Ecgbert

Ecgberht (771/775 – 839), also spelled Egbert, Ecgbert, or Ecgbriht, Ecgbeorht, was King of Wessex from 802 until his death in 839. His father was reputedly Ealhmund of Kent. In the 780s Ecgberht was forced into exile to Charlemagne's court in the Frankish Empire by Offa of Mercia and Beorhtric of Wessex, but on Beorhtric's death in 802 Ecgberht returned and took the throne of Wessex. In Chester, Ecgbert is commemorated by a bas-relief in the porch of the Town Hall with the somewhat enigmatic label "KING EGBERT UNITING THE KINGDOMS MERCIA" and a lot of foot-kissing by what are presumably the then local administration in Chester - although they may be meant to be conquered kings as they appear to be piling crowns at his feet, one of which feet conspicuously rests on a footstool.

Ecgbert was the king of Wessex who, during his long and eventful life, saw Mercia reach its zenith and begin its decline, while the fortunes of Wessex were to improve. At the time that the bas-relief at the Town Hall was created it was believed that Ecgbert was the first king of all England. If he was, he was so only briefly. Ecgbert would however have a major effect on Chester's future, but not in a way that is apparent from the sculpture.

Offa's Mercia

For 200 years (between 626 and 825), having annexed or gained submissions from five of the other six kingdoms of the Heptarchy (East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Sussex and Wessex), Mercia dominated England south of the River Humber: this period is known as the Mercian Supremacy. The reign of King Offa (757-796), who is best remembered for his Dyke that designated the boundary between Mercia and the Welsh kingdoms, is sometimes known as the "Golden Age of Mercia". However, historians differ on whether building of the eponymous dyke was actually started by Offa and some have suggested that work on the dyke started much earlier.

In the early years of Offa's reign, it is likely that he consolidated his control of Midland peoples such as the Hwicce and the Magonsæte. Taking advantage of instability in the kingdom of Kent to establish himself as overlord, Offa also controlled the kingdom of Sussex by 771, though his authority did not remain unchallenged in either territory. In the 780s he extended Mercian Supremacy over most of southern England, allying with Beorhtric of Wessex, who married Offa's daughter Eadburh, and regained complete control of the southeast. He also became the overlord of East Anglia and had King Æthelberht II of East Anglia beheaded in 794, perhaps for rebelling against him. He was not the ruler of all England as his dominance never extended to Northumbria, though Offa gave his daughter Ælfflæd in marriage to the Northumbrian king Æthelred I in 792. Northumbria was soon to collapse into a renewal of the civil war that had been on and off for some years. A group of nobles conspired to assassinate Æthelred in April 796 and he was succeeded by Osbald: Osbald's reign lasted only twenty-seven days before he was deposed and Eardwulf became king on 14 May 796. This record of disputed succession was by no means unique to Northumbria, and the kingdoms of Mercia and Wessex experienced similar troubles during the eighth and ninth centuries. In Wessex, from the death of Centwine in 685 to Egbert's seizure of power in 802, the relationships between successive kings are far from clear and few kings are known to have been close kinsmen of their predecessors or successors. The same may be true of Mercia from the death of Ceolred in 716 until the disappearance of the Mercian kingdom in the late ninth century.

Offa died in July 796. His son Ecgfrith succeeded him but reigned for less than five months before Coenwulf came to the throne. In the last few years of Offa's rule the first recorded Viking raids on Britain started. The first being in 789, with the noted Lindisfarne raid being in 793. The Vikings would be a signoficant influence on the next three-hundred years of British history, including that of Chester.

A key source for the period is the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a collection of annals in Old English narrating the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The Chronicle was a West Saxon production, however, and is sometimes thought to be biased in favour of Wessex; hence it may not accurately convey the extent of power achieved by Offa, a Mercian. Both the Chronicle and Victorian historians would puff-up the role played by Wessex, especially when Wessex had victories, although both would downplay the defeats which Wessex suffered.

Ecgbert

Historians do not agree on Ecgbert's ancestry and the date of his birth can only be estimated at around 771 to 775. The earliest version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the Parker Chronicle, begins with a genealogical preface tracing the ancestry of Ecgbert's son Æthelwulf (Alfred "the Great"'s father) back through Ecgbert, Ealhmund (thought to be Ealhmund of Kent), and the otherwise unknown Eoppa and Eafa to Ingild, brother of King Ine of Wessex, who abdicated the throne in 726. It continues back to Cerdic, founder of the House of Wessex. Ecgbert's descent from Ingild is accepted by historians, but not the earlier genealogy back to Cerdic. Some have argued that he was of Kentish origin, and that the West Saxon descent may have been manufactured during his reign, or possibly a little later, to give him legitimacy as an important founder of the ruling house of Wessex. Indeed Bishop Asser starts his Vita Ælfredi regis Angul Saxonum ("Life of King Alfred") with a genealogy of Alfred, tracing his line back to the rulers of Wessex with no mention of the fact that his father was king of Kent.

Cynewulf's murder

Like many of the early Anglo-Saxon kingdoms Wessex had frequent contested successions. Cynewulf became king of Wessex in 757 after his predecessor, Sigeberht, was deposed. He may have come to power under the influence of Æthelbald of Mercia, since he was recorded as a witness to a charter of Æthelbald shortly thereafter. However, it was not long before Æthelbald was assassinated (also in 757) and as a consequence, Mercia fell into a brief period of disorder as rival claimants to its throne fought. Cynewulf took the opportunity to assert the independence of Wessex: in about 758 he took Berkshire from the Mercians. In 779, Cynewulf was defeated by the new King of Mercia, Offa, at the Battle of Bensington, and Offa then retook Berkshire, and perhaps also London. The relationship between Offa and Cynewulf is not well documented, but it seems likely that Cynewulf maintained some independence from Mercian overlordship and there is no evidence to suggest Cynewulf subsequently became subject to Offa. In 786, Cynewulf was the victim of a surprise attack at his mistress's house in Merton by Cyneheard, brother of the deposed Sigeberht. Cynewulf was killed and Cyneheard was either killed or died very shortly after.

The succession to the now vacant throne of Wessex was contested by or on behalf of the young Ecgbert, but he was defeated by Beorhtric, maybe with Offa's assistance. The precise details are not clear, by some accounts hold that Egbert was forced to take refuge at the court of the powerful Offa and that Beorhtric responded by proposing an alliance between himself and Offa, which was to be cemented by his marriage to Offa's daughter Eadburh. He further requested that Offa deliver the "rebel" Ecgbert to him. Offa accepted Beorthric's offer for his daughter's hand in marriage, but instead of handing over Egbert to his enemy and certain death, he merely banished him from England. Other versions are quite different, based on the fact that around 790 there was a dispute between Offa and Charlemagne such that each ruler refused landfall to the ships and merchants of the other. Some have therefore suggested that Ecgbert could already be seen by Offa as a potential threat and that Offa would have preferred to have his killed. Offa is noted for killing-off even the most improbable potential rival and the history is much clouded by the fact that later chronicle-writers frequently had a bias towards Wessex.

One legend has it that Ecgbert was acually annointed as king at "Ecgbert's Stone" (Ecgbryhtesstan) prior to his exile. The stone's location is not known with any certainty and there are several other legends surrounding it: one that it was placed there by Ecgbert to settle to boundaries of Dorset, Wiltshire and Somerset. In the light of subsequent events the story of the annointing at the stone may be just a myth. In the Town Hall sculpture at Chester, Ecgbert seems to be collecting a pile of crowns at his feet placed there by those kneeling before him. This piling up of regalia is not appropriate symbolism as the first actual "coronation" was not until 925 when Æthelstan (another claimed as the first king of all England) was crowned and anointed. Prior to this it was the anointing (usually with myrrh) which was the important part of the ceremony and kings in England would probably have worn a helmet rather than a crown. Ecgbert being anointed at his "kings-stone" finds another echo in the "coronation" of Æthelstan, which was a stage-managed affair at Kingston upon Thames, but once again any connection between the two events is much clouded by myth and legend.

Beorhtric's murder

Egbert was forced to flee to a Francia, then ruled by Charlemagne and is said to have served in his army. He remained safely in France for the rest of Beorhtric's reign in Wessex, probably for thirteen years. Charlemagne's court at Aachen ended the Germanic custom of an itinerant court moving from place to place and established a real capital and was being built at the time that Ecgbert was in Francia. The arrival of the court in Aachen and the construction work stimulated the activity in the city that experienced growth in the late 8th century and the early 9th century, as craftsmen, traders and shopkeepers had settled near the court. It would have made a significant impression on Ecgbert. By 800, when he was crowned emperor, Charlemagne had conquered a realm spanning present-day France, Switzerland, Belgium, the Netherlands, large parts of Italy and Germany, and a good chunk of Austria and Spain. The continental power of the Carolingians was conveniently isolated from Britain by the English Channel, but this did not stop their influence reaching England and would affect the succession in several English kingdoms.

Meanwhile, according to Asser's history, Beorhtric's new wife Eadburh became all powerful, and often demanded the executions or exile of her enemies, whether real or supposed. She was also alleged to have assassinated those men whom she couldn't compel Beorhtric to kill, through poisoning their food or drink. Beorhtric's dependency on Mercia continued into the reign of Cenwulf, who became king of Mercia a few months after Offa's death. In 802, according to Asser, Eadburh attempted to poison a young favourite of the king but instead killed both of them. Eadburg subsequently fled to Francia and took refuge at the court of Charlemagne. There Asser relates that Charlemagne was smitten by the former queen. He brought in one of his sons and asked her which she preferred, him or his son, as a husband. She answered that, given the son's youth, she preferred the son. Charlemagne replied famously:

- "Had you chosen me, you would have had both of us. But, since you chose him, you shall have neither."

He instead offered her a position as an abbess of a convent which she accepted. Soon though she was caught in a sexual affair with another Saxon man and, after being duly convicted, was expelled on the direct orders of Charlemagne, penniless, into the streets. In her last years (according to the later chronicles) she lived as a beggar on the streets of Pavia. It is possible that much of the blackening of her name by later writers may have been to discredit Beorhtric's line. Charlemagne even considering marriage really does not make sense given that her father and brother were dead, leaving her without the family connections needed to form alliances. In reality, she may have ended her days in Lombardy, but not reduced to begging on the streets, as there are records if an "Eadburh" being the abbess of a large convent.

Ecgbert becomes king

When Beorhtric died in 802, and Eadburh arrived at Charlemagne's court with her tale of the unfortunate catering mishap, Ecgbert's fortunes changed. Ecgberht soon came to the throne of Wessex, probably with the support of Charlemagne and perhaps also the papacy (Leo III, who was much influenced by Charlemagne). Such is the Wessex version, although some might suspect that another was actually the owner of the hand behind the poison and Eadburh the convenient scape-goat.

The Mercians (ruled, according to some, by the future Saint Kenelm) opposed Ecgberht's succession. Even on the day of the "coronation" Wessex was attacked by the Hwicce, under ealdorman Æthelmund (the Hwicce had originally formed a separate tribal kingdom, but by that time formed part of Mercia). Weohstan, a Wessex ealdorman and said by one source to be Egbert's brother-in-law, met the Mercians with men from Wiltshire. The Hwicce were defeated in the Battle of Kempsford, and Weohstan and Æthelmund both slain. Attacks on another kingdom at or around the time of a change of rulership were a farly frequent feature of this period of Anglo-Saxon history and several reasons can be considered for these including the expiry of what were effectively personal treaties between rulers, a potential weakness of leadership in times of transition or simply the fact that the Anglo-Saxons attacked each other so often that someone might be having a "coronation" simply by chance. As will be seen, the Vikings were particularly prone to try their chances at times of regimen change. In the case of Ecgberht's succession and the attempts by Mercia to intervene the history is horribly muddled, with the challenge coming not from the ruler of Mercia (according to some accounts the legendary Saint Kenelm) but from the Hwicce. All this vagueness about who was involved and who was in charge possibly points to later revisions of history by chonicle writers with a particular axe to grind, or blunt. Just how the exile Ecgbert returned to become the ruler of Wessex is something that might never be clarified.

Whatever myths were created Ecgbert soon had a real problem. In 807 the Vikings landed on the Cornish coast, and formed an alliance with the Cornish to fight against Wessex. Cornwall and Wessex had been engaged in conflict since the sixth century. In 577, the Battle of Deorham Down near Bristol resulted in the separation of the Cornish (known as the West Welsh) from the Welsh by the advance of the Saxons. At this point some historians believe that the Cornish and Welsh languages began to separate. Egbert conquered Cornwall in 814 but was unsuccessful in subjugating the people despite having laid waste the land. The Cornish eventually rose against Egbert only to be defeated in 825 at Gafulford, whose location is not known with certainty but is probably on the Cornwall/Devon border: of the several locations that have been proposed, Camelford in Cornwall and Galford near Lew Trenchard in West Devon have had the widest acceptance. In 838 a Cornish-Danish alliance was initially successful in a number of skirmishes with Egbert, but was eventually defeated in a pitched battle at Hingston Down, near Callington. This was the last battle against the Saxons in this particular comflict, by which time the Cornish/Norwegian Viking alliance seems to have lasted for a surprising thirty years.

Apart for his battles in Cornwall, little is known of the first 20 years of Ecgberht's reign, but it is thought that he was able to maintain the independence of Wessex against the kingdom of Mercia, which at that time still dominated the other southern English kingdoms. Then, in 825 Ecgbert defeated Beornwulf of Mercia, ended Mercia's supremacy at the Battle of Ellandun, and proceeded to take control of the Mercian dependencies in southeastern England. It appears that Beornwulf was the aggressor in this case and his attack on Wessex may have been part of an effort to consolidate his own somewhat shaky and recently gained authority. Beornwulf may also have been seeking to take advantage of Ecgbert's preoccupation with warfare against the Britons of Cornwall and their Viking allies. Ecgberht had devastated Cornish territory in 815 and in the autumn of 825 he was again campaigning against the Britons, at Gafulford.

Richard of Devizes in the late 12th Century Annales de Wintonia (Winchester Chronicles) describe Beornwulf as:

- "deriding the ability of King Egbert" .. "keen to play him at the game of war" .. "He invited and provoked the latter's army to battle in order to make him pay homage. Egbert consulted his noblemen and the choice was made to drive off shame with the sword. It was more honourable to be slain than to submit their freedom to the yoke"

While numbers appear exaggerated it is generally accepted that Ecgbert was greatly outnumbered. However, his army was possibly better trained given the recent fighting against Cornwall. Henry of Huntingdon described a local stream as running "red with gore." Writing 300 years after the event he said the water was "choked with the slain and became foul with carnage."

Ecgbert's victory transformed the political situation in south-eastern England. The king at once sent his son Æthelwulf with an army into the south-east. The West Saxons succeeded in conquering Sussex (hitherto under direct Mercian rule), Kent, and Essex, which had been governed by sub-kings under Mercian overlordship. All of these territories were annexed to Wessex, roughly doubling the kingdom's size. Meanwhile, Beornwulf's defeat emboldened the East Angles to revolt against Mercian rule and reassert their independence, in alliance with Wessex. Beornwulf then fought the East Angles, but was defeated and killed. His successor Ludeca met the same fate the following year. Such were the often chaotic shifts in fortunes and alliances in Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of that time.

Mercia falls

Worse was to come for Mercia. In 829 Ecgbert defeated Wiglaf of Mercia and drove him out of his kingdom, temporarily ruling Mercia directly. It is not clear who started that particular conflict. Later that year Ecgberht received the submission of the Northumbrian king Eanred at Dore. Dore is on or very near what would have been the border of Mercia with Northumbria and there is nothing to suggest that Ecgbert had to take his army into Northumbria or fight any battle. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle subsequently described Ecgberht as a bretwalda or "wide-ruler" of Anglo-Saxon lands. A West Saxon scribe described him as a "bretwalda", meaning "wide-ruler" or "Britain-ruler", in a famous passage in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. The relevant part of the annal reads, in the [C] manuscript of the Chronicle:

- "This year was the moon eclipsed, on mid-winter's mass-night; and King Egbert, in the course of the same year, conquered the Mercian kingdom, and all that is south of the Humber, being the eighth king who was sovereign of all the British dominions. Ella, king of the South-Saxons, was the first who possessed so large a territory; the second was Ceawlin, king of the West-Saxons: the third was Ethelbert, King of Kent; the fourth was Redwald, king of the East-Angles; the fifth was Edwin, king of the Northumbrians; the sixth was Oswald, who succeeded him; the seventh was Oswy, the brother of Oswald; the eighth was Egbert, king of the West-Saxons. This same Egbert led an army against the Northumbrians as far as Dore, where they met him, and offered terms of obedience and subjection, on the acceptance of which they returned home."

This may be unashamed Wessex propaganda, with Ecgbert being added to a list provided by Bede and compared to a clutch of famous rulers who were each supposedly "bretwalda" for a number of years. The list is interesting in that it begins with some early pagan founders but then has a group of rulers with overlapping lives in the 6th/7th centuries each of whom were involved in the early development of the church. It also omits Penda, the Mercian King who defeated Edwin of Northumbria before himseld being defeated by Oswald:

- Ælle of Sussex (c 477-514): recorded in early sources as the first king of the South Saxons, he may have only ruled Sussex;

- Ceawlin of Wessex (died c593): recorded as the leader of the first group of Saxons to come to the land which later became Wessex;

- Æthelberht of Kent (c550-616): the first English king to convert to Christianity. He was King of Kent but may have exercised some wider influence;

- Rædwald of East Anglia (c599-624): again, another convert;

- Edwin of Northumbria (c586-633): yet another convert - later venerated as a saint;

- Oswald of Northumbria (c604-642): did much to spread the christian religion in Northumbria

- Oswiu of Northumbria (c612-670): notable for his role at the Synod of Whitby in 664, which ultimately brought the church in Northumbria into conformity with the wider Catholic Church;

The Wessex-based compilers of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle take Bede's list, which essentially shows how great the Northumbrians are, especially when it comes to helping the spread of Bede's favoured form of christianity and add Ecgbert after a gap of almost two centuries. The Wessex chroniclers do not hesitate to take the opportunity to imply that Ecgbert was even more powerful than the Northumbrians. They overlook that Ecgbert had little if anything to do with the development of religion. The Victorians seemed to favour the view that "bretwalda" was some kind of political title - an idea they found attractive because it would lay the foundations for the establishment of an English monarchy, especially one which fitted into the "Anglo-Saxonist" view of history prevalent at the time. By other accounts, Ecgbert seems to have plundered every territory he "conquered" - to quote Roger of Wendover:

- "When Egbert had obtained all the southern kingdoms, he led a large army into Northumbria, and laid waste that province with severe pillaging, and made King Eanred pay tribute"

..but as noted above the Anglo Saxon Chronicle simply has a meeting on the border after which the parties went home. Ecgbert's position as the one who "united the kingdoms" as expressed at the Town Hall in Chester is probably more down to Wessex propaganda and the Victorian view of history than actual historical establishment of any kind of real unity. Ecgbert didn't even keep Mercia for that long - in 830, Mercia regained its independence under Wiglaf — the Chronicle merely says that Wiglaf "obtained the kingdom of Mercia again".

Ecgbert and Chester

Samuel Lewis (in his Topographical Dictionary of Wales) does not paint Egbert in a good light:

- "Immediately after surrender of Chester to Egbert of Wessex, the whole of the present county of Flint, being an open tract devoid of those rugged and almost inaccessible elevations which occupy so much of the rest of North Wales, became subject to the arms of that powerful monarch who carried his devastations to the foot of the mountains."

Egbert appears to have visited Chester but once, around 830. As one writer records:

- During Egbert’s final war with Cornwall, the North Welsh had to the best of their ability aided their fellow Britons, and therefore Egbert launched a punitive expedition against them. He laid siege to and took Chester, then capital of the Welsh kingdom of Gwynedd – strongest of all the several North Welsh states. Of the punishments Egbert visited upon these Britons, the most humiliating was his command that the statue of their ancient king, Cadwalhon, be destroyed and never replaced. When he returned to Wessex, Egbert decreed that all the Welsh and their offspring leave his kingdom within six months or be put to death. Egbert ordered this apparently at the instigation of his wife, Redburga, who did exercise some political influence over her husband, and whose hatred of the Welsh was well-known.

Historians now consider that Ecgbert's wife was not Redburga, who first turns up in a 15th century chronicle and the reference to her is seen as a late addition. Similarly the stories that she was a relative of Charlemagne are also dismissed. An alternative explanation is that Gwynedd was supprting the Cornish and that the attack on Chester by Ecgbert was a punitive expedition. The politics of Gwynedd at the time are complicated with the House of Cunedda expiring in the male line in 825 upon the death of the ruler known as Hywel ap Rhodri Molwynog. Merfyn Frych was King of Gwynedd from around 825 to 844 and so would have been the ruler of Chester in 830 if Lewis is correct to say that it was the capital of Gwynedd. However coastal Wales along the Dee Estuary must have been under Mercia’s control through 821, as Coenwulf is recorded dying peacefully at Basingwerk in that year.

Both Holinshead and Fox repeat the story that Chester was part of Wales. Holinshead recounts the conquest as follows:

- After that king Egbert had finished his businesse in Northumberland, he turned his power towards the countrie of Northwales, and subdued the same, with the citie of Chester, which till those daies, the Britains or Welshmen had kept in their possession. When king Egbert had obteined these victories, and made such conquests as before is mentioned, of the people héere in this land, he caused a councell to be assembled at Winchester, and there by aduise of the high estates, he was crowned king, as souereigne gouernour and supreame lord of the whole land.

Foxe puts it:

- Bernulph, king of Mercia above mentioned, with other kings, had this Egbert in such derision, that they made of him divers scoffing jests and scorning rhymes, all which he sustained for a time. But when be was more established in his kingdom, and had proved the minds of his subjects, and especially God working withal, he afterward assembled his knights, and gave to the said Bernulph a battle in a place called Elinden, in the province of Hampton; and notwithstanding in that fight was great odds of number, as six or eight against one, yet Egbert (through the might of the Lord, which giveth victory as pleaseth him) had the better, and won the field; which done, he seized that lordship into his hand; and that also done, he made war upon the Kentish Saxons, and at length of them in like wise obtained the victory. And, as it is in Polychronicon testified, he also subdued Northumberland, and caused the kings of these three kingdoms to live under him as tributaries, or joined them to his kingdom. This Egbert also won from the Britons, or Welchmen, the town of Chester, which they had kept possession of till this day.

As will be noted some of these records are utterly unclear. In one version Chester is the capital of Gwynedd, in another the Mercians seem but a few years before to hold land as far as Offa's Dyke in 821 and have penetrated as far as Deganwy in 823, which they burned down. If all versions are believed Chester must have been changing hands rapidly at this time. According to a possibly dubious source, in 839 Egbert's successor, Æthelwulf of Wessex, held the Witenagemot (literally "meeting of the wise") in Chester, and, being crowned (in Kingston not Chester?), received at Chester the homage of tributary kings, "From Berwick to Kent." (Encyl Brit 1911 - not found in the A.S. Chron - and Wiglaf should have been in charge then). Whether some of this confusion arises from Wessex propaganda or simply from poor records is not known for certain, although when Asser (Alfred's Welsh bishop) was writing his "Life of King Alfred" in 893 he omits much of the history of the conflict between Wessex and Mercia, even though it would have been still at the limits of living memory.

Later Reign and Succession

Ecgbert's dominion of England came to an end with Wiglaf's recovery of power. Wiglaf's return is followed by evidence of his independence from Wessex. Historians have sought reasons why Ecgbert's rulership of Britain was so brief. It could be that he was fortunate as regards being able to exploit political instability in the other kingdoms of Britain. It is possible that he had for a while strong support from the Carolingians which faded away when the power of Louis the Pious was weakened by civil war after about 830. It is also possible that the alliance between the Cornish and the Vikings was a long drain on his resources. he was defeated by the Danes in 836 and it took him until 838 to finally defeat the alliance. Another view is that Ecgbert never really had "overlordship" but simply conducted a series of raids against enemies who were suffering from temporary weakness and would have been quite unable to hold all the teritory that he supposedly "united". Another possibility is that Wiglaf returned as a vassal king under the overlordship of Ecgbert. This could have been a practical solution if there was trouble on the Mercian/Welsh border.

The extent of Ecgbert's involvement with the church is unknown. At a council at Kingston upon Thames in 838, Ecgberht and his son Æthelwulf granted land to the sees of Winchester and Canterbury in return for the promise of support for Æthelwulf's claim to the throne. At Canterbury in 828 Egbert granted privileges to the bishopric of Rochester, and Egbert and Æthelwulf appear to have taken steps to secure the support of Archbishop Wulfred, but this was a mutually beneficial arrangement: Ecgbert wanted to ensure support for his son and the church at Canterbury was now looking to Ecgbert to provide protection against the Vikings given the decline of Mercian power. When Wessex had first gained control of Kent from Mercia relations had been farly cold, and the lucrative right for the archbishop to issue his own coins had been suspended for a time. The church at Canterbury was also keen to get it's "foot in the door" with Ecgbert, who may have imported scribes to prepare charters from the Carolingians rather than use the services of the local church. Later chronicles say a great deal about Æthelwulf's generousity to the church, both during his life and in his will and refer to many charters granting rights to the church (some of which may have been forgeries). However they say very little about grants from Ecgbert.

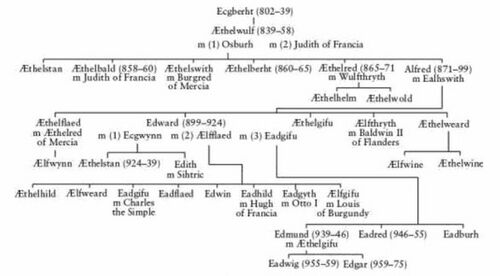

Ecgbert's son Æthelwulf and his first wife, Osburh, had five sons and a daughter. Viking raids increased in the early 840s on both sides of the English Channel, and in 843 Æthelwulf was defeated by the companies of 35 Danish ships at Carhampton in Somerset. In 850 sub-king Æthelstan and Ealdorman Ealhhere of Kent won a naval victory over a large Viking fleet off Sandwich in Kent, capturing nine ships and driving off the rest. The following year the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records five different attacks on southern England. A Danish fleet of 350 Viking ships took London and Canterbury, and when King Berhtwulf of Mercia went to their relief he was defeated. The Vikings then moved on to Surrey, where they were defeated by Æthelwulf and his son Æthelbald at the Battle of Aclea. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle the West Saxon levies "there made the greatest slaughter of a heathen that we have heard tell of up to the present day". In 850 a Danish army wintered on Thanet, and in 853 ealdormen Ealhhere of Kent and Huda of Surrey were killed in a battle against the Vikings, also on Thanet. In 855 Danish Vikings stayed over the winter on Sheppey, before carrying on their pillaging of eastern England. Æthelwulf set out for Rome in the spring of 855, accompanied by his youngest son Alfred and a large retinue. In view of the ongoing Viking raids it seeems a surprising thing to do, and has led to much debate as to Æthelwulf's competence as a leader. The King left Wessex in the care of his oldest surviving son, Æthelbald, and the sub-kingdom of Kent to the rule of Æthelberht, and thereby confirmed that they were to succeed to the two kingdoms. Æthelwulf returned to Wessex from his trip to Rome to face a revolt by Æthelbald, who attempted to prevent his father from recovering his throne. Æthelwulf agreed to give up the western part of his kingdom - Wessex itself - in order to avoid a civil war and retained Kent, Essex and Sussex for himself.

Æthelwulf survived his unhappy homecoming for two years and died on 13 January 858. According to the Annals of St Neots, he was buried at Steyning in Sussex, but his body was later transferred to Winchester, probably by Alfred. Following the Norman conquest, Winchester Cathedral was erected on the Saxon site of the Old Minster. The Royal remains, including King Egbert's bones and those of Æthelwulf, were exhumed and placed around St. Swithin's Shrine in the new building. However in the seventeenth century, during the English Civil War, the bones, after being used by Cromwell's soldiers as missiles to shatter stained glass windows, were scattered and mixed in various mortuary chests along with those of other Saxon kings and bishops and the Norman King William Rufus. The chests remain today, seated upon a decorative screen surrounding the presbytery of the Cathedral.

As Æthelwulf had intended, he was succeeded by Æthelbald in Wessex and Æthelberht in Kent and the south-east. The prestige conferred by a Frankish marriage was so great that Æthelbald then wedded his step-mother Judith, to Asser's retrospective horror; he described the marriage as a "great disgrace", and "against God's prohibition and Christian dignity". When Æthelbald died (childless) only two years later, Æthelberht became King of Wessex as well as Kent, and Æthelwulf's intention of dividing his kingdoms between his sons was thus set aside. Æthelberht did not appoint a sub-king and Wessex and Kent were fully united for the first time. Æthelberht's reign began and ended with raids by the Vikings. In 860 a Viking army sailed from the Somme to England and sacked Winchester, but they were then defeated by the men of Hampshire and Berkshire. Probably in the autumn of 864, another Viking army camped on Thanet and were promised money in return for peace, but they broke their promise and ravaged eastern Kent. Æthelberht died of unknown causes in the autumn of 865.

The throne now passed to the fourth son of Æthelwulf, and the third to succeed him as king. Æthelred's accession (865) coincided with the arrival of the Viking "Great Heathen Army" in England. This was less of a raid and more of a definite attempt at permanent conquest and settlement. The reasons why the Vikings should change their tactics can only be speculated upon: there may have been population pressure building in Scandinavia for some years, or, ther may have been a fall-off in agricultural production or fishery harvests due to climate change. It was certainly at times a cold period: on 859 the weather was so severe that the Adriatic Sea froze, and Italy was covered in snow for 100 days. Over the next five years the Vikings conquered Northumbria and East Anglia, and at the end of 870 they launched a full-scale attack on Wessex. In early January 871 Æthelred was defeated at the Battle of Reading. Four days later he scored a victory in the Battle of Ashdown, but this was followed by two defeats at the Battle of Basing (late January 871) and battle of Meretun (March 871). He died shortly after Easter 871, possibly of battle injuries. Æthelwulf's only remaining son was Alfred, his fifth, and almost certainly originally destined for the church.

Both Ecgbert's stone and Chester would also play a part in Alfred's life.

Summarising Ecgbert

What is known of Ecgbert from historians can be read in several ways and his true story seems to have been buried under layers of legend. The process continues in modern literature, where, in the Canadian-Irish television series "Vikings" a fictional "Egbert" appears and commits suicide, something for which there is no historic evidence whatsoever. The later Wessex chronicle-writers sought to portray Ecgbert as a heroic figure who was a rightful king, wrongly exiled and swearing an oath to return at Ecgbert's Stone, who did indeed return from the prestigious court of Charlemagne and became the overlord of the whole land. There is certainly a core of truth in this account of him, but much of the detail appears to have been presented in such a manner as to support the position that Alfred's Wessex was the logical inheritor of the English crown.

Alfred and the Vikings

Æthelred left two under-age sons at his death, Æthelhelm and Æthelwold, but Alfred and his brother had agreed that whichever of them outlived the other would inherit the personal property that King Æthelwulf had left jointly to his sons in his will. The deceased's sons would receive only whatever property and riches their father had settled upon them and whatever additional lands their uncle had acquired. The unstated premise was that the surviving brother would be king. Given the Danish invasion and the youth of his nephews, Alfred's accession probably went uncontested. While he was busy with the burial ceremonies for his brother, the Danes defeated the Saxon army in his absence at an unnamed spot and then again in his presence at Wilton in May. The defeat at Wilton smashed any remaining hope that Alfred could drive the invaders from his kingdom. Alfred was forced instead to make peace with them, probably in return for a large monetary payment. For the next four to five years the Danes spent their time in other parts of England and left Wessex alone. Paying the Vikings to go away was not exactly a cowardly act as Burgred of Mercia (Alfred's brother in law) had done the same in 869, 871, and 872.

During this period of peace we know very little of what Alfred did, other than that he started to form a navy. Meanwhile the Vikings dismembered Mercia. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle offers the following account of what happened in 874:

- "This year went the army [i.e., the Great Heathen Army] from the Kingdom of Lindsey to Repton, and there took up their winter-quarters, drove the king [of Mercia], Burgred, over sea, when he had reigned about two and twenty winters, and subdued all that land. He then went to Rome, and there remained to the end of his life. And his body lies in the church of Sancta Maria, in the school of the English nation. And the same year they gave Ceolwulf, an unwise king's thane, the Mercian kingdom to hold..."

It was at this time that a much later tradition states that the remains of St Werburgh were relocated to Chester. As recorded in the Annales Cestriensis:

- In the same year, when the Danes made their winter quarters at Repton after the flight of Burgred, king of the Mercians, the men of Hanbury, fearing for themselves, fled to Chester as to a place which was very safe from the butchery of the barbarians, taking with them in a litter the body of S Werburgh, which then for the first time was resolved into dust.

The men of Hanbury may not only have feared the violence of the Vikings at Repton but may also have been concerned about the fact that the Vikings were dropping like flies from what may well have been a plague in their winter quarters.

It would by 875 before the Vikings would be a significant problem for Wessex again. By that time the Great Heathen Army had been in Britain for ten years and yet there had been no real attempt to unite what remained of the Heptarchy against them.

The "Conquest" of Mercia

Up until 2015 historians generally believed the Wessex chronicler version that Coelwulf II was "an unwise king's thane" who was appointed as king of Mercia as the puppet of the Vikings. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle writes of Ceolwulf:

- "...He swore them oaths and gave hostages, so that it would be ready for them on whatever day they would have it, and he himself ready, and all those who would follow him at the force's need."

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is however, known to be biased in favour of Wessex. It is considered to be politically motivated, written with a view of strengthening the claims of Alfred and his son Edward the Elder to the overlordship of Mercia, and playing down any contribution by the Mercians. This is seen particularly clearly in terms of the deeds of Æthelflæd who was almost entirely written out of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. That Coelwulf was rather more than a "foolish thane" is evidenced by a 2015 find of Anglo-Saxon "Imperial" coins dated to around 879 CE, known as the Watlington Hoard presumed to have been buried by retreating Vikings. Most of the coins show an emperor’s head on one side and two royal figures seated side by side on the other. The coins are believed to depict both Ceolwulf as a king as well as Alfred on the same coins, leading some experts to conclude that the two were being portrayed as equals. Only a single instance of this coin had been found before. Other coinage of Coelwulf and Alfred also show similarities, and this has been taken as further evidence that they may have co-operated against the Vikings. The newly found coins cover several years and were struck in different mints, demolishing the earlier belief that the two kings issued "joint" coins in only one year, marking a very short-lived alliance and a one-off issue. It was announced in February 2017 that the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford had purchased the hoard for £1.35m, to keep it within the county, with funding from the National Lottery, the Art Fund and local donations.

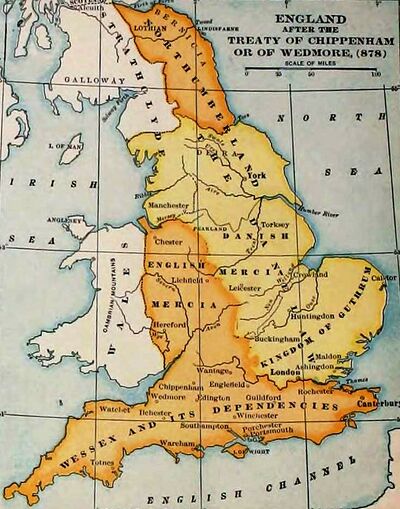

It seems likely that Ceolwulf II was a direct descendent of Ceolwulf I and Coenwulf, of the rival 'C' dynasty, beginning with Coenwulf, which may have had ties to the ruling family of Hwicce in south-west Mercia. It is also a possibility that those Mercians who supported him had promoted him, at Burgred's defection, rather than suffer a king appointed by the Vikings. Another possibility is that the Mercians themselves toppled Burgred, with whom they had become disaffected, in order to promote his political rival, Ceolwulf; the Vikings being a mere catalyst to events. One scenario is that Ceolwulf's kingdom was reduced to the northern and western parts of Mercia (which would possibly include Chester). In 878, King Rhodri Mawr of Gwynedd was killed in battle against the English. As Alfred was then occupied fighting the Vikings, and Mercia traditionally claimed hegemony over Wales, the English leader was probably Ceolwulf (see below), who was fated to be written out of history.

The Return of the King

In 876, under their three leaders Guthrum, Oscetel and Anwend, the Danes slipped past the Saxon army and attacked and occupied Wareham in Dorset. Alfred blockaded them but was unable to take Wareham by assault. He negotiated a peace that involved an exchange of hostages and oaths. The Danes broke their word, and after killing all the hostages, slipped away under cover of night to Exeter in Devon. Alfred blockaded the Viking ships in Devon, and with a relief fleet having been scattered by a storm, the Danes were forced to submit. The Danes withdrew to Mercia. On Epiphany, 6 January 878, Guthrum made a surprise night-time attack on Alfred and his court at Chippenham, a royal stronghold in which Alfred had been staying over Christmas:

- "and most of the people they killed, except the King Alfred, and he with a little band made his way by wood and swamp, and after Easter he made a fort at Athelney in the marshes of Somerset, and from that fort kept fighting against the foe"

Alfred spent the winter as a fugitive, and from this period comes the famous story of the "burning of the cakes". A legend tells how when Alfred first fled to the Somerset Levels, he was given shelter by a peasant woman who, unaware of his identity, left him to watch some wheaten cakes she had left cooking on the fire. Preoccupied with the problems of his kingdom, Alfred accidentally let the cakes burn and was roundly scolded by the woman upon her return. There is no contemporary evidence for the legend, but it is possible that there was an early oral tradition. The first time that it was actually written was about 100 years after Alfred's death. The Victorians turned this into a metaphor of the almost completely beaten ruler driven into a desparate position which only gets worse in a mildly amusing way. Alfred's emergence from his marshland retreat was part of a carefully planned offensive that entailed raising the fyrds of three shires. This meant not only that the king had retained the loyalty of ealdormen, royal reeves and king's thegns, who were charged with levying and leading these forces, but that they had maintained their positions of authority in these localities well enough to answer his summons to war.

Tradition holds that Alfred ordered that his troops should gather at Ecgbert's stone, the very same spot where his grandfather was reputed to have made an oath to return while heading for exile in Francia. It may be that this idea of the "covenant stone" developed later, and was influenced by the story in the Book of Joshua about the large "massebah" or standing stone in front of the Shechem temple. A similar idea is used by Tolkein in the form of the "Stone of Erech", which is used as a rallying point by Aragorn in "Return of the King". According to the Life:

- "Fighting ferociously, forming a dense shield-wall against the whole army of the Pagans, and striving long and bravely...at last he [Alfred] gained the victory. He overthrew the Pagans with great slaughter, and smiting the fugitives, he pursued them as far as the fortress."

The Anglo Saxon Chronicle records the terms of the surrender:

- "Then the raiding army granted him [Alfred] hostages and great oaths that they would leave his kingdom and also promised him that their king [Guthrum] would receive baptism; and they fulfilled it. And three weeks later the king Guthrum came to him, one of thirty of the most honourable men who were in the raiding army, at Aller – and that is near Athelney – and the king received him at baptism; and his chrism loosing was at Wedmore."

The Victorians depicted the Battle of Edington as a great victory, wheras in fact it led to a stalemate. A significant part of the Viking forces were able to escape and find refuge, apparently in Alfred's own fortress at Chippenham, where they were besieged and starved into negotiation. Neither force was strong enough to gain a decisive result. In 875 Guthrum had lost the support of other Danish lords, including Ivar and Ubba. Further Danish forces had settled on the land before Guthrum attacked Wessex: in East Anglia, and in Mercia between the treaty at Exeter and the attack on Chippenham; many others were lost in a storm off Swanage in 876-7, with 120 ships wrecked. Internal disunity was threatening to tear the Danes apart, and they needed time to reorganize. Fortunately for Wessex, they did not use the time available effectively, wheras Alfred did.

Meanwhile, in the North

As noted above, at almost the same time as Alfred's victory over the Vikings in 878 at the Battle of Edington, Ceolwulf of Mercia defeated and killed Rhodri ap Merfyn (c. 820–878), later known as Rhodri the Great (Welsh: Rhodri Mawr), king of the north Welsh territory of Gwynedd. War with Wales, which typically involved fighting over and raiding each others border lands was a long-standing tradition for the Mercians. In 881 Rhodri's sons defeated the Mercians at the Battle of the Conwy, a victory described in Welsh annals as "revenge of God for Rhodri". The Mercian leader was, according to the Welsh histories, "Edryd Long-Hair", almost certainly Ceolwulf's successor as Mercian ruler, Æthelred. As for Ceolwulf's fate, history is silent. By 883 he had been definitely replaced by Æthelred but how this came about is not known - Ceolwulf simply disappears between his victory in 878 and the defeat of his successor in 881.

The Battle of the Conwy ended the traditional hegemony of Mercia over north Wales and probably contributed to Æthelred's decision to accept the lordship of King Alfred of Wessex. This united under Alfred the Anglo-Saxons who were not living under Viking rule, and was a significant step towards the creation of the Kingdom of England. The alliance was cemented by the marriage of Æthelred to Alfred's daughter Æthelflæd. The Welsh victor Anarawd allied himself with the Vikings shortly after the battle, but he then abandoned this alliance to follow Æthelred in also accepting Alfred's lordship. Whether this was more due to the Viking threat or diplomacy on the part of Alfred is not known, but the kingdoms of England and Wales appear to have been united under Alfred against a common enemy rather than by the force of arms.

After his "victory" Alfred now took some decisive steps to consolidate his position. He instituted the "Burh" system. This consisted of the development of fortified settlements and a network of roads connecting them. Some were new constructions; others were situated at the site of Iron Age hillforts, promontory forts or Roman forts and often employed materials from the original fortifications. Burhs also had a secondary role as commercial and sometimes administrative centres. Their fortifications were used to protect England's various royal mints. Initially established in Wessex by Alfred, later Burhs were developed in Mercia by his son Edward the Elder, his daughter Ethelfaed and her husband. The Burhs were instrumental in not only defending against attack but enabling the regaining of lost territory. The Burhs ensured that all of King Alfred's subjects would be close to safety, typically not more than 20 miles (one day) away. The image of a united England where everyones fortified home-town was in effect his castle was taken up by Victorian historians with great enthusiasm. One thing that many of the Victorian historians neglect to mention is that at the time Francia was falling apart through civil strife and the Vikings found easier pickings in mainland Europe rather than in England.

In 886, Alfred took possession of London, which had suffered greatly from several Viking occupations; as it had traditionally been a Mercian town, he handed control to Æthelred. In 892 the Vikings renewed their attacks, and the following year Æthelred (by now Alfred's son in law) led an army of Mercians, West Saxons and Welsh to victory over a Viking army at the Battle of Buttington. Alfred was not present as he was fighting the Vikings near Exeter. Æthelred spent the next three years fighting the Vikings alongside Alfred's son, the future King Edward the Elder. As with the other activities of the Mercians the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle probably plays down the role of Æthelred in this part of the conflict against the Vikings.

"Alfred" and Chester

In 892 (or 893) a new wave of Danes again attacked Britain in force. Finding their position in mainland Europe (on the French coast) precarious as a previously civil war torn Francia began to get its act together, this new horde crossed to England in 330 ships in two divisions. They entrenched themselves, the larger body, at Appledore, Kent and the lesser under Hastein, at Milton, also in Kent. The invaders brought their wives and children with them indicating a meaningful attempt at conquest and colonisation. One of their moves was a foray round the coast and the occupation of Exeter, something which must have been of much concern to Alfred given the trouble that his grandfather Ecgbert had with the Viking/Cornwall alliance. After some confused fighting a force of Vikings made a sudden dash across England and occupied Chester. The following account appears in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle:

- Þa hie on Eastseaxe comon to hiora geweorce. 7 to hiora scipum. þa gegaderade sio laf eft of Eastenglum, 7 of Norðhymbrum micelne here onforan winter 7 befæston hira wif, 7 hira scipu, 7 hira feoh on Eastenglum, 7 foron anstreces dæges 7 nihtes, þæt hie gedydon on anre westre ceastre on Wirhealum, seo is Legaceaster gehaten; Þa ne mehte seo fird hie na hindan offaran, ær hie wæron inne on þæm geweorce; Besæton þeah þæt geweorc utan sume twegen dagas, 7 genamon ceapes eall þæt þær buton wæs, 7 þa men ofslogon þe hie foran forridan mehton butan geweorce, 7 þæt corn eall forbærndon, 7 mid hira horsum fretton on ælcre efenehðe. 7 þæt wæs ymb twelf monað þæs þe hie ær hider ofer sæ comon. (As soon as they came into Essex to their fortress, and to their ships, then gathered the remnant again in East-Anglia and from the Northumbrians a great force before winter, and having committed their wives and their ships and their booty to the East-Angles, they marched on the stretch by day and night, till they arrived at a western city in Wirral that is called Chester. There the army could not overtake them ere they arrived within the ramparts: they besieged the ramparts though, without, some two days, took all the cattle that was thereabout, slew the men whom they could overtake outside the ramparts, and all the corn they either burned or consumed with their horses every evening. That was about a twelvemonth since they first came hither over sea.)

The Vikings possibly set up camp at the Amphitheatre, as later historians describe them as occupying the castle:

- The Danes, the following and more terrible invaders, who had been allowed by Alfred the Great to settle in Northumberland, next assailed Chester, and seized the fortress, which was circular and of red stone...

There are several things wrong with this quote, the Vikings in question were not from Northumbria, and Alfred never let them settle there, although the Vikings in Essex were re-inforced by a contingent from Northumbria. It also appears to be a propogation of the myth that Chester had a castle prior to the Normans. In later years stone from the round, red sandstone amphitheatre was robbed-out for use in the building of St Johns and it is possible that some of the re-used stone is marked with a runic inscription which the Vikings may have left behind. The reason why the Vikings made for Chester is unclear (see: Amphitheatre for a further discussion), but these Danish Vikings may have been trying to make contact with the Norwegian Vikings of Dublin. If that was the case the result could have been a desparate situation for Alfred, especially of the Vikings could establish a permanent base at Chester, occupying the Roman defences with a usable port as they had done at Exeter. If the military importance of Chester as an Irish Sea port had not been apparent to Alfred previously then it must have become so at that time. Just who led the forces opposing the Vikings is unclear and it may not have been Alfred himself. One possibility is that it was Æthelred or possibly even Æthelflæd. It could have been Æthelflæd's brother, the future king Edward the Elder (who was to die at Farndon after a later fight at an often disputed Chester) but the fact that the Wessex choniclers did not mention who was in charge, or even whether the Vikings were ousted by forces from Wessex or Mercia, suggests that it was Mercian forces who relieved Chester.

The Viking raid on Chester in around 893/4 may have had another consequence, as when the Vikings were driven off they spent some time ravaging Wales. At about this time Bishop Asser broke off writing his "Life of Alfred" - which was to remain incomplete. It may be that the "Life" was intended in part for a Welsh audience and that Asser stopped work on it after Alfred appeared to permit an attack on his native Wales.

In retrospect, Alfred (or possibly even Æthelflæd) would have been a far better choice for the bas-relief at the Town Hall rather than Ecgbert. The expulsion of the Vikings from Chester led to a significant change in the fortunes of the city, as it was once again recognised as an important strategic site and would be fortified as a burh by Alfred's daughter Æthelflæd.

Summary

In hindsight Ecgbert seems to have led a charmed life. He makes a failed attempt at the throne of Wessex and then spends well over ten years at the court of Charlemagne before a bungled poisoning leaves a vacant Wessex throne to which he returns. He fights an on-off war against a Cornish/Viking alliance with some defeats before his eventual victory as a very old man for the times. In the middle of this he is attacked by and defeats Mercia, attacks Wales and gains the submission of Northumbria all within the space of a very few years around 830, but then his "empire" shrinks back to the south. His son Æthelwulf is noteworthy in that he was a rightful heir to Wessex who actually succeeded to the throne and continued the dynasty established by his father. Æthelwulf drove off further Viking incursions and his five sons in turn had to face a major invasion. One of these grandchildren of Ecgbert was Alfred, whose troops (whether under his direct or indirect command) actually drove the Vikings out of Chester.

The status of Chester at the time that Hastein raided it in 893/4 is puzzling. The city appears to have been Welsh when Ecgbert attacked it in 828, and to have been populated when the remains of Werburgh were brought there in 876. Plegmund appears to have been living near to Chester around that time. Chester was "restored" in 907, but appears to have been already inhabited when Ingimund and his Vikings arrived in the Wirral around 902.

The identity of the sculptor who created the bas-reliefs in the Town Hall at Chester is unknown and nothing is recorded of the process by which the subjects were selected. On balance it seems that the prevailing notion at the time the reliefs were created was that Ecgbert was the "first king of England", but in reality he did not hold onto his supposed conquests. Much of his reputation as "first king" and eighth "bretwalda" could be down to Medieval and Victorian propaganda, as well as the efforts of the West-Saxon writers of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle to leave Mercia out of history. A far better choice would have been Alfred, whose forces drove the Vikings out of Chester, or even better Alfred's daughter Æthelflæd who rebuilt Chester as a burh and extended the walls of Roman Chester to essentially their present line.

Chronology

This chronology is set in terms of the rulers of Wessex:

8th Cent

- 789: Annals of Chester record "Primus Danorum educatus [adventus] in Angliam qui docuerunt Anglos nimis potare" (The first arrival in England of the Danes, who taught the English to drink too much).

- 793: Lindisfarne sacked by Vikings;

- 794: Iona attacked by Vikings (for the first of many times). Vikings sack the Monkwearmouth–Jarrow Abbey in Northumbria;

Ecgbert (771/775 – 839)

- 802: Ecgbert becomes ruler of Wessex;

- 806: Vikings massacre Columba's monks, and all the inhabitants on the island of Iona. Other monks flee to safety in the monastery of Kells (Ireland). They take with them the Book of Kells;

- 807: The Vikings land on the Cornish coast, and form an alliance with the Cornish to fight against Wessex;

- 828: Ecgbert takes Chester (briefly);

- 835: Danish Viking raiders ally with the Cornish, against the rule of King Egbert of Wessex (approximate date). The Isle of Sheppey is attacked by Vikings.

- 836: Ecgbert was defeated in 836 at Carhampton by the Danes

- 837: Battle of Hingston Down: The West Saxons, led by King Egbert of Wessex, defeat a combined force of Cornish and Danish Vikings, at Hingston Down in Cornwall;

- 839: King Egbert of Wessex dies after a 37-year reign, and is succeeded by his son Æthelwulf ("Noble Wolf") as ruler of Wessex;

Æthelwulf (839–858) Ecgbert's son

- 840: Vikings make permanent settlements with their first 'wintering over', located at Lough Neagh in Northern Ireland (approximate date).

- 841: The town of Dyflin (meaning "Black Pool") or Dublin (modern Ireland) is founded by Norwegian Vikings, on the south bank of the River Liffey. The settlement is fortified with a ditch and an earth rampart, with a wooden palisade on top. The Norsemen establish a wool weaving industry, and there is also a slave trade. An artificial hill is erected, where the nobility meets to make laws and discuss policy.

- 850: The Pillar of Eliseg is erected by King Cyngen ap Cadell of Powys (Wales), as a memorial to his great-grandfather Elisedd ap Gwylog (or Eliseg);

- 851: Danish Viking raiders enter the Thames Estuary, and plunder Canterbury and London. They land at Wembury near Plymouth, but are defeated by Anglo-Saxon forces led by King Æthelwulf of Wessex. His eldest son Æthelstan of Kent, accompanied by Ealdorman Ealhhere, attacks a Viking fleet off the coast at Sandwich, and captures nine of the enemy vessels while the remainder flees.

- 852: A Viking fleet of 350 vessels enters the Thames Estuary before turning north, and engages the Mercian forces under King Beorhtwulf. The Mercians are defeated, and retreat to their settlements. The Vikings then turn south and cross the river somewhere in Surrey; there they are slaughtered by a West Saxon army, led by King Æthelwulf and his son Aethelbald, at Oak Field (Aclea). King Æthelstan, the eldest son of Æthelwulf, is killed by a Viking raiding party. He is succeeded by his brother Æthelberht, who becomes sub-king of Kent, Essex, Surrey and Sussex;

- 853: Burgred of Mercia sends messengers to Æthelwulf, king of the West Saxons, seeking his help to subjugate the Welsh. Æthelwulf advanced with Burgred against the Welsh, and successfully repressed their "rebellion".

- 856: Æthelwulf goes on pilgrimage to Rome leaving Æthelbald in charge;

- 856: Æthelwulf returns from Rome, Æthelbald refused to give up the crown.

- 858: King Æthelwulf of Wessex dies after an 18-year reign, and is succeeded by his eldest surviving son Æthelbald.

Æthelbald (855–860) Æthelwulf's second son

- 858: Æthelbald becomes sole ruler of Wessex. His brother, Æthelberht, is left to rule Kent and the south-east of England; he marries his father's young widow Judith of Flanders (daughter of Charles the Bald);

- 859: Winter - The weather is so severe that the Adriatic Sea freezes, and Italy is covered in snow for 100 days;

Æthelberht (860–865) Æthelwulf's third son

- 860: Viking raiders led by Weland sail to England and attack Winchester (the capital of Wessex), which is set ablaze. He spreads inland, but is defeated by West Saxon forces, who deprive him of all he has gained.

- 865: Great Heathen Army arrives in Britain;

Æthelred I (865–871) Æthelwulf's fourth son

- 867: Alfred (later ‘the Great’) marries Ealhswith of Mercia. This was possibly a political marriage made in response to the Danish conquest of Northumbria the same year;

- 868: Alfred and his brother King Æthelred I go to the aid of Burgred of Mercia against a great Danish army that had invaded East Anglia. Burgred pays the Vikings off;

- 869: Bardney Abbey destroyed by Vikings;

- 870: Ely Abbey destroyed by Vikings;

- 871: Danes invade Wessex. In January, a force led by Alfred and his older brother Æthelred were defeated by the Vikings at the Battle of Reading. At the Battle of Ashdown a few days later, Alfred and Aethelred led their army to victory over the Vikings. Towards the end of January Alfred and Aethelred suffered another defeat by the Vikings at the Battle of Basing. In March, after a long and bloody battle, Alfred and King Aethelred are defeated by a Viking force at the Battle of Meretun (Marton). Æthelred died and Alfred succeeded him as Æthelred’s two sons, Aethelwold and Aethelhelm, were too young at the time to effectively rule. After the Battle of Wilton in May, the Danes were finally bought off by Alfred on the condition that they immediately left Wessex and didn’t return;

Alfred the Great(23 April 871 — 26 October 899) Æthelwulf's fifth son

- 876: Vikings at Repton (possibly with plague). Remains of St Werburgh translated to Chester. Burgred of Mercia flees to Rome. Ceolwulf II becomes "ruler" of Mercia;

- 877: The Danes enforce the partition of Mercia and occupy Gloucester for some months;

- 878: King Rhodri Mawr of Gwynedd was killed in battle probably against Ceolwulf II. In mid winter the Danes leave Gloucester and carry out a surprise attack, capturing Chippenham. Alfred is staying at Chippenham at the time and is forced to flee. In May the West Saxons defeat the Danes at the battle of Edington – they surrendered and their king, Guthrum, was forced to accept baptism and peace terms; Alfred makes treaty with Danes (Guthrum);

- 879: Death of Ceolwulf of Mercia. Æthelred of Mercia becomes ruler of ‘English’ Mercia – the south and the west;

- 881: Battle of the Conwy between King Anarawd and his brothers of Gwynedd and a Mercian army almost certainly led by Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians. The Welsh were victorious, and this contributed to Æthelred's decision to accept the lordship of King Alfred the Great of Wessex.

- 886: Alfred captures London from the Danes. However, as London is technically Mercian territory Alfred puts the city in the control of Ealdorman Æthelred of Mercia;

- 887: Æthelflæd marries Æthelred at some point between 885 and 887 – she would have been 15 - 17. Æthelred’s age is not known – but he is likely to have been notably older;

- 889: Worcester is fortified as a burh, likely on the orders of Æthelred and Æthelflæd;

- 890: Aethelstan (Guthrum), dies. Plegmund becomes Archbishop of Canterbury;

- 891: The Anglo Saxon Chronicle is begun;

- 892: Hastein arrives with new wave of Vikings;

- 894: Æþelstān born, Vikings raid Chester;

- 900: Alfred dies, Plegmund crowned his son Edward the Elder as king;