Comet

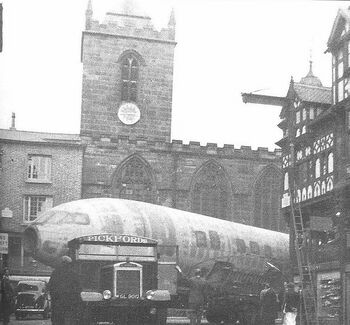

One often reproduced photograph of Chester shows a Pickford Scammell towing a DeHaviland Comet around the corner of Eastgate Street and Upper Bridge Street at the High Cross in 1955. Fortunately, it did not have to avoid the actual Cross, which was only restored to its present site in 1975, and when the photograph was taken was still in the "Roman Gardens". It is often written or said that this was a frequent sight in the City. In fact, this was an almost unique event which only occurred on two occasions as a result of desparate circumstances following a series of fatal air crashes. Like the photograph itself, the aircraft crashes have gathered much mythology over the years. One BBC website article reported a "witness" saying:

- "I remember being taken as a child on a school trip to a de Havilland factory just outside Chester in Cheshire, England. I believe the factory was in Hawarden. This was in 1954 when the Comet air disasters were happening. The factory either built the Comet or key components, there were large signs that said "This washer was missing and caused the ???? crash" (I can't remember the crash details). Because of the many signs there seemed to be an emphasis on blaming the air disasters on the assembly process which was later found to be not true because metal fatigue was the cause."

Even today, some myths and mysteries remain.

The Comet

The de Havilland DH.106 Comet was the world's first commercial jet airliner. Developed and manufactured by de Havilland at its Hatfield Aerodrome in Hertfordshire, United Kingdom, the Comet 1 prototype first flew in 1949. It featured an aerodynamically clean design with four de Havilland Ghost turbojet engines buried in the wing roots, a pressurised cabin, and large square windows. For the era, it offered a relatively quiet, comfortable passenger cabin and was commercially promising at its debut in 1952. The de Havilland Aircraft Company decided in 1952 that their Broughton factory would manufacture the next generation Comet 2s and 3s.

Design work on the Coment was kicked off at a meeting of the March 1943 Brabazon Committee, which was tasked with determining the UK's airliner needs after the conclusion of the Second World War. It was only that March that the Gloster Meteor, the first Allied jet fighter, made its first flight, but it had already become clear that the war was likely to be won. One of its recommendations was for the development and production of a pressurised, transatlantic mailplane that could carry non-stop, one ton of payload at a cruising speed of 400 mph (640 km/h). A development and production contract to de Havilland under the designation Type 106 was awarded in February 1945. The type and design were to be so advanced that De Havilland had to undertake the design and development of both the airframe and the engines. This was because in 1945 no turbojet engine manufacturer in the world was drawing up a design specification for an engine with the thrust and specific fuel consumption, that could power an aircraft at the proposed cruising altitude (40 thousand feet), speed, and transatlantic range as was called for. The high altitude was needed for two reasons: to avoid poor weather and to run the fuel-thirsty early jet engines at an economic efficiency. However the high altitude required the cabin to be pressurised, which would put strains on the hull not previously encountered. There had been pressurised passenger aircraft before, but these were prop-driven and flew a much lower altitude.

As the Comet represented a new category of passenger aircraft, more rigorous testing was a development priority. From 1947 to 1948, de Havilland conducted an extensive research and development phase, including the use of several stress test rigs at Hatfield Aerodrome for small components and large assemblies alike. Sections of pressurised fuselage were subjected to high-altitude flight conditions via a large decompression chamber on-site, and tested to failure. However, tracing fuselage failure points proved difficult with this method, and de Havilland ultimately switched to conducting structural tests with a water tank that could be safely configured to increase pressures gradually. The entire forward fuselage section was tested for metal fatigue by repeatedly pressurising to 2.75 pounds per square inch (19.0 kPa) overpressure and depressurising through more than 16,000 cycles, equivalent to about 40,000 hours of airline service. Finally, the pressure was racked-up until the hull failed, it did so under pressure conditions well above what would be expected in use.

In 1953 the Comet appeared to have achieved success for de Havilland. Popular Mechanics wrote that Britain had a lead of three to five years on the rest of the world in jetliners. As some guides to Chester state, within a year of entering airline service, problems started to emerge, with three Comets lost within twelve months in highly publicised accidents, after suffering catastrophic in-flight break-ups. Two of these were found to be caused by structural failure resulting from metal fatigue in the airframe, a phenomenon known but not fully understood at the time; the other was due to overstressing of the airframe during flight through severe weather. After the third of these crashes, the Comet was withdrawn from service and extensively tested. Design and construction flaws, were ultimately identified. As a result, the Comet was extensively redesigned, with oval windows, structural reinforcements and other changes.

As is often the case, the truth is a little more complicated than that simple version.

The Crashes

Around 50% faster than equivalent piston engine aircraft, scheduled flights from London to Tokyo on Comet took just 36 hours compared to the 86½ hours recorded by aircraft such as the BOAC Argonauts who had previously dominated the route. In its first year, Comets carried over 30,000 passengers and at least 8 Comet flights departed London each week, destined for Johannesburg, Tokyo, Singapore and Columbo. Sadly the history of the Comet 1 is dominated by the two devastating accidents to G-ALYP, which was destroyed off Elba in January 1954 and G-ALYY which disappeared near Naples in April of the same year. Overall, the Comet was involved in 26 hull-loss accidents, including 13 fatal crashes which resulted in 426 fatalities, but three early accidents are the best known, these were BOAC Flight 783 on 2 May 1953, BOAC Flight 781 on 10 January 1954, and South African Airways Flight 201 on 8 April 1954, led to the grounding of the entire Comet fleet.

Contrary to popular belief these were not the first Comet accidents. On 26 October 1952, the Comet suffered its first hull loss when a BOAC flight departing Rome's Ciampino airport failed to become airborne and ran into rough ground at the end of the runway. Two passengers sustained minor injuries, but the aircraft, G-ALYZ, was a write-off. On 3 March 1953, a new Canadian Pacific Airlines Comet 1A, registered CF-CUN and named Empress of Hawaii, failed to become airborne while attempting a night takeoff from Karachi, Pakistan, on a delivery flight to Australia. The aircraft plunged into a dry drainage canal and collided with an embankment, killing all five crew and six passengers on board. The cause of these accidents was later determined to be a loss of lift due to the wing design. On 2 May 1953, BOAC Flight 783, de Havilland Comet G-ALYV, broke up mid-air and crashed after encountering a severe thunderstorm squall, shortly after taking off from Calcutta (now Kolkata), India. All 43 passengers and crew on board were killed. The inquiry concluded that the aircraft had encountered extreme negative G forces during takeoff; severe turbulence generated by adverse weather was determined to have induced down-loading, leading to the loss of the wings. Examination of the cockpit controls ar first suggested that the pilot may have inadvertently over-stressed the aircraft when pulling out of a steep dive by over-manipulation of the fully powered flight controls.

On 10 January 1954, 20 minutes after taking off from Ciampino (Rome), the first production Comet, G-ALYP which had flown the most, broke up in mid-air while operating BOAC Flight 781 and crashed into the Mediterranean off the Italian island of Elba with the loss of all 36 on board. With no witnesses to the disaster and only partial radio transmissions as incomplete evidence, no obvious reason for the crash could be deduced. Media attention centred on potential sabotage, but it was concluded that the likely problem was fire, possibly caused by turbine blades being shed. No apparent fault in the aircraft was found, and the British government decided against opening a further public inquiry into the accident. The prestigious nature of the Comet project, particularly for the British aerospace industry, and the financial impact of the aircraft's grounding on BOAC's operations, both served to pressure the inquiry to end without further investigation. Comet flights resumed on 23 March 1954, with armour added to the engines to protect against flying turbine blades. G-ALYP had first flown on 9th January 1951 and recorded the types first "fare-paying" flight to Johannesburg with BOAC in May of the same year. The aircraft was an instant hit with the passengers including Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother and Princess Margaret who were VIP’s on a special flight in June 1953.

On 8 April 1954, Comet G-ALYY ("Yoke Yoke"), on charter to South African Airways, was on a leg from Rome to Cairo (of a longer route, SA Flight 201 from London to Johannesburg), when it crashed in the Mediterranean in very deep water near Naples with the loss of all 21 passengers and crew on board. The Comet fleet was immediately grounded once again and a large investigation board was formed. The inquiry closed on 24 November 1954, having "found that the basic design of the Comet was sound", and made no observations or recommendations regarding the shape of the windows. De Havilland nonetheless began a refit programme to strengthen the fuselage and wing structure, employing thicker gauge skin and replacing the square windows and panels with rounded versions. One effect of the thicker skin was to reduce the range of the aircraft making it unsuitable for the intended North Atlantic run.

After design modifications were implemented, Comet services resumed in 1958. With the discovery of the structural problems of the early series, all remaining Comet I's were withdrawn from service. Perhaps fortunately, a nuclear bomb carrying design (DHIII) - known as the "Comet Bomber" - which received a negative evaluation from the Royal Aircraft Establishment had also been cancelled back in 1948. De Havilland launched a major effort to build a new version that would be both larger and stronger. Despite this, all outstanding orders for the Comet 2 were cancelled by airline customers. Besides the new 707 and DC-8, the introduction of the Vickers VC10 allowed competing aircraft to assume the high-speed, long-range passenger service role pioneered by the Comet.

The Cause

One part of the investigation examined cabin pressurisation. These tests used water to produce cabin loading and hydraulic rams to generate wing loading. BOAC Comet, Yoke Uncle, was placed inside a water tank with the wings protruding through seals in the walls of the tank. The loads which were applied simulated a three hour flight in ten minutes. This was carried out by the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) at Farnborough and a court of enquiry was established to examine both the crash evidence and the test results. The skin of Yoke Uncle had undergone 3057 flight cycles (1221 actual and 1836 simulated) before a fatigue crack produced a failure. This occurred at a rivet hole near the forward port escape hatch, ripping open the side of the aircraft. One common misconception is that fatigue was an unknown phenomena at the time the Comet was designed. In fact as early as 1837 Wilhelm Albert had published the first article on fatigue and during the 1840s fatigue related railway failures were identified in France and the UK (including the Dee Bridge Disaster). However, what were not well understood were suitable ways to analyse and test designs for their resistance to fatigue.

The image of the Comet in Chester is apparently of one of the two Mark II comets made to a specific order by Short Brothers and Harland Limited in Belfast and taken to Broughton in October/November 1955. This was not a production run but for further special testing after the three crashes of comets a few years earlier. This shipping of wingless hulls by road was apparently not the normal production method for the comet. The actual purpose for which the two special orders were sent to Broughton is not known.

The planes were shipped from Belfast to Preston by sea onboard the Empire Cymric. The Cymric had originally been built as LST 3010 for the Navy in 1944 and served the Dutch Koninklijke Marine in 1945-7. In 1947, she was returned to the Royal Navy and was renamed "Attacker". She was chartered by the Ministry of Transport and converted to a ferry. In 1955, she was sold to the Atlantic Steam Navigation Company and renamed Empire Cymric, operated on the Preston - Belfast route. After shipping to Preston, because of low bridges, the comets had to travel by a long route through Manchester, Stockport and Chester to get to Broughton. The trip took a week in total with the first aircraft arriving at Broughton on 1st November 1955. This dates the well-known photograph of the Comet passing through Chester to the end of October or perhaps the first day of November.

The Empire Cymric has a curious history all of her own, some of which seems a little "cloak and dagger". She is shown in war footage as she accompanies Dutch forces as they make an amphibious landing on the island of Bali in the Netherlands East Indies (Indonesia). She was later requisitioned by the Royal Navy for use during the Suez Crisis, when she was escorted from Malta to Port Said, Egypt by submatine depot ship HMS Forth, which escorted her back to Malta after the crisis was over. She served until 1963, arriving on 1 October at Faslane, Dunbartonshire for scrapping.

While one result of the crashes was the adoption of round windows, the problems which led to the actual accidents were at the time believed to be associated with a small aperture in the cabin roof which housed a direction finder (ADF) beneath a fibre-glass "window" panel. This had rounded corners but had been "punch riveted" rather than glued as in the aircraft's original design specifications. Punch riveting had been used for years on aircraft designed to fly at a lower altitude, i.e. for hulls subjected to less pressure differences. It was believed that, had this short-cut not been taken, the accidents might well not have happened. Even drilling the holes might have saved the planes, as the uneven pressure of the punch process led to the "starter" cracks for the fatigue fragmentation. The accident investigation also found that square main windows had the potential to cause problems, but everyone believed that the cracks which caused the actual crashes started with a round rivet hole.

In June 1956 some more wreckage from G-ALYP was accidentally trawled up from an area about 15 miles south of where the original wreckage had been found. This wreckage was from the starboard side of the cabin just above the three front windows, and what it revealed muddies the waters considerably. Subsequent examination at Farnborough suggested that the primary failure was probably near to this area rather than at the rear automatic direction finding window on the roof of the cabin as had been previously thought. However, these findings were kept secret until the details were published in 2015, leading to a whole generation of engineers having been taught that the problem was the rivet holes around the ADF port. There are other theories as to why whatever flaw in the design was actually present was missed, one being that the pressure testing that was carried out on prototypes performed a "cold working" on the pressure shell which removed potential defects so that a final high-pressure failure test allowed a much higher pressure to be reached than would have caused failure with a new shell, even if the problem was the rivet holes. Like many accidents, the answer is probably a combination of factors: the type of testing, plus the use of rivets, plus the way the holes were punched.

The Hawker Siddeley Nimrod was a maritime patrol aircraft based on extensive modification of the de Havilland Comet. In addition to the three Maritime Reconnaissance variants, two further Nimrod types were developed. The RAF operated a small number of the Nimrod R1, an electronic intelligence gathering (ELINT) variant. A dedicated airborne early warning platform, the Nimrod AEW3, was in development from late 1970s to the mid-1980s; however, considerable problems were encountered in development and thus the project was cancelled in 1986 in favour of an off-the-shelf solution in the Boeing E-3 Sentry. All Nimrod variants had been retired by mid-2011. The last civil Comet to fly was Comet 4C, G-BDIX on her journey to East Fortune (Scotland) in September 1981, where the aircraft is still on display.

Cloak and Dagger

The failures of the Comet touched on matters that went far beyond simple commercial issues. While the initial Comet engines were the "centrifugal-flow" de Haviland Ghost's, the next generation of the Comet was to use the Rolls-Royce Avon engine. This was an "axial-flow" engine, a significantly more efficient arrangement. Airlines from around the world lined up to purchase the Avon-powered craft. British policymakers were hopeful that Comet sales would help give the nation the economic boost it needed in the years following World War II. Duncan Sandys, the United Kingdom’s supply minister, wrote to Prime Minister Winston Churchill:

- "On whether we grasp this opportunity [for extensive Comet sales] and so establish firmly an industry of the utmost strategic and economic importance, our future as a great nation may to no small extent depend."

The United States objected to the sales, citing concerns that lax airline security in foreign nations offered innumerable opportunities for Communist agents to steal the technological secrets of the Avon. And with Avon-like engines affixed to their wings, Soviet airplanes might gain the range and the payload capacity to launch, for the first time, atomic strikes against the United States. The Comet, had, after all, also been proposed as an atomic bomber, and the Soviets had been quick to acquire the technology of the "Nene" engine and copy it (as the Klimov VK-1) for the Mig-15. The speed with which the Soviets had copied the U.S. B-29s and the British Nenes naturally made the U.S. military worry: If Comets were now to be sold to other nations, the aircraft’s Avon engines might eventually end up in Soviet hands too, and be duplicated. The UK were prodded into adopting certain safeguards, including that no airplane powered by, or carrying, a Comet engine could ever fly to, or over, Communist-held territory, all maintenance work must be carried out by security screened British technicians, on British territory, and all spare parts muct be carried on British ships and subject to stringent security. In 1954, London decided to proceed with its Comet export plans. The U.S. state department prepared the Congress for another round of startling revelations: Britain was about to sell airplanes that could eventually aid the enemy. U.S. officials were hard at work putting the finishing touches on their damning brief when, in an instant, news of the Comet crashes arrived and the entire situation changed.

Given the political sensitivity over the Comet's technology it is not unsurprising that stories of sabotage theories appeared in the press. These could equally have also been a reaction to the thought that the design could have a fatal flaw. This was not the only ongoing dispute over technology that was ongoing at the time with the Americans, as the British were rushing to develop their own atomic weapons and maintain their status as a major world power. It was an argument that went back to the Tizard Mission of 1940, when the British introduced the US among other things to the newly invented resonant-cavity magnetron and other British radar developments, the Whittle jet engine, and the British Tube Alloys (nuclear weapons) project. It would however be perhaps a step too far (without further evidence) to assume that the involvement of the "cloak and dagger" ship "Empire Cymric" in bringing the Comets to Chester is anything other than a co-incidence.

Summary

While the Comet 4 operated the first trans-Atlantic jet service on 4 October 1958, de Havilland’s advantage had been lost as the first of 855 Boeing 707's entered service only nine days after the Comet 4 and made its first trans-Atlantic scheduled flight on 26 October 1958. Even with modifications only 78 Comets of any type (of the 114 built, including prototypes) would ever be delivered to airlines, whereas its new competitors would sell hundreds. In all, eight hundred and fifty-five 707s would roll off Boeing’s assembly lines. The myth that it was "square windows" which caused the crashes has become established, although it appears to be a simplification and distortion of the truth. Another common myth is that the majority of the Comet deaths were due to the window problem, whereas only 57 of the over 426 fatalities associated with the Comet occurred in the "window" crashes.

The Comet II being shipped through Chester still presents some mystery. It has the original square window design and appears to be one of only two aircraft shipped from Belfast to Broughton as an exception and only apparently for experimental purposes. What eventually happened to them is not clear. All but four Comet II's were converted for military use. Whether the aircraft shown in the photo's became one of these is unknown. Any story that the Chester Ring-Road was built because of the problems of shipping Comets through Chester is an urban myth, and most people seeing the photograph do not realise that the only reason the aircraft was being transported through Chester was because of a series of air-disasters and many deaths. Other myths associated with the photo include that the ladder is being used to hold the overhead tram cables out of the way, although the trams were discontinued in 1930 and the electric overheads taken down shortly afterwards.

Returning to the quote at the head of this article, of the seven Comet accidents in the period 1952-54 (resulting in 110 deaths) the causes given were "pilot error", "runway excursion", and "fatigue failure". None of the accident reports mention a missing washer.

Trivia

There is a pub called "The Comet" on the Barnet bypass at Hatfield. One might think it is named after the jet aircraft, but the pub opened in late 1936. The de Havilland aircraft factory was near the pub and the prop-driven Comet DH-88 was then the firm’s most famous plane, having been flown by Flight Lieutenant Charles William Anderson Scott and Tom Campbell Black in their winning run during the 1934 London to Melbourne Air Race. Their aircraft was Comet G-ACSS "Grosvenor House|" this was in turn named after the Grosvenor House Hotel, a luxury hotel that opened in 1929 in the Mayfair area of London, England. Across from Hyde Park, the hotel is built on the former site of the 19th century aristocratic Grosvenor House residence built for Robert Grosvenor, 1st Marquess of Westminster.

Sources and Links

Related Pages

- Historiography: how historical myths arise;

Books

There are additional photographs (including of the Empire Cymric/LST3010) in Paul Hurley's history of Chester in the 1950's.

Online

- website dedicated to DH 106 Comet;

- BaE page on the Comet;

- The "Comet Bomber";

- Accident Reports;

- de Havilland DH-106 Comet: statistics at Aviation Safety Network;

- Misconceptions about the accidents: with videos;

- "Seconds from disaster": documentary;

- Comet’s Tale: from the Smithsonian magazine;

- More on the curious history of the LST 3010;