John Canmore

John the Scot (First Earl, Third Creation) Last Anglo-Norman Earl

(Kings: Henry III)

Summary

Another indirect claim and another possible poisoning.

- Parents: David of Scotland, Earl of Huntingdon by his wife Maud of Chester (1171-1233), daughter of Hugh de Kevelioc (Earl of Chester).

- Spouse: Elen ferch Llywelyn, daughter of Llywelyn the Great

- Brothers and sisters: Henry of Huntingdon, Robert of Huntingdon, Margaret of Huntingdon, Isobel of Huntingdon, Ada of Huntingdon, Matilda of Huntingdon

- Children: none

A well-connected Earl

John of Scotland or John de Scotia (c. 1207 – 6 June 1237), sometimes known as "the Scot", was an Anglo-Scottish magnate, the son of David of Scotland, Earl of Huntingdon by his wife Maud of Chester (1171-1233), herself the daughter of Hugh de Kevelioc (Earl of Chester). David of Scotland (c. 1144 – 17 June 1219) was the youngest surviving son of Henry of Scotland, so his paternal grandfather was David I of Scotland.

John married Elen ferch Llywelyn, daughter of Llywelyn the Great, in about 1222. The records of Llywelyn's family are confusing, and it is not certain which of his children were illegitimate, but Elen appears to have been his legitimate daughter by Joan, Lady of Wales, herself illegitimate daughter of King John of England.

John became Earl of Huntingdon in 1219 on the death of his father, and was a minor at the time. During his minority the custody of the honour was given to the king of Scotland (Alexander II of Scotland), who granted it to Ranulf de Blondeville, Earl of Chester and John's uncle when Ranulf returned from Crusade in 1220. John probably came of age in 1227, when he did homage for Huntingdon.

John became Earl of Chester in 1232 on the basis of his connection to the previous earl, Ranulf de Blondeville, who was his mother's brother. On her brother Ranulf's death in October 1232 Matilda inherited a share in his estates with her other 3 sisters, and his Earldom of Chester suo jure (in her own right). Less than a month later with the consent of the King, Matilda gave an inter vivos (while still alive) gift of the Earldom to her son John the Scot who became Earl of Chester by right of his mother. He was formally invested by King Henry III as Earl of Chester on 21 November 1232. He became Earl of Chester in his own right on the death of his mother six weeks later.

The granting of the earldom of Chester to one of earl David Ceann mhor's sons was probably an attempt to reduce conflict on the Northern Marches of England. There was some conflict over the succession to the Earldom but this was in the courts rather than on the battlefield. In proceedings headed, "Placita coram Domini Rege apud Westm: a die Paschæ in XV. dies." [22nd April, 1235.] it is recorded that:

- John, Earl of Chester and Huntingdon, was summoned to answer the complaint of Hugh de Albini, William, Earl of Ferrars, and Agnes his wife, and Hawise de Quency, Countess of Lincoln, that he had deforced them of their reasonable share of the inheritance of Ralph, formerly Earl of Chester, and of which Ralph had died seised in the county of Chester, taking into account the shares they as well as John had received in other parts of the same inheritance; and they say that the said Earl holds the capital messuage in Chester, and Hugh de Albini has Coventry, with other lands; William de Ferrars and Agnes his wife have Certeslegh (Chartley), with other lands; and Hawise de Quency has Bullingbrock, with other lands. And the Earl of Chester appeared by his attorney, and pleaded he ought not to answer to this plaint and summons, which referred to lands in Cheshire, because the King's writ did not run in Cheshire; and he asked that the King should maintain his liberties such as he and his ancestors had held, and that the said complainants should appear in the county of Chester, where he would do them full justice. The Earl of Ferrars and the other plaintiffs who are heirs and coparceners of the said inheritance pray the judgment of the King. The suit is respited to the morrow of St. John the Baptist, to be heard before the King.

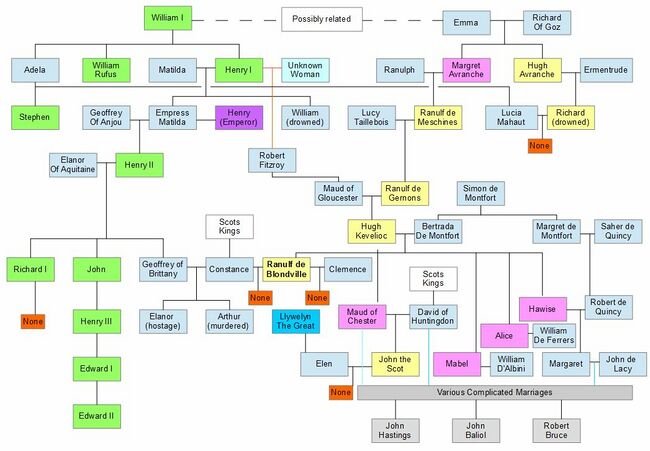

To explain all this it is useful to refer to the family tree chart below. Since Ranulf had died without issue the earldom might have been deemed to return to the Crown. Why it did not do so is complex:

- There was a precident. When Richard of Avranches died in 1120, the succession went back up to his aunt and then down to her son Ranulf de Meschines.

- Ranulf de Blondeville had left a detailed will upon his death in 1232 - discussed below.

- Relations with neighbouring states (Wales and Scotland) were complex.

- Justicar Hubert de Burgh was about to fall and the revolt of Richard Marshal would soon break out.

Henry III's accession had been far from smooth. When his father John has sought to renege on the Magna Carta in late 2015 a number of English barons had called upon French Prince Louis to claim the English throne. Those who remained loyal to the Crown included Ranulf de Blondeville and William Marshall. Prelates who remained loyal included Stephen Langton (died 1228) and Peter des Roches. As part of the process of putting the young king in a secure position the Magna Carta was re-issued. This was an attempt to prevent any return to the tyranny of his father John. The rivalry between Peter des Roches and Hubert de Burgh would be an important issue in events as they unfolded.

Scotland and England

The relationship of Scotland with Henry II and his sons is complicated. David I of Scotland had married Matilda of Huntingdon, daughter and heiress of Waltheof, Earl of Northumberland. The marriage brought with it the "Honour of Huntingdon", a lordship scattered through the shires of Northampton, Huntingdon, and Bedford. Within a few years, Matilda bore a son, whom David named Henry after his patron. The new territories which David controlled were a valuable supplement to his income and manpower, increasing his status as one of the most powerful magnates in the Kingdom of the English. Northumberland was now a defunct lordship which had covered the far north of England and included Cumberland and Westmorland, Northumberland-proper, as well as overlordship of the bishopric of Durham. After King Henry's death, David revived the claim to this earldom for his son, also named Henry. The treaties between David and Stephen led to the Scottish territory extending south to the rivers Ribble and Tyne. For more on the effect of the Earls of Chester see Ranulf de Meschines and Ranulph De Gernon. David's plans took a blow in 1152 when his son Henry died: and his grandson Malcolm (aged 11) was made heir apparent. Malcolm IV became king in 1153 and granted Northumbria to his brother William, keeping Cumbria for himself. Cumbria was, like the earldoms of Northumbria and Huntingdon, and later Chester, a fief of the English crown. While Malcolm delayed doing homage to Henry II of England for his possessions in Henry's kingdom, he did so in 1157 at Peveril Castle in Derbyshire and later at Chester. Malcolm died in 1165 and the Crown of Scotland passed to William. In the Revolt of 1173-74 (see: Hugh de Kevelioc) William took the side of Henry the Young King, who may have promised him land in the North of England. In 1174, at the Battle of Alnwick, during a raid in support of the revolt, William recklessly charged the English troops and was captured. The price of his freedom was the Treaty of Falaise in which William accepted England's dominion over Scotland. The treaty was annulled in 1189 when King Richard I, Henry's successor, was distracted by his interest in joining the Third Crusade, and William's offer of 10,000 silver marks. When William ascended to the Scottish throne the Earldom of Huntingdon went to his younger brother David. It was David who was married to Matilda of Chester (Ranulf de Blondville's sister) and was the father of John the Scot.

Sir Walter Scott's 1825 novel The Talisman features Earl David in his capacity as a prince of Scotland as a crusader on the Third Crusade. For the majority of the novel, Earl David operates under an alias: Sir Kenneth of the Couchant Leopard. Earl David's adventures are highly fictionalized for this novel. He was heir to the Scottish throne until 1198 and the birth of Alexander II of Scotland.

In the later litigation for succession to the crown of Scotland in 1290–1292, the great-great-grandson Floris V, Count of Holland of David's sister, Ada, claimed that David had renounced his hereditary rights to the throne of Scotland. He therefore declared that his claim to the throne had priority over David's descendants. However, no explanation or firm evidence for the supposed renunciation could be provided.

Ranulf de Blondeville had arranged for his will to name four co-heirs after his death in 1232 all of whom were his sisters or their heirs. There was a temporary settlement shortly after Ranulf's death with a specificic manor allotted to each as a chief seat, the idea being that they could come to some arrangement if they were not satisfied:

- Matilda of Chester: John's mother. With her share went the Earldom of Chester and both Chester Castle and Beeston Castle.

- Mabel: who married Wlliam D'Albini 3rd Earl of Arundel. William was a favourite of King John. He witnessed King John's concession of the kingdom to the Pope on 15 May 1213. On 14 June 1216 he joined Prince Louis (later Louis VIII of France) after King John abandoned Winchester. He returned to the allegiance of the King Henry III after the Royalist victory at Lincoln. He joined in the Fifth Crusade (1217–1221), in 1218. He died on his journey home, in Caneill, Italy, near Rome, on 1 February 1221. News of his death reached England on 30 March 1221. His title was inherited by his son William, the fourth Earl. The fourth earl died childless and in 1224 the title passed to his brother, Hugh, who was alive at the time that Ranulf died but a minor.

- Alice (or agnes): who married William de Ferrers. On Richard's return from the Third Crusade, in the company of David Ceannmhor and Ranulf he played a leading role in besieging Nottingham Castle. He also took part, with Ranulf in the Battle of Lincoln. As the Earl advanced in years he became a martyr to severe attacks of the gout, a disease which terminated his life in the year 1247. He was succeeded by his elder son, also William, the Fifth Earl of Derby, who would die in 1254. To these went Chartley Castle as their chief seat together with West Derby in Lancashire, all the land between the Ribble and the Mersey: which included Liverpool, Salford and Leyland, as well as land in Northhamptonshire and Lincolnshire.

- Hawise: who married Robert de Quincy. She would pass on the Earldom of Lincoln to her daughter Margaret de Quincy who then became 2nd Countess of Lincoln suo jure and her son-in-law John de Lacy, Baron of Pontefract who then became the 2nd Earl of Lincoln by right of his wife. De Lacy is the same hereditary Constable of Chester, who was the son of Roger de Lacy (1170–1211) who served Ranulf for many years. Bolingbroke Castle was the chief seat of this share.

Life

John leaves little mark on history, althought one source put him on the side of the Barons led by Richard Marshal in revolt (1233) against Henry III:

- Henry III soon after the suppression of an insurrection headed by John Earl of Chester and Richard Earl of Pembroke principal Lords Marchers resolved upon the conquest of Wales with his own proper forces The Earl of Chester dying soon after without male issue the King resumed by composition made with the Earl's four sisters and heirs the county palatine of Chester granted by the Norman Conqueror to the first Earl his kinsman and with it the greater part of the county of Flint which the Earls of Chester as Lords Marchers had won from the Welsh - "The History & Antiquities of the Town of Ludlow, and Its Ancient Castle; With Lives of the Presidents, and Descriptive and Historical Accounts of Gentlemen's Seats, Villages, &c" By Thomas Wright.

There is a possible reference to how this insurrection was settled in the patent rolls - see Feb 3rd entry. This entry refers both to the Earl of Chester and to Gilbert Marshal who was the brother of Richard Marshal. In 1233 Richard Marshal had made an alliance with the Welsh Llywelyn the Great (John's father-in-law). Richard Marshal crossed from Wales to Ireland, where Peter des Roches (Bishop of Winchester) had instigated his enemies to attack him, and in April 1234 he was overpowered and wounded, and died a prisoner.

There also appears to be more intrigue here as Matthew Paris states that the Constable of Chester (John de Lacy) was also influenced by the same Bishop:

- "was brought over to the king's party, with John le Scot, Earl of Chester, by Peter de Rupibus, Bishop of Winchester, for a bribe of 1,000 marks".

By 1236 John was well in with the king, he carried the broken sword "Curtana" at the coronation of Eleanor, the twelve-year old wife of Henry III.

John appears to have made a vow to go on crusade, but died before he could. He would have joined the Barons' Crusade (1239–1241).

Death

The shadow of yet more treachery is suggested in Glover's "history and gazetteer of the county of Derby":

- In eight years after the death of earl Ranulph, expired his nephew, John the Scot, the last earl of Chester, without issue, poisoned by Helena his wife, the daughter of Llewellyn, prince of Wales. These unhappy espousals had been brought about by the policy of earl Ranulph, who by means of them secured certain present privileges, and expected that the regalities ofthat old British principality would one day be enjoyed by his sister's descendants. On the demise of earl John the Scot, the prerogatives of the palatinate were assumed by the crown, on the plea " tie tarn prteclara dotninatio inter colot Jiceminarum dividí contingeret." — " Lest it should happen that so illustrious a dominion should fall under the divided sway of the distaffs of women."

One curious fact about John's death is found in the "calender of patent rolls". While John is generally accepted to have died on June 6th/7th 1237 (dates vary), the patent rolls record that Henry III was sending his condolences on June 6th 1237. The poison story turns up again in the "Notitia cestriensis: or Historical notices of the diocese of Chester" which contains the footnote:

- John Scot (so called because a Scot by birth) was the last Earl of Chester and Huntingdon, and died June 7th, 1237, without issue male, having married Helen, daughter of Lewellin, Prince of Wales, by whom he was poisoned, according to the testimony of several ancient chroniclers.

And poison can be found again, perhaps here it originated, in Matthew Paris (who is not always to be believed):

- About this time, too, John Scott, earl of Chester, closed his life about Whitsuntide, having been poisoned by the agency of his wife, the daughter of Llewellyn. The life of the bishop of Lincoln, too, was also attempted by the same means, and he was with difficulty recalled from the gates of death. In the same year, in the week before Whitsuntide, there fell storms of hail which exceeded the size of apples, killing the sheep ; and they were followed by continued rain.

A further complication goes back to Hugh of Cyfeiliog and the controversy around the legitimacy of Amicia. If Hugh did have another wife prior to Bertrade, then John would not have had quite so good a claim.

Aftermath

The Earldom reverted to the Crown in 1237 on the death of John the Scot (aged 30). However, the reversion was not as simple as most histories describe. William de Forz (Latinised as de Fortibus, sometimes spelt Deforce), 4th Earl of Albemarle, (died 1260) claimed that, as a Palatinate, it could not be divided, and his wife should get it as the oldest coheir. William got the title, but the court decided that the lands should be divided. However, he and his wife (Christina (d. 1246), daughter and co-heiress of Alan, Lord of Galloway) quitclaimed the earldom to Henry III in 1241 in exchange for modest lands elsewhere. So the last Earl of Chester may be described as William de Forz, and he held the title for four years, only a little less than John the Scot. William de Forz played a conspicuous part in the reign of Henry III of England, notably in the "Mad Parliament" of 1258. William's father died in 1241 on a ship on the Mediterranean, was described as "a feudal adventurer of the worst type" and was excommunicated in 1215 and also 1221!

The Earldom was formally annexed to the Crown in 1246 when the rest of the honour of Chester (the land) was bought from the rest of Ranulph's sisters by Henry III. King Henry III passed the Lordship of Chester, but not the title of Earl, to his son the Lord Edward in 1254, and as King Edward I he conferred the title and the lands of the Earldom first on son, Edward, the first English Prince of Wales. By that time the Earldom of Chester consisted of two counties: Cheshire and Flintshire.

Elen ferch Llywelyn re-married, her second husband being Sir Robert de Quincy (he had a brother, also called Robert, who married Hawise of Chester, Countess of Lincoln, sister and another co-heiress to Ranulf de Blondeville). Their daughter, another Hawise, was married to Baldwin Wake, Lord Wake of Lidel. Hawise and Baldwin’s granddaughter, the unfortunate Margaret Wake, was the mother of Joan of Kent, later Princess of Wales. Thus the blood of Llywelyn Fawr passed into the English royal family through Richard II - who was deposed in 1399 and briefly imprisoned at Chester Castle (see Royal Treasure for more).

Robin Hood's brother?

According to some, John had an older brother, Robert Le Scot, who some believe to be the dispossessed title holder of the earldom of 'Huntington' upon which Anthony Munday (1560-1633) based his "Robin Hood" plays and forever connected the Robin Hood ballads with the earldom of Huntingdon. Note, there are a number of locations titled Huntingdon or Huntington, one being lands which were owned largely by David, Earl of Huntingdon of Scotland who was John Le Scot's father. David of Scotland (Medieval Gaelic: Dabíd) (1152 – 17 June 1219) was a Scottish prince and the 8th Earl of Huntingdon. He was, until 1198, heir to the Scottish throne. Others are at Huntington in Herefordshire and of course Huntingdon in today's Cambridgeshire. The story is discussed in more detail under Ranulf de Blondeville.

A rather unexplored connection with Chester stems from the fact that David, Earl of Huntingdon endowed Lindores Abbey in Fife (1191). One of the symbols of the abbey was the "Bear and ragged staff", which may be the origin of the Bear and Billet inn sign at Chester. The Abbey ceased operation in 1559 but the "Bear and Ragged Staff" symbol survives on stonework and is still used on locally produced spirits.

The Sisters Legacy

John's heirs were the grand-daughters of Maud of Chester (the sister of Ranulf of Blundeville):

- Christiana, wife of William de Fortibus, Earl of Albemarle,

- Dervorguilla, wife of John de Balliol, and the two daughters of his eldest sister:

- Margaret, wife of Alan of Galloway, and his two younger sisters

- Isobel, wife of Robert de Bruce (mother of Robert de Bruce), and

- Ada, wife of Henry de Hastings.

Alan of Galloway was married three times. His first wife was a daughter of Roger de Lacy, Constable of Chester. His second marriage, which took place in 1209, was to Margaret (d. before 1228), eldest daughter of David, Earl of Huntingdon (d. 1219). His third marriage was to Rose (d. after 1237), daughter of Hugh de Lacy, Earl of Ulster (d. 1242). Alan had numerous children from his first two marriages, although only daughters reached adulthood. His eldest daughter from his first marriage, Helen, married Roger de Quincy (d. 1264). One daughter from his second marriage, Christina (or Christiana) (d. 1246), married William de Fortibus (d. 1260). Another daughter from his second marriage, Dervorguilla(d. 1290), married John de Balliol (d. 1314). Alan also had bastard son, Thomas, who survived into adulthood.

Three of the sisters of John were therefore the ancestors of Balliol, Bruce and John Hastings - all claimants to the Scottish throne on upon the death of Margaret, Maid of Norway, which caused the extinction of the legitimate line of "William the Lion" (John the Scot's uncle).

With the death of Alexander III of Scotland in 1286 without a male heir, the throne of Scotland had become the possession of the three-year old Margaret, Maid of Norway, the granddaughter of the King. As Margaret was never crowned or otherwise inaugurated, and never set foot on what was then Scots soil during her lifetime, there is, of course, some doubt about whether she should be regarded as a "Queen of Scots". In 1290 the "Guardians of Scotland", who had been appointed to govern the realm during the young Queen's minority, drew up the "Treaty of Birgham", a marriage contract between Margaret and the then five-year old Edward of Caernarvon, the heir to the English throne (later Edward II). The treaty contained the provision that although any offspring of this marriage would be heir to the crowns of both England and Scotland, the latter kingdom should be "separate, apart and free in itself without subjection to the English Kingdom". Unfortunately, Margaret died while returning to Scotland. Edward I then had a court set up to see which of the claimants should inherit the throne - it consisted of 104 auditors plus Edward himself as president (what a set-up!). David of Huntingdon's descendants were the primary candidates for the throne. The two most notable being John Balliol and Robert Bruce who represented descent through David's daughters Margaret and Isobel respectively. The arguments of these three descendants of Hugh de Kevelioc were as follows:

- John Hastings, an Englishman with extensive estates in Scotland, could not succeed to the throne by any of the normal rules governing feudal legacy and instead had his lawyers argue that Scotland was not a true kingdom at all, based, amongst other things, on the fact that Scots kings were traditionally neither crowned nor anointed. As such, by the normal rules of feudal law the kingdom should be split amongst the direct descendants of the co-heiresses of David I. Hastings was grandson of Ada, third daughter of David of Scotland, Earl of Huntingdon, who was a grandson of King David I therefore he had some support for this tenuous claim. Unsurprisingly, a court made up of Scots nobles rejected these arguments out of hand.

- John Balliol had the simplest, and thus by some measure the strongest claim of the four. By the tradition of primogeniture he was the rightful claimant, and that tradition had been followed in choosing heirs to the Scottish throne since King Edgar in 1097. He was a great-great-great-grandson of King David I through his mother and therefore one generation further than his main rival Robert Bruce, 5th Lord of Annandale, (grandfather of the future Robert the Bruce), being senior in genealogical primogeniture but not in proximity of blood. He argued that the other Scottish claimants (including Bruce) had already tacitly acknowledged the tradition of primogeniture in allowing Margaret of Norway to claim the throne. Balliol also argued that the Kingdom of Scotland was, as royal estate, indivisible as an entity. This was necessary to prevent the kingdom being split equally amongst the heirs as Hastings was suggesting should be done.

- Robert Bruce was the next in line to the throne according to proximity of blood. Robert was son of Robert Bruce, 4th Lord of Annandale and Isobel of Huntingdon, the second daughter of David of Scotland, 8th Earl of Huntingdon and Matilda de Kevilloc of Chester. David in turn was the son of Henry of Scotland, Earl of Huntingdon and Northumberland and Ada de Warenne; Henry's parents were King David I of Scotland and Maud of Northumberland. As such, his arguments were that this was a more suitable way to govern the succession than primogeniture. His lawyers suggested that this was the case in most successions and as such had become something of a 'natural law'. Unfortunately for Bruce, the Scots tradition for the preceding 200 years had been demonstrably different, relying on primogeniture instead. His grandson was Robert the Bruce who became king of Scots from 1306 until his death in 1329.

Edward I gave judgement on November 17, 1292 in favour of John Balliol. and he was inaugurated accordingly king of Scotland at Scone, 30 November 1292, St. Andrew's Day. Edward I, had coerced recognition as "Lord Paramount of Scotland", the feudal superior of the realm, and steadily undermined John's authority. Edward demanded homage to be paid towards himself, legal authority over the Scottish King in any disputes brought against him by his own subjects, contribution towards the costs for the defence of England, and military support in his war against France. He treated Scotland as a feudal vassal state, and repeatedly humiliated the new king. Tiring of their deeply compromised king, the direction of affairs was allegedly taken out of his hands by the leading men of the kingdom, who appointed a council of twelve at Stirling in July 1295. These men concluded a treaty of mutual assistance with France, which became known as the "Auld Alliance". In retaliation Edward I invaded, commencing the Wars of Scottish Independence.

John the Scot would have had to have lived to the age of 85 to have been around in 1292. If he had a son, that son (whose mother would have been Elen ferch Llywelyn, herself daughter of Llywelyn the Great), or possibly a grandson, would have had a legitimate claim to the throne of Scotland as well as the Earldom of Chester - and very good Welsh connections. Had the Earldom of Chester continued in this manner, Edward I would have faced serious problems in both his attempts to conquer Wales and his wars with Scotland.

Sources and links

Related Pages

- Earls of Chester: a general overview;

- Ranulf de Blondeville: the previous Earl;

- Joan, Lady of Wales;

Online Sources

- "Patrick Delaforce Family History Research Chapter 38".;

- More family history for the Earls of Chester;

- Lands of the Scottish Kings;

- Kingship, Rebellion and Political Culture: England and Germany, C.1215 - C.1250;

- A History of England, 1815-1939: James Ramsay Montagu Butler · 1960;

- The Minority of Henry III: By David A. Carpenter · 1990;

- William Marshal: Knight-Errant, Baron, and Regent of England, By Sidney Painter · 2020

- Henry III: The Rise to Power and Personal Rule, 1207-1258, By David Carpenter · 2020;

- King John, Henry III and England’s Lost Civil War: By John Paul Davis · 2021;

- ARISTOCRATIC FEMALE INHERITANCE AND PROPERTY HOLDING IN THIRTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLAND;

- Cheshire and the crusades;