Leadworks

Roman Lead

Early evidence for "industry" in Chester points to leather, lead and linen as significant commodities traded here. Remains from Roman Chester include lead ingots, one being inscribed IMP•VESP•AVGV•T•IMP•III (the word DECEANGI appears on the side, pointing to a source in North Wales) which means it can be dated to AD74. Some examples of lead plumbing can be found in the Grosvenor Museum.

Not only did the Romans use lead for plumbing, but they used lead acetate ("sugar of lead") which they called "sapa", to sweeten wine, and richer segments of the population could consume as much as two liters a day. This may well have produced the traditional physiological effects of lead poisoning: organ failure, infertility and dementia, and it has been suggested this explains the behavior of some Roman emperors and may eventually have helped facilitate the fall of their empire. The end of the Romans was not the end of "sugar of lead": Pope Clement II died in 1047, and a 1959 examination of his remains indicated lead poisoning. That Pope liked his wine, especially those from his native Germany which were sweetened in the ancient Roman manner: it it even thought that Ludwig van Beethoven (who was "fond of a drink") may have died of lead poisoning. Lead acetate is still in use today for one other thing that the Roman's used it for: it is the principal active ingredient in "progressive" types of hair colouring dyes - used by men who want to hide greying hair.

In recent years evidence of even earlier mining has come to light with the discovery of a possibly prehistoric pestle and mortar, found underground in the Minera mines, and a hammerstone on the south-west side of Ruabon Mountain, at World’s End.

The "Lead and Crime" hypothesis: that high levels of lead contribute to social disorder, has been advocated by numerous academic studies and various criminologists, with the research coming to complex, disputed results. Lead poisoning is widely understood to have highly negative results in multiple parts of the human body, particularly the brain. Concerns about even low levels of exposure began in the 1970s; currently, scientists have concluded that no safe threshold for lead exposure at all exists. The problems are particularly acute for children. Notably, the parts of Chester near to the Leadworks, particularly Canalside and Boughton were reknowned for their criminality (see: Black Sunday), but this could have had many other causes, including alcohol and poverty.

For most people, the major source of lead exposure was from lead added to petrol as tetra-ethyl lead (now banned). This use was invented by Thomas Midgley in the US. His second major contribution to civilisation was the chlorofluorocarbon, or CFC (now banned), which improved refrigerators, but destroyed the ozone layer. In middle age, afflicted by polio, Midgley applied his inventor's mind to lifting his weakened body out of bed. He devised an ingenious system of pulleys and strings. They tangled around his neck, and killed him. Bill Bryson remarked that Midgley possessed "an instinct for the regrettable that was almost uncanny."

"Modern" Lead

Following the departure of the Romans lead had been mined at Minera since at least the 13thC (when Edward I recruited miners from Minera to work in Devon). In the medieval period, lead was needed for roofing castles and churches. During the fiftheenth century, following the revolt of Owain Glyndŵr, the mines fell into disuse, and mining was at a low ebb for two centuries. During the 17th century the industry gained in importance. A new mill at Mold was built in 1661 and output doubled, but from the 1670s smelting operations became more concentrated on Deeside, probably due to better transport links by using the River Dee. One of the best examples of this is from the early 18th century when the Quaker London Lead Company built a large smelting house at Gadlys at Bagillt.

The Grosvenors were involved in the lead industry in North Wales. In 1589 the Crown granted the mineral rights in the lordships of Coleshill and Rhuddlan (Halkyn Mountain forms part of this) to a William Ratcliffe of London. In 1597, the same William Ratcliffe was granted a lease of a lead-smelting mill and a small plot of land called "Y Thole" by Edward Lloyd of Pentrehobin. (Indicating that the industry was already established). By the end of the 16th century, Radcliffe was sending pigs of lead from his smelter at Mold to his warehouse in Watergate Street, prior to being shipped out to London via the River Dee Estuary. Radcliffe also took his lead directly from his Mold smelter to an anchorage at Wepre Pool on the Dee. These two rights were then sold to Richard Grosvenor in 1601 and thus began the family's connection with lead mining. Around this time they also accumulated the mineral rights in the lordships of Bromfield and Yale in Denbighshire. These acquisitions enabled this family to control a huge swathe of the industry in the Mold area. The Grosvenor appreciation of the potential of North Wales mineral resources may have been enhanced following the marriage in 1628 between Sir Richard Grosvenor (2nd baronet) and Sydney Mostyn, daughter of Sir Richard Mostyn whose estates included much of Flintshire‟s rich deposits of lead, silver, zinc and coal. From the 17th century the lead mines in the areas controlled by the Grosvenors gave substantial financial returns, so much so that the term “Grosvenor Mines” became synonymous for wealth. Other landowners were attracted by the prospect of good returns. The Hughes family of Trecastell owned and worked the lead mine at Talargoch near Prestatyn in 1573. In 1642, the Myddletons of Chirk Castle were partners in one of the Grosvenor mines at Maeshafn in the Alyn Valley. The lead was smelted locally. In 1602 lead ore from the Halkyn area was being smelted at Thomas Jones mill at Flint and the lead produced sent by sea to Bristol and Holland. Thus the expansion in lead mining in Flintshire after 1660 was triggered not only by good market conditions but also the initiative of local landowners. The huge costs of lead mining incurred through greater investment in draining the mines and processing greater quantities of ore was met to a great extent by cooperation between landowning families such as the Grosvenors, the Myddletons and Mostyns together with wealthy local merchants.

From the early days of this industry, the mine owners found it necessary to import labour and expertise from more well-established lead-mining areas, mainly from Cornwall and Derbyshire. These workers operated under the laws pertaining to these other districts whereby the miners kept 90% of the ore and gave the owner or lessees the remaining 10%. This was a situation that Sir Richard did not find to his liking and around 1619 he embarked on a course of litigation against the miners who had petitioned that they had been forbidden to work the mines and been forced to sell to the Grosvenors at his price. This case resulted in victory for Sir Richard in the Court of Star Chamber (its famous ceiling is now at Leasowe Castle on the Wirral) in 1623. Lead from the mines was brought to Chester for storage at a warehouse and onward sale.

His grandson Thomas Grosvenor was involved peripherally in London's first stock market boom. In 1687 there were fewer than fifteen English joint-stock companies (Hudson Bay co ..etc). The shares of those companies were held in relatively few hands and were traded infrequently. Yet, by 1691, London’s stock market was booming. One company concerned was "Estcourt’s Lead Mine". The actual mine was owned by Sir Thomas Grosvenor who, disappointed by the local miners’ inability to exploit it, granted the mining rights to his ‘cousin and friend’ Phineas Bowles, a prominent London broker and stock-jobber, and John Blunt another stockbroker. Neither knew anything about lead-mining, but they found an ingenious way to make money from the mine by literally "turning lead into gold". Bowles, Blunt and Sir Thomas Estcourt, apparently without Grosvenor’s knowledge, turned the project into a joint-stock company nominally headed by John Lethieullier (a noted lead and tin exporter). An unexplained rise in stock price from around £10 to over £100 in late 1693 and early 1694 (by mid-1694 shares were being quoted at £150) apparently confirms that the lead company was used for what might be called "speculative purposes".

In brief, in the initial share offering options were taken to buy the £10 shares back at £20 after a short time - even if they were worth less. This seemed a tempting offer as the shareholder apparently could not lose. The share price in "Estcourt’s Lead Mine" was then manipulated by brokers (circulating rumours using coffee-houses - the internet of the day) to push it up, when the options were called upon and the now far more expensive shares bought back at a cheap price - these were quickly sold to "greater fools" before the bubble burst. Interestingly this was before the South Sea Bubble (1711–1720: notably Blunt was a close relative of a chief architect of the South Sea Bubble) and although there had been earlier asset bubbles such as the Dutch "Tulip Mania" (1634-1637) it may have been one of the first actual share bubbles and an early example of both "hedge" dealing and sophisticated stock-market manipulation.

A lead mine was discovered on property forming part of the Owen Jones bequest to the City Guilds around 1744. Lead prospecting was promoted by Alderman Richardson of Chester. Between 1761 and 1781 the city companies had received nearly £13,000 in royalties. Owen Jones is remembered on the facade of the once Grosvenor Club at the Eastgate - passed by many people every day without a second thought.

In the later 18th Century prospectors had learned how to find the underground reserves of lead. However, deep mining had its problems because of flooding as lead veins are in limestone and limestone means underground rivers. Pumping water out was very costly and a major obstacle to any successful deep mining for lead. The man with the solution was John "Iron Mad" Wilkinson, an entrepreneur (he built the world's first iron boat) and the brains behind nearby Bersham Ironworks. The main product of the Ironworks was producing cannon and steam engine cylinders. Bersham was the first site in the world to use a new way of boring holes in cannon and steam engine cylinders. Wilkinson’s used these steam engines to keep the Minera mines free of water and Lead mining at Minera was once again profitable. However, Wilkinson copied the design of the Boulton and Watt steam engine, having been supplied with one in April 1776. He did not tell Boulton & Watt that he had copied their design, but John Wilkinson and his brother William eventually fell out and William informed Boulton and Watt that brother John had pirated their designs. They sued and Wilkinson had to pay up, which led to another feud between the brothers in which each of them tried to wreck the Bersham works to prevent the other from possessing it. These and other problems led to a decline in mining at Minera over the next few decades.

sources and links

- International Political Economy details the "Lead bubble";

- Chester Landscape History on lead mine ownership;

- Industry in Fflint;

Leaden Commerce

Leadworks typically produce both sheet lead and compounds of lead.

- White lead is the chemical compound 2PbCO3·Pb(OH)2, a complex chemical compound, containing both a carbonate and a hydroxide portion. White lead occurs naturally as a mineral, in which context it is known as hydrocerussite, a hydrate of cerussite. It was formerly used as an ingredient for lead paint and a cosmetic called Venetian Ceruse. Its opaque quality and the satiny smooth mixture it made with driable oils made a good pigment. In the eighteenth century, white lead paints were routinely used to repaint the hulls and floors of Royal Navy vessels, to waterpoof the timbers and limit infestation by "teredo navalis" worms. However, it tended to cause lead poisoning, and its use has been banned in most countries. The production process involves the reaction of lead with acetic acid (in earlier days, vinegar). Another material used in the process was tanners bark of which Chester had a ready supply due to the Skinner's activities. Another important ingredient was horse-shit, which Chester could presumably supply in sufficient quantity.

- Red Lead is the chemical compound Pb3O4, or 2 PbO·PbO2 (Lead (II, IV) oxide), also called minium or triplumbic tetroxide, is a bright red or orange crystalline or amorphous pigment. Red lead is used in the manufacture of lead glass and rust-proof primer paints (now mostly banned due to toxicity). The combination of minium and linen fibres was also used for plumbing (now replaced with PTFE tape). Lead (II, IV) oxide is prepared by "calcination" of lead (II) oxide (also called litharge) in air at about 450 to 480 °C.

The traditional method making white lead was the "Dutch Stack" process (although the Roman method for making sapa was similar). Hundreds or thousands of earthenware pots containing vinegar and lead were embedded in a layer of either tanners bark or cow or horse dung. The pots were designed so that the vinegar and lead were in separate compartments, but the lead was in contact with the vapor of the vinegar. The pot was loosely covered with a grid of lead, which allowed the carbon dioxide formed by the fermentation of the tan bark or the dung to circulate. Each layer of pots was covered by planks and a new layer of tanners bark, then another layer of pots. The heat created by the fermentation, acetic acid vapor and carbon dioxide within the stack did their work, and within a month or so the lead was covered with a crust of white lead. This crust was separated from the lead, washed and ground for pigment. This was an extremely dangerous and unpleasant process for the workmen. Medieval texts warned of the danger of "apoplexy, epilepsy, and paralysis" from working with lead white. Surprisingly, the same process was still in use at Chester until 1938.

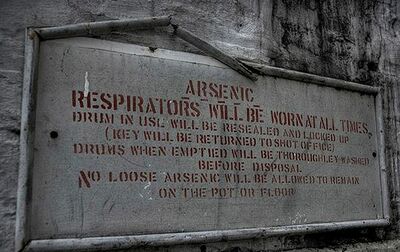

For many years both lead and arsenic were used to make paints. "Scheele's Green" (also called Schloss Green) is a cupric hydrogen arsenite (also called copper arsenite or acidic copper arsenite). One of its uses was as a decorative wash for papered or bare plaster walls. When the wall becomes damp and moldy, the pigment may be metabolised, causing the release of poisonous arsine gas (AsH3) as a way for the mold to get rid of the toxin. This green pigment may have been produced in Chester, as there are stories of finding the toxic green wash on the basecoat of plaster when renovating Victorian properties in the city. The leather making industry, once a major industry in Chester, used to soak animal skins in a lime and arsenic slurry to soften them and remove hair prior to Tanning. Arsenic may therefore be associated with any animal hair within plaster: put into the plaster to prevent cracking. Lead carbonate and other compounds were used widely in oil-based paints until the 1960s owing to their capacity for improving permeability and elasticity and it is still found widely in historic buildings - as in Chester. Despite being banned from sale in 1992, its controlled use is still permitted for use on Grade I and Grade II* buildings, where alternative materials are not appropriate.

The Walkers

In 1778 Samuel Walker (1715-1782), in partnership with Richard Fishwick and Archer Ward of Hull, began a white lead manufacturing business at Elswick, near Newcastle-upon-Tyne. Samuel was the second son of Joseph and Ann, was only 13 when his father died. He qualified himself for keeping a School at Grenoside, until 1746, where he taught reading, writing, and arithmetic. In addition, Samuel supplemented his living by land surveying, and making sun dials. The Walkers had a family foundry and about 80 of the 105 guns aboard HMS Victory at the Battle of Trafalgar were cast by the Walker Company in Rotherham.

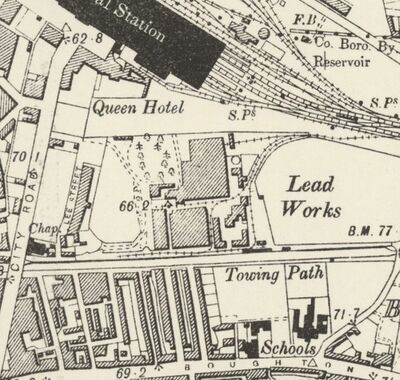

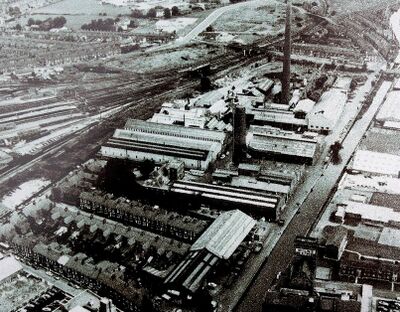

Samuel Walker provided most of the capital for the leadworks, while his partners contributed business and practical expertise. The original proposal was for a riverside location at Edgar's Field - the site of the Roman Minerva Shrine. However plans were changed to locate the works at Canalside. Construction of the shot-tower began in, and was completed in, 1799. This enterprise was extended, producing not only white and red lead but also pipes. Rising prices for lead encouraged many others to enter this trade about this time. In 1802 Samuel Walker Parker joined the lead partnership, which then became known as "Walker, Parker and Co".

A later member of the family, Sir Edward Samuel Walker (1799-1874), educated at Rugby and St. John's College Cambridge, was a partner in the "Lead House" of Walker, Parker & Co., Chester, managing their factory there and at Baglit. He was Mayor of Chester in 1838, being knighted while in office, in 1841 and 1848. He was also JP for Chester and Cheshire. The leadworks at various times traded under names reflecting its shifting ownership between various combinations of Walkers and Parkers, and in the 1850's there was a noted law-suit in the US (Pollen v. Le Roy) in which the dubious argument hinged on whether lead marked "Walker and Parker" needed to be paid for if ordered from "Walker, Parker and Walker".

Shot Tower

William Watts of Bristol (originally listed in his tax returns as a plumber) took out a patent (number 1347, filed 10th December 1782, granted on March 28th, 1783) for his new technique for making lead shot, a process:

- "for making smallshot perfectly globular in form and without dimples, notches and imperfections which other shot hereto manufactured usually have on their surface".

According to a legend (of which there are many versions - including the unlikely tale of a church burning down), William Watts, while watching the rain fall, possibly in a dream, noticed that the raindrops formed perfect spheres as they fell. Watt's patented technique, was to allow molten lead, to which the deadly poison arsenic had been added, to be poured from the top of a tower, passing through a griddle to separate it into pellets which plummeted (literally) downwards before landing in a wooden vat of water below. Watts adapted his house on Redcliffe Way by adding a three-storey tower and digging a shaft under the house through the caves underneath to achieve the required drop. During the fall the pellets became spherical and harden and the various sizes obtained could be graded using sieves. Whatever, the truth, Watts' shot was very regular and smooth, unlike the lead shot produced by a moulding process, which had a ridge where the mould parted. This led King George II to remark of it:

- "I wish all the men in my army were so regular like this shot"

Chester has a further interesting connection with George II - a detachment of the Cheshire Regiment was present at the Battle of Dettingen in 1743, during the War of the Austrian Succession. George II’s horse "bolted" during the battle and ran away. George is said to have "sheltered" under an oak and to have presented an oak leaf to the soldiers who looked after him. The Cheshire Regiment claims this honour (even though they were in garrison in Minorca at the time - a detachment was present at the battle). Dettingen was the last time that a current English monarch had personally lead his troops into battle.

The hardness of lead shot is controlled through adding variable amounts of tin, antimony and arsenic, forming alloys. Usually, only minor amounts of these are needed. The addition of arsenic also keeps the lead molten for longer as it falls, forming a more spherical shot. For the so-called "drop shot" or "soft shot", arsenic comprises about 0.1%wt of the finished projectile. The remaining percentage is lead of relatively high commercial purity. If less arsenic is used, the melted pellets do not form into substantially spherical form as they drop from the shot tower pan. To make the so-called "chilled shot", antinomy to the extent from about 1%wt to 5%wt is added. Pellets of a lead/antimony alloy are harder than pure lead and are believed to retain their shape better when discharged from a shotgun.

A Leadworks was initially established by the Chester Canal (by "Walkers, Maltby and Company") in the 1780's and its shot tower, dating from 1799 (Watts' patent having just expired) was used for making lead shot for the Napoleonic Wars. It is the oldest remaining shot tower in the UK. The Cheese Lane Tower in Bristol, a reinforced concrete tower, was constructed in 1969 to replace Watts' original shot tower in Redcliffe, which was demolished in 1968.

The circular red-brick tower at Chester is 168 feet (41.2m) tall and 30 feet (9.1m) in diameter at the base tapering to 20 feet (6m) at the top, with small arched windows. It remains to this day the tallest structure in Chester (the Cathedral is a little shorter at 127 feet (39m)). A lift shaft dating from 1971 remains attached to the exterior. The interior retains a rickety spiral staircase/ladder. The Cheshire Sheaf of May 1878 published the following from from Bryan Johnson of King Street, indicating the presence of a second shot-tower in Commonhall Street:

- "As my father was manager of these works for many years, and as I was born in the house now occupied by Mr. A.O. Walker at the works, I maybe allowed to say a few words on the subject. My father came to Chester in the year 1800, and found the Shot Tower just commenced upon, the foundations being built, and he superintended the completion of the Shot Tower as well as the other buildings. He continued manager to Messrs. Walker, Parker, and Co., until Sir Edward Walker came to reside in Chester, about 1830. I think I have heard that when Messrs. Walker, Parker, and Co., first thought of establishing works in Chester they had almost decided upon Edgar's Field, Handbridge, as the locality; but, as the "Ellesmere and Chester Canal" was just at that time nearly ready to be opened, the present site was considered to be the best. There was, as will be remembered by some, a Shot Tower and Lead Works in Commonhall Street; but these were not, so far as I understand, so old-established as Messrs. Walker's works".

By 1812, the leadworks is known to have also included pipe-drawing machines and a rolling mill for producing lead sheet. According to some (perhaps unlikely) reports the top of the tower could sway considerably in high winds, sometimes causing the falling lead to miss the tank of water at the bottom.

Sources and Links

- Chester Walls on the shot tower and leadworks (many photographs);

- More from Chester Walls - on the theft (and recovery) of the Leadworks clock;

- The Shot Tower in Bristol;

A Missing Racehorse?

Judy Egerton's book, "British sporting and animal paintings 1655-1867" (London, 1978) is quoted on the Chester Walls site as:

- “Euphrates, a chestnut colt by Quiz out of Persepolis, was bred by Lord Rous and foaled in 1816. He won numerous races and, after several changes of ownership, was purchased by John Mytton, squire of Halston near Shrewsbury, a famous and eccentric sportsman, for whom he continued to win trophies, including the Gold Cup at Lichfield in 1825- a victory commemorated in this painting [by my ancestor, William Webb]. He continued to race until he was thirteen years old. By then Mytton was heavily in debt... everything was sold except Euphrates. Mytton entrusted him to a friend, requesting that the horse should be shot rather than end his career by being "put to the drudgery of drawing a coach, or any other ignoble purpose". He was duly shot in June 1832 and a memorial over his grave near the Shot Tower at Chester Lead Works commemorates his achievements" (page 235).

The same information turns up on "Grave Matters", which records:

- Euphrates (c. 1816-1832; buried near the Shot Tower, Chester Leadworks)

"Mad Jack" Mytton (30 September 1796 – 29 March 1834) was certainly an eccentric (see the references below). He inherited vast wealth (several millions in today's money) at the age of two, was sent to Westminster School, (he was expelled after one year for fighting a master at the school), then sent to Harrow School (he was also expelled, after just three days). He was then educated by a disparate series of private tutors whom he tormented with practical jokes that included leaving a horse in one tutor's bedroom. Despite having achieved nothing academically, Jack was granted entry to the University of Cambridge, to which he took 2,000 bottles of port to sustain himself during his studies (given the length of the term at Cambridge that is over four bottles a day). He left without a degree of any kind - which was actually quite difficult given that one gets a "pass" degree simply by staying the course.

In 1819, aged 23, he entertained ambitions of standing for Parliament, as a Tory. He secured his seat, encouraging his constituents to vote for him by offering them £10 notes and through spending £10,000 (almost a million today) and became MP for Shrewsbury. He found political debate boring and thus attended parliament only once, for just 30 minutes - at a cost in today's money of around £500 a second. "Mad Jack" once turned up at a party riding on the back of a bear. The English nobleman, despite his staff’s best efforts, could not curb his debt. His agent even calculated that if he could reduce his spending to $6,000 a year, he could keep his estate and be fine, but Mytton had no interest in that. In 1831, he ran away to France to escape his creditors. While there, he began to get quite sick. In 1833, he returned back to England, and, since he still had mountains of debt he couldn’t pay, he was immediately interred in the King’s Bench Prison in Southwark. He died there in 1834 (aged just 38) and still deeply in debt, from liver disease.

But no-one has ever found the exact location of the grave of "Euphrates".

Just why Mytton should chose Chester as the place to bury his horse is also a bit of a mystery. The only connection with Chester appears to be that some of the same branch of the Mytton's were according to Ormerod rectors of Eccleston.

Sources and Links

- "Mad Jack" Mytton and his horse Euphrates from the "New Sporting Magazine", November 1834;

- A Memoir of "Mad Jack";

- A pub, named after bear-riding "Mad Jack";

- More on "Mad Jack";

- William Webb, ca. 1780–1845, British, Euphrates, 1825;

Development and Decline

In the late 19thC. the leadworks at Chester continued to specialize in white lead production, which by 1890 took up over half the operational site. The production of lead shot also remained important, and Chester benefited from the decline of the firm's Bagillt works as the increasing import of overseas lead undercut ore produced, smelted, and refined in north Wales. The transfer of lead milling to Chester was completed in 1909, and shortly before the First World War the decision was taken to open a new lead refining plant. Finally, in 1929 the smelter was moved from Bagillt to Chester and the north Wales works closed completely. The production on the site of acetic acid for the white lead process was closed down before 1900 because synthetic acid could be bought in more cheaply.

In the 1880s the Walkers Parker partnership was destroyed by an acrimonious dispute between two of the partners, one of whom was manager of the Chester works and had spent a considerable sum of money improving the onsite managers house. In 1889 the new limited company of Walkers, Parker & Co. bought out the partners' assets and took over the Chester works. This transfer came at a time when trading conditions in the lead industry were difficult, and the new concern's financial performance was poor throughout the 1890s. Parts of the site were sold to improve the financial position - it has been said in one local history that the Queen Hotel and some terrace houses were built on this land, although the Queen Hotal was known to have opened on the 21st April 1860. Employment grew only slowly between 1880 and 1914 before expanding dramatically during the First World War. In 1921 red lead smelting and refining was taking place at the leadworks, the largest supplier being the Bagillt Works which Chester had purchased in 1830. In 1899 a fire broke out at the lead works which was described as “great damage, magnificent spectacle”. Due to misunderstanding and maladministration it took two hours for the private fire brigade to arrive. After this incident it was decided that such an essential service should be run by the City council (see: Fire Station).

Walkers, Parker and Company, became part of Associated Lead Manufacturers in 1924, with the latter in turn later becoming part of the Calder Group. As well as producing lead, lead compounds and lead-based paint, the site also produced antimony oxide, the main application for which was as a flame retardant helping to form less flammable plastics and foams. Such flame retardants are found in electrical apparatus, textiles, leather, and coatings. The factory was upgraded with improved office and laboratory facilities and amenities for staff, such as showers. By 1975 it was a self-sufficient, fully integrated lead works capable of smelting ore (and recovering significant quantities of silver) as well as producing finished goods, although paint manufacture had stopped in 1963.

Over time the situation changed; the works was very close to residential areas and the city centre and there was concern over environmental issues. Court cases relating to pollution and noise from the works had been reported in the local press since the 19thCent. Despite the very high chimney built in 1958, and visible on many photographs of Chester from the 1960's, the "fall out" would have been landing on Hoole under prevailing wind conditions (from the south-west). Recycling of used lead containing products, such as car batteries, was a particular problem - as these were at times simply thrown whole into the blast furnaces. There was also difficult access for large vehicles, especially due to weight restrictions on the canal and railway bridges in Hoole Lane. In addition there was duplication of facilities across other company sites belonging to Associated Lead Manufacturers. These reasons, together with high city center land values, brought about a planned closure for 1982. There was a reprieve for special products which continued to be produced until 2001 when production was moved to Sealand Road. Lead shot is still made at Sealand Road, but this is a special small shot used in the production of particular kinds of steel. There is no shot-tower at Sealand Road as the current "state of the art spinning" process (invented in Chester) does not need one.

Another innovation put into production at Chester's Leadworks was "lead coated steel". This was for cladding of buildings with rust free external panels and was a fore-runner to the cheaper plastics/aluminium panels which were used more recently (to disasterous effect due to flammability). These innovative lead/steel panels are used on the bell-tower at Chester Cathedral, but were more visible on the mansard roof of "Windsor House", an office block (with shops on the ground floor) of 1974-5 by John Taylor of Edmund Kirby and Partners, at the corner of Pepper Street and Lower Bridge Street - the roof was removed during renovation work in 2017-18. The panels were manufactured by pressure rolling pre-treated steel sheet, which has been dipped in terne (an alloy of lead and tin) together with lead sheet with sufficient force to ensure both that there is cohesion without the need for adhesive and that the lead spreads to form a thin cohesion-resistant film. This type of material has all the advantages of a medieval church roof made of lead sheet, but much less weight (and is less likely to be stolen).

The Resolution class submarine was the launch platform for the United Kingdom's strategic nuclear deterrent from the late 1960s until 1994, when it was replaced by the Vanguard-class submarine carrying the Trident II. The class comprised Resolution, Repulse, Renown and Revenge. They were built by Vickers Armstrong in Barrow-in-Furness and Cammell Laird in Birkenhead between 1964 and 1968. The lead reactor shielding of these boats, together with the reactor shielding of the earlier US/UK HMS submarine Dreadnought (S101), was manufactured at the Leadworks in Chester. On 3 March 1971, Dreadnought became the first British submarine to surface at the North Pole.

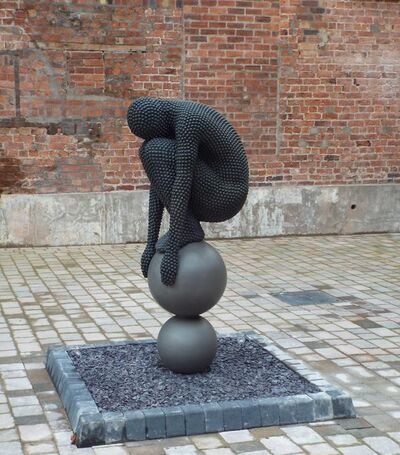

When the leadworks closed in 2001, the shot-tower had been in use up to that time, making at various times ball-shot, shotgun-shot, special steel-makers shot and even fishing shot. Many of the remaining buildings of the leadworks, with the exception of the shot tower, were demolished around 2004 to make way for urban regeneration of the Canalside area. A (very) small park by the canal "close to" the former site was opened in May 2006. The park (which is actually on the other side of City Road) contains a sculpture in stainless steel and blue glass which commemorates Chester's lead industry; 'Spheres of Reflection' by Edd Snell. It was inspired by "lead drops impacting on the surface of water" - although in the actual process the hight of the shot tower ensured that the shot had solidified before it hit the water.

Redevelopment

At the end of 2007, Property Regeneration Group was granted planning permission and announced that redevelopment of the site was underway. The scheme was to comprise 33 one- and two-bedroom apartments — including an element of ‘affordable housing’ — together with 27,000 sq ft of commercial space for offices, bars and restaurants and other purposes. Most of the remaining buildings around the tower were to be demolished and the tower itself would figure as the main entrance to the upper floor flats in a four-storey extension. In mid-2008, advising engineers for the project, Chester-based consultancy Gifford stated that they themselves would move into new offices in the complex once construction work was finished. At the time, work was scheduled for completion in the autumn of 2009. In November 2008 planning permission was granted for revisions to the proposals in which changes had been made to suit the requirements of the principal potential commercial occupier. The level of affordable housing was also reduced from the original seven dwellings down to four. Property Regeneration went into administration in 2009.

In July 2011 new plans were announced by Liverpool-based Neptune Developments. These again featured housing, bars and restaurants and shops, but also include a heritage aspect and a new bridge over the canal, linking the complex with the Waitrose supermarket nearby. Planning approval for redevelopment of the site was eventually granted in October 2012, but not without considerable debate and outcry. CWaC councillor for Boughton, Cllr David Robinson said:

- "Once consent is given and it is built we will have to live with this every single day. It has been described to me as something like a prison scene from the Italian Job and over the past week someone asked me if it was a car park being built."

In December 2015 a fire broke out at the shot-tower, believed to be caused by an electrical fault connected with the "O2" mobile phone antennae. Fortunately, this time the Fire Service did not take two hours to arrive and the structure of the tower was apparently not compromised. As of August 2017, construction work is yet to start, and the remaining buildings - the core of the original works around the shot tower - are in a poor state of repair.

The Falcons

The shot-tower is presently Chester's highest structure, although the chimney which previously stood on the Leadworks site was even higther. The top of the tower has been for some years (as of 2020) the home of pair of breeding Perigrine Falcons. A pair mates for life and returns to the same nesting spot annually. The peregrine is renowned for its speed, reaching over 320 km/h (200 mph) during its characteristic hunting stoop (high-speed dive), making it the fastest bird in the world, as well as the fastest member of the animal kingdom.

Somewhat surprisingly, the pidgeon comes in at number seven, with 2-6th places being the Golden Eagle, Needletail Swift, Hobby, Mexican free-tailed bat (the fastest non-bird species) and the Frigate Bird. Pigeons have been clocked flying 92.5 mph (148.9 km/h) average speed on a 400-mile (640 km) race. Unfortunately, the Perigrine can outfly them and up to 80% of the diet of peregrine falcons in several cities that have breeding falcons is composed of feral pigeons. The fastest land animal is the cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) - estimates of the maximum speed attained range from 80 to 128 km/h (50 to 80 mph), well less than half the speed of a Perigrine and probably closer to a third as fast.

Lead and Health

The lead–crime hypothesis is the proposed link between elevated blood lead levels in children and increased rates of crime, delinquency, and recidivism later in life. Lead is widely understood to be highly toxic to multiple organs of the body, particularly the brain. Individuals exposed to lead at young ages are more vulnerable to learning disabilities, decreased I.Q., attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and problems with impulse control, all of which may be negatively impacting decision making and leading to the commission of more crimes as these children reach adulthood, especially violent crimes. No safe level of lead in the human bloodstream exists given that any amount can contribute to deleterious health issues.

Lead levels in Chester in the area around the leadworks and in children of leadworkers were some of the highest in the country (see Quinn, page 426, table 5), and higher than those found in children living near major roads.

Update 2021

A new sculpture in bronze and stainless steel was unveiled at the Shot Tower development, it is called "Mr Walker" and is by the Chester-based artist Colin Spofforth. The figure in the sculpture is encrusted with balls that represent the lead shot made at the works. The bronze sculpture is mounted on two stainless steel spheres. We do not know which "Mr Walker" this is, in 1851 Edward Claudius Walker was the tenant of Brook Lodge in Hoole. Then aged 25, occupation lead merchant, he went on to run the Leadworks where he was chief resident partner in the firm Walker, Parker & Co. According to the probate he died, aged 43, at Brook House, Clapton in the parish of Hackney: this was used as a private madhouse from 1759 to 1940.

Sources and Links

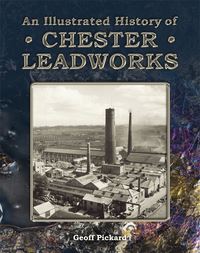

Update August 2017: Geoff Pickard (he of the broken link below) and ex works manager at the Leadworks has written an excellent (one could say weighty) but very readable and well-illustrated biography of the Leadworks (cover shown left), from its origins to the present day. The book features many previously unseen photographs to show how the site and working practices developed over the years and some now quite comical past advertising for something as apparently dull as lead. It is available from the Tourist Information office at the Town Hall and sure to sell-out soon (the first few copies are signed by the author). If you want/need to know more about the Leadworks than is written here, then buy this book.

- Chester Walls on the shot tower and leadworks - many photos;

- More from Chester Walls - on the theft (and recovery) of the Leadworks clock;

- 28dayslater on the shot tower (photos);

- More from 28DL;

- Comments by the Chester Archaeological Society;

- Other photographs from GeoTopoi;

- Geoff Pickard on the leadworks (broken link due to inconsistent website management);

- Bristol Shot Tower redevelopment;

- "Mad Jack" Mytton and his horse Euphrates from the "New Sporting Magazine", November 1834;

- 2016 progress?

- Old Welsh Newspapers on the Leadworks - with some quite funny cases about pollution;

- Leadworks in the Chester Chronicle - mostly about the "planning" issues;

- The Leadworks at Bagilt;

Drone Footage

Shot Tower