Cuppin Street

Historic Cuppin Street

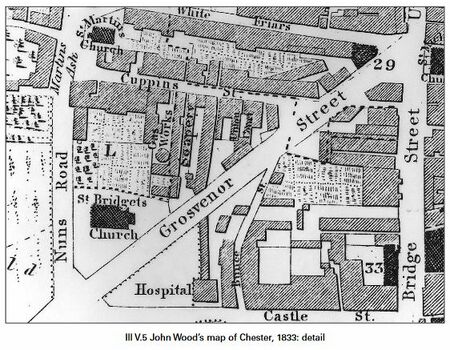

The origins of the name of Cuppin Street (formerly "Cupping Lane") has been the subject of much discussion. Some claim it comes from the location of drinking ("cupping") houses, while others claim it is a contraction of "Jacobin". Cuppin Street used to extend to Nicholas Street, but was sealed off when the ring-road was constructed in the 1960's.

Hemingway (1831) descibes it as follows:

- "Cuppin's street so called as tradition says from licensed bagnios or cupping houses being situated here is immediately on the south side of the buildings just mentioned: it is cut in two by the intersection of the new street is but narrow with many indifferent houses and terminates at Martin's Ash near St Martin's church."

In 2017 the bones of men, women, and children were excavated in an archaeological dig near the site of the Franciscan church in Chester, on Cuppin Street. 20 sets of bones were re-buried in Pantasaph, Flintshire - at the friary which founded the current Franciscan friary in Chester. The graveyard here is apparently quite extensive. In the 1990's work had to be stopped on the construction of the nearby new Magistrates Court when a supposed "plague pit" was discovered. There were also stories circulating at that time of "witches" being found buried face-down in coffins filled with tar.

A "sugar house"

On the south side of Cuppins Lane once stood five cottages which by 1740 had been demolished, and the land, in the ownership of Geo Hope and already used as a timber yard by Thomas Hincks, was let to John Kelsall, and then in early 1741 sold to Geo Prescott. Over the next decade or so the land was variously let to Wm Buckley and later his widow & Mr Linney, and Tho Adams coal merchants, before Thomas Prescott, son, heir and executor of the late George, sold it to Benjamin Wilson a sugarbaker from Liverpool in 1752/3.

The building of the three pan sugar house in Cuppins Lane was probably begun in early 1755, as a covenant to the sale of the land, dated 26 April 1753, stated that if any building being erected for the purpose of refining sugar within 3 yrs of 20 July 1752, then Benjamin Wilson should pay Thomas Prescott £50 within one month of building commencing ... Thomas Prescott's receipt for the £50 was dated 15 Feb 1755. Whether Wilson began the sugar house by himself is not known, but in 1756 he and his wife made an agreement between themselves and John Hincks of Chester and Joseph Manesty of Liverpool for the running of the business, and on 21 Mar 1757 Articles of Co-partnership were signed by Wilson, Hincks and Manesty to carry out the trade of sugar refining in premises purchased by them in the name of Benjamin Wilson from Thomas Prescott. Manesty had a half share, with Hincks and Wilson taking a quarter share, but at that time they were still short of some £16,000 funds for joint stock. The partnership does not appear to have got off to a good start, for by the beginning of 1758 questions were being asked by Hincks of Manesty's methods of buying sugar, and when in March a large bill for 55 hogsheads of raw sugar valued at over £1344 was presented by Francis Perkins of Liverpool, Wilson accused Manesty of paying too high a price for sugar, and Manesty complained in turn that there was no money available to pay the "Excise Man" for an earlier 50 hogshead order. By 1764 Manesty had been declared bankrupt and wanted whatever remained of his share back.

Wilson died in 1767. He left his estate to his wife including his interest in the sugar house, leaving instructions that after her death it should be valued and sold. The accounts at the time showed that after all bills and bonds had been paid there was just £1461 9s 11d to be shared equally between Hincks and Benjamin Wilson's executors. John Hinks, the sole surviving partner died in 1772, by which time the sugar house had made, and spent, around £40,000 profits (and run up over £16,000 in debts). Hink's Widow (Arbella Cowper) appears to have continued with the business and was later joined by her son. More money was invested, but they appear to have gone bust around 1778.

The Gasworks

The Chester Gaslight Company was formed in 1817 by Deed of Settlement and remained a non-statutory company. Its works were in Cuppin St and were built by the famous gas engineer Samuel Clegg. Gasworks were noted for their foul smell and generally located in the poorest metropolitan areas.The process used was the carbonization and partial pyrolysis of coal. The off gases liberated in the high-temperature carbonization (coking) of coal in coke ovens were collected, washed and used as fuel. The main use of the gas was street-lighting. The illuminating power of a gas was related to amount of soot-forming hydrocarbons (“illuminants”) dissolved in it. These hydrocarbons gave the gas flame its characteristic bright yellow color. Gas works would typically use oily bituminous coals as feedstock. These coals would give off large amounts of volatile hydrocarbons into the coal gas, but would leave behind a crumbly, low-quality coke.

The streets around Cuppin Street were first lit in 1818 and the main city by 1830. In 1837 the city council took over responsibility for street lighting.

Pressure from the Chester Watch Committee and public dissatisfaction with costs led to a number of attempts to establish a rival undertaking in the town. An attempt to threaten the company with a rival undertaking was beaten off in 1844, but continuous agitation forced the company to cut prices and modernize the system. A complete reorganisation of the works in 1845 attempted to inprove efficiency and bring down costs. In 1850 another rival company tried to establish itself - the Chester Gas Consumers Co, though this failed to raise enough capital to launch properly. In 1851 an engineer from Birkenhead gasworks, Samuel Highfield, established a second company and built a gasworks, by the River Dee, at the Roodee on the outskirts of Chester. Highfield was awarded the contract for street lighting in 1853.

The Roodee Gas Co was soon sold on and by 1855 the two companies began negotiations to amalgamate. The Chester United Gas Co was formed in August 1856 with the chairman, E Salisbury, formerly the chairman of the Roodee Gas Co. The council was unhappy with the re-established monopoly but it did bring about the closure of the Cuppin Street works, which was causing serious pollution. The Roodee works were rebuilt in 1880 and a series of Acts of Parliament extended the area of supply to surrounding villages. In 1949, the company was nationalised and vested in the Wirral Group of the NWGB. The Roodee works closed in 1966 after pipelines had been laid to connect west Cheshire with Lancashire, north Wales, and the works at Ellesmere Port.

Soap Boiler

The Hodson and Witter soap factory in Cuppin Street had a Royal Warrant to supply soap products to queen Victoria. Although Hemingway (1831) describes the premises as "extensive", there is little recorded about the business other then its mention in trade directories (Pigot's 1822). It is not mentioned in the 1789 or 1857 directories. As well as the gasworks causing pollution, a soap-boiler would also as the process would have involved boiling up tallow with alkali to yeild glycerol and soap, leading to noxious smells and effluent.

The Star

The Star was an inn on Cuppin Street, and like many inns in Chester its stabling became a slum court after the advent of the railways. In March 1903, a case of smallpox was detected at 1, Star-court and caused some alarm in Chester.

Buildings

The eastern end of Cuppin Street houses several restaurants, the central section has the friary to the south and housing to the north and the west end has offices. Some of the restaurant buildings appear to have been warehouses with access doors (now converted to windows) to the front of the buildings, and a projecting gable where the hoist mechanism would have been.

North Side

16 and 18

Pair of small town houses. Early C19. Pale brown brick, Flemish bond to front; grey slate roof, ridge parallel with front. 3 storeys, of one bay per house. Painted stone plinth; recessed sashes with painted stone sills and wedge lintels.

20 and 22

Pair of town houses, possibly formed by the sub-division of a larger house. Early C18, altered. Brown brick in Flemish bond to front; each house has a grey slate roof with ridges at right-angles to front.

South Side

1, 3 and 5 Cuppin Street

4 small town houses, now 2 town houses and a restaurant which occupies No.14 Grosvenor Street and No.1 Cuppin Street. Brown Flemish bond brick to Cuppin Street and west end to Union Place.

Union Place

The only surviving "court buildings" in Chester. The houses are tiny and probably date from the 1830s. Brown brick in Flemish bond to front and English garden wall bond to ends; hipped grey slate roof. 3 storeys, each former house of one bay. Painted sandstone plinth; one sandstone step to each door; doorcases with simple pilasters, friezes and cornices.

The Friary

Friars are different from monks in that they are called to live the evangelical counsels (vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience) in service to society, rather than through cloistered asceticism and devotion. Whereas monks live in a self-sufficient community, friars work among laypeople and are supported by donations or other charitable support. A monk or nun makes their vows and commits to a particular community in a particular place. Friars commit to a community spread across a wider geographical area known as a province, and so they will typically move around, spending time in different houses of the community within their province. More on the friary and it's church can be found on the Grosvenor Street page. In the 1980s the 1876 friary building on Grosvenor Street was disposed of (it became a hostel for homeless men) and the friars moved into the smaller modern building on Cuppin Street.

The School

The school was built (1882) and opened in 1883 to serve the Roman Catholic parish of St. Francis. Children living in the parish who had previously attended St. Werburgh's Schools were transferred here (see J.C. Fowler, The Development of Elementary Education in Chester, 1800-1902, 1968, p. 165). A surviving log book records that in 1909 the Education Committee refused to recognise the school as a public elementary school and that it was only recognised when it acquired enough land for a playground in 1922. It continued as a junior and infant school until September 1972 when Chester schools were reorganised into first, middle and high schools. As a result of this reorganisation St. Francis' School became an annexe to St. Clare's First and Middle School, which was opened at Hawthorn Road, Lache, in September 1972.

The School is now the Unity Centre, West Cheshire's multicultural hub. It co-locates a variety of small BME community organisations who run their own activities from the Centre such as reiki, knit and natter sessions and Indian dancing. The Chester Diwali festival of light (late October) is organised from here: one of the most popular Hindu festivals, it signifies the victory of light over darkness, good over evil, knowledge over ignorance, and hope over despair.

An important political change may have been kicked-off in this building. First some background: the English Protestant Reformation was imposed by the English Crown, and submission to its essential points was exacted by the State with post-Reformation oaths which were effectively anti-catholic. With some solemnity, by oath, test, or formal declaration, English churchmen and others were required to assent to the religious changes, starting in the 16th Century, and continuing through to the 20th Century.

The Cheshire Observer of 9th March 1901 reported:

- "A special general meeting of St. Francis Catholic Men's Society was held in the Franciscan Schools, Cuppin-street, on Sunday. The president of the society, Mr. William Jarvis. was in the chair. The following resolution was proposed from the chair: "Resolved, that we, the Catholic Men's Society of Chester, in general meeting Assembled, are of opinion that Parliament should take immediate steps to abolish that portion of the declaration or oath of accession dealing with the Roman Catholic faith, as we consider it is not only opposed to the spirit of the age in which we live, but that it is offensive and extremely insulting to the members of the Catholic religion. Also we respectfully call upon the other branches of the Y.M.S. of Great Britain to do likewise." The resolution was seconded by Bro. J. C. Dalton, and supported by the Rev. Fathers Mulcahy (St. Werburgh's), Dominic, OJS.F.C., and Wilfrid, O.S.F.C. (St. Francis's). On being put to the meeting the resolution was carried with acclamation. Copies of the resolution have 'been forwarded to Mr. Yerburgh and Mr. John Redmond."

Robert Yerburgh was the MP for Chester. John Redmond (1 September 1856 – 6 March 1918) was an Irish nationalist politician, barrister, and MP in the British House of Commons. He was best known as leader of the moderate Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) from 1900 until his death in 1918. He was also leader of the paramilitary organisation the Irish National Volunteers (INV). In 1904, 1905, and 1908 bills or motions to remove the declaration were introduced by Lord Braye, Lord Grey, Lord Llandaff, the Duke of Norfolk, and Mr. Redmond, but without the desired effect. After the death of King Edward VII, however, King George V is believed to have urged the Government to bring in a repealing Act, which was to become the "Accession Declaration Act 1910". This was done and public opinion, after some wavering, finally declared itself strongly on the side of the Bill, which was carried through both Houses by large majorities, and received Royal Assent on 3 August 1910, thus removing the last anti-Catholic oath or declaration from the English Constitution. Whether the movement which led to this change started in Chester is unclear, but it would fitting if it did, given the location of the Unity Centre in this very building.