Thomas Brassey

Thomas Brassey was the consumate organiser of construction for much of the infrastructure of the Victorian age. He was active in the development of steamships, mines, locomotive factories, marine telegraphy, water supply and sewage systems. Largely unknown to the general public, he now (as of 2025) has a statue outside of Chester Station.

Life

Thomas Brassey (1805-1870) was born near Chester, a farmer’s son. Thomas received a solid education in Chester. After schooling and at age 16 Brassey obtained an apprenticeship with surveyor William Lawton and eventually took over the business as a Civil Engineering supply and Contracting Company. The local surveys he conducted throughout the north of Wales and England had provided the foundations of his career as a railway surveyor and contractor. When he needed money he initially borrowed from his father, but as things progressed he opened an account in Chester and this enabled him to expand – from then on it appears that all his money was self generated.

His career took him into railway construction where he is credited with building one-third of the railways in this country, three-quarters of those in France and no less than 1 in 20 miles of the total world’s railways. Much nearer home as a civil engineering contractor he built Chester Station, the Queen Hotel opposite and the Cefn Mawr Viaduct. Brassey’s successful juggling of multiple contracts in far-flung parts of the empire rested not only on shrewd financial management (enabling him to survive the financial crashes in the rail industry during the 1840s and 1860s) but also on his ability to raise and run a huge labor force. His workers generally respected Brassey because he believed well-fed and well-rested workers were more efficient and produced better results than laborers who were poorly paid and fed. At the peak of his career he employed upwards of 85,000 men spread over the world and is said to have had as much influence on the world’s development as Alexander the Great.

There are many web resources available on Brassey so this article concentrates on those elements connected to Cheshire and Chester which might be of interest to the Cestrian and visitor alike.

Early Life and Background

Thomas Brassey was the eldest son of John Brassey, a prosperous farmer, and his wife Elizabeth, and member of a Brassey family that had been living at Manor Farm in Buerton, a small settlement near Aldford, 6 miles (10 km) south of Chester, from at least 1663. It is claimed that for the previous "nearly six centuries" the family lived at Bulkeley, near Malpas. They may have been descended from (or associated with) the Brescy family who were associated with Bulkeley around 1300.

In 1805 Buerton was a chapelry of St Oswald in Chester and while some sources state that he was born in the parish of Aldford this did not exist until 1866. An Elizabeth Brassey is listed as the occupier of serveral fields near Bruera in the 1840's tithe maps, the actual owner being the Duke of Westminster. Apparently the Brassey's also owned some land of their own. There are two Buerton's in Cheshire and Brassey was from the smaller of the two (which is not even marked on modern maps), and where there is little to see that any kind of hamlet ever existed here.

Brassey was educated at home until the age of 12, and thereafter went to the King's School in Chester. After leaving school c.1820 at age 16, Thomas Brassey went to work for William Lawton, a surveyor and land agent in and around the Cheshire area. Lawton was at that time, and for many years had been, the agent of Francis Richard Price, of Bryn-y-pys, Overton, Flintshire. Price was the Lord of the Manor of Birkenhead, a major landowner and developer in Birkenhead after 1823 and involved with a scheme of Telford's c.1828 to build a ship canal across the Wirral from the mouth of the Dee to Wallasey Pool. The ship canal was never built.

Brassey’s first job in his apprenticeship as a trainee surveyor was to work with a surveyor named Penson of Oswestry, who was employed under the direction of Thomas Telford on the London to Holyhead road from Shrewsbury to Holyhead. The name Penson is also associated with architecture in Chester, so is there a link with this earlier Penson? A Thomas Penson the elder (c.1760–1824), had been the county surveyor for Flintshire from 1810 to 1814, but had been dismissed when the bridge at Overton-on-Dee collapsed in 1811: his son Thomas the younger (c. 1790 – 1859) was a pupil of the architect and bridge designer Thomas Harrison of Chester. There is already a link here as the same Francis Richard Price as mentioned above was the owner of the Overton Cottage where the Junior Penson lived during the 1814 construction of the new Overton Bridge. A third Penson was Thomas Mainwaring Penson (1817-1864) who was born in Oswestry, and was educated at Oswestry School. He and his brother, Richard Kyrke Penson (1816-1886), then trained in their father's practice. The elder brother, Richard, seems to be the better qualified and more prolific of the two. T.M. Penson laid out Chester's Overleigh Cemetery in 1848–50 and is credited with pioneering the Black-and-white Revival (vernacular, half-timbered or Mock Tudor) style in the city during the 1850s. His other notable buildings in Chester were designed both in Black-and-white Revival and in other styles. They include Crypt Chambers (1858) in Eastgate Street, which is in Gothic Revival style, the Queen Hotel (1860–61) opposite Chester Station, which is Italianate, and the Grosvenor Hotel (1863–86). The middle Penson is a candidate for the surveyor of the future A5 that Brassey worked with, but further research is needed to establish this.

Brassey was eventually put in charge of William Lawton's Birkenhead office and moved there at the age of 21 (1826) where he soon became a partner in the business. After the death of Lawton he became the sole partner. He would live there for eight years. Thomas Brassey first lived in Whetstone Lane, Birkenhead and later in a house he built himself in Park Road South, Claughton (although it would have has a different name: Birkenhead Park didn't exist at the time). The owner of the Birkenhead Brewery Company, Henry Kelsall Aspinall, knew Thomas Brassey very well and described him thus:

- “A gentleman in the fullest sense of the word; quiet, simply living and simple hearted, amiable and kind to a degree”.

At the same time Brassey worked for the Stanley family, managing the commercially developing Stourton (Storeton) Quarries on their estate. It was there that he first met George Stephenson who was looking for stone for the Sankey Viaduct (built 1828-30). The Storeton quarries had a tramway which carried stone down to the Mersey, and it appears that the weight of the loaded "cars" going downhill was used to haul the empty cars back up. It is not clear whether this was Brassey's idea, Stephenson's or that of another. Nothing of this tramway remains.

Both Lawton and Brassey envisaged the expansion of Birkenhead and so Brassey built himself a brick works and lime kilns, borrowing the funds for this from his father. In 1829, with Lawton, Brassey was contracted to re-build a small bridge at Saughall Massie. The Bridge was to county bridgemaster Samuel Fowls' design, being quite detailed in its requirements, with stone mandated to be obtained from the old bridge and new stone from the Bidston Hill Quarry. A new approach road was also built including sandstone walls on either side. Some of the original walls still remain and can be seen at the lower level, having a thin mortar line between the stones. One theory as to why the bridge was built (which may be little more than legend) is that the area of marsh and moss along the Wirral coast was habitually used by Wreckers and that without the bridge the area was isolated and lawless. However the records clearly show that there was a previous bridge there.

1831 (December 20th or 26th depending on the source) Brassey was married at Birkenhead to Maria Farrington Harrison, the sister of engineer George Harrison. She seems to have encouraged her husband to expand into railway contracting. Her fluent command of French would also be of great benefit during his work on the French railways.

Brassey's habit for being in the right place at the right time again showed in 1830/31 when he buit his first railway to carry heavy loads of salt from the Cheshire salt mines in and around Marston near where the Lion Salt Works Museum now stands. He again appears to have been funded by his father. Even if the Storeton tramway was built later, Brassey would been aware of the Flaybrick Hill tramway in Birkenhead, which was in use by 1819 (six years before that at Stockton and Darlington) and appears on Bryant's map of Cheshire published in that year, marked as a "Rail Road".

The list of Brassey's contracts in "Life and Labours of Mr Brassey" by Sir Arthur Helps (1872) gives the 'Branborough' (Tranmere to Bromborough) road in 1834 as his first, but clearly the bridge at Saughall Massie (1829) and the Marston Rock Salt Rail Road (1830) preceded that. What is clear from this is that even from his twenties Brassey was demonstrating an ability to manage the construction side of infrastructure projects. The mines at Marston now lie under Neuman's Flash, which with the adjacent Ashton's Flash are now part of Northwich Woodlands country park. No traces remain of either rock-salt pits or the railroad.

Railways

In 1835 Brassey, at the age of 30, submitted a tender for building the Penkridge Viaduct, between Stafford and Wolverhampton, together with 10 miles (16 km) of track. Since Saughall Massie and the Marston Salt Railroad, he had tried unsuccessfuly to tender for the Dutton Viaduct, but did to win the bid. Brassey was not an engineer, but rather took the role of a project manager and contractor, who organised the workforce and the supply of materials. The tender for the work at Penkridge was accepted, the work was successfully completed, and the viaduct opened in 1837. Initially the engineer for the line was George Stephenson, but he was replaced by Joseph Locke, Stephenson's pupil and assistant. During this time Brassey moved to Stafford. Penkridge Viaduct still stands and carries trains on the West Coast Main Line. On completion of the Grand Junction Railway, Locke moved on to design part of the London and Southampton Railway and encouraged Brassey to submit a tender, which was accepted. Brassey undertook work on the section of the railway between Basingstoke and Winchester, and on other parts of the line. The following year Brassey won contracts to build the Chester and Crewe Railway with Robert Stephenson as engineer and, with Locke as the engineer, the Glasgow, Paisley and Greenock Railway and the Sheffield and Manchester Railway. By the end of the "railway mania", Brassey had built one-third of all the railways in Britain.

By 1841 Brassey’s name was becoming widely known and he started building railways outside of Britain – the first being the 82 mile Paris to Rouen railway – the first railway in France and for which French contractors were too expensive. By 1848 Brassey had built three quarters of the entire French railway system. When the Paris to Rouen railway was opened in May 1843 Brassey gave an open air banquet where 600 of his workmen sat down. He was renowned for taking good care of his workforce. A whole ox was roasted by three French chefs and the French became so agitated at the prospect of 600 British navvies going on the rampage that they ringed the field with their cavalry. In the same year he built Chester Station to the design of architect Francis Thompson with ornamental stonework by sculptor John Thomas. The railway engineers were Robert Stephenson and Charles Heard Wild.

Brassey was well-known for having few or no administrative staff, holding masses of information in his head and dealing with correspondence himself. He would subcontract to others with a fixed fee, allowing them to keep any monies not spent, but he was very particular about quality. If costs ran over the job would be completed out of his own pocket. In January 1846, during the building of the Rouen and Le Havre line, one of the few major structural disasters of Brassey's career occurred, the collapse of the Barentin Viaduct. The viaduct was built of brick at a cost of about £50,000 and was 100 feet (30 m) high. The reason for the collapse was never established, but a possible cause was the nature of the lime used to make the mortar. The contract stipulated that this had to be obtained locally, and the collapse occurred after a few days of heavy rain. Brassey rebuilt the viaduct at his own expense, this time using lime of his own choice. The rebuilt viaduct still stands and is in use today.

By 1852 Brassey had teamed up with Sir Morton Peto, the civil engineer and contractor, and Peto's son-in-law, Edward Betts, to form a loose association of Peto, Brassey and Betts. The team were involved with the Canada Dock (to a design by Jesse Hartley) in Birkenhead in 1852, so they could lay the Grand Trunk Railway over the 540 miles from Quebec to Lake Huron. Much of the material was made at the Canada Works in Birkenhead. The works constructed the metal parts for the original Victoria Bridge crossing the St. Lawrence: when completed, it was the longest bridge in the world. The line was an engineering success but a financial failure, with the contractors losing £1 million. Brassey and his associates also turned their attention to the Crimea in the late winter of 1854. On November 30, the company suggested the Government build a 39-mile Grand Crimean Central Railway from Balaclava to all parts of the front. By late December, men were leaving Birkenhead for the Crimea. In six weeks, the railway was finished with the contractors having worked "at cost". By March, 1,000 tons of shot and shell, 3,600 tons of clothing and medical supplies and other goods had reached the men. Soon 17 engines were carrying freight up the line. After the end of the war the track was sold and removed.

Queen Hotel

The Queen Hotel, located directly across from the Railway Station at the end of City Road, was designed by Penson and opened on the 21st April 1860, costing £29,000.00. A novel feature of the hotel were two iron lattice-work towers which could be ascended to obtain a view of Chester. As noted above the contractor for the job was Brassey. It's promotions state that it was:

- "built in the Italian style upon a beautiful piece of ground with sumptuous furnishings, a beautiful garden and offering the quietest and most spacious first class Hotel in Chester" (21st July, 1860).

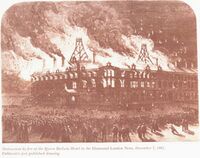

The following year, in December 1861, the hotel was gutted by a major fire. Apparently, back in 59/60 the builders had put a wooden joist through the flue of one of the chimneys and over the course of the following year this slowly burned away until it could ignite the entire building. Randolph Caldecott's illustration of the Queen Hotel fire (his first published work) shows not only how major the fire was, but also shows the latticed "observation towers" that (unfortunately) were not rebuilt after the fire. Early guidebooks (pre-fire) refer to the Queen Hotel having a "patented heating system" in the basement, but this is not mentioned afterwards: maybe it also had something to do with the fire?

Great Eastern

The Eastern Steam Navigation Company was formed in January 1851 with the intention of exploiting the increase in trade and emigration to Australia after the discovery of gold there. To make this a viable proposition they needed a subsidy in the form of a mail contract from the GPO, for which they tendered. In March 1852, against the advice of a House of Commons Committee set up to look into the awarding of mail contracts, the Government awarded both to P&O, although the ESN tender was lower.

Finding themselves in the position of having a company without a purpose, they were in effect open to offers. Brunel wrote a paper on his idea of building a ship capable of sailing to and from Australia without the need to refuel on route and sent it to ESN. He was invited to present his ideas to the board but was unable to attend so John Scott Russell took his place. A committee was set up to look into the idea and they reported in favour and the scheme was adopted at a board meeting held in July 1852. Brunel was appointed Engineer and tenders were invited for the hull, paddle engines and screw engines.

Nearly 19,000 gross registered tons, six masts, five funnels, four decks, side-mounted paddle-wheels, and a single propellor – the SS Great Eastern was 692 feet in length and would not be surpassed in length until the launch of the RMS Oceanic 40 years later. Her length is commemorated by being marked-out on the City Walls of Chester. The hull was divided into ten watertight compartments. She could carry 4,000 passengers (800 first class, 2,000 second, 1,200 third) and achieve a speed of about 15 knots (or 27.7 kilometres per hour) if the paddle-wheels and propellor were used together.

Brassey became involved with the ship at an early stage (1857) and would remain a bond-holder for many years. Construction and launch of Great Eastern had brought the Eastern Steam Navigation Company close to bankruptcy and to prevent this happening and creditors seizing the ship a new company the "Great Ship Company" was formed with a capital of £340,000. They bought the Great Eastern for £160,000, leaving sufficient funds for the fitting out. ESNC shareholders got about 10% of the value of their share in new GSC shares.

Her maiden voyage to America began on 17 June 1860, by which time the controling ownership had already changed several times. By 1864 she was laid-up due to high operating costs. In January 1864, it was announced that the ship would be auctioned off. During the auction, four members of the company board of directors bid $25,000 for the ship and won it, thus acquiring personal control of the vessel. Daniel Gooch, a director of the Telegraph Construction & Maintenance Company (Telcon), had seen an opportunity. Gooch had convinced John Pender and Thomas Brassey to invest in the purchase of the erstwhile passenger ship. They formed a company, the Great Eastern Steamship Company, and chartered the Great Eastern to Telcon.

The group then allowed the ship company to go bankrupt, thus separating the ship from the now defunct shipping company and divesting many smaller stockholders. Three cable tanks were fitted into the ship’s large hull, with enough space for 2,489 nautical miles (or 4,609.6 kilometres) of telegraph cable. The distance between Ireland and Newfoundland was (and still is) just under 2,000 miles, or about 3,200 kilometres. These cable tanks were flooded so the cable could be kept immersed in water. The ship was then contracted out to Cyrus Field, an American financier, who intended to use it to lay underwater cables. It is sometimes said that Great Eastern laid the first transatlantic cable, which is not entirely accurate: Field had laid an earlier cable in 1854-58. The cable was destroyed after three weeks when Wildman Whitehouse applied excessive voltage to it while trying to achieve faster operation. There is a further Chester connexion here: one of the investors in the original cable was Charles W.H. Pickering (1815-1881) a principal of a large international banking firm (John Henry Schroeder & Company of Hamburg). Pickering apparenly had links to Hoole where there is a street said to be named after him and his message was the first to be sent over the original cable. See "Time" for more on this.

Great Eastern's owners developed a business model whereby they would rent out the ship as a cable layer in exchange for shares in cable companies, ensuring that if Great Eastern succeeded in laying cables, the unprofitable ship could be personally lucrative for her owners. The Great Eastern made two attempts to lay the transatlantic submarine cable, first in 1865 and then again in 1866. This second attempt succeeded.

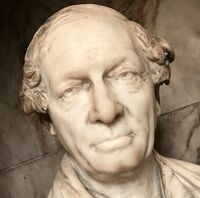

His Statue, and other memorials

In 2025 a statue of Brassey was errected outside of Chester Station. It features the c.40 year old Brassey looking at a map. which seems to be a published folded one. Which actual map it is might be open to some debate. Andrew Bryant's map of Cheshire was published in 1831. Bryant published a dozen county maps from 1822, before going out of business in 1835 due to the increasing difficulty in competing with the government-supported Ordnance Survey. Other maps of the same time include that of Swire and Hutchings (1830) which shows Buerton, Brassey's birthplace. The printing style of the cartouche on the map seems to be that of George Frederick Cruchley (1797-1880) an English map-maker, engraver and publisher based in London. Cruchley started in 1823, selling primarily maps of London, which were of a good quality and very popular. However, in 1844/50 he acquired the working stock of plates from the old firm of George and John Cary, and proceded to use these via lithographic transfers to produce very cheap but out of date maps of the English Counties and country, only updating them for railways (and that somewhat speculatively at times - several times adding "proposed" lines that were not built).

Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900 writes of Brassey:

- Brassey is described by his biographer as a man almost without faults. The only defect mentioned was a difficulty in saying no, which led to involvement in some disastrous undertakings. His ruling passion was the execution of great works of the highest utility with punctuality and thoroughness. He possessed the highest business talent, power of calculation, and skill in organisation. He knew how to trust subordinates and distribute responsibility. He was beloved by the men he employed, and made the fortunes of many subordinates who rose by his help. He was liberal, and indifferent to honours and to money, though he made a large fortune without suspicion of unfair dealing. His domestic life was perfect. Although his education had been scanty, and he never acquired any command of foreign languages, he was a man of great natural refinement, with a keen taste for art and for natural beauty. His courtesy and shrewdness made him an excellent diplomatist, and in all his undertakings he was on the most cordial terms with his associates. Brassey's experience in the employment of labourers of different races was enormous, and he made many interesting observations, of which some account is given in his life. Sir T. Brassey's 'Work and Wages' (1872) embodies some information derived from this and other sources.

There is a link to Arthur Helps' biography below. As written on Wikipedia:

- ..it is not easy to be objective about the nature of Thomas Brassey's character because the earliest biography by Helps was commissioned by the Brassey family and the latest, rather short, biography was written by his great-great-grandson, Tom Stacey. There is virtually no remaining material of value to a biographer available today. There is no private correspondence, there are no diaries and none of his personal reminiscences.

On 8 December 1870 Thomas Brassey died from a brain haemorrhage in the Victoria Hotel, St Leonards and was buried in the churchyard of St Laurence's Church, Catsfield, Sussex where a memorial stone has been erected. In 1870 during the restoration by George Gilbert Scott, the south aisle of the Cathedral was shortened and its east end was converted into the St. Erasmus (St Elmoo) Chapel. In 1879 Brassey's sons created a memorial to their parents in the chapel. This consists of a mosaic, and a bust of their father to the north of the altar. The wall mosaic was designed by J. R. Clayton and executed by Antonio Salviati. The memorial is by Sir Arthur Blomfield and the bust by Michael Wagmüller. There is also a bust of Brassey in Chester's Grosvenor Museum and plaques to his memory in Chester Station. Streets named after him in Chester include Thomas Brassey Close (off Lightfoot Street). By the waterworks in Boughton, there are three adjacent street names which spell 'Lord' 'Brassey' of 'Bulkeley' (Brassey was never a lord, but his son also Thomas became Baron Brassey, of Bulkeley in 1886). In April 2007 a plaque was placed on Brassey's first bridge at Saughall Massie. In the village of Bulkeley is a tree called the "Brassey Oak" on land once owned by the Brassey family. This was planted to celebrate Thomas' 40th birthday in 1845. In 2019 a blue plaque was installed by Conservation Areas Wirral on the remaining structure of his Canada Works building in Beaufort Road, now part of the Wirral Waters area in Birkenhead.

Works Near Chester

Brassey was involved as contractor in several construction works within easy distance of Chester, many of which are still in use and might be missed by Cestrians and visitors alike. Wikipedia has a longer list including works elsewhere. Chester Station and the Queen Hotel are mentioned in the body of the text. The politics and economics of early railways at Chester are very complicated.

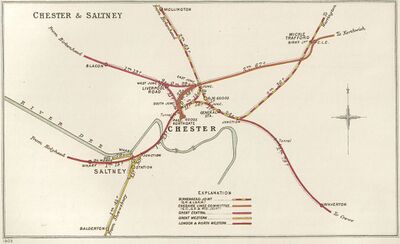

- Chester and Crewe Railway: authorised in 1837 by the Chester and Crewe Railway Act this railway is very familiar to anyone making regular trips from Chester to London. The engineer was Robert Stephenson. It roughly follows the canal route from Chester along the Gowy via Beeston Castle.

- Chester and Holyhead Railway: this was conceived to improve transmission of government dispatches between London and Ireland, as well as ordinary railway objectives. In the 1840s the partnership of Brassey, Mackenzie and Stephenson obtained two contracts for 31 miles of construction on the Chester and Holyhead Railway. Its overall construction was hugely expensive, chiefly due to the cost of building the Britannia Tubular Bridge over the Menai Strait. For further information see: Chester and Ireland.

- Gobowen Station: designed by Thomas Mainwaring Penson and opened in 1848.

- Chirk Railway Viaduct: built between 1846 and 1848. To the east, the Chirk Aqueduct lies parallel to the railway viaduct.

- Cefn Mawr viaduct near Ruabon. The viaduct was designed by Henry Robertson, chief engineer of the Shrewsbury and Chester Railway, to carry the railway line across the River Dee between Newbridge and Cefn-bychan. It is around a mile downstream of Pontcysyllte Aqueduct. Building commenced in 1846, with Thomas Brassey as the general contractor. At the time of opening (1848) it was claimed to be the longest viaduct in Britain. The area around Cefn Mawr was important in the early industrial revolution.

- Ruabon to Corwen line: The Llangollen Railway operates on part of the former Ruabon to Barmouth line between Llangollen and Corwen (1860)

- Runcorn Railway Bridge (stonework). An engraved stone plaque on the northerly portal records that the main contractor was Brassey & Ogilvie and the ironworks were manufactured by Cochrane Grove & Co. The official name of the bridge has been a subject of debate. Locally, it has been called the Queen Ethelfleda Viaduct, but is also called the Britannia Bridge. It has been claimed that it was named after Æthelflæd, a ruler of the historic Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia, and that the southern abutments and pier of the bridge have been built on the site of the Saxon burh that had been erected by her in 915.