Crossley

Life

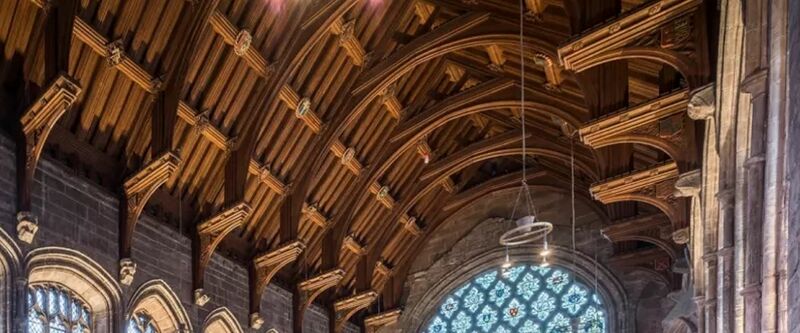

Frederick Herbert Crossley FSA (2 August 1868 – 6 January 1955), known as Fred Crossley or Fred H. Crossley, was a British wood carver, designer and an authority on Medieval English architecture, church furnishings and also timberwork. Together with Thomas Rayson, he designed the Chester War Memorial in the grounds of Chester Cathedral and later worked on the restoration of the Cathedral Refectory, designing and overseeing the installation of its new "arch-brace and hammer-beam" roof in 1939. Crossley published extensively and, in 1946, a study of Welsh rood screens he undertook in conjunction with Maurice Ridgway was awarded the G. T. Clark prize. At some early point Crossley moved to Shavington Avenue, Hoole and was still living in Hoole at the time of his death.

Crossley was born in Yorkshire in 1868, moving to Cheshire in 1887. He started his working career as a farm apprentice near Knutsford. After taking local courses in wood carving, given by the wife of the Vicar of Over Tabley, he gave up farming and pursued this interest for the rest of his life. He attended the Manchester School of Art during the 1890s undertaking further part-time studies in wood carving, drawing and design. In 1898 Crossley was appointed a teacher of drawing and wood carving by Cheshire County Council and gave up farming. The taught wood-carving in the winter months in the villages around Cheshire. He also undertook commissions for wood carvings and examples of his work can be seen in various churches in Cheshire at Over Peover, Bunbury and Plemstall. In Crossley's obituary for the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, the author, Percy Culverwell Brown, refers to the fact that Crossley became an "ardent photographer" and, in the obituary for The Antiquaries Journal, he is described as "easily the finest photographer of architectural detail of his time". Not only did Crossley use his photographs, together with plans and drawings he executed, in his books and articles, but was generous in making prints available to students.

In 1927 Crossley found himself in serious trouble. His home in Chester was raided by the Police who found a number of photographs of "young men" in "artistic" poses. The Cheshire Observer of June 7th reported the resulting court proceedings. Crossley had somehow become involved with an "artist" named John Clarke of Peckham, London, and had provided him with the images. Clarke appears to have re-sold them as pornography, of which he had a large collection. Crossley was fined £100 and Clarke got 2 years Hard Labour. Crossley appears to have been considered largely innocent, except of bad judgement, but this may have led to a reduction in his photographic activity.

Fred Crossley’s connection with the Chester Archaeological Society began when he joined it in 1916 (some sources say 1915). In March, 1920, he was elected a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, in 1921 a member of the Council of CAS and in 1923 he was giving four of the lectures out of a total of nine. Unfortunately these were never printed in the Journal. He was elected to honorary membership in 1946.

In 1932, following shortly after the "Chester Photography Case", he donated his large collection of negatives, totalling some 10,000 (some sources say 12,000), to The Courtauld Institute of Art in London where his photographs are held in the Conway Library.

Works

Crossley was the author of many books and articles. His books include "English Church Woodwork" (1917), "English Church Monuments" (1921), "The English Abbey" (1935), "English Church Craftsmanship" (1941), "English Church Design, 1040-1540 A.D." (1945), "Timber Building in England" (1951), and "Cheshire" (1949), one of the most popular volumes in the County Series published by Messrs. Robert Hale. The last of these condemns much of the modern architecture of Chester in his typically blunt Yorkshire style.

Style Argument

In many of his works Crossley is highly critical of Victorian church artitecture, claiming that the "restoration" of buildings during the Gothic Revival was actually embelishment and redesign rather than repair in a true medieval style. In the process of this Victorian "restoration", much of the original English Gothic architecture of the Middle Ages was lost or altered beyond recognition. It is estimated that around 80% of all Church of England churches were affected in some way by the restoration movement, varying from minor changes to complete demolition and rebuilding.

Crossley was particularly critical of the Victorian understanding of the supposed evolution of styles during the Early English (c1200-1290); Decorated (c1290-1350); and Perpendicular (c1350-1530) periods and appears to have been particularly unhappy with the restoration of Chester Cathedral. George Gilbert Scott's work on the Cathedral has been described as "rebuilding" rather than restoration. While Scott claimed archaeological evidence for his work, in 1872 the dean (John Saul Howson) felt compelled to defend himself against the charge of "destroying the past, and erecting a new building". Scott added the flying buttresses, the parapets along the lines of the roof, the many pinnacles and the gargoyles - none of which appear to have been part of the original plans and which mostly derive from Victorian ideals and theories.

He also disliked Modernism.

Works

His articles and papers are too numerous to list, but they can be found in the volumes published by the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society and The Chester and North Wales Archaeological Society, as well as in the pages of other learned societies up and down England and Wales.

The following papers are available from the Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire & Cheshire:

- Vol. 68. Stallwork in Cheshire.

- Vol. 69. The Church Screens of Cheshire.

- Vol. 70. On the remains of mediaeval Stallwork in Lancashire.

- Vol. 76. Mediaeval monumental effigies in Cheshire.

- Vol. 91. The post-Reformation effigies and monuments of Cheshire.

- Vol. 92. The Timber-framed Churches of Cheshire.

- Vol. 95. Church building in Cheshire during the Thirteenth Century.

- Vol. 97. Designs in Screens and Stallwork found in the borderland of England and Wales

A list of works with links to PDFs is available from the Archaeology Data Service.

Sources and Links

Related Pages

- Cathedral: Crossley did the Refectory roof and the War Memorial outside;

Online

- Frederick Herbert Crossley on Wikipedia

- some works;

- Obituary: Fred H Crossley: Journal of the Chester Archaeological Society 43. Vol 43;