. "High-Reeve" (his actual title is uncertain) Osulf I of Bamburgh was appointed ealdorman ("earl") of Northumbria.

It is not difficult to see how Northumbria could develop an administration and legal system which was distinct from that of the rest of "Anglo-Saxon" England and how this could persist as the County Palatine of Durham. However, in many respects, the Palatinate of Durham was different way to the later Palatinate of Cheshire: for example it's head was a bishop and the succession was not inherited.

Mercia

In the south and midlands the kingdom of Mercia gained supremacy as descibed under Saxon. As discussed in that article at some point the Anglo-Saxons reached Chester bringing with them their language and their version of religion. It seems likely that it was Mercian expansion westward which established the Anglo-Saxons in Chester, rather than Northumbrian expansion southward. The "Mercian Supremacy" refers to the period between c.716 and c.825 (some say 600 to 900), with it's "golden age" being the reign of Offa (757 – 29 July 796), supposed builder of the eponymous dyke which possibly indicates what was at the time the extent of Mercian expansion westwards.

Wessex

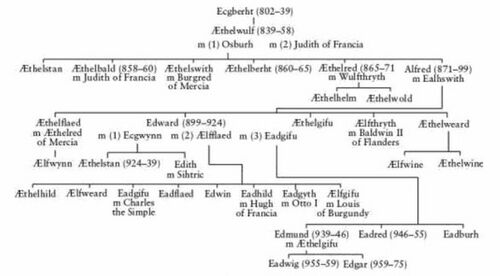

Wessex rose under the House of Ecgbert (c773 – 839: he is depicted in the sculptures at the Town Hall in Chester). Under Ecgbert, Surrey, Sussex, Kent, Essex, and Mercia, along with parts of Dumnonia, were conquered. He also obtained the overlordship of the Northumbrian king. This made him, in the eyes of some Victorian historians, the first king of all England. However, Mercian independence was restored in 830. During the reign of Ecgbert's successor, Æthelwulf, a Danish army arrived in the Thames estuary, but was decisively defeated (851) at the Battle of Aclea by Æthelwulf and his sons, Æthelstan and Æthelbald. What little is known of this battle is in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle:

- "three and a half hundred ships came into the mouth of the Thames and stormed Canterbury and London and put to flight Beorhtwulf, King of Mercia with his army, and then went south over the Thames into Surrey and King Æthelwulf and his son Æthelbald with the West Saxon army fought against them at Aclea, and there made the greatest slaughter of a heathen raiding-army that we have heard tell of up to the present day, and there took the victory."

When Æthelwulf's son, Æthelbald, usurped the throne, the kingdom of Wessex was divided to avoid war. Æthelwulf was succeeded in turn by his four sons, the youngest being Alfred the Great.

Vikings had been raiding across the North Sea since at least the 790's, but in 865 the Great Heathen Army arrived and aimed to conquer and occupy the four kingdoms of East Anglia, Northumbria, Mercia and Wessex. Alfred ("the Great") managed to stop them in something that was more stalemate than defeat, but Mercia was effectively cut in two, with "English Mercia" surviving south of Watling Street and the "Danelaw" existing to the north. Although the term Danelaw was not used until the 11th century England was still largely divided between powers based in Wessex and at York. Chester in 900 may or may not have been an abandonned city of ruins but it was refortified by Æthelflæd. The fact that Chester was still a border location on the fringes of the Irish Sea Region possibly explains the death of Edward the Elder at Farndon and the most likely location of the Battle of Brunanburh, just a little north of Chester.

Unifying England

Brunanburh (937) is often said (especially by the Victorians) to be the battle at which a unified England was created by Æþelstān, but in some ways it resulted in a stalemate, and at best resulted in the nascent "England" surviving rather than being destroyed. After Æþelstān's death, the men of York immediately chose the Viking king of Dublin, Olaf Guthfrithson, as their king, and Anglo-Saxon control of the north, seemingly made safe by the victory of Brunanburh, collapsed. The reigns of Æþelstān's half-brothers Edmund (939–946) and Eadred (946–955) were largely devoted to regaining control. Olaf seized the east midlands, leading to the re-establishment of a frontier at Watling Street. In 941 Olaf died, and Edmund took back control of the east midlands in 942 and York in 944. Following Edmund's death, York again returned to Viking control, and it was only when the Northumbrians finally drove out their Norwegian Viking king, Eric Bloodaxe, in 954 and submitted to Eadred that Anglo-Saxon "control" of the whole of England was finally restored. Upon Eadred's death Eadwig became king but within two years he was forced to share the kingdom with Edgar, who became King of the Mercians, while Eadwig retained Wessex. Eadwig died in 959 after a rule of only four years and England was "reunited" again under Edgar. This is the same Edgar who is famous in Chester for his boat trip on the River Dee and about who suprisingly little else is known. In 962 Edgar granted legal autonomy to the Northern earls of the Danelaw in return for their loyalty; this had limited the powers of the Anglo-Saxon kings who succeeded him north of the Humber. After Edgar's death the throne was disputed between the supporters of his two surviving sons; the elder one, Edward the Martyr, was chosen with the support of Dunstan, the Archbishop of Canterbury. Three years later Edward was murdered (hence his name) and succeeded by his younger half-brother, Æthelred the Unready. Later chroniclers presented Edgar's reign as a golden age when England was free from external attacks and internal disorder, especially compared with Æthelred's disastrous rule.

Back in 628 Penda of Mercia had conquered the small Kingdom of the Hwicca the bounds of this coincided with those of the old Diocese of Worcester, founded in 679–680, the early bishops of which bore the title Episcopus Hwicciorum. The kingdom would therefore have included Worcestershire except the northwestern tip, Gloucestershire except the Forest of Dean, the southwestern half of Warwickshire, the neighbourhood of Bath north of the Avon, part of west Oxfordshire and small parts of Herefordshire, Shropshire, Staffordshire and north-west Wiltshire. This has an agricultural economy then similar in size to that of Essex or Sussex. Leofwine (died in or after 1023) was appointed Ealdorman of the Hwicce by King Æthelred in 994.

England had experienced a period of relative peace in the mid-10th century. However, beginning in 980, when Æthelred could not have been more than 14 years old, small companies of Danish adventurers carried out a series of coastline raids against England. Hampshire, Thanet and Cheshire were attacked in 980, Devon and Cornwall in 981, and Dorset in 982. A period of six years then passed before, in 988, another coastal attack is recorded as having taken place to the south-west. Danish attacks started becoming more serious in the early 990s. Tribute (Danegeld - although not called that at the time) payments by Æthelred did not successfully temper the Danish attacks. Æthelred ordered the massacre of all Danish men in England to take place on 13 November 1002, St Brice's Day. Gunhilde, sister of Sweyn Forkbeard, King of Denmark, was said to have been among the victims. It is likely that a wish to avenge her was a principal motive for Sweyn's invasion of western England the following year. At this stage there are still signs that Mercia had some independent existence: the "C" manuscript of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle has the following entry for the year 1007:

- "In this year also Eadric was appointed ealdorman over all the Mercian kingdom" (geond eall myrcena rice)

By this time the "kingdom" of Mercia is supposed not to have existed as a political entity for around a century at least. Apart from brief reappearance possibly in some form under Æthelflæd and Edgar the Pacific. There are other indications that Mercia was still considered as a political entity. A charter refers to:

- "ealle ða ðegnas ðe þær widan gegæderode wæron ægðer . ge of Westsexan . ge of Myrcean . ge of Denon . ge of Englon" (all the thegns who from far and wide were gathered there, both West Saxon and Mercian, English and Danish)"

Sweyn launched a full-scale invasion of England in 1013 intending to crown himself king. By the end of 1013, English resistance had collapsed and Sweyn had conquered the country, forcing Æthelred into exile in Normandy. But the situation changed suddenly when Sweyn died on 3 February 1014. The crews of the Danish ships in the Trent that had supported Sweyn immediately swore their allegiance to Sweyn's son Cnut the Great. Once Cnut had established himself (see the page on Ælfgar) he divided the country for the purposes of administration:

- "In this year [1017] King Cnut succeeded to all the kingdom of England and divided it into four, Wessex for himself, East Anglia for Thorkel, Mercia for Eadric, and Northumbria for Eric. And in this year Ealdorman Eadric was killed, and Northman, son of Ealdorman Leofwine, and Æthelweard, son of Æthelmær the Stout, and Brihtric, son of Ælfheah of Devonshire. And King Cnut exiled the atheling Eadwig and afterwards had him killed."

The Hwicce area was given to Danes by King Cnut soon after he gained the throne in 1016. However, Leofwine kept his rank and may have been appointed Ealdorman of western Mercia under the authority of Eadric Streona. Leofwine probably did not succeed immediately to the full authority of Ealdorman Ælfhere, for in 1007 he was subordinate to Eadric Streona when the latter was appointed earl of Mercia. He probably remained so under Eadric's successor Eglaf (1017-23). His son was Leofric, who is mentioned in the highly unreliable Chronicle of Croyland as having been a retainer of Eadric.

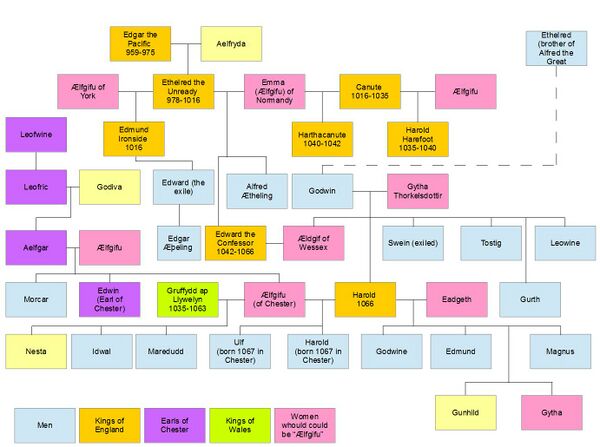

Eventually the earldom of Mercia passed to Leofric (by 1932) and that of Wessex to Godwin. It is sometimes said that the Norman Earls were equivalent to these Anglo-Saxon Earls, but the Norman Earls generally had smaller English regions to govern.

Godwin and Leofric

Becoming Earl of Mercia, made Leofric one of the most powerful men in the land, second only to the ambitious Earl Godwin of Wessex. Godwin was another who had benefited from Cnut, becoming an earl by 1018. Whether there was any family relationship between Leofric and Godwin is difficult to determine although their descendants would have significant interaction.

Godwin was born around 1000 and appears to have been allied with the Danish side, and particularly with Cnut, by an early age. By 1018 he was one of the select few signing Cnut’s Royal Charters. At some point, probably 1022, Godwin accompanied Cnut to Denmark. On his return, Cnut makes him Earl Godwin of Wessex. By 1023 he is appearing on Royal Charters as such. According to some sources Earl Godwin’s position grew after Cnut gave him his sister Estrid in marriage. She herself was a powerful and forceful woman, apparently trading slaves to Denmark, especially young women. However Godwin actually married Gytha Thorkelsdóttir the daughter of Danish chieftain Thorgil Sprakling (also called Thorkel) and the sister of the Danish Earl Ulf Thorgilsson who was married to Estrid Svendsdatter.

Cnut's conquest of England had many advantages for the English. Firstly, the war that had lasted for the entire reign of Æthelred (over 30 years) was now over. As Cnut was engaged in a war of conquest for purely "business" reasons - he wanted to be king - he had no wish to damage his new country. Second, Cnut was one of the most successful and powerful warriors in Europe, as well as still being young - no-one else would be likely to attack the country while he was in charge. Third, he had foreign lands as well, and needed local government to continue while he was abroad, so he put a powerful local leadership in place with delegated authority. This fostered the growth of powerful subjects. As for laws, Cnut took the pragmatic approach to return to the laws of Edgar the Pacific, which effectively allowed the English and the Danes to each live under their own laws. Cnut was generally considered a wise and successful king of a "unified" England although this view may in part be attributable to his good treatment of the Church, keeper of the historic record.

From the above it can be seen that the idea that England was unified and ruled by the English king after the Battle of Brunanburh in 937 is something of a fiction. The remnants of Mercia, Wessex, East Anglia and Northumbria still existed as powerful Earldoms.

Edward the Confessor was the seventh son of Æthelred the Unready and Emma of Normandy. He succeeded Cnut's son – and his own half-brother – Harthacnut. He restored the rule of the House of Wessex after the period of Danish rule since Cnut conquered England in 1016. When Edward died in 1066, he was succeeded by his Edward's wife's brother Harold Godwinson, who was defeated and killed in the same year at the Battle of Hastings by the Normans under William the Conqueror. Edward's young great-nephew Edgar Ætheling of the House of Wessex was proclaimed king after the Battle of Hastings, but was never crowned and was peacefully deposed after about eight weeks. Immediately before the Conquest the Earls in charge were: Harold of the House of Godwin in Wessex, Edwin of the House of Leofric in Mercia and Morcar of the same House in Northumbria. The latter having replaced Tostig Godwinson (Harold's brother) in late 1065.

In summary, the structure of Anglo-Saxon society was fairly flat. The king was the most powerful person in Anglo-Saxon England while Earls/Ealdormen were the most important men after the king. The Old English word ealdorman was applied to high-ranking men in a fairly general sense. It was equated with several Latin titles, including princeps, dux, comes, and praefectus. The title could be applied to kings of weaker territories who had submitted to a greater power. For example, a charter of King Offa of Mercia described Ealdred of Hwicce as "subregulus ... et dux (underking and duke/ealdorman)." Earls collected taxes and got to keep a third of them (the "third penny") with the king getting the rest. Each earldom was divided into shires, with the king's own land overseen, on behalf of the king, by a shire reeve. In Wessex, the king appointed ealdormen to lead individual shires. Under Alfred the Great (r. 871–899), there were nine or ten ealdormen. Starting with Edward the Elder (r. 899–924), it became customary for one ealdorman to administer three or four shires together as an ealdormanry. Each shire was divided into hundreds (equal to 100 hides in some areas). Thegns (“thanes”) were local lords who lived in a manor house and held more than 5 hides of land. A hide can be taken as 120 acres. Thegns had a duty to provide men for the fyrd (army) when needed. Peasants made up most of the population. They worked for their local lord. Ceorls (“curls”) were free to go and work for another lord if they wanted to, although they still had to do some work for their local lord as well. Slaves made up about 10% of the population, and were viewed more as property than people. A peasant could sell themselves into slavery to support their family. Owning slaves was a normal part of life for the Anglo-Saxons, but the Normans thought it was cruel.

The Normans: Formation of the Earldom

Prior to 1066 then, Cheshire was part of Mercia and it's earl was Edwin, the Earl of Mercia. Unlike Northumbria it had little history of being isolated and separately governed so its history is quite distinct from that of the Palatinate of Durham. In terms of economics it was part of the Irish Sea Zone and would have had a mixed population with Saxon, Viking and Welsh roots. Despite what some later writers stated there was no Earl of Chester prior to the Norman Conquest. Comparing a list of Anglo-Saxon Earldoms and one of Norman Earldoms, it is clear that the Norman Earldoms were soon to become far more numerous. The Saxon Earldoms were Northumbria, East Anglia, Wessex and Mercia (all once kingdoms in themselves), with smaller earldoms in Kent and Hereford and briefly Huntingdon and Northampton.

After the Norman Conquest in 1066, the Norman dynasty introduced an adaptation of the French feudal system to the Kingdom of England. Initially, the term "baron" on its own was not a title or rank, but the "barons of the King" were the men of the king. Previously, in the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of England, the king's "companions" held the title of earl and in Scotland, the title of thane.

It is not clear whether William I ever considered Cheshire as anything unique or what his original plans were for "the north". He did eventually make special arrangements for the "Welsh Marches" (a term first used in the Domesday Book of 1086). Here he installed three of his most trusted confidants, Hugh of Avranches, Roger de Montgomerie, and William FitzOsbern, as Earls of Chester, Shrewsbury and Hereford respectively. The March, or Marchia Wallie, was to a greater or lesser extent independent of both the English monarchy and what would become the Principality of Wales or Pura Wallia, which remained based in Gwynedd in the north west of the country. By about AD 1100 the March covered the areas which would later become Monmouthshire and much of Flintshire, Montgomeryshire, Radnorshire, Brecknockshire, Glamorgan, Carmarthenshire and Pembrokeshire. Ultimately, this amounted to about two-thirds of Wales. The Marches would eventually develop the distinctive March law.

After the defeat of the English army and death of Harold Godwinson at the Battle of Hastings, English resistance to the conquest was centred on Edgar Ætheling, the grandson of Edmund Ironside. Ironside was half-brother to Edward the Confessor. It is said that the English conceded defeat, not at Hastings, but at Berkhamsted two months later when Edgar and his supporters submitted to William in December 1066. However, of all the men who submitted to William at Berkhamsted it was only Ealdred, Archbishop of York, who would remain loyal to the Norman king.

Copsi (or Copsig), a supporter of Tostig was a native of Northumbria and his family had a history of being rulers of Bernicia, and at times all of Northumbria. He had been exiled with Tostig in 1965. Copsi had fought in Harald Hardrada's army with Tostig, against Harold Godwinson at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066. He had managed to escape after Harald's defeat. Copsi offered homage to William at Barking in 1067, where William was staying while the Tower of London was being built. William rewarded him by making him earl of Northumbria. After just five weeks as earl, Copsi was murdered by Oswulf, son of Earl Eadulf III of Bernicia. The latter were of the ancient Bernician family which had historically governed the area from Bamburgh. Oswulf appears to have seized control of the earldom of Bamburgh, and was not threatened by any expeditions to remove him. However, in the autumn of 1067, Oswulf, who appears to have been carrying out his duties as earl, intercepted an outlaw and was run through by the man’s spear.

After the "usurping" Oswulf was killed, his cousin, Gospatrick, bought the earldom from William. He was not long in power before he joined Edgar Ætheling, Edwin and Morcar in rebellion against William in 1068. This uprising soon collapsed, and William proceeded to dispossess many of the northern landowners and grant the lands to Norman incomers. King William's authority, apart from minor local troubles such as Hereward the Wake and Eadric the Wild, appeared to extend securely across England.

The next year rebellion broke out again and William had to go north to relieve York. Edgar Ætheling had sought assistance from the king of Denmark, Sweyn II, a nephew of King Canute. Sweyn assembled a fleet of ships under the command of his sons. The fleet sailed up the east coast of England raiding as they went. The Danes with their English allies retook the city of York. Then, in the winter of 1069, William marched his army from Nottingham to York with the intention of engaging the rebel army. However, by the time William's army had reached York, the rebel army had fled, with Edgar returning to Scotland. As they had nowhere suitable on land to stay for the winter, the Danes decided to go back to their ships in the Humber Estuary. After negotiation with William, it was agreed that, if he made payment to them, then they would go home to Denmark without a fight. With the Danes having returned home, William then turned to the rebels. As they were not prepared to meet his army in pitched battle, he employed a strategy that would attack the rebel army's sources of support and their food supply. This was the so-called "Harrying of the North". The land was ravaged on either side of William's route north from the River Aire. His army destroyed crops and settlements and forced rebels into hiding. In the New Year of 1070 he split his army into smaller units and sent them out to burn, loot, and terrify. From the Humber to the Tees, William's men burnt whole villages and slaughtered the inhabitants. Food stores, tools and and livestock were destroyed so that anyone surviving the initial massacre would succumb to starvation over the winter. By the spring of 1070, having secured the submission of Waltheof and Gospatric in Northumbria, and driven Edgar the Outlaw and his remaining supporters back to Scotland, William the Conqueror returned to Mercia, where he based himself at Chester and crushed all remaining resistance in the area. Edwin, Earl of Mercia, would die in 1071. He was apparently making his way to Scotland when he was betrayed to the Normans by his own retinue and killed.

Following this violent consolidation of the Norman Conquest, Chester was held by Gherbod the Fleming, avoué of the Abbey of St Bertin in Flanders. Confusingly, someone named Gherbaud (variously spelt Gherbod or Gerbod) appears in various charters of St Bertin from years 975 until 1096. There appear to have been at least one Gherbod the Monk and at least one Gherbod the advocate. Both Gherbod's family and his eventual fate are a source of considerable confusion and much debate. There is some evidence that Gherbod fought at Hastings in the "Roll of Dives". He was a member of the noble family which owned Oosterzele and Scheldewindeke, south of Ghent and east of the Schelde in the imperial part of the county of Flanders. He held the advocacy of the abbey of Saint-Bertin at Saint-Omer in the western part of the county. Advocates of Saint-Bertin are likely to have been men of substance: it was an important monastery at some considerable distance from Gherbod’s patrimony. The advocacy seems to have passed via Gherbod’s sister Gundrada and her Norman husband William of Warenne to the latter’s sons, who were advocates in the 1090s. Orderic believed that Gherbod held "Cestram et comitatum eius", which might mean the county, or the earldom, or both; the Hyde chronicler saw him as "Comes Cistrensis", which sounds more definite; but both were looking into the early years of the Conquest through a glass which distorted Gerbod’s image into that of a twelfth-century earl. Gherbod is not mentioned anywhere in Domesday, although his brother Frederic is. Frederic supposedly died at the hand of Hereward the Wake, and his lands passed through his sister to William of Warenne.

Hugh of Avranches

Gherbod did not remain in Chester for long. Both Chester Castle and surrounding districts were given (1071) by the king to Hugh of Avranches. A footnote in Gerald of Wales (c1146-1223) tells it thus:

- "The first earl of Chester after the Norman conquest, was Gherbod, a Fleming, who, having obtained leave from king William to go into Flanders for the purpose of arranging some family concerns, was taken and detained a prisoner by his enemies; upon which the conqueror bestowed the earldom of Chester on Hugh de Abrincis or of Avranches, "to hold as freely by the sword, as the king himself did England by the crown."

The footnote seems to have been added in the 1912 text as edited by J. M. Dent and is not based on anything actually found in Gerard's original work, such as a marginal note or a gloss. Many historians have latched onto the last phrase as referring to the creation of a Palatine administration in Cheshire for Hugh of Avranches. The earliest of these, William Camden (1551-1623), wrote:

- By Virtue of this Grant, Cheshire enjoyed all Sovereign Jurisdiction within its own precincts And that in so high a degree that the ancient Earls had Parliaments of their own. Barons and Tenants and were not obliged by the English Acts of Parliament. These high and otherwise unaccountable Jurisdictions were thought necessary upon the Marches and borders of the Kingdom as investing the governors of those provinces with Dictatorial Power and enabling them more effectually to subdue the common enemies of the Nation. And agreeable to these high powers when the style in all legal proceedings of the Courts at Westminster ran "Contra Coronam et Dignitatem Regis", in our County Palatine these pleas were constantly expressed "Contra Dignitatem Gladii Cestris".

Where Camden got this from simply isn't exactly known, although the same phrases occur in a supplication to Henry VI, presented in 1450 (Ormerod, Vol. I, p. 126); Geoffrey Barraclough had little doubt that this supplication constituted the source of Camden's statement. In the supplication Cestrians protest the imposition of taxes by the English Parliament in Cheshire as an infringement of the Palatinate’s rights and privileges:

William Dugdale (12 September 1605 – 10 February 1686) repeats this as quoted in Burke's Peerage of 1831:

- "Which Hugh says Dugdale being a person of great note at that time amongst the Norman nobility and an expert soldier was for that respect chiefly placed so near those unconquered Britains the better to restrain their bold incursions for it was consilio prudentum by the advice of his council that King William thus advanced him to that government his power being also not ordinary having royal jurisdiction within the precincts of his earldom which honor he received to hold as freely by the sword as the King himself held England by the crown."

A further source may be Lucian the Monk his "De laude Cestrie" is preserved in a single late-twelfth-century manuscript (which may be the original and only version). The most likely abbot at the time of Lucians writing was either Geoffry, the seventh Abbot (1194-1208) or less likely Geoffry's successor, Abbot Hugh Grylle (elected 1208, died 1226). The general consensus is that it was written over a number of years and put into its final form around 1195. Lucian describes the county as:

- "enclosed on the other side by the borders of the Forest of Lyme, the province of Chester is, by a certain distinction of privilege, free from all other Englishmen. By the indulgence of kings and the eminence of earls, it gives heed in the assemblies of its provincials more to the sword of its prince than to the crown of the king. Within their jurisdiction, they treat matters of great importance with the utmost freedom"

A marginal note in Lucian's text adds "the earl is obeyed, the king is not feared.". Lucian's text has been described as the earliest extended description of Chester's county palatine status. The book was presented to the Bodleian in 1601, together with eighteen other manuscripts collected by Thomas Allen (1542–1632). Its previous history and how Allen acquired it are unknown, but it is possible that it remained at St Werburgh's until 1539/40, when the library's texts were dispersed on the abbey's dissolution. It does not appear to have been copied and widely read. Indeed, the surviving copy may be the original and unique version of the work.

Henry Bradshaw, who died in 1513 writes of the notions circulating in the early 16th century, and writes of a charter which probably never existed:

- With Wylliam conquerour came to this region

- A noble worthy prince nominate Hug. Lupus,

- […] To whom the kyng gave for his enheritaunce

- The cõunte of Chesshire, with the appurtinaunce,

- By victorie to wynne the forsayd Erldedom,

- Frely to gouerne it as by conquest right;

- Made a sure charter to hym and his succession,

- By the swerde of dignite to hold it with might,

- And to call a parlement to his wyll and syght,

- To order his subiectes after true iustice

- As a prepotent prince and statutes to deuise.

Bradshaw is arguing that Cheshire was independent before the Norman Conquest, but also made independent by the Conquest.

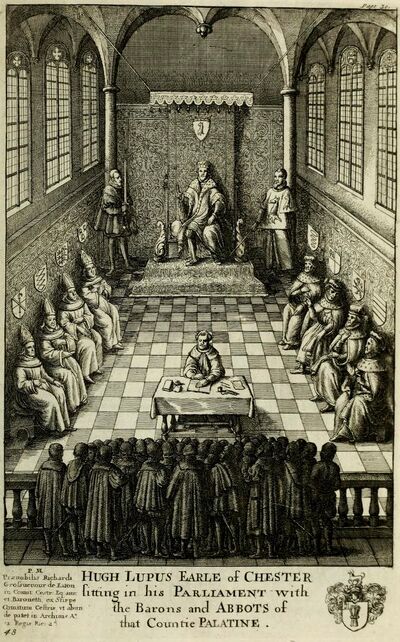

Other post-medieval writers muddied the waters as regards exactly what the status of the Earldom of Chester was. William Smith and William Webb, both native Cestrians, posthumously contributed to Daniel King’s A Vale Royall of England, published in 1656. Smith’s narrative begins with a history of the peculiar privileges of the Palatine of Chester, starting with a description of the “Kings of Mercia” from 585, and detailed reproductions of the Charters granted the county by Henry VI and Elizabeth I which are woven into the chorography of the county, essentially relating the occurrence of one to the other. Smith’s contribution argues the Palatinate’s special status within the realm through its chosen content, and includes a genealogy of the earls of Chester from Leofric to Richard II. Webb describes the “Earls of Chester after the Conquest,” from Hugh of Avranches to Charles I. Significantly, Webb’s account of the earl’s lineage includes a sixteenth-century engraving representing Hugh of Avranches holding Parliament in Chester.

Ormerod and Dugdale were both concerned with family history and genealogy and Camden himself was appointed Clarenceux King of Arms from 1567 to 1623. In 1644 the king appointed Dugdale as Chester Herald of Arms in Ordinary a post he held until 1160.

By Georgian and Victorian times the supposed existence of this early Palatinate juristdiction had become an established "fact". In 1883 William Stubbs (at one time Bishop of Chester) wrote in his "Constitutional History of England":

- The question of the jurisdiction of the earl in his shire is somewhat complicated. In some cases the title was joined to the lordship of all or nearly all the land in the shire in some it conveyed apparently the hereditary sheriffship and in a few cases the regalia or royal rights of jurisdiction. The palatine earldom of Chester is the most important instance of the latter class. The earl as we have seen already was said to hold his earldom as freely by his sword as the king held England by the crown, he was lord of all the land in his shire that was not in the hands of the bishop, he had his court of barons of the palatinate, the writs ran in his name and he was in fact a feudal sovereign in Cheshire as the king was in Normandy.

The term "Earls Palatine" is also found in the work of Henry de Bracton (c.1210 – c.1268) an English cleric and jurist. In discussing the king as the head of the legal system he notes (in the margin):

- "These statements are true unless there be one in the realm who has regalian potestas in all matters, saving lordship to the lord king as prince, as earls palatine..."

He does not mention Chester. The term is found in Matthew Paris in his 13th century description of the marriage of Henry III to Eleanor of Provence in 1236 but it is again unclear to what he refers. Ormerod gives the passage (resonably accurately) as:

- "The earl of Chester then carried the sword of St. Edward, which is called Curtein, before the king, in token that he was an earl palatine, and had power by right to restrain the king if he should do amiss, his constable of Cheshire attending on him, and beating back the people with a rod or staff when they pressed disorderly upon him."

Exactly what Paris means by this is unclear. The sword Curtana however still exists as a 17th century copy. This is a different sword than the supposed sword of Earl Hugh. This sword has generated much confusion among the historians of Chester (see: Arms of Chester). Anthony Tomlin sums it up by pointing out that at various times it was believed to have been:

- Given to the City by Henry VII;

- Offered to James I (who had a morbid fear of blades);

- Removed by Parliament after the Siege of Chester (then returned);

- Seen by Elias Ashmole in the Exchequer of Chester in 1663;

- Sketched again by Daniel Lysons at the British Museum before 1810;

- Viewed in the British Museum by Ormerod in 1819

The lands and possessions of Hugh of Avranches, as recorded fifteen years later in the Domesday inquest, show that he quickly climbed into the first rank in Anglo-Norman society; but there is no evidence to show that his position as earl of Chester was different from, or superior to, that of the great feudal lords in other parts of England. It has also been suggested tha Hugh was a close relative of William I and that Hugh's father was married to a woman from the ducal kindred, and even that he was the Conqueror's nephew. It is difficult to demonstrate any marriage that could have caused this last point to be so.

Despite this, local historians have, from the 17th Century and with few exceptions, been too ready to suppose that the Earl of Chester held from the beginning a unique place among the feudatories of Anglo-Norman England; accepting and repeating the old tradition that William the Conqueror gave Chester to earl Hugh and that the county-palatine, as the deliberate creation of the Conqueror himself, was in existence from 1071. Many add to this that Hugh was William's nephew and some go so far as to make the Grosvenors the descendants of Hugh: both of these appear untrue.

The Normans: changes to the Earldom

Hugh of Chester and Roger of Shrewsbury were the only regional military commanders appointed in Mercia between 1068 and 1070 to be made earls. It is doubtful if the king had a single straight-forward motive. Both men were from important vicecomital families in Normandy. They were appointed at a time when the Anglo-Saxon earldom of Mercia was being broken up, and in fact the Mercian earl’s lands and men throughout Cheshire and Shropshire were placed under their lordship. Both commands were on the Welsh border, where a consolidated fief improved security. In each case the earldom went with a grant of all or virtually all the estates within the county not owned by an English bishop or a foreign monastery. As well as the Earldom of Chester there was the "Honor of Chester" which extended far beyond the borders of the county. The following is a brief sketch of the development of the earldom into the palatinate. Further information on the individual Earls can be found by using the links below the images in the following gallery. The main development during the term of the Norman Earls was not any reduction in the power that the king could exercise, but a growth in the stature and political influence of the Earls and the wealth of their total holdings. The family of Earl Hugh retained their power and their vast estates as the earls of Chester and vicomtes of the Avranchin for generations, while many of the other great magnate families experienced a decline and fall.

Several modern historians have argued that the earls’ exclusive control of Cheshire, apart from the lands of the Church, differentiated Chester from most other earldoms and honors, but was not sufficient in itself to make it a palatine earldom, a status which matured only after the kings of England annexed it in 1241. Geoffrey Barraclough (1951) argued that Earl Hugh had no exceptional powers. Christopher P. Lewis (1991) argues that there is no evidence either way whether Hugh had had exceptional powers beyond those of other Anglo-Norman earls and magnates, but he agrees that it does not seem very likely. More progress can be made with the early history of the honor, though the task is made difficult by the shortage of evidence bearing directly on the formative years of Norman Cheshire. There are only two surviving comital charters before 1086, only five (two of them spurious) before the death of Earl Hugh in 1101, and only nine more before 1129. The absence of charters makes the Domesday evidence vital to understanding how the earls’ lands took shape. Although the honor continued to grow through further royal grants, and to evolve through further subinfeudation, Domesday Book therefore forms the best vantage point for the early history of the honor and the County.

Other modern historians have discussed ways in which the county developed differences and exploited them, particularly in resisting the centralising forces of the Tudor state. Antony Tomlin argues that some of these differences developed at an early date.

Hugh's attempts to conquer territory in North Wales were not a long-term success. This was largely due to a combination of geography and his durable opponent the half-Viking Gruffydd ap Cynan (see: Flintshire), who would leave a largely independent North Wales which would persist through the High Middle Ages, with some ups-and-downs. The success of Hugh, and many of the later earls was in obtaining and retaining land elsewhere. A significant part of this involved chosing which side to back in various conflicts, and generally picking the winning side, whether by luck or judgement. It was probably by this means, rather than any special starting point that by the time of Ranulf de Blondeville the Earldom had become so powerful.

By 1086, the date of Domesday, the honor of Chester extended into no fewer than twenty of the thirty-four English counties, a geographical range rivalled only by the king and his half-brothers Odo of Bayeux and Robert, count of Mortain. Earl Hugh owned manors in six northern counties (Cheshire, Yorkshire, Lincolnshire, Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire, and Leicestershire, also in Rutland) and both East Anglian ones (Norfolk and Suffolk), in six of the seven counties of Wessex (Hampshire, Berkshire, Wiltshire, Dorset, Somerset, and Devon), and in six south Midland counties (Gloucestershire, Oxfordshire, Warwickshire, Northamptonshire, Buckinghamshire, and Huntingdonshire). Cheshire was the most important single county, but alone it accounted for only about a third of the value of Hugh’s lands and there were no contiguous holdings in neighbouring counties. Cheshire was relatively sparsely populated and not particularly productive. Elsewhere the estates granted to Hugh had sometimes dropped in value due to the "Harrying of the North". For example, the estates he was granted in Yorkshire were worth £260 in 1066, but only £10.5 in 1086.

Some writers have argued that the reason why the holdings of Earls were geographically spread out so much, and not in a single geographic block, was to ensure that if they rebelled then they would be unable to defend all of their holdings against the king. Others have argued that the "border" earls needed lands further back from the potential "front line" to provide support and supply. For the wealthier Norman magnates the situation was even more complicated by the fact that they held estates both in England and Normandy.

In 1087, William I died of wounds suffered from a riding accident during a siege of Mantes. On his death-bed he reportedly wanted to disinherit his eldest son but was persuaded to instead divide the Norman dominions between his two eldest sons. To Robert he granted the Duchy of Normandy and to William (II) Rufus he granted the Kingdom of England. The youngest son, Henry, was given money to buy land. Earl Hugh of Chester remained loyal to William Rufus during the rebellion of 1088. Only a few major magnates picked the side of William II, with most taking the side of Robert. The rebels' ranks were made up many of the most powerful barons in England: of the ten largest baronial landholders in the Domesday Book, six were counted amongst the rebels. Hugh had however made the wise choice. William II offered major rewards to his supporters. William won in part because Robert never showed up to support the English rebels. William Rufus added substantial grants to the Earldom of Chester from the royal demesne, amounting to thirty or more manors in Staffordshire, south Derbyshire, south Nottinghamshire, Leicestershire, and Warwickshire. The most notable individual acquisitions were Leek and Coventry, at opposite ends of the area, but most of the rest were clustered in the Trent basin, centring on Repton. Hugh also appeared to side with Wiliam Rufus in 1091 when William and Robert plotted to deprive their younger brother Henry of his lands. Henry had appealed to Hugh for help, but weighing up the relative strengths of the forces involved, publicly sided with Rufus and declared his castles for the king. However Hugh also had some advice for young Henry and suggested that he take up a defensive position at Mont Saint-Michel. Henry was soon besieged on the island fortress and hung-on while his brothers quarrelled. He finally reached a surrender deal which saved his life but drove him into impverished exile. At times during the next years Henry drops out of the records completely although he was probably assisted by Earl Hugh. He resurfaces in Domfront and soon became one of William Rufus' most capable commanders. In 1094 Hugh assisted William in the defence of Normandy against the French king, showing yet another involvement with Henry. As recorded in the AS Chronicle:

- There was the King of France through cunning turned aside; and so afterwards all the army dispersed. In the midst of these things the King William sent after his brother Henry, who was in the castle at Damfront; but because he could not go through Normandy with security, he sent ships after him, and Hugh, Earl of Chester.

The circumstances of the death of William Rufus are suspicious, especially given the death of Robert's son Richard in similar circumstances just a few months before. Historians are still somewhat divided on whether "hunting accidents" are the expected results of a dangerous sport (and probably alcohol) or a convenient way of disposing of someone. Henry I became king and once again the Earl of Chester was on very good terms with the monarch.

Asyla

Hugh also created three asyla for those seeking "refuge" in Cheshire. These were at Hoole Heath near Chester, Overmarsh near Farndon and Rud Heath near Middlewich. These were places to which a felon from any place in England (or Wales) could flee and seek the protection of the Earl. The sanctuary at Hoole Heath may well be the reason for the bad reputation of Newton Hollows attributed to Lucian the Monk. Hemingway describes them as follows:

- These sanctuaries were the source of much emolument to the earls, who received fines from all such persons when they came to reside under their protection a heriot at their death and in case of their dying without issue claimed their goods and chattels.

Thus we see that the tale of criminals being free if they escaped the "hue and cry" and reached Chester is only partly true. Much later, in the times of Edward II, they were described as follows:

- By an inquisition taken before Hugh de Audelith Justice of Chester on Sunday after the feast of St Peter ad Vincula it was found That a certain large piece of Waste called Overmarsh was in ancient times ordained for strangers of what country soever and assigned to such as came to the peace of the Earl of Chester or to his aid resorting there to form dwellings but without building any fixed houses by the means of nails or pins save only booths and tents to live in.

In in the reign of Edward III:

- The jury declare upon their oaths that the Moor which is called Rudheath was formerly a waste place very anciently assigned and set apart by some of the old Earls of Chester for the reception not of their own subjects but of all fugitive strangers coming to the aid of the Earl's peace either from England or from any other countries And there is an inquisition of the same tenor relative to the other of Hoole Heath.

The practice of "Avowry" in Cheshire required any new-comer who required the protection of the lord, for whatever reason, to seek “to place himself in the avowry” of the lord within three days of his arrival. If he remained longer than three days without doing so, his goods and assets would be seized and forfeit to the lord. If, however, he negotiated an avowry-rent with the keeper of the avowries, usually for a small yearly payment of between 1d and 4d plus other obligations to the upkeep of the lord and his system, the new-comer received the protection of lord from prosecution for previous offences or debts. After an untroubled residence of a year and a day in the County Palatinate, newly avowed received the Earl’s permanent protection for life. The avowry was inheritable, and as such passed the protection of the earl, for the same annual payment, to the heirs of the avowed upon death. As Lucian the monk noted, Cestrians are "by a certaine licentious liberty, bold in borrowing many times others men goods (sic)." It seems from Lucian’s description, avowries may also have provided a way for Cheshire men to leave the county to raid other’s goods, and return to the safety of the Palatinate and protection from prosecution for their crimes. Once the avowed had completed the necessary residency period without incident, if they subsequently committed a crime outside the county and were pursued at home, the earl’s representative would stand in defense of the accused.

Richard of Avranches

When Earl Hugh died in 1101 he was succeeded by his son Richard of Avranches who had been born in 1094 and hence was still a youth of seven years and thus a minor. The earldom prior to its royal "take-over" would pass to a minor again with Hugh de Kevelioc and for a final time with Ranulf de Blondeville. Other earldoms were not so fortunate to have a minor son available and in some case became dispersed among the husbands of female co-heirs.

The first part of King Henry's reign is occupied by his efforts to defend his newly acquired kingdom of England from his brother, Robert Curthose. For this imminent purpose he had to secure the support of the powerful magnates. Henry's relationship with the family of the earls of Chester, may be taken as an interesting example in this respect.

The new king Henry I (who ruled from 1100) all but adopted the child and sent him off to Normandy to be educated with his own children, conveniently obtaining a more-or-less free hand with the young Earl's lands during his minority. The young Richard's presence at the royal court can also be interpreted in some respects as his being held "hostage" under comfortable circumstances and educated to be loyal to Henry. Indeed, even after he came of age Earl Richard appears to have prefferred to remain in Normandy and enjoy society leaving the supposed Palatinate to become what was effectively a royal-fief. The very fact that Crown appointees managed his estates rather than some form of "regency" illustrates that the Palatinate was not the quasi-independent state that some have claimed it to be.

Earl Richard's marriage to the king's niece Matilda, c 1115, also shows King Henry's serious concern to advance the young earl as well as building a strong network of supporters both for himself and his own son, who he expected to be the future king. Unfortunately, the line of the d'Avranches as Earls of Chester failed when Hugh's son Richard, with his illegitimate half-brother Ottuel, joined the young prince William Adelin (heir to Henry I) aboard the doomed White Ship on 25th November 1120. The ship foundered, drowning all but one, and Richard died aged 26, leaving no issue.

Ranulf de Meschines

The next earl was Ranulf de Meschines and only became earl at the rather advanced age of 51. A good part of his career involved Cumberland which William Rufus had captured in 1092, building Carlise Castle. Between 1098 and 1101, probably in 1098, Ranulf I became a major English landowner in his own right when he became the third husband of Lucy of Bolingbroke, heiress of the honour of Bolingbroke in Lincolnshire. This marriage brought him the lordship of Appleby in Cumberland, previously held by Lucy's second husband (Roger fitzGerold, de Roumare). He promptly constructed Appleby Castle. By 1101 William the Conqueor's sons, Robert Curthose and Henry I were still fighting, and Robert led an invasion to oust his brother Henry.

Ranulph threw in his lot with Henry and was entrusted with collecting oaths of support. Robert landed at Portsmouth with his army, but the lack of popular support among the English (Anselm, the archbishop of Canterbury, was decidedly against him and the Charter of Liberties issued at Henry's coronation was well liked - if largely ignored by monarchs) as well as Robert's own mishandling of the invasion tactics enabled Henry to resist the invasion. Ranulf was one of the magnates who accompanied King Henry on his invasion of Duke Robert's Norman territory in 1106. Ranulf served under Henry as an officer of the royal household when the latter was on campaign; Ranulf was in fact one of his three commanders at the Battle of Tinchebrai (1106). The first line of Henry's force was led by Ranulf. It is not clear whether Ranulf's authority in Cumberland came about before his service at the Battle of Tinchebrai or was a reward for it, but it is possibly notable that both of his wife's first two husbands had connections with the region.

Henry faced a particularly dangerous situation in 1118 having been defeated by Fulk V and the Angevin army, supporters of Louis VI of France. Forced to retreat, Henry's position deteriorated alarmingly, as his resources became overstretched and more barons abandoned his cause. Orderic Vitalis makes it clear that Richard of Avranches and Ranulf were among a very small number who remained loyal to Henry in 1119.

When Richard of Avranches was drowned, the Welsh at once revolted, and King Henry needed to replace him quickly. Ranulf had recognised military ability and social strength, he was loyal and he was the closest male relation to Earl Richard. But there was a counter-side: Ranulf ceded Appleby to the crown when he became earl of Chester as well as losing much of his wife's lands in Lincolnshire. Some historians believe that this was just part of an exchange, others that Henry feared that Ranulf would otherwise become too powerful and one proposed that Ranulf had to actually purchase the County of Chester and raise the money to do this by selling other land. Some writers have suggested that this was a payment of "Feudal relief", which again weakens the argument that the "palatinate" as a special type of entity was already in existence.

Between 1120 and 1123, Earl Ranulf made several edicts that converted the Wirral into a hunting forest. This made the area subject to Forest Law which made the hunting of game, such as deer and boar, by unauthorised persons subject to harsh penalties. To enforce the forest laws was a chief forester who was appointed with a ceremonial horn, and the position soon became a hereditary responsibility of the Stanley family. However, after complaints from minor Wirral landowners about the wildness of the area and oppression by the Stanleys, Edward the Black Prince as Earl of Chester agreed to a charter confirming the disafforestation of the Wirral, shortly before his death from amoebic dysentery. The proclamation was issued by his father Edward III on 20 July 1376.

Ranulph De Gernon

Ranulph De Gernon became earl in 1128. In late January 1136, during the first months of the reign of Stephen of England, his northern neighbour David I of Scotland crossed the border into England. Northern England was a disputed territory at this time, with the Scottish kings laying a traditional claim to Cumberland, and David also claiming Northumbria by virtue of his marriage to the daughter of Waltheof, Earl of Northumbria. David took Carlisle, Wark, Alnwick, Norham and Newcastle upon Tyne and struck towards Durham. On 5 February 1136, Stephen reached Durham with a large force of mercenaries from Flanders and forced David to negotiate a treaty by which the Scots were granted the towns of Carlisle and Doncaster, for the return of Wark, Alnwick, Norham and Newcastle. Lost from England to Scotland along with Carlisle was much of Cumberland and the honour of Lancaster, lands that belonged to Earl Ranulf's father and had been surrendered by agreement to Henry I of England in return for the Earldom of Chester. In the second Treaty of Durham (1139), Stephen was even more generous to David, granting the Earldom of Northumbria (Carlisle, Cumberland, Westmorland and Lancashire north of the Ribble) to his son, Prince Henry. Ranulf was prepared to revolt in order to win back his lordship of the north. He changed sides to Matilda, but this was to be only the first time that he switched his loyalty between Stephen and Matilda.

By this time Matilda, named as the future Queen by her father Henry I, had gathered enough strength to contest Stephen's usurpation, supported by her husband Geoffrey of Anjou and her half-brother Robert of Gloucester. Ranulph's first plan was to capture Prince Henry, but this failed. Ranulf then used subterfuge to seize Lincoln Castle. Stephen eventually made a pact with Ranulf and his half-brother and left Lincolnshire, returning to London before Christmas 1140, after making William de Roumare Earl of Lincoln and awarding Ranulf with administrative and military powers over Lincolnshire and the town and castle of Derby.

The citizens of Lincoln soon sent Stephen a message complaining about the treatment they were receiving from Ranulf and asking the King to capture the brothers. The King immediately marched on Lincoln. One of his key pretexts was that according to the settlement, Lincoln Castle was to revert to royal ownership and that the half-brothers had reneged on this. He arrived on 6 January 1141 and found the place scantily garrisoned: the citizens of Lincoln admitted him into the city and he immediately laid siege to the castle, captured seventeen knights and began to batter down the garrison with his siege engines. Ranulf managed to escape to his earldom, collect his Cheshire and Welsh retainers and appeal to his father-in-law Robert of Gloucester, whose daughter Maud was still besieged in Lincoln, possibly as a deliberate ploy to encourage her father's assistance. In return for Robert's aid, Ranulf agreed to promise fidelity to the Empress Matilda.

To Robert and the other supporters of the Empress, this was good news, as Ranulf was a major magnate. Robert swiftly raised an army and set out for Lincoln, joining forces with Ranulf on the way. Stephen held a council of war at which his advisors counselled that he leave a force and depart to safety, but Stephen disregarded the odds. He decided to fight, but was obliged to surrender to Robert. Ranulf took advantage of disarray amongst the king's followers and in the weeks after the fighting managed to take the Earl of Richmond's northern castles and capture him when he tried to ambush Ranulf. Richmond was put in chains and tortured until he submitted to Ranulf and did him homage. Stephen had been effectively deposed and Matilda ruled in his place.

In September 1141, Robert of Gloucester and Matilda besieged Winchester. The queen responded quickly and rushed to Winchester with her own army, commanded by the professional soldier William of Ypres. The queen's forces surrounded the army of the empress, commanded by Robert, who was captured as a result of deciding to fight his way out of the situation. The magnates following the empress were forced to flee or be taken captive. Earl Ranulf managed to escape and fled back to Chester. Later that year Robert was exchanged for Stephen, who resumed the throne. In 1144 Stephen attacked Ranulf again by laying siege to Lincoln Castle. He made preparations for a long siege but abandoned the attempt when eighty of his men were killed whilst working on a siege tower that fell and knocked them into a trench, suffocating them all.

In 1145 (or early 1146) Ranulf switched allegiance from the Empress Matilda to Stephen. Since 1141 King David had been allied to Matilda, so Ranulf could now take up his quarrel with David of Scotland regarding his northern lands. It is probable that Ranulf's brother-in-law Phillip, (the son of Earl Robert), acted as an intermediary as Phillip had defected to the king. Ranulf came to Stephen at Stamford, repented his previous crimes and was restored to favour. He was allowed to retain Lincoln Castle until he could recover his Norman lands. Ranulf's opponents counselled the king that the earl might be planning treachery since he had offered no hostages or security, resulting in Ranulf's arrest. It was eventually agreed that the earl should be released, provided he surrendered all the royal lands and castles he had seized (Lincoln included), gave hostages and took a solemn oath not to resist the king in future. Ranulf revolted as soon as he regained his liberty.

In May 1149 the young Henry FitzEmpress met the king of Scotland and Ranulf at Carlisle, where Ranulf resolved his territorial disputes with Scotland and an agreement was reached to attack York. Stephen hurried north with a large force and his opponents dispersed before they could reach the city. The southern portion of the honour of Lancaster (the land between the Ribble and the Mersey) was conceded to Ranulf, who in return resigned his claim on Carlisle. Henry, whilst trying to escape south after the aborted attack on York, was forced to avoid the ambushes of Eustace, King Stephen's son. Ranulf assisted Henry, creating a diversion by attacking Lincoln, thus drawing Stephen to Lincoln and allowing Henry to escape.

In 1153 Henry, by then Stephen's accepted heir, granted Staffordshire to Ranulf. That year, whilst Ranulf was a guest at the house of William Peverel the Younger, his host attempted to kill him with poisoned wine. Three of his men who had drunk the wine died, while Ranulf suffered agonizing pain. A few months later Henry became king and exiled Peverel from England as punishment. Ranulf succumbed to the poison on 16 December 1153: his son Hugh inherited his lands as held in 1135 (when Stephen took the throne), while other honours bestowed upon Ranulf were revoked. Some historians like David Crouch suggest that by 1150 the earldom of Chester was already a quasi-principality. Others such as James Alexander argued that there is no evidence for the palatinate status of Chester or any other such lordship until much later in the thirteenth century.

There is a further slight peculiarity from Ranulf's time as Earl. This relates to his charter to Alan Silvester, the master-forester of Wirral. Curiously, such a charter would normally be addressed to various high officials including the Justice or Justicar, but no such person is mentioned. The justice is mentioned frequently in charters dating fron the 13th century, but in the time of Ranulf II there is a rare attestation by "Adam justicia Comitis" in a private charter to Chester Abbey, dated 1130-50 and Ranulf II mentions "justicia mea Cestrie" in a charter of 1141-53. R Stuart-Brown, in 1935, questioned whether this could shed light on when the "independent" legal system of the palatinate came into existence.

Hugh de Kevelioc

Hugh de Kevelioc born in 1147 became Earl as a minor in 1153 and Chester was once again in royal hands, under Henry II, for a while, until 1162, when Hugh was quick to become involved in political matters:

- "He quickly took his place among King Henry II's magnates, being present at Dover in 1163 for the renewal of the Anglo-Flemish alliance and in 1164 at the Council of Clarendon." (Oxford Dictionary of National Biography)

At around this time Henry II was having problems with the Welsh. Owain Gwynedd, had used England’s civil war to expand his territories and establish dominance in northern Wales. In 1150 Owain secured Tegeingl in the north-east, posing a threat to Chester. In early 1165 Owain Gwynedd's son Dafydd ravaged and plundered the cantref of Tegeingl, threatening the Norman castles at Rhuddlan, Basingwerk and Prestatyn. Later in 1165 Henry II led a large-scale but ill-fated campaign into Wales by way of Shrewsbury, only to be harried by Welsh archers, possibly at the Battle of Crogen and bogged down by torrential rains on the Berwyn mountains. This was not Henry's first attempt on Wales, in 1157, Henry had been involved in a skirmish near Basingwerk in which he was nearly killed. Henry II seems to have abandoned hope of achieving direct dominion over Wales after these disasters. Henry's retreat in 1165 brought him through Chester where he apparently mutilated Welsh hostages. It is not known to what extent Hugh de Kevelioc was involved in the campaign. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography states of him:

- "On his father's death in 1153, he became heir to extensive estates. In France, these included the hereditary viscountcies of Avranches, Bessin, and Val de Vire, as well as the honours of St Sever and Briquessart. In England and Wales, there was the earldom of Chester with its associated honours. Together, they made him one of the most important Anglo-Norman landholders when he was declared of age in 1162 and took possession"

In 1173, (aged 26) Hugh joined the baronial Revolt of 1173-1174 against Henry II. A leading figure in this revolt was Henry II's heir "Henry the Young King". Henry fell out with his father in 1173. Contemporary chroniclers allege that it was due to the young man's frustration that his father had given him no realm to rule, and that he felt starved of funds. The rebellion seems however to have drawn strength from much deeper discontent with his father's rule, and a formidable party of English and Norman magnates joined him. William of Newburgh wrote:

- "Then many powerful and noble persons, as well in England as in foreign parts, either impelled by mere hatred, which until then they had dissembled, or solicited by promises of the vainest kind, began by degrees to desert the father for the son, and to make every preparation for the commencement of war. The earl of Leicester, for instance, the earl of Chester, Hugh Bigot, Ralph de Fougeres, and many others, formidable from the amount of their wealth and the strength of their fortresses."

The civil war (1173–74) came close to toppling the king, and he was narrowly saved by the loyalty of a party of English court aristocracy and the defeat and capture of the king of Scotland. Hugh had chosen the losing side and lost Chester Castle and the rest of his lands when captured at Dol (not at Coventry Castle as sometimes stated) and imprisoned. While shuttled about somewhat he was finally placed in confinement at Caen. Curiously, Barraclough notes that some contempories called the civil-war Hugh de Kevelioc's war, but he does not elaborate or give sources.

At the Council of Northampton in January 1177 his lands were restored, but not his castles, and in March he was a witness to Henry's arbitration between the kings of Castile and Navarre. Then in May, at the Council of Windsor, Henry restored his castles and ordered him to Ireland. Hugh then supposedly went to Ireland with William Fitzaldhelm to prepare for the arrival of the king's son John. There is no record of him gaining any military successes or grants of land there and it has even been suggested he never actually went.

One mystery is why Hugh II got his lands and castles back in 1177. The revolt lasted eighteen months, played out across a large area from southern Scotland to Brittany. At least twenty castles in England were recorded as demolished on the orders of the king, many towns were destroyed (including Nottingham and Norwich) and many people were killed. William of Newburgh provides no explanation other than the clemency of Henry II.

Ranulf de Blondeville

Ranulf de Blondeville was another minor when he became earl in 1181 at age 9. Ranulf would become a central figure of the Angevin court during the reigns of Henry II, Richard I, John, and Henry II.

Ranulf would spend his minority at Henry II's court at Domfront in Normandy. He was not quite a prisoner. His early companions would have included Constance of Brittany, whom he was later to marry, and possibly also Otto of Brunswick (born 1175). During his minority Ranulf's inheritance was administered first by Gilbert Pipard and later by Bertram de Verdon. Gilbert Pipard served as sheriff of Gloucester and Hereford and guardian of Chester before travelling to Ireland with John, son of Henry II, in 1185 and receiving grants of Ardee in Louth and most of Monaghan. He went on crusade with Richard I and died at Brindisi in 1191. Bertram de Verdon (III) was sheriff of Leicestershire until 1183 and a deeply religious man accompanying Henry II on his pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostella in North of Spain. After Prince John's first expedition to Ireland, Bertram held the town of Dundalk and several castles in Louth. Following Henry II’s death Bertram III remained an influential figure with Richard I and became his castellan, went on the Third Crusade with Richard, was governor of Saint-John of Acre and died at Jaffa in 1191. Both Pipard and de Verdon were probably instrumental in instilling in the young Ranulf the loyalty to the crown and strong sense of honour which was a characteristic of his long tenure as Earl.

Ranulf was styled as Duc de Bretagne between 1189 and 1199 and as Earl of Richmond between 1189 and 1199. He was a commander of the forces of King Richard I in 1194. He lost the viscounty of Avranches in 1204 with the Capetian conquest of Normandy but he still held substantial estates; at the end of the 12th century he was supposed to be able to muster 80 knights from his Cheshire lands and his English lands were supposed to be able to muster 118 knights which would have meant Ranulf could have mustered 198 knights, in theory. He fought in the Wars with the Welsh between 1209 and 1214. He held the office of Governor of Newcastle-under-Lyme in 1215, and also of Governor of the Peak Castle and Forest.

By this time distinctive institutions had begun to emerge which set the county of Chester apart from other English shires. There seems to have been an embryonic Chancery and Exchequer, a Justice who was the equivalent of the king's Justiciar and a chief clerk corresponding to the king's Chancellor. The name of the Justice from c.1202 is recorded as Philip Orreby and he may have been the first to hold the office formally. A list of Justices is given by Peter Leycester but this disagrees with lists given elsewhere.